When is conduct ‘unconscionable’? A norm by reference to ‘conscience’? Mercedes distributors complained about the term of their franchise agreements in AHG WA (2015) Pty Ltd v Mercedes-Benz Australia/Pacific Pty Ltd [2025] FCAFC 86 (9 July 2025). Given the stakes involved, surely a case heading to the Supreme Tribunal? Moshinksy, Bromwich and Anderson JJ – in respect of ss 21 and 22 of the Australian Consumer Law (Cth) – wrote:

…

The appellants’ submissions

[115] In oral submissions, senior counsel for the appellants said that the appellants’ central submission is that his Honour did not apply the correct principles to the question of unconscionable conduct, namely those stated by the High Court in Productivity Partners [Pty Ltd (trading as “Captain Cook College”) v ACCC [2024] HCA 27; 419 ALR 30].

[116] Senior counsel submitted that the essential holding of the High Court was that the court must evaluate the impugned conduct against a normative standard of conscience which is permeated with accepted and acceptable community standards to determine whether s 21 has been contravened.

[117] Senior counsel submitted that there were three key aspects of the High Court’s reasons in Productivity Partners:

(a) First, the proper judicial method for assessing statutory unconscionable conduct is to conduct an evaluative assessment of impugned conduct against the standard he had referred to. Senior counsel relied on Productivity Partners at [50]–[64] per Gageler CJ and Jagot J (especially at [60]) (Gleeson J agreeing at [310], Beech-Jones J agreeing at [340]). Senior counsel also relied on [282] per Steward J.

(b) The second aspect of judicial method is that set out in Paccioco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2015] FCAFC 50; 236 FCR 199 (Paccioco) at [263]–[299] per Allsop CJ The norms and values demanded in one case may be different from those in another, to cover broad and evolving practices in different sectors of the business community. These norms and values include certainty in commercial transactions, honesty, the absence of trickery or sharp practice, fairness when dealing with customers, the faithful performance of bargains and promises freely made and the protection of the vulnerable. Critically, opportunistic conduct is conduct which the courts have identified as potentially offending those norms and values. Senior counsel submitted that various members of the High Court in Productivity Partners adopted the reasons of Allsop CJ in Paccioco: see Productivity Partners at [100] and [105] per Gordon J, [284] per Steward J, [314] per Gleeson J, [340] per Beech-Jones J.

(c) The third aspect is that the matters listed in s 22 of the Australian Consumer Law embody in a non-exhaustive way statutory values and norms which may indicate that conduct was unconscionable. Section 22 provides a frame of reference for identifying the values expressed under the statute which, in turn, informs whether conduct or a course of conduct is unconscionable within the meaning of s 21. Section 22 does not act as statutory criteria that determine the metes and bounds within which the normative standard prescribed by s 21 is to be applied. Senior counsel relied on Productivity Partners at [100]–[105] per Gordon J (Steward J agreeing at [282], Gleeson J agreeing at [314], Beech-Jones J agreeing at [340]).

[118] Senior counsel submitted that Gordon J’s approach was “completely contrary” to the approach taken by the primary judge in the present case. Senior counsel submitted that the primary judge’s reasoning, particularly at J[3506], demonstrated error. Senior counsel submitted:

Far from being intellectual fairy floss, the search for accepted and acceptable social and community standards is the central task to the court’s role in seeking to identify whether the conduct was unconscionable. The trial judge erred in holding to the contrary and that necessarily truncated his analysis of the circumstances.

(emphasis added)

[119] Later in oral submissions, senior counsel for the appellants submitted that the primary judge rejected the analysis of Gordon J in Stubbings, but that analysis is now the law. He submitted that the primary judge said that you cannot go beyond the analysis in ss 21 and 22 and that those sections set the limit. He submitted that that approach has been rejected and is just wrong. He submitted that the primary judge’s distillation of principles described as “intellectual fairy floss” were the very statements of principle which have been adopted by the High Court as the proper approach.

Consideration

[120] In our opinion, the appellants’ submissions cannot be accepted.

[121] As we understand the argument, it is essentially that: (a) Productivity Partners stands for the proposition that the task of the court, in applying ss 21 and 22, is to search for and apply accepted and acceptable community standards; and (b) the primary judge erred by rejecting the search for, and the application of, such standards.

[122] In our view, the premise of the argument is not correct. We do not read the judgments in Productivity Partners as establishing that the task of the court is to search for and apply accepted and acceptable community standards. Rather, we read those judgments as standing for the proposition that ss 21 and 22 recognise or embody certain accepted and acceptable community standards. Importantly, it is the statutory notion of unconscionability against which conduct is to be evaluated.

[123] Productivity Partners was a proceeding brought by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission against Productivity Partners Pty Ltd (trading as Captain Cook College) (the College), a vocational education and training provider. At first instance, the trial judge found that the College had engaged in unconscionable conduct in contravention of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law and that Mr Wills (the acting CEO of the College for part of the relevant period) was knowingly concerned in the College’s systemic unconscionable conduct. On appeal to the Full Court of the Federal Court, by a majority, the appeal was dismissed. The Full Court did, however, interfere with the trial judge’s decision as to the date from which Mr Wills was knowingly concerned in the College’s contravention of s 21. The College and Mr Wills appealed, with special leave, to the High Court of Australia.

[124] The High Court dismissed the appeal, a conclusion in which all seven members of the High Court joined. All members of the High Court affirmed the conclusion of the trial judge and the majority in the Full Federal Court that the College engaged in unconscionable conduct in contravention of s 21. Further, all members of the High Court were of the view that the date from which Mr Wills was knowingly concerned was the date decided by the trial judge. Separate judgments were delivered by: Gageler CJ and Jagot J; Gordon J; Edelman J; Steward J; Gleeson J; and Beech-Jones J. In relation to the meaning of “unconscionable conduct” in s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law, Steward J (at [282]), Gleeson J (at [314]) and Beech-Jones J (at [340]) agreed with the reasons of Gordon J. In relation to the disposition of grounds one and two of the College’s appeal (which concerned whether the College engaged in unconscionable conduct), Gleeson J (at [310]) and Beech-Jones J (at [340]) agreed with the reasons of Gageler CJ and Jagot J. We will therefore focus on the judgments of Gageler CJ and Jagot J, and of Gordon J.

[125] Gageler CJ and Jagot J rejected the College’s contention that s 22 of the Australian Consumer Law limited the scope of s 21: at [50]. Their Honours also rejected the proposition that the presence or absence of each matter specified in s 22(1)(a)-(l) constituted, in and of itself, a mandatory relevant consideration to be weighed in the circumstances of every case: at [54]. In the course of rejecting that proposition, their Honours said at [56]:

… the matters in s 22(1)(a) – (l) are non-exhaustive. As such, they embody “the values and norms recognised by the statute” by reference to which “each matter must be judged” to the extent that it “appl[ies] in the circumstances” [Stubbings at [57]].

(emphasis added)

[126] The language that the s 22 factors “embody” values and norms “recognised by the statute” is inconsistent with the appellants’ proposition that the court’s task is to search for and apply accepted and acceptable community standards.

[127] After referring to five key aspects of the provisions, their Honours stated at [60]:

That the presence or absence of each matter in s 22(1) is not a mandatory relevant consideration to be weighed by a court in every case, irrespective of the circumstances, does not mean that the required evaluation involves nothing more than, as the College put it, an “instinctive reaction that the legislation sought to avoid”. The normative standard set by s21(1) is tethered to the statutory language of “unconscionability”. While that term is not defined in the legislation and, in its statutory conception, is “more broad-ranging than the equitable principles”, it expresses “a normative standard of conscience which is permeated with accepted and acceptable community standards” [Stubbings at [57]], and conduct is not to be denounced by a court as unconscionable unless it is “outside societal norms of acceptable commercial behaviour [so] as to warrant condemnation as conduct that is offensive to conscience” [Kobelt at [92]. See also Stubbings at [58]]. The items listed in s 22(1)(a) – (l) are matters that the legislation requires to be considered, in the overall evaluation of the totality of the circumstances to be undertaken for the purpose of s 21(1), if and to the extent those matters are applicable. This is why both “close attention to the statute and the values derived from it, as well as from the unwritten law” [Kobelt at [153]] and “close consideration of the facts” [Kobelt at [217]] are necessary.

(some footnotes omitted; emphasis added)

[128] In the above passage, their Honours referred to Stubbings at [57] and [58]. In those paragraphs, Gordon J stated:

- Section 12CB of the ASIC Act, like equity, requires a focus on all the circumstances. The court must take into account each of the considerations identified in s 12CC if and to the extent that they apply in the circumstances. The considerations listed in s 12CC are non-exhaustive, but they provide “express guidance as to the norms and values that are relevant to inform the meaning of unconscionability and its practical application”. They assist in “setting a framework for the values that lie behind the notion of conscience identified in s 12CB”. “The assessment of whether conduct is unconscionable within the meaning of s 12CB involves the evaluation of facts by reference to the values and norms recognised by the statute, and thus, as it has been said, a normative standard of conscience which is permeated with accepted and acceptable community standards. It is by reference to those generally accepted standards and community values that each matter must be judged”.

- Put in different terms, the s 12CC considerations assist in evaluating whether the conduct in question is “outside societal norms of acceptable commercial behaviour [so] as to warrant condemnation as conduct that is offensive to conscience”. A court should take the serious step of denouncing conduct as unconscionable only when it is satisfied that the conduct is “offensive to a conscience informed by a sense of what is right and proper according to values which can be recognised by the court to prevail within contemporary Australian society”.

(footnotes omitted; emphasis added)

[129] We do not read either of the above passages as suggesting that the test of unconscionability in s 21 involves application of a standard of conscience defined by community standards in the abstract (ie untethered from the statute). Rather, we read those passages as standing for the proposition that the statutory provisions (both ss 21 and 22) “recognise” certain values and norms. It is in this sense that the statutory test is “permeated” with accepted and acceptable community standards.

[130] The same analysis applies, in our opinion, to the judgment of Gordon J in Productivity Partners. In that case, her Honour stated:

- The s 22 factors are non-exhaustive. They provide “express guidance as to the norms and values that are relevant” to, and inform the meaning of, “unconscionable” in s 21(1) and its practical operation. These norms and values include “certainty in commercial transactions, honesty, the absence of trickery or sharp practice, fairness when dealing with customers, the faithful performance of bargains and promises freely made” and the protection of the vulnerable.

- As was explained in Stubbings [at [57]], the s 22 factors “assist in ‘setting a framework for the values that lie behind the notion of conscience identified in [s 21] ’”. The s 22 factors “assist in evaluating whether the conduct in question is ‘outside societal norms of acceptable commercial behaviour [so] as to warrant condemnation as conduct that is offensive to conscience’” [ Stubbings at [58]].

- The ACL does not require a plaintiff in every case to “plead and adduce evidence of facts directed to” the factors in s 22(1). Nor is there warrant for construing the factors in s 22 as “statutory criteria” that set the metes and bounds within which the normative standard prescribed by s 21(1) is to be applied. Neither the text or context of ss 21 and 22 of the ACL, nor the authorities that have considered those provisions, provide any support for that approach.

- To treat the matters in s 22 as a mandatory set of factors to be applied mechanistically when analysing whether s 21 has been contravened would be contrary to the text of the ACL. It would impermissibly limit the court’s capacity to consider the totality of the circumstances that might render a particular person’s conduct, system of conduct or pattern of behaviour unconscionable.

- Unconscionability has been described as “a normative standard of conscience which is permeated with accepted and acceptable community standards” [Stubbings at [57]]. But, as we know, values, norms and community expectations can develop and change over time: “[c]ustomary morality develops ‘silently and unconsciously from one age to another’, shaping law and legal values”. Indeed, standards from earlier times can be, in some respects, rougher and, in other respects, more fastidious. Different standards of commercial morality apply in other lands.

(emphasis added; some footnotes omitted)

[131] We do not read the above passage (or the passage in Gordon J’s judgment at [150]–[151]) as suggesting that the test of unconscionability is untethered from the statutory language. To the contrary, those passages reinforce the point that the statutory provisions recognise and give effect to certain accepted and acceptable community standards, and that the court’s role is to apply a standard prescribed by the statute.

[132] In Productivity Partners, Edelman J considered the relevant principles concerning unconscionable conduct under s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law commencing at [229]. His Honour’s discussion included:

- The legislative proscription by reference to “conscience” contains layers of uncertainty. Conscience, from the Latin conscientia, denoting a holding of knowledge, has shades of meaning generally related to a subjective recognition of the moral and ethical qualities of action. Locke described conscience as “nothing else but our own opinion … of our own actions”. But Parliament must be taken to have contemplated an assessment of whether conduct is unconscionable by reference to objective standards rather than to a judge’s personal or subjective opinions. Nor is there any indication that the objective standard of assessment should involve a judge’s best guess, or a survey of the empirical evidence, as to the standards of a community, even if such monolithic standards can be taken to exist in a plural society. “Compassion will not, on the one hand, nor inconvenience on the other, be to decide; but the law”.…

- The difficulty with the application of the values of Australian common law and statute is that they apply at such a high level of generality, and can point in so many different directions, that the concept of unconscionability has been said to be no more useful than the category of “small brown bird” to an ornithologist. …

- Section 22 of the Australian Consumer Law does not codify the values of Australian statute and common law, nor does it resolve such difficulties in application. Rather, it articulates a list of wide-ranging matters to consider when applying these values, including: …

- In applying the relevant values of Australian common law and statute, all matters and circumstances enunciated in s 22 that are potentially relevant must be considered. So too must any other circumstance that potentially bears upon standards of trade and commerce be considered. Otherwise, the assessment of conscience will have proceeded by reference only to a subset of the relevant values. …

(footnotes omitted; emphasis added)

[133] The above passage does not provide any support for the appellants’ submission that the task of the court is to search for and apply accepted and acceptable community standards.

[134] As already noted, Steward J (at [282]) agreed with Gordon J’s expression of principle concerning the relevant meaning of “unconscionable conduct”. Steward J noted that Gordon J in Stubbings adopted the following passage from the reasons of Nettle and Gordon JJ in Kobelt (at [234]):

The assessment of whether conduct is unconscionable within the meaning of s 12CB [of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth)] involves the evaluation of facts by reference to the values and norms recognised by the statute, and thus, as it has been said, a normative standard of conscience which is permeated with accepted and acceptable community standards. It is by reference to those generally accepted standards and community values that each matter must be judged.

(emphasis added)

[135] As this passage makes clear, the impugned conduct is to be assessed against the values and norms “recognised by the statute” rather than accepted and acceptable community standards at large.

[136] In the context of discussing the role, if any, of the notion of “moral obloquy”, Steward J stated:

- It is unclear what is meant by a “normative standard”; by “societal norms” of commercial behaviour; or by “generally accepted” “values and norms”. These somewhat anaemic concepts appear to mask, or skate over, necessary analysis in accordance with a known methodology. To borrow the words of Professor Birks, it looks like an attempt to “clothe” equitable principle “in more grown-up words”.

- In that respect, the required “normative standard” cannot be that of Australia’s judiciary; it is not what each judge subjectively, and perhaps collectively, believes to be an acceptable standard of commercial behaviour. If it meant that, commercial life really would be subject to judicial caprice or, worse, mere fashion. It should not, with very great respect, be a “free-form choice”.

- Nor should recourse to generally accepted “values and norms” be seen as a reference to some form of empirical enquiry into what most Australians might think is a normative standard of behaviour. If it was, how would a judge discern it? Would it be a matter for expert evidence of some kind? Would it be a matter of judicial notice? What if many standards exist: a possibility which is real enough in a multicultural society which may no longer exhibit “monolithic moral solidarity”. And what if the standards themselves are offensive or become so? It was undoubtedly the case that some Australian “values and norms” held before the Second World War would now be considered entirely repulsive. That includes standards about racial bigotry.

(footnotes omitted; emphasis added)

[137] These statements, in particular the first sentence of [292], are inconsistent with the appellants’ submission that the court’s task is to search for and apply accepted and acceptable community standards.

[138] As noted above, Gleeson J agreed (at [310]) with the reasons of Gageler CJ and Jagot J in relation to grounds one and two of the College’s appeal. Gleeson J also agreed (at [314]) with Gordon J’s analysis of the meaning of “unconscionable conduct” in s 21. Gleeson J wrote separately to explain the two ways in which s 22 informs the analysis required for a conclusion that conduct is unconscionable within the meaning of s 21. In the course of that explanation, Gleeson J stated:

- First, s 22 provides “express guidance as to the norms and values that are relevant to inform the meaning of unconscionability and its practical application”. Unconscionability within the meaning of s 21(1) is itself a standard. However, the content of the statutory standard of unconscionability is not obvious because Parliament has appropriated, without definition, the terminology of “unconscionability”. Under the general law, “unconscionability” is a value-laden concept by which a person’s conduct is judged against “standards of personal conduct compendiously described as the conscience of equity”. Since s 21(1) is “shorn of the constraints of the unwritten law”, it may apply in a case that involves a departure from “societal norms of acceptable commercial behaviour” that would not ground a claim for relief under the general law.

- The terms “norm” and “value” are overlapping. Generally, a norm is a standard of conduct, such as a standard set by an industry code. A value, which could encompass a norm, is a quality that is desirable. In these reasons, I will refer simply to standards.

- Secondly, s 22 provides relevant guidance by “setting a framework for the values that lie behind the notion of conscience” in s 21(1). Section 22 facilitates the identification of “the circumstances”, within the meaning of s 21(1), in which allegedly unconscionable conduct must be assessed by listing, non-exhaustively, “matters” to which the court “may have regard” in deciding whether the conduct has contravened s 21(1).

(footnotes omitted; emphasis added)

[139] The above passage and the passage at [319]–[321] reinforce that the statutory provisions recognise and give effect to certain norms and values. The passages do not provide support for the appellants’ submissions.

[140] We are reinforced in our view that there is no error in the primary judge’s statement of principles by the fact that the primary judge relied (at J[3504]–[3505]) on the judgment of Gageler J in Kobelt (at [87]) and the judgment of Nettle and Gordon JJ in Kobelt (at [153]). The judgments of Gageler CJ and Jagot J and of Gordon J in Productivity Partners do not indicate any departure from those passages in Kobelt. To the contrary, Kobelt at [87] is cited in the footnotes to the judgments of Gageler CJ and Jagot J and of Gordon J.

[141] Insofar as the appellants relied on the judgment of Allsop CJ in Paccioco, and the adoption of parts of that judgment by members of the High Court in Productivity Partners, we do not see any substantive relevant difference between those statements of principle and the primary judge’s judgment. As set out above, the primary judge specifically relied on Allsop CJ’s judgment in Paccioco in formulating J[3510], as the primary judge explained at J[3511]. To the extent that J[3511] queried whether “the values and norms that inform the living Equity” play much of an additional useful role in the context of statutory unconscionability to the extent that they are not already enshrined in ss 21 and 22, the primary judge’s qualification was carefully calibrated and this is not a matter that was the subject of detailed analysis in Productivity Partners.

[142] In summary, no error is shown in the primary judge’s statement of the applicable principles. We do not consider there to be any difference as a matter of substance between the primary judge’s statement of the applicable principles and those set out by the High Court in Productivity Partners. In the passages criticised by the appellants, the primary judge was not seeking to convey that accepted and acceptable community standards are irrelevant to ss 21 and 22 of the Australian Consumer Law. Rather, his Honour was making the point that in applying s 21, the Court is to be guided by norms and values recognised by the statute (ie those identified at J[3510]), not carry out its own inquiry as to the content of accepted and acceptable community standards in the abstract. His Honour was correct to do so.

…

(emphasis added)

The link to the full case is here.

The SASCA analyses all the current case law: Rangelea Holdings Pty Ltd v Anyamathanha Traditional Lands Association & ors [2025] SASCA 32.

The continuing controversy

Escheat is a feudal doctrine and an incident of the doctrine of tenure under which no land could be without an owner.1

As Hetyey AsJ noted recently in Re Energy Brix Australia Corporation Pty Ltd,2 “In essence, under common law, escheat refers to a situation whereby a fee simple interest in real property comes to an end and ownership in the property re-vests or reverts in the Crown. The radical title in the property merges in the Crown, which is then entitled to re-grant the land as it sees fit. As explained by the learned author of Butt’s Land Law, under an escheat, the Crown takes back what had always been its own property, subject only to the intervening (but now ceased) rights that had been granted to the tenant or holder of the property.”

It finds its modern practical emanations only in the insolvency regime under section 133 of the Bankruptcy Act and section 568F of the Corporations Act. Both sections contemplate that the trustee\liquidator in charge of an insolvent estate might “disclaim” property which does not enure to the benefit of creditors; in such a case, the property is then said to “escheat” to the Crown. (Whether under the Torrens system such a transfer to the Crown may occur is the subject of ongoing judicial controversy but is, happily, of little practical importance).3

Escheat to the Crown is qualified by the vesting power under s 568F of the Corporations Act or the court setting aside the disclaimer under s 568E. There is also a tension between the doctrine of escheat, which relies on a feudal concept of tenure, and the modern statutory basis for a registered proprietor’s interest in real property.

The provisions of section 568 of the Corporations Act

In ANZ v Fairfield City Council4 Emmett J discussed the operation of section 568.

Section 568(1)(a) of the Corporations Act relevantly provides that a liquidator of a company may, at any time, on the company’s behalf, disclaim property of the company that consists of “land burdened with onerous covenants”. Under s 568A(1), the liquidator must, as soon as practicable after disclaiming property, give written notice of the disclaimer to each person who appears to the liquidator to have an interest in the property. Under s 568B(1), a person who has an interest in disclaimed property may apply to the Court for an order setting aside the disclaimer before it takes effect, but may only do so within 14 days after the liquidator gives such notice to that person. Under s 568C(1), a disclaimer takes effect if, and only if, relevantly, no such application is made to the Court. Under s 568C(3), such a disclaimer is taken to have taken effect on the day after the day when the liquidator gave notice under s 568A(1).

24. Under s 568D(1), a disclaimer is taken, as from the day on which it is taken to take effect by the operation of s 568C(3), to have terminated the company’s rights, interests, liabilities and property in or in respect of the disclaimed property. However, a disclaimer does not affect any other person’s rights or liabilities, except so far as necessary to release the company and its property from liability.

25. Under s 568E, a person who has, or claims to have, an interest in disclaimed property may apply to the Court, with the leave of the Court, for an order setting aside the disclaimer after it has taken effect. The Court may set aside a disclaimer only if satisfied that the disclaimer has caused, or would cause, to persons who have, or claim to have, interests in the property, prejudice that is grossly out of proportion to the prejudice that setting aside the disclaimer would cause to the company’s creditors and persons who have changed their position in reliance on the disclaimer taking effect. Finally, s 568F relevantly provides that the Court may order that disclaimed property vest in, or be delivered to, a person entitled to the property or a person to whom it seems to the Court appropriate that the property be vested or delivered.

26. The purpose of providing for disclaimer by a liquidator in a winding up is to enable the liquidator to rid the company of burdensome financial obligations that might otherwise continue to the detriment of those interested in the winding up of the affairs of the company. The power to disclaim is given to enable the liquidator to advance the prompt, orderly and beneficial administration of the winding up of the affairs of the company.”

Obtaining a “vesting order”

Under the section a party interested in the property (say as mortgagee) may seek a “vesting order” to enable the property to be sold and the security paid out and it is this circumstance which provokes the recent cases. The authorities make it clear that any supervening third party must be joined to the proceedings by the mortgagee (whether supported by caveat or not).5 The relevant principles applying to the Court’s discretion to vest property in a mortgagee applicant have been helpfully summarised by Derrington J in Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Queensland; in the matter of Hewton6 as follows:

“(1) The reference to “property” in the section includes a reference to any land which is burdened with “onerous covenants”, and that includes any financial obligations which can be enforced against the land: Re Tulloch Ltd (in liq) and the Companies Act (1977) 3 ACLR 808, 812; ING Bank (Australia) Ltd v Queensland, Re of Watson [2017] FCA 411 (ING v Queensland) [15];

(2) A disclaimer operates immediately to determine the rights, interests and liabilities of the bankrupt and their trustee in respect of the property: s 133(2) of the Bankruptcy Act: and its effect is not dependent upon the registration of a notice of the disclaimer by the trustee: Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Western Australia, Re of Arbidans (a Bankrupt) [2020] FCA 1514 (CBA v WA ) [19]; Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Queensland [2019] FCA 1362 [4];

(3) Where a trustee, who only holds an equitable title in a bankrupt’s land because the bankrupt remains the registered owner, disclaims under s 133, the effect is to disclaim both that equitable interest and any legal interest of the bankrupt who remains registered under the relevant Torrens system legislation

(citation omitted)

(4) The primary consequence of disclaiming the fee simple interest is to cause of the process of statutory escheat to take effect with the consequence that full and complete title to the land vests in the Crown. Any existing mortgage over the fee simple interest is not enforceable against the Crown which has given no covenants to repay any money: Bank of Queensland Ltd v Western Australia [2020] FCA 442 [36].

(5) However, it is now accepted that the erstwhile legal and equitable interests in the fee simple are not dissolved, and nor do they merge in the superior title; cf Purefoy v Rogers [1845] EngR 195; (1669) 85 ER 1181; with the consequence that the fee simple, which is taken to vest in the Crown, remains subject to any securities attaching to that interest (citation omitted);

(6) It follows that subsequent to the making of the disclaimer by the trustee, a person with an interest in the fee simple, such as mortgagee, may make an application under s 133(9) of the Bankruptcy Act for the vesting of the property in them: National Australia Bank Ltd v Victoria [2010] FCA 1230; (2010) 118 ALD 527, 530 [9]–[12]. It is possible that in the absence of the making of an order under this section the mortgagee will not be able to enforce their security: NAB v Queensland 16;

(emphasis supplied)

(7) Prima facie, it is just and equitable to vest title to the disclaimed fee simple interest in land in an unsatisfied security holder whose security exists over that interest because the making of an order removes all doubt as to the veracity of any other action by a security holder to recover their debt (ANZ v Queensland [23]), to refuse to make the order would diminish the value of securities including registered securities, the disclaiming by the trustee strongly indicates that the security holder’s claim exceeds the land’s value, and the security holder has an interest to realise the land for the highest value: ING v Queensland [31]–[ 33];

(8) It is usually the case, and especially so in circumstances where the debt of the security holder exceeds the value of the land, that a Court will make orders liberalising the holder’s ability to sell the land so that it may do so without compliance with statutory obligations relating to the exercise of the power of sale by security holders. That, is subject to the making of orders, such as the requiring of the making of an account, which ensure the security holder does not receive more than the amount to which it is entitled: Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd v Queensland [2016] FCA 1221; Ginn [19]; ING v Queensland [38]; ANZ v Queensland [25]; NAB v Queensland [25]. The orders sought and made in the present case are what have become the standard suite of orders giving effect to these matters.

In National Australia Bank Ltd v New South Wales7 Perram J held that a vesting order may be made if the applicant bank can demonstrate (a) that a disclaimer to relevant property has occurred within the meaning of s 133; (b) that the applicant has an interest in the disclaimed property within the meaning of s 133(9); and (c) that the applicant is entitled to the disclaimed property or that the Court considers it to be just and equitable that it should be so vested or delivered.

Thus, an escheat does not deny the position of any prior security holder over the property. As Gardiner Ass J recently observed in Re Kralcopic Pty Ltd (deregistered)8 “When a third party has a security interest over the property such as a mortgage or a charge, those interests survive the vesting. The State’s ownership of the land that has escheated to it is subject to any existing mortgages or charges and if [the caveator] had not withdrawn its caveats it would have been necessary to make it a party to the proceeding.”

Recent cases

As Jackson J noted in Westpac Banking Corporation v State of Western Australia; in the matter of Conco Construction Service Pty Ltd9

“The effect of the liquidator disclaiming the Canning Vale property is that the fee simple escheated to the Crown in right of the State, subject to any existing mortgages or charges: Tonic Pty Ltd v State of South Australia [2019] FCA 1361 at [8] (Charlesworth J). Although there is no personal covenant upon which Westpac as mortgagee can take action against the Crown, the escheat does not erase the rights that have accrued from the mortgagor’s default. However the disclaimer does mean that in the absence of a vesting order, the mortgagee will not be able to take any action to realise the security. See AFSH Nominees Pty Ltd v State of Western Australia [2022] FCA 1168 at [15]-[21] (Colvin J) applying, among other authorities, Bank of Queensland Limited v State of Western Australia [2020] FCA 442 at [36] (McKerracher J). The mortgagee, as a person claiming an interest in the property, may make application for the vesting order: s 568F(2)(a).

21. In Sullivan v Energy Services International Pty Ltd (in liq) [2002] NSWSC 937 at [37]-[40] Young CJ in Eq traced the legislative history of the provision. The relevant standard for a vesting order was originallythat it seem ‘just’ to the Court, in 1981 the relevant adjective was changed to ‘proper’ (in the Companies Code), and in s 568F it must seem to the Court that it is ‘appropriate’ that the property be vested. There is no reason to think that these changes in wording changed the substance of the standard to be applied. Also, there are obvious parallels between s 568F and the cognate provision of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth), s 133(9), where the standard is that it be ‘just and equitable’ that the property vest in the person: see e.g. AFSH Nominees at [20].

Surplus funds and the liquidator’s fees

What if there is a surplus after the mortgagee has sold the property pursuant to a vesting order under the legislation? May the trustee or liquidator make a claim to the balance notwithstanding that the property was disclaimed? On this topic, in ANZ v Victoria; in the matter of Paksoy10 O’Bryan J recently said:

“If there are surplus funds paid into Court, the Trustees have foreshadowed that they may make a claim to the funds over the State. The Trustees’ entitlement to make such a claim, in circumstances where they have disclaimed the Property, is presently a hypothetical question which need not be determined. The practice of the Court in cases such as the present is to require the mortgagee to provide an account of its payments and receipts and to serve a copy on the State (as respondent) and the trustee(s) in bankruptcy. The preparation of an account helps to ensure that the mortgagee does not receive more than the amount to which it is entitled, and places the State and the trustee(s) in bankruptcy in a position to make an application to the Court in respect of any surplus funds as they consider appropriate: see National Australia Bank Ltd v State of Queensland [2019] FCA 1780 at [25] (Derrington J); ING Bank (Australia) Ltd v State of Queensland [2017] FCA 411 at [38] (Derrington J). Although ANZ did not seek orders to that effect, I consider it appropriate to order that, within 30 days of the sale, ANZ must provide an account of its payments and receipts to the State, the Trustees and the Registrar of the Court.”

Conclusion

The recent authority, discussed above, indicates that the vesting of disclaimed property in a mortgagee is a mundane and daily forensic occurrence. The exquisite questions remain:11 does the disclaimed title escheat absolutely to the Crown since the Court may make an order vesting it in someone else? does any “just terms” question arise if unsecured creditors are deprived of a surplus on the sale of the property? does the property fall into the Crown in right of the Commonwealth, or the State? Happily, such questions may await argument and decision in the unlikely event that anything ever turns on them.

1 See my earlier detailed discussion, Aitken, “Bankruptcy, escheat and the mortgagee’s interest – topics `as clear as mud’ in theory but simple in practice” (2020) 36(8) Banking Law Bulletin 119. The flood of cases on the topic has continued. I have long had an interest in this rather abstruse area which dates from my successful (unusually!) appearance in the landmark case of Sullivan v Energy Services International Pty Ltd (in liq) [2002] NSWSC 937 at [37]-[40] before Young CJ in Eq who traced the legislative history of the Corporations Law provision.

2 [2022] VSC 700 at [25] (citation omitted).

3 See the detailed analysis of all the possible difficulties in the judgment of Rares J in NAB v NSW [2009] FCA 1066 where his Honour discusses the history of the doctrine and its possible interplay with registered title.

4 [2016] NSWSC 668 at [23] – [26].

5 See, for example, the decision of Logan J in Westpac Banking Corporation; in the matter of Burton (a bankrupt) v Burton [2021] FCA 773. And see the detailed discussion on the full extent of a mortgagee’s interest upon sale and the consequences which flow from it in Point Coolum Ltd v Queensland [2022] QSC 291 per Williams J.

6 [2021] FCA 22 at [15].

7 [2014] FCA 298 at [11].

8 [2023] VSC 306 at [25].

9 [2022] FCA 1213 at [20] – [21].

10 [2023] FCA 62

11 See NAB v NSW footnote 2 above at [23] – [28] per Rares J.

“Virtual courtrooms, smart contracts, PEXA and knowledge base technology will ultimately allow graduate lawyers to use their time more effectively. Graduates will be able to focus their time on more substantial and complex legal work and possibly gain more client face time. Virtual courtrooms will allow the graduate to work from their office on `stand by’ until the court is ready for their appearance”.[1]

“This is Supreme Court calling, Supreme Court calling. Are you there, Mr Bullfry? Are you receiving me? Are you receiving me?”

“Yes, your Honour, loud and clear. I am here and looking for some face-time. We do not tolerate any Luddites in our chambers although a mishap on Tinder recently caused me a certain amount of matrimonial gene. Grinder and other social applications are banned during business hours. Will your Honour kindly go to Plaintiff’s Document 134 in the electronic bundle. It is the PEXA document which was electronically filed recently in the LTI. Unfortunately, due to a fire wall breach someone(!) seems to have altered both the name of the registered proprietor and the mortgagee which, I will argue, attracts the operation of section 43A of the Act. As a result, the EFT settlement, so it would appear, has vastly enriched persons unknown in southern Cebu.”

“I am sorry, Mr Bullfry, the server at this end has gone down and my AUSTLII version of the Act appears to be out of date. Is the document itself in hard-copy?”

“I am afraid not, your Honour. The Chief Justice’s latest practice direction (No 845(A2) of 2019) specifically states that “no hard-copy document” shall be prepared for any audio-visual interlocutory application. This is particularly so where the Torrens `knowledge base’ is to be invoked at the hearing”.

“Well, let’s proceed. Do we need to encrypt?”

“I don’t think so, your Honour. My present venue is blameless, and I am sure that your Technical and Computer Services Tipstaff (TCST) has carried out the daily `sweep’ of your courtroom on Level 7 now required under the Chief Executive’s ruling. I trust that the new equipment is no longer causing problems with your pacemaker”.

“All right then. Call the witness”.

“Is she to be pixelated, or not, your Honour? In the latter case I will have trouble leading her because the link with Tamworth is likely to go down at any time, and the NBN (mirabile dictu) does not have sufficient bandwidth for the connection to send both images and sound at the same time.”

“But Mr Bullfry, this should all have been worked out with the Registrar in the Monday List – I thought that a specific order had been made about pixelation?”

“No, your Honour. The only order made required a complete “voice disguise” to prevent identification but unfortunately all that could be heard during the virtual training session was a

series of harsh, guttural groans. That would undoubtedly have had an effect on your Honour’s findings on credit.”

“Mr Bullfry, are you actually in the virtual courtroom? There is a large amount of background noise at this end”.

“Ah, your Honour is too quick for me. I am, in fact, addressing you via the Court’s I-phone app on my Android 8 from a popular shebeen in Castlereagh Street and the background noise your Honour heard was just my fellow drinkers revelling in the fall of the sixth Sri Lankan wicket. I have of course been on `stand-by’ for some time but the problem with the West Australian time zone made it a matter of personal imperative for me to get in some face time down here before addressing your Honour.”

“Mr Bullfry, the new protocol was not designed to allow you to `appear’ from any location you may happen to choose at the time. Are you robed? Give me a “reverse selfie” so that I can make sure that I can `see’ you”.

“I had better not do that, your Honour. I am in what my late father would have called “mess undress”, and although the sarong is rather fetching and culturally appropriate, given that the contract was made in Malaysia, the T-shirt is not”.

“But that seems to be one of the problems with the “smart contract”, Mr Bullfry. Whoever “drafted” this one used the old electronic boilerplate so that the choice of law clause has defaulted to North Korea, not Malaysia”.

“Well, your Honour, the High Court has dealt with the question of renvoi recently in a judgment which is, fortunately, available only in electronic form and the copy I have on my Kindle is not compatible with Word 14 which means that I can only send to you my highlighted version”.

“But Mr Bullfry, that would be a gross breach of protocol – particularly if you have failed to remove the marginal comments in yellow such as those which marred your latest submission”.

“Your Honour, we have apologised to both you and to our opponents for any distress which those inadvertent comments caused. I will not be hitting `Reply all’ again any time soon. Ms Blatly was absent-mindedly typing in my apercus on various aspects of our opponent’s submissions (and some reflections on his personal appearance) and they should not have been retained in the final version. May we simply describe them as pentimento?”

“Well, we had better sort out the further televisual directions for hearing. First, Mr Bullfry, you are not to use any form of avatar whatsoever on any further occasion during the course of this hearing. Do I make myself clear? Nor will I tolerate any further analogies between the defendant’s company and Game of Thrones or for there to be any mention of Youtube while you are cross-examining. It does not make any difference that I am a “friend” of your opponent’s junior on Facebook and that is not a ground for disqualification, or for me to recuse myself. Nor, may I repeat, is the fact that I have twice rejected a “friend” request from you – and that decision is not liable to any form of judicial review. We are now living in an electronic age and these things are to be expected”.

“Six degrees of separation, indeed, your Honour.”

“Mr Bullfry, I am afraid my TCST has just advised me that we are about to lose the link at this end. I had better make some further interlocutory orders …. ZZZZZZZZZZZZZPPPPPTTTT!!!!

(Bullfry’s screen went blank and the matter was subsequently adjourned sine die when it was found to be impossible to restore the connection to either Castlereagh Street or Tamworth due to the combined failure of the cable, and the broadcast facility).

[1] P Melican, A Bell-Rowe, A Patajo and H McDonald, “The law and the legal profession in the next decade: the student’s perspective” (2016) 90 ALJ 434 at 440.

This article was published in the New South Wales Bar News in its Summer 2023 issue. Bullfry is the character of literature Jack Bullfry of counsel. He is the creation of lawyer and former Queensland University lecturer Lee Aitken.

‘There is `bullying’ and then there is bullying,’ mused Jack Bullfry, as he looked at the day’s transcript, and sipped his Negroni. He had not raised his voice but had he, perhaps, displayed too much invective in his cross-examination? Things were certainly more robust years ago when he had started but the profession had changed for the better – litigation was not the blood sport it had been; the dishonourable art of ‘sledging’ had all but disappeared.

Thankfully, long gone are the days of the Irish Bar when Serjeant Armstrong used his most potent weapon, ‘ridicule.’ ‘His great weapon was ridicule. He laughed at the witness and made everyone else laugh. The witness got confused and lost his temper, and then Armstrong pounded him like a champion in the ring.’1

What to do when attacked by a judicial ‘bully’? First, remember when confronted by a fractious tribunal to keep Proverbs 15 front and centre: ‘A soft answer turneth away wrath: but grievous words stir up anger. The tongue of the wise useth knowledge aright: but the mouth of fools poureth out foolishness.’

The only reason counsel is deployed in a matter is because the instructing solicitor puts his or her faith in counsel to do two things: first, make sure by advice and otherwise that the matter is ready for judicial determination, and secondly, stand up in court and take the forensic fire as it descends.

That, of course, is a talent in the repertoire of every good advocate – that ability to disarm a judicial onslaught with guile, or charm, and make the worse appear the better case. And such onslaughts may, by definition, occur in even the best conducted matters.

In such a storm it is the bounden duty of counsel (although there was no Bar Rule about it) to confront the problem as best one can. Most importantly, on no account and on no occasion should the advocate point to those instructing him as the source of all the difficulty! And yet Bullfry had seen that sad, deflecting ‘excuse’ raised by weaker counsel on many occasions.

The only reason counsel is deployed in a matter is because the instructing solicitor puts his or her faith in counsel to do two things: first, make sure by advice and otherwise that the matter is ready for judicial determination, and secondly, stand up in court and take the forensic fire as it descends. Every solicitor is entitled to appear in any court in the Commonwealth – it is only a certain inner fecklessness (best left unexamined in almost every case) in the cadet branch of the profession which provides the separate Bar with its daily bread, and any work at all. If every solicitor was prepared to stand fire for putting difficult propositions to the court the Bar would cease to exist.

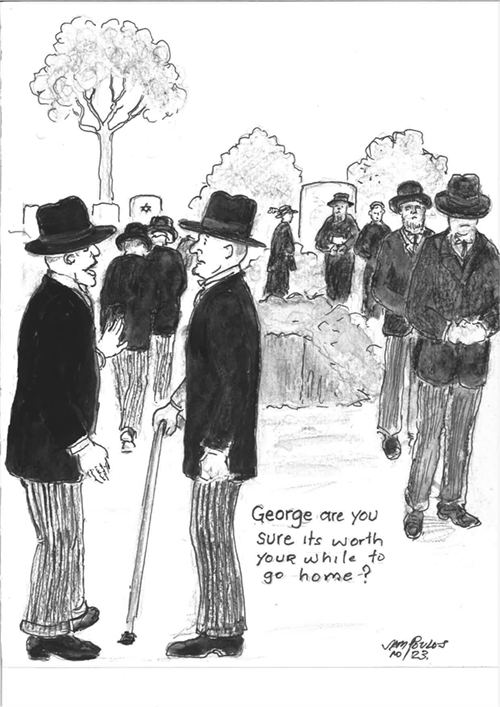

Jim Poulos

Bullfry recalled a fraught matter in which, before he was deployed, various judgment debtors had failed to abide by the relevant orders of the Court requiring them to account to certain ex-partners and obey certain directions. They had been misinformed that there was no need to do so on the most tendentious of technical bases. The matter came back for the fifth time on a contempt application and Bullfry said simply to the forbidding Equity Division judge: ‘Your Honour, I have explained the position to my clients and they now offer a full and open apology to the Court for their previous behaviour.’ The judge said, ‘That is the first time in five hearings, Mr Bullfry, that a proper explanation and apology for otherwise contumelious behaviour has been given to the Court’.

There are, of course, many legendary sharp exchanges between Bench and Bar. SEK Hulme fleshes out the famous retort of Hayden Starke to the High Court as told to him by Sir Garfield Barwick.2

No one announced an appearance for the respondent. The dreadful silence was broken by a very nervous solicitor telling the court that Mr Hayden Starke had been briefed, but he did not appear to be present. The court adjourned while Mr Starke was sent for. Mr Starke came up from Selborne Chambers, the case was called again, Mr Starke announced his appearance for the appellant, and sat down.

The Chief Justice, the vastly august Sir Samuel Griffith, intervened.

‘Mr Starke, the court is waiting.’

Mr Starke got to his feet, announced his appearance in a considerably louder voice, and sat down.

‘You do not take my point, Mr Starke. The court has been kept waiting, and the court expects an apology.’

That was not what the court got.

What it got was ‘This court is paid to wait. I am not.’

What intrigued Barwick was what in the ultimate the court could do. Was it contempt of court, to keep the High Court waiting? If not, was it contempt not to apologise for having done so? Was it all merely rude?

The questions remain open. He had always advised young barristers that those who lack the formidable forensic power, which Dixon saw in Starke, would do well not to learn the answers. They will do well to stay on hand. If something does go wrong, they will find it more comfortable, and possibly safer, to apologise.

(This anecdote was all of a piece with Starke’s ‘pitiless’ demeanour (Dixon CJ’s epithet). At the funeral of Sir Isaac Isaacs, Sir Garfield Barwick recalled an open grave ceremony held on one of the hottest days that Melbourne could record. As his erstwhile brothers filed past the open grave, Starke leant forward to his colleague and octogenarian, Sir George Rich, and asked ‘George, are you sure it’s worth your while to go home?’)

You must learn from your earliest days to resist any overbearing from the Court – but without ‘crossing the line’.

Secondly, don’t run before you can walk – if you have a criminal practice, start after a stint at Legal Aid or the Crown Prosecutor gaining experience in smaller matters in the criminal calendar – don’t let your first matter involve your client’s wife’s head in a refrigerator.

A distinguished commentator3 has said that:

‘… employers of legal practitioners have a responsibility to make sure that young lawyers are ready to go to court. That obligation requires that new lawyers are given sufficient training and support to appear in court with confidence and with mechanisms to overcome their natural anxiety. They should only be given court appearances commensurate with their experience and skill’.

You must learn from your earliest days to resist any overbearing from the Court – but without ‘crossing the line’. Fully forty five years ago, Bullfry had been a callow prosecutor. The chief magistrate, impatient to move matters forward, had told the police witness under examination-in-chief to hand over his notebook to speed up judicial note-taking. Foolishly, Bullfry acceded to the request. Almost immediately disaster struck when inadmissible material in the notebook came to light.

‘Mr Bullfry, I shall have to recuse myself now. This entire waste of time is down to your ineptitude.’

Bullfry returned, chastened to the office, where the Colonel simply grunted and said: ‘A lesson to be learnt, lad, a lesson to be learnt.’ Some weeks later the scene began to repeat itself. But this time Bullfry said simply, ‘Your Worship, we both came unstuck following that course recently, and it is not happening again!’

Good humour always has a part to play. Audley Gillespie-Jones4 recalled an incident before Sir John Barry who was out of temper with the conduct of the proceeding before him. Towards the end of the second day Trevor Rapke made a funny remark.

‘Everyone laughed except the judge who said: `I am sick and tired of those stupid remarks from the Bar table and the next person who makes one I shall fine for contempt of court and the fine shall be ten guineas.’

All the other counsel looked like zombies but Gill said, ‘I am not going to let him get away with that’ and stood up. Rapke said, ‘Don’t be a bloody fool’ and kept a tight grip on Gill’s gown.

Sir John Barry said, ‘What do you want?’

‘If I am unlucky enough to incur your Honour’s displeasure, may I have time to pay?’

Sir John brought up his clenched fist, then half-smiled and said:

‘That was funny. You were lucky.’

‘If I have done anything to dispel the horrible gloom caused by your Honour, it has served its purpose, and will you now ask Mr Rapke to let go of my gown!’

Courage and resolution on the part of counsel does not stop at an assertion of the right to conduct the case as counsel thinks best. Courage is not exhibited by inviting a trial judge to do as he pleases. It is the duty of counsel to represent his client. In that representation, it is his obligation to ensure his client’s case is presented and argued to the best of his skill and ability.

Counsel may, of course, be guilty of bullying behaviour – and this should not occur. It is never appropriate to lose one’s temper with the court, or to invite a judge to ‘do as you please,’ rather than to persuade the judge as the client’s interest properly demands and supports. As Kirby P noted5 in Escobar v Spindaleri:

‘Courage and resolution on the part of counsel does not stop at an assertion of the right to conduct the case as counsel thinks best. Courage is not exhibited by inviting a trial judge to do as he pleases. It is the duty of counsel to represent his client. In that representation, it is his obligation to ensure his client’s case is presented and argued to the best of his skill and ability. In these circumstances it is not the counsel who invites the judge to do as he pleases. It is a duty of counsel to endeavour to persuade the judge to do as his client’s interests necessitate, to the extent to which those interests might lawfully be pressed.

‘As has been said, in the atmosphere of the courtroom, emotions sometimes run high. But when they are indulged at the expense of the protection of the client’s interest, they ill-become counsel whose duty is to represent those interests.’ (Emphasis supplied.)

All this is, perhaps, a counsel of perfection. Some judges are naturally atrabilious, lack a judicial temperament, and have been worn down by the daily grind of obtuse, and unhelpful, submissions. Judging is a lonely post; it is easy to become ‘hoity toity’ when one’s behaviour is on daily public display – but ‘God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb.’

ENDNOTES

1. FL Wellman The Art of Cross-examination (1931 Macmillan) page 54 quoted by Ryan SC in ‘Propriety and impropriety in cross-examination’ Bar Association CPD Seminar 17 June 2008 at [31]. The entire paper repays the closest reading.

2. Victorian Bar News Autumn 2003 SEK Hulme, ‘Characters of Bench and Bar’ (a speech delivered 4 June 2002) pages 28 – 29.

3. Mr J Phillips SC, ‘Judicial Bullying’ delivered 4 August 2017 ((2018) 8 WWR 138).

4. AS Gillespie-Jones, The lawyer who laughed (1978) pages 25 – 26. Audley Sinclair Gillespie-Jones (1914 – 2000) was a celebrated VFL footballer (Melbourne and Fitzroy) and practised latterly in the ACT. For his obituary, see Victorian Bar News Spring 2000, page 20. Bullfry appeared against him many times in the late seventies; by that stage he was almost blind but indomitable.

5. (1986) 7 NSWLR 51 at 54 – 55.

Jim Poulos

Jim Poulos