Issue 57: Oct 2012, Speeches and Legal Articles of Interest

Thank you, Mr Callinan, for your generous words of welcome and introduction. Good afternoon, your Honours, ladies and gentleman.

The subject of my speech today is The Griffith Court, the Fourth Commonwealth Attorney-General and the ‘Strike of 1905.’

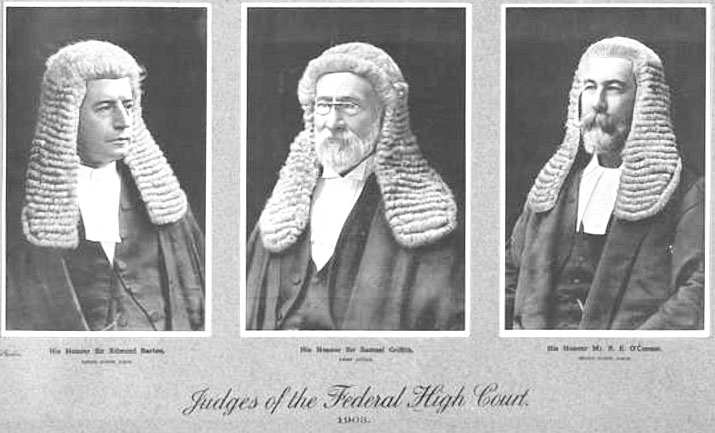

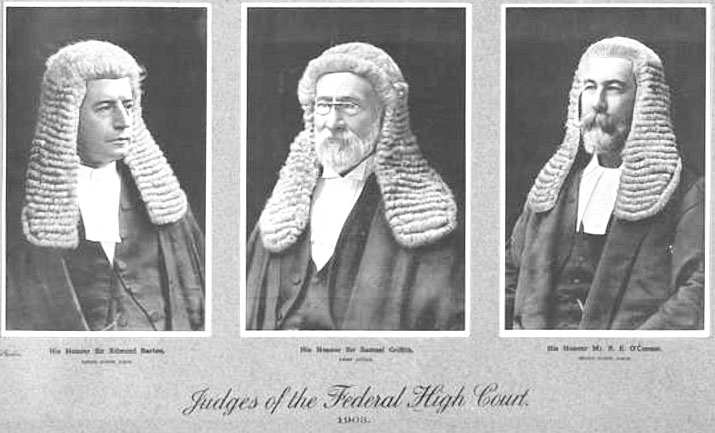

The Court’s choice of its original three members, Chief Justice Samuel Walker Griffith and puisne Justices, Edmund Barton and Richard Edward O’Connor, as John Williams has observed, was not as obvious as it may have initially seemed.1Â ‘The list of potential candidates, especially given the intimacy that many [of them] had with the drafting of the [Australian] Constitution, was long’,2Â and even when the appointments of the Judges was finally announced, the composition of the Court was not without its critics.3Â

Nonetheless, the newly appointed first Chief Justice would go on to silence any criticism. Griffith would ensure from the outset that the High Court at the apex of Australia’s judicial hierarchy would establish the foundations necessary for the Court’s day to day running practices along with its recognition as the pre-eminent legal authority in a newly federated Commonwealth.4

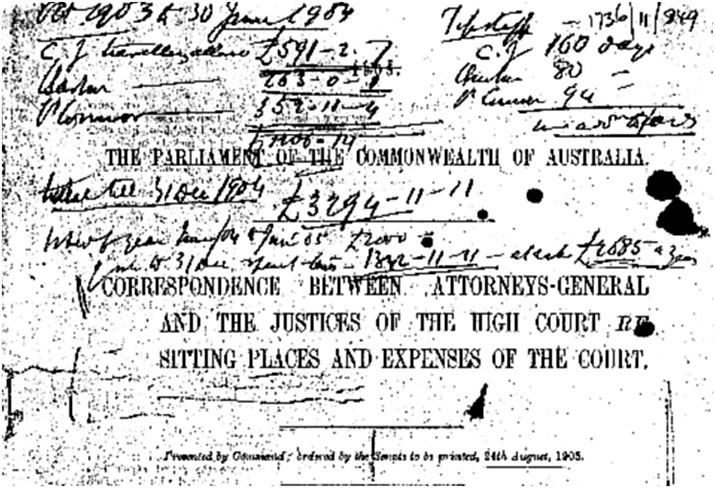

On taking office the Chief Justice, facilitated by section 47 (i) of the Commonwealth Judiciary Act 1903,in the absence of a pension, was paid a salary of ‘[t]hree thousand five hundred pounds a year’.5Â The other Justices, [t]hree thousand pounds a year’.6Â This was initially thought to be a generous; being assessed at the time as ‘more than twenty-seven times the basic wage’,7Â but became substantially eroded when forty-four years later, this remuneration, was increased for the first time in September 1947.8

Further in accordance with section 12 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth),9Â the Justices travelled between most capital cities including Hobart by train or steamship in the Court’s first year of operation accompanied by their own personnel, comprising three Associates and three Tipstaffs.10Â These travelling expenses, exclusive of salary, were met by the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department and were computed from the Judges’ homes. The Chief Justice from his home state of Queensland, and the two other Justices, from their homes in New South Wales. Finally,from the words of a 1905 letter written by Samuel Griffith, of those early days on circuit he recalled; ‘it has fortunately happened that we [the Judges] are on terms of personal friendship’,11Â and ‘on most but not all occasions [have] been able to reside together’12Â occupying ‘lodgings…as may be expected to fill the office of a Justice’.13Â

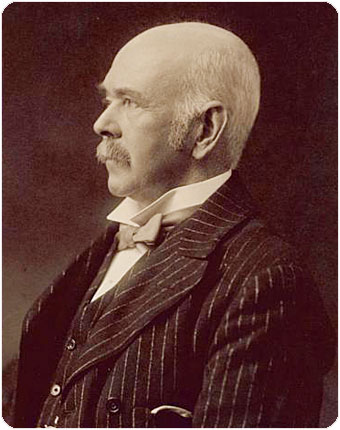

In December 1904, however, after less than 15 months of operation, the question of High Court expenditure with regards to its running costs came to the attention of Australia’s fourth Commonwealth Attorney-General, Josiah Henry Symon.

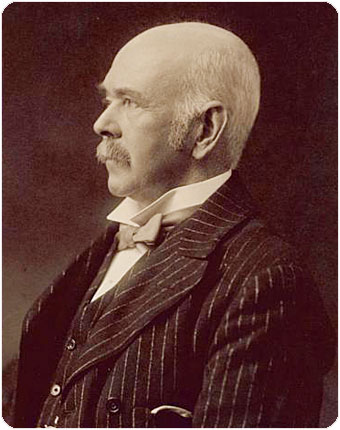

Symon was of Scottish origin14 and a wealthy rural landowner residing in South Australia.15 He was a politician and winemaker and was also considered one of Australia’s early scholarly authorities on the works of Shakespeare.16Â

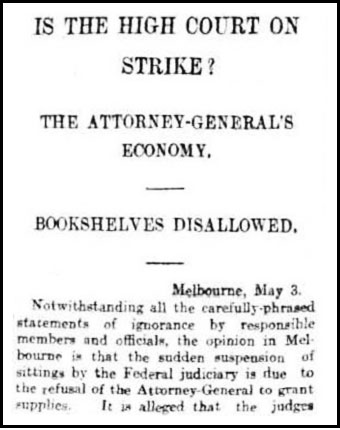

He matched his political finesse with the skills of an exceptional lawyer,17]but when he became the fourth Commonwealth Attorney-General in Australia’s first Coalition Government, the Reid-McLean Ministry,18 his scrutiny of the High Court’s expenses resulted in a bitter, escalating and ultimately public confrontation with Australia’s original High Court.19Â This culminated in May 1905, when the High Court adjourned proceedings and went on ‘strike’20Â due to the continued uncertainty surrounding the payment of its travelling expenses, accommodation costs and the provision of staff to run the Court.

An event variously referred to as a ‘trial of strength between…Samuel Griffith and …Josiah Symon’, a ‘controversy’, and a ‘deadlock’ remains exceptional in the High Court’s history. For the Chief Justice whose outstanding command of the law was seen as one of ‘the most powerful guarantee of the High Court’s success,’21 it would leave a marked contribution towards shaping both the independence of the Court and its future operation which, in a modified way continues to this day.

As a further observation, all three members of the High Court as well as Attorney-General Symon, had been involved tirelessly, though by no means harmoniously,22Â throughout the Convention Debates of 1890’s.23

As Federation Fathers they had shaped the bill line by line that would eventually become Australia’s Constitution. This came to its successful conclusion when, on January 1 1901, ‘[a]n Act to Constitute the Commonwealth of Australia’,24Â brought into being an ‘independent sovereign nation in the twentieth century’.25

Finally, other concepts relating to the role of Australia’s judiciary entertained by Josiah Symon at the time of federation would also prove to be contentious; that the original High Court be the final Court of appeal26Â and also that it be created with a permanent seat like the US Supreme Court.27 Symon’s arguments against Privy Council appeals had been met with particular resistance from Samuel Griffith in 1900,28Â and the courts practice of undertaking sittings in various states as already indicated, had been facilitated by section 12 of the Judiciary Act 1903(Cth). It can also be added that Josiah Symon had been one of the many candidates considered, but not chosen for a place on Australia’s first High Court.29 So instead, upon becoming the fourth Commonwealth Attorney-General, he found himself as the head of a department that had already started to scrutinise the cost of running the newly formed High Court.30

Thus, in short,it was a combination of intense personal differences between individuals, now appointed to the highest levels both politically and judicially, who also possessed contending ideals concerning the judicial function of a new Court at a time when the ‘expectations for the Court’s success were very high’,31Â were sufficient to provide the impetus for what would become an escalating, protracted conflict between the Executive and the Judiciary. The dispute was monitored closely by the Australian press32Â and deemed important enough for some members of the public to write poetry about the disagreement to their local newspapers.33Â

Boiling oil, boiling oil, that’s no legal fiction,

Would you not decide in your appellate jurisdiction

That interfering people who are rude about expenses,

If dipped in red-hot kerosene would soon regain their senses?34

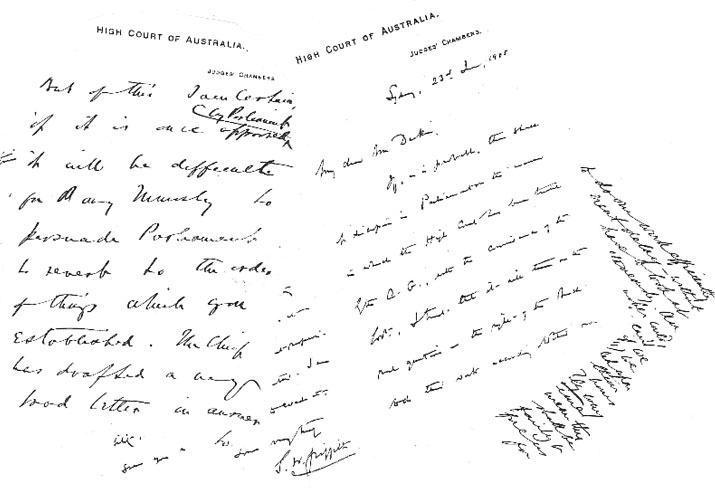

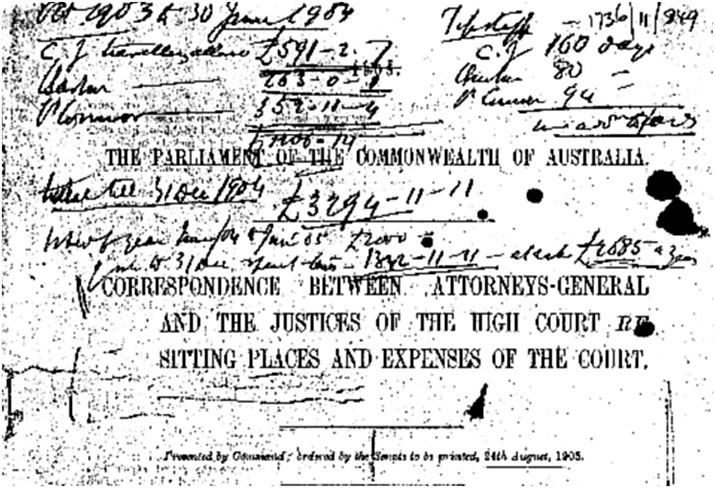

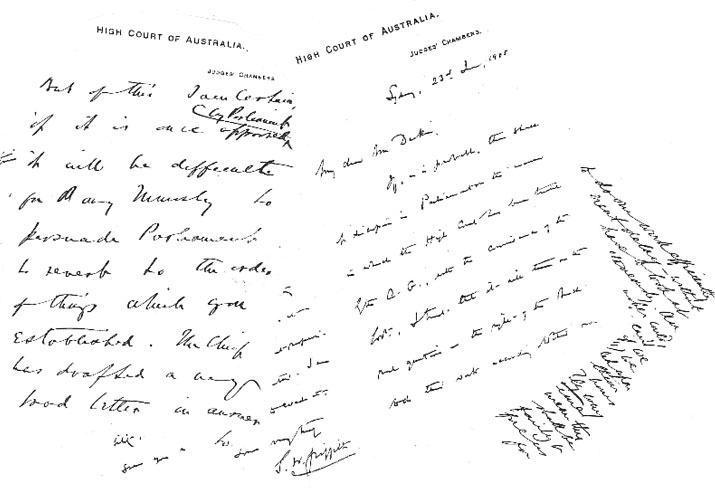

Surviving archival material reveals the disagreement was fought out primarily through reams of correspondence including telegrams.35Â Preserved in original handwritten form or typeset, most of these were later published as part of a Parliamentary enquiry.36Â

Particularly striking are the eloquent, often long letters passed between Attorney-General Symon and Chief Justice Griffith on behalf of the Court. According to Robert Garran, he recalled that the correspondence was for Symon’s part, considered to be of ‘threatening amazing proportions’37Â and according to another later commentator, the letters were ‘marked on both sides by suppressed fury, and deadly icy courtesy’.38Â

Therefore, when Josiah Symon became the Attorney General on August 18 1904, he also accepted the additional position he regarded as a much valued role, that of ‘the leader for the government in the Senate’.39Â It was at this time that he, and I quote from the Parliamentary Debates,‘found a pile of papers of considerable magnitude entitled “High Court expenditure and traveling expenses”’.40Â These documents again in his own words were ‘literally a legacy from the previous Government’.41

Significantly, the discovery of this correspondence demonstrates that Symon cannot solely be blamed for the tumultuous events that took place between the months of August 1904 to July 1905.42Â It had been his predecessor Henry Bourne Higgins on behalf of the Watson Government, who had commenced an investigation into the accumulating travelling expenses of the Court with a stated desire to ‘make other arrangements’.43 However, due to the subsequent pressure of Parliamentary business associated with a new government, including combating a vote of no confidence in the new Coalition two weeks after Parliament began sitting,44 Symon, ‘was unable at once to go into the matter fully’45Â and no further action was taken.

Towards the end of 1904, Chief Justice Samuel Griffith wrote directly to Prime Minister George Reid, following up on what he described as an earlier ‘conversation’,46Â indicating with some reluctance his intention to move from his home in Brisbane and take up permanent residence in Sydney. The other Justices of the Court already lived there and this was perhaps one way his travelling expenses could be reduced.47Â He also requested that his chambers in Sydney be furnished to accommodate his law library.48Â He exhorted the Prime Minister to seriously consider making Sydney the ‘Principal Seat of the Court’49Â on the understanding that all three Justices would continue to live in New South Wales as permanent residents.

When Griffith’s requests were brought to the attention of the Attorney-General, in a letter dated 2 December 1904,50Â it was Josiah Symon’s prompt and blunt response51 that turned any mere formalities into what one observer penned as a verbal ‘declaration of war’.52Â

Symon reminded Griffith of the Court’s earlier and unsuccessful attempts to negotiate satisfactory finances for travelling purposes, particularly for its Associates with previous Attorney-General, Higgins.53Â He indicated in his words that ‘the travelling expenses accrued by the Bench in less than a year had ‘attained a magnitude which … both inside and outside Parliament, has occasioned remark and evoked sharp criticism…and I feel sure I shall not look in vain to the Justices of the High Court to assist in securing a substantial reduction in those expenses’.54Â

Symon appealed to the Justices to consider his views about the need for greater financial efficiency and immediately targeted the ‘avoidable’55Â expenditure associated with the circuit practices of the Court as one way of controlling the costs currently imposed upon the Commonwealth.56Â Reflecting his personal sentiments expressed at the earlier Convention debates, he emphasised that the High Court as a circuit Court was unnecessary and that ‘the High Court qua Full Court ought not, unless under very exceptional circumstances, to incur any travelling expenses’.57Â He also insisted that the proper seat of the Court was Melbourne, because it was also the seat of the Commonwealth Government. He then went on and proposed that, from the beginning of January 1905, all travelling expenses were to be reduced. The starting point of computation would no longer be the Judges places of residence but from the principal seat of the Court. Each Justice would receive no more that a maximum of ‘three guineas’58Â a day for this purpose and that these costs also included those of his associate.59Â The request for shelving by the Chief Justice to accommodate his law library in his Sydney Chambers was subsequently deferred.60Â

In an immediate response on behalf of the Court, Griffith made it clear that he would become a formidable opponent.61 Described as possessing a‘cold, clear, collected and acidulated personality’62Â as much as Symon was depicted as ‘quarrelsome’63 the Chief Justice leapt to the defence of the Court’s independence suggesting that the High Court as a Court of Appeal and sitting in the state capitals was a practice that had been ‘adopted after full consideration and with warm concurrence of the Federal Government’.64Â Further, as far as the Chief Justice was concerned, the practice of a circuit Court had also ‘received the approval of public opinion throughout the Commonwealth’65Â and he felt justified in assuming that these arrangements, which could only be altered by ‘Rule of Court or Statute’,66Â ‘would not be disturbed’.67

During the early part of 1905, in letters throughout January and February,68 Symon persisted with the necessities of reducing the ‘burdensome expenditure of the High Court’.69Â His correspondence became increasingly personal and combative. In an attempt to justify his current position on the matter he said, in part, ‘it would not be in the interests of the Court itself, or of the people of Australia if the Attorney-General of the day did not maintain a rigorous control over its non-judicial action and its expenditure so far as it comes within the cognisance of this Department and the sphere of the executive. I intend to do my duty in this respect’.70Â

Prime Minister Reid, well aware of the mounting quarrel, through discussions with the Judges and his Attorney-General on separate occasions,71Â as well as engaging in personal correspondence with the latter,72Â intervened and offered a compromise. He suggested that the circuit system ought to be simplified so that New South Wales and Queensland appeals would be heard in Sydney and all other appeals ‘at the principal seat of the Court in Melbourne’.73

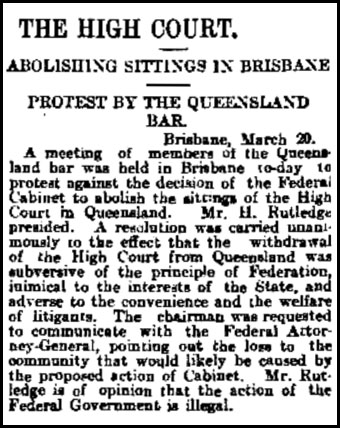

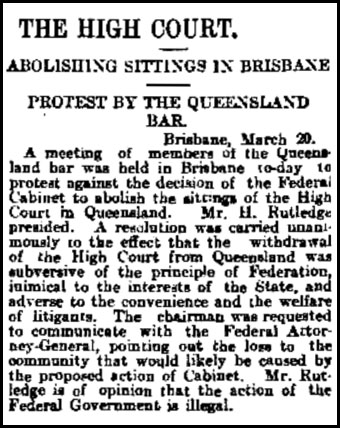

There is no evidence that the Justices made any formal response to this suggestion74Â but opposition from the states and the legal profession to the possibility of curtailing the practice of circuits soon began to emerge in the newspapers.

In particular, Mr H Rutledge, on behalf of the Queensland Bar Association, made it known that the Association had met to protest about the ‘Federal Cabinet deciding to abolish the sitting of the High Court in Queensland’.75

He also added that in their opinion, ‘the withdrawal of the High Court from Queensland was subversive of the principle of Federation … and averse to the convenience and the welfare of litigants.’76

Rutledge also took the opportunity in The Brisbane Courier on the same day, to iterate the reasons for the Queensland Bar’s protest, saying in a similar vain that ‘to restrict the sittings of the High Court’77Â would ‘shift the burden of expenditure in connection with litigation from the shoulders of the Commonwealth as a whole to the shoulders of individual litigants’.78

The correspondence between the Attorney-General and the High Court continued and perhaps if Reid’s compromise had been offered earlier it may well have been accepted.79Â However, Griffith had threatened to ‘take an early opportunity’80Â to provide the public with an explanation of the absence of his law library from his Sydney chambers. Symon remained unmoved by any threats, believing with equal resolve that his policy was correct.81Â

In a long, detailed and ‘angry’82 letter,83 towards the end of February, the Attorney-General reminded the Justices of the ‘excessive’ sum of £2, 285 that the Court’s first fifteen months of sittings had cost the Commonwealth and iterated his previous position. As a ‘trustee for the public in relation to High Court expenditure’,84 he had every intention of continuing with his economic measures in order to ‘prevent its recurrence’.85 Symon went on to say that he regretted the attitude of antagonism and unwillingness the Justices had adopted in the matter of circuits, and again emphasised that it was ‘circuits which gave occasion for swollen travelling expenses’.86 He was indignant and unable to understand how the Chief Justice could doubt that ‘Parliament, rightly following the Constitution [had] never contemplated circuits of any sort’.87Â

In early March 1905, responding defiantly to Symon’s unrelenting ‘arguments’,88Â the Justices left for circuit in Hobart but on their return the Court promptly sent another letter to the Attorney-General. It urged the view that all his cost cutting measures were improperly seeking to interfere with judicial independence.89Â A week earlier, they had indicated in pointed terms that the tone Symon adopted was ‘unusual in official correspondence’90 and that a ‘more careful perusal of our letters would have enabled you to avoid some errors into which you have fallen’.91Â They found his constant intrusion, ‘intolerable’.92 Symon, who perhaps would have been ‘wiser to restrain himself’,93Â chose instead to do otherwise.

Copies of the Attorney General’s letters were sent by the Court via their private correspondence to former Prime Minister Alfred Deakin to ensure that he was informed of ‘everything [that had occurred] so far’.94Â Edmund Barton was specific with his request to Deakin. ‘If you find what seems to you as a solution please let me have it’.95

Deakin’s response was one of disbelief. He stated ‘I cannot tell you how [Symon’s] letters shocked me…make no mistake they are written with fiendish ingenuity and sinister powers…Still at any cost to yourselves, to your sentiments of honour and dignity, for the sake of the Commonwealth and the High Court this correspondence ought to be destroyed’.96

Justice O’Connor also expressed his regret that the correspondence could not be withdrawn, as it was ‘too late’.97Â A few days later, O’Connor wrote again to Deakin. He expressed his concern regarding the necessity of settling the matter with the Attorney-General, especially if in the future, when the number of Justices were increased from three to five, ‘Symon himself became a member of the Court’.98Â

Finally, Edmund Barton also had his own reflections to add:

One feels all this bitterly. We are in every way degraded and humiliated by this unspeakable scoundrel: and if Australia offers the Judges of her one and only national Court to be treated thus she will deserve as she has not yet done the scoffs and jibes of the English speaking world. My wife wishes me to resign rather than submit to any further indignity but at least I shall wait to see whether Parliament adopts or condones, the outrage we have suffered, of which every day brings a new one in the shape of an insulting letter.99Â

Despite the conflict, The High Court continued sitting. Griffith wrote to Symon to inform him that the Full Court intended to go to Brisbane and asked for a courtroom to be placed at the High Court’s disposal.100Â In a calculated attempt to escalate the dispute, Symon refused.101] Furthermore, literally with one long sweep of a pen, in this letter dated 26 April 1905, Symon opened up more areas of bitter contention. He notified Griffith that travelling costs would be limited to the provision of one associate and one tipstaff, rather than the customary three associates and three tipstaves.102 This decision, has since been regarded by one historian, as rather a deft move because both Griffith and Barton had sons for associates.103Â

Finally, Symon suggested that the number of telephones in the chambers of all Justices and their associates in Sydney be reduced from five to one, and payment for telephones in the private residences of the Justices would be discontinued.104Â Moreover, Symon refused reimbursement for the cost of any additional traveling expenses incurred by the Justices outside the standard use of their government-issued railway passes.105Â He also requested that detailed information be supplied to him about all the current costs associated with running the Court.106

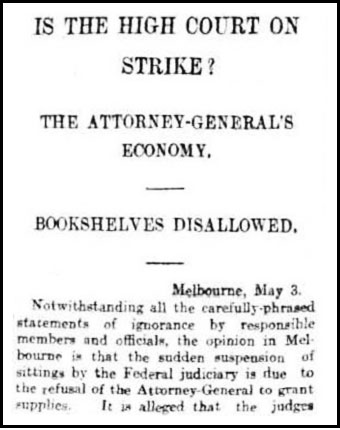

According to RB Joyce, a contemporary commentator, these particularly strident proposals proved to be the last straw.107Â The Court moved swiftly to bring the details of the crisis to public attention. O’Connor was due to hear a case concerning ‘Alleged Customs Frauds’ in Melbourne on 1 May 1905,108Â but the Justices had met in Sydney on the preceding Saturday and decided to suspend the sitting. The decision made newspaper headlines around the country.109

On hearing about the adjournment, Symon, in a state of high agitation, sent an urgent telegram to O’Connor: ‘I shall, therefore, be obliged if you will state to me the reason for the adjournment of the Court, and also whether you propose to proceed with the trials next Tuesday … forgive my pointing out the importance of an immediate reply.’110

Griffiths’ response on behalf of the Court was short and to the point. He defended the High Court’s action as a necessary defence of judicial independence. In part he stated, ‘We cannot recognise your right to demand the reasons for any judicial action taken by the Court, except such request as may be made by any litigant in open Court.’111Â

Symon, in a frustrated response scribbled on a scrap of paper: ‘How can any Ct. because of disagreement as to Hotel expenses go on strike? … no wharf labourers union do such thing.’112Â

Days before the dispute ended however, Griffith had the final say. ‘When we accepted our offices we did so with an assurance that the Executive Government of the Commonwealth, not reduced to writing, but carried into effect by executive Action, that the Government would provide such facilities for the maintenance of the dignity of our office, and the efficient discharge of our duties as are usual in Australia…’113

On 5 July 1905, as suddenly as the dispute had begun, it was over. Prime Minister George Reid resigned. The lack of support for his Coalition party in Parliament had meant he was unable to withstand a challenge from the Opposition with regards to the threat his proposed legislative reform would have for the future of protective tariffs in Australia.114Â

Alfred Deakin was sworn in as Prime Minister for the second time and Isaac Isaacs as the new Attorney-General. Isaacs wrote to Griffith less than a week later and in correspondence throughout July and August,115Â the Government was able to offer a ‘satisfactory and permanent solution of the matters agitated’.116

The Court would continue its practice of sitting in each state capital ‘as may be required’,117Â the Government would have full confidence in ‘their Honours’ wisdom’118Â with regards to travelling expenses, the numbers of associates and tipstaves would not be reduced, and the ‘trivial matter’119Â of shelving was attended to. The affair had ended.

Griffith was delighted. He wrote, ‘On behalf of my learned colleagues and myself I have pleasure in saying that we concur in the opinion of the Government that the conclusions set out in your letter constitute a satisfactory, and, as we trust, a permanent solution of the matters in question.’120

In an undated Memorandum prepared for Cabinet,121 Symon provided a brief insight into the reasons for his actions. He felt it had been ‘incumbent upon me…as well as in discharge of my duty as Minister as the head of the [Attorney-General’s] Department to strictly scrutinise the High Court expenditure and to devise if necessary, plans for its reduction’.122Â Yet, ironically at no time in undertaking his duties did he see his actions as interfering with the function of the judiciary. On the contrary, at a later date he explained to the Senate that in his view the ‘High Court in its judicial capacity, is above all executive interference and executive criticism, as it ought to be; but in regard to its administrative position…it is just as much subject to the control of the Executive and ought to be so, as any other department in the Public Service’.123Â Significantly, Symon in defeat also admitted that he had ‘been proud to discharge’124Â his duties as leader for the Government in the Senate, but with regards to his duties as Attorney- General, he remained silent.

Now, over a century later, the same question is posed as that of a letter to the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald on June 13 1905.125Â Can it be said that ‘too much has been made of too little?’ in considering something about the nature of this bitter and protracted debate and the ensuing High Court strike of 1905?

Symon’s political and personal embarrassment as Australia’s fourth Commonwealth Attorney-General quashed any aspirations he may have had for a future place on the High Court bench.126Â Yet, for all the turbulence he had caused, both for the Executive and the Judiciary, his actions were not without public support.127 Josiah Symon left a positive and enduring legacy alluded to at the introduction to this speech.

He was remarkable not just for his contribution to the development of Australia’s early legal profession in his home state of South Australia, but additionally, for his dedication to the federal cause. Importantly, although somewhat overshadowed by his confrontation with the High Court, during his brief time as the Attorney-General, Symon was instrumental in giving life to the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act,128 where the regulation of industrial disputes had proved to be the downfall of earlier Australian Governments.129

What of the conduct of the original High Court? Although neither of the parties in the dispute can be entirely ‘acquitted of all blame’,130 the narrative serves as a poignant illustration to acknowledge as the Bulletin did in 1903, that law and politics can “merge insensibly”’.131Â

The narrative also serves as a reminder to look beyond the robust exchanges and examine the context in which these exchanges occurred.

Griffth’s resolve to protect the judicial autonomy of the Court laid down an important marker in the development of the Commonwealth of Australia as a new polity.His actions between August 1904 and July 1905 provided a firm foundation ‘on which the Court was able to build on in later years’132Â and consolidated the pattern of the Court’s sitting practice that remains to this day as an important symbol of the parity of the states within the commonwealth.133

Perhaps too there is something uniquely Australian that so important a principle as judicial independence should be guaranteed in such a curious manner.

This Antipodean story of judicial assertion took place just over a century after Chief Justice John Marshall established the judicial supremacy and independence of his Supreme Court in the United States in the seminal case of Marbury v Maddison (1803).134 By placing their reputations and the institution at risk through a Judicial strike, Australia’s High Court Justices ‘validated their own Court’s claim to supremacy in a newly emerging polity and [in the twenty-first century,] we remain the beneficiaries of their courage’.135Â

Thank you for the honour of presenting the Sir Harry Gibbs Oration Lecture for 2012.

Dr Susan Priest

Photos courtesy of National Library of Australia

Footnotes

- JM Williams, One Hundred Years of the High Court the Trevor Reese Memorial Lecture 2003, 10.

- Ibid.

- George Reid reportedly denounced the appointment of Edmund Barton, Ibid, 12 and Josiah Symon was highly critical of both the appointment of Griffith and Barton: Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 24 September 1903, 5440 (Josiah Symon, Senator); ‘What Quiz Thinks’ date and author unknown, in the Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/3/14/20.

- H Gibbs, ‘Griffith, Samuel Walker’, in T Blackshield, M Coper and G Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia ( Oxford University Press, 2001) 310.

- Section 47 (i); See also section 72 of the Australian Constitution that guarantees security of ‘tenure and remuneration’.

- Ibid.

- G Winterton, Judicial remuneration in Australia (Australian Institute of Judicial Administration Incorporated, 1995) 38.

- Ibid.

- Section 12 states: ‘Sittings of the High Court shall be held from time to time as may be required as the principal seat of the Court and at each place at which there is a District Registry’.

- Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/862. Letter S Griffith to J Symon, 14 June 1905.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See generally the Symon Papers NLA MS 1736.

- The State Library of South Australia (SLSA) PRG 249 refers to Symon’s home ‘Manoah’ as being large and impressive and set in the Adelaide Hills on approximately 43 acres.

- See JH Symon, Shakespeare at Home (Adelaide, 1905) and Shakespeare the Englishman (Adelaide,1924).

- Symon’s legal skills were so esteemed that the dignified title of jurist was seemed to be more appropriate. See Author Unknown, ‘Eminent Federalists Senator Sir Josiah H Symon KC KCMG’ in United Australia January 20, 1902, 12.

- So called because it was the first Federal coalition, comprising the two Non-Labor parties of Australia’s tripartite Parliament in the House of Representatives consisting of a shared partnership headed by George Reid and supported by his Free Traders with a group of Liberal Protectionists led by Allan McLean.

- G Souter, Lion and Kangaroo; the Initiation of Australia (Text Publishing, first published 1976, 2000ed) 110-114.

- The use of the term ‘strike’ to describe the High Court adjournment in May 1905 was penned by Symon in a letter to Prime Minister George Reid on May 22 1905. See Symon Papers NLA MSS 1736 11/591. For further discussion about judicial strikes in other countries see G Winterton, above n 7,1-2.

- JM Bennett Keystone of the Federal Arch: A Historical Memoir of the High Court to 1980(AGPS, 1980) 21.

- Symon was greatly offended by Griffith’s criticism of the judiciary clauses drafted when Symon chaired the Judiciary Committee in Adelaide at the Adelaide Convention in 1897-98. See JM Williams, The Australian Constitution: A Documentary History (Melbourne University Press, 2005) 614-615.

- Â M Gleeson, ‘The Constitutional Decisions of the Founding Fathers’. The Inaugural Annual Lecture at the University of Notre Dame School of Law (Sydney) 27 March 2007.

- For a detailed discussion about ‘Aspects of the Commonwealth Constitution’ see M Gleeson, The Rule of Law and the Constitution (ABC Books, 2000) Chs 3 and 4.

- H Irving, ‘Constitution’ in B Galligan and W Roberts,The Oxford Companion to Australian Politics (Oxford University Press, 2007) 128.

- Symon held to this position in the 1890’s and perhaps even earlier. Appeals to the Privy Council were finally abolished with the implementation of the Australia Act 1986 (Cth). See T Blackshield and G Williams, Australian Constitutional Law and Theory (4thedFederation Press, 2006) 168, 600.

- WG McMinn, ‘The High Court Imbroglio and the Fall of the Reid-Mclean Government’ in Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society June 1978 Vol 64 Pt 1 14-16.

- JM Williams, above n 22, 614-15.

- Â The Bulletin Thursday 1 October 1903, 5.

- The Symon Papers contain copies of the correspondence between the former Attorney-General HB Higgins and the High Court in this regard.Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/720 and MS 1736/11/ 849.

- A Mason, ‘Griffith Court’ in T Blackshield, M Coper and G Williams (eds), above n 4, 311.

- The details of the incident can be found in most of Australia’s major Newspapers between the dates of August 1904 and as late as October 1905.

- See ‘Argument in the High Court’ in the Evening Journal, Wednesday 29March 1905, 1 and ‘The Passing Show’ by Oriel, in the Argus, Saturday 25 March 1905, 5.

- Ibid, Evening Journal.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736 11/720-735 and11/849-868.

- R Garran, Prosper the Commonwealth (Angus and Robertson, 1958)157.

- G Souter, above n 19, 110.

- Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates The Senate 24 August 1904 4284 (Josiah Symon, Senator).

- Â Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates The Senate 28 November 1905 5835 (Josiah Symon, Senator).

- Â Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates The Senate 28 November 1905 5835 (Josiah Symon, Senator).

- WG McMinn above n 27, 15.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/849.

- H Irving, ‘Sir George Houstoun Reid’ in M Grattan (ed), Australian Prime Ministers (New Holland Publishers, first published 2000, 2008 ed) 69-70. Reid survived the no confidence motion with a majority of two.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/461

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/721. The letter is dated 12 November 1904.

- Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates The Senate 28 November 1905 5837 (Josiah Symon, Senator). Symon claimed that from October 1903 until June 30 1904 Griffith drew traveling allowances of £591.2s.7d, Barton £263.0s.1d and O’Connor £352.11s.4d reflecting the extra traveling from his place of residence.

- Ibid.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736 11/146-146a and 11/721. The Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) under s 10 had specified the Principal seat of the High Court to be at the seat of Government. At the time of the dispute this was Melbourne, Victoria.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/849-50.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/850-851. The letter is dated 23 December 1904.

- G Souter above n 19, 111.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/850. The letter is dated 23 December 1904.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Symon indicated that at this stage in the dispute, it was ‘carte blanche in regard to the sum which might be certified.

- Ibid.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/851. The letter is dated 13 January 1905.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/850-851. The letter is dated 27 December 190

- A Deakin, And Be One People: Alfred Deakin’s Federal Story (Melbourne 1995) 12.

- R Garran, above n 37, 157.

- Above n 62, 850.

- Ibid. 851.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/723-733.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/852. The Letter is dated 31 January 1905.

- Ibid.

- Any written material to indicate what discussions the High Court may have had with George Reid could not be found but there is an indication that discussions took place between Symon and Reid. See the Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/461.

- Reid and Symon also wrote to each other on Jan 1 1905 and Jan 7 1905 respectively. See the Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/163-165.

- WG McMinn above n 27, 17.

- Nothing remains in the archival materials to indicate there was a formal response sent to Reid in this regard.

- ‘The High Court Abolishing Sittings in Brisbane Protest by the Queensland Bar’, The Advertiser (Adelaide), 21 March 1905 in Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/3/14/68.

- Ibid.

- ‘The High Court’s Sittings’, The Brisbane Courier (Qld), 21 March 1905 in Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/2/14 76-77.

- Ibid 77.

- WG McMinn above n 27, 17.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/725. The letter is dated 21 January 1905.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736 11/186-192.

- WG McMinn above n 27, 20.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/854-856. The letter is dated 22 February 1905.

- Ibid 854

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/856.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/857. The letter is dated 8 March 1905.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/733-734. The letter is dated 1 March 1905.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- WG McMinn, above n 27, 20.

- Deakin Papers NLA MS 1540/16/213. Letter E Barton to A Deakin, 11 January 1905.

- Ibid.

- JA La Nauze, Alfred Deakin(Melbourne University Press, 1965) 384.

- Deakin Papers NLA MS 1540/16/328. Letter R O’Connor to A Deakin, 8 June 1905.

- Deakin Papers NLA MS 1540/16/335. Letter R O’Connor to A Deakin, 12 June 1905.

- Deakin Papers NLA MS 1540/16/385. Letter E Barton to A Deakin, 21 June 1905.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/ 11/858.

- WG McMinn, above n 27, 20. See also the Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/858. The letter is dated 26 April 1905.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/858. The letter is dated 26 April 1905.

- WG McMinn above n 27, 20.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/858.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- RB Joyce, Sir Samuel Griffith (University of Queensland Press 1984) 264.

- See The Age (Melbourne), 10 May 1905,10.

- For example, headlines included a ‘High Court friction’ The Argus (Melbourne) May 24th 1905, 7. ‘High Court Deadlock’ The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW) May 24 1905, 8 and a ‘High Court Difficulty’ The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW) June 10th 1905, 11.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/ 11/859.

- Ibid.

- RB Joyce, above n 104, 265.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/864. The letter is dated 22 June 1905. There is an indication that after Reid’s resignation as Prime Minister Symon continued to write to Griffith as if he still had ‘the authority of an Attorney-General.

- WG McMinn, above n 27, 26. For more details, particularly about the political complexities associated with Reid’s defeat see also JA La Nauze, above n 94, Chapter 17.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/867-868. The letters are dated 12 July, 16 and 22 August 1905.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/868. The letter is dated 22 August 1905.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/ 11/869. The letter is dated 23 August 1905.

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/11/456-473

- Ibid 457.

- Â Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates The Senate 28 November 1905 5836 (Josiah Symon Senator).

- Â Commonwealth parliamentary Debates The Senate 5 July 1905 134 (Josiah Symon Senator).

- The Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/3/14/101.

- JA La Nauze, above n 93, 416.

- See the series of newspaper clippings found in the Symon Papers NLA MS 1736/3/14/ 80, 81 and 116;Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates The Senate 28 November 1905,5848 (Senator T Givens Queensland).

- See Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates The Senate 19 October 1904 5710 – 5732 for Josiah Symon’s second reading of the Bill.

- G Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901-1929 (MUP 1956) Chs 3 and 4 and R McMullin, So Monstrous a Travesty(Scribe, 2004) Chs 4 and 6.

- WG McMinn, above n 27, 28.

- The Bulletin in JM Williams, above n 1, 25.

- Ibid.

- G Del Villar and T Simpson, ‘Circuit System’ in T Blackshield, M Coper and G Williams (eds), above n 4, 96-97.

- 1 Cranch 137 (2 Law Ed. 60), 5 U.S. 137 (1803).

- S Priest, ‘Australia’s early High Court, the fourth Commonwealth Attorney-General and the ‘Strike of 1905’ in P Brand and J Getzler (eds), Judges and Judging in the History of the Common Law and Civil Law From Antiquity to Modern Times (Cambridge University Press 2012) 305.