It is especially appropriate given tonight’s topic that I acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which this fine university stands: the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people. I respectfully note that long before James Cook University (JCU) was built here, and indeed for millennia before European settlement, the ancestors of the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people lived and prospered on this land. No doubt they held regular meetings with their Elders to discuss matters of community interest and concern, in essence not so very different to tonight.

It is especially appropriate given tonight’s topic that I acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which this fine university stands: the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people. I respectfully note that long before James Cook University (JCU) was built here, and indeed for millennia before European settlement, the ancestors of the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people lived and prospered on this land. No doubt they held regular meetings with their Elders to discuss matters of community interest and concern, in essence not so very different to tonight.

I also want to acknowledge the trail-blazing non-Indigenous elder of the Queensland community, Marilyn Mayo, in whose honour this annual lecture is held. Townsville does trail-blazing women well. It has claim to Queensland’s first woman lawyer, Agnes McWhinney, who was admitted as a solicitor in 1915. As one of the first women law lecturers in Australia, Marilyn Mayo was instrumental in establishing the JCU’s Faculty of Law and was its first Head of Department. I regret that I did not know her. We’d have got along. As a woman lawyer who followed the trail she blazed, I thank her and honour her memory.

Let me begin with the notorious case of KU & ors. Three young adult men and four youths pleaded guilty to the penile rape of a 10 year old girl in Aurukun. The adults were initially sentenced to six months imprisonment suspended immediately for 12 months, and the youths to 12 months probation without conviction. After the expiry of the appeal period, Tony Koch, writing for The Australian, and then the wider media, criticised the sentences. There was a public outcry throughout Australia and internationally. In February 2008, the Court of Appeal granted the Attorney-General an extension of time to appeal.2 Together with the Chief Justice and Justice Keane, I heard that appeal in June 2008. I found it distressing, despite my experience over 33 years as a criminal law barrister and a judge.

Let me begin with the notorious case of KU & ors. Three young adult men and four youths pleaded guilty to the penile rape of a 10 year old girl in Aurukun. The adults were initially sentenced to six months imprisonment suspended immediately for 12 months, and the youths to 12 months probation without conviction. After the expiry of the appeal period, Tony Koch, writing for The Australian, and then the wider media, criticised the sentences. There was a public outcry throughout Australia and internationally. In February 2008, the Court of Appeal granted the Attorney-General an extension of time to appeal.2 Together with the Chief Justice and Justice Keane, I heard that appeal in June 2008. I found it distressing, despite my experience over 33 years as a criminal law barrister and a judge.

The offence of rape includes carnal knowledge of a person (in essence, sexual intercourse) without the person’s consent.3 Rape often, but by no means always, involves physical violence. This case involved little physical violence. A child under 12 is incapable at law of giving consent.4 The victim’s tender age turned the offenders’ unlawful acts of sex into rape.

There was not much information about the offenders before the Court and we ordered pre-sentence reports. These reports included:

“Aboriginal youths [have] an excessively negative outlook on life with low self-esteem being characteristic. Cultural dislocation and dispossession appear to have disrupted and even removed traditional rites of passage into adulthood and a cultural vacuum is the result. As a result of the crisis of identity in not knowing traditional culture, young people tend to find a sense of identity in a sub-culture where offending behaviour, drug taking and work avoidance become new rites of passage.”5

The reports painted gloomy canvases of the dysfunctional lives of both the pre-teen victim and the offenders and their families. But there were occasional glimpses of light. Despite the extreme adversity of Aurukun life, some parents, but more often grandparents or even great-grandparents, were able to retain cohesive family units. Some community members were positive role models for young people and repositories of Indigenous culture and language. Wik-Mangan language was spoken extensively in Aurukun.

The original sentences were too lenient. The Attorney-General’s appeal was allowed. But there were no winners. The adults’ sentences were increased to six years imprisonment with parole eligibility after two years. The youths’ sentences were also increased. Convictions were recorded and new sentences were imposed: from three years probation with participation in rehabilitative programs to two years juvenile detention with release after 12 months.

If you want more details about the case, go to the court website6 and read our reasons. In fact, in any case where media reports suggest Court of Appeal decisions appear outrageous or peculiar, I urge you to do this. And encourage your friends and relatives to do the same. I am confident that, if you read the judges’ reasons for sentencing in full, rather than just the media report of them, decisions will not seem outrageous or peculiar.

During my deliberations on this case, it became clear to me that though the reports revealed gravely flawed aspects of the Aurukun community, like other communities, it was striving to “grow” its children. The reports exposed some of humanity’s basest traits, but also some of its best: the courage, determination and persistence of those exceptional Aurukun community members who, against all odds, valued their language and culture and were positive role models for their young people.

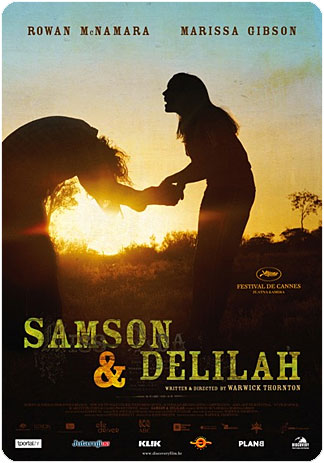

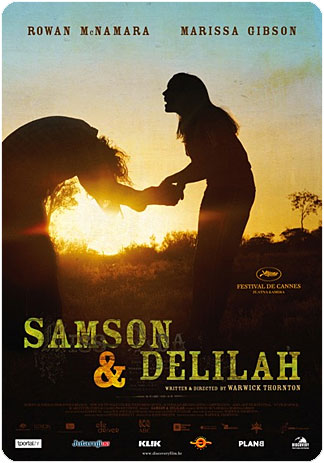

And now, from fact to fiction … the superbly crafted, confronting Warwick Thornton film Samson and Delilah. It won accolades in Australia and internationally7 including the 2009 Camera d’Or at the iconic Cannes Film Festival. It scooped the prizes at the 2009 Australian Film Institute Awards.8

There were many powerful moments: Delilah’s unfair beating by the old Indigenous women; her chilling rape in Alice Springs; and the sickening thud as Delilah, off her tree from petrol-sniffing, was struck by a car. But I especially remember when the talented but penniless fringe-dwelling Indigenous artist, Delilah, entered a coffee shop to sell a painting. The discomfort and embarrassment of the white, prosperous, middle class non-Indigenous clientele was palpable as they tried to ignore the unignorable Delilah until the proprietor removed her from the coffee shop and their lives. Why was I so affected by this scene which did not have the physical violence of the other memorable vignettes? I was affected because I saw myself in those white, prosperous middle class Australian coffee drinkers. I was affected because I empathised with Delilah and knew that, but for an accident of birth, I may have been Delilah. I was affected because I knew that film-lovers all over the world would ask how white, prosperous, middle class Australian coffee drinkers like me could allow this to happen…

But does one notorious court case and a powerful film show the real picture of Indigenous Australia? Of course not. Let’s look at the hard data.

And now, from fact to fiction … the superbly crafted, confronting Warwick Thornton film Samson and Delilah. It won accolades in Australia and internationally7 including the 2009 Camera d’Or at the iconic Cannes Film Festival. It scooped the prizes at the 2009 Australian Film Institute Awards.8

There were many powerful moments: Delilah’s unfair beating by the old Indigenous women; her chilling rape in Alice Springs; and the sickening thud as Delilah, off her tree from petrol-sniffing, was struck by a car. But I especially remember when the talented but penniless fringe-dwelling Indigenous artist, Delilah, entered a coffee shop to sell a painting. The discomfort and embarrassment of the white, prosperous, middle class non-Indigenous clientele was palpable as they tried to ignore the unignorable Delilah until the proprietor removed her from the coffee shop and their lives. Why was I so affected by this scene which did not have the physical violence of the other memorable vignettes? I was affected because I saw myself in those white, prosperous middle class Australian coffee drinkers. I was affected because I empathised with Delilah and knew that, but for an accident of birth, I may have been Delilah. I was affected because I knew that film-lovers all over the world would ask how white, prosperous, middle class Australian coffee drinkers like me could allow this to happen…

But does one notorious court case and a powerful film show the real picture of Indigenous Australia? Of course not. Let’s look at the hard data.

The 2006 census revealed that Indigenous Australians comprise 2.3 per cent of the total population.9 Ninety per cent of those are Aboriginal, 6 per cent Torres Strait Islander and 4 per cent identified as both. Queensland’s Indigenous population is comparatively large.10 Twenty eight per cent of the total Australian Indigenous population lives in Queensland. They comprise 3.5 per cent of Queensland’s total population.11

Almost one-third of Indigenous people reside in major cities, 21 per cent in inner regional areas, 22 per cent in outer regional areas, 10 per cent in remote areas, and 16 per cent in very remote areas.12 In contrast, 69 per cent of the non-Indigenous population live in major cities, with less than 2 per cent in remote and very remote areas.13

Fifty-six per cent of Indigenous respondents living in remote areas spoke an Indigenous language. Indigenous languages are more likely to be spoken in central and northern Australia than in the south.14 Most Indigenous people identified with a clan, tribal or language group.15 This data suggests that culture and language remain significant to Indigenous Australians.

The health of Indigenous Australians appears generally poorer than that of non-Indigenous Australians. One measure of health is life expectancy. Indigenous life expectancy in 2003 was 17 years less than that of the general Australian population.16 The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) notes that 30 years ago, life expectation for Indigenous peoples in Canada, New Zealand and the United States of America, though well below that of the general non-Indigenous populations of those countries, was comparable to that of Indigenous peoples in Australia.17 Concerningly, the data suggests that Indigenous people in Australia now have life expectancies more than 10 per cent less than Indigenous peoples in those countries.18 The United Nations recently noted that the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous life expectancy in Australia is higher than that of many poorer countries such as Panama, Mexico and Guatemala.19 Indigenous infant mortality between 2001 and 2005 was also high: about 6 per cent of total Indigenous deaths, whereas infant deaths in the general population were less than 1 per cent of total deaths.20

Petrol-sniffing featured in the fictional Samson and Delilah. The HREOC encouragingly reports:

The 2006 census revealed that Indigenous Australians comprise 2.3 per cent of the total population.9 Ninety per cent of those are Aboriginal, 6 per cent Torres Strait Islander and 4 per cent identified as both. Queensland’s Indigenous population is comparatively large.10 Twenty eight per cent of the total Australian Indigenous population lives in Queensland. They comprise 3.5 per cent of Queensland’s total population.11

Almost one-third of Indigenous people reside in major cities, 21 per cent in inner regional areas, 22 per cent in outer regional areas, 10 per cent in remote areas, and 16 per cent in very remote areas.12 In contrast, 69 per cent of the non-Indigenous population live in major cities, with less than 2 per cent in remote and very remote areas.13

Fifty-six per cent of Indigenous respondents living in remote areas spoke an Indigenous language. Indigenous languages are more likely to be spoken in central and northern Australia than in the south.14 Most Indigenous people identified with a clan, tribal or language group.15 This data suggests that culture and language remain significant to Indigenous Australians.

The health of Indigenous Australians appears generally poorer than that of non-Indigenous Australians. One measure of health is life expectancy. Indigenous life expectancy in 2003 was 17 years less than that of the general Australian population.16 The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) notes that 30 years ago, life expectation for Indigenous peoples in Canada, New Zealand and the United States of America, though well below that of the general non-Indigenous populations of those countries, was comparable to that of Indigenous peoples in Australia.17 Concerningly, the data suggests that Indigenous people in Australia now have life expectancies more than 10 per cent less than Indigenous peoples in those countries.18 The United Nations recently noted that the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous life expectancy in Australia is higher than that of many poorer countries such as Panama, Mexico and Guatemala.19 Indigenous infant mortality between 2001 and 2005 was also high: about 6 per cent of total Indigenous deaths, whereas infant deaths in the general population were less than 1 per cent of total deaths.20

Petrol-sniffing featured in the fictional Samson and Delilah. The HREOC encouragingly reports:

“… it appears that over 2006 to 2008 the incidence of petrol sniffing in Central Australia has reduced significantly coincident with the rollout of Opal fuel across Central Australia.

… there appears to have been a drop from approximately 600 to 85 sniffers in Central Australia with a drop from 178 to 80 sniffers on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankuntjatjara lands.”21

The economic data is not cheering. Income levels for Indigenous Australians generally decline with geographic remoteness. In 2006, the average equivalised incomes for Indigenous Australians was 69 per cent of the corresponding income for non-Indigenous Australians, but this declined to about 40 per cent in remote areas.22 The median weekly gross individual income for Indigenous Australians ($278) was but 59 per cent of the median weekly gross individual income for non-Indigenous Australians ($473).23 In 2001, 46 per cent of all Indigenous Australians aged 15 to 64 years were not in the labour force compared to 27 per cent of the non-Indigenous population. By 2006, these figures improved, dropping to 43 per cent and 24 per cent, but without any closing of the gap.24 Even these figures do not paint the whole economic picture. Indigenous Australians are twice as likely to work part-time and are more likely to work in low skilled occupations without tertiary qualifications. 25

Encouragingly, educational attainment among Indigenous Australians continues to improve. While Indigenous retention rates at school remain considerably lower than for non-Indigenous students, the disparity is slowly lessening. Rates of year 12 completion improved in Queensland from 26 to 30 per cent between 2001 and 2006.26 But in 2006, Indigenous Australians were only half as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to complete year 12, the same as in 2001.27

Higher education is associated with improvements in long term health. Indigenous people who completed year 12 were about half as likely to suffer diabetes or cardiovascular disease as those who had left school at year 9 or below. They were also less likely to report eye or sight problems, osteoporosis and kidney disease.28

Between 2001 and 2006, the proportion of Indigenous home owner householders increased from 31 to 34 per cent. This compares to the 69 per cent of other Australian home owner households.29 Fourteen per cent of Indigenous households (predominantly rented) were overcrowded.30 In 2006, Queensland had the largest number in Australia of overcrowded Indigenous households (6,200).31

Perhaps the bleakest data concerns the criminal justice system. Almost 20 years ago, the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody reported that Aboriginal people made up 14 per cent of the total prison population and were 15 times more likely to be in prison than non-Aboriginal Australians.32 Despite the implementation of many of the recommendations of that ground-breaking report, Indigenous prisoner numbers have continued to increase. As at 30 June 2008, Indigenous prisoners represented 24 per cent of prisoners.33 The Indigenous female imprisonment rate increased by a shocking 34 per cent between 2002 and 2006 while the imprisonment rate for Indigenous men increased by 22 per cent.34 Indigenous Australian women are 23 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Indigenous women. Indigenous Australian men are 16 times more likely to imprisoned than non-Indigenous men.35

The rate of Indigenous children placed on care and protection orders was around seven times the rate for other Australian children.36 But the HREOC notes that:

“… non-Indigenous children subject to child protection substantiations were more likely than Indigenous children to have substantiations where the main type of abuse was sexual. In New South Wales, 17 per cent of non-Indigenous Australian children subject to child protection orders had substantiations of sexual abuse compared with nine per cent of Indigenous children. In the Northern Territory, these figures were 4.2 per cent compared to 9.3 per cent.”37

The HREOC observes that these figures do “not appear to support the allegations of endemic child abuse in NT remote communities”.38

The HREOC emphasises the economic benefit to all Australians in improving the quality of life of Indigenous Australians. It will result in increased real GDP through more Indigenous Australians in higher skilled and better paid jobs, with less economic burden on the health and social security system.39 My lifetime experience suggests that it would also result in a drop in Indigenous representation in the notroriously costly criminal justice system.

Let us not forget that, for generations many good-hearted Australians have been striving to improve Indigenous quality of life. Despite their best intentions, efforts and very considerable government funding, progress has been glacial. There have been monumental mistakes. Australia’s past child removal practices are perhaps the starkest. Its effects are still with us. The HREOC reports that of a recent survey of Western Australian Aboriginal people, 35.3 per cent lived in households where a carer or a carer’s parent was reported to have been forcibly separated from their natural family.40 Those carers were between one and a half to two times more likely than others to suffer from dysfunctional problems including arrest on criminal charges, over-use of alcohol, betting or gambling problems and contact with mental health services.41 Further, they had poorer parenting skills:42 their children were 2.34 times more likely to be at high risk of clinically significant emotional behavioural difficulties than those whose carers were not forcibly separated from family.43

The hard data supports the conclusion that Australia must do better in terms of our Indigenous citizens.

Shortly after watching Samson and Delilah, I was moved by a quite different film experience: Joanna Lumley’s charming documentary Northern Lights. The lovely Joanna took me on a journey through Norway by train, boat, husky sled and snow mobile, to track down the elusive northern lights about which she read and dreamt as a small child in tropical Malayasia. She passed through Norway’s scenic fjords into the tundra of Lappland where she spoke to Sami herdsmen searching for their reindeer. She shared a traditional song with a Sami community elder. Joanna remarked that today around 80,000 Sami people live across Arctic Scandanavia, adding:

“Until recently [the Sami] were commonly known as Lapps, inhabitants of a region called Lappland, reviled as little better than savages, they suffered for centuries. But Sami identity and the Sami language are now enjoying a renaissance. There were no roads here until the 1960s but now almost everyone has mobiles and broadband internet and they enjoy one of the highest standards of living in the world.”

The documentary ended serendipitously with Joanna realising her childhood dream: she saw the elusive solar light show. But it was her words about the Sami that resonated with me. They took me back to the Aurukun rape case and Samson and Delilah. How was it that in 40 years the Sami had progressed from being “reviled as little better than savages” to enjoying “one of the highest standards of living in the world”? Australia is not Norway and the Sami are not Indigenous Australians. But could Australians learn from the Sami success as to how we might do better for our Indigenous citizens?

This is where my long-suffering associate, Katie Allan, came in!

The Sami are an Indigenous people, traditionally living in the far northern areas of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. For 2,000 years, the Sami were regarded as a remote and exotic curiosity, “the most remote primitive nomads on European’s northern fringe”.44 Norway’s Sami are the largest ethnic minority in Norway and the largest Sami group in any single country.45 I will confine the present discussion to the Norwegian-Sami experience.

In the early part of the 20th century, the Norwegian policy on its Sami people was one of assimilation.46 This correlates with the Indigenous Australian policy at that time and with Australia’s past policy of Indigenous child removals.

In 1979, the Norwegian government began to dam a water course as part of a hydro-electric scheme. The Sami considered the scheme a threat to reindeer grazing areas and an infringement of their traditional rights to land and water. Their cause gained national and international attention and it became a focus of civil disobedience for Samis and sympathetic Norwegian environmental groups. The Sami brought an action in Norway’s courts to stop the dam. The Alta case47 became a seminal decision about Sami Aboriginal fundamental human rights and international law. The Sami lost their claim but Norway’s highest court recognised them as a distinct ethnic minority with special rights protected under international law.48

There are analogies between the Alta case and Australia’s Mabo No 2.49 In Mabo, the Australian High Court unequivocally recognised that the doctrine of terra nullius was a legal myth and that Australia was already inhabited when colonised by the British.50 Like the ground-breaking Alta case in Norway, the Mabo decision became a major turning point in Australian history. Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians alike saw it as a keystone in the stairway to reconciliation.

But unlike Australia after Mabo, Norway after Alta took an international leadership role in its relationship with its Indigenous people.51

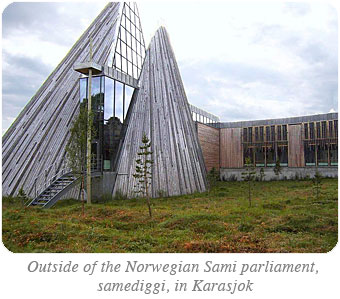

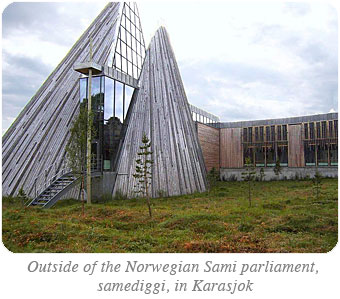

In 1989, Norway established a “Sami parliament” to deal with discrete Sami matters. Importantly, this parliament is not concerned with the establishment of an independent Sami state but only with the protection of the traditional Sami lands against exploitation, and the clear recognition of traditional Sami hunting, fishing and reindeer herding rights.52

In 1989, Norway established a “Sami parliament” to deal with discrete Sami matters. Importantly, this parliament is not concerned with the establishment of an independent Sami state but only with the protection of the traditional Sami lands against exploitation, and the clear recognition of traditional Sami hunting, fishing and reindeer herding rights.52

In 1992, Norway was the first country to ratify the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages,53 making express reference to the Sami language.

The research of my associate, Katie Allan, supports Joanna Lumley’s statements about the dramatic improvement in recent decades in the Sami quality of life. In 1990, 32.5 per cent of the Sami population stated their highest level of education was secondary school.54 By 2010, this figure had risen by 19 per cent.55 Even more impressively, between 1990 and 2008, the number of Sami completing tertiary education rose by 88 per cent.56 Seventy per cent of Sami speak Sami.57 The Sami have realised the importance of language in preserving their culture. Non-Sami politicians and government agencies in Scandanavia also recognise and respect this.58 There is now little difference in Norway between the life expectancy of Sami (76.6 years) and non-Sami (78.3 years).59 There is little difference between perceived health needs and the use of health services as reported by Sami and non-Sami youth in Norway.60 Compared to their non-Sami Norwegian peers, Norwegian Sami adolescents have just as good mental health and actually demonstrate less substance and drug abuse.61

These dramatic improvements in Sami quality of life correlate with increased Sami pride in language and culture; increased Sami economic prosperity; Sami self-determination on discrete Sami issues; and the respect and value given to individual Sami and Sami language and culture within the broader Norwegian community.62

I return to the question in the title of tonight’s lecture: how might we do better in improving the quality of life of Australia’s Indigenous people? Is the answer, at least in part, in developing a Norwegian-like mindset?

Current Australian Indigenous government policy is informed by the International Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People,63 a milestone development in international law. This Declaration does not have the force of law in that it is aspirational. But it encourages nations to enact legislation appropriate to its aims. The Declaration was overwhelmingly adopted by the UN General Assembly on 7 September 2007 with 143 votes in favour and only four countries against. One was Australia. But on 3 April 2009, Australia belatedly acknowledged the importance of this Declaration by adopting it. The Declaration appears to draw on the Sami success story. It recognises Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination and autonomy in internal and local affairs and in financing autonomous functions.64 This right to self-determination does not permit action which threatens the territorial integrity of a state.65 It concerns procedure and process and requires Indigenous consultation on decisions that effect Indigenous citizens’ lives as individuals and communally.

Mr Mick Gooda, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Commissioner, recently argued the case for the practical power of human rights, stating:

“Actions without a solid foundation based on rights will always fall in the longer term because actions and human rights are … inextricably linked.”66

He points out that poor Indigenous Australians’ health outcomes are a human rights issue that has led to policy change and practical action. He emphasises the inter-relatedness and indivisibility of human rights and that governments should develop truly holistic and integrated approaches to addressing disadvantage in Indigenous communities. Referring to the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, Mr Gooda expresses the hope “that we can finally embrace a true and genuine ‘mateship’ between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the broader Australian community”.67

In September 2009, Australia’s National Human Rights Consultation Report recommended that:

“In partnership with Indigenous communities, the federal government develop and implement a framework for self-determination outlining consultation protocols, roles and responsibilities (so that the communities have meaningful control over their affairs) and strategies for increasing Indigenous Australians’ participation in the institutions of democratic government.”68

Current Australian Indigenous policy has seen the formation of a new Indigenous council, the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples. It may not be equivalent to the “Sami parliament”, but it might result in Australia’s Indigenous people gaining some autonomy and control over Indigenous matters. All Australians should watch its progress with interest.

The Sami success has been closely linked to Sami culture, language, high education levels and economic prosperity. Unlike the Sami, Australia’s Indigenous peoples have many languages and tribal or clan groups. But the data to which I have referred indicates that, like the Sami, most indigenous Australians identify with a clan, tribal or language group, and that Indigenous language is spoken by most Indigenous Australians in remote areas. North Queensland Indigenous leader, lawyer and activist, Noel Pearson, has often emphasised the importance of Indigenous language to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.69 He advocates for a “modern literate prosperous version” of Indigenous culture;70 insists that Indigenous rights be coupled with Indigenous responsibility; and refuses to excuse damaging Indigenous behaviour which weakens Indigenous society.71 He is a tireless advocate for increased educational opportunities for Indigenous Australian students.72

The Queensland government with bipartisan support this week announced that schools will provide Indigenous students in grade 12 with a “service guarantee” of an education that is capable of leading to a job or a university place.73

I have a young Indigenous friend, Tammy Williams. Like Marilyn Mayo, Ms Williams is something of a trail-blazer. She is a lawyer, a sessional member of the Queensland Civil & Administrative Tribunal, and a founding director of Indigenous Enterprise Partnerships, a not-for-profit organisation which channels corporate and philanthropic resources into Indigenous development. She was also a member of Australia’s National Human Rights consultation group. And she and her husband have a pre-school child! Ms Williams advocates for a whole of government and cross-government approach in Indigenous policy matters, but only after reaching agreement with key Indigenous leaders about the appropriate vision and strategic approach. Before introducing new policies, government should invest resources in stabilising the Indigenous community by supporting and strengthening the functional existing key infrastructure, leaders, organisations and projects with a proven track record.74 Highly functional organisations and projects must be given five year funding cycles.75

In my own patch, I recognise the good sense of these observations. I have repeatedly seen the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service struggle because of uncertain funding. Strategic planning and long term functionality is impossible for any organisation without a guaranteed funding cycle.

Ms Williams emphasises the positive aspects of Indigenous culture: kinship, family bonds and respect; traditional roles, responsibilities and historical connections, including to the land; and spirituality. But she recognises that a destructive sub-culture has developed through decades of dispossession and inappropriate government policy with negative aspects including alcohol, drugs, gambling, and ostracising community members who are successful in the non-Indigenous community in fields outside sport and the arts.76 I note that destructive subculture was central to both the Aurukun rape case and Samson and Delilah. Ms Williams argues that the negative aspects of the destructive subculture can be side-lined by strong support for the positive aspects. Indigenous and non-indigenous respect and support for community leaders and organisations is needed to build a constructive and positive sub-culture. She points out that in 2003 only one of the 18 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Commission (ATSIC) commissioners was a woman.77 Indigenous women struggle to have a political leadership voice and financial control in their community. Ms Williams argues that this must change. JCU trail-blazer, Marilyn Mayo, would, I

think, agree!

Highly respected Indigenous academic, Marcia Langton,78 echoes this call for Indigenous women to participate more in public life. Ms Langton recently called for an end to “big bunga politics”, what she calls “the real politik of power in our world — power that is all too often used against women and children, power that takes many forms and has too frequently been used for personalised aggrandisement. The big bunga way — a scatological term used to refer to the ‘big man’ syndrome — works to the advantage of a few and has become normalised, and even glorified, in some circles. Meanwhile, assault, rape and an astonishing variety of other mental and physical forms of abuse have become the norm in far too many communities and families.”79 She urges non-Aboriginal people to “be better informed and engage in a rational debate with [Indigenous people], and overcome their preference for the ‘big bunga’ Aboriginal political representatives and the guilt-infused romance with the exotic. … Many of the people working in the Aboriginal industry are not seeking alliances with ordinary, hard working, effective people, but the black woman in the plain dress with the soft voice will usually work far harder and be more effective. It is time to listen to her, and her quietly-spoken sisters and brothers, rather than the noisy bullies.”80 I think Marilyn Mayo would have agreed with that, too.

Australia’s international obligations under the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People and the current views of Australian Indigenous intellectuals and leaders seem to support Australia developing an Indigenous policy analogous to that of Norway’s to its Sami. But although we all vote and have a voice, most of us are not legislators, policy makers or activists. Returning once more to the topic of tonight’s lecture, how might we, each of us, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, do better?

Sound government policy is clearly critical to success. But we can all do better: through our universities and workplaces, our community and professional organisations and individually.

Many organisations and thousands of individuals are sponsoring the education of talented Indigenous students. Let me give some examples. The Yalari initiative,81 founded by Indigenous educator Waverley Stanley and his wife Llew Mullins, allows corporate partners, individuals and community organisations to financially support or mentor indigenous students attending some of Australia’s leading boarding schools. Also, the Queensland Law Society sponsors a scholarship for Indigenous law students. The Brisbane law firm, McCullough Robertson, provides a scholarship through QUT to support Indigenous law students. The Australian Medical Association awards an Indigenous peoples’ medical scholarship each year to increase the number of Indigenous Australian doctors. JCU, to its credit, has many indigenous bursaries as well as mentor programs.82

Together with respected Brisbane Indigenous Elder, Uncle Bob Anderson, I am a member of the Council of Griffith University which, no doubt like JCU and other leading Australian universities, strives to encourage Indigenous students. At Griffith, the rate of Indigenous student participation, retention and success is above the national average. In fact, the success rates of Indigenous students at Griffith now surpass those of non-Indigenous students.83

But perhaps it is at an individual level where we can effect the greatest change and where we might all do better. I suggest that when we non-Indigenous Australians are impressed with what Indigenous co-students, co-workers or acquaintances do, or how they do it, we tell them. And vice-versa! Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians need to take time to get to know each other better. If appropriate, we can give each other support, and, if asked, advice. We should offer to be a mentor or to be mentored. In the spirit of reconciliation, non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australians should share good and generous hearts and wise and open minds. Chances are our Indigenous and non-Indigenous lives will be enriched by the resulting human symbiosis. Non-Indigenous Australians will learn more of Indigenous culture and language.84 After all, Indigenousness is the unique aspect of Australia in an increasingly globalised, standardised and homogenised world. Our new Indigenous mates will be empowered to make their full contribution to the mainstream Australian community as they gain confidence through the acceptance of their new non-Indigenous mates. We should encourage our Indigenous and non-Indigenous friends and relations to join in this human symbiosis.

Indigenous Australians need to know that non-Indigenous Australians value them individually and collectively, and their culture and language. They need to have autonomy and control over Indigenous policy issues. Indigenous Australians may sometimes need to subjugate short-term clan interests in the long term interests of the broader Indigenous community.

If we mainstream non-Indigenous Australians can open these tributaries of mateship to capable Indigenous Australians like Marcia Langton’s “black woman in the plain dress with the soft voice”, the mainstream will be broadened. If the courteous brown skinned law student with the well-trimmed beard, the sparkling eyes and the ready smile can open these tributaries of mateship to non-Indigenous Australians, the mainstream will be enriched. If enough of us, Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians alike, take this approach, it is likely that, as has happened in Norway over the past 40 years, there will be remarkable improvements in the economic, education and health outcomes of Australia’s Indigenous citizens. And the quality of life of Australia’s non-Indigenous citizens will also be symbiotically enriched.

The Honourable Justice Margaret McMurdo AC

Footnotes

1. R v KU & ors; ex parte A-G (Qld) [2008] QCA 154.

â President, Court of Appeal, Supreme Court of Queensland. The author acknowledges the very substantial research and editing assistance of her associate, Katie Allan BA LLB(Hons) and the editorial and secretarial assistance of her executive assistant, Andrea Suthers.

2. Above.

3. Section 349(1) and (2)(a), Criminal Code 1899 (Qld).

4. Section 349(3), Criminal Code.

5. R v KU & ors; ex parte A-G (Qld) [2008] QCA 154 at [39].

6. Queensland Judgments, http://www.sclqld.org.au/qjudgment/

7. Asia Pacific Awards 2009, Best Feature Film; Australian Screen Editor’s Guild Awards 2009, Best Editor, Feature (Rowland Gallois); 17th Art Film Fest, Slovakia, Blue Angel Award for Best Director, AWGIE Awards, Feature film screenplay (original); Kate Challis RAKA Award for Indigenous Script Writing; St Tropez Film Festival, France, Best Female Actor (Marissa Gibson), Best Male Actor (Rowan McNamara), Around the World in 14 Films — Berlin Independent Film Fest, IFA Cultural Film Award.

8. Best film, director, script, cinematography, sound, young actors (jointly awarded to Marissa Gibson (Delilah) and Rowan McNamara (Samson)) and an AFI members’ choice award.

9. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Population Characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2006, ABS cat no 4713.0 (2008) at 12 (Notes 9 to 43 cited in Australian Human Rights Commission, A statistical overview of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (2008) <http://www.hreoc.gov.au/social_justice/sj_report/sjreport08/downloads/appendix2.pdf>.

10. Above at 19.

11. Above.

12. Above at 13.

13. Above.

14. Above at 35 — 37.

15. Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Survey 1994 — Detailed Findings, ABS cat no 4190.0 (1995) at 4; Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2004-05, ABS cat no 4715.0 (2005).

16. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Bureau of Statistics, The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2008, ABS cat no 4704.0 (2008) at 154.

17. Australian Human Rights Commission, A statistical overview of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (2008) <http://www.hreoc.gov.au/social_justice/sj_report/sjreport08/downloads/appendix2.pdf> at 290.

18. Above; I Ring and D Firman, ‘Reducing Indigenous mortality in Australia: lessons from other countries’ (1998) 169 Medical Journal of Australia 528-533.

19. The State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, Report published by the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, UN Doc No ST/ESA/328 (2009), Ch 5 at 159.

20. Above at 156-7.

21. Australian Human Rights Commission, A statistical overview of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (2008) <http://www.hreoc.gov.au/social_justice/sj_report/sjreport08/downloads/appendix2.pdf> at 296.

22. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Population Characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2006, ABS cat no 4713.0 (2008) at 103.

23. Above at 107.

24. Above at 81.

25. Above.

26. Australian Human Rights Commission, A statistical overview of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (2008) <http://www.hreoc.gov.au/social_justice/sj_report/sjreport08/downloads/appendix2.pdf>at 298.

27. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Bureau of Statistics, The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2008, ABS cat no 4704.0 (2008) at 16-17.

28. Above at 24 — 25.

29. Above at 30.

30. Above at 40-41.

31. Above at 41.

32. Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, National Report (1991) Vol 1 at [9.3.1].

33. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Prisoners in Australia 2008, ABS cat no 4517.0 (2008) at 22,

Table 8.

34. Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2007, Productivity Commission (2007) at 128.

35. Above at 129.

36. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Bureau of Statistics, The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2008, ABS cat no 4704.0 (2008) at 225, Table 11.4.

37. Australian Human Rights Commission, A statistical overview of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (2008) <http://www.hreoc.gov.au/social_justice/sj_report/sjreport08/downloads/appendix2.pdf> at 309.

38. Above.

39. Australian Human Rights Commission, A statistical overview of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (2008) <http://www.hreoc.gov.au/social_justice/sj_report/sjreport08/downloads/appendix2.pdf>at 298.

40. Telethon Institute for Child Health Research & Kulunga Research Network, University of Western Australia, Western Australia Aboriginal Child Health Survey (2002).

41. Above.

42. Above.

43. Above.

44. Donna Craig, Gary D Meyers and Garth Nettheim, Indigenous peoples and governance structures: a comparative analysis of land and resource management rights (2002) at 212.

45. Above at 213.

46. Above at 209 — 215.

47. The Alta-Kautokeino Watercourse Conflict, Decision of the Supreme Court of Norway, 26 February 1982, Norsk Retstidende (1982) at 241.

48. Tom Svensson, ‘Right to self-determination: A basic human right concerning cultural survival. The case of the Sami and the Scandinavian State’ in Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, Human rights in cross-cultural perspectives (1995) 363, 372, cited in Donna Craig, Gary D Meyers and Garth Nettheim, Indigenous peoples and governance structures : a comparative analysis of land and resource management rights (2002) at 213.

49. Mabo v The State of Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1.

50. Above, Brennan J at 58, Deane and Gaudron JJ at 109, Toohey J at 180, 182; Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds) The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (2001) at 496.

51. Donna Craig, Gary D Meyers and Garth Nettheim, Indigenous peoples and governance structures: a comparative analysis of land and resource management rights (2002) at 215.

52. Above at 212.

53. European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages [1992] COETS 6 (opened for signature 5 November 1992).

54. Statistics Norway, Sami Statistics 2010 (2010).

55. Above.

56. Above.

57. Swedish Institute, Factsheet: The Sami People in Sweden (1999) <http://www.samenland.nl/lap_sami_si.html>

58. The Finnish Sami Parliament, ‘Land Rights, Linguistic Rights and Cultural Autonomy for the Finnish Sami People’ (1997) 33/4 Indigenous Affairs.

59. Statistics Norway, Sami Statistics 2010 (2010).

60. Anne Lene Turi, Margrethe Bals, Ingunn B Skre and Siv Kvernmo, ‘Health service use in Indigenous Sami and non-Indigenous youth in Norway: A population based survey’ (2009) 9 BMC Public Health 378.

61. Siv Kvernmo, ‘Mental health of Sami youth’ (2004) 63 (3) International Journal of Circumpolar Health 221.

62. Lander Arbelaitz, Resource Centre for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, The Silent Revolution (2007) <http://www.galdu.org/web/index.php?artihkkal=344&giella1=eng>; See also Donna Craig, Gary D Meyers and Garth Nettheim, Indigenous peoples and governance structures: a comparative analysis of land and resource management rights (2002) at Ch 10.

63. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, GA Resolution 61/295, 61st Session, UN Doc No A/RES/61/295 (opened for signature 13 September 2007).

64. See Arts 3-5.

65. Art 46.

66. Commissioner Mick Gooda, ‘The Practical Power of Human Rights’ (Speech delivered at the QUT Public Lecture Series 2010, Brisbane, 19 May 2010) at 4.

67. Above at 12.

68. National Human Rights Consultation Report (2010) Recommendation 16.

69. See, for example, Noel Pearson, ‘Native Tongues Imperilled’ in Up from the Mission (2009) at 344 — 347.

70. ‘A Peculiar Path that Leads Astray’ in above at 349-350.

71. ‘Our Right to Take Responsibility’ in above at 143-171.

72. Noel Pearson, ‘Radical Hope: Education and Equality in Australia’ (October 2009) Quarterly Essay No 35; Noel Pearson, ‘We need real reform for Indigenous public schooling’ The Australian, 25 August 2004; Noel Pearson, ‘A Charter for a brighter future’ The Weekend Australian, 28-29 November 2009; See generally the work of the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership on education <http://www.cyi.org.au/education.aspx>.

73. Tanya Chilcott, ‘Education promise for indigenous students’ Courier-Mail (Brisbane), 24 May

2010 at 3.

74. Tammy Williams, A strategic framework for effective indigenous mainstreaming (May 2010).

75. Above.

76. Above.

77. Tammy Williams, Geranium Consulting, Leadership & Managing Change (June 2008).

78. The chair of Australian Indigenous Studies in the Centre for Health and Society, School of Population and Health, University of Melbourne.

79. Marcia Langton, ‘The end of ‘Big Men’ Politics’ (2008) 22 Griffith Review at 13.

80. Above at 38.

81. See http://www.yalari.org/. See also Department of Education and Training (Qld), Indigenous Students Scholarships Database (2010) <http://education.qld.gov.au/students/grants/scholarships/docs/scholarship-database.doc>.

82. See Scholarships for Indigenous Students <http://www.jcu.edu.au/smd/prospective/JCUDEV_002306.html>.

83. Visiting scholar shares strategies for retaining Indigenous students (2007) <https://www.usq.edu.au/newsevents/usqnews/USQ%20News%202007/newsitems/news/pfalk>

84. For example, Bill Yidumduma Harney, senior lawman of the Wardaman People, recently painted a new work of art sharing the Law of the Wardaman People with Bond University law students and staff.

It is especially appropriate given tonight’s topic that I acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which this fine university stands: the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people. I respectfully note that long before James Cook University (JCU) was built here, and indeed for millennia before European settlement, the ancestors of the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people lived and prospered on this land. No doubt they held regular meetings with their Elders to discuss matters of community interest and concern, in essence not so very different to tonight.

It is especially appropriate given tonight’s topic that I acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which this fine university stands: the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people. I respectfully note that long before James Cook University (JCU) was built here, and indeed for millennia before European settlement, the ancestors of the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people lived and prospered on this land. No doubt they held regular meetings with their Elders to discuss matters of community interest and concern, in essence not so very different to tonight. Let me begin with the notorious case of KU & ors. Three young adult men and four youths pleaded guilty to the penile rape of a 10 year old girl in Aurukun. The adults were initially sentenced to six months imprisonment suspended immediately for 12 months, and the youths to 12 months probation without conviction. After the expiry of the appeal period, Tony Koch, writing for The Australian, and then the wider media, criticised the sentences. There was a public outcry throughout Australia and internationally. In February 2008, the Court of Appeal granted the Attorney-General an extension of time to appeal.2 Together with the Chief Justice and Justice Keane, I heard that appeal in June 2008. I found it distressing, despite my experience over 33 years as a criminal law barrister and a judge.

Let me begin with the notorious case of KU & ors. Three young adult men and four youths pleaded guilty to the penile rape of a 10 year old girl in Aurukun. The adults were initially sentenced to six months imprisonment suspended immediately for 12 months, and the youths to 12 months probation without conviction. After the expiry of the appeal period, Tony Koch, writing for The Australian, and then the wider media, criticised the sentences. There was a public outcry throughout Australia and internationally. In February 2008, the Court of Appeal granted the Attorney-General an extension of time to appeal.2 Together with the Chief Justice and Justice Keane, I heard that appeal in June 2008. I found it distressing, despite my experience over 33 years as a criminal law barrister and a judge. And now, from fact to fiction … the superbly crafted, confronting Warwick Thornton film Samson and Delilah. It won accolades in Australia and internationally7 including the 2009 Camera d’Or at the iconic Cannes Film Festival. It scooped the prizes at the 2009 Australian Film Institute Awards.8

There were many powerful moments: Delilah’s unfair beating by the old Indigenous women; her chilling rape in Alice Springs; and the sickening thud as Delilah, off her tree from petrol-sniffing, was struck by a car. But I especially remember when the talented but penniless fringe-dwelling Indigenous artist, Delilah, entered a coffee shop to sell a painting. The discomfort and embarrassment of the white, prosperous, middle class non-Indigenous clientele was palpable as they tried to ignore the unignorable Delilah until the proprietor removed her from the coffee shop and their lives. Why was I so affected by this scene which did not have the physical violence of the other memorable vignettes? I was affected because I saw myself in those white, prosperous middle class Australian coffee drinkers. I was affected because I empathised with Delilah and knew that, but for an accident of birth, I may have been Delilah. I was affected because I knew that film-lovers all over the world would ask how white, prosperous, middle class Australian coffee drinkers like me could allow this to happen…

But does one notorious court case and a powerful film show the real picture of Indigenous Australia? Of course not. Let’s look at the hard data.

And now, from fact to fiction … the superbly crafted, confronting Warwick Thornton film Samson and Delilah. It won accolades in Australia and internationally7 including the 2009 Camera d’Or at the iconic Cannes Film Festival. It scooped the prizes at the 2009 Australian Film Institute Awards.8

There were many powerful moments: Delilah’s unfair beating by the old Indigenous women; her chilling rape in Alice Springs; and the sickening thud as Delilah, off her tree from petrol-sniffing, was struck by a car. But I especially remember when the talented but penniless fringe-dwelling Indigenous artist, Delilah, entered a coffee shop to sell a painting. The discomfort and embarrassment of the white, prosperous, middle class non-Indigenous clientele was palpable as they tried to ignore the unignorable Delilah until the proprietor removed her from the coffee shop and their lives. Why was I so affected by this scene which did not have the physical violence of the other memorable vignettes? I was affected because I saw myself in those white, prosperous middle class Australian coffee drinkers. I was affected because I empathised with Delilah and knew that, but for an accident of birth, I may have been Delilah. I was affected because I knew that film-lovers all over the world would ask how white, prosperous, middle class Australian coffee drinkers like me could allow this to happen…

But does one notorious court case and a powerful film show the real picture of Indigenous Australia? Of course not. Let’s look at the hard data. The 2006 census revealed that Indigenous Australians comprise 2.3 per cent of the total population.9 Ninety per cent of those are Aboriginal, 6 per cent Torres Strait Islander and 4 per cent identified as both. Queensland’s Indigenous population is comparatively large.10 Twenty eight per cent of the total Australian Indigenous population lives in Queensland. They comprise 3.5 per cent of Queensland’s total population.11

Almost one-third of Indigenous people reside in major cities, 21 per cent in inner regional areas, 22 per cent in outer regional areas, 10 per cent in remote areas, and 16 per cent in very remote areas.12 In contrast, 69 per cent of the non-Indigenous population live in major cities, with less than 2 per cent in remote and very remote areas.13

Fifty-six per cent of Indigenous respondents living in remote areas spoke an Indigenous language. Indigenous languages are more likely to be spoken in central and northern Australia than in the south.14 Most Indigenous people identified with a clan, tribal or language group.15 This data suggests that culture and language remain significant to Indigenous Australians.

The health of Indigenous Australians appears generally poorer than that of non-Indigenous Australians. One measure of health is life expectancy. Indigenous life expectancy in 2003 was 17 years less than that of the general Australian population.16 The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) notes that 30 years ago, life expectation for Indigenous peoples in Canada, New Zealand and the United States of America, though well below that of the general non-Indigenous populations of those countries, was comparable to that of Indigenous peoples in Australia.17 Concerningly, the data suggests that Indigenous people in Australia now have life expectancies more than 10 per cent less than Indigenous peoples in those countries.18 The United Nations recently noted that the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous life expectancy in Australia is higher than that of many poorer countries such as Panama, Mexico and Guatemala.19 Indigenous infant mortality between 2001 and 2005 was also high: about 6 per cent of total Indigenous deaths, whereas infant deaths in the general population were less than 1 per cent of total deaths.20

Petrol-sniffing featured in the fictional Samson and Delilah. The HREOC encouragingly reports:

The 2006 census revealed that Indigenous Australians comprise 2.3 per cent of the total population.9 Ninety per cent of those are Aboriginal, 6 per cent Torres Strait Islander and 4 per cent identified as both. Queensland’s Indigenous population is comparatively large.10 Twenty eight per cent of the total Australian Indigenous population lives in Queensland. They comprise 3.5 per cent of Queensland’s total population.11

Almost one-third of Indigenous people reside in major cities, 21 per cent in inner regional areas, 22 per cent in outer regional areas, 10 per cent in remote areas, and 16 per cent in very remote areas.12 In contrast, 69 per cent of the non-Indigenous population live in major cities, with less than 2 per cent in remote and very remote areas.13

Fifty-six per cent of Indigenous respondents living in remote areas spoke an Indigenous language. Indigenous languages are more likely to be spoken in central and northern Australia than in the south.14 Most Indigenous people identified with a clan, tribal or language group.15 This data suggests that culture and language remain significant to Indigenous Australians.

The health of Indigenous Australians appears generally poorer than that of non-Indigenous Australians. One measure of health is life expectancy. Indigenous life expectancy in 2003 was 17 years less than that of the general Australian population.16 The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) notes that 30 years ago, life expectation for Indigenous peoples in Canada, New Zealand and the United States of America, though well below that of the general non-Indigenous populations of those countries, was comparable to that of Indigenous peoples in Australia.17 Concerningly, the data suggests that Indigenous people in Australia now have life expectancies more than 10 per cent less than Indigenous peoples in those countries.18 The United Nations recently noted that the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous life expectancy in Australia is higher than that of many poorer countries such as Panama, Mexico and Guatemala.19 Indigenous infant mortality between 2001 and 2005 was also high: about 6 per cent of total Indigenous deaths, whereas infant deaths in the general population were less than 1 per cent of total deaths.20

Petrol-sniffing featured in the fictional Samson and Delilah. The HREOC encouragingly reports: In 1989, Norway established a “Sami parliament” to deal with discrete Sami matters. Importantly, this parliament is not concerned with the establishment of an independent Sami state but only with the protection of the traditional Sami lands against exploitation, and the clear recognition of traditional Sami hunting, fishing and reindeer herding rights.52

In 1989, Norway established a “Sami parliament” to deal with discrete Sami matters. Importantly, this parliament is not concerned with the establishment of an independent Sami state but only with the protection of the traditional Sami lands against exploitation, and the clear recognition of traditional Sami hunting, fishing and reindeer herding rights.52