The new courthouse, 1975

Fairness, like beauty, lies in the eye of the beholder[1].

The best years of our lives are often spent in pursuit of income. Yet in the justice system, we also give ourselves to a higher purpose – serving the community through fairness, justice, and the steady hand of the rule of law.

In courthouses across the state, justice demands more than skill and strategy. It requires a willingness to step into the darkest of human stories. Because the impact of crime does not end with the act itself. It lingers in shattered lives, traumatised families, and the legal processes that follow.

This year, we celebrate not only the Townsville courthouse as a building, but the extraordinary contributions made to justice and the community within its walls. The colourful characters, the stalwarts, the steady hands on the bench who have guided the flow of trials, given voice to the vulnerable, and ensured every party receives a fair hearing.

Completed in 1975 after years of lobbying, the new courthouse was so long promised that retired Justice R.J. Douglas – the former Northern Judge of the Supreme Court – responded to the announcement with: “I don’t believe that.”

The old wooden courthouse building had been blown up, struck by a cyclone, riddled with holes in the floor, and eventually burnt down. Shockingly, it had no air-conditioning. Judge Finn, then a prosecutor, owned what was thought to be the oldest wig in Australia, held together with glue. He refused to buy a new one, insisting the government should provide the tools of his trade. When a visiting Brisbane judge kept his wig on in court, Finn was forced to follow suit. As the heat rose, the wig melted. Glue slid down his face, and the remains fused to his head.

The old courthouse, 1962

The current Townsville Courthouse is a remarkable structure, influenced by the Japanese Metabolism movement. Coral-inspired facings reflect the local reef. Designed by Ray Smith[2], of Hall, Phillips & Wilson, it won the National Enduring Architecture Award in 2018. The interior was purpose-built with significant input from Justice Skerman, another former Northern Judge. It harbours forward-thinking design: bar tables angled to provide equal access to judge and jury; and a female robing room – small, yet generously fitted with lockers.

Today, the building houses the Magistrates, District and Supreme Courts, together with QCAT and the Land Court. And, on occasion, it receives filings from sovereign citizens – though, true to form, they often “don’t believe that” either.

Supreme Court One is a majestic courtroom, designed to dispense justice in the most solemn of cases. High ceilings, an interior balcony, and an entire wall of square windows connect participants to the vast North Queensland sky, a reminder that life is bigger than the moments inside. It has been the centre of hundreds of murder trials, the gallery often peopled with family and friends – lost sons and daughters invisible, yet never forgotten.

On 24 October 2025, Court One hosted the fiftieth anniversary ceremony, attended by a who’s who of the local legal profession, the judiciary, and the Attorney-General. Yet back in 1993, that same courtroom was occupied by a twenty-year-old woman watching the trial for the murder of her twin brother. Two flatmates, Cowburn and Fulford, accused of bludgeoning him to death with a rock as he slept. Those moments have faded for most, except the families and friends, and every person involved in that trial. The jurors had two weeks to hear the case, two days to deliberate and return a verdict of manslaughter – not murder – and a lifetime to doubt their decision. Thirty years on, her name, like so many others, remains unspoken.

On the balconies beyond the windows, cigarettes have been smoked and secrets shared. Deals negotiated. Affairs begun and ended amidst the blaze of fifteen-hour workdays. Grief, heartbreak and triumph. Grand characters have graced its interiors[3]. Mark ‘Sludge’ Donnelly, of the Townsville Bar from the 1980s to the 2000s. He fired legal arguments at the bench, his throat a powerful machine gun of logic. He once bought an entire jury a beer after they acquitted his client. Sludge, a central figure in the ‘raspberry fuzzberry’ scandal – drinking the cocktail bought for him at the Exchange Hotel by a juror, this incident later emerging in the evidence at a subsequent retrial.

Courtroom One is the second home of barrister Harvey Walters. Trusted and reliable. Prominent in so many major murder trials: MacQueen and Peel, Farr Scrivener and Hills. His address in the Rachael Antonio case has become the stuff of legends. No body had been found: Walters told the jury they could not even be satisfied she was dead. At that moment, a woman with a stunning resemblance to Rachael entered the gallery. A collective gasp. Could it be? She sat quietly – a work experience student. Not Rachael, but the point had been made.

Many competent prosecutors have worked Courtroom One: David “Moggy” Meredith, James “Jim” Henry SC (now Justice Henry), Justin Greggery KC and others. Competent, diligent prosecutors. Patiently guiding juries to the truth, through the maze of misdirection strewn by the colourful cast of defence lawyers.

The Townsville courtrooms have witnessed every kind of drama: the competent lawyer, the reckless lawyer, the acquittal, the high-stakes case. It has been a theatre of human experience, a thrill ride more intense than any film. A small stage, yet vast in its impact.

Judges’ associates, often fresh from James Cook University, are thrust into the intensity of Townsville courtroom trials, riding every emotional wave. One associate, tasked with reading lengthy transcripts to the jury late at night, unconsciously adopted the accents and mannerisms of the colourful barristers she was quoting, amusing the courtroom while keeping the jury informed in the prerecording days, when stenographers typed every word.

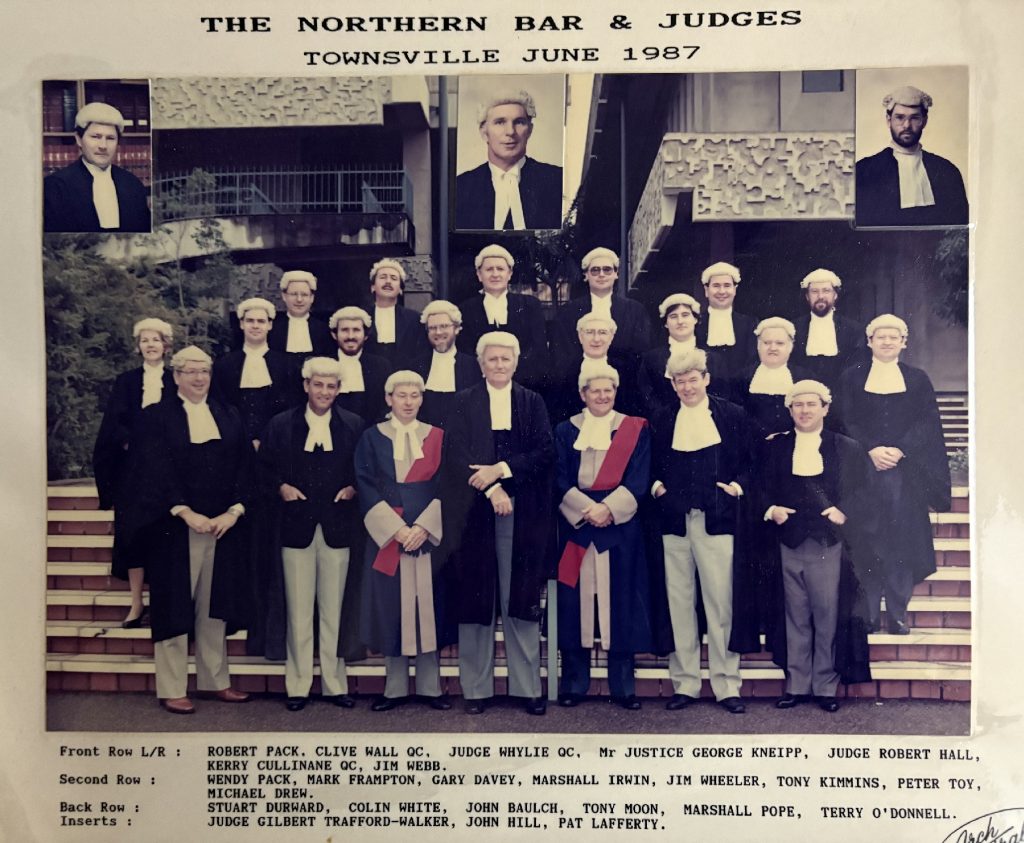

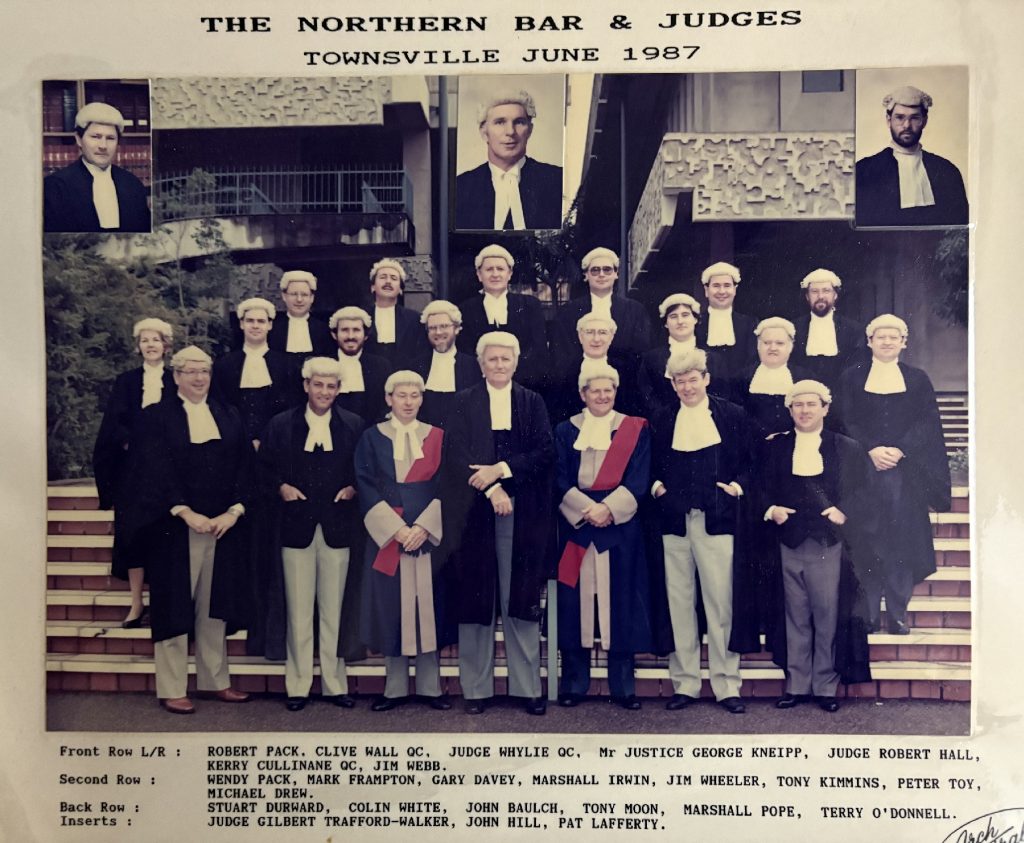

Civil trials are still run in Townsville – medical negligence, workplace injuries, wills and commercial disputes. Specialist lawyers have their own colour: Michael “Swampy” Drew for plaintiffs, wily and strategic; stern insurance representatives frowning as cases turn unexpectedly; and silks such as John Baulch and Stuart Durward, were stalwart in every crisis. The Northern Bar has always been regarded as particularly strong.

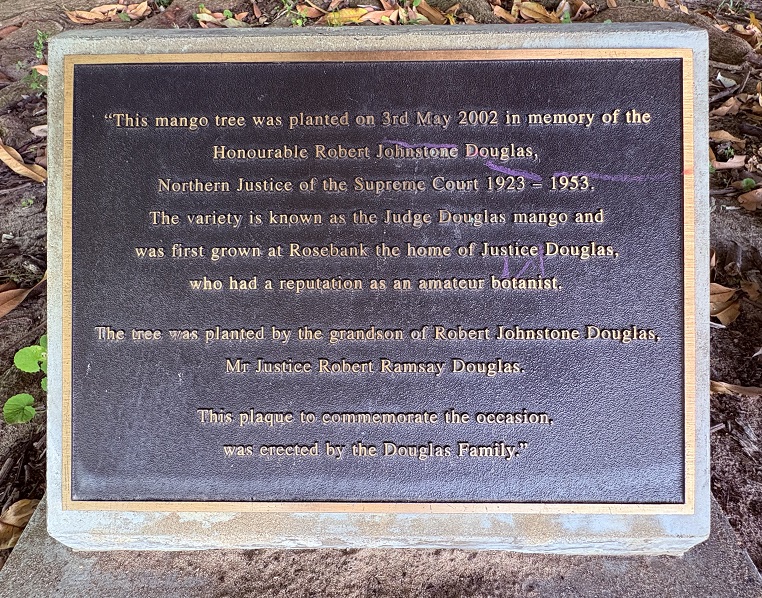

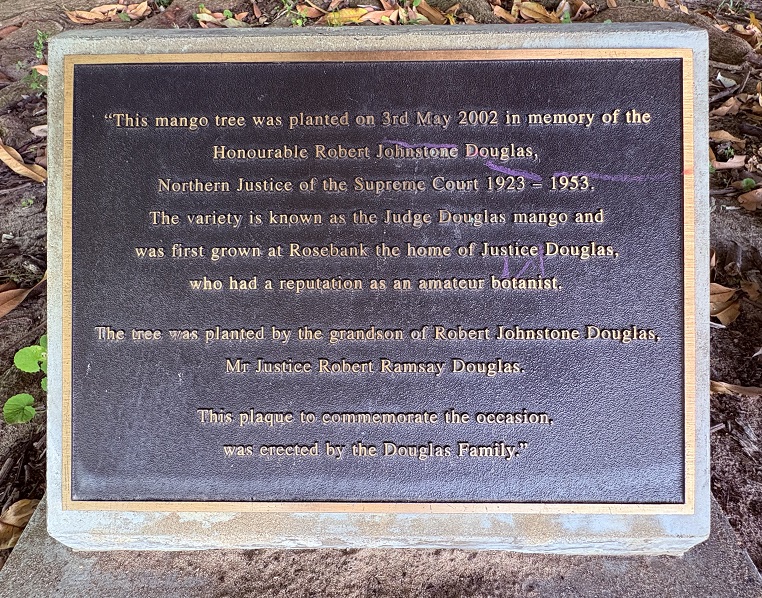

Kerry and Bob planting the RJ Douglas mango tree

Many Judges have come and gone over the last fifty years. The mango tree out the front of the courthouse was planted by then Justices K.A. ‘Kerry’ Cullinane and Robert ‘Bob’ Douglas. The tree itself is a genus created by Justice R.J. Douglas, again, Northern Judge for over forty years and a keen botanist. Cullinane purchased it at market, where it was advertised as the “Judge R.J. Douglas” tree. It bears little fruit but, as Cullinane notes, stands where the innocent and guilty pass equally.

Portraits in Courtroom One capture Justices Cullinane and Sir George Kneipp, successive Northern Judges, dignified in oil as they were on the bench. Kneipp never wore a wig and is famous for his capacity for beer, often consumed at the public bar. He suffered personal tragedy, but continued working with quiet determination – he and Lady Ada lost their daughter, Christine, to an incident at the waterhole in Arcadia Bay on Magnetic Island at Easter in 1966. He passed away soon after his retirement. His ghost is said to haunt the judges’ chambers on Level D. When told about this, Lady Ada said: “That’d be right, if the blighter ever came back, he’d go straight to work.”

Justice Cullinane. What more can you say about a man than that he is a hero to his associates, and loved by his wife and children. Registry staff compiled a history of the Judge when he retired, and on the front they stated: “Kerry, the kind and considerate.”

Judges’ Chambers behind the courtrooms on Levels C and D have a sense of space—wide corridors, rectangular windows evenly spaced for light, and anterooms where associates can gossip while preserving the balance of privacy and access. From Chambers, the view stretches over the legal mean streets below.

One afternoon, Justice Cullinane asked his associate to call a solicitor, who was late. They stood quietly, side by side, watching a suited figure charge down Walker Street—jacket billowing, briefcase flapping. He tripped, suspended in air, arms and legs flailing, then catlike found his feet. By the time he reached court, the Judge simply nodded. No need for apology.

Over the years, eminent Judges have filled the Chambers on Level C. Among them was Judge Kerry O’Brien, a former prosecutor who was to be appointed Chief Judge of the District Court – a fair Judge who enjoyed Bar dinners and the occasional sing-along. Judge Pack QC, an icon at the bar and then the bench, with his keen intellect, low booming voice, understanding of life out West, and zero tolerance for dangerous drivers.

Then there was Judge Clive Wall QC (now KC), formerly of the local Bar, who brought his unique flair to the bench. A straight shooter with a penchant for sharp wit, he lunched in style, wore short-sleeve business shirts from Best and Less, and played a fierce game of lawn bowls. He had little patience for fools or cowards, and in Court, he led from the hip.

Northern bar and Judges 1987

Some lawyers viewed an appearance before Judge Wall as a walk in the lion’s den. But the better ones saw an opportunity. His directness laid out every concern, giving them the chance to address each point – and, with enough skill, steer him—sometimes reluctantly, metaphorically kicking and screaming – towards the outcome they sought.

Then there’s Judge Greg Lynham, graduate of James Cook University, who was a popular President of the JCU Law Students’ Society[4]. He is a former train driver, and an Anglican Priest, which perhaps explains his unflappable nature. He practised at the Townsville Bar before his appointment to the Bench, where he continues to keep proceedings on track.

The District Court in Townsville has seen its share of complex and often harrowing cases over the last fifty years. A paedophile ring uncovered in an otherwise quiet suburb—an unimaginable honey trap that lured vulnerable foster children into drugs and exploitation. And the soldier thirty years ago who smashed his twin babies heads together, leaving both brain-damaged. Convicted of grievous bodily harm, his sentence has long been served. But those babies, now adults, and their mother, are still serving theirs.

This is the grim reality of life in the Townsville Courthouse. We cannot turn back time and undo the damage. We do not fix things. Our justice system has no magic wand, much as we might wish. What we can offer is a steadfast commitment to the rule of law, a fair hearing, and just consequences in accordance with the rule of law.

But even as we uphold these principles, gaps remain. Fifty years ago, Justice Skerman ensured fair provision of services for women lawyers in the Court. Yet, despite these efforts, no woman has ever been appointed as a sitting Judge in Townsville.

Across the landing from the District Court, the Magistrates’ Courts on Level B plays a critical role in the Townsville justice system. While their connection to the broader judicial landscape is less visible, magistrates hear ninety-five percent of all cases in Townsville[5].

Level B is where the full circle of criminal life unfolds. Like Rumpole of the Bailey – who knew the Timmins family better than they knew themselves – magistrates often come to know local families intimately. Newborns enter the child protection system – some with foetal alcohol syndrome, others abandoned in shopping centres or forgotten in showers. Their parents, weighed down by drug or alcohol addictions, repeatedly appear in magistrates’ courts – for tenancy disputes, theft, drugs, domestic violence, and complaints about vicious dogs.

As the children grow, their offences escalate – shoplifting, break-ins, stolen cars. Occasionally, later comes robbery, rape, or murder. Time in jail often morphs the offending into domestic violence and public drunkenness. Eventually, these offenders wear out, winding down with public nuisance charges on Level B before fading from the system altogether, far older than their years.

One of the first trials I observed as associate to Justice Cullinane involved a 17-year-old indigenous teenager from Palm Island, charged with murder. He shot someone in the street, accusing the dead man of being a paedophile. I never really knew if the accusation was true. He was convicted of manslaughter and served a seven-year sentence.

Twenty-five years later, I sat as a Magistrate in the same courthouse – except now, two floors lower. The teenager, now fully grown, appeared on videolink from the same prison where he had served his sentence. His criminal record had evolved, now including multiple convictions for paedophilia. His life is a stark reminder of the circle of crime that repeats itself through the generations.

And it begs the question: in the decades to come, how many of his victims will walk through these same old courthouse doors, and embark on a similar journey?

It is not just lawyers who’ve given their best to this Courthouse. Volunteers like Salvation Army Officer Bob Downs – now in his nineties – have been at the front desk for more than forty-five years. Anne Frankcom, whose portrait hangs on the front desk, supported domestic violence victims from the early 1990s – long before government services were available.

On the landing between courts, security guards work hard to keep everyone safe – scanning, searching, checking. But for most of the courthouse’s history, that landing was a different place. There were no checks. Security used to be a retirement job, with elderly guards passing the time doing crosswords. Occasionally, someone would be reprimanded for leaving a cigarette butt on the walkway. Once, a man snatched a gun from a police officer in the magistrates’ court and escaped, waving it around in the foyer before bolting. We talked about it for weeks. We didn’t want more security, just fewer guns. Defendants would wander in and out, dressed in their finest. Now, you’re lucky to get a collared shirt. The courthouse has evolved with society.

The District and Supreme Court Registry in Townsville has been a centre of excellence for fifty years. Competent, polite, and efficient, the staff have seen it all—article clerks dashing in with documents that needed filing yesterday, assisting the Registrar to collar jurors on the street when there weren’t enough to fill the panel, serving legal process to people on ships. Long-serving members like Phil Green – who has worked there for forty-five years – Rita Green, Katina Argyros, Robin Wegener, Lisa Dyke, and Angela Blackford have been the backbone of this operation.

Jenny Dawson, who cleaned the courts for over forty years, was a quiet presence until she retired.

1992

Brian Hooper, the Supreme Court bailiff for many years, was exemplary – only once did a juror escape on his watch. The jury were seconded at the Sugar Shaker. After midnight, one juror was spotted by police in The Bank nightclub. The juror bolted back to the hotel and ran around the jury floor (an unbroken circle), trying to evade police. Brian sat still and got his man, but it was an expensive night for the government – they had to fund a retrial.

On the magistrates’ registry side, the workload is relentless. Staff come and go like the rolling tide, but there are the stayers who have kept the place afloat over the last fifty years – Kerry Christopher, Judy Stagg, Hilda Wilson, Debra Shibasaki, Ellen Brown, Graeme Evans, Brendan Moule, Susie Warrington (now magistrate).

On the ground floor, bailiff Ian Kennedy has been on duty for thirty-seven years. Once with his own office, now his desk is under his hat on the first floor. His unflappable nature and amused smile are his best tools of enforcement. When he says the court process has been served, you can rely on him.

Beneath the courthouse, in the cells, police, inmates, Salvation Army chaplains, lawyers, and nurses work tirelessly with the never-ending surge of prisoners. Over the past fifty years, watchhouse keepers have played a vital role in ensuring safety and order, overseeing the flow of detainees – from meth addicts in withdrawal to children after crime sprees.

This article is a snapshot of life in the Townsville Courts over the past fifty years. Many people have been mentioned, but countless others who should have been mentioned have shared the best days of their lives, imparting their knowledge, time and ability with the community of Townsville – barristers, solicitors, magistrates and judges, clerks, security, support staff, cleaners, police, and volunteers – making the Townsville courthouse a place where justice, on balance, has prevailed.

No system is flawless – to err is human. But if the role of a court is to apply the law impartially, free from fear or favour, affection or ill will, then those who envisioned and built the Townsville Courthouse would take pride in its first fifty years.

The RJ Douglas mango tree today

[1] Lord Nicholls, White v White [2000] UKHL 54netny

[2] after attending the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka

[3] Colourful personalities fill the Courtrooms with enchantment.

[4] At the same time I was Editor of the JCU Student Law Society Journal, The Precedent.

[5] https://www.courts.qld.gov.au/courts/magistrates-court/about-the-magistrates-court

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY SPEECH – 8 MARCH 2023.HOSTED BY THE FNQLA, AT THE PULLMAN INTERNATIONAL, CAIRNS.

Introduction by the Honourable Justice Helen Bowskill, Chief Justice of Queensland:

Good morning everyone. I join in acknowledging the Gimuy Walubara Yidinji people, the first owners and custodians of the land and waters in and around Cairns, and pay my respects to their elders, those who have looked after and spoken for these lands and waters in the past and who do so today.

This year, on International Women’s Day, we are invited to embrace equity – to imagine a gender equal world. A world free of bias, stereotypes, and discrimination. A world that’s diverse, equitable, and inclusive. A world where difference is valued and celebrated. That is an empowering message not limited to women, but extending to all within our community.

It is a great pleasure to be with you here in Cairns to celebrate this day. And also my great pleasure to introduce to you the guest speaker for this morning’s event, Magistrate Cathy McLennan.

Her Honour has embraced equity throughout her impressive professional career. Magistrate McLennan was admitted to the Bar in 1994, at the very young age of 22 – the youngest barrister in Queensland at the time. She first worked as a barrister for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service in Townsville and Palm Island, going on to write an award-winning book ‘Saltwater’ detailing her experiences in that role. She went on to practice at the private Bar for many years, before being appointed as a Magistrate in 2015.

In addition to her work as a barrister, Magistrate McLennan has been a tutor at James Cook University – where she is proudly lauded as the first JCU graduate to be appointed a judicial officer – a director on the Board of the Townsville Community Legal Service, and a mentor through Queensland Women Lawyers.

Would you please join me in warmly welcoming Magistrate McLennan to the stage.

Her Honour’s Speech:

In preparation for my speech, I asked my ten-year-old niece, Asha, what I should say. She said I should be the light of the world – and don’t stuff it up. And if you stuff it up, it’s all down to you, Aunty Cathy. And I was thinking about that, and how that’s the beauty of being a woman today. We have the chance to achieve what we want in this world, and we can do great things, or stuff them up. The choice and the opportunities are ours.

We have so many incredible women in Queensland. I am humbled and delighted to be here with you, to celebrate International Women’s Day, because I am the living embodiment of the achievements of women. I am literally standing here alive today, because of the excellent skill, ability, talent, and compassion of female doctors and nurses. Three years ago, I was diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer. My surgeon, Dr Angela Robson, had the skill to extract the tumour from a difficult position, and obtain two-millimetre margins. Which was a big deal. My female vascular surgeon, Dr Roxanne Wu, had the skills to insert and remove a chemotherapy port into a major vein in my neck and chest. My oncologist, Dr Megan Lyle, stopped the spread of cancer cells. And the army of women oncology nurses, social workers, radiologists, psychologists, receptionists and administrators. All working tirelessly to help save my life through the worst of the COVID lockdowns. Somehow, invisibly managing their own families, the risks of infection, kids, home-schooling, and their private lives in the background.

I trusted those women. I really trusted them with my life. Their compassion and practicality helped me feel my life was important, and that I could leave them to their jobs and get on with mine, which was to stay as healthy as I could. So today, International Women’s Day, I celebrate you. Women in medicine have added enormous positives to the benefit of society. The world is a better place with women like this.

Women in law have the same impact on the world and their clients. I see every day before me in court, female lawyers performing their roles with skill, intelligence, practicality, patience, and compassion. I want to acknowledge you all today. I hope you know that in part, this day is about celebrating each and every one of you and your achievements. You have all overcome hardship and adversity, and you are paving a pathway for girls, like my little niece Asha, to believe that for them, anything is possible.

I had a lot of time during my illness to reflect on my own life, where I’ve come from and where I’ve gone. Flat on my back in a darkened room, unable even to listen to podcasts. Reflecting on my life, all the things I’ve fought through. And whether it was worth it. Because there are missing sentences in between the awards and accolades in my CV. There is struggle. There is suffering. Just the same as many of you sitting there. Because that’s a real life. Agatha Christie wrote a book called Absent in the Spring about something like this. She later said she was always fascinated by what you would discover about yourself, if forced to spend that much time alone with your own mind. One of the things I reflected on, was what I went through as a young lawyer.

“I was so proud of myself in my new suit, with my barristers robes slung over my arm. Until some barristers got into the lift, congratulated the men I was with, and asked me if I was a shopgirl from Myer.”

Thirty years ago, when I was admitted as a barrister in Townsville, women did not have the opportunities we have today. Things were a lot different then. We should never forget how far and how fast we’ve come.

In a wider context, when I was growing up and at the point of entering law, women had it tough. A level of domestic violence, short of serious bodily injury, was acceptable. Absolutely not in my home, I have a wonderful father. But in a wider context, there were no domestic violence laws. Married women were effectively the property of their husbands. Thirty years ago, it was not an offence for a husband to rape his wife. The Queensland Criminal Code specifically excluded husbands from the definition of rape, and it was only in 1991, in the case of R v L[1], that the High Court finally decided that a man no longer had the right to rape his wife.

In August 1992, about three months before I started my first job in law, there was a case in South Australia that highlights the wider attitudes toward women at the time. Justice Derek Bollen told a jury, in a case involving a defendant charged with five counts of raping his wife, that it was acceptable for men to use rough handling on their wives. He stated in his address to the jury, and I quote[2]:

“There is, of course, nothing wrong with a husband, faced with his wife’s initial refusal to engage in intercourse, in attempting, in an acceptable way, to persuade her to change her mind, and that may involve a measure of rougher than usual handling.”

In the furore that followed, I think the most accurate comment was made by Eva Cox, of the Women’s Electoral Lobby, who said[3]: “The interesting thing is that he actually said it. I have a terrible suspicion that there is no lack of judges that also think it.” Indeed, when this case came to the Court of Criminal Appeal, Justice Kevin Duggan noted that most difficulties with Justice Bollen’s remarks as a statement of law would have ‘evaporated’ if Justice Bollen had added the words ‘acceptable to the wife’ in his direction to the jury[4]. Senator Gareth Evans, speaking in Parliament about that time, is quoted in Hansard as stating[5]: “…if rape is inevitable, one might as well, if not enjoy it, at least succumb with such grace as one can muster in the circumstances.” And into this mix of course, who could forget the Judge who stated[6]: “No doesn’t always mean no.” It was the same around the world. That year, one of the defences to Mike Tyson’s rape charge, that they obviously expected the jury to accept, was that as Tyson was renowned for being a rough and brutal man, women who came near him could reasonably be expected to have consented to this level of roughness[7].

In 1993, academic Helen Pringle wrote in the Griffith Law Review that[8]:

“Many of us are accustomed to such levels of intimate brutality that many cases of domestic violence go unremarked as well as unreported. This idea (that violence to women is acceptable) rests on a commonplace fantasy, a fantasy that women and their bodies are there for the expression of men’s needs. And judges and the law have played a decisive part in the construction of this fantasy.”

As shocking as those cases were, this was the point that things began to change. Women, such as myself, began emerging from universities and fighting for our places in law. Right at that point I would describe it as a boiling pot, a tug of war in my own little cosmos in Townsville, on one side sexism and fear, bastions of men and women frightened by the societal changes they were seeing, with the women beginning to assert themselves and emerge within the ranks of the professions. While on the other side, there were men and women who were ardently fighting for the cause of women, willing to provide support, and safe quarters to women like myself.

“There certainly was and is misogyny in the legal profession, but at the same time, there are wonderful men and women, willing to support younger women coming up through the ranks”

But I only know all this really, in hindsight. Upon reflection, it explains the struggles and difficulties I faced. At the time, I was a young, idealistic, 22-year-old barrister. And naïve, incredibly naïve, about the sexism and misogyny that existed at the time. It never occurred to me that anyone would think that women were not as smart, if not smarter than men.

I grew up in a strong family unit, my mother, my father and sister. Both my parents were excellent role models. My father was always respectful and encouraging. I’ve since read that a really good male role model is essential to giving girls a sense of identity and confidence growing up. If that’s true my father has a lot to answer for, because I was probably way over-confident as a young lawyer.

Growing up, my parents always relied on me to work little jobs in their business, Dandaloo holiday units on Magnetic Island. One of my jobs was to turn on the coloured lights around the guest BBQ area and pool in the evenings. I made one cent a day, turning them on in the five minutes between The Goodies and Doctor Who. And my father, an accountant, had a ledger where he entered the one cents in a long column. And they added up, over time. One-hundred cents. Two-hundred cents. But, by cleaning the toilets, I got two hundred cents in a single day! Great introduction to money making and to life. Step one, study hard and get a career. There’s no money in toilets.

I never had a sense while growing up of being any less capable than my male counterparts, because I was female. I now know that view existed. But I was encouraged for the abilities I had. At high school, I was fortunate to attend The Cathedral School in Townsville, which is still an excellent school. My year was the first year they admitted boys. They were all in my class, but for some reason they were never in competition for the top academic spots. So I grew up in an atmosphere of women being expected to do well. I studied law at James Cook University with the incredible, Professor Marylyn Mayo – a strong role model for JCU law students. I was taught evidence by Marjorie Pagani, an intelligent, capable barrister and lecturer we all respected. So when I first started working in law, I was still very naïve. The overt comments men had made to me, at least a dozen times, about my being a woman and so not capable of practicing law, I had taken as evidence of their own stupidity.

“But the thing that I’ve learned over the years is, as nice as my husband is, I have to be my own handsome prince”

This constant subtle discouragement did become a constant theme in my first five years at the Bar. When I finished the Bar Practice course in Brisbane, the two senior barristers who had mentored us took us to the Majestic Hotel for celebration drinks. It was a nudie bar. Beer and boobs. It was an attempt to put us in our place, because it was way too uncomfortable to ever be anything else – but I can tell you this, of the three women there that day, one is now a magistrate, one a Supreme Court Justice, and one a very senior prosecutor.

So, about two weeks later, I was admitted as a barrister. On the day of my admission, I was in the lift of the Inns of Court with male friends. I was so proud of myself in my new suit, with my barristers robes slung over my arm. Until some barristers got into the lift, congratulated the men I was with, and asked me if I was a shopgirl from Myer.

I guess the first major thing that got through to me, though, was about two weeks later when the Queen’s Counsel who was my mentor told me I couldn’t possibly succeed at the Bar because I was a woman. I’d rung him one evening to ask a question about the trial I had the next day. He said, and I vividly remember this: “You’re a woman. You’ll never succeed.” Then he hung up on me. And my reaction was just complete shock. How on earth could someone that thick become a QC?

So, I just ran the trial the next day without his help. And I won the trial, so, I’d say persistence pays off.

There were a lot of other little issues that interfered with my ability to do my job. The male lawyers in Townsville would all meet at the North Queensland Club, the only all male club in NQ. So I couldn’t get in to be part of the meetings about cases, unless it was a special event and there was a man willing to sign me in. Also, as a really young woman, I was 22 at the time and single, there was a lot of innuendo. Made up rumours. One day, I wore slacks into the District Court and a visiting Judge acted like I was invisible when I tried to appear during the callover. I’ll tell you, it’s a very strange experience to stand at the bar table in the District Court, and have a judge literally pretend you’re not there. I said, ‘Good morning Your Honour, Cathy McLennan, barrister, instructed by X, I appear for the defendant.’ And he looked through me, and he looked around the court over his bifocals, and he said, ‘Oh, is anyone going to appear for the defendant in this matter?’ And I said, ‘Yes Judge. I am.’

“It was only in 1991, in the case of R v L, that the High Court finally decided that a man no longer had the right to rape his wife.”

And I knew what was wrong, someone had told me when I arrived that he wouldn’t recognise me if I wore slacks and not a skirt. And he’s still peering around the court, and I start waving, ‘Your Honour? I’m over here!” Nothing. Anyway, finally another barrister stepped up next to me and I told him when I wanted the matter listed and he listed the case.

Although to be fair, I should point out that it ran both ways. Men were not allowed to wear skirts.

One of the other things that happened about that time, that really sticks out in my mind, was my first jury trial. I was 24 and had been practicing for two years in the Magistrate’s Court, reading new legislation and cases every night, so I felt prepared in terms of the law, and I had done some amateur theatre, to prepare for speaking in front of juries. Finally, it happened. I got flicked my first brief for a jury trial at nine o’clock at night. It was an assault, and it was set for hearing at 10am the next day. The material I got didn’t include copies of exhibits and the next morning I couldn’t get them from the prosecutor. I applied for an adjournment of the case, and the Judge said, ‘Oh absolutely, you can have an adjournment to prepare.’ And he gave me one hour. When the case started, I still didn’t have copies of exhibits, and when the prosecutor started tendering them, I was motioning for the bailiff to show them to me. The judge started making comments like, ‘Oh don’t put your hand up now, Ms McLennan, you’re not in a school room now.’ And I’d make an objection and he’d refuse to hear me, and I’d try to question witnesses and he’d stop my questions, and tell me to sit down.

So of course, that evening, I went back to chambers, and really thought about it. I decided we didn’t have much of a defence anyway, so the trick was for me to keep standing up and trying to speak in court, and to let the Judge keep shouting me down. Reasonable doubt, that’s all you need to establish. And if the Judge kept shouting me down, how could the jury convict beyond reasonable doubt if I looked like I had a great defence, but never got a chance to speak? The Judge didn’t realise what I was doing until the end. By then it was too late. Not guilty.

But, while those things were happening in the background of my career, I’ve always been a really positive thinker, and I gained so much encouragement from all the support I received. One of the things that surprised me was all the support I had from my university contemporaries. I went through James Cook University with some intelligent women I liked and admired. There were a few who were briefing me. I was grateful both on a financial and emotional level for that support. I’ve always thought how important it is for women to support women.

Plus, I felt fortunate to have been able to study law and be a barrister. If I had been ten years older, I would not have had that opportunity in a small town like Townsville. The fact that I was the only female at the time doing criminal law, reinforced in me a feeling of how lucky I was to have each and every case. And I really enjoyed the work. I can be persuasive. And it’s a pleasure to be able to work at something you’re good at. Jury trials are nerve-wracking but exciting.

One thing I do get asked a bit is, what was your worst case? I defended several murders. But probably the very worst case I had as a barrister was when I defended a series of paedophiles. I won’t go into it, it’s awful. My sister suggested I entirely delete this part from my talk, but I’ve just deleted some of the disturbing details. What happened was that I worked hard on those cases and all those defendants were acquitted. I now have sons, and I have to live with being the barrister who had those men acquitted. The way I live with it is that I was always honest. I never lied, I never did anything that was outside the law, or unethical. I did my job as best as I could for my clients, inside the boundary of what I was ethically able to do. That’s how you can live with being a defence lawyer and doing the difficult cases. But it still haunts me sometimes.

“It never occurred to me that anyone would think that women were not as smart, if not smarter than men.”

It’s been so exciting during my lifetime, to see one by one the barriers being broken down. The things that you think may not be possible for women, being made possible, and happening, because of the determination and perseverance of women who never take no for an answer. These days, law graduates are at least half women. Now, I really think that girls can do anything. We can win the Melbourne Cup. We can be businesswomen, magistrates, we can be police officers, army officers, or we can end up in jail. Play AFL or Rugby. But we get to make choices for our own lives that lead to where we want to go. There certainly was and is misogyny in the legal profession, but at the same time, there are wonderful men and women, willing to support younger women coming up through the ranks. I’ve tried to show in this talk, what I went through, because it’s vital to remember where we’ve come from, so we never risk losing our hard-fought success. The reality is, we are so fortunate to have these amazing opportunities because of the strength and determination of the women that came before us. We can write books, be marine biologists. It’s a matter of making our decisions as to what we choose to do and putting in the time and effort to do it well.

There are so many women who suffered to give us these opportunities. Generations of everyday women who have paved the path of equality smooth, by walking on the rough stones of progress with their bare feet, the stones becoming smoother as each of us treads the path. We always hear talk of the sacrifices of the suffragettes, marching and protesting and leaping in front of the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby. But a big part of the opportunities we have today were won by those quiet women who had been downtrodden all their lives, taught to expect little of themselves and their own value, who stepped up in World War 1, into the jobs men previously had, and they did those jobs well. In factories, in law, in the police force, in hospitals, schools and industries all over the world. And they kept the countries running, in times of great hardship, and they did it well. And then again in World War 2, quietly but immediately stepped into those roles. And gained the respect that got us to where we are today. Not by shouting, but by leading by example. Quietly forging the path, following their dreams. Much like most of us here today. We do our jobs to the best of our ability every day. Sometimes that is enough. Because that means it is normal for women to have successful careers, and that empowers children like my niece Asha, to have the opportunity to do anything she wants. She can be Princess Fairytale and raise babies. Or she can go out and cure cancer. Or she can stuff it all up.

But, in saying all this, anyone who works in criminal law knows there are two worlds. There’s the world where most of us here inhabit. Where women do have these opportunities. And then there’s the other world, where women are bashed from a young age, sexually abused, and grow up without hope. When I was growing up, I remember seeing a woman bashed in the Townsville mall, and everyone going about their business, ignoring it. And of course, as a lawyer and now magistrate, I see it every day. But there are amazing societal changes going on in the field of domestic violence. The other day I watched the most incredible CCTV footage – an aboriginal woman was being beaten with a metal chair at a shopping centre and you should have seen the female shoppers converge! Old and young, they ran at that man, defended that aboriginal woman with everything they had, one woman, had a walker, she was banging it on the ground, another woman was throwing bits of paper and someone else donged him with her shopping bags. Ordinary women standing up for one beaten woman. I love that I’m now living in that world, where ordinary women have the courage to stand between an armed man and his partner.

I’m very fortunate to be here. Not just career wise, but I’m proud of my family, my kids. I’ve been grateful to have the opportunity to be a mother and a lawyer. I have identical twin boys, and they’re 17. And I see how much they’re living the fairytale, young love. But the thing that I’ve learned over the years is, as nice as my husband is, I have to be my own handsome prince. And I have to be the one that does the rescuing in times of crisis. That’s not to say that my boys are not strong, resilient handsome prince types. And yes, I might be biased, but they are strong men because they’ve been through an awful lot in their life. I’m lucky to have had wonderful female doctors and my strong mother and I’m lucky to have had the resilience to fight cancer and keep going. I think it’s only through trouble that we really learn, and we get stronger and more understanding and more compassionate as human beings. Helen Reddy said it best, yes, I am wise, but it’s wisdom born of pain. But I’ve got to the point in my life where it’s enough. I don’t want to be wiser. I don’t want to be stronger. But there will be more downs in my life, and more ups, and I also know that whatever comes, I’ll cope.

[1] R v L (1991) 174 CLR 379

[2] R v David Norman Johns, unreported, Supreme Court of South Australia, transcript of summing up to the jury by Bollen J, 26 August 1992, p.13. This was no idle error of terminology, Justice Bollen went on with similar comments such as at page 14: “It seems to me that a wife always had the right to say no although, if she persisted in doing that unreasonably, it might be, in the old family law, thought to be something unreasonable.”

[3] Judge’s rape tales infuriate Australian women by Robert Milliken. Published in the Independent Newspaper, Thursday 14 January 1993.

[4] Pringle, Helen. “Acting Like a Man: Seduction and Rape in the Law” (1993) 2(1) Griffith Law Review 64.

[5] Hansard (Senate), 24 February 1987, p 514.

[6] Justice Raymond Dean, Old Bailey, April 1990, Transcript Address to jury page 34 lines 24-30: “As the gentlemen on the jury will understand, when a woman says no she doesn’t always mean it. Men can’t turn their emotions on and off like a tap like some women can.” See Tempkins, J, Rape and the Legal Process, Volume 2, December 2022, Oxford Academic, page 4, Chapter 1, Rape, Rape Victims, and the Criminal Justice System.

[7] Pringle, Helen. “Acting Like a Man: Seduction and Rape in the Law” (1993) 2(1) Griffith Law Review 72.

[8] IBID at page 73.

The new courthouse, 1975

The new courthouse, 1975

The old courthouse, 1962

The old courthouse, 1962

Kerry and Bob planting the RJ Douglas mango tree

Kerry and Bob planting the RJ Douglas mango tree

Northern bar and Judges 1987

Northern bar and Judges 1987

1992

1992

The RJ Douglas mango tree today

The RJ Douglas mango tree today