Author: Jeff Fitzgerald

Publisher: The Federation Press

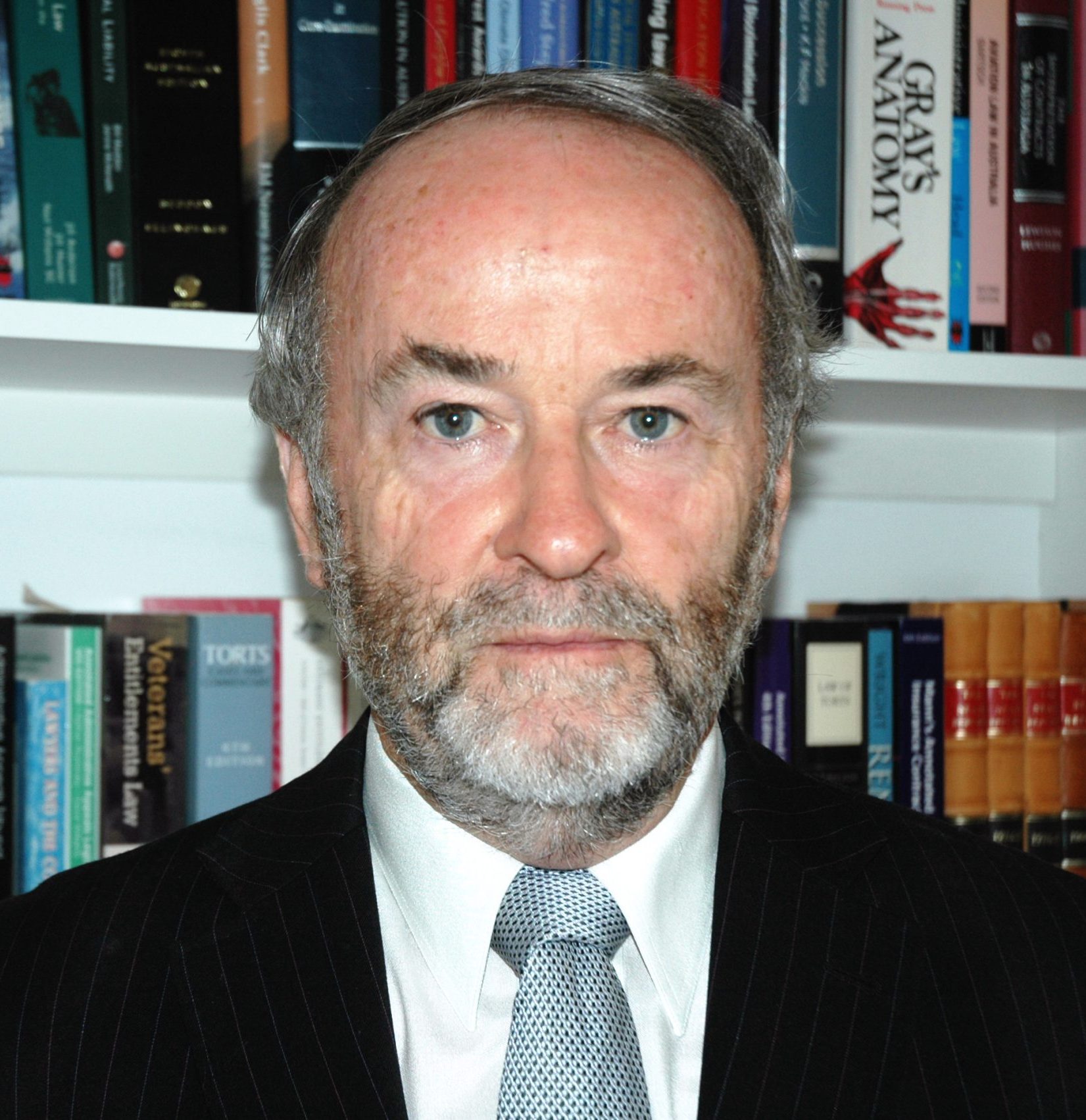

Reviewer: Brian Morgan

Hard Cover 505 pages.

What an honour I have been given to review this book. What an insight it provides to one of our greatest lawyers of the last fifty years. The author’s note at its commencement is, in itself, revealing as it paints a picture of what Sir Gerard wanted and didn’t want, including his reluctance to have a biography written about him and a desire that his personal life remain private.

Fortunately for the reader, it soon became evident that the book could not be written without referring to Sir Gerard’s family and understanding his relationship with them. In particular, his wife, Pat, like so many lawyers’ wives, basically, ran the family during the frequent and prolonged absences of her husband caused, inter alia, by the requirement that he spend substantial periods of time away from Queensland, where his home was at that time. But as is evident from the book, Pat’s contribution to Sir Gerard and their family went far beyond that. Pat was truly Sir Gerard’s partner in life. They became, if anything, closer, as Pat’s health deteriorated leading to Sir Gerard assuming many of the domestic tasks that she had previously done.

I want to digress from the text for a moment and make a plea to all young people who are at the Bar or considering life at the Bar to read this book as a means of opening their eyes to what a barrister’s life really entails. I well remember interviewing prospective candidates to be my reader. On one occasion, a young man entered my Chambers and handed me a list of his requirements, which included working hours of 9.30am until no later than 5.30, no night work, no weekend work, six weeks vacation, each year, and an income well beyond that which a young barrister might expect to earn during his training. I stood up and offered him my seat explaining that terms such as this suggested he should be the master and I the underling. He never completed his training for the bar and, as far as I can determine, never entered practice. And, did I mention that he demanded one afternoon off per week to play sport?

The book being reviewed shines a light on the only way, of which I am aware, to succeed at the bar, namely, to work long hours, be prepared to be overworked, be respectful to the Courts and your colleagues and fully prepare your work.

I did not know that Sir Gerard’s father had been a Supreme Court Justice in Queensland. Nor did I know that Sir Gerard was, initially, refused Admission to the Bar by the Chief Justice due to a technicality on which no one wished to rely, except the Chief Justice. Another counsel at the bar table removed his wig and spoke loudly enough to be heard, suggesting that Sir Gerard was being punished for the “sins of the father” who had not been overly popular with the bar or, for that matter, with some of the Judges in Queensland. The decision to refuse his admission was quickly reversed due to the intervention of one of the other judges sitting on the Admissions Applications.

Sir Gerard was a highly intelligent and a lateral thinker and, as one sees many times throughout the book, he had the uncanny ability to re-consider older and long accepted cases, to dismantle them into fundamentals and replace them with a conclusion that has since stood the test of time.

But, although the book purports to focus on Sir Gerard, it presents far more than that. The relationship between Sir Gerard and various High Court justices over the years matured to permit genuine friendships to develop even while frequent deep disagreements concerning legal principles arose in their judicial work. It is to the credit of each person involved that such differences on principle did not interfere with the mutual respect of the justices for each other.

Sir Gerard was, whether on the Bench or in his private life, a down to earth person. He valued his family, his Church (he was a Catholic), First Nations people, the practice of the law and the importance of getting things right.

He found time to be a volunteer for the St. Vincent de Paul Society and, with his wife, would distribute fruit and vegetables to the needy on a Sunday night, introducing himself as “Gerry from St. Vincent de Paul”. It may have been a sign of the times that eyebrows were raised when Sir Gerard was observed sitting talking to First Nations people. The reality of Sir Gerard Brennan, however, was that he treated all people equally.

I particularly enjoyed the short outlines of the personalities of other justices who sat with Brennan as I knew some of them sufficiently well to have one pull up at a red light in a car bearing an L plate, one Sunday morning and, from the passenger seat, give me a very obvious greeting and another who told me that they could always tell when pleadings had been settled by me, from the first page, as they were too voluminous! I also managed to have a heated but not unfriendly discussion on a legal topic with Michael Kirby during a legal convention in Adelaide in the mid 70’s.

Sir Gerard emerges from the pages of the book as remaining a humble man, to his final days.

This book makes for riveting reading by anyone, lawyer or otherwise, who seeks to better understand the workings of the High Court of Australia.

I will conclude this review by quoting the comment of another great Queensland lawyer, now former Chief Justice of the High Court, Susan Kiefel, who said that Brennan regarded:

“The absence of unjustified discrimination, the peaceful possession of one’s property, the benefit of natural justice, and immunity from retrospective and unreasonable operation of laws” as of critical importance … he saw them as values which served to explicate and illuminate the common law, tempered by the need for the law to develop incrementally and in accordance with precedent, the judicial method and the separation of powers. Unprincipled judicial discretion was anathema to him. What was necessary was consistency and predictability”. [2022] HCATrans 135, cited at page 483 of the text.