Author: Quentin BeresfordPublisher: NewSouth PublishingReviewer: Brian Morgan

Do you, like me, get annoyed when you are bombarded with gambling advertisements on TV, when you only want to watch the news or a particular sporting event live?

“Hooked” is a great name for a book of 345 pages which certainly explores the murky depths of the gambling industry in Australia and its association with major sporting clubs and with politics and the power it has exercised as a supporter of political parties and politicians as well as its ability to bring down politicians who don’t do as the industry demands of them.

The gambling industry is identifiable with a who’s who of Australian identities, such as Kerry and James Packer, numerous Prime Ministers, State Premiers, Ministers for Gaming, major sports and so on.

As I prepare this review, there is controversy over a leading Rugby League player who, it is rumoured, is looking to move to a breakaway team in order to be paid more than the $1m per annum that he apparently receives today. How can a sport justify paying its players such amounts and are they really worth such payments? Where does all that money come from, you might well ask?

Much of this book is devoted to the ongoing issue of people who are addicted to gambling. Over the years I have been involved professionally in a number of matters arising from stealing to fund a gambling habit; families losing their homes to gambling; and formerly successful business people losing everything because of the insatiable desire to gamble and I have felt overwhelming sadness and have experienced the feeling of frustration which arises from trying to help those who don’t seem capable of being helped.

Hooked provides a very in depth and comprehensive history, in particular, of the emergence of the poker machine phenomenon in Australia; how it has provided Clubs (including sporting clubs) and venues which have obtained these machines with huge windfalls of money; and how the casinos have thrived both with the pokies and the custom of their “high rollers”.

There are, I believe, strong similarities to the cigarette and tobacco industry in its heyday when we had the Marlboro man and others on our screens and smoking was portrayed as being “manly”.

As its name suggests, Hooked dives into the murky depths which we, in Queensland, have seen with the Star Casino group and its financial problems; stories of high flying overseas gamblers being feted in order that they might gamble large sums here; and the apparent failure of the checks and balances to prevent problem gamblers from being “hooked” and with similar histories with casinos in NSW, Tasmania and Victoria, in particular.

When you read Hooked, you will probably vaguely remember many of the events it describes of it but it still takes a great researcher to put it all together for the reader. Beresford has done this for every State of Australia as well as shining a light on the involvement, at the Federal level, of gambling giants who have been able to cause the rise and fall of Prime Ministers such as Julia Gillard. His chapter on our present Prime Minister will leave you shaking your head, no matter what political persuasion you consider yourself to be.

I like the names of several chapters, such as “The mafia comes to Australia”; “Vegas Down Under”; “The death of gambling reform” and “High rollers, private jets and bags of cash”.

I strongly agree with the statement of the author at pg. 214 when he says,

“If a tsunami of gambling ads blanketing mainstream media each year does not constitute predatory corporate behavior, then what does?”

I also agree with his observation at pg 290 that, “Both the major parties have turned a blind eye to the growth of Big Gambling, swayed by the surge in jobs, advertising and sporting revenue, by the state taxes that have been generated over the past 30 years and by the donations and lobbying”.

The author refers to many political identities, including the late Mervyn Everett from Tasmania, Deputy Premier, Attorney General, Queens Counsel, Senator, Supreme Court Judge and Federal Court Judge, whom he, perhaps, patronisingly, describes as a “former divorce lawyer” and suggests that Everett may have been corrupt.

I want to dispel that suggestion. Everett led me on many criminal and civil matters over a period of at least 10 years and I never saw nor heard anything to suggest that he was other than a devoted labour man who showed a real care for people. I had heard the story, referred to by Beresford, of Everett handing out money in the Parliamentary dining room but had never heard this ascribed as a reason to suggest he was corrupt. Those who told me about it at the time put it down as a harmless joke.

As an aside, I had dinner with Everett QC at his home, two nights before he died, just after his judicial career had finished.

He had returned to the Bar, the next day, as he rang me at 5.30 am to tell me he had been asked to lead me in another matter on which I was expecting to be briefed. The meal was cooked by him, using fish that he had caught that day. He was about to embark on studying for a PhD.

One cannot help but feel the power of the gambling lobby; its blinkered approach to high rollers being flown into Australia on Casino jets; passengers apparently being cleared through customs without any baggage or other checks; and the many stories now permeating our news of how this lobby is so powerful that its tentacles appear to have caught so many politicians and persuaded them to cease attempts to rein in the lobby’s influence.

In Queensland we have heard, at first hand, the stories about Crown and Star as late as this year. Had any other company or business suffered such financial issues, they would have been in liquidation but, as this study shows, the power of those behind the thrones of the gambling industry is enormous.

I thoroughly recommend this great analysis of the Australian gambling industry to all and, in particular, to our politicians whose heads remain in the sand.

Author: John Irving,Publisher: Simon & SchusterReviewer: Brian Morgan

I spent much of the time whilst I was reading Queen Esther thinking that I had missed something in that I found that it took right until its conclusion for me to understand it.

I often found myself returning to my study of English in my teens and, in particular, writers such as Charles Dickens. Dickens, the person and many of the characters in his books are referred to in Queen Esther, either directly or indirectly.

The main characters in this (fictional) story are a family of Jewish people. The parents and their daughters live in the United States. The approach to sexuality of the daughters is somewhat unusual for reasons which I will shortly explain.

Esther is one of the daughters. One of her sisters wants to have a child but does not want to conceive or carry it herself so Esther, after finding a suitable male to assist, agrees to do so.

The resulting son, James, grows up having two mothers but with virtually no knowledge of his actual father or, even, his birth mother. As a young adult, he decides to travel to Vienna, at a time when the United States is conscripting young men for Vietnam. James determines that, if he becomes a “father”, he will be entitled to avoid conscription into the US armed forces which, after several hundred pages, he achieves.

He spends much of the book exploring his Jewish heritage; trying to develop a relationship with Esther; and looking for someone prepared to have his child so he can avoid the draft and develop into a writer along the lines of Dickens.

He continues his struggle to identify himself, his relationship with the mother of his daughter, a lesbian to whom he is actually married, his own birth mother, his Jewish birthright and his aunt who had raised him as her child.

All these very loose ends come together at the conclusion of Queen Esther in a way which made me, eventually, appreciate the book much more than I had during the reading when I struggled to understand where it was leading, so much so, that I was tempted, at times, to abandon the whole project.

John Irving is not only a treasured novelist from a much earlier time but he won the Academy Award for best adapted screenplay for Cider House Rules at the 2000 Oscars. Indeed, I had read Cider House Rules, many years ago. Cider House Rules, published in 1985, is set largely at the St Clouds orphanage in Maine. The early pages of Queen Esther arealso set at St Clouds with both Irving and the reader recalling the fictional scenes from forty years earlier.

This is a serious work of fiction, rather than a book you could read in an hour on the train. In retrospect, I look upon it as a modern classic but some, like me, will struggle with it.

My major criticism is the pace at which it proceeds which, to my mind, was slow and cumbersome. Nonetheless, I invite readers to feel free to disagree.

Author: Dr. Bob BrownPublisher: Black Inc BooksPublished: 1 Oct. 2025Reviewer: Brian Morgan

I doubt that there would be more than a handful of people who have not heard of Bob Brown, perhaps, the best known Greens political identity that Australia has known.

As an ex-Tasmanian, I have a personal story to tell, to commence this review.

I was about to open the door to a bakery in a country town in Tasmania, some years back, when the door opened and there was Bob, with a genuine grin on his face, holding the door for me to enter. We chatted for about five minutes. He spoke to me by name. So far as I can recall, this was the one and only time we ever met which is not to say our paths had not crossed previously.

This chance meeting immediately came to mind as I read this book, the first time. The temptation is to think it is only a book about a well known campaigner and politician. I think it is far more than that. So, my review will have a different focus to many others.

The conservation movement has achieved many goals in Tasmania, some of which are generally applauded and others, denigrated. There is still debate about the flooding of Lake Pedder and the attempts to create the Gordon below Franklin power scheme as two examples. There is the ongoing furore as to logging of native forests, the trees which are harvested then being exported overseas.

My own personal and ongoing concern, which is mentioned by Bob in some detail, is the harm being done to the Swift Parrot, the numbers of which are decreasing apparently rapidly due to the loss of their habitat.

It is no wonder that the title of this publication is Defiance because it sums up the attitude of the Greens who, by way of one example, had been ordered not to trespass where massive old trees were to be harvested, were charged and bailed, yet continued with their protests and simply did not give in. One example of Bob’s sums it all up. He and another Green went into an area where they had seen Swift Parrots. The terms of the permission to log required that logging cease if Swift Parrots were seen. This rule was ignored. Bob and his companion were fined for trespass. The loggers who broke the law suffered no penalty.

I hear the beat of massive respect for First Nations People, in almost every chapter. Bob sets out some interesting history but the impression I gained was that he had and has a deep respect for First Nations culture.

Bob has been and remains at the forefront of challenges to activities to have them abandoned. He has not avoided arrest and has been imprisoned but, despite all this, has not been discouraged from his attempts to have proposed non-conservation activities abandoned and so has been a light and leader for his followers .

This book gives the reader a very realistic perspective on Bob and the Greens movement, particularly, in Tasmania but the latter part of the book identifies some of his actions on the mainland of Australia, in particular, his fight with Murujuga in West Australia where Woodside Petroleum sought to continue processing gas until 2070. And who could forget his convoy into Queensland to try to stop Adani?

Allow me to digress and comment on a chapter which I found rivetting, the subject of which concerns the World’s four most senior leaders (Putin, Modi, Xi Jinping and, in particular, Trump).

This chapter readily fits into the narrative of the rest of the book by providing a comparison between democracy and autocracy where the little person is ignored, imprisoned or worse. Bob compares the four leaders in a very intellectual and enlightening manner.

As you read this book, you are likely to agree with some of the actions taken in the name of conservation and shake your head at others, where you may disagree strongly with the efforts to stop a particular activity or you may agree wholeheartedly with those efforts. This is the one of the conundrums we experience in a democracy, don’t you think? Those who want something versus those who don’t.

My take on the Greens is that they are an important conscience for the rest of the population as their public comments make me, at least, reassess my attitude to a proposed activity. I have frequently had strong views on either side of the coin, namely, supporting their views or disagreeing with them but, unlike Bob, I have not felt sufficiently incensed to march, protest or be arrested. Nonetheless, I have often voiced my views, in relative privacy. Bob has been quite up front in expressing and explaining his points of view.

This publication casts a strong light on Bob and what drives him at an age (80) when most people are slowing down. From his early days as a GP, to meeting up with people such as Dr. Norm Sanders (said to be on Mt. Wellington where Bob was carrying out a protest), to his rafting activities on the Franklin River in the South West of Tasmania where he and his colleagues mounted a very successful campaign, to his continuing actions to prevent the logging of native timbers in Tasmania, Bob is now a well deserved legend in Tasmania.

That is not to say that he has not been active elsewhere. I have chosen to limit this review to some of his protests in Tasmania but Bob reveals in some detail other conservation activities on the mainland. And don’t forget that he was a Tasmanian senator in Canberra for 16 years and, prior to then, had been in the Tasmanian lower house for 10 years.

Finally I would like to reveal another anecdote of my dealings with Greens members. Some years ago, I was Counsel in a Royal Commission in Hobart where all people entering the Federal Court building, no matter who they were, had to have their bags checked and security screening carried out. As we returned from lunch, there was a long line of Green supporters and their leader (not Bob) who were in front of me. He quietly asked them all to step back to allow me to go to the front of the line even though I was representing people who were not seen as friends of the Greens.

Bob’s influence is very obvious in instances such as this. I have never heard him speak other than respectfully, even about people with whom he was in disagreement. One might say he has always played the ball, not the man (or woman).

You will enjoy this book immensely. Bob is a great writer who draws countless graphic word pictures. I have been to many of the Tasmanian locations to which he refers and his words remind me of the grandeur about which he speaks.

Author: Professor Henry Reynolds

Publisher: NewSouth Publishing

Reviewer: Brian Morgan

I have met some wonderful people some of whom have white skin. Some have been Indigenous Australians, others, Native Americans and others have been of various races and creeds. All Australians know that Ash Barty is an Indigenous Australian. And Indigenous Australians who play sport at a high level are appreciated by their teammates and fans as equal to or better than many of their teammates.

Today, it seems that an Indigenous Australian who excels at sport is “one of us” but such attitudes do not, necessarily, extend to Indigenous Australians who are not famous for their sporting or artistic prowess? What about the appalling treatment of Indigenous Australians who fought in the military for their country but were, on their return, treated as second class? And what about the way in which the owners and original occupants of this land were treated from 1788?

Nearby to where I live in Maleny, Queensland, is a wonderful reserve, the Mary Cairncross Scenic Reserve. We are blessed to have Uncle Noel, an aboriginal elder, attend the various functions and events held there and oversee a welcoming ceremony. One can walk into that reserve and feel an immediate sense of belonging to the land, not owning it but being a part of it.

So, whenever I have cause to read or think about our history and how we treated the (earlier) inhabitants of this Country, I feel inadequate. I look for more information to help me to understand the reasons behind the murder, displacement and inhumane treatment of those who were here before any European.

Professor Reynolds, whom I have met briefly, several times over the years, is an acknowledged historian of early Australian history.

There is much history which explains the UK Government’s attitude to its occupation of Australia which is largely unknown and would remain so except for this excellent work.

Most of us have come to understand that it was the first white settlers who believed that they were the “owners” of this Country and their treatment of those, already living here, was based on that principle but, by any standard, the treatment of those long term Australians was reprehensible and, I suggest, unjustified in law.

In order to gain a better understanding of this history, Professor Reynolds has, in his usual manner, meticulously, identified, studied and collated much of the early correspondence between London and the State Governors; looked at why those Governors behaved as they did; and has left us with a sense of disbelief that the new settlers sought to dispossess those who had lived here for many Centuries, by the simple means of claiming the land by posting a flag.

I warn you that, as a lawyer, you will find yourself shaking your head at the lack of logic and the wilful ignoring of legal advice received from renowned lawyers such as Emerich de Vattel who, as early as 1758, said:

“The conqueror takes possession of the property of the State and leaves that of individuals untouched.”

The author adds the comment that the citizen caught up in a war of conquest suffers only indirectly because it merely brings them a change of sovereigns.

This theme was continued by Chief Justice Marshall of the United States Supreme Court in 1833 when he said:

“The modern usage of nations, which has become law, would be violated; that sense of justice and right which is acknowledged and felt by the whole civilised world would be outraged if private property should be generally confiscated, and private rights annulled. The people change their alliance; their relations to their ancient sovereign is dissolved but their relations to each other, and their rights of property remain undisturbed”.

Imagine, if you would, a ship load of foreign sailors landing in England in 1770 planting a flag and declaring that their Country is now the owner of Great Britain.

So, what is the difference? The answers to this question are, I suggest, revealed by this book.

That question and its answers tend also to explain the differing attitudes towards what we have come to call Australia Day, the 26th January, and why the traditional owners of Australia do not think of it as a day to rejoice.

Other countries were “settled” (my term), peacefully, and with the use of treaties. So why did this not occur in Australia? An Australian lawyer writing in 1847 declared:

“Successive Secretaries of State … have repeatedly commanded that it must never be forgotten ‘that our possession of this territory is based on a right of occupancy’.

A ‘right of occupancy’! Amiable sophistry!…….on what grounds can we possibly claim a right to the occupancy of the land?”

I suggest that this statement is as apposite today as it was then.

I do not find myself able to accept all the conclusions expressed by Professor Reynolds in this book, in particular, the criticisms of Sir Samuel Griffiths who when, as Attorney General of Queensland and later, is accused of being complicit in killing of Aborigines and personally responsible for it. I think that this accusation is made on the basis of his membership of Cabinet and later as Chief Justice of the High Court but, to me as a lawyer, this is drawing a long bow.

This book will, I am in little doubt, better inform you. It will require and allow you to re- consider your position in relation to the whole question of Aboriginal rights in Australia and the legality of their treatment even extending to the present time and it will help you to gain a better understanding that, if the occupants of the land were warlike, it was for the obvious reason of the need to protect their own land and culture. On the other hand, as the author suggests, if someone invaded our Country and sought to take it by force, what would we do? Surely, we would do our best to defend our rights.

Author: Jennifer DownPublisher: Text PublishingReviewer: Brian Morgan427 pages

Some people never have a chance in life. They are born into a dysfunctional family; for one or other of many reasons, they end up in foster homes; they become addicted to alcohol and/or drugs at a young age; they drop out of school; and, by early adulthood, they have probably lost any chance of having a successful life.

Bodies of Light, a challenging book, is a story of just such a girl. She was clearly intelligent; was able to complete her schooling; she gained entry to University; but it didn’t take long for her past and her addictions to catch up with her.

Imagine losing three children in succession to what, today, we would call Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. And then to be charged with their murders in circumstances where there would seem to have been no evidence of a crime but, rather, an inordinate focus on the coincidence that the three babies died, two of them when her husband was also home and the third when she was alone.

I found this one of the most confronting stories that I have read in a long, long time. I could not help but think of the many children for whom I had acted for (and against some, as well) and how most of them were never able to escape their past.

The author has received a great deal of praise for her writing, praise with which I agree. She has written a tear jerker but one which has the additional dimension for lawyers of causing us to feel frustrated, helpless, angry and perplexed all at the same time.

As far as I know, this is a work of fiction but it is so close to examples that I have seen that my reaction to it was to assume that it told the story of a particular person. Perhaps, it is part of the gift of the writer to induce us to believe that their imaginings amount to a factual account of an unknown person.

Two days ago I was at a luncheon at Point Cartwright near Mooloolaba and met a young family for the second time. They have a non verbal daughter of about 8 years old (my estimate) who needs full time care, which she receives. I had almost completed reading this book and could not help but think that this young one also has little chance in life for quite different reasons.

Be warned. This book will challenge you and, if you work in the field of children, it will, I suspect, cause you to think more carefully about some of your clients and how life has dealt them such a cruel hand.One reviewer has described this as “a novel with immense dignity and heart”. I wish I had thought of those words as they sum it up in a nutshell.

Brian MorganMaleny22 March 2022

Author: Luke StegemannPublisher: NewSouth PublishingSoft Cover, 284 pages

I came to read this book with no idea as to what it would contain. For nearly half of it, I remained unsure of where it was going.

But, suddenly, all was made clear. This is a book which draws a comparison between the treatment of Aborigines by white settlers during Australia’s early days of white settlement and the similarly indiscriminate murder of 170,000 Spanish during the insurrection which commenced in 1936.

There are many similarities demonstrated by the author.

I have had the privilege of travelling in Spain as well as speaking Spanish. On one occasion, I stopped to inspect an unusual building which was very close to a cemetery. The building turned out to be an “hórreo”, or grain shed built on stilts above the ground in order to provide ventilation, but I spent a long time examining the cemetery, as it was evident that it was built on a number of levels. That is, it seemed to me that there were earlier graves beneath the monuments which stood out so graphically on the top level.

This turned out to be one of the mass graves referred to in the book over which new crypts have been erected.

The author recites how he and his daughter visited the San Fernando cemetery just outside Seville in 2017 to explore or learn about the mass graves and cemeteries.

By comparison with the murdered Spaniards, the author refers to the wanton slaughter of Aborigines, domestic servants, men, women and children and how their remains were left where they died, thus making it very difficult for anyone to estimate the number who were killed and also, perhaps, showing the ultimate sign of disrespect for these victims.

There are other comparisons that Stegemann makes between the two sets of historical circumstances. Gang rapes of young Spanish girls, forced raping of Aboriginal girls and the indiscriminate murders in both countries form only part of the events.

The Spanish continue to disrespect this aspect of their past in that, if construction work uncovers, say, Roman ruins, the work must stop for a cultural assessment. But, if remains appear from a grave from the 1930’s uprising, the approach has been to ignore it.

He makes a comparison with Australian farmers who simply re-bury aboriginal remains upon which they might come.

I quote the powerful words of the author which I read as I was thinking to myself of the immensely strong feeling of death that I have had when visiting the battle site of Culloden in northern Scotland:

“The tides of blood recede with astonishing speed. So it is in Andalusia: sold relentlessly as a folkloric playground, tourist narratives give no hint of the damage done by psychopathic soldiers in town after town still within living memory”.

I think that the author correctly summarises the thinking behind the treatment of Aborigines in Australia and the murders in Spain when he says:

“Where a strong racial element prevailed in Australia, in Spain it was class, and politics”.

This is a confronting book which is appropriately named. I have heard and read much of the mistreatment of Aborigines in Australia, but I knew far less of the killings in Spain.

There are comparisons which can readily be made, but I think that, from the graphic details contained in this book, we can more readily appreciate how human lives counted for so little and how the deaths or, more correctly, the murders of innocent people continue to be ignored in Australia, as also in Spain.

Edited and Annotated by Philip AyresPublisher: Federation PressHard Cover, 392 pages

Recently I had the pleasure of reviewing the third edition of Jesting Pilate. This book that I am now reviewing describes another part of Sir Owen’s life, ie, his time in the United States during WW 2.

Sir Owen was appointed by the Australian Government to represent it at the highest level in the United States, five months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbour.

My first observation is the frequency with which Sir Owen kept in communication with his brother judges on the High Court. I have heard it said that his Court was very collegiate and although we are not told the content of his communications, their frequency bespeaks continuing close friendships. I noted that, on a return trip to Australia, within a day or so, he called on his brother judges.

The next observation I make is just how busy and demanding was this job. There were almost daily lunches, cocktail parties and dinners which seemed an accepted method of mixing during these times of war. But, as well, almost every day (including weekends), Sir Owen called on people and/ or had a multitude of visitors. He frequented the White House and had many meetings with the President. It seems evident that he quickly learned the art of diplomacy. There was no doubt that he was trusted and told things in confidence, a confidence which he did not abuse.

Two of his major tasks, which remained ongoing throughout his period in the United States, were to push for greater lend lease facilities especially aircraft to be provided to Australia and to gain an understanding from time to time of the thinking of the various leading world figures with whom he came into contact in order to keep the Australian Government well informed. Equally importantly, it was expected that he would try to influence that thinking towards the line of Australia’s views and policies.

When Sir Owen was asked to take leave from the High Court, he accepted only on the condition that his communications would be direct with the Prime Minister of Australia, allowing him to bypass Dr. H.V Evatt, the Minister to whom otherwise he would have reported. He and Evatt had previously sat together on the High Court. I think it is fair to observe that Sir Owen did not have a great liking for Dr Evatt. Indeed, my impression is that, at times, Dr Evatt seemed, intentionally or otherwise, to be trying to undermine Sir Owen’s work in the United States. Again, on a return trip to Australia, the Prime Minister agreed to reduce or remove the opportunity for Evatt to limit Sir Owen’s work.

In reading these diaries, which were never intended to be published, one cannot help but appreciate the added pressure on Sir Owen of the presence of his extended family with him. There are references to family illnesses getting him up early, notwithstanding that he had a full day of meetings. There were also many visits to hospitals whilst one of his sons was being treated for asthma and probably pneumonia. Another son had a serious eye condition. Sir Owen had to balance his heavy official workload with the needs of his continuing close relationship with his whole family.

Sir Owen was not regarded as having a great sense of humour on the bench but he clearly had one as demonstrated by his comment during a discussion about the reform of a moral delinquent that such stories reminded him “of the cannibal chief who lost his teeth and became a vegetarian”.

My final observation is how Sir Owen went out of his way to meet and mix with colleagues in the legal profession during this time, ranging from law professors to judges both in the United States and, in particular, neighbouring Canada. He also made it his business to meet governors and politicians, not only in Washington DC where he was based, but in other States as well. Within a day of returning to Sydney during his United States sojourn, he was at the Courts!

Oh and, on his final return to Australia by ship, what did he read but one textbook on Torts and another on Conflict of Laws, again, demonstrating that he continued to regard himself as a student of the law (a reference to which was in my earlier review of Jesting Pilate).

One could write many pages about this book. Because I have a deep interest in history, it was particularly interesting to me. But anyone reading it will, I believe, be struck by the “names” who regularly appear, about whom we know so much and who, in the next generation, remained family names in this country, at least, and whom we have come to know and respect in legal, vice regal and political circles. From Churchill to FDR, and on to Gromyko, whom the book describes as one of the most able and long serving USSR diplomats (and whom many of us will remember from subsequent news reports of his activities), the Diaries are full of the “who’s who” of the world at that time.

This is a book which needs to be read over several days to give the reader the opportunity to digest its contents. I found it of immeasurable interest. I hope you will too.

Author: Professor Raina MacIntyrePublisher: NewSouth PublishingReviewer: Brian Morgan

At the outset, let me say that this Vaccine Nation is a great book, written by a highly skilled doctor and academic who has what some people call, “the gift”, meaning the ability of writing in a way which is understandable to people from other vocations.

Anyone thinking of “vaccine” might be forgiven for immediately jumping to COVID but don’t forget measles, polio, smallpox, Ebola, monkey pox and tuberculosis which are but some examples of contagious diseases that require a vaccine to control or, hopefully, eliminate them. The author informs us of these as well as many other diseases that are perhaps not as well known.

Let me digress for a moment, to focus on the author. As a barrister, one sometimes finds oneself needing an expert in a field, let’s say physics. The expert may have eminent qualifications and be widely published. But does that person have the skills to translate their understanding into one which a Court or jury can also understand? Frequently, in my experience, they don’t.

This author does.

Her prose is eminently understandable. Where she uses words with which we are likely to be unfamiliar, she immediately explains them in simple terms. She does not talk just in academic words but her style of writing is such that this work was readily understandable to me and, therefore, I am sure, to other lawyers.

MacIntyre does not confine her discussion to Australia but focuses on disease outbreaks throughout the world in economically advanced countries like the United States and, on the other side of that coin, in developing countries, as well.

A little of MacIntyre’s own life’s experiences are injected (pun intended), to make a point, such as the way she has been disrespected because she was not born in Australia and her reaction when her infant son contracted a disease and she, as a mother, seems to have partly blamed herself for not having had him vaccinated. Wouldn’t we all apply the “What if” concept if it were one of our children? MacIntyre also refers to some of her own experiences together with those of adult members of her family, in a way which demonstrates that her worldview extends to real life as well as to her academic training.

MacIntyre reminds us that, in the early days of COVID, Dolly Parton gave funding towards the development of a Moderna vaccine and even adapted her well known song “Jolene” to “Vaccine” which was sung as she received her vaccine.

I received AstraZeneca as my first vaccine against Covid. Since then, I have received annual injections of Moderna. Do we know the difference between them and why the former is no longer approved in Australia? Read this book and you will quickly find out.

Do we have any idea of how much continuing research goes into even the influenza vaccine which we are encouraged to have each year?

These are just two examples of issues which the author explains plainly and simply so as to improve our understanding that a vaccine is not developed overnight; it is subjected to rigorous testing which does not cease when it is sent to the market; and how, with viruses which mutate, such as Covid and influenza, the fight to keep ahead of the latest variants of the disease, continues.

Just in case you are wondering whether to continue with Covid boosters, perhaps, the following observation might help your decision making.

MacIntyre points out that a recent study found that 5.4 percent of people in Australia are living with Covid. She goes on to point out that employers may start caring when the productivity of their employees drops due to workers being affected by Covid but regrets that so much denial and silence remains towards both the short and long term consequences of Covid. (I deliberately paraphrase her comments as my review copy of the book is a pre publication version and therefore I prefer not to appear to be quoting directly from it.)

Earlier, MacIntyre spends most of a Chapter pointing out the risks and consequences which may arise from contracting Covid. These include the misdiagnosing of conditions and, as a result, mistreating them, heart attacks and strokes. But do we ever hear of these?

And what of the anti-vaxxers? A lawyer could say, after reading this book, that, in her own quiet way, MacIntyre has systematically and clinically dissected their largely irrational rants but as I, myself, have seen, many times, when trying to dissuade an antivaxxer from a particular point of view, you would have more luck talking to a brick wall. MacIntyre, I think, seems to have had the same result where she has taken the time over the years to try to engage with such people; point out their errors with logic, demonstrated data and calmness; and got nowhere.

Whilst Vaccine Nation is not written for lawyers or by a lawyer, it is one which will readily fill in many gaps in our knowledge and understanding of diseases, disease control, topics such as “herd immunity” and vaccines. Vaccine Nation is a model for ease of understanding by people who do not have the professional training of the author. I intend to purchase a copy for my daughter and for each of my sons and their doctor spouses.

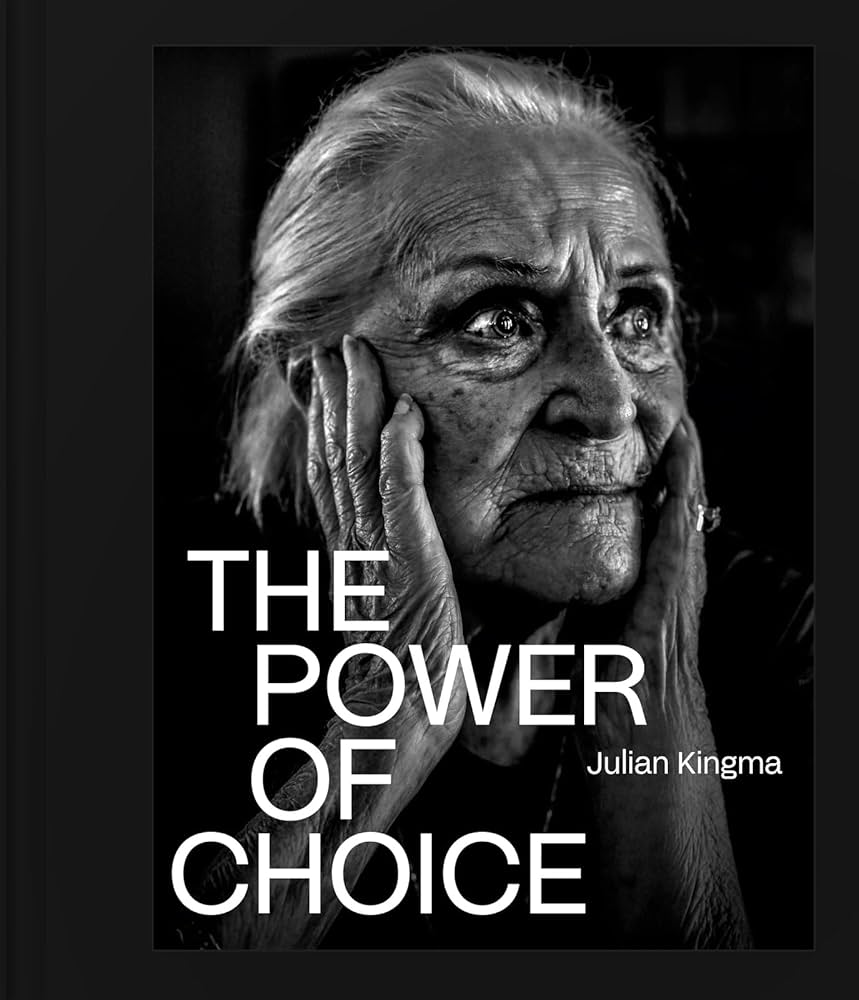

Author: Julian Kingma with Steve OffnerPublisher: New South BooksReviewer: Brian Morgan

This is a book which explores VAD or voluntary assisted dying as told through the eyes of a number of terminally ill people who chose this means of ending their lives.

Upon turning over the front cover, I was presented with an article by Andrew Denton, a person whom I have never met but for whom I have had a high regard since his days conducting interesting and intelligent interviews on ABC television. Later, he has, I believe, become a euthanasia advocate which, perhaps, explains why he has made this contribution.

He wrote a 6 page article, headed “To Life”.

His article was followed by one headed, “Where is the song?” written by the Tasmanian author, Richard Flanagan, which includes a story involving VAD and his own brother in his role as a Country GP assisting the terminally ill.

Those articles open the door for ten thoughtful stories, accompanied by appropriate photographs, all concerning the struggles and thoughts of VAD candidates, their families and those involved in the medical profession with the VAD process.

The titles of these stories are: “A good death”; “The power of choice”; “Suffering”; “Clearing the hurdles”; “The carers”; “It can ask a lot”; “The guiding lights”; “How do you say goodbye?”; “The final word”; and “The last intimate thing”.

The book concludes with a short explanation of the VAD process which varies somewhat between the States; a timeline of the introduction of VAD laws in each State; a discussion of how they work; and a glossary of terms used and whom to contact.

I say this, in relation to all contributors, that each of them , in their own way, shines a specific light on the decisions made by their loved one, reveals the support offered to and by the person dying and gives us unique opportunities of seeing, almost at first hand, how VAD can bring comfort and peace in the face of imminent death of a terminally ill person terminally.

I know, at first hand, having spent much time with a friend who was terminally ill with pancreatic cancer and had no family in Australia, that they seem to give us courage, whilst we are trying to be supportive of them in their final days.

The Power of Choice displays their stories in words and in dignified and beautiful photographs.

One photograph, in particular, is worth mentioning as it demonstrated to me a patient doctor relationship somewhat different to the norm and the accompanying article explains why this is so.

Here we have a doctor removing her shoes and sitting on a lounge, next to her patient as they discuss the VAD process.

“Finding a connection is important” (Dr. Bu O’Brien agrees): “It is such an intimate thing when you are doing assessments and potentially administering the VAD medications”. (text page 91).

The photo accompanying this story shows the doctor and her patient sitting next to each other with the doctor’s arm around her patient’s shoulder.

Through The Power of Choice , we can recognise why this process is not every doctor’s cup of tea and how much it must take out of them, psychologically, but, also, how many of them are comfortable with their involvement in a process of choice, that is, the choice of the patient whether or not to die at a time and in a manner of their choosing.

I had subconsciously wondered whether everyone who was accepted for VAD went through with the whole process. Some of the stories demonstrate that many people obtained the chemicals with which to end their lives but did not use them immediately, or, I infer, at all, as having the means of doing so, in some cases, gives them the comfort to delay taking the final step. There are many references to the relief felt by some terminally ill people through knowing that they can use the chemicals, if and when they want to, once they are at hand.

There are some references to palliative care which, until VAD, was the process of permitting people to die with some degree of dignity and which remains the process of choice for many. Perhaps, some of us have been told to say goodbye to a dying friend in palliative care as he or she will not be with us in the morning to find that the person has, indeed, died overnight.

This is a wonderfully illuminating picture and word exposure of voluntary assisted dying, the process; why some people with terminal illnesses choose to use it; the involvement of family and loved ones in supporting the decision; and the extent to which close friends, spouses, etc, come to accept the decision to take the opportunity to die with one’s loved ones by their side.

This is a most thoughtful and appropriately named book.

Author:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Peter MonteathPublisher:Â Â New South Publishing

This recently published book is an historical account which presents a most accurate picture of the fight, predominantly by the Australian and New Zealand armies, to try to repel the German invasion of the island of Crete in May 1941.

Over the years, I had heard quite a bit about this battle from the point of view of people who lived in Crete, at the time. This book, however, gives a much more detailed and vivid picture.

The title comes from the name given to the location of one of the greatest battles where the Anzacs shone most brightly.

One could not say that this is background to the book, as my impression is that it is a major facet of it, but the Australians and the New Zealanders, particularly the Maori soldiers, demonstrated that, in ground skirmishes, the bayonet was every bit as successful as the German Stuka dive bombers were in the air.

The author presents a graphic picture of how the Maoris used the Haka very effectively prior to going into close battle with the German troops and how the bayonet was both psychologically and physically such a useful weapon at short range. Often their enemy turned and ran to avoid the bayonet-wielding Anzacs.

It is not difficult to imagine the fear that the Anzacs, themselves, must have felt when they were subjected to paratroopers descending on them, all the while also being attacked by the Stuka dive bombers. Most, if not all, anecdotes that involve these aircraft make mention of the terrible noise that they made as they descended at high speed to strafe the unfortunate people on the ground. What I did not know, until reading this book, was that this noise was caused by a device specifically installed in order to intimidate. I saw resemblances between the Haka and these “Jericho Sirens” as, in its own way, each was intended to cause the same result in their enemy.

I will never again look at a Haka, prior to a sporting event, without gaining even more respect for it.

The book follows the fight for Crete which, history shows us, was won by the Germans. Many Anzacs were left behind, some to become prisoners of war and others to live in the forest either to try to find their way back to friendly territory or, in many cases, to later surrender due to poor health, lack of food etc.

I read this as an e-book which proved to be a convenient way of accessing and enjoying the book.

It is extremely well written, by which I mean that the style makes for easy reading, the content is detailed without ever becoming boring and the author’s tactic of following the history of a number of the officers and other ranks, both through the battle for Crete and into later life, provides additional perspective. As well, the book is written with many references to German strategy of the time, an account of the mistakes made on both sides and, perhaps, identifying how errors on the Anzac side contributed greatly to the defeat at a time when, we can now say with hindsight, victory was in the Anzacs’ grasp until the baton was dropped.