Introduction

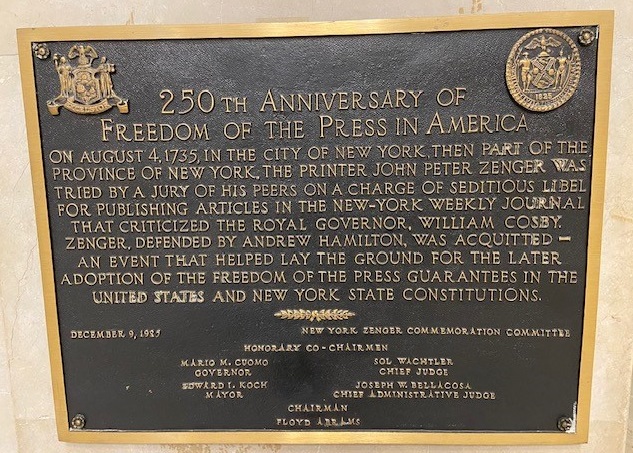

John Peter Zenger was tried for seditious libel in the New York Supreme Court in 1735. He was acquitted by a jury, contrary to the direction of the presiding judge, de Lancey CJ, as to the law. Zenger’s Case was a milestone in the evolution of certain fundamental freedoms in the United States of America, including freedom of the press. This article aims to show why Zenger’s Case is also important to an understanding of freedoms secured by Australian law.

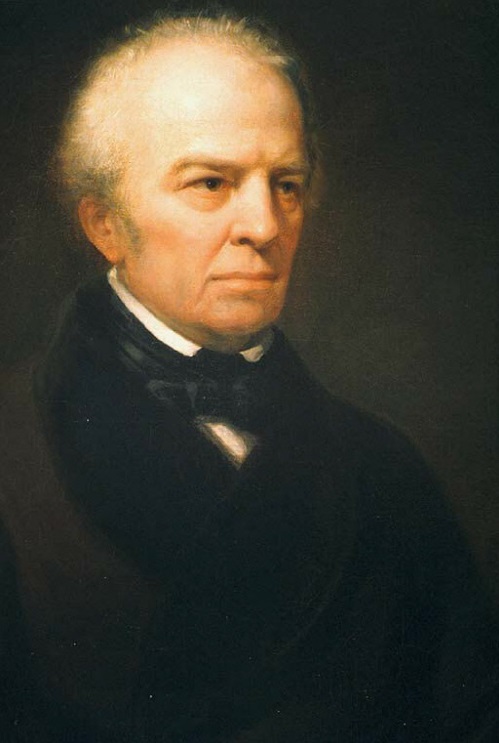

James de Lancey

It is convenient to begin by saying a few words about the presiding Judge, de Lancey CJ.

James de Lancey was born in New York City in 1703.

He came from a wealthy family.

He was educated in England, at Cambridge. He studied law at Inner Temple where he was called to the Bar.

In 1725, he returned to New York to practise law and enter politics.

In 1729, he was appointed to the New York Assembly.

In 1730, he was appointed a justice of the Supreme Court of New York.

In 1733, he was appointed Chief Justice, at the relatively young age of 30. He held that position until 1760. From time to time he served as Lieutenant Governor of the State of New York. In that capacity, in 1754, De Lancey granted the charter (under George II) for the creation of King’s College, now Columbia University.

As Chief Justice, he presided over the trial of John Peter Zenger in the New York Supreme Court in 1735. But there is a back-story.[1]

Cosby v Van Dam

In 1733, de Lancey J sat on a case involving a lawsuit brought by the newly appointed Colonial Governor of New York, William Cosby. Cosby had been appointed many months prior to his arrival in New York from England. Rip Van Dam was acting Governor in his absence. On his arrival in New York, Cosby sued Rip Van Dam, to recover one-half of the salary Van Dam had received in the meantime. Van Dam came from a well respected Dutch family. Cosby was quickly seen by native New Yorkers as an avaristic and nepotistic appointee. Cosby even passed an executive Ordinance specifically to allow him to bring the suit in a Court of Exchequer without a jury. He knew a local jury would rule against him.

Leading New York attorneys James Alexander and William Smith appeared for Van Dam, and argued that the commissions of the judges were invalid for two reasons: first, because they were only during the Crown’s pleasure, and not during good behaviour, and, second, because the Ordinance setting up the Court was made without legislative approval. Justices De Lancey and Frederick Phillipse, having royalist sympathies, rejected those objections and upheld Cosby’s claim. But Chief Justice Lewis Morris gave a strong dissent, which he then had published in pamphlet form.

In his anger, Cosby removed Morris from office, and made James De Lancey Chief Justice in his place.

This created a furore.

The New York Weekly Journal

Up until 1733, the sole newspaper in New York, the New York Gazette, was sympathetic to the government. But German immigrant John Peter Zenger, backed by Morrisite supporters, had lately set up an independent newspaper, the New York Weekly Journal.

Replica of the printing press used by Zenger, on display at Federal Hall, New York.

Zenger published articles critical of the Governor, in his Journal.

For example, it was said:

“The people of this City and Province think as matters now stand, that their liberties and properties are precarious and that slavery is [likely] to be entailed on them and their posterity … I think the Law itself is at an end. We see men’s deeds destroyed, judges arbitrarily displaced, new courts erected, without consent of the Legislature by which it seems to me, trials by juries are taken away when a Governor pleases, men of known estates denied their votes, contrary to the received practice… Who is then in that Province [to] call any thing their own or enjoy any liberty than those in the Administration will condescend to let them do it …”

Zenger was the publisher, not the author, of the critical articles. The authors were anonymous, but history has attributed the articles to James Alexander.

The Governor was furious and determined to have Zenger prosecuted to stop a repeat of those sentiments and in the hope that the identity of the true authors would come to light. Zenger, however, would not betray the identity of the authors.

The Information

Chief Justice De Lancey made two attempts to persuade the Grand Jury to indict Zenger for seditious libel, but on both occasions, unsuccessfully. The Attorney-General then presented an ex officio information for seditious libel, and Chief Justice De Lancey and Justice Phillipse issued a bench warrant for Zenger’s arrest. This was in 1734.

James Alexander and William Smith were retained to act for Zenger, and applied for bail. The evidence was that Zenger was worth £40. Chief Justice De Lancey set bail at £400, plus two sureties of £200 each. Zenger would spend 8 months in prison awaiting trial.

At the arraignment in 1735, James Alexander and William Smith challenged the commissions of the justices of the Supreme Court. That included the ground that the judges were appointed during pleasure. De Lancey CJ adjourned until the next day, where he and Phillipse J held James Alexander and William Smith in contempt and struck their names off the roll of attorneys permitted to practise in the Supreme Court.

Zenger applied to have an attorney appointed to act for him, and the Court appointed John Chambers. He was a newly admitted attorney, and considered sympathetic to the Governor. He was not expected to be very effective. But he surprised everyone. After entering a plea of Not Guilty, he sought a struck jury from the Clerk. The Clerk did not produce the Freeholders’ Book as usual, but produced a list of 48 potential jurors comprised of persons who were not Freeholders but most of whom had, at one time or other, held positions at the pleasure of the Governor. Mr Chambers then applied to the Chief Justice for a struck jury, and De Lancey CJ, probably thinking it would make no difference, ordered the Clerk to draw the jury panel out of the Freeholders’ Book in the presence of the parties, allowing such objections as may be just.

The Trial of Zenger

De Lancey CJ presided at the trial, which took place on 4 August 1735 in Old City Hall (the same building where the first Congress debated what would become known as the Bill of Rights in 1789).

Phillipse J also sat at the trial as second justice.

By the time the matter came on for trial, Zenger’s allies had been able to retain the pre-eminent colonial attorney Andrew Hamilton from Philadelphia. (No relation of Alexander Hamilton). He agreed to act pro bono. After Mr Chambers made his submissions, the appearance of Mr Andrew Hamilton was announced, to the surprise of the Court.

The received wisdom at the time in New York (as well as in England) was that truth was not a defence to seditious libel. All that had to be shown was that the accused authored or published the words, that the alleged innuendo was established, and that the words were in fact libellous. Whether the material was libellous was a matter for the Court to decide, not the jury.[2]

In a master stroke of advocacy, Andrew Hamilton admitted that Zenger had published the words, thereby eliminating the need for the Attorney General to call witnesses who would no doubt have been prejudicial to Zenger. Hamilton then argued that truth was a defence, implicitly admitting the innuendo. He sought to call witnesses of his own to demonstrate the truth of the words, but the Chief Justice denied the request, ruling that truth was not a defence.

Hamilton then proceeded, courageously, to address the jury directly, in a manner which contradicted the ruling of the youthful Chief Justice.[3] He attacked the rule that truth is not a defence; he argued that the rule was inconsistent with the right of freedom of speech; he said the English rule was not applicable in America where the government is the servant of and answerable to the people; he argued that the jury had the power to decide the law as well as the facts; and he appealed to the cause of liberty:

“It is natural, it is a privilege, I will go farther; it is a right, which all free men claim, that they are entitled to complain when they are hurt. They have a right publicly to remonstrate against the abuses of power in the strongest terms, to put their neighbors upon their guard against the craft or open violence of men in authority, and to assert with courage the sense they have of the blessings of liberty, the value they put upon it, and their resolution at all hazards to preserve it as one of the greatest blessings heaven can bestow…

The question before the Court and you, gentlemen of the jury, is not of small or private concern, it is not the cause of a poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying: No! It may in its consequence affect every Freeman that lives under a British government on the main of America. It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty … That to which nature and the laws of our country have given us a right – the liberty – both of exposing and opposing arbitrary power … by speaking and writing truth.”

Chief Justice De Lancey instructed the jury that, as publication was admitted, the only matter which should come before them was whether the publication was a libel, which was a matter of law which they may leave to the Court. The summing up, whilst technically leaving the matter to the jury, effectively directed the jury that the publication was libellous.

It did not take long for the jury to return a verdict of not guilty.

The verdict was met with great acclaim in and outside the courtroom.

Reports of the Zenger trial spread throughout America and England.[4] The trial was said to have “made a great noise in the world”.[5] Zenger also published a report of the proceedings in pamphlet form in June 1736, written by James Alexander. It was re-published numerous times as late as 1765 and 1770 and (including in England) in 1784.[6] That report was reprinted in Volume 17 of Howell’s State Trials reports published in England in the early nineteenth century.

There are two main areas in which Zenger’s Case has had an impact: trial by jury; and freedom of speech and of the press.

Trial by Jury

First, Zenger was a stark example of the importance of the jury in providing a constitutional check on executive power. It was an instance of jury nullification – that is where a jury acts contrary to the instructions of the judge as to the law, to prevent an unfair result.

So concerned was King George III about jury nullification that, in the 1765 Stamp Act, violators were exposed to trial in the Vice Admiralty court without juries and which could be held anywhere in the British empire. And British Parliament tried again to undermine trial by jury in the so-called Intolerable Acts of 1774. By those Acts, Massachusetts county sheriffs (appointed by the Governor) were empowered to appoint juries directly, and the Massachusetts Governor could transfer trials to Great Britain or elsewhere.

It is not surprising then that trial by jury featured in the Declaration of Independence, and was guaranteed by Article III of the Constitution, and in the Sixth and Seventh Amendments.

And, as Sir Owen Dixon recognised, the Australian Constitution was “framed after the pattern of that of the United States”, the framers having studied it with great care.[7]

The reader is invited to consider the similarities between the last paragraph of Article III § 2 of the United States Constitution and s 80 of the Australian Constitution:

“… The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.” (Art III §2)

“The trial on indictment of any offence against any law of the Commonwealth shall be by jury, and every such trial shall be held in the State where the offence was committed, and if the offence was not committed within any State the trial shall be held at such place or places as the Parliament prescribes.” (s 80)

In the writer’s view, it would be wrong to say that the United States Constitution played no role in relation to the inclusion of s 80 in the Australian Constitution.

Freedom of speech/the press

Second, as Professor Levy – the Zenger sceptic – has conceded, “the verdict of history is correct in regarding [Zenger] as a watershed in the evolution of freedom of the press, not because it set a legal precedent, for it set none, but because the jury’s verdict resonated with popular opinion”.[8]

As another commentator put it, “the Zenger case, though it did not directly ensure the freedom of the press, it prefigured that revolution ‘in the hearts and minds of the people’ which was to make an ideal of 1735 an American reality, and it has served repeatedly to remind Americans of the debt free men owe to free speech”.[9]

Because of Zenger, newspapers were emboldened to criticise the policies of King George III; concerns about jury nullification discouraged prosecutions.[10]

In the ensuing years, as the controversy with Great Britain was played out in the press, Zenger was from time to time relied on by those who advocated the right to criticise the policies of King George III and royalist controlled Assemblies.[11]

And though records were not always kept, there are examples of Zenger being mentioned during the debates for ratification of what became known as the Bill of Rights.[12]

Accordingly Zenger led the way for the First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech and of the press in the United States.

The First Amendment provides:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

In terms of Australian law, the High Court of Australia was aware of the First and Fourteenth Amendments when in the 1990s it recognised an implied freedom of political communication in the Australian Constitution.

At another level, the First and Fourteenth Amendments also played a role in the evolution of the law of sedition.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, it became generally accepted that mere political criticism in good faith and for justifiable ends was not criminal, and truth was relevant evidence for that purpose.

That was the argument made by Alexander Hamilton in People v Croswell, 3 Johns. Cas. 336 (NY 1804), along with the submission that juries were entitled to give a general verdict. That argument was accepted by Chancellor Kent (in the statutory minority). Kent J’s opinion was widely circulated and was acted upon by the New York legislature in 1805[13] and by other States soon after.[14]

However, the writer has found no English case citing Croswell or the New York statute of 1805.

In any event, in 1792, Fox’s Libel Act was enacted in the United Kingdom.[15] By that Act, it was made the province of the jury to give a general verdict of guilt or innocence in criminal libel cases, including whether the offending material was libellous.

Sir Fitzjames Stephen has attributed to Fox’s Libel Act the shift in English law to making malicious intent a necessary element to be shown in seditious libel.[16]

However that may be, it is hard to overlook the significance of the fact that Fox’s Libel Act received Royal Assent on 15 June 1792, a mere matter of months after ratification of the First Amendment on 15 December 1791. The passage of that Amendment must be taken to have been widely known in legal circles in the United Kingdom.

Incidentally, the First Amendment came into force on ratification by the eleventh State, Virginia, whose Constitution allowed truth to be given as a defence and juries to give general verdicts in seditious libel prosecutions.[18]

Then in the year 1899, Sir Samuel Griffith’s Queensland Criminal Code was enacted. This enacted a sedition offence in ss 44-46 and 52 based on the premise that mere political criticism in good faith for justifiable ends was not criminal. For example, it was an offence to use words with the intention of bringing the Sovereign into hatred or contempt or of exciting disaffection against the Sovereign or Government or Constitution of Queensland, unless done in good faith for one or more enumerated purposes, including to endeavour to show that the Sovereign has been mistaken in any of her Counsels or to point out errors or defects in the Government of Queensland.

To like effect, similar sedition offences were provided for in ss 24A to 24D of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), added in 1920,[19] and in Australian Code jurisdictions.

These sedition offences were modelled off the work of Sir Fitzjames Stephen in England.[20] Sir Samuel Griffith adopted Sir Fitzjames Stephen’s Article 93 in his Digest of Criminal Law, 3rd ed 1883 (London: MacMillan) and section 102 of the draft English Criminal Code of 1880 of which Sir Fitzjames Stephen was one of the drafters.[21] But he was fully aware of Zenger’s Case: in 1883, in another publication, Stephen cited Zenger’s Case, describing it as “remarkable”.[22]

The law of sedition has since moved on even further.

The United States Supreme Court eventually (after some roadblocks along the way) came to accept that mere words critical of government cannot, under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, be punishable as seditious libel, whether the words were true or not, and whether they were published in good faith or not. Words could amount to sedition, but the speech had to be intended to result in a crime and there had to be a “clear and present danger” that it actually will result in a crime, as held in Schenck v United States in 1919.[23] That test was reformulated in 1969 by the requirement that the words be directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and be likely to incite or produce such action.[24]

Dixon J cited Schenck v United States in his dissent in Burns v Ransley in 1949.[25]

The statutory majority in Burns v Ransley and the majority in another 1949 High Court decision, R v Sharkey,[26] show that Australian law had not at that time advanced to the point reached by the United States Supreme Court. In Burns v Ransley and R v Sharkey, it was held that the offence of sedition under the then Crimes Act 1914 could be committed whenever the accused had an intention to excite disaffection against the government or the Constitution even if there was no intention to excite imminent violence or an illegal act.[27]

However, in 2005, ss 24A to 24D of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) were repealed and replaced with new sedition offences inserted into the Criminal Code 1995 (Cth).[28] These provisions were further amended in 2011.[29]

Under those new provisions, mere words critical of government are not seditious. A person has to, for example, intentionally urge another to overthrow the Constitution or Government by force or violence intending that such force or violence will occur.[30]

The implications of those two 1949 High Court cases remain to be reconsidered in the light of the implied freedom of political communication. This remains a live issue as sections 44-46 and 52 of the Qld Criminal Code are still in force. The common law of sedition applies in non-Code States.

But the present point is that the 2005/2011 Commonwealth amendments were likely influenced by the First and Fourteenth Amendments or at least by the implied freedom of political communication. The Gibbs committee, whose recommendations were adopted in the federal changes in 2005, said that the changes were needed “to accord with a modern democratic society”.[31] Sir Harry Gibbs, who chaired the Commission, would have been aware of the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

In any event, the implied freedom of political communication which was discussed in the Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee enquiry into the Anti-Terrorism (No 2) Bill 2005.[32]

The Australian Law Reform Commission, in its 2006 report “Fighting Words”, made several references to US law.[33]

Conclusion

At the time the First Congress of the United States debated what would become the Bill of Rights, Governeur Morris, a Founding Father and descendant of Morris CJ, described the Zenger case as “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionalized America”.[34]

In the writer’s opinion, the impact of Zenger’s Case is not limited to American law. The ripple effect of Zenger has also been felt in Anglo-Australian law.

[1] The following background and case summary draws on R v Zenger (1735) 17 State Trials 675; and E Moglen, “Considering Zenger: Partisan Politics and the Legal Profession in Provincial New York”, 94 Colum L Rev 1495 (1994). The report in State Trials had been previously published in pamphlet form by Zenger himself, reputed to have been written by James Alexander. That version is available at history.nycourts.gov/case/crown-v-zenger.

[2] See Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England, vol 2 pp 298-395 (London: MacMillan and Co 1883). See the reference to Zenger at p323 n4. See also “Fighting Words: A Review of Sedition Laws in Australia”, ALRC 104 at pp49-51.

[3] James Alexander is reputed to be the mastermind behind Andrew Hamilton’s argument.

[4] Katz, Introduction to J. Alexander: A Brief Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, (S Katz ed 1963) p 26, 30; Alison Olsen, “The Zenger Case Revisited: Satire, Sedition and Political Debate in Eighteenth Century America”, (2000) 35:3 Early American Literature 223, 238; Livingston Rutherford, John Peter Zenger: His Press, His Trial and a Bibliography of Zenger Imprints (1904) p 128; Levy, Emergence of a Free Press, 44 (Ivan R Dee Chicago 1985)

[5] (1735) 17 State Trials 675, at p675.

[6] Olsen, p238; Levy, pp77, 156.

[7] Dixon, “Two Constitutions Compared” in Jesting Pilate (Law Book Co 1965) at p101.

[8] Levy, 37.

[9] Katz, Introduction to J. Alexander: A Brief Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, (S Katz ed 1963) p 35.

[10] Alison Olsen, “The Zenger Case Revisited: Satire, Sedition and Political Debate in Eighteenth Century America”, (2000) 35:3 Early American Literature 223; Levy, 17.

[11] Levy, 62, 69, Professor Douglas O. Lindner, “The Trial of John Peter Zenger and the Birth of Freedom of the Press” p8, published in Historians on America, at usinfo.org/zhtw/DOCS/historians-on-america.

[12] Levy, 244, 246.

[13] See Sess. 28, c. 90 (6 April 1805), noted in the report of The People v Croswell, 3 Johns. Cas 337, 411-2 (NY 1804).

[14] Garrison v Louisiana, 379 US 64 (1964) at p 72.

[15] 32 George III, c 60.

[16] Stephen, History of the Criminal Law of England, vol 2 p359 (1883). As for Australian law, that shift in English law was reflected in the common law received by the Australian colonies: see eg R v Henry Seekamp, Supreme Court of Victoria, unreported, The Argus (Melbourne) 24 January 1855 p4, The Argus 6 February 1855 p5 and The Age 27 March 1855 p5.

[18] Levy, pp211-2.

[19] War Precautions Repeal Act 1920 (Cth), s12, adding ss 24A to 24D to the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth).

[20] See Burns v Ransley (1949) 79 CLR 101 per Dixon J at p 115; O’Regan, “Sir Samuel Griffith’s Criminal Code” (1991) 14:8 Royal Historical Society of Queensland Journal 305, 307.

[21] Section 102 is set out in full in Boucher v The King [1951] SCR 265, 306.

[22] See Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England, vol 2 p 323 n4 (London: MacMillan and Co 1883). Stephen had read the summary of the Zenger trial written allegedly by Alexander Hamilton.

[23] Schenk v United States, 249 US 47 (1919) at p52.

[24] Brandenburg v Ohio, 395 US 444 (1969), replacing the previous “clear and present danger” test articulated by Holmes J in Schenck v United States, 249 US 47 at p52 (1919). It is not necessary to enter the debate about whether the Framers intended the First Amendment to have the operation that it was later interpreted to have.

[25] Burns v Ransley (1949) 79 CLR 101, at p117, citing Schenk v United States, 249 US 47 at p52.

[26] R v Sharkey (1949) 79 CLR 121. R v Sharkey (1949) 79 CLR 121

[27] Burns v Ransley (1949) 79 CLR 101; R v Sharkey (1949) 79 CLR 121.

[28] See Schedule 7 of the Anti-Terrorism Act (No.2) 2005 (Cth).

[29] National Security Legislation Amendment Act 2010, Schedule 1, taking effect on 19 September 2011.

[30] Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), Schedule, s 80.2. Similarly, under the post-911 terrorism provisions of the Criminal Code, a person does not engage in a “terrorist act” by mere advocacy if not intended to cause death or serious harm that is physical harm to a person, or to endanger the life of another person or to create a serious risk to the health or safety of a section of the public. Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), Schedule, ss 100.1, 101.1.

[31] H. Gibbs, R. Watson and A Menzies, Review of Commonwealth Criminal Law, Fifth Interim Report (1991) at [32.13].

[32] ALRC 104 at [7.13].

[33] ALRC 104 at [2.36], [6.31], [8.71]-[8.72].

[34] See history.nycourts.gov/case/crown-v-zenger/

Many excellent articles and presentations have been written or given touching upon Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562. The attention so given is entirely appropriate. The decision, especially Lord Atkin’s judgment, has been cited on countless occasions and has had a profound influence on Anglo-Australian law. But it is also worthwhile to spare a moment to reflect on a decision cited by the House of Lords in Donoghue v Stevenson, and the Judge behind that decision. The decision was MacPherson v Buick Motor Co, 217 NY 382, 111 NE 1050 (NY 1916), and the Judge behind it was Justice Benjamin N Cardozo.

In MacPherson v Buick Motor Co, it was held by the influential New York Court of Appeals in 1916 that a manufacturer of an automobile owed a duty of care in tort to a consumer injured whilst driving the vehicle, notwithstanding the absence of privity of contract.

First, a little about the man, Benjamin Cardozo.

Life and career of Cardozo J

Benjamin Nathan Cardozo, of Sephardic Jewish/Spanish-Portuguese heritage, was born in New York City on 24 May 1870 to Rebecca Nathan and Albert Cardozo. He had a twin sister, and they had four other siblings. His grandfather had been nominated a Justice of the New York Supreme Court, but died before he took office. Benjamin Cardozo’s own father was in fact a New York Supreme Court Justice, but he resigned amidst a judicial corruption scandal. This had a profound effect on Benjamin, who was determined to restore his family’s name.

Benjamin’s mother died in 1879, when he was still quite young.

At age 15, Cardozo attended Columbia College, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree followed by a Master’s in Political Science. Then, in 1889, he attended Columbia Law School. He was by all accounts a brilliant student. After two years there, he passed the New York Bar exam in 1891 and began practising law in New York City alongside his brother. He remained in practice with Simpson, Warren and Cardozo until 1913. He gained an esteemed reputation in commercial law.

In 1913, having practised for about 23 years, Cardozo was elected to a 14 year term on the New York Supreme Court, due to start on 1 January 1914. But in February 1914, he was appointed as a temporary Judge on the New York Court of Appeals, the State’s highest court. In 1917, Cardozo J became a permanent member of the Court of Appeals. In 1926, he was elected to a 14 year term as Chief Judge of that Court.

After having served 18 years on the Court of Appeals, Cardozo CJ resigned in 1932 to take up an appointment as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Even though he was a Democrat, he was appointed by the Republican President, Herbert Hoover. His appointment was met with universal acclaim. The Senate confirmed his appointment by a unanimous vote.

Cardozo J was on the US Supreme Court for six years, supporting a number of Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives, as a member of the so-called “Three Musketeers” along with Justices Brandeis and Stone.

He suffered a heart attack in 1937 and a stroke in 1938. He passed away, aged 68, on 9 July 1938, in Port Chester, Rye, New York State.

He had never married. He was a modest man of high principles, loved by his colleagues.

In addition to his many influential judicial decisions, he was a prolific extra-judicial writer. Amongst other works, he is particularly renowned for his work “Nature of the Judicial Process” (1921), designed for judges but which is standard reading for American law students.

MacPherson v Buick Motor Co

Donald MacPherson’s 1911 Buick collapsed on the road to Saratoga Springs when he was driving just 8 miles per hour. He was thrown out and injured. One of the wheels contained defective wood, and the spokes had “crumbled into fragments”. Mr MacPherson had bought the Buick from a retailer. The retailer had bought the car from Buick Motor Co. Buick Motor Co was the manufacturer of the vehicle, though it had purchased the wheel as a component part from Imperial Wheel Co of Michigan. There was evidence that the defect could have been discovered by Buick Motor Co had it carried out a reasonable inspection. The Supreme Court held that Buick Motor Co was liable in negligence to Mr MacPherson, which decision was upheld by the Supreme Court Appellate Division. By majority, the Court of Appeals held that the decision of the Appellate Division should be affirmed.

Previously, it had been the rule in New York, based on the English decision of Winterbottom v Wright (1842) 10 M & W, 152 ER 402, that a manufacturer’s liability for negligence only extended to purchasers with whom they were in privity of contract. That English case concerned a horse drawn carriage. The New York cases recognised an exception to that rule, where the product was “inherently dangerous”, the leading example of which was a case concerning poison which had been wrongly labelled as dandelion extract: Thomas v Winchester, 6 NY 397 (NY 1852). But as the trial judge had summed up to the jury in MacPherson v Buick, “an automobile is not an inherently dangerous vehicle”. The then Chief Judge also noted in dissent that an automobile moving at only 8 miles an hour “was not any more dangerous to the occupants of the car than a similarly defective wheel would be to the occupants of a carriage drawn by a horse at the same speed”.

In MacPherson v Buick, however, Cardozo J, in delivering the leading judgment, closely analysed the cases said to be authority for the exception, pointing out the inconsistencies and uncertainties to which the exception gave rise, and the illogicality of the distinction between products inherently dangerous and those which were dangerous because of negligent construction. He also referred to the need of the law to keep a-pace with developing technology. He considered that what those earlier cases in fact decided needed to be re-visited. He said:

“The question to be determined is whether the defendant owed a duty of care and vigilance to any one but the immediate purchaser… We hold, then, that the principle of Thomas v Winchester is not limited to poisons, explosives, and things of like nature, to things which in their normal operation are implements of destruction. If the nature of a thing is such that it is reasonably certain to place life and limb in peril when negligently made, it is then a thing of danger. Its nature gives warning of the consequences to be expected. If to the element of danger there is added knowledge that the thing will be used without new tests, then, irrespective of contract, the manufacturer of this thing of danger is under a duty to make it carefully. That is as far as we are required to go for the decision of this case. There must be knowledge of a danger, not merely possible, but probable… There must also be knowledge that in the usual course of events the danger will be shared by others than the buyer… If he is negligent, where danger is foreseen, a liability will follow.”

His Honour found those factual matters to be made out in that case. Cardozo J observed, “The dealer was indeed the one person of whom it might be said with some approach to certainty that, by him the car would not be used.” He noted more generally that “it is possible that even knowledge of the danger and of the use will not always be enough. The proximity or remoteness of the relation is a factor to be considered.” But proximity or remoteness were not a problem in the instant case when the above mentioned factors were present.

These pronouncements do not seem all that remarkable to the modern day Anglo-Australian lawyer.

Donoghue v Stevenson

It is not surprising that MacPherson v Buick should have been referred to, and cited by, the House of Lords. MacPherson v Buick was the first common law case dealing with the product liability owed to a consumer by a manufacturer of mass produced products and upholding a duty of care in negligence.

Lord Atkin had this to say (at pages 598-9):

“It is always a satisfaction to an English lawyer to be able to test his application of fundamental principles of the common law by the development of the same doctrines by the lawyers of the Courts of the United States. In that country I find that the law appears to be well established in the sense in which I have indicated. The mouse had emerged from the ginger-beer bottle in the United States before it appeared in Scotland, but there it brought a liability upon the manufacturer. I must not in this long judgment do more than refer to the illuminating judgment of Cardozo J in MacPherson v Buick Motor Co in the New York Court of Appeals, in which he states the principles of the law as I should desire to state them, and reviews the authorities in other States than his own. Whether the principle he affirms would apply to the particular facts of that case in this country would be a question for consideration if the case arose. It might be that the course of business, by giving opportunities of examination to the immediate purchaser or otherwise, prevented the relation between manufacturer and the user of the car being so close as to create a duty. But the American decision would undoubtedly lead to a decision in favour of the pursuer in the present case.”

This was high praise indeed.

The qualification by Lord Atkin in the penultimate sentences in that paragraph was unnecessary, because Cardozo J indicated at several points in his judgment, that the principle would not apply if there was, and was known to be, a reasonable opportunity for intermediate examination or examination before use.

Lord Atkin then continued to state the principle as it applied to English and Scots law (at page 599):

“… a manufacturer of products, which he sells in such a form as to show that he intends them to reach the ultimate consumer in the form in which they left him with no reasonable possibility of intermediate examination, and with the knowledge that the absence of reasonable care in the preparation or putting up of the products will result in an injury to the consumer’s life or property, owes a duty to the consumer to take that reasonable care”.

This was masterful in its reduction of the principle to one sentence.

Even if Lord Atkin only “drew support for his own approach” [1] from MacPherson v Buick, the latter decision still had an influence on the result as is evident from Lord Atkin’s glowing praise.

Of course, there is much more to Lord Atkin’s speech than a statement of and upholding of the principle of a manufacturer’s product liability to a consumer. It has been pointed out there are similarities between Lord Atkin’s neighbour principle and the judgment of Cardozo CJ in the case of Palsgraf v Long Island Railway Co, 248 NY 339 (1928). [2] But it is unlikely Lord Atkin was aware of that case, as Palsgraf was evidently not cited in argument, and it is not referred to in any of the judgments, in Donoghue v Stevenson.

Moving on to other Law Lords, the above passage from Cardozo J’s judgment was set out by Lord MacMillan (one of the other majority Judges in Donoghue v Stevenson) at [1932] AC 562, 617-8. That also speaks volumes.

Lord Buckmaster, in dissent in Donoghue v Stevenson, distinguished MacPherson v Buick on the basis that it was a decision that “a motor-car might reasonably be regarded as a dangerous article”: [1932] AC 562, 577. Lords Atkin and MacMillan did not agree with that interpretation of MacPherson v Buick, with Lord Atkin referring (as had Cardozo J) to the illogicality of the distinction between a thing dangerous in itself, and a thing which becomes dangerous by negligent construction (see pages 595-6 of [1932] AC). The fact that Lord Buckmaster felt the need to distinguish a decision from another jurisdiction is testament to the force of its reasoning.

Whether Cardozo J expanded the exception in Thomas v Winchester or laid down a new principle altogether does not matter. They are one and the same thing as a matter of practice. Cardozo J so expanded the “exception” to the point where the privity rule, if not “cut out and extirpated altogether”, was “left with the shadow of continued life, but sterilized, truncated, impotent for harm”: Nature of the Judicial Process, pp98-9.

Cardozo J’s legacy

What is remarkable about MacPherson v Buick Motor Co is not only the significance of what it decided, and the fact that it was the first case to so decide. It is also the fact that it was decided in 1916 barely two years after Cardozo J’s appointment to the Court of Appeals, whilst he was still a temporary judge, and the fact that it was a majority decision, in which Cardozo J’s judgment was given notwithstanding the strong dissent of the then Chief Judge, Willard Bartlett.

Indeed, Cardozo J’s boldness and eloquent writing style are amongst the reasons why Cardozo J/CJ’s judgments have had such a profound effect, not only in the United States but also elsewhere.

MacPherson v Buick is not the only occasion where the judgments of Cardozo J/CJ are cited by Anglo-Australian courts. An austlii search of “Cardozo” in the High Court of Australia directory alone produced a staggering 100 results, including his decisions from a wide range of contexts, as well as his extra-judicial writings.

A few of the more well known examples however are:

-

Wood v Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon , 222 N.Y. 88; 118 N.E. 214 (N.Y. 1917) (“The law has outgrown its primitive stage of formalism when the precise word was the sovereign talisman, and every slip was fatal. It takes a broader view to-day. A promise may be lacking, and yet the whole writing may be ‘instinct with an obligation,’ imperfectly expressed. If that is so, there is a contract”);

- Loucks v Standard Oil, 120 NE 198, 201 (NY 1918) (“The courts are not free to refuse to enforce a foreign right at the pleasure of the judges, to suit the individual notion of expediency or fairness. They do not close their doors, unless help would violate some fundamental principle of justice, some prevalent conception of good morals, some deep-rooted tradition of the common weal”);

- Beatty v Guggenheim, 225 NY 380 (NY 1919) (“A constructive trust is the formula through which the conscience of equity finds expression. When property has been acquired in such circumstances that the holder of the legal title may not in good conscience retain the beneficial interest, equity converts him into a trustee”);

- Wagner v International Ry Co, 133 NE 437 (NY 1921) (“Danger invites rescue”);

- Meinhard v Salmon, 249 NY 458, 164 NE 545 (NY 1928) (“A trustee is held to something stricter than the morals of the market place. Not honesty alone, but the punctilio of an honor the most sensitive, is then the standard of behaviour … the level of conduct for fiduciaries [has] been kept at a higher level than that trodden by the crowd”);

- Ultramares Corp v Touche, 174 NE 441 (NY 1932) (no duty of care where it would lead to “a liability in an indeterminate amount for an indeterminate time to an indeterminate class”);

- Baldwin v GAF Selig Inc, 294 US 511 (1935) (“The Constitution was framed under the dominion of a political philosophy less parochial in range. It was framed upon the theory that the peoples of the several states must sink or swim together, and that in the long run prosperity and salvation are in union and not division”);

- Palko v Connecticut, 302 US 319 (1937) (freedom of speech is “the matrix, the indispensable condition, of nearly every other form of freedom”).

As Lord Atkin shows us all by his example, we should not be reluctant to look to American authorities where relevant. There are many instances where Anglo-Australian law has been influenced by American law, and there is no reason why this should not continue to be so. This is not only at the common law level, but also at the statutory (including constitutional) level. For example, it is not widely known that the Judicature Acts 1873-1875 were influenced by the “Field” Code of Civil Procedure (NY) of 1848, which abolished the forms of action as well as the procedural distinction between suits in equity and actions at law. That followed upon the abolition of the Court of Chancery as a separate court in New York State in 1846. The Field Code preceded the Common Law Procedure Act of 1852.

The above is not to say that cross fertilisation is a one way street. Nor is it to say that we should always reach the same conclusions. But the way American lawyers have grappled with similar problems means that their jurisprudence has been and can continue to be of assistance in resolving disputes according to our own standards. As Cardozo J himself observed in Loucks v Standard Oil, 120 NE 198, 201 (NY 1918), “We are not so provincial as to say that every solution of a problem is wrong because we deal with it otherwise at home”.

Dr Stephen Lee, Barrister

[1] Chapman, The Snail and the Ginger Beer: The singular case of Donoghue v Stevenson, Wildy, Simmonds & Hill, 2010, p42.

[2] Knapp, International Encyclopaedia of Comparative Law (Martinus Nijhoff 1983), p71.

Introduction

John Jay is regarded as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States of America. There, he is well known as Statesman and first Chief Justice of the United States. In Australia, we know relatively little about him, compared to other American Statesmen and judges. John Jay did leave an enduring judicial legacy, including for Australian law. It is worth exploring that legacy in these pages.

Background

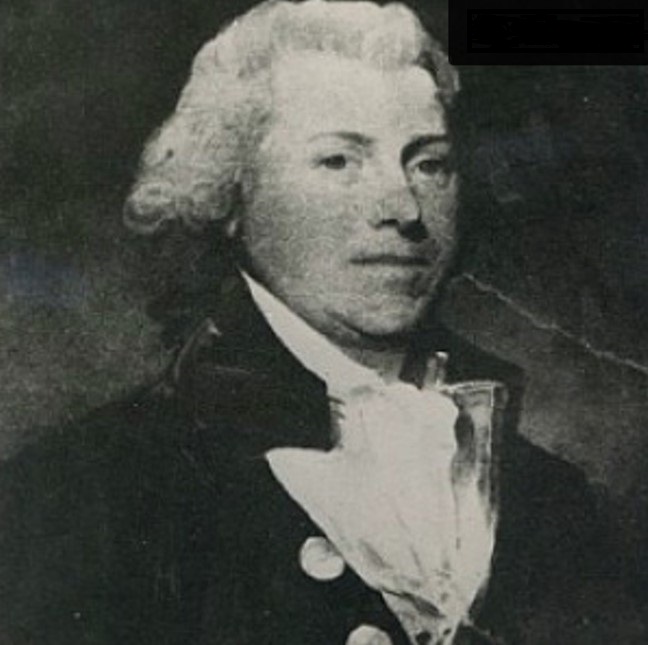

John Jay was born in Manhattan, New York City on 12 December 1745.[1] He was of French Huguenot and Dutch heritage. The son of a wealthy merchant, he grew up on the family farm in Rye, New York. He went to a grammar school at New Rochelle, where his studies included French. From 1760 to 1764, he went to King’s (now Columbia) College and there received a classical education.

Jay’s childhood home in Rye, New York

He determined on a career in law. To this end, he began by studying Grotius. Two weeks after graduating from College, he was apprenticed to barrister Benjamin Kissen.

In 1768 he was admitted to the New York Bar, and formed a partnership with Robert R Livingston Jr.[2] He built up a substantial and successful practice and became known for his brilliant oratory.[3]

In 1774, he was elected one of the New York delegates to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In 1775 he was also a New York delegate to the Second Continental Congress, which body adopted the Articles of Confederation in 1777. He did not sign the Declaration of Independence of 4 July 1776 because he had also been appointed delegate of the New York Provincial Assembly in April of that year, which refused to allow him leave of absence to travel to Philadelphia. But he proposed the resolution at the New York Provincial Assembly that the Declaration of Independence be adopted by New York State.

John Jay played a pivotal role in drafting the New York Constitution, which was adopted by the New York Provincial Assembly in 1777. He was immediately appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature of New York established under the said New York Constitution, which was intended to continue, or replace, the Colonial Supreme Court which had been in existence since 1691. However, within British lines Judge Ludlow also continued to sit as judge of that latter body.

Minimal records have survived of his work as state Chief Justice.[4] Jay CJ’s work on that Court was interrupted when the New York legislature resolved that he be appointed to make representations to the Continental Congress on the settlement of a dispute between New York and the region which was to become Vermont. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed President of the Congress.

John Jay resigned as Chief Justice on 10 August 1779, thereby making himself available to serve in that and other capacities.

In 1779, he was appointed Minister to Spain, where he lobbied for diplomatic recognition and monetary support for the war. He occupied this role until 1782, when he was appointed Commissioner to treat with Great Britain to negotiate for peace. He spent several years in France and amongst other things played an integral role in the multi-party negotiations which led to the Treaty of Paris (1783), which officially ended the Revolutionary War. The treaty was well received at home.[5]

John Jay returned to New York City in 1784, and was appointed Secretary for Foreign Affairs.

John Jay was not a delegate to the Constitutional Convention which met in May 1787 in Philadelphia, because some voted against him on account of his known federalist views. But the drafters of the United States Constitution had before them John Jay’s New York Constitution. And he was a leading member of the New York Convention which ratified the United States Constitution in July 1788.

Further, between October 1787 and June 1788 a series of essays were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay and published in New York newspapers, anonymously, under the pseudonym “Publius”. They advocated the federalist case. The essays were also collected and published in two volumes as the “Federalist”. There were eighty-five essays in all. Most were authored by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Mr Jay wrote five. He might have played a larger role in that regard but for an injury – a stone had been thrown at his head at a riot which Mr Jay was trying to quell.

It has been said that “The essays became, for supporters, a Federalist bible” and “Perhaps no other single document best speaks in detail to the intention of the framers behind many of the concepts underlying the federal constitution”.[6]

As soon as he recovered from his injury, John Jay also published, anonymously, an “Address to the People of New York”, distributed in pamphlet form,[7] which advocated the Federalist case.

On 26 September 1789, President Washington appointed John Jay first Chief Justice of the United States, and he was confirmed, without objection, by the Senate.

In that role, he and Associate Justices also sat on federal Circuit Courts. The obligation of “riding circuit” was time consuming and burdensome. In those days travel was by horse drawn carriage, and Justices were required, since 1792, to rotate between Circuits, including Circuits that did not include their home States.[8]

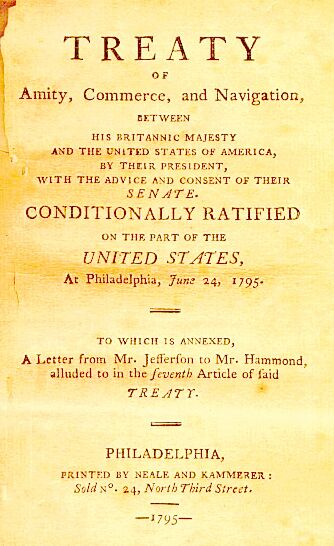

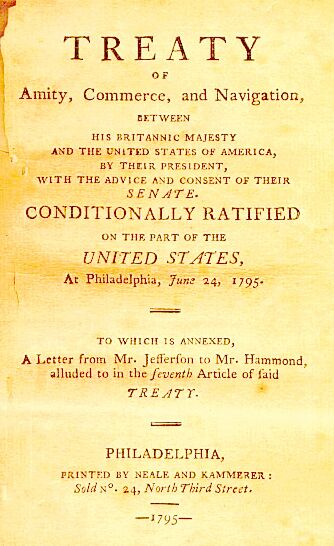

His judicial duties were interrupted by being called to serve as special envoy to Great Britain in 1794. He negotiated a treaty (commonly referred to since as the “Jay Treaty”) to settle issues remaining since the Treaty of Paris. The Treaty was ratified by the Senate in 1795. Despite that, it was not generally received well and, it is said, “very possibly” cost him the Presidency.[9]

The Jay Treaty

Mr Jay resigned as Chief Justice of the United States in 1795. He had been elected Governor of the State of New York. He was re-elected as Governor three years later. During his tenure, he played a pivotal role in the passage of an Emancipation Act in 1799 which law “set in motion the gradual ending of slavery within the state over a period of years”.[10] He did not stand in 1801 for a further term, and he retired from public life.

He declined an offer to nominate him for a second term as Chief Justice of the United States. John Marshall was nominated in his stead.[11]

Mr Jay died peacefully at Bedford, New York, on 17 May 1829, at the age of 83.

Jurist

In assessing the impact of Jay CJ as a jurist, it is not to be forgotten that his time as Chief Justice of the United States, like his time as New York Chief Justice, was interrupted by being called to serve in other ways including those mentioned above. That is not to say that his judicial output was insubstantial numerically – it was not.[12] It is not intended in this paper, nor is it feasible, to conduct a wide-ranging survey of the decisions of Jay CJ, whether sitting in the state or federal Supreme Courts or on circuit. But there are nevertheless some opinions of his which should be singled out as having had a particular impact in Australia.

…some opinions of his [Jay CJ] which should be singled out as having had a particular impact in Australia.

War Pensions

In 1792, the United States Congress enacted the Invalid Pensions Act which provided for pensions for war veterans who were placed on an approved pension list.[13] The Act conferred a jurisdiction on the Circuit Courts to decide if applicants should be placed on that list, which decision was reviewable by the Secretary of War and Congress.

On about 5 April 1792,[14] the Circuit Court for the District of New York, consisting of Jay CJ, Cushing J and Duane District Judge, unanimously agreed:[15]

“That by the constitution of the United States, the government thereof is divided into three distinct and independent branches, and that it is the duty of each to abstain from, and to oppose, encroachments on either. That neither the legislative nor the executive branches, can constitutionally assign to the judicial any duties, but such as are properly judicial, and to be performed in a judicial manner. That the duties assigned to the circuit, by this act, are not of that description, and that the act itself does not appear to contemplate them as such; inasmuch as it subjects the decisions of these courts, made pursuant to those duties, first to the consideration of and suspension of the secretary of war, and then to the revision of the legislature; whereas, by the constitution, neither the secretary of war, nor any other executive officer, nor even the legislature, are authorized to sit as a court of errors on the judicial acts or opinions of this court…”

They went on to consider whether they could act in persona designata.

Their Honours asked the Clerk of the Court to write to the President enclosing a copy of their observations, requesting that it be passed on to Congress. Subsequently, Jay CJ and Cushing J held the Circuit Courts for the Districts of Connecticut, Rhode Island and Vermont, together with the District Judges, and gave a similar opinion.

Thereafter, in April and June of 1792, Justices Wilson, Blair and Iredell et al made similar representations to the President, acting in the name of the Circuit Courts for the Districts of Pennsylvania and North Carolina, respectively.[16] Different views were expressed on whether the members of the Court could act in persona designata.

In August 1792, in Hayburn’s case, a motion came on before the Supreme Court of the United States for mandamus directed to the Circuit Court for the District of Pennsylvania compelling it to proceed in a certain petition for an invalid pension for William Hayburn. After hearing argument on the merits, the Court, Jay CJ presiding, adjourned the Court until the next term (February 1793). In the meantime, in February 1793 before the Court reconvened, Congress repealed and replaced the provisions considered unconstitutional, and otherwise provided for the relief of the pensioners.[17] No doubt the Court had given Congress that opportunity. The case was then dismissed as being purely academic.

But there had been cases where judges as commissioners had certified pending claims by applicants to be placed on the pension list under the 1792 Act. There was no decided Supreme Court decision that bound all Circuits. The 1793 Act indeed provided in s 3 that:

“But it shall be the duty of the Secretary of War, in conjunction with the Attorney General, to take such measures as may be necessary to obtain an adjudication of the Supreme Court of the United States, on the validity of any such rights claimed under the Act aforesaid, by the determination of certain persons styling themselves commissioners.”

In February 1794, the Supreme Court heard Ex Parte Chandler.[18] There, a veteran had been approved for a pension by the Eastern Circuit, but his name was not included in the pension list. John Chandler applied to the Supreme Court by writ of mandamus to compel the Secretary of War to place his name on the list. The Supreme Court, including Jay CJ, denied the writ by oral decision. There is no record of the reasons. It has been surmised, with some force, that the Court considered that the 1792 Act was unconstitutional and that the approval by the Eastern Circuit of Mr Chandler’s application was accordingly null and void.[19]

Also in February 1794, the Supreme Court, Jay CJ presiding, held that the United States could have restitution of a pension paid under the 1792 Act in an action for moneys had and received.[20]

Marshall CJ discussed the aforesaid events in Marbury v Madison, 5 US 137 (1803). The impact of that case in America and Australia needs no elaboration. In the course of upholding the principle of judicial review,[21] Marshall CJ observed at pp171-2:[22]

“This opinion seems not now, for the first time, to be taken up in this country.

It must be well recollected that in 1792, an act passed, directing the secretary at war to place on the pension list such disabled officers and soldiers as should be reported to him, by the circuit courts, which act, so far as the duty was imposed on the courts, was deemed unconstitutional; but some of the judges, thinking that the law might be executed by them in the character of commissioners, proceeded to act and to report in that character.

The law being deemed unconstitutional at the circuits, was repealed, and a different system established; but the question whether those persons, who had been reported by the judges, as commissioners, were entitled, in consequence of that report, to be placed on the pension list, was a legal question, properly determinable in the courts, although the act of placing such persons on the list was to be performed by the head of a department.

That this question might be properly settled, congress passed an act in February, 1793, making it the duty of the secretary of war, in conjunction with the attorney general, to take such measures, as might be necessary to obtain an adjudication of the supreme court of the United States on the validity of any such rights, claimed under the act aforesaid.

After the passage of this act, a mandamus was moved for, to be directed to the secretary at war, commanding him to place on the pension list, a person stating himself to be on the report of the judges.

There is, therefore, much reason to believe, that this mode of trying the legal right of the complainant, was deemed by the head of a department, and by the highest law officer of the United States, the most proper which could be selected for the purpose.

When the subject was brought before the court the decision was, not that mandamus would not lie to the head of a department, directing him to perform an act, enjoined by law, in the performance of which an individual had a vested interest; but that a mandamus ought not to issue in that case – the decision necessarily to be made if the report of the commissioners did not confer on the applicant a legal right.

The judgment in that case, is understood to have decided the merits of all claims of that description; and the persons on the report of the commissioners found it necessary to pursue the mode prescribed by the law subsequent to that which had been deemed unconstitutional, in order to place themselves on the pension list.

The doctrine, therefore, now advanced, is by no means a novel one.”

It should also be mentioned that the remonstrances of Jay CJ and the other Justices were referred to with approval by Dixon J in the important separation of powers case of Victorian Stevedoring and General Contracting Co Pty Ltd v Dignan (1931) 46 CLR 73 at p90.

The Treaty of Paris, by Benjamin West (1783) (Jay stands farthest to the left). The British delegation refused to pose for the painting, leaving it unfinished.

Chisholm

In 1793, a case came before the United States Supreme Court concerning whether an individual citizen of one State had a right to sue another State in that Court: Chisholm v Georgia, 2 US 419 (1793).

One Robert Farquhar had supplied cloth to the Continental Army in Georgia in 1777, for a price agreed with the authorised agent of the State of Georgia. Chisholm, Farquhar’s executor, sued Georgia invoking the original jurisdiction of the United States Supreme Court but the State of Georgia denied liability, maintaining that Georgia had sovereign immunity from suit.[23] Georgia refused to appear in the Supreme Court other than to demur to the jurisdiction.

By a 4:1 majority, the Court held that the State of Georgia was amenable to suit. The majority comprised Jay CJ, Blair, Wilson and Cushing JJ. Iredell J dissented. Each judge published a separate opinion. Opinions were given in reverse order of seniority, as was the custom at the time.

Article III § 2 of the United States Constitution provided relevantly that:

“The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority; – to all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consols; – to all cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction; – to controversies to which the United States shall be a party; – to controversies between two or more States; between a State and citizens of another State; – between citizens of different States; – between citizens of the same State claiming lands under grants of different States, and between a State, or the citizens thereof, and foreign States, citizens or subjects.

In all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consols, and those in which a State shall be a party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction. In all the other cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction …” (emphasis added)

The reference to “State” first in the sequence before “citizens of another State” supported the view that the Constitution was only referring to cases where the State was plaintiff. This was consistent with the sovereign immunity argument in that the State would thereby consent to the jurisdiction of the Court. This view was consistent inter alia with statements made by Alexander Hamilton in Federalist Paper No. 81.

In rejecting that view, a common rebuttal in the opinions of the majority judges, was that the natural and plain reading of the wording included cases where the State was a defendant, relying on the fact that a State must necessarily be a defendant in the case of a controversy between two States. Jay CJ appealed to ordinary rules of construction, saying for example at p476 that “This extension of power is remedial, because it is to settle controversies. It is therefore, to be construed liberally”; and at p477, “Words are to be understood in their ordinary and common acceptation, and the word party being in common usage, applicable to both Plaintiff and Defendant, we cannot limit it to one of them in the present case”. It would have been easy for the framers to have said otherwise, if that had been their intention. Wilson J[24] remarked, citing Bracton, that it would be superfluous to provide a remedy without a right.

Jay CJ and Wilson J also pointed to other provisions in the Constitution where the exercise of federal legislative and executive power bound the States.

Jay CJ further appealed to the reasons inherent in a federation why the natural meaning should prevail, at p476:

“… in cases where some citizens of one State have demands against all the citizens of another State, the cause of liberty and the rights of men forbid, that the latter should be the sole Judges of the justice due to the [former]…”

He said similarly at p 474:

“Prior to the date of the Constitution, the people had not had any national tribunal to which they could resort for justice; the distribution of justice was then confined to State judicatories, in whose institution and organization the people of the other States had no participation, and over whom they had not the least control. There was then no general Court of appellate jurisdiction, by whom the errors of State Courts, affecting either the nation at large or the citizens of any other State, could be revised and corrected. Each State was obliged to acquiesce in the measure of justice which another State might yield to her, or to her citizens; and that even in cases where State considerations were not always favorable to the most exact measure. There was danger that from this source animosities would in time result; and as the transition from animosities to hostilities was in the history of independent States, a common tribunal for the termination of controversies became desirable, from motives both of justice and of policy.

Prior also to that period, the United States had, by taking a place among the nations of the earth, become amenable to the laws of nations; and it was their interest as well as their duty to provide, that those laws should be respected and obeyed; in their national character and capacity, the United States were responsible to foreign nations for the conduct of each State, relative to the law of nations, and the performance of treaties; and there the inexpediency of referring all such questions to State Courts, and particularly to the Courts of delinquent States became apparent. While all the States were bound to protect each, and the citizens of each, it was highly proper and reasonable, that they should be in a capacity, not only to cause justice to be done to each, and the citizens of each; but also to cause justice to be done by each, and the citizens of each; and that, not by violence and force, but in a stable, sedate and regular course of judicial procedure.”

Jay CJ also challenged the notion that the State of Georgia was a “sovereign State” for all purposes. He said:

“Prior to the revolution … All the people of the country were then, subjects of the King of Great Britain, and owed allegiance to him … They were in strict sense fellow subjects, and in a variety of respects one people. When the Revolution commenced, the patriots did not assert that only the same affinity and social connection subsisted between the people, of the colonies, which subsisted between the people of Gaul, Britain and Spain, while Roman provinces, viz. only that affinity and social connection which result from the mere circumstance of being governed by the same Prince; different ideas prevailed, and gave occasion to the Congress of 1774 and 1775. The Revolution, or rather the Declaration of Independence, found the people already united for general purposes, and at the same time providing for their more domestic concerns by State conventions, and other temporary arrangements. From the crown of Great Britain, the sovereignty of their country passed to the people of it … thirteen sovereignties were considered as emerged from the principles of the Revolution, combined with local convenience and considerations; the people nevertheless continued to consider themselves, in a national point of view, as one people …”

Although he (like Wilson J) advanced a notion of popular sovereignty, the underlying point was that the people were, first and foremost, Americans.

Jay CJ also denied that suability was incompatible with sovereignty, and appealed to general principles of justice and equality, for example:

“The only remnant of objection therefore that remains is, that the State is not bound to appear and answer as a Defendant at the suit of an individual: but why it is unreasonable that she should be so bound is hard to conjecture. That rule is said to be a bad one, which does not work both ways…”

And that:

“[The decision of the Court] provides for doing justice without respect of persons, and by securing individual citizens, as well as States, in their respective rights, performs the promise which every free Government makes to every free citizen, of equal justice and protection…”

Portrait of John Jay by Gilbert Stuart, 1794

The Court held that default judgment should be entered against the State of Georgia. But the judgment was not enforced.[25] Georgia passed legislation making it an offence to enforce the judgment, or bring similar claims against the State, punishable by death. This stalemate might be thought to reinforce the point made by Jay CJ about the need for an independent national tribunal with power to quell controversies between States, or between a State and a citizen of another State.

Ultimately, the Eleventh Amendment was passed, ratified in 1795. It provided that:

“The judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by citizens of another State, or by citizens or subjects of any foreign State.”

The United States Supreme Court has since rejected the reasoning in Chisholm, by a 5:4 majority, subject to a vigorous dissent.[26]

But much of the reasoning in Chisholm remains apposite to our own federation.

During the nineteenth century, Chisholm entered the Australian legal lexicon.

Chancellor Kent discussed Chisholm in the first volume of his renowned Commentaries on American Law published in 1826.[27]

Chisholm was referred to by Sir Isaac Isaacs at the Melbourne Convention in 1898.[28]

In their celebrated 1901 work, Quick and Garran referred to Chisolm in their discussion of s 75(iv) of the Australian Constitution.[29]

Sections 75 and 76 of the Australian Constitution provide:

“75. Original jurisdiction of High Court

In all matters:

- arising under any treaty;

- affecting consuls or other representatives of other countries;

- in which the Commonwealth, or a person suing or being sued on behalf of the Commonwealth, is a party;

- between States, or between residents of different States, or between a State and a resident of another State;

- in which a writ of Mandamus or prohibition or an injunction is sought against an officer of the Commonwealth;

the High Court shall have original jurisdiction. (emphasis added)

76. Additional original jurisdiction

The Parliament may make laws conferring original jurisdiction on the High Court in any matter:

- arising under this Constitution, or involving its interpretation;

- arising under any laws made by the Parliament;

- of Admiralty and maritime jurisdiction;

- relating to the same subject-matter claimed under the laws of different States.”

In Australia, the trend of judicial opinion is to affirm jurisdiction under relevant clauses of ss 75 and 76 exercised against States without their consent: see eg South Australia v Victoria (1911) 12 CLR 667;[30] The Commonwealth v New South Wales (1923) 32 CLR 200;[31] New South Wales v Bardolph (1934) 52 CLR 455, 459; The Commonwealth v Mewett (1997) 191 CLR 471 (Gummow and Kirby JJ, Brennan CJ agreeing); British American Tobacco Australia Ltd v WA (2003) 217 CLR 30.

Chisholm v Georgia was not mentioned explicitly in the judgments in those cases. But they were mostly cases where a State was sued by the Commonwealth or another State, or arising under s 76(i). So those cases did not require a decision under the limb of s 75(iv) that refers to matters between a State and a resident of another State. In Bardolph, which did arise under that limb of s 75(iv), it appears that sovereign immunity was not in contention and the Court just needed to be satisfied about its own jurisdiction.

Section 78 of the Constitution also should be noted. It provides:

“The Parliament may make laws conferring rights to proceed against the Commonwealth or a State in respect of matters within the limits of the judicial power.”

That power has since been exercised.[32] During the Melbourne Convention in 1898, Sir Isaac Isaacs argued that the mere conferral of jurisdiction in the Constitution was enough to curtail sovereign immunity.[33] This view did not, admittedly, command universal assent, and Mr O’Connor moved an amendment which led to the insertion of what is now s 78. But it is difficult to assert that the insertion of s 78 was indicative of unanimity amongst the delegates that legislation was needed to curtail sovereign immunity. Indeed, the prevailing view in the High Court is now that s 78 was not necessary in cases falling within s 75 (as opposed to ss 76 and 77): The Commonwealth v New South Wales (1923) 32 CLR 200, 207, 214-5; British American Tobacco Australia Ltd v WA (2003) 217 CLR 30 [15]-[16], [18] (per Gleeson CJ), [59]-[60] (per McHugh, Gummow & Hayne JJ; see also The Commonwealth v Mewett (1997) 191 CLR 471, 551 (per Gummow and Kirby JJ, with whom Brennan CJ agreed at 491, but see Dawson J at 496-7).

The United States Supreme Court has since rejected the reasoning in Chisholm, by a 5:4 majority, subject to a vigorous dissent.

Importantly, for present purposes, Isaacs J was a member of the High Court in The Commonwealth v New South Wales, decided in 1923. There, the question was whether Commonwealth could bring action against the State of New South Wales in tort in the High Court under s 75(iii), without the consent of the State. Knox CJ, Isaacs, Higgins, Rich and Starke JJ held that the Commonwealth could. Chisholm was cited to the Court in the course of argument.[34]

In joint reasons, Isaacs, Rich and Starke JJ said at pp 208-209 of 32 CLR 200:

“It may be convenient to refer first to the assertion (which is at the root of the defendant’s contention) that an Australian State is a ‘sovereign State’. Learned counsel placed the matter on the same plane as a foreign independent State, the ‘representative’ of which is included in sub-sec. II. of sec. 75. As to such a representative it was said the consent of the foreign State was necessary, and so of an Australian State. There are two fallacies involved in this. The first is that there is any analogy whatever between the position of the ‘representative’ of a foreign State and that of one of the States of Australia … what possible analogy is there between such a case – where person and property are judicially deemed to be outside the territory and beyond the territorial jurisdiction of the local Courts – and the case of an Australian State, an integral and necessary part of the territory of the Commonwealth in relation to this Court? New South Wales is not a foreign country. The people of New South Wales are not, as are, for instance, the people of France, a distinct and separate people from the people of Australia. The Commonwealth includes the people of New South Wales as they are united with their fellow Australians as one people for the higher purposes of common citizenship, as created by the Constitution. When the Commonwealth is present in Court as a party, the people of New South Wales cannot be absent. It is only where the limits of the wider citizenship end that the separateness of the people of a State as a political organism can exist…

The second fallacy in the defendant’s argument is in the use of the expression ‘sovereign State’ in relation to a State of Australia. Before the great struggle of the American Union for existence, costing uncounted lives and treasure, that expression was not uncommon in the United States. And that, despite the warning given by Story J. in his work on the Constitution. He says:- ‘In the first place, antecedent to the Declaration of Independence none of the Colonies were, or pretended to be, sovereign States, in the sense in which the term sovereign is sometimes applied to States. The term sovereign or sovereignty is used in different senses, which often leads to a confusion of ideas, and sometimes to very mischievous and unfounded conclusions.’ (par. 207). The conclusion to which we were invited to come in interpreting the Constitution upon the assumption that New South Wales is a ‘sovereign State’ would be both mischievous and unfounded. The term ‘sovereign State’ as applied to constituent States is not strictly correct even in America since the severance from Great Britain (see Story, par. 208). Still further from the truth is it in Australia…”

Story at those paragraphs refers to the Chisholm case in footnotes.[35]

Isaacs, Rich and Starke JJ went on (at pp210-1 and 213) to rely on the plain and literal reading of s 75.

Their Honours further referred at p214 to the principle of “equal and undiscriminating responsibility to obey the law or make reparation”, and noted at p215:

“As to all cases of controversies in which there might be the element of conflicting interests politically considered, an opportunity was definitely created of invoking the jurisdiction of a tribunal independent of any State …”.

By such reasoning, their Honours followed a similar path to Chisholm.

Their Honours cited Farnell v Bowman (1887) 12 App Cas 643. There, the Privy Council held that the New South Wales Claims against the Colonial Government Act of 1876 (39 Vict. No 38) curtailed sovereign immunity from suit, according to its plain meaning.[36] Farnell has since been described as “epochal” and “cataclysmic”.[37] But it was not the first case to conclude that sovereign immunity from suit had been curtailed. Chisholm v Georgia had decided as much nearly a century earlier.

Conclusion

John Jay’s contribution as a Statesman to the establishment of the United States was monumental. His contribution, particularly as a jurist, has not received the attention it deserves in Australia, which is perhaps not surprising because his time on the Bench was interrupted by other governmental duties. But in his judicial duties his work has had a significant impact including in Australia. His views on the separation of powers have been cited by Dixon J, and relied on in the oft cited case of Marbury v Madison. Indeed, the Hayburn and Chandler litigation set the scene for Marbury v Madison concerning judicial review of executive and legislative action. Further, in the writer’s view, Chisholm, including Jay CJ’s reasoning, shone a light on the path which would later be followed by the High Court of Australia.

[1] The factual background herein draws heavily on George Pellow, Making of Modern Law (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co 1898).

[2] Whom Jay would later run against, and defeat, in the race for Governor of New York in 1798: Mark Dillon, The First Chief Justice: John Jay and the Struggle of a New Nation, pp39-240 (SUNY 2022).

[3] For further reading on his pupillage and his substantial trial experience, see eg Dillon, supra n 2, pp6-18.

[4] An account of his work as Chief Justice is given at Dillon, supra n 2, pp34-5.

[5] Dillon, supra n 2 at p43.

[6] Dillon, supra n 2 pp47, 48.

[7] Making of Modern Law, supra, pp229-230.

[8] Circuit Courts at that time had original as well as appellate jurisdiction (from District Courts).

[9] Dillon, supra n 2, pp52-3, 58-5; Making of Modern Law, supra, p283.

[10] Dillon, supra n 2, p241.

[11] Dillon, supra n 2, p243.

[12] For further reading on his judicial activity, see Dillon, supra n 2, pp34-5, 52-3, 61-5, 71-195, 215-224.

[13] 1 Statutes at Large p243.

[14] The note to Hayburn’s Case, 2 US 408, 410 (1792) must be mistaken when it says the opinion was on 5 April 1791, as that would have been before the Act was enacted.

[15] Note to Hayburn’s Case, 2 US 408, 410-411 (1792).

[16] Ibid.

[17] 1 Statutes at Large, p324.

[18] The case is unreported. For further reading, see Dillon, supra n 2, pp91-111 esp at pp109, 111.

[19] Dillon, supra n 2, pp109, 111. But contra, David Miller, “Some Early Cases in the Supreme Court of the United States”, 8:2 Virginia Law Review pp108-120 (1921).

[20] United States v Todd, 13 How, 52, note.

[21] The Court held that William Marbury was entitled in principle to a writ of mandamus against the Secretary of State compelling the latter to deliver up a commission, but that the Supreme Court could not issue that writ in its original jurisdiction as the Constitution only conferred appellate jurisdiction on the Supreme Court in the present kind of case. The Act of Congress which purported to confer such original jurisdiction on the Supreme Court was to that extent unconstitutional and invalid.

[22] Chandler’s case was cited in argument at p149.

[23] Chisholm had previously sued, unsuccessfully, in the Southern Circuit Court, in Georgia. The Court was comprised of Iredell J and Pendleton District Court Judge.

[24] A member of the Constitutional Convention which framed the Constitution.

[25] Georgia later changed its mind and paid the judgment in 1847: see Dillon, supra n 2, p130.

[26] See Alden v Maine, 527 US 706 (1999).

[27] James Kent, Commentaries on American Law, vol. 1, Lecture XIV, p278 (1826).

[28] Convention Debates (Melbourne 1898) p1675.

[29] Quick and Garran, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth, §324, p 774 (1901, reprinted by Legal Books 1976).

[30] The Court comprised Griffth CJ, Barton, O’Connor, Isaacs and Higgins.