On 24 March 2022, the Honourable Justice Glenn Martin AM was appointed as the Senior Judge Administrator of the Supreme Court of Queensland. Justice Martin, a Past President of the Bar Association and current President of the Australian Judicial Officers Association, presented the below paper to the Annual Conference of the Bar Association of Queensland on 27 March 2022.

The use and abuse of written submissions has been the subject of dozens of articles and presentations at conferences like this for decades. Is there anything new left to be said? Probably not. Then why have a session at all on this topic? Because counsel are still wasting the opportunity to have their arguments put, without interruption, to the court. In oral submissions you might be the subject of cross-examination from the bench and, sometimes, feel that you’re not able to get your point across. That ability is manifestly available in a written submission.

I’m going to approach this topic under four headings:

- Why is the written submission overtaking the oral submission at an increasing rate? Because it often helps when considering how you will frame a submission to consider why it’s being put in writing.

- When are written submissions the superior means of persuasion?

- What are the basics of a persuasive written submission?

- How can you blend the written and the oral so that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts?

Why is the written submission overtaking the oral submission at an increasing rate?

There are many practice directions or rules of court or conventions which mandate or strongly encourage the use of written submissions. I’m going to be talking to you today about the use of submissions at the trial level. There are differences of focus and detail which separate trial submissions from appeal submissions and from those which are provided on applications. But, if they are done well, then they will all contain a core of exposition and analysis.

Sometimes it assists when drafting submissions to bear in mind how we have reached this state. While the provision of written material was well advanced in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in Canada from the beginning of the 20th century, the provision of submissions here was almost unknown only 40 years ago.

“… you should not expect to have an adjournment for some time in order to prepare written submissions. Most judges will expect you to commence your submission immediately.”

There are, I suggest, seven reasons for the requirement most courts impose or request for the provision of written submissions. I’ll deal with them very briefly.

The first is the time pressure on judges. I am not aware of any jurisdiction in which governments are delighted to increase the number of judges available to hear trials. They require the courts, like many other parts of society, to do more with less. The courts also impose time limits on the delivery of judgements. Around Australia the usual protocol is that a judgement should be delivered within three months of the last day of the hearing. That is not unusual. And written submissions are seen, correctly in most cases, as assisting the judge in writing the decision.

The second is that technology has made it so much easier to do this. In 1982, there were no word processors. Barristers did not rely on an Apple or a Windows computer but on an IBM or Olivetti typewriter. Easier, though, does not always mean “better”.

Thirdly, at least in the superior courts, reliable transcript is readily available. This has led to both counsel and solicitors taking fewer notes during a hearing and waiting for the transcript to be available. It is also led to a much greater insistence on accuracy so far as references to exchanges in examination or cross examination are concerned.

A fourth issue is the inexorable move from common law principles to principles embedded in statutes. It was once possible to argue a contract or a tort case without referring to a statute. The broad principles were known and reference would be made to leading authority. The reluctance of legislators to leave anything alone has meant that many of those principles now find themselves being expressed in excruciating detail in statutes. Reference must be made to sections with many subsections and sub subsections and that can be almost impossible to do in an oral presentation. Judges are much more likely to understand a submission where the relevant section is inserted into the written submission.

Fifthly, the diet of trials fed to judges used to be leavened with some simpler cases. They might only last a day or two and could be dealt with adequately in the final oral address of counsel. Those cases are rare birds now. Mediation and other means of alternative dispute resolution has meant that the cases which are listed are the most difficult or most complex cases which remain intransigently incapable of resolution. The more complex the matter, the more helpful a written submission is.

The sixth point is that a generation of counsel and judges have grown in the profession while these changes have been being made. The expectation that a barrister will give a final oral address at the conclusion of, say, a three-day trial is greeted by some with an onset of nervous perspiration and a general desire to be somewhere else.

Finally, the appointment of judges from outside the traditional pool of the senior bar has resulted in some judges who are more comfortable with receiving arguments in written form.

“Allow me to remind you that a written submission is just as much advocacy as oral argument or cross examination. It is all about persuasion.”

I have discussed with a number of the judges on my court the fact that I was going to be speaking to you today on this topic. One response, apart from the universal expression of pity for me, was this: Counsel should not expect that they will be allowed to provide written submissions in a trial which is relatively simple and short. There are, of course, not many of those in the Supreme Court but where the evidence concludes in two or three days then you should not expect to have an adjournment for some time in order to prepare written submissions. Most judges will expect you to commence your submission immediately. Wise counsel will enquire at the beginning of the trial as to the judge’s expectation with respect to presentation of addresses.

When are written submissions superior?

The occasions are four in number:

- a lengthy trial;

- a detailed examination of complex facts / expert evidence;

- a detailed examination of complex legislation;

- when a reserved decision is inevitable.

What are the basics of a persuasive written submission?

There are hundreds of papers and articles published in this country and elsewhere which deal with the construction of a written submission. There are dozens of books – mostly from America – which do the same thing.

I am not going to attempt, in the time available, to cover the entire field. I want to deal with a few matters – some more important than others – which may assist you in the difficult task of composing a compelling submission.

Allow me to remind you that a written submission is just as much advocacy as oral argument or cross examination. It is all about persuasion.

You will be more likely to be successful – assuming you have a case which allows you to be successful – if you always bear that in mind.

Do not fall into the trap of putting every last indefinite article, punctuation mark and rhetorical device into the written document. It is not a script. It is not a journal article. It is not a doctoral thesis. It is an implement. It is a tool to be used by the judge when he or she is working on the judgment. It was put this way by one eminent English Judge: you should aim for the middle ground – somewhere between a text message from a teenager and a brief for the US Supreme Court.

It is a document which you wish to have the judge pick up and use it with confidence. It is not a document which will have the judge flipping backwards and forwards in order to find where particular important matters are dealt with.

Always remember:

You are trying to persuade the judge.

- Not your client.

- Not your solicitor.

- Not your opponent.

The judge.

Let me start at the very beginning.

It is not unusual to receive, after a trial has concluded, a written submission which commences with the full title of the matter and then has the bare heading: “written submission”. This is obviously to assist those judges who cannot tell the difference between an oral and written submission. It also has an air of mystery – whose submissions are these? It often seems to happen where there are more than two parties involved. Please identify the origin of the submissions. The plaintiff’s, the second defendant’s, the first third-party and so on.

“It also has an air of mystery–whose submissions are these?”

During trial, conventions often arise as to the manner in which particular parties are referred. It is always better to refer to parties by their actual names rather than their position on the court heading. Any reader is more likely to comprehend an argument better if the reader is provided with a consistent description of the relevant party. And keep it consistent – if a party has been referred to away during the trial, don’t change the description when you come to write about it.

So, you’ve told the reader on whose behalf the submission is made. You want to make the reader continue to read it and to comprehend.

A shorter document is easier to comprehend than a longer document. There is no prize for the heaviest submission.

One of the best expositions of the elements of clear writing was set out by George Orwell in “Politics and the English Language” published in 1945.

In discussing clarity of language he provided the following rules which, he said, would cover most cases:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

You will always be assisted if you bear those in mind.

The admonition that: if it is possible to cut a word out then you should cut it out carries across to the citation of authority. You should always remember:

“…if it is not necessary to refer to a previous decision of the court, it is necessary not to refer to it. Similarly, if it is not necessary to include a previous decision in the bundle of authorities, it is necessary to exclude it.”

R v Erskine [2009] 2 Cr App R 29, per Judge LCJ at [75]

May I take this opportunity to remind you that there is no need to demonstrate a principle by reference to decisions commencing in the 18th century and listing those cases which have dealt with that principle. The rule of thumb is that when referring to a principle or exposition of law you should only refer to the authority which is the most recent and from the highest court. If the High Court has pronounced upon a subject, then there is no need to refer to decisions of intermediate courts of appeal which have followed it. If the High Court has not dealt with a particular matter then, of course, you would refer to an intermediate appellate decision. There is no need to clutter a submission with a recitation of a long list of authorities all dealing with the same point. And it will be a rare day when you cannot find an appellate decision on the topic you’re discussing.

A submission not only needs to read well, but it also needs to look good. There should be some white space on the pages. There should be headings which are consistent with the issues to be determined. The paragraphs should be numbered and never in the decimal style. Use the same conventions as are used in legislation, i.e., number, letter, roman numeral etc.

“Set out what some call an “overview statement” which tells the reader what the case is about, who did what to whom, the major issues and your position on them.”

Do not be afraid to incorporate diagrams or plans or maps. It will not be necessary in many cases. But in cases involving, for example, complex corporate relationships a diagram demonstrating the hierarchy can be very helpful. In a case for family provision where there are numerous relevant family members then a family tree can explain the relationships much more quickly and much more efficiently.

I come now to the one thing that I want you to remember about this subject – the importance of context.

Whether your submission is for an application, a trial, or an appeal, the judge may not come back to it for some months. In the trial division, the judge may have heard other civil or criminal trials after your trial concludes, and before writing can commence.

So, remind the judge of what it’s about. Don’t just leap into an analysis of the law or the facts.

Put yourself in the position of the reader, i.e., the judge. The judge hasn’t been able to turn his or her mind to it for some time. Set out what some call an “overview statement” which tells the reader what the case is about, who did what to whom, the major issues and your position on them. This should take up no more than one page. And this process represents a fundamental principle of persuasive submission writing: put context before details.

The overview statement is important because it provides a roadmap for the rest of the submissions. It provides the context for those submissions and allows the judge to better absorb and understand the details which follow.

In that introduction you begin by persuading the court of the rightness of your client’s case. Tell the story in human terms. You are wanting to grasp the judge’s attention and that is best done by capturing the essence of what the case is about and why your client should succeed.

In your introduction you will state the key issue or issues on which the trial turns. This is a task which requires careful attention. You do not want to descend into complex particularity, nor do you want to state the issue too broadly.

So, start with a sufficient but simple picture of the facts which provides a context to the issues and a preview of what is to come in the balance of the document.

“Submissions should be issues-based because judgments should be issues-based.”

There are four principles the observation of which will lead to a more effective document.

Principle 1

Readers will absorb information better if they understand its significance as soon as they see it. Before providing detail, provide a context or framework that allows them to grasp the relevance of the detail in the organisation that binds them together.

You do this by:

B

making the structure of the information explicit

C

beginning with familiar information before moving to new information

Principle 2

A reader will absorb information better if its form (its structure and sequence) mirrors its substance (the logic of the analysis or the theme of an argument).

Submissions should be issues-based because judgments should be issues-based. Judges have to decide issues. They are, in the first place, determined by the pleadings but, as we all know, those issues can change and become more or less important as a trial proceeds. It may be, for instance, that one of the issues is the credibility of a major witness. If the case for one side is dependent upon the judge accepting that witness’s evidence, then you will deal with that as early as possible.

Principle 3

A reader absorbs information better if they can absorb it in pieces. Don’t be afraid to have paragraphs with only one or two sentences.

You will have all noted the change in the way judgments are written. Even the great Sir Owen Dixon committed what is now a cardinal sin of writing sentences and paragraphs which are too long.

Look at the way the High Court, in particular the decisions of the Chief Justice and Keane J are set out. The paragraphs are, generally, short. They use headings and break up their decisions into digestible pieces. You should do the same. Break up larger blocks of text by using headings, shorter paragraphs, and white space. If you are dealing with, for example, a test which has a number of factors then set them out in bullet point form rather than within a paragraph separated only by commas.

Principle 4

A judge will pay more attention if you approach your material from their perspective, not yours. Understand what a judge has to do. Findings of fact have to be made. Upon those findings, issues are determined. Upon those issues, orders are made.

With that in mind, your written submission will set out the issues which need to be determined and the facts which need to be found before that determination can be made.

When you do that you will not be hiding the point you wish to make in the middle of the paragraph. Consistent with the imperative to provide context, you will make your point first and then provide the cogent reasoning to support it.

Remember this, a submission should not be written as if it is a mystery novel. The conclusions should be obvious and made early in the document.

If you want to adopt a template for dealing with issues, then one means of doing it is to:

B

say how the issue should be decided

D

set out the relevant facts

E

apply the law to those facts which demonstrate that the issue should be decided in the way you have already provided

How can you blend the written and the oral so that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts?

The final thing I wanted to say concerns the difficulty some people have with speaking to written submissions. There are few things more deflating than for counsel to hand-up the written submissions and say I have nothing further.

This is meant to be an exercise in persuasion not abandonment. If you do this you are forgoing one of the most effective ways of persuading someone, that is, through discussion and argument.

In any event, as I’ve already said, the written document should, unless otherwise ordered, be an outline.

“Remember this, a submission should not be written as if it is a mystery novel. The conclusions should be obvious and made early in the document.”

So, what can you do to engage with the written document? Take the judge to those parts of it which are at the heart of your case. Don’t read out what is written but have something ready which will allow you to expand upon that which is on the piece of paper.

One area in which this type of interaction can be very helpful is when you are dealing with issues of credit or particular findings of fact. It is much easier to impress upon the judge the value of certain pieces of evidence or parts of certain documents in oral argument. You should not, for instance, place large slabs of transcript into a submission. You should, though, provide the relevant transcript references. That will allow you to ask the judge to take up the transcript and go to the particular page or pages and ask him or her to read the relevant parts. That allows the judge to remember that evidence and to mark it up. It allows you to compare the evidence given by other people in the same way. It allows you to draw the judge’s attention to consistency or inconsistency with exhibits.

This is much more effective being done when you’re standing up than expecting and hoping that the judge will, with the file spread out on the desk, find all these things and absorb what you say are the important aspects.

Similarly, while you will provide the correct references to authorities in your submission, it can be more effective to take the judge to particular parts of an authority, direct attention to them, comment upon them, and then analyse evidence in the light of the principles set out in those authorities.

I will deal briefly with the manner in which you should conclude the preparation of your written submission. When you have finished it, close the document and do something else. If it is possible leave it for a few days and reread it. Edit it, cut out the unnecessary adjectives, adverbs and modifiers and shorten it. You will, because we all do, miss some typos or infelicities of grammar because you will read what you expect to read. One method of doing this kind of editing is to have the submission read back to you by the computer. I find that a particularly unappetising task. Another method, which I have found useful when editing judgments, is to print it out using an entirely different typeface. It is remarkable how that can let you see what you have not seen before.

Finally, do not overlook the editing and correction process. There are few things more infuriating than to find that a reference to transcript or to a particular authority is incorrect and that you are required to then trawl through the transcript or try to find the authority yourself. This does not encourage confidence in the balance of the document.

Semipalatinsk is a large area in the north east of Kazakhstan which, in 1949, was known as the Kazakh SSR, one of the constituent republics of the USSR. On 29 August of that year it was where the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic device[i]. The reaction here and elsewhere was one of surprise and of heightened concern about the USSR’s military capacity and intention. General apprehension about the Cold War and the presence of communist spies increased when, a month later, Mao Zedong proclaimed the creation of the Peoples Republic of China.

Against this backdrop of international tension and the dawn of the nuclear age Australia was grappling with its own internal challenges. Shortly before those two events, Australia had been in the grip of one of its most serious strikes. The coal mines were closed and a Labor government had stepped in and used the army to clear strikers. It was a time when, not only Australia, but also many other western nations perceived a direct and substantial threat from communists and their sympathisers.

For contemporary readers, these events may seem distant. That era was defined by leaders such as Clement Attlee, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom; Harry Truman, the President of the United States; and Robert Menzies, who assumed office as Australia’s Prime Minister for the second time in December 1949. Though these events occurred 70-75 years ago, they offer valuable historical lessons about the balance between security and civil liberties.

Marx House, the headquarters of the Australian Communist Party Central Committee on George Street, Sydney, circa 1950. (Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

When Mr Menzies came into office, one of his new government’s highest priorities was the destruction of Australian communism. This was to be achieved through the Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950. The Act outlawed and dissolved the Communist Party of Australia and provided for the confiscation of its assets. Organisations affiliated with or controlled by the CPA could be declared unlawful, and individuals who were or had after 10 May 1948 been members of the CPA could be declared to be so and thus debarred from employment in the Commonwealth Public Service or from holding office in a trade union. A person who was the subject of such a declaration had the onus of proving that he or she was not liable to the making of that declaration.

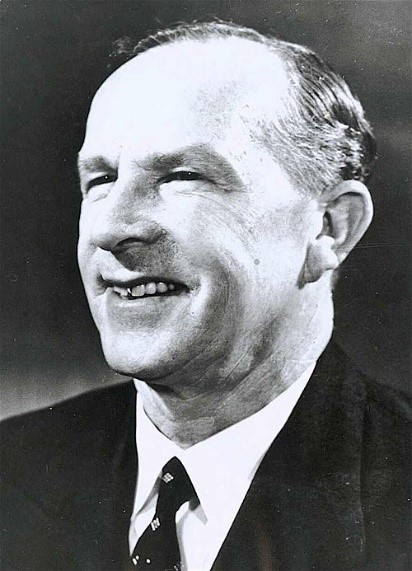

Mr Menzies

This was part of the “war on communism”. It was a conflict about which the participants felt so strongly that they were prepared to cut away at longstanding provisions essential to the healthy survival of the rule of law. Of course we now understand that the Communist Party of Australia, while aligned with the Soviet Union, posed a threat that was not as overwhelming as many then believed. However, it is crucial to understand the prevailing climate of fear and suspicion that shaped the political landscape at the time. That is the precious gift of hindsight. This process was well captured in the words of William Brennan, former Justice of the United States Supreme Court, who said in 1987:

“There is considerably less to be proud about, and a good deal to be embarrassed about, when one reflects on the shabby treatment civil liberties have received in the United States during times of war and perceived threats to national security… After each perceived security crisis ended, the United States has remorsefully realised that the abrogation of civil liberties was unnecessary. But it has proven unable to prevent itself from repeating the error when the next crisis came along.”[ii]

That statement can be neatly contrasted with what was said by Mr Menzies in the House of Representatives after the High Court had ruled that his government’s Communist Party Dissolution Act was unconstitutional. He told the House:

“We cannot deal with such a conspiracy urgently and effectively if we are first bound to establish by strict technical means what an association or an individual is actually doing. Wars against enemies … cannot be waged by a series of normal judicial processes.”[iii]

The decision of the High Court[iv] invalidating the Communist Party Dissolution Act has been described as “undoubtedly one of the High Court’s most important decisions”[v]. Had the Act been upheld and then enforced without scrupulous oversight, then its effect on the rule of law could have been devastating. Former member of the High Court, Michael Kirby, has suggested that apartheid South Africa provided a model of what Australia might have become had the legislation been upheld.[vi]

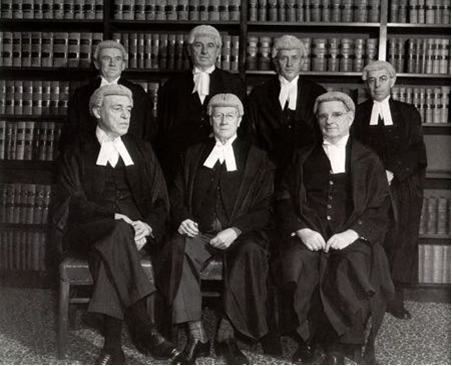

The High Court of AustraliaBack Row: Fullagar, Webb, Williams, and Kitto JJFront Row: Dixon J, Latham CJ, McTiernan J

The ultimate foundation for the decision was the rule of law. It was an example of the constitutional principle that a parliament cannot recite itself into power and, at a more particular level, that only the judicial power is permitted to bridge the gap between making a classification and placing a person within it.[vii]

The Court did not establish a blanket prohibition against reversing the burden of proof, as courts still retain authority to determine whether constitutional facts exist in such cases. Furthermore, the Court acknowledged that while the Commonwealth could not enact such legislation, State governments probably could.

So, who were the principal counsel in the Communist Party case?

Frederick (Fred) Paterson, a Rhodes Scholar, was counsel for the Communist Party. He was the only representative of the Australian Communist Party to be elected to an Australian parliament. He was the member for the State seat of Bowen from 1944-1950.

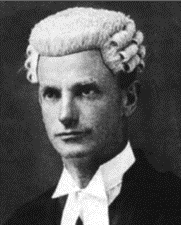

Garfield Barwick KC, was leading counsel for the Commonwealth, who later became the Commonwealth Attorney-General, Minister for External Affairs and Australia’s longest serving Chief Justice, led three silks and six juniors at the hearing.

H V (Bert) Evatt KC was counsel for the Waterside Workers Federation and would become the Leader of the Opposition in the Commonwealth Parliament three months after the High Court delivered its decision.

F W Paterson, Counsel for the Communist Party

G E Barwick KC, Leading counsel for the Commonwealth

H V Evatt KC, for the Waterside Workers Federation

This case illustrates the proposition that in a settled western democracy, the role of the advocate in the protection and maintenance of the rule of law is essential. While the courts, and depending upon their public persona, some judges, can fleetingly become the objects of veneration for their role in upholding that principle, none of this could occur without advocates willing to develop a case and present it to the court. As Sir Gerard Brennan observed:[viii]

“… the courts are the long-stop. The law which rules is the law according to the rulings of the courts, but it is applied in the offices and chambers of the legal profession. It is applied in drafting and advising; in consultations more than in litigation. But, because the courts are the long-stop and because the rulings of the courts determine the way in which the law operates, judicial decision-making is critical to the maintenance of the rule of law. So it is in litigation that the practising legal profession works at the cutting edge of the rule of law.”

In a settled democracy, where the practice of law can result in a comfortable living, it is sometimes too easy to become more concerned about the prompt payment of fees than the integrity of the institution which allows the fee to be charged. While the courts do resolve the issues and while members of the judiciary do decide the cases which allow the rule of law to be maintained, they do not reach out into the community to bring the cases before them. Without the profession acting for those whose rights have been affected and without its members recognising that sometimes there are aspects of legislation which are inconsistent with the rule of law, then damage can be done.

It is obvious that our society is subject to numerous threats: by terrorists, by organised crime and by the galaxies of unlawful activities which revolve around the sale and consumption of illicit drugs. Evolving criminal methodologies and terrorist tactics demand innovative approaches and a resolute determination to deal with them.

It remains a necessary part of an advocate’s role when engaged in litigation to identify elements of legislation that, despite worthy intentions, may diminish the rule of law. This obligation can be complex. Whether in jurisdictions with human rights legislation or without, advocates serve the rule of law by applying validly enacted laws and interpreting them appropriately. The common law has always sought a balance between individual freedoms and community protections. If legislatures restrict fundamental freedoms or diminish common law values, advocates must be prepared to present arguments challenging these actions.

As Sir Gerard Brennan concluded:

“Sometimes that may be an anxious duty, sometimes difficult to perform. But that has long been the experience of a robust and proud profession.”[ix]

[i] In 2007, the capital of this area, Semipalatinsk City, changed its name to Semey because its existing name had negative associations due to the extensive atomic testing which had taken place.

[ii] ‘The quest to develop a jurisprudence of civil liberties in times of security crises’ (1988) 18(11) Israel Yearbook on Human Rights 1.

[iii] 212 Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 13 March 1951, 366.

[iv] Australian Communist Party v The Commonwealth (1951) 83 CLR 1 (Dixon, McTiernan, Williams, Webb, Fullagar and Kitto JJ agreeing; Latham CJ in dissent).

[v] George Winterton, ‘The Significance of the Communist Party Case’(1992) 18 Melbourne University Law Review 630.

[vi] ‘H V Evatt, The Anti Communist Referendum and Liberty in Australia’ (1991) 7 Australian Bar Review 93, 100-101.

[vii] Geoffrey Sawer, ‘Defence Power of the Commonwealth in Time of Peace’ (1953) 6 Res Judicatae 214, 219.

[viii] ‘The Role of the Legal Profession in the Rule of Law’ in Francis Neate (ed), Rule of Law: Perspectives from Around the Globe (LexisNexis, 2009).

[ix] Ibid.

This is a story about conflict.

About conflict between the parliament and the judiciary.

About conflict between reformers and conservatives.

About conflict between strong-willed men.

But before I go to that conflict, let me orient you in time.

It is a century ago. It is 1922 – an extraordinary year. The world was moving out of the grim shadow of the Great War and into the roaring 20s. The depression was still years away.

George V was King-Emperor. Billy Hughes was Prime Minister.

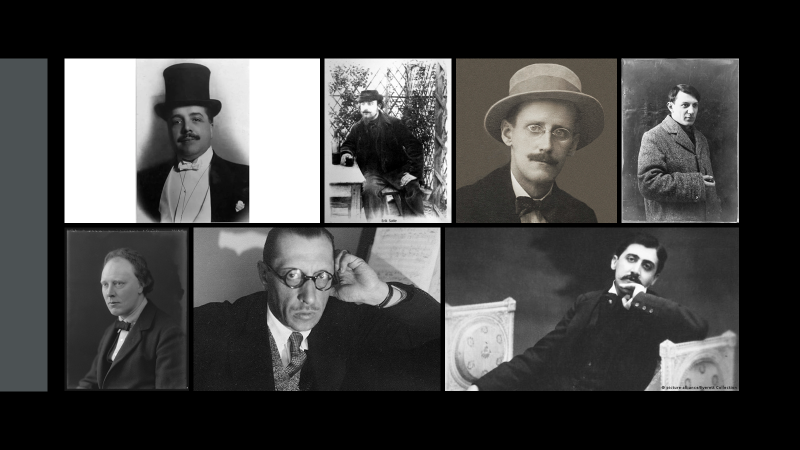

Remarkable things were happening. Insulin was successfully used for the treatment of diabetes. James Joyce’s Ulysses was published. The other end of the literary scale saw the first issue of the Reader’s Digest.

Howard Carter found the entrance to Tutankhamen’s tomb. TS Eliot published The Waste Land.

And in what was a most remarkable gathering, Sergei Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky, Pablo Picasso, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Erik Satie and Clive Bell dined together at the Majestic Hotel in Paris. The first and only time that Proust met Joyce. What a dinner. And what must the bill have been.

Elsewhere things were not so friendly. The Irish Civil War commenced which led, after some five months, to the creation of the Irish Free State. Mussolini marched on Rome and the fascist dictatorship commenced. Germany was experiencing the hyperinflation which contributed to the collapse of the Weimar Republic.

Vegemite was invented and Doris Day was born.

And in more prosaic news, the Ottoman Empire collapsed and the USSR was formed.

In Australia the Spanish flu had burnt out a couple of years earlier but there were still deaths from the plague in Sydney, Townsville and Ipswich.

And what of Queensland? A little backwater barely emerged from a colonial past?

No, this State had one of the most radical governments, by Australian standards, of the time. A Labor government in a State which had had the first Labor government in the world – Anderson Dawson’s short-lived Premiership.

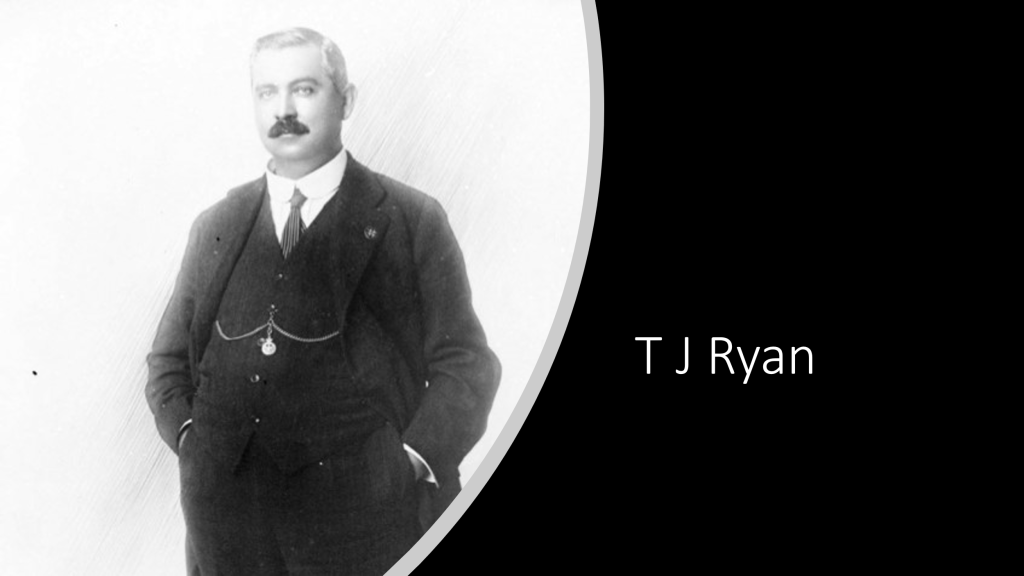

The first majority Labor government was led by T J Ryan to victory in 1915. It set about making big changes to labour law and introduced workers compensation. The State purchased properties, it opened State run retail butchers’ shops which sold meat cheaper than elsewhere. Railway refreshment rooms were taken over, state hotels were built or purchased, a producing agency was established, coal mines were acquired, iron and steel works were opened, and a state insurance department was established.

It also legislated massive constitutional change. Ryan introduced a bill to abolish the upper house in 1915 and, after considerable confrontation, the Legislative Council ceased to exist on 23 March 1922.

A lot happened in March of 1922.

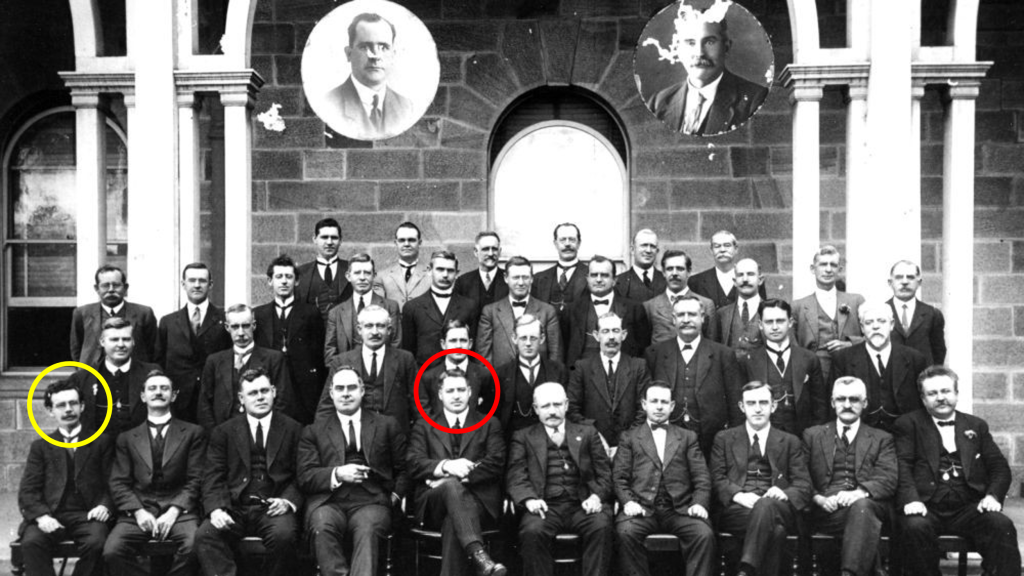

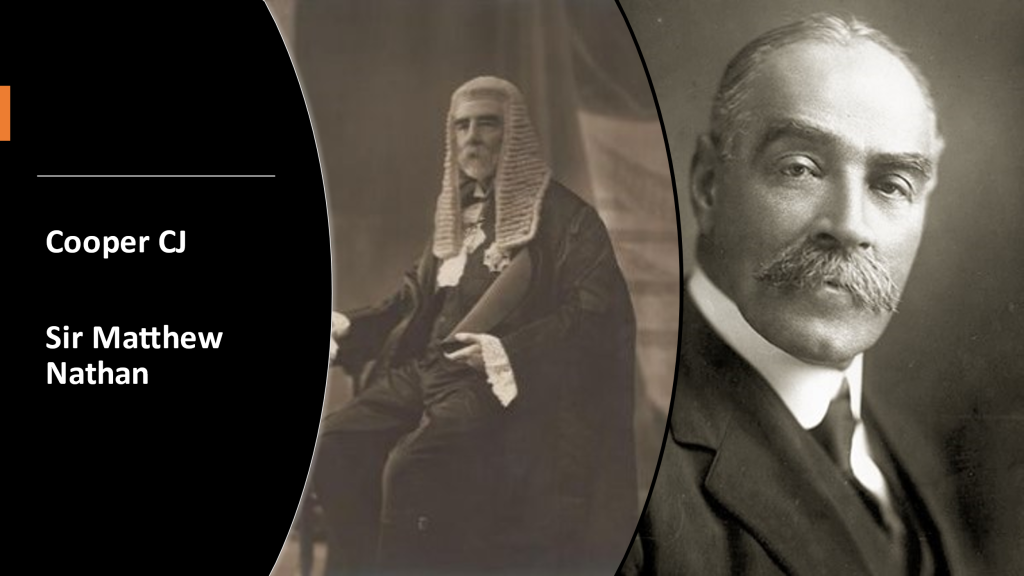

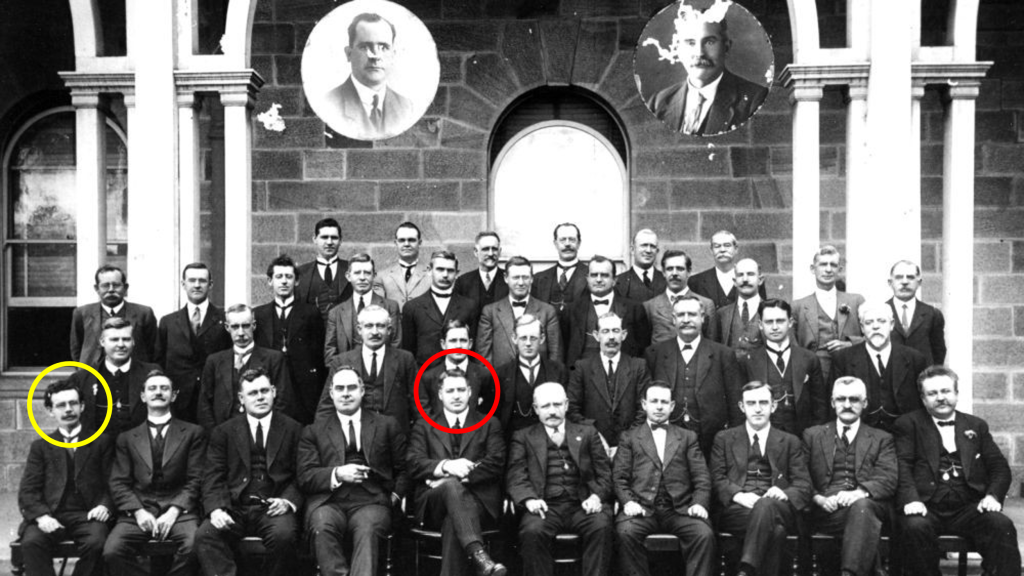

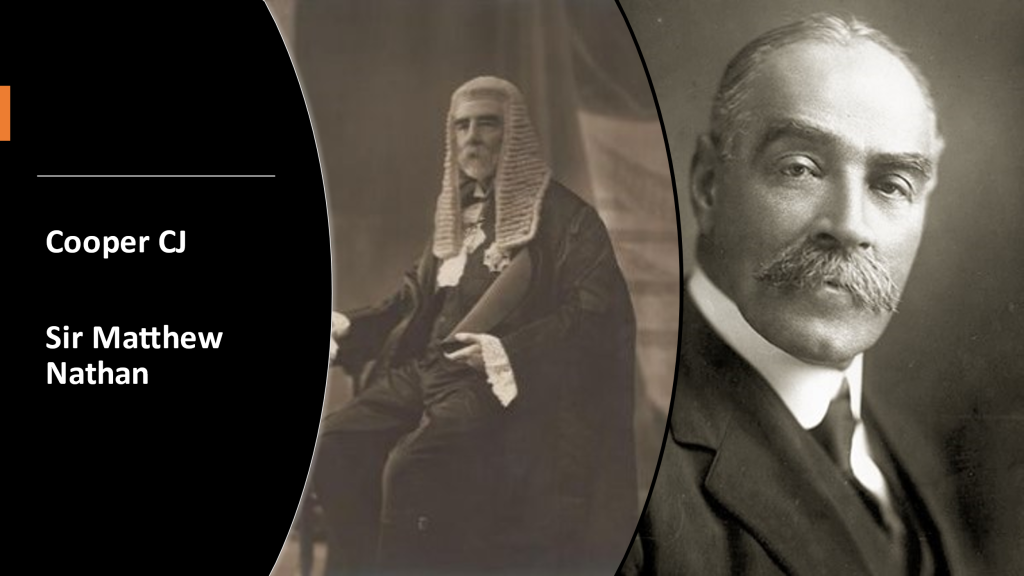

At the end of that month, three judges of the Supreme Court, all the judges sitting in Brisbane including the Chief Justice, were forced into retirement because each of them was over 70 years old – Pope Cooper, Patrick Real and Charles Chubb.

It was Labor policy to introduce retirement ages for State judges. From the time judges were first appointed in the colony they had, subject to good behaviour, been appointed for life. They could only be removed by an address by both houses of parliament. Or so they thought. That had been the case throughout the British influenced jurisdictions since the Act of Settlement in 1701.

From 1915 until the end of 1919, Thomas Joseph Ryan was the Premier and Attorney-General of Queensland. He would appear in the Supreme Court as Attorney-General and it may be that his view of the court was influenced, to some extent, by his disagreements with some of the members of that court. I’ll come back to that. Ryan resigned as Premier after a resolution of a special federal Labor conference asked him to enter federal politics. He did that. He resigned in 1919 and was elected to the House of Representatives in the same year. He showed all the signs of commencing a successful and influential career in federal politics. But that ended abruptly when he died of pneumonia in Barcaldine in 1921.

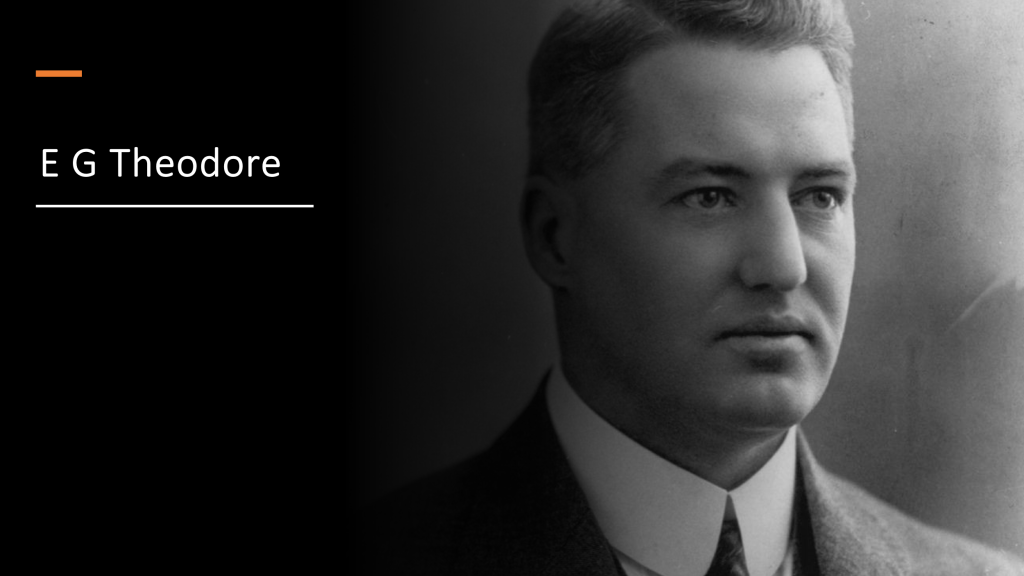

Ted Theodore had been Deputy Premier and Treasurer and he took Ryan’s place as Premier. He continued along the way established by Ryan and his pursuit of interventionist economic policies led to allegations that he was wanting to set up a socialist state. Thus, the nickname “Red Ted”. Like Ryan, he later left State politics for the federal arena and became deputy leader of the federal Labor Party and Treasurer under James Scullin.

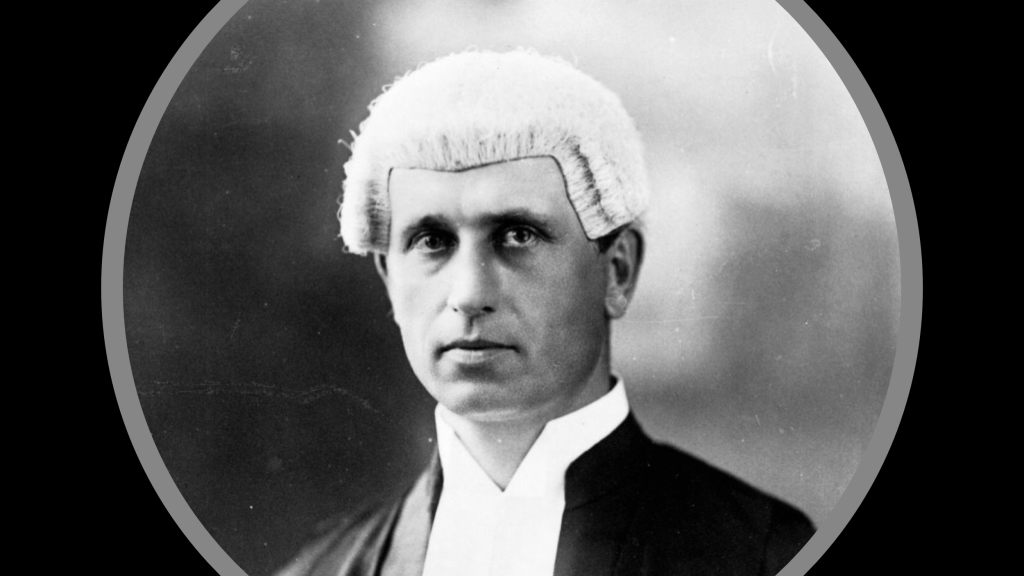

The next man in this story is Pope Alexander Cooper. He was born in New South Wales and attended the University of Sydney at the same time as Edmund Barton and Samuel Griffith. He went to London and practised at the bar for a few years before returning to Australia in 1874. Cooper was appointed Attorney-General and won the seat of Bowen. It was an unhappy time for him and he was pleased to resign and accept appointment as the Northern Judge based in Bowen. He became well-known for his dissatisfaction with the money allowed to him for the cost of circuits. He argued with his friend from university, who was now the Premier, Mr Griffith QC, over the cost he incurred.

Things came to a head in 1887 when he was conducting a circuit in Townsville. There were eight capital cases and six others which carried a possible penalty of life imprisonment to be heard. The government had told him that his circuit expenses for that year were not to exceed £400. He had already incurred expenditure of £286. He let the relevant department know that, as soon as the amount of his travelling expenses reached a point at which the balance of £114 threatened to become exhausted, he would close the court and discharge the prisoners. And he required an assurance that his expenses would be honoured. Soon after that, he read that correspondence in open court and told the prosecutor that he intended to discharge the prisoners. An adjournment was sought by the prosecutor and a few hours later a suitably worded telegram arrived which satisfied him and the circuit continued.

Cooper was a difficult man. He threatened to jail a journalist for contempt and when the apology from that man was insufficient, he sentenced him to 12 months imprisonment. Later, it appeared that Cooper recommended that he be released and he was, in fact, released within six weeks. But that sentence was often raised against him as a subject of complaint about his conduct.

There is no doubt that he was an irascible man. He was a pedant. He did not get on well with his fellow judges. When he was appointed Chief Justice, Patrick Real was so upset that he threatened the stability of the court. In order to assuage him, Real was appointed Senior Puisne Judge. His remarks made at the ceremony to welcome Cooper as Chief Justice bear repeating. Or, at least, some of them. He said: “I believe that my conduct during the years I have been on the Bench has always been such as to make you esteem and love me, as yours has made me esteem and regard you. I can say that but for the circumstance I have referred to I could not have sat on this Bench other than under a feeling of absolute insult.” The circumstance is his appointment as Senior Puisne Judge. He went on in those terms for quite some time.

During many of the years that Cooper was on the bench, it was the practice of the Court that the presiding judge could call on any robed counsel sitting at the Bar table to defend an unrepresented prisoner – a dock brief. James Blair (later to be appointed to the court and then become Chief Justice) was in that position one day when Cooper required him to defend an unrepresented prisoner charged with wilful murder. Blair asked if he might have the assistance of Bart Fahey who was also at the table. Cooper allowed that. Blair then asked for an adjournment of the trial because, among other things, neither counsel knew anything about the case. Cooper ordered that they be provided with a copy of the depositions – then he adjourned the trial for one hour. You can see why people thought that he was a difficult man.

Cooper did have some redeeming features. He took an action all the way to the High Court in an effort to exclude judges from having to pay income tax. An admirable but doomed experiment.

Patrick Real was born in Ireland. He came to Queensland and attended school until he was 12 years old when he had to go to work to support his family. He was a carpenter for some time and worked in the railway shop at Ipswich. Notwithstanding his lack of formal education, he qualified for the profession and became a successful barrister. On the bench, he was liable to express opinions on a wide variety of matters, he was not reluctant in threatening counsel with committal for contempt and recognised, himself, that he could be a little abrupt. He was, though, a respected and well-liked member of the court.

Charles Chubb was another with Ipswich connections. He was born in London, completed his schooling there and then emigrated to Queensland with his family. He was appointed to the court in Townsville in 1899 and transferred to Brisbane in 1908. He sat on many important cases including the sensational murder trial of Patrick Kenniff and the appeal from a decision of Chief Justice Lilley which led to Lilley’s resignation. He was akso given to musing while on the bench. There was this exchange with Charles Jameson:

In an affidavit read before the Supreme Court in Townsville, it was stated that a certain person was a strict teetotaller.

Mr. Justice Chubb said: “I very much admire him. I wish I were a teetotaller too. I would rather be a teetotaller than a publican, of the two. Of course I speak generally.”

Mr. Jameson: “Well, I think, your honour, I should prefer to be a wealthy publican than a poor teetotaller.”

His Honour (laughing): “But, then, you have no conscience, Mr. Jameson.”

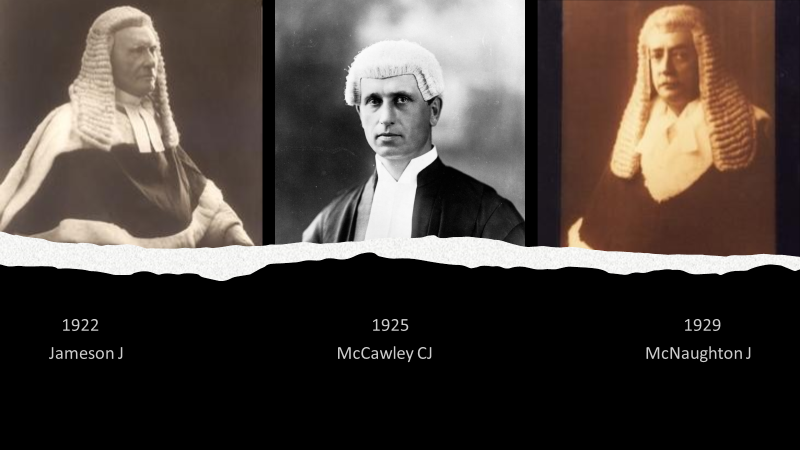

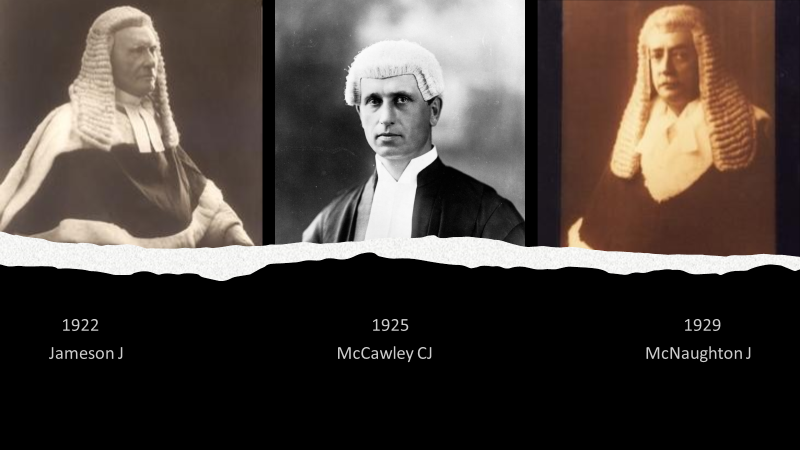

Charles Jameson was later appointed to the Supreme Court.

There was an apprehension, an apprehension reasonably held by the government, that the Court was conservative and actively opposed its political agenda through some of the decisions it gave.

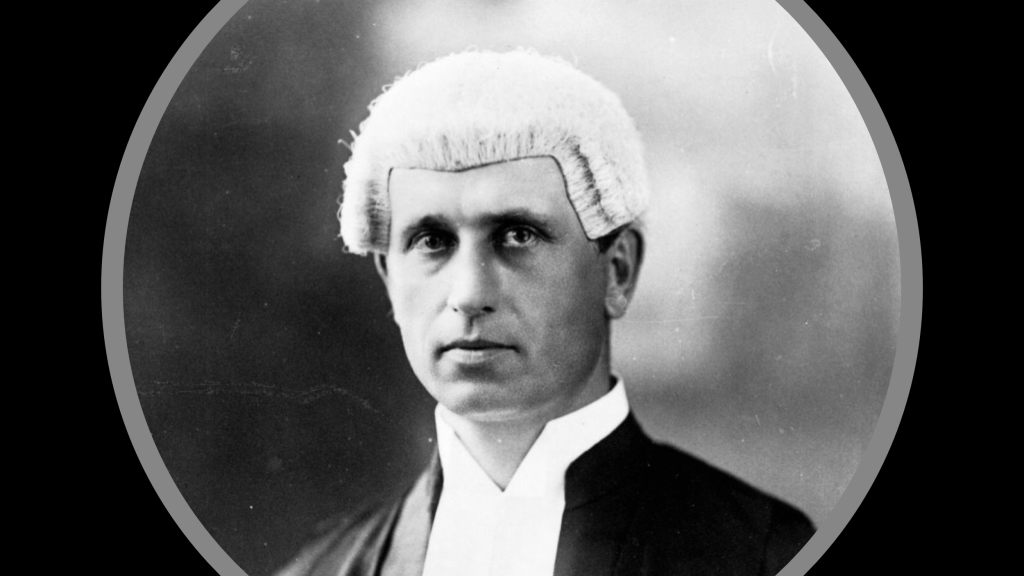

One of the flashpoints occurred with the appointment of Thomas McCawley as President of the Court of Industrial Arbitration. It was an appointment which carried a seven-year term. Soon after that he was appointed a judge of the Supreme Court. The then Constitution provided that judges of the Court should hold office for life during good behaviour. Among the many questions which were raised was whether the seven-year appointment on the industrial court conflicted with the provisions of the Constitution. Much has been written about this appointment. McCawley’s place on the Supreme Court was opposed by the Bar and the Full Court accepted the objection on the basis that the industrial legislation was not effective to impliedly repeal the relevant part of the Constitution. The High Court agreed with that but, when that was taken further, the Privy Council overruled the High Court and held that the Constitution was able to be amended simply by passing inconsistent legislation.

The opposition to McCawley had been bitter. And it was expressed in substance and in petty actions by Cooper. When McCawley came to present his commission as a judge of the Supreme Court, he followed the other judges into the courtroom and stood behind them. There were only enough seats for the sitting judges. After those judges were seated, McCawley attracted Cooper’s attention, presented his commission and asked to be sworn in. Before that could happen, counsel – Arthur Feez KC – moved to oppose the swearing in and argument began. No judge paid any further attention to McCawley until he interrupted and said to Cooper: “Are you going to leave me standing here all day?” Only then did Cooper order a court official to bring a chair.

McCawley was appointed in 1917. In the 1918 State election, the Labor Party made it clear that it desired to reform the Supreme Court and, after its victory, that was reinforced in the Governor’s opening speech of the new session of Parliament. At that time, there was no provision for parole or anything like that. Prison terms could be remitted and that was generally done after consultation by the Attorney-General with the sentencing judge. By 1920 the government took the view that the judges were refusing to cooperate in moves to reduce severe prison terms and so abandoned all consultation and remitted sentences without cooperation. Other areas of conflict included substantial disagreements between the government and pastoralists who fought for the right to engage labour as they saw fit. These views clashed with those of the government and the Premier formed the view that the Court was on the side of the pastoralists among others.

Cooper had been reported, in 1915, as publicly criticising the Ryan Ministry on the grounds of its socialism. He made no secret of his views on conscription – which were opposed to those of the Ryan government. And, in 1918, he was quoted in the Brisbane Courier as issuing a warning to the community against the prospect of the Labor government interfering with judicial independence by making political appointments and that the McCawley appointment was merely preparatory to an attack on the Supreme Court.

Ryan didn’t hold Cooper in high regard. He said, in Parliament, that Cooper’s decisions in two particular cases had shown “want of integrity rather than an imperfect knowledge of the law”.

Nevertheless, Premier Ryan hoped that the judges over 70 would retire and his legislation would not need to be brought into force. And so, he did not advance the proposed legislation – he hoped that the judges might blink and that the crisis would be resolved. But they didn’t blink.

When Theodore became Premier, he introduced the Judges Retirement Bill. It imposed retirement on all judges who had attained the age of 70 years and required that all future judges retire at the age of 70. The present judges would still be entitled to pensions but those who attained the retiring age in the future would not receive pensions.

There were two other parts to the proposal – the District Courts were to be abolished and the judges of those courts were to be appointed to the Supreme Court.

The opposition was vehement in its rejection of the Bill. They said it was a sheer act of victimisation. The government did not suggest that grounds existed for the removal of any of the judges, no doubt because that would have required proceeding by way of a Parliamentary address for removal which would have required proof of misconduct or incapacity. The device of age disqualification was engaged.

The Bill came on for debate in late 1921. As part of the effort to reduce the conflict, Premier Theodore said that the bill would not be proclaimed until March 1922. The speeches in the house went on for days. There were mishaps along the way. At one point there were insufficient government members in the house and an opposition amendment was passed which would have had the retirement age only apply to new appointments. After a frantic search for the missing members, the bill was recommitted and the amendment revoked.

One of the saddest parts of the process occurred when Real, having sought and obtained permission to do so, appeared before the Bar of the Legislative Assembly. He made a lengthy speech, apparently in an attempt to demonstrate that he was still fit and capable. He ranged across many subjects and began by pointing out that he had found in the government’s favour the McCawley case. He said that the bill, if enacted, would work a significant financial detriment on him. He claimed that he had sacrificed £100,000 to sit on the bench. A young barrister, Eddie Stanley – who went on to become a member of the Supreme Court – was there. He recalls it this way:

“I managed to get into the House and heard his speech. The place was crowded with members and others. For several minutes his speech was masterly, and one could feel that his star was in the ascendant. Then age and emotion overcame him; his address became halting and confused. One could feel that everyone was most sympathetic for him: but people came away saying – “how tragic!” and feeling that the legislation was justified.”

The Attorney-General, John Mullan, who was not a lawyer, was aggressive in his speech when he opened the second reading debate. He said: “I will allow no man in this House to insult me by interjections. If he does, he will get it in the teeth every time.”

Mullan argued that there were two policy justifications for the change. First, he said that, with the abolition of the District Courts, the judges would be required to do more circuit work and that men over the age of 70 could not cope with the physical demands of travelling. The second, and more credible, reason was that advanced age might dull a person’s mental acuity. And that having an upper limit recognised that.

Three grounds were advanced by the Opposition. The first was related to the independence of the judiciary but was founded in an obscure argument which had been rejected by the Privy Council. The second focused on judicial independence in the narrower sense. One of the opposition members put it this way: “I say it is because the Government want a more weak and pusillanimous judiciary which they can control.” Finally, it was argued that the legislation amounted to a repudiation of the state’s contractual arrangements with the current judges.

When Theodore addressed the House, he argued that the provision for pensions in the 1867 legislation demonstrated that the legislature had anticipated that judges would retire of their own volition because their advancing age would compromise their abilities. He could not help, though, making some remarks clearly directed to the three judges over 70. He said: “Great delicacy is needed in touching upon these matters, because no one wants to reflect on the individual judges who come under the Bill, but it is somewhat unfortunate that some of them have not seen fit to retire.”

The legislation was passed along party lines in the Legislative Assembly.

The Bill reached the Legislative Council seven days later and it passed on 18 October 1921. Six days later the Legislative Council Abolition Bill was introduced into the Legislative Assembly. That later passed in the Council with the help of the so-called “Suicide Squad” of Labor Party members who were appointed on the understanding that they would vote that house out of existence.

Further efforts were made to prevent the Bill coming into effect. Cooper called on the Governor, Sir Matthew Nathan, and expressed his opposition to the bill. The judges asked the Governor to refer the matter to the King but, after taking advice, he declined to do that.

The three judges who were forced off the court were farewelled at a sitting on 31 March 1922. Cooper (who was 75) had been on the court for 40 years, Real (who was 74) for 32 and Chubb (who was 76) for 33. Arthur Feez KC – who had appeared to argue against McCawley’s appointment – remarked that it was a unique occasion because never in the whole course of judicial life in the British speaking community had such an episode as was happening there taken place. (Feez was right about the farewell being unique, but there had been similar legislation passed in New South Wales in 1918. It, though, did not result in the immediate retirement of any Supreme Court judges.)

On the following day, Attorney-General Mullan announced the new appointments. McCawley, who had not attended the farewell, was to become Chief Justice and the District Court judges were appointed to the Supreme Court.

Real attempted to practise as a consulting barrister but with little success. He died in 1928. Two years later, Chubb passed away. Cooper, who may have been the principal target, died in August 1923, less than 18 months after his forced retirement.

What change did it make to the court?

Jameson turned 70 in December 1922. McNaughton retired in 1929.

Thomas McCawley was Chief Justice for only three years. He died, in 1925, from a heart attack. He was running along the platform at Roma Street Station to catch a train for the circuit sitting at Ipswich.

As for Theodore, he entered federal politics and became Treasurer under Prime Minister Scullin. But he was then caught up in the Mungana Scandal, eventually lost his seat and left politics at the age of 47. And then he, the so-called socialist, “Red Ted” Theodore, went into business with Frank Packer and became the chairman of directors of Consolidated Press – but that is a story for another day.

Marx House, the headquarters of the Australian Communist Party Central Committee on George Street, Sydney, circa 1950. (Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Marx House, the headquarters of the Australian Communist Party Central Committee on George Street, Sydney, circa 1950. (Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Mr Menzies

Mr Menzies

The High Court of AustraliaBack Row: Fullagar, Webb, Williams, and Kitto JJFront Row: Dixon J, Latham CJ, McTiernan J

The High Court of AustraliaBack Row: Fullagar, Webb, Williams, and Kitto JJFront Row: Dixon J, Latham CJ, McTiernan J

F W Paterson, Counsel for the Communist Party

F W Paterson, Counsel for the Communist Party

G E Barwick KC, Leading counsel for the Commonwealth

G E Barwick KC, Leading counsel for the Commonwealth

H V Evatt KC, for the Waterside Workers Federation

H V Evatt KC, for the Waterside Workers Federation