The Australian Military Court replaces the system of individually convened trials by Court Martial or Defence Force Magistrate. The court will be a ‘service tribunal’ under the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982. It is an important part of the military justice system, which contributes to the maintenance of military discipline within the Australian Defence Force.

Establishing the court is one of many reforms to the military justice system. The enhancements ensure a modern and effective approach to military justice, while striking an appropriate balance between effective discipline to allow Australian Defence Force personnel to operate safely and effectively, and protecting individuals and their rights.

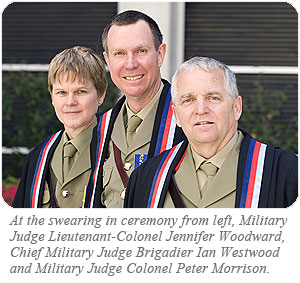

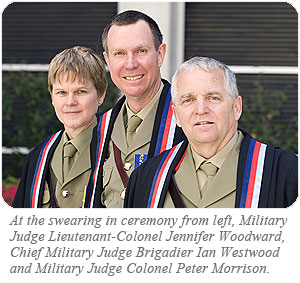

Brigadier Ian Westwood AM was sworn in as the first Chief Military Judge at a ceremony in Canberra on October 3. He has 24 years of military law experience gained through full-time Army service. He was admitted to the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 1978 and appointed to the Australian Army Legal Corps in 1983. Brigadier Westwood, who resides in Canberra, is responsible for ensuring the orderly and expeditious discharge of the business of the Australian Military Court and managing its administrative affairs. He will also sit as a military judge on the court and report to Parliament annually through the Minister for Defence.

Brigadier Ian Westwood AM was sworn in as the first Chief Military Judge at a ceremony in Canberra on October 3. He has 24 years of military law experience gained through full-time Army service. He was admitted to the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 1978 and appointed to the Australian Army Legal Corps in 1983. Brigadier Westwood, who resides in Canberra, is responsible for ensuring the orderly and expeditious discharge of the business of the Australian Military Court and managing its administrative affairs. He will also sit as a military judge on the court and report to Parliament annually through the Minister for Defence.

Two permanent military judges, Colonel Peter Morrison and Lieutenant Colonel Jennifer Woodward were also sworn in. Colonel Morrison, hailing from Townsville, has a combination of private and military legal experience spanning more than 26 years. He was a Judge Advocate and Defence Force Magistrate prior to his appointment.

Lieutenant Colonel Woodward was previously a senior prosecutor for the Australian Capital Territory and a commercial litigation practitioner. Prior to becoming a military judge, she was Director of Advisings, General Counsel Branch, Department of Defence. Lieutenant Colonel Woodward also spent seven years as a permanent legal officer in the Army.

At the swearing in ceremony, Chief of the Defence Force Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston said Defence was strongly demonstrating its commitment to improving the military justice system and delivering impartial and fair outcomes through enhanced oversight, greater transparency and improved impartiality.

“Since the beginning of my tenure as Chief of the Defence Force, I have been absolutely delighted with the progress we have made to our military justice system,” he said.

“It is critical to the Australian Defence Force’s operational effectiveness and the protection of individuals and their rights that we have a strong military justice system — one that not only underpins our discipline and command structures but also enables our personnel to work in a fair and just environment.”

“It is critical to the Australian Defence Force’s operational effectiveness and the protection of individuals and their rights that we have a strong military justice system — one that not only underpins our discipline and command structures but also enables our personnel to work in a fair and just environment.”

The new court is judicially independent from the military chain of command and Executive and, although based in Canberra, is fully deployable and able to conduct trials within Australia and overseas, including operational areas.

The Australian Military Court has the same jurisdiction as Courts Martial and Defence Force Magistrates did previously. It only exercises jurisdiction under the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 where proceedings can reasonably be regarded as substantially serving the purposes of maintaining or enforcing discipline. The Australian Military Court meets the disciplinary needs of the Australian Defence Force in maintaining and enforcing Service discipline by trying more serious or complex Service offences.

How does it work?

As well as the Chief Military Judge and two permanent Military Judges sworn in recently, there will be a panel of part-time (Reserve) military judges. Military Judges are independent from the military chains of command and Executive in the performance of their judicial functions. They may sit alone or with a military jury. Military jurors perform a role akin to jury members in a civilian court system and determine on the evidence whether an accused person is guilty or not guilty of the Service offence.

Essentially, the trial procedures of the Australian Military Court are similar to those of civil courts exercising criminal jurisdiction. The general principles and laws of criminal responsibility as provided for within the Criminal Code (Commonwealth) apply in respect of Service offences prosecuted before the Australian Military Court, as do formal rules of evidence. The presumption of innocence to the accused applies as it does in a civil court which means that the prosecution is obliged to prove the case against an accused beyond reasonable doubt.

Essentially, the trial procedures of the Australian Military Court are similar to those of civil courts exercising criminal jurisdiction. The general principles and laws of criminal responsibility as provided for within the Criminal Code (Commonwealth) apply in respect of Service offences prosecuted before the Australian Military Court, as do formal rules of evidence. The presumption of innocence to the accused applies as it does in a civil court which means that the prosecution is obliged to prove the case against an accused beyond reasonable doubt.

All prosecutions before the court are conducted through the office of the statutorily independent Director of Military Prosecutions, Brigadier Lynette McDade. This area consists of several full-time and Reserve prosecutors. The Directorate of Defence Counsel Services, led by Group Captain Chris Hanna, arranges legal representation for the accused. The directorate administers the Defence Counsel Services Panel, which contains more than 150 lawyers from Army, Navy and Air Force who are located across Australia. These lawyers are admitted to practise in a State or Territory of Australia and come from various branches of the legal profession.

Colonel Geoff Cameron, who is the statutorily independent Registrar of the Australian Military Court, assists the Chief Military Judge with the administration of the court and discharges statutory functions.

Other changes to the military justice system include introducing rights of appeal from decisions of the Australian Military Court to the Defence Force Discipline Appeals Tribunal (presided over by tribunal members who may be Federal Court, State or Territory Justices or Judges). In the case of the accused it is available on both conviction and punishment or court order. In the case of the Director of Military Prosecutions it is available for punishment or order only. Following the next tranche of legislative changes, an accused will also have the right to elect trial by the Australian Military Court for certain categories of disciplinary offences.

If an accused is found guilty, punishment as provided for by the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 is imposed by the presiding military judge taking into account mitigation evidence, the sentencing principles applied by civil courts and the need to maintain discipline in the Australian Defence Force.

Enhancing impartiality and fairness

Enhancing impartiality and fairness

The selection of the Chief Military Judge and Military Judges was through an independent merit process. They were selected from current qualified Permanent and Reserve Australian Defence Force legal officers and any other person who satisfied the statutory selection criteria.

Key features of the Australian Military Court include:

- statutory appointment of legally qualified military judges,

- security of tenure (10 year fixed terms),

- remuneration set by the Commonwealth Remuneration Tribunal,

- mid-point promotion during tenure,

- the necessary para-legal support to be self administering,

- judges to sit alone or with a jury in the case of more serious offences (military judge presiding), and

- appeals on conviction or punishment to the Defence Force Discipline Appeals Tribunal.

The Australian Military Court proceedings are open to the public except where the Military Judge orders otherwise (for example, if it is contrary to the interests of security or defence of Australia, the proper administration of justice or public morals).

Further enhancements to the military justice system

The Australian Military Court is one of a range of enhancements to the military justice system being introduced by Defence. With the two-year implementation schedule due to finish at the end of this year, Defence is well advanced in putting in place the most significant changes its military justice system has seen in more than 20 years. Twenty-three of the 30 agreed recommendations from the 2005 Senate Report ‘The effectiveness of Australia’s Military Justice System’ are now complete.

Major achievements to date include:

- A new joint Australian Defence Force investigative unit now investigates serious incidents with a service connection.

- There is no longer a backlog of complaints and redresses of grievance due to the additional resources being provided and the hard work of Defence personnel.

- A civilian with judicial experience now presides over Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) Commissions of Inquiries into deaths of ADF members in service or other matters as determined by the CDF.

- The Learning Culture Inquiry Report into ADF Schools and Training Establishments was released in December 2006. It followed the military justice inquiry, which found that some aspects of ADF culture may be related to deficiencies in the military justice system. Action to reinforce ADF culture consistent with core values has reduced the risks of inappropriate behaviour, improved the care and welfare of trainees, and improved the management of minors in particular. More than half of the agreed recommendations are now underway.

For further information about the range of enhancements to the Military Justice System visit, www.defence.gov.au/mjs

Cristy Symington

Queensland barristers are now safely ensconced in their chambers following the Christmas period. Many of us enjoyed a holiday. For most it was too short; for some too long.

A lengthy and recuperative holiday from practice, paradoxically, can sometimes be inimical to practice upon resumption. A lengthy break often retards efficient dispatch when back at work; one can still feel the sand between one’s toes.

Counsel, like a number of professions and callings, do work in a pressured environment. The cab rank rule dictates we cannot pick and choose our briefs. Acting for the occasional scoundrel and the desperado founds a mountain of tension (and that is just on the commercial list!).

As barristers are self-employed, taking holidays from work, and taking apt recreational time during the work week and at weekends, is paramount. To do otherwise works deleteriously not only to the barrister’s personal health and fitness (mental and physical) but also to the maintenance of his or her marriage (or other union), family life and social enjoyment.

Counsel, generally, are well remunerated. Partly for that reason, but saliently in expectation of professionalism, instructing solicitors and clients justifiably anticipate we will always perform at 100%. They eschew any gripe apropos how “busy” or “tired” we are. Adequate rest and leave enhance our meeting these proper expectations.

Self-employment obviates delegation (except to the extent that occurs between senior and junior and between barrister and solicitor). In consequence many of us tend to work excessively long hours and plan poorly for recreational and holiday time. The profession needs to redress this.

Self-employment obviates delegation (except to the extent that occurs between senior and junior and between barrister and solicitor). In consequence many of us tend to work excessively long hours and plan poorly for recreational and holiday time. The profession needs to redress this.

Not for one moment am I suggesting we all need be routinely planning travel to some far flung destination. Different folks, different strokes. Staying home with the spouse, the kids and the dog may be as restful, if not more so than an interstate or overseas jaunt.

Informed by these matters, my experience in 25 years at the Bar yields the following golden rules about holidays, and generally time off work.

First, only work six days a week.

Almost all of us work at least five reasonably long days, both at work or at home after the evening meal. With the occasional necessary exception, never work more than six days a week. Saturday is an important day to spend with your partner (and your children if you have them) and/or your friends, or just by yourself (eg, reading, golf).

Secondly, drink alcohol regularly but not copiously.

With respect to the teetotallers at the Bar (and I only know one, and he is more fun than all the others who drink), to have at least one or two (I always lose count) alcoholic drinks at home at night serves to melt work and domestic tension. My wife and I practise marriage by the mantra: “The couple that drinks together stays together”. Excessive consumption is a problem; there has been many an alcoholic barrister.

Thirdly, diarise holidays.

Cross holidays out of your diary just like you cross out time to do a case or undertake some paper work. Be zealous in maintaining such work unavailability irrespective of what happens. Another brief will always come along.

Fourthly, inform solicitors of your holidays.

When speaking periodically to your briefing solicitors, or if there is a significant gap between conversations then by short letter, timeously advise them you will be taking holidays, and thereby unavailable during a particular period. They cannot sensibly, and rarely will complain if fully informed. If they do they are not worth having. Most will see it as proper and admirable allocation of your time.

Fifthly, no briefs on holidays.

Inexorably several briefs remain unfinished before holidays, or a trial soon thereafter behoves preparation. Never take a brief (or any legal journal) with you on holidays. Not only is the study of it unlikely to be productive, but it will retard your relaxation and social productivity.

Sixthly , no work contact on holidays.

Do not take or make business calls on holidays. To do so will only disrupt your relaxation time and irritate your partner or companions. Tell any caller, and bluntly, that you are on holidays and thereby you are not in a position to respond.

Seventhly, immediately plan your next holiday or time off.

If you arrive back in chambers in mid-January, strike out a week at Easter. At the end of Easter strike out a week in September, etc. However long the lead time to, or work intensity until your next holiday, your productivity will thereby be enhanced and frustration diminished if you are mindful that your next holiday has been “locked and loaded”.

Candidly, I have breached each of these rules from time to time. That does not detract from their efficacy. Each ought be borne steadily in mind. Act now! You are a long time dead or divorced.

Candidly, I have breached each of these rules from time to time. That does not detract from their efficacy. Each ought be borne steadily in mind. Act now! You are a long time dead or divorced.

My word or phrase of the week: “Parkinson’s Law – the law that dictates that ‘work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion’. The term was first formulated by the English historian and author Cyril Northcote Parkinson (1909-1993) in his eponymous 1957 text [source: Chambers’ Dictionary of Eponyms – 2004, pg 222].

Richard Douglas SC

Discuss this article on the Hearsay Forum

Immediately below is a list of Judgments included in this issue. The summary notes follow thereafter. To be taken to the full text of the Judgments, click on the case name at the top of each summary note.

- Sons of Gwalia Ltd v Margaretic; ING Investment Management LLC v Margaretic [2007] HCA 1, 31 January 2007

- Klein v Minister for Education [2007] HCA 2, 1 February 2007

- Leach v The Queen [2007] HCA 3, 6 February 2007

- X v Australian Prudential Regulation Authority [2007] HCA 4, 21 February 2007

- Commissioner of Taxation v McNeil [2007] HCA 5, 22 February 2007

- Leichhardt Municipal Council v Montgomery [2007] HCA 6, 27 February 2007

- Z v New South Wales Crime Commission [2007] HCA 7, 28 February 2007

- Forsyth v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2007] HCA 8, 1 March 2007

Sons of Gwalia Ltd v Margaretic; ING Investment Management LLC v Margaretic [2007] HCA 1, 31 January 2007

A person who buys shares in a company in reliance upon misleading or deceptive information from the company, or misled as to the company’s worth by its failure to make disclosures required by law, may have a claim for damages against the company which ranks equally with claims of other creditors, the High Court of Australia held today.

Sons of Gwalia Ltd was a publicly listed gold mining company. On 18 August 2004, Mr Margaretic bought 20,000 shares for $26,200. Eleven days later, administrators were appointed pursuant to the Corporations Act, and the shares were then worthless. Mr Margaretic alleges that Sons of Gwalia failed to notify the Australian Stock Exchange that its gold reserves were insufficient to meet its sale contracts and that it could not continue as a going concern. He says he is a victim of misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of the Trade Practices Act, the Corporations Act and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act. He sought compensation for the lost value of the shares. Many other shareholders have similar claims.

The proceedings have been brought to test the entitlement of shareholders in Mr Margaretic’s position to make a claim, in competition with other creditors, under the deed of arrangement for distributing funds to creditors. The deed administrators applied to the Federal Court of Australia for a declaration that Mr Margaretic’s claim is not provable in the deed of arrangement or alternatively that payment of the claim be postponed until all debts owed to persons other than in their capacity as Sons of Gwalia members are met. ING, a creditor, but not a shareholder, was named as the second respondent. Mr Margaretic cross-claimed for a declaration that he is a creditor entitled to all the rights of a creditor. Justice Arthur Emmett made such a declaration and further declared that his claim is not postponed until all other debts have been satisfied. The Full Court of the Federal Court dismissed appeals by Sons of Gwalia and ING, who then appealed to the High Court.

The Court, by a 6-1 majority, dismissed the appeals. Section 563A of the Corporations Act provides that payment of debts such as dividends owed by a company to someone in their capacity as a member of the company is to be postponed until all debts owed to persons otherwise than as members of the company are satisfied. The Court held that this did not apply to a shareholder claiming damages for the loss sustained in their acquisition of the shares when the shares were less valuable than represented, or would have been revealed to be the case had proper disclosure been made. Mr Margaretic’s claim is not one owed to him in his capacity as a member of the company, therefore section 563A does not apply to it. The claim falls within section 553 of the Act, which provides that only claims arising before the relevant date – in this case, the date Sons of Gwalia went into administration – will be considered a debt against the company.

———

Klein v Minister for Education [2007] HCA 2, 1 February 2007

The High Court of Australia today revoked its grant to former Perth security guard Mr Klein of special leave to appeal.

Mr Klein worked for Falcon Investigations and Security, which had a contract with the Minister to provide security for designated public schools in the State. On the night of 1 November 1999, while patrolling Perth schools, he was called to a primary school where a youth was smashing windows. Chasing the intruder through knee-high grass in the school grounds, Mr Klein fell. His injuries included a broken kneecap. He was unable to continue to work for Falcon.

Mr Klein brought an action against the Minister in the WA District Court under the Occupiers’ Liability Act. The Minister argued he was a deemed employer under section 175(1) of the then Workers’ Compensation and Injury Management Act. He relied on the 2002 decision by the Full Court of the WA Supreme Court, Hewitt v Benale Pty Ltd, that the deeming by section 175(1) of both principal and contractor as employers meant that the constraints on damages in the Act applied to injured workers bringing action, independently of the Act, against a person who was deemed by section 175 to be their employer. Mr Klein argued that, because section 175(3) provided that a principal contractor was not liable unless the work on which the worker was employed was directly a part or process in the principal’s trade or business, the Occupiers’ Liability Act applied.

The District Court held that provision of security services was not work which is directly a part or process in the trade or business of the Minister and the Minister had a duty as an occupier of land to protect entrants in respect of the state of the premises under the Occupiers’ Liability Act. Mr Klein was awarded damages of $100,187. The WA Court of Appeal allowed the Minister’s appeal, holding that maintaining government schools, including securing them, was to be treated as the trade or business of the Minister and Mr Klein’s work was directly a part of that trade or business. Mr Klein was then granted special leave to appeal to the High Court in relation to the construction of section 175.

The Court, by a 3-2 majority, revoked the special leave to appeal granted to Mr Klein. The minority would not have revoked special leave but would have dismissed the appeal. In 2004, the WA Parliament amended the Act to prevent section 175 curtailing the rights of workers to make claims against such persons independently of the Act. The majority held that the Parliament’s reliance on the correctness of Hewitt v Benale Pty Ltd, coupled with the closing of the class of cases in which issues of the kind raised in this case, make it inappropriate for the High Court now to consider whether to disturb the state of the law as stated in Hewitt.

———–

Leach v The Queen [2007] HCA 3, 6 February 2007

Northern Territory courts had not erred in deciding that a convicted murderer and rapist could be kept in prison for life without any chance of parole, the High Court of Australia held today.

On 20 June 1983, Mr Leach, armed with a knife, abducted two young women, aged 18 and 15, from a swimming pool and forced them to accompany him to a nearby gully. He cut off their clothing and used it to bind and gag the 15-year-old. Mr Leach stabbed the 18-year-old and, with the knife in her, bound and gagged and raped her. He stabbed and killed the younger woman. He stabbed the older woman again and left her fatally wounded. Mr Leach, who had already served a prison term for raping a woman at knifepoint in her home, was convicted of two offences of murder and one of rape. At the time, the mandatory sentence for murder was imprisonment for life. He was also sentenced for life for the rape of the 18-year-old.

The NT Sentencing (Crime of Murder) and Parole Reform Act came into effect on 11 February 2004. It provided for the fixing of non-parole periods for life sentences for murder imposed after that date. For people already serving life sentences, section 18 provides that the prisoner’s sentence is taken to include a non-parole period of 20 years, or 25 years if the prisoner was serving sentences for two or more murder convictions. However, the Supreme Court may, on application by the Director of Public Prosecutions, revoke the non-parole period and either fix a longer non-parole period under section 19(4) or refuse to fix a non-parole period under section 19(5). The Court may refuse to fix a non-parole period if satisfied that the level of culpability in the commission of the offence is so extreme the community interest in retribution, punishment, protection and deterrence can only be met if the offender is imprisoned for the term of his or her natural life without the possibility of release on parole.

On 2 March 2004, the DPP applied under section 19 for the Supreme Court to revoke the non-parole period fixed by section 18 and to take one of the options in section 19(4) or (5). Chief Justice Brian Martin made an order revoking the 25-year non-parole period for the two murder convictions and refused to fix a non-parole period. The majority of the Court of Criminal Appeal upheld that order. Justice Stephen Southwood would have fixed a non-parole period of 40 years which would have meant that Mr Leach could be considered for parole at age 64. Mr Leach appealed to the High Court, arguing that Chief Justice Martin failed to give effect to ordinary sentencing considerations when applying section 19(5), and that he had not shown he was satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Mr Leach’s culpability was so extreme as to require a sentence of life imprisonment without possibility of parole.

The High Court unanimously dismissed the appeal. It held that section 19(5) of the Act is not to be read as requiring a court to consider the exercise of some separate discretion after it has reached a conclusion that the prisoner’s culpability was so extreme that the community interest could only be met by life imprisonment. The word “may” in “may refuse to fix a non-parole period” confers a power to be exercised upon the court being satisfied of the matters described in section 19(5). Any disputed question of fact adverse to the prisoner are to be made to the criminal standard of proof (beyond reasonable doubt), but once the relevant facts are found a judgment would then remain to be made about the level of culpability and what the community interest required.

———–

X v Australian Prudential Regulation Authority [2007] HCA 4, 21 February 2007

Notices to two insurance company managers to show cause why they should not be disqualified from operating in Australia, which referred to evidence given by them to the HIH Royal Commission, were not in breach of the Royal Commissions Act, the High Court of Australia held today.

Z, an international reinsurance business based in Germany, is authorised by the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority to carry on business in Australia. X and Y are employed by Z as senior managers outside Australia. Z handed over documents to the Royal Commission into the 2001 collapse of the HIH Insurance Group and X and Y each travelled to Australia in 2002 to make statements and to give oral evidence. In 2005, Mr Godfrey, APRA’s senior manager, wrote to both X and Y seeking submissions on why APRA should not disqualify them under the Insurance Act as not being fit and proper people to act as managers or agents in Australia of a foreign insurer. The show cause notices stated that APRA’s preliminary view that each was not a fit and proper person was based on their involvement in certain arrangements entered into between Z and HIH, as revealed to the Royal Commission. X and Y’s lawyers responded that any decision to disqualify X and Y would be beyond power and would involve the commission of an offence under the Royal Commissions Act. They said such a decision would disadvantage X and Y, including the need to meet obligations to inform regulatory authorities in other countries.

X, Y and Z instituted proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia to restrain APRA from taking action against X and Y pursuant to the Insurance Act and for a declaration that APRA did not have the power to disqualify X and Y. Justice Kevin Lindgren and the Full Court on appeal rejected their submission that APRA could only disqualify persons holding senior insurance positions in Australia. Justice Lindgren and the Full Court also rejected a submission that the use by APRA or Mr Godfrey of X and Y’s evidence to the HIH Royal Commission contravened section 6M of the Royal Commissions Act. The High Court granted X, Y and Z leave to appeal in regards to section 6M. This provides that any person who uses, causes or inflicts any violence, punishment, damage, loss or disadvantage to any person for or on account of the person having appeared as a witness before a royal commission or for any evidence given by him or her before a royal commission is guilty of an indictable offence which attracts a penalty of $1,000 or one year’s jail. Justice Lindgren concluded that neither APRA nor Mr Godfrey has caused or inflicted any disadvantage on X, Y or Z on account of X and Y having given evidence to the HIH Royal Commission.

The High Court unanimously dismissed the appeal. It held that X, Y and Z could not demonstrate, within the meaning of section 6M, that APRA and Mr Godfrey proceeded “for or on account of” the appearance by X and Y at the HIH Royal Commission or any evidence they gave there. The Court held that Mr Godfrey was proceeding in discharge of the statutory powers of a regulatory nature conferred upon APRA by the Insurance Act. There was not the connection between X and Y’s attendance at the Royal Commission with the past or threatened conduct of Mr Godfrey or APRA that is captured by the expression “for or on account of”. Any disadvantage suffered by X or Y would not be “for or on account of” their attendance at the Royal Commission or the evidence they gave. Neither Mr Godfrey nor APRA victimised or proposed to victimise X, Y or Z in the sense required for the commission of an offence under section 6M.

———–

Commissioner of Taxation v McNeil [2007] HCA 5, 22 February 2007

Proceeds of a share buyback scheme are taxable income, the High Court of Australia held today.

Ms McNeil’s case is a test case affecting more than 80,000 taxpayers. The costs of the appeal were borne by the Tax Commissioner. In 1987, Ms McNeil acquired a parcel of St George Building Society shares, which in 1992 were converted into ordinary shares in St George Bank Ltd when St George changed from a building society to a banking corporation. St George’s profitability increased and in 2001 St George announced a buy-back of ordinary shares worth $375 million. For every 20 shares held, St George would issue one “sell-back right”, which was an option to oblige St George to buy back one share for $16.50, higher than market value. Ms McNeil held 5,450 shares, meaning she had 272 sell-back rights. The difference between the share buy-back price and the market price meant the value of Ms McNeil’s sell-back rights at the listing date was $514.

Shareholders could elect either to obtain legal title to their sell-back rights in order to sell their shares back to St George or to sell the sell-back rights on the Australian Stock Exchange. Ms McNeil made no election. This meant that St George Custodial, holding the sell-back rights as trustee, was obliged to sell those rights to merchant bank Credit Suisse First Boston. Shareholders could buy extra sell-back rights on the ASX, thereby increasing the number of their shares to be acquired by St George, so a market was created for the sell-back rights separately from the shares themselves. Eleven million sell-back rights were sold to CSFB on 20 February 2001 and these were then sold by CSFB on the ASX. Shareholders such as Ms McNeil who gave no directions about their entitlements were paid the proceeds of trading the sell-back rights on their behalf by CSFB and retained their shares. On 2 April 2001, Ms McNeil received her portion of the proceeds, $576.64. Of that amount, $62.64 was the increase in the realisable value of the sell-back rights and Ms McNeil concedes that this was assessable income as a capital gain.

The Tax Commissioner argues that the remaining $514 is also subject to tax, either as income or as a capital gain. Ms McNeil succeeded in the Federal Court of Australia and the Full Court, by majority, dismissed an appeal by the Commissioner. The Commissioner appealed to the High Court, which allowed the appeal by a 4-1 majority. The Court held that the majority of the Full Court erred in applying principles relating to the derivation of income. It held that whether money received has the character of income depends upon its quality in the hands of the recipient, not upon the character of the expenditure by the other party. The character of the sell-back rights held for Ms McNeil is not determined by her entitlement arising from St George’s decision to undertake a share buy-back. Her sell-back rights, which were turned to account on her behalf, did not represent any portion of her existing rights as a shareholder under St George’s constitution, but rather were generated by the execution and performance of covenants in the deeds poll establishing the buy-back scheme. The Court held that on the listing date, 19 February 2001, when Ms McNeil’s sell-back rights were granted by St George to St George Custodial for her benefit, there was a derivation of income by her, represented by the market value of her rights, namely $514.

———–

Leichhardt Municipal Council v Montgomery [2007] HCA 6, 27 February 2007

Roads authorities, such as councils, do not have an automatic liability for the negligent behaviour of employees of independent roadworks contractors, the High Court of Australia held today.

Leichhardt Council engaged Roan Constructions to upgrade a footpath on Parramatta Road in Sydney. Work was carried out between 7.30pm and 5.30am. Carpet was placed over a Telstra pit with a broken lid. As Mr Montgomery walked with two others on their way to his birthday celebration on 7 April 2001 the lid gave way and he fell into the pit, seriously injuring one knee. He sued both Roan and the Council. The claim against Roan was settled for $50,000. After a trial in the New South Wales District Court, Mr Montgomery was awarded damages of $264,450.75 in damages against the Council, minus the $50,000 already received. Both the District Court and the NSW Court of Appeal accepted that the Council owed Mr Montgomery a non-delegable duty of care and that that duty had been breached. The Court of Appeal agreed with the primary judge that, there having been negligence on the part of Roan’s employees, the Council was liable without any need for Mr Montgomery to show fault on the part of Council officers. The Council was granted leave to appeal to the High Court on condition that it paid the costs of the appeal.

The Court unanimously allowed the appeal. It held that the Council did not owe Mr Montgomery a non-delegable duty of care. A non-delegable duty of care when an independent contractor was engaged was not supported by statute, policy or recent High Court cases. Instead, the Council’s duty was the ordinary duty to take reasonable care to prevent injury. The NSW Roads Act did not contain any express or implied requirement that roads authorities undertake road construction and maintenance only through their own employees, and use of contractors was common.

The Court held that a special responsibility or duty to ensure reasonable care was taken by an independent contractor and the contractor’s employees went beyond the general duty to act reasonably in exercising prudent oversight of what the contractor does. It was implausible to impose a duty on the Council to ensure that such carelessness as placing carpet over the broken pit lid did not occur, regardless of whether the Council’s own employees were at fault. The Council had a duty to exercise reasonable care in supervising a contractor or in approving a contractor’s plans and system of work, but it was not automatically liable for the negligence of an independent contractor’s employees. The Court held that a line of Court of Appeal decisions to the contrary should be overruled.

As the appeal was confined to the issue of whether the Council owed a non-delegable duty of care, and there was an unresolved allegation of lack of care on the part of Council officers, the Court remitted the case to the Court of Appeal to resolve outstanding negligence issues.

———–

Z v New South Wales Crime Commission [2007] HCA 7, 28 February 2007

A solicitor appearing before the New South Wales Crime Commission was obliged to provide the name and address of a client and could not rely on legal professional privilege, the High Court of Australia held today.

In September 2003, the solicitor, Z, was summonsed to attend the Commission to give evidence in relation to an investigation into the attempted murder of M. Z’s client, X, had twice given Z certain information about M and, as instructed by X, Z had passed on that information to police. M was attacked in 2002, some years after X had consulted Z. When asked at a Commission hearing who had provided the information he had passed on to police and where that person could be contacted, Z declined to answer on the ground that the communications conveying that information were the subject of legal professional privilege. The Commission member conducting the hearing ruled that the communications were not privileged.

Section 18B(4) of the New South Wales Crime Commission Act provides that, if a lawyer is required to answer a question at a hearing and the answer would disclose a privileged communication with someone else, the lawyer is entitled to refuse to comply, but if required the lawyer must provide the Commission with the name and address of the person with whom the communication was conducted. The NSW Supreme Court dismissed an application for review of that ruling and the Court of Appeal refused Z leave to appeal. Z then appealed to the High Court.

In a 5-0 decision, the Court dismissed the appeal. Three members of the Court held that even if the communication of X’s name and address to Z were otherwise subject to legal professional privilege, the qualification in section 18B(4) gave the Commission power to require disclosure of the name and address. Two members held that, because what X told Z was for the express purpose of being passed on to the police, the communications were not privileged, not confidential and not for the dominant purpose of obtaining legal advice.

———–

Forsyth v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2007] HCA 8, 1 March 2007

The District Court of New South Wales had jurisdiction to hear and determine an action by the Deputy Commissioner against Mr Forsyth to recover a penalty for failure to remit income tax deducted from employees’ wages, the High Court of Australia held today.

Mr Forsyth was a director of Premium Technology Pty Ltd. Between 1 August 1997 and 31 May 1999, Premium deducted PAYE instalments totalling $668,845.97 from the salary and wages of its employees but failed to remit the full amount to the Commissioner. Directors are personally liable to pay penalties for failure to comply with the obligation to pass on the deductions. The Deputy Commissioner issued penalty notices to Mr Forsyth on 27 October 1998 and 15 June 1999. The unpaid amount was ultimately assessed at $414,326.45.

On 29 August 2001, the Deputy Commissioner instituted action in the District Court against Mr Forsyth to recover this money. Under section 39(2) of the Judiciary Act, state courts are invested with federal jurisdiction in all matters in which the High Court has original jurisdiction. Judgment was entered in favour of the Deputy Commissioner. Mr Forsyth had not objected to the District Court determining proceedings, but he appealed in the NSW Court of Appeal, claiming the District Court lacked jurisdiction.

Two Acts, both called the Courts Legislation Further Amendment Act, took effect in 1998 and 1999. The first Amendment Act introduced the current form of section 44(1)(a) to the District Court Act. This provided that the Court has jurisdiction to hear any action relating to claims of up to $750,000 which if brought in the Supreme Court would be assigned to the Common Law Division. The second Amendment Act reduced the divisions of the Supreme Court to two, Common Law and Equity, and the business of the Court was reassigned between them. Mr Forsyth argued that the District Court was deprived of jurisdiction when an amendment to the Supreme Court Rules in 2000 assigned to the Equity Division of the Supreme Court any proceedings relating to a tax, fee, duty or other impost levied, collected or administered by or on behalf of the State or the Commonwealth. (These matters were transferred to the Common Law Division by a 2004 change to the Rules.) The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal.

Mr Forsyth appealed to the High Court which, by a 6-1 majority, dismissed the appeal. It held that the jurisdiction of the District Court was to be identified by reference to the time the first Amendment Act introduced section 44(1)(a), not at 29 August 2001 when the action against Mr Forsyth was instituted. It held that when the first Amendment Act commenced, cases such as his would have been assigned to the Common Law Division of the Supreme Court. Therefore the action was within the section 44(1)(a) jurisdiction of the District Court. The Court noted that, even if Mr Forsyth had succeeded, a fresh action by the Deputy Commissioner could still have been brought in a court of competent jurisdiction.

BAQ Mediators Conference 2011

The BAQ Mediators Conference 2011 will be held at the Hyatt Regency Sanctuary Cove from 22-23 October.

Speakers at this year’s conference include:

- Ian Hanger AM QC

- The Hon Robert Fisher QC, Auckland, New Zealand

- Peta Stilgoe, Member, Queensland Civil and Administration Tribunal

- Andrew Crowe S.C.

- The Hon Justice Daubney

- Kathryn McMillan S.C

- Dr Anne Purcell, Psychologist

- Doug Murphy S.C.

- Michael Klug, Partner, Clayton Utz

- The Hon Justice May, Family Court of Australia

- Charles Brabazon QC, Retired Judge of the District Court of Queensland

- Wallace Campbell

To download the full program and registration form visit the CPD website.

QCAT Bar Update 2011

Date: Friday 4 November 2011

Time: 12.45pm — 1.45pm *Light lunch will be provided

Venue: Gibbs Room, Bar Association of Queensland

Presenters: The Hon Justice Wilson & panel members

Accreditation details: BAQ3111, 1 CPD point, advocacy strand

CLI Series: Criminal Law Reforms: One Year on

Date: Thursday 10 November 2011

Time: 5.30pm — 7.00pm

Venue: Banco Court, Supreme Court Complex, Brisbane

Presenters:

His Honour Judge Butler AM S.C., Supreme Court of Qld

Mr Peter Davis S.C.,

Mr Anthony Moynihan S.C., Director of Public Prosecutions

Accreditation details: CLI0311, 1.5 CPD points, non allocated strand

Pupils Session 8: Family Law

Date: Thursday 24 November 2011

Time: 5.30pm — 6.30pm

Venue: Gibbs Room, Bar Association of Queensland

Speakers: The Hon Justice Murphy and The Hon Justice Forrest, Family Court of Australia

Accreditation details: BAQ3211, 1 CPD point, non allocated strand

ABA Advanced Trial Advocacy Course

Date: 23-27 January 2012

Venue: Melbourne

Accreditation details: ABAC12, 10 CPD points, ethics and advocacy strands

Please click here Hyperlink: http://advocacytraining.com.au/

EXTERNAL EVENTS

2011 Mayo Lecture: Regulatory Reform

Date: Thursday 6 October 2011

Time: 6.00pm — 7.00pm

Venue: Townsville and Cairns

Accreditation details: JCU111006, 1 CPD point, non allocated strand

Court of Appeal 20th Anniversary Lecture

Date: Monday 24 October 2011

Time: 5.30pm – 7.00pm

Venue: Banco Court, Supreme Court Complex, Brisbane

Accreditation details: CA111024, 1 CPD point, non allocated strand

Criminal Law Conference

Date: Thursday 27 October 2011

Time: 9.00am — 5.00pm

Venue: Sebel and Citigate Hotel, King George Square, Brisbane

Accreditation details: QLS111027, 1 CPD point per hour, advocacy and non allocated strands

Please click here for further details http://qls.com.au/pd/events/111027

WA Lee Equity Lecture

Date: Thursday 18 November 2011

Time: 6.00pm — 7.00pm

Venue: Banco Court, Supreme Court Complex

Accreditation details: QUT111118, 1 CPD point, non allocated strand

Please email rsvplaw@qut.edu.au

2012 Environmental Law Enforcement Conference

Date: 3 — 7 July 2012

Venue: Dubrovnic, Croatia

Accreditation details: RP120703, 10 CPD points, ethics and advocacy strands

Please email Ralph RPDevlin@halsburychambers.com or Peter peter.kelly@halsburychambers.com for further information

Brigadier Ian Westwood AM was sworn in as the first Chief Military Judge at a ceremony in Canberra on October 3. He has 24 years of military law experience gained through full-time Army service. He was admitted to the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 1978 and appointed to the Australian Army Legal Corps in 1983. Brigadier Westwood, who resides in Canberra, is responsible for ensuring the orderly and expeditious discharge of the business of the Australian Military Court and managing its administrative affairs. He will also sit as a military judge on the court and report to Parliament annually through the Minister for Defence.

Brigadier Ian Westwood AM was sworn in as the first Chief Military Judge at a ceremony in Canberra on October 3. He has 24 years of military law experience gained through full-time Army service. He was admitted to the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 1978 and appointed to the Australian Army Legal Corps in 1983. Brigadier Westwood, who resides in Canberra, is responsible for ensuring the orderly and expeditious discharge of the business of the Australian Military Court and managing its administrative affairs. He will also sit as a military judge on the court and report to Parliament annually through the Minister for Defence. “It is critical to the Australian Defence Force’s operational effectiveness and the protection of individuals and their rights that we have a strong military justice system — one that not only underpins our discipline and command structures but also enables our personnel to work in a fair and just environment.”

“It is critical to the Australian Defence Force’s operational effectiveness and the protection of individuals and their rights that we have a strong military justice system — one that not only underpins our discipline and command structures but also enables our personnel to work in a fair and just environment.” Essentially, the trial procedures of the Australian Military Court are similar to those of civil courts exercising criminal jurisdiction. The general principles and laws of criminal responsibility as provided for within the Criminal Code (Commonwealth) apply in respect of Service offences prosecuted before the Australian Military Court, as do formal rules of evidence. The presumption of innocence to the accused applies as it does in a civil court which means that the prosecution is obliged to prove the case against an accused beyond reasonable doubt.

Essentially, the trial procedures of the Australian Military Court are similar to those of civil courts exercising criminal jurisdiction. The general principles and laws of criminal responsibility as provided for within the Criminal Code (Commonwealth) apply in respect of Service offences prosecuted before the Australian Military Court, as do formal rules of evidence. The presumption of innocence to the accused applies as it does in a civil court which means that the prosecution is obliged to prove the case against an accused beyond reasonable doubt.  Enhancing impartiality and fairness

Enhancing impartiality and fairness Self-employment obviates delegation (except to the extent that occurs between senior and junior and between barrister and solicitor). In consequence many of us tend to work excessively long hours and plan poorly for recreational and holiday time. The profession needs to redress this.

Self-employment obviates delegation (except to the extent that occurs between senior and junior and between barrister and solicitor). In consequence many of us tend to work excessively long hours and plan poorly for recreational and holiday time. The profession needs to redress this.  Candidly, I have breached each of these rules from time to time. That does not detract from their efficacy. Each ought be borne steadily in mind. Act now! You are a long time dead or divorced.

Candidly, I have breached each of these rules from time to time. That does not detract from their efficacy. Each ought be borne steadily in mind. Act now! You are a long time dead or divorced.