The following is the eulogy delivered by the Honourable Duncan McMeekin KC on 14 February at the funeral of the Honourable Alan Demack AO – former judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland, and a judge of the Family Court of Australia – who died on Tuesday 28 January 2025 aged 90 years.

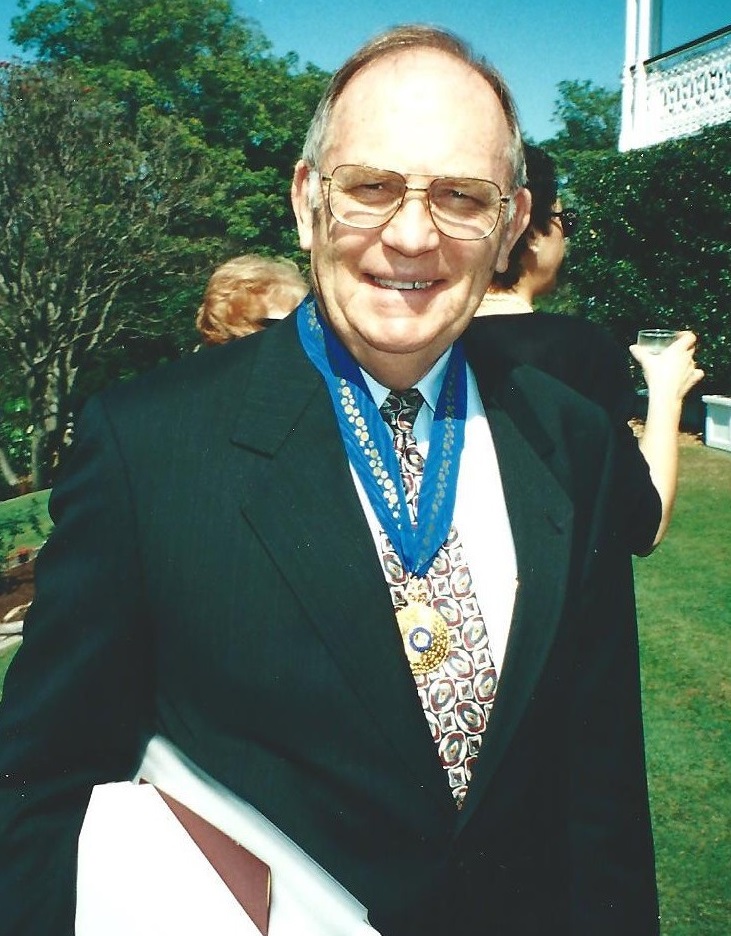

We have gathered here today to honour a legal titan. Most of the congregation know well of Alan Demack’s achievements – his 28 years as a judge and 22 years as Central Judge resident here in Rockhampton, his appointment as an Officer of the Order of Australia and his honorary doctorate in law by the Central Queensland University – but I hope you agree that this occasion requires my brief review of his legal life. When asked to give this eulogy, Anne Demack said to me that on so many dozens of times before Demack J it was McMeekin for the plaintiff and Britton for the defendant and today, in a sense, is my last brief appearing for the plaintiff.

The only advice Alan Demack gave to me when I became a judge was to develop this facility, namely, to be able to look barristers squarely in the eyes and not accept a single word they said. I assumed he was talking to Britton.

So, to a degree, this will reflect my personal recollections, and hopefully I will be partial to Alan George Demack AO.

Alan was called to the Bar in 1957. He had attended Kings College at the University of Queensland from 1953, winning the College’s John Doe prize for Law in 1955 and 1957. He was associate to Sir Roslyn Philp the then Senior Puisne Judge, the second ranking judicial figure in the State, and a renowned jurist, in the year before his admission. Unsurprisingly Alan had written that Sir Roslyn Philp had a significant effect on him.

… there were 13 students in Alan’s class at the Law School in 1953.

To give you some idea of those times there were 13 students in Alan’s class at the Law School in 1953. When I started at the UQ in 1972 there were hundreds. When Stan Jones, who is known to all the lawyers present, became an articled clerk in 1963-4 in his early twenties in a busy litigious firm Stan knew every barrister in Brisbane. Maybe that’s not so surprising, but he told me that every barrister knew him, a mere articled clerk, and by name. It was a very small profession and no doubt Alan’s talents were recognised early in his career. His interests and practice included criminal law, taxation and land law. While his time at the Bar was short he was busy. He found time to serve as Secretary of the Bar Association, as reporter for the Queensland State Reports, and edited the Queensland Justice of the Peace Reports. And he produced two texts as editor – in 1968 the 2nd edition of the Lehane’s District Court Practise and in 1971 he edited the third edition of Allen’s Police Offences of Queensland.

The young Alan Demack was often junior to Sir Arnold Bennett QC and often before the High Court. No QC with any sense entrusts junior counsel to do too much in the case. As Peter Connolly QC said there were two types of junior counsel – those who asked after the case how the case went and those who didn’t. But on one occasion the trial judge interrupted Sir Arnold to say that while the facts were clear to him there was a difficult legal point, and his submissions would be helpful. To which Sir Arnold replied, to Demack’s considerable surprise, “I quite agree your Honour. My learned junior will give your Honour the benefit of our submissions upon the law.” Even so, Demack was entrusted with heavy cases, and on one occasion, alone and without a leader, as Rumpole would have it, appeared before the High Court on behalf of the Federal Commissioner of Taxation.

As I said his time at the Bar was relatively short – 14 years – when he was elevated to the District Courts of Queensland in 1972 at age 37. On the occasion of his swearing in Alan quipped that he had been counselled that: “…the three essentials of a good trial judge are that he be quick, courteous and wrong. I promise to be reasonably quick; I undertake to be unfailingly courteous; and I trust that 66 2/3rds per cent is the pass mark.” I think you all will agree he achieved and superseded the standard he set for himself 53 years ago.

Alan Demack’s long association with his Church and his involvement in lay preaching from his age of 22 made it evident to those around him that he had reflected deeply on life and the problems that confronted people in our society. This combined with his apparent ability to write clearly, and his obvious erudition, resulted in being entrusted in 1973 with chairing the Commission of Inquiry into the Status of Women in Queensland and in 1974-75 he chaired the Commission of Inquiry into the Nature and Extent of the Problems Confronting Youth in Queensland.

As well his time on the District Court was noteworthy at least for his appointment in 1975 for him the first female he appointed as his associate – or as they were then called the clerk – not so often then. The clerk was Margaret Hoare as she then was, demonstrating that Alan Demack was ahead of his times in encouraging a young woman into the profession and prescient in his choice as a future President of the Court of Appeal. Thirty years later, in 2005, Margaret by now Justice McMurdo, was to write of Alan that he was “the model of judicial conduct and courtesy” and that she was then “grateful for his quiet encouragement and wise advice”.

Given the reports following the inquiries he had chaired, and that Alan had produced, it was evident that his talents would be wasted in the District Court and that no-one could be better suited to the new Court that was to be established under the Family Law Act passed in 1975 and Alan was appointed the first Senior Judge of the Family Court in Queensland. He was entrusted by the Attorney of the day to set up and maintain that important Court with newly minted laws yet to be worked out and with newly appointed judges. There was then an enormous responsibility.

I first set eyes on the then Justice Demack in 1976. I was aged 21 and a student at the University of Queensland. I was in the first class to study the new Family Law Act of 1975 and our lecturer invited the newly appointed Senior Judge Alan Demack to address our class. My recollection is of an impeccably dressed man of solemn manner, with a rich voice but quietly spoken. He spoke that day, from my memory of nearly 50 years ago, of his wish that the Family Court that he and his colleagues were to bring into being to be one of informality and expedition. The wigs and robes were to be abandoned, the judges were to sit not at a bench high above the parties but at the same level as the litigants, and the affidavits were to be less full of legalese. He has never spoken of his impressions of we the students, dressed in jeans, T-shirts and shoeless save rubber thongs, but I suspect he hoped we didn’t take informality to these lengths.

In February 1977 I had my first judicial experience with Justice Demack as I instructed John Muir, later to be a great appellate judge, on a custody case. And later that year, and not long admitted, I appeared as counsel before Justice Demack in the Family Court in Rockhampton. I met him then and was invited in for a cup of tea. At that stage there was no court room in Rockhampton and our cases were heard in the Marriage Guidance Council home in Fitzroy St. It was a custody case and I weas opposed by Stan Jones, as he then was. It was certainly informal with the judge seated at a desk a few feet away from the barristers, the witness on a chair a few feet to one side, the entire room the size of a smallish loungeroom. Alan Demack’s manner then was always quiet and courteous, his rulings definite and readily reached.

In January 1978 the still young Demack, aged only 43, accepted an appointment to the Supreme Court of Queensland and to the important position, to each of us in any case, of Central Judge. I was present on the first day he presided in that capacity on 2nd February 1978 and the profession gathered to welcome. I was the most junior lawyer present. Our new judge spoke of the relationship between the Bench and the legal profession:

“Unless there is a strong bond of mutual respect and realistic understanding between the Bench and the legal profession, the burdens on each become intolerable and the administration of justice becomes severely hampered.”

He intended to do his part in fostering that bond and he did.

He commenced the practice of weekly lunches with barristers and monthly lunches with the solicitors’ branch. He organized dinners, at times annually, to celebrate some important event or other. He never missed the annual CQLA conference which for many years was at Keppel Island, and he often being the principal entertainment at the legal dinner whether by speech or song. Their practise was to quit the head table at the conclusion of the meal and go around the tables, usually Dorothy in one direction and he in the other and chat to the practitioners, particularly the younger ones and the out of towners, whom he ensured were made welcome.

There were the traditional cups of tea with the practitioners should there be a settlement of the trial. And each year as the law year ended the Demacks invited the barristers, the members of the judiciary and the Registrar and partners to enjoy a convivial lunch.

During the 1980s the workload in Rockhampton grew dramatically and the lists of cases awaiting hearing numbered in excess of 100. Despite that workload, in 1983 he chaired the Special Committee appointed by the Queensland Government to inquire into the laws relating to artificial insemination, in vitro fertilisation, and other related matters. Yet his application to his work never flagged. His lists were well managed and his judgments timely.

Of course, the Central Judge had extensive responsibilities to the wider area including Mackay, Bundaberg, Maryborough, and Longreach. Mackay, in particular, was a busy litigious hub. In a tribute in 2011 a former associate Alison Buchhorn, who some here will recall as Alison Nightingale, recalled of Mackay: “You could be sure of a full calendar for each two week visit and if any trials required adjournments causing the list to collapse, there was one solicitor in particular who was notorious for arranging civil trials at short notice so that every hour of the day was used wisely.” Alison didn’t name the solicitor she had in mind but his initials I am sure are Gene Cristopher Paterson. And to be fair the solicitor on the other side had to co-operate and very often that opponent was John Taylor. The pair of them sit together here today, along with others who have travelled from Mackay to honour and respect the judge on whom they had for so long relied.

It would be remiss not to mention Alan Demack’s sense of humour that was always lurking. On one occasion he was asked to attend a view of the site of a car accident. We duly went to this relatively remote rural setting somewhere west of Raglan in three relatively up market motor vehicles. There were attending the two barristers, their two instructing solicitors, the judge and the court reporter – six of us all dressed in business suits. Demack drily looked at us all and remarked that our attendance, when noted by the locals, would cause rural land values to enjoy an exponential improvement as the locals wondered what was up.

“if you want to try a plea bargain, I’ll drop the flogging.”

On another view of a scene, this time of the site of a burglary, it became evident that my client, the miscreant, had made up a story of an accidental entry in the night, an account that could not be remotely true as it required improbability on improbability. Somewhat crestfallen as we re-entered the car back to the courthouse the judge said to me – “if you want to try a plea bargain, I’ll drop flogging”.

On one occasion at Keppel Island for the annual conference he somehow ended up taking our daughters, then in their early teens, out for a sail off the beach in a catamaran. I do not think he claimed to be a great sailor and the boat did appear to be heading rapidly towards the mainland at one point which seemed to be in the wrong direction – so much so that the girls later reported that they had panicked more than somewhat and used profane language, language that they had picked up no doubt from other sailors, and usage the judge seemed not to be familiar with, which language I gathered was along the lines of “Holy, Jesus Christ”. But when Demack returned he was full of smiles and commented that the children were beautifully behaved and even given to prayer.

Every barrister who practised regularly in in Rockhampton or Mackay and found themselves elevated to the bench of a Court would remark, when appointed, that they hoped to emulate Alan Demack’s demeanour and behaviour. I know I did try. But one day one of our former colleagues, who had expressed such sentiments to Alan himself upon his elevation, managed to be later barred from a golf club for among other things shouting expletive laden remarks in the general vicinity of the female members while digging up the green with his putter. Alan, on hearing of this episode, remarked to me in passing that he was unsure of precisely what aspect of his demeanour or behaviour the judge was emulating.

It is worth remarking that from the relatively few barristers who were members of the Bar resident here or in Mackay or who were Central Crown Prosecutors, who numbered only five in 1977 when I joined the Bar, and who numbered never more than about 10, the list who were in time elevated to a Court are a testament to the high standards he had encouraged. They include Keith Dodds, Bob Hall, Peter White, Trevor Morgan, Kerry O’Brien, Marshall Irwin, Brian Harrison, Stan Jones, Grant Britton, and our present Central Judge, Justice Graeme Crow. Their affection and regard was well known among us, and to him. I have left Judge Anne Demack out of the list assuming her elevation due to more a reflection of familial influence, although her many years as Alan’s associate no doubt allowed her to study his technique at close hand. Her invariable reference to her father as “Pop J” when communicating to the barristers kept the light-hearted communications open.

Demack had a fine baritone voice that he has used to good effect on many an occasion — controlling a court room, leading the congregation in a hymn and on occasion entertaining the lawyers at a social gathering. The legal profession in Central Queensland has a strong Irish Catholic influence and they too enjoy their singing. Whilst he professes to know no Irish songs, a proposition that some lawyers have expressed difficulty in accepting, [the account is in fact that at a legal dinner and after a fine song from Demack J John Taylor from Mackay who had flown down to the dinner with colleagues and who had become very tired and emotional by this time of the dinner asked Justice Demack to sing an Irish song. Demack replied that he did not know any Irish songs. Taylor: “Sing us a fucking Irish song”. Demack: “I don’t know any of those either”] Alan Demack has written songs that remain favourites amongst a generation of lawyers throughout Central Queensland. His ode to ‘Tim the Termite’, first sung at a legal dinner struck a resonant chord with the profession. It was at a time when the old Supreme Court building, in use since 1888, had become sadly dilapidated and although to be pressed into use for another decade, was nearing the end of its time as a Courthouse, held together, it was said, by strings of termites. His sense of humour is manifest in the closing verse of that song:

“When the air conditioning’s on the blink, you have to fight for breath,If it ever rains on the roof again the noise could make you deaf,But justice is the outcome if the case is fairly fought,So we’ve termites holding hands to keep up Rocky’s Supreme Court.

On 19 May 2000 the tenth and longest serving Central Judge retired. Several dinners were held, one of which was at Elizabeth and my home at Gracemere in our garden under the stars with the Chief Justice, the President of the Court of Appeal, our newly elevated Central Judge Peter Dutney, and many of the senior solicitors and barristers from Mackay, Gladstone and of course Rockhampton were present.

A more formal dinner was held in his honour at the Rockhampton Club. As a sign of the affection and respect in which he and his wife Dorothy were held the profession gathered in numbers. As a parting gift the profession gave the Demacks the complete set of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, the composer that he admired above all others. And for the last time “Tim the Termite” was sung – this time by the assembled profession to him.

Alan Demack told his son, Jim, that on his retirement he was to spend more time pursuing his interest in legal history, theology and music. As for the latter I heard from John Weary, Alan Demack’s long time bailiff and organist in this Church, who plays for us today, that there had been some pretty vigorous in-fighting on the suitable hymns to be on the roster each Sunday. And in a letter to apologise for missing our Judge’s cocktails in 2013 he wrote that he and Dorothy “will be sitting in the State Theatre Melbourne listening to the third opera in Wagner’s Ring Cycle, Siegfried.”

He may have retired but his legal work was not finished. Shortly after his retirement Demack became the inaugural holder of the Office of Integrity Commissioner, he produced a handbook for guidance on Public Officials, and at age 72 he was the Chair of a three-person committee appointed to oversee the redistribution review of Queensland’s 89 electoral boundaries.

Our last legal gathering for him was on the occasion of his 80th birthday when a dinner was held in the old courtroom where he had for so long presided. Every barrister and judicial officer resident here in Rockhampton and their partners were present. Justices Margaret and Philip McMurdo honoured him by their presence and Margaret offered a lovely tribute. My contribution was a toast by the profession to him and Dorothy in the form of a roast. It was along the lines that he had no loyalty at all as he had abandoned every court he had been a member of, quitting the District Court, quitting the Family Court, and abandoning the Supreme Court after only 22 years of service with plenty of years still left; his work as integrity commissioner hadn’t had much effect on our politicians; and his allegedly famous judicial courtesy had cracked not once nor twice but three times over 28 years, admittedly to the same practitioner twice. I received a letter from Alan a few days later thanking me for the speech. I still have the letter and I quote:

“It is surprising how the years drag us forward when there still seem to be so many things left undone ages ago. Still it is a delight to look back to see what has been done. It is even more pleasant to hear people talk about times past with evident respect and affection.”

Your presence here today reflects the respect and affection so many have for him.

“Justice Demack has exemplified in large measure all of the qualities considered as typifying the very best judges …”

At his valedictory the then Chief Justice Paul de Jersey said of Alan Demack and said, with respect, very accurately:

“Justice Demack has exemplified in large measure all of the qualities considered as typifying the very best judges: an irrevocable personal commitment fearlessly and independently to uphold the rule of law, unquestioned moral character and probity, high intellect and well informed legal learning, compassionate sensitivity to cultural gender and ethnic considerations, a lively interest in legal history and the roots of the common law, in court – calm rationality expressed with patient courtesy, and out of court – a capacity to interact beneficially with the local community, facilitating a better understanding of the judicial process, and while attracting the admiration of that community, effectively preserving the necessary authority of the Court and of his judicial office.

A great summary of a great and well lived life.

But I will leave the last word to Alan Demack. His philosophy he summarised for the graduating class of 1985 at the then Central Queensland Institute of Advanced Education:

“May you always pursue excellence guided by a thirst for knowledge, an unreasonable cheerfulness, a commitment to an ideal, and a willingness to share.”

To so many of us, for decades of our lives, he was our judge, May he rest in peace.

Grant Britton KC passed away on 19 November 2024, aged 78 years, after a short and unexpected illness.

Few of the Bar would know much about him. He was a quiet man and spent much of his life far from Brisbane. He spent most of his career based in Rockhampton – a barrister practising there for nearly 20 years and then the resident District Court judge for 14 years. But he was an accidental lawyer. I do not mean one prone to mistakes – quite the contrary – but one who, when young, never envisaged the life he came to lead.

He graduated from Banyo High School on the north side of Brisbane, and in response to an advertisement for an articled clerk he applied. He had no idea what an articled clerk was, or whether it was any different from a clerk employed anywhere else, indeed he expected a position with something like a junior at Woolworths. Hence, he started with no knowledge or expectation of being a lawyer, but he ended up with Don McDonald, solicitor of Brisbane, and entered into articles for ultimate admission as a solicitor.

Grant felt proud of the fact that he was, he believed, the first graduate from his high school to ever become a lawyer, a mistaken career as it was. Many decades later he was invited to a celebration of the 50th anniversary of his alma mater. Rightfully so, as he was the first lawyer from their ranks. Unfortunately, at the gala dinner, it became apparent that the organisers had intended to invite a prominent footballer of the same name and not Judge Britton SC. Such is fame.

After his servitude with Don McDonald – a colourful tutor who was struck off the roll eventually – and admission as a solicitor in 1969, Grant took up partnership with Gilshenan and Luton, then and now a legal firm noted for its expertise in the criminal law. Bill Weir recalled they were admitted to partnership together in 1973, with Grant in charge of civil litigation and more the cerebral lawyer, better suited, Bill thought, to a barrister’s practice. The barristers retained by the firm and who Grant watched in action included the best of their time and who would grace a court perhaps at any time: Peter Connolly, Bill Pincus, Des Sturgess, and Bill Cuthbert. Some training for the barrister he would become!

Times were very different then. Grant once told of briefing Bill Pincus – later a Federal Court judge and one of the inaugural judges of the Queensland Court of Appeal – who then was a relatively young practitioner. Grant was then about 19 or 20 years old. A doctor was to give evidence in Grant’s client’s case and arrived at counsel’s chambers for a pre-trial conference, albeit dressed in his “tropical” outfit of shorts, long socks, short sleeve shirt. Pincus could not believe his eyes. In Grant’s presence, Bill rang the presiding judge – the stern Chief Justice Mansfield – and said words to the effect (deleting expletives) that this fool of a medical witness has come so dressed and inquired whether the Chief Justice would hear him? A strong “no” was the response from the Chief, and the doctor – suitably chastised by Pincus – was sent hurriedly off to the local haberdashery.

Good luck today getting a medical practitioner to a courtroom let alone to your chambers, and the last doctor I saw had been apparently guided in their attire by an episode of “Scrubs”! And judges today would not so much as blink at – indeed would gratefully welcome – a neatly attired witness.

Another anecdote from those days but of more noble content: A solicitor – who Grant barely knew – handling the other side of a personal injury case rang him at home one Sunday. The practitioner said that he had been going through his files and said merely that Grant might look closely at his own file. He did. Grant, to his horror, saw that he had not issued the Writ, as we then did to commence proceedings and stop time running under the statute. The limitation period expired the next day, so Grant’s virtually unknown colleague saved him from the certainty of a professional negligence suit. The profession was smaller then and Grant’s gratitude to the kindness was fondly remembered decades later.

In February 1977, nine years after admission as a solicitor, Grant was admitted to the Bar. By then he had an honours degree in law. He joined More Chambers, then in Ansett House in Turbot Street (now the Hotel Indigo). He enjoyed a convivial group there with the work an emphasis more on the criminal side. His chamber mates included Don Muller, Mac Boulton, Des Breen, and Kerry and John Copley, and they remained on good terms in the years ahead.

The Central Queensland chapter of Grant’s career started in 1979. While he enjoyed what was a good start to practice in the city, he had a growing family, an alarming number of newly admitted barristers competing for briefs, and an opening – he was told – in Rockhampton. His great friend Bruce Forbes, a solicitor in Gladstone, told him of untold numbers of briefs available and too few barristers. He moved, and the rest is history.

Grant took over the chambers of Dan Ryan, who headed off to the solicitor ranks, and so joined me in chambers upstairs to a bank, in three rooms that cost us the princely rent of $26 per month, each including parking, an amount Grant never remembered to pay. The landlord, the manager of the CBC Bank, was hardly concerned; he apologised for charging any rent, given the contest between the cockroaches and the rats in the rooms.

In 1977 when I joined the Bar in Rockhampton there were three others – Bob Hall, Stan Jones and Dan Ryan. In 1979 Keith Dodds and Peter White joined us at the private bar but practising from three different chambers. In 1982 Grant and I joined Stan Jones and Bob Hall, and together purchased 170 Quay St, chambers that barristers had used since the 1930s. Hence, six of us, from that point, shared a “home”. Each of us was destined to become a judge: Hall (in 1983), Keith Dodds (in 1986), White (in 1992), Jones SC (in 1997), Britton SC (in 1998), and me (in 2007). Indeed, it is worth noting that Keith Dodds, as Central Crown Prosecutor, was replaced by Marshall Irwin, later Chief Magistrate and District Court judge, and then by Kerry O’Brien, later Chief Judge of the District Court.

Circa 1989 – Grant Britton, Anthony Mellick. Demack J, Dodds DCJ, Jones QC, Brian Harrison, Duncan McMeekin

In consequence – from 1979 in particular – we were opposed every day by practitioners of uniformly considerable experience and talent. While making our professional lives more demanding, it served to improve our professional skills immeasurably.

Grant enjoyed immediate success with much of his work coming from Gladstone and Emerald practitioners. Indeed, Dan Ryan had left some 50 briefs on his floor from John Crossan, solicitor of Emerald, as a welcome gift. And he enjoyed career long support from the prominent Rockhampton solicitors, especially John Shaw of Swanwick Murray Roche and Tom Carmichael of South & Geldard. Grant’s success in his early years before the local Magistrates was truly remarkable. I would jibe him that he plainly thought like a Magistrate as often their reasoning – which he clearly followed – was often obscure to many of us. However he managed to do so, and he rarely lost. As a result, he developed a strong following among the solicitors. This stood him well as the more complex cases came along.

But there was not unalloyed success. One day he strolled into chambers looking relaxed. “What’s on” I asked. “A walk in the park” he responded. “Before the Planning Court with a litigant in person. Back in half an hour”. He was right about that much. He came back looking pretty dejected. “Yes, a litigant in person,” he said, “But he beat me on a point of law”.

Grant enjoyed a varied practice but as the years passed, he concentrated on the civil side and usually in the Supreme Court. His work was marked by a thorough and careful approach. He was not given to overstating his case. His manner was invariably calm and his approach to witnesses courteous. He was of the school who believed that honey would be more successful than vinegar. We were both opposed and often before the great Justice Demack.

So often were we opposed that I could with some confidence anticipate his expected cross-examination on any given topic. And no doubt he thought of mine. On a celebration on his appointment as a District Court judge – in my toast to him – I commented that in our near 20 years in chambers together and opposed in court we had not had a serious argument. A poor choice of words; Justice Demack – with his quiet humour – observed, as to the latter, that he could confirm that indeed we had not.

Grant Britton and Dorothy Demack

Generally, when discussing the goings on among the chamber mates, a mention is made of their collective effort to secure their futures by identifying profitable investments. In this we were spectacularly unsuccessful. Pride precludes me identifying the worst but some are prime candidates.

The suburban Rockhampton home purchase which we made and then rented seemed innocuous at the time, but our subsequent identification in the 1988 Fitzgerald Commission on Corruption as owners of the leading brothel in Rockhampton conducted by our tenant – who never missed his rent, and over the road from the Anglican’s Bishop’s home – was disconcerting. Especially so for Grant as he enjoyed the role as Chancellor of the local Anglican Diocese.

A close run in the disastrous investment stakes was the block of flats that we – being Stan Jones, Grant and me – failed, much to our chagrin, to even so much as visit before purchasing them. The units turned out to be over the way from the city rubbish tip, the “way” being the rail tracks over which came frequently the one kilometre long coal trains, and next to the busiest pub in the city. Worse still, we could not agree among us who should have the task of evicting the tenants who had used the lounge carpet as the ideal place to carry out repairs on their motorbikes. Their membership of the “Rebels” did cause us pause to volunteer.

Perhaps these investment debacles founded some impetus for each of us to secure a judicial pension as a means of surviving in our retirement.

Grant was granted silk in November 1998 and a week later was appointed a judge of District Court in Rockhampton, upon Judge Nase moving to Beenleigh. While he held commissions as a judge of the Planning and Environment Court and the Children’s Court, Grant’s 14 years on the bench consisted principally of the conduct of criminal trials and sentences. While his background at the Bar was on the civil side, he took well to the criminal work.

Unfortunately, with age, Grant was afflicted with significant hearing loss. He insisted on having the trial transcript, including submissions, before him in preparing his summing up. This, perhaps, ensured that he was rarely overturned on appeal. Counsel knew him to be careful and invariably courteous. There are two types of judges – those who ask and intervene and those who don’t. Grant rarely spoke and had a reputation of some asperity. This was far from true. I often met him as he quit the court chuckling at the goings on during a trial.

Grant had the usual course of young lawyers as associate, but he eventually settled on his old friend Gordon Roberts as his associate for the last years on the Bench. Gordon had been Registrar of the Supreme Court in Rockhampton for the previous 20 years and by now in his seventies. Gordon’s penchant to drift off in the afternoon proceedings, combined with his and the judge’s profound deafness, resulted in some hilarity in the courtroom as the judge would endeavour to attract the associate back to the business of the court. “What did he say?” he asked to Gordon of the counsel’s question. “What did you say Judge?” “No, what did he say.” “No, I didn’t hear what you said Judge.” “No, what did counsel say”. Eventually the bemused counsel would shout out their last question.

I have glossed over his family life. He and Denise, his first wife, enjoyed an active social life, often entertaining at their home, which we often enjoyed. They had five children together, a son Tony and four daughters, Geraldine, Angela, Rebecca and Melissa. One, who perhaps should not be identified, but who was not a daughter, at the age of three, managed to burn their home down after finding a box of matches. But none were hurt. He greatly loved them and thoroughly enjoyed a large family. Their marriage faltered and they eventually parted. Grant and Christine then married, thereby gaining two more children, Mike and Kate, of Christine’s first marriage, and they spent some 25 years together.

Grant’s first love was carpentry and, through his life, enjoyed and was skilled at his woodworking hobbies. He retired to a small farm in Maleny to enjoy his hobbies, and where it was joked – so steep was his block – his cows often fell to the creek far below. He and Chris only recently moved to Toowoomba to be closer to family and start a new life. Sadly, he was not to enjoy it.

Circa 1989 – Grant Britton, Anthony Mellick. Demack J, Dodds DCJ, Jones QC, Brian Harrison, Duncan McMeekin

Circa 1989 – Grant Britton, Anthony Mellick. Demack J, Dodds DCJ, Jones QC, Brian Harrison, Duncan McMeekin

Grant Britton and Dorothy Demack

Grant Britton and Dorothy Demack