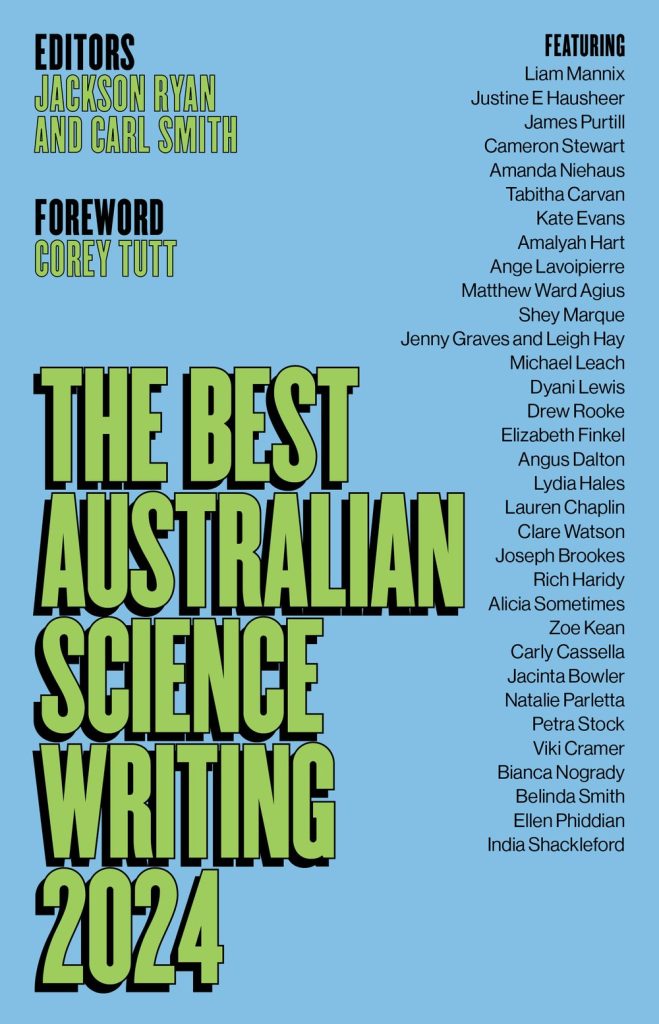

Editors: Jackson Ryan and Carl Smith

Publisher: NewSouth Books

Reviewer: Stephen Keim

An anthology of recent articles on science should almost be a compulsory activity, to be undergone every six months or so. From a young age, I thought that science was an unadulterated good, the pathway to a better life for all human kind. I was always a sucker for the Whig view of history. I now know that science is like everything else that promises and provides power, capable of being misused, corrupted and of bringing death and destruction upon the world.

I still think we should read science writing on a regular basis. I am not as sure about my arguments to support that proposition but, maybe, The Best Australian Science Writing 2024 (“BASW24”) provides some clues.

Scientists tend to do interesting things. Sometimes, they do make discoveries and achieve things that make other people’s lives better. While it is true that a person could know all the science there is to know and know nothing about the world, the scientific view of reality is one way of seeking understanding, albeit, that such understanding is incomplete on its own. If art and literature provide other pathways to understanding, it is heartening that BASW24’s collection includes Poetic Constellations – An Exploded-Sonnet Sequence (which is indeed a series of related poems) by Shey Marque and Origins – of the Universe, of Life, of Species, of Humanity, a libretto for a short opera by Jenny Graves and Leigh Hay. There are several other contributions in BASW24 which establish that great science writing need not only take the form of prose.

Apart from the Foreword by Corey Tutt OAM and an introduction by the editors, Ryan and Smith, BASW24 contains 33 contributions, the whole thing packed into 293 pages. There is room to touch upon a plethora of areas of science endeavour and the editors have delivered.

One of the loveliest pieces is Liam Mannix’s essay about Sarah Lloyd, a woman who has established, near Devonport in northern Tasmania, Australia’s largest collection of slime moulds outside a research institute. The essay expands its focus and introduces the reader to the world of slime moulds and their remarkable abilities. Slime moulds may not have discernible organs much less a brain but can nonetheless make rational life decisions and solve puzzle mazes as a means of obtaining optimum access to food resources.

Falling into the “I really needed to know that” category is Elizabeth Finkel’s This Little Theory Went to Market which analyses all the evidence and speculation about whether the Covid pandemic was the result of a virus leaking from the laboratories of the Wuhan Institute of Virology or whether the virus transferred itself to humans from a dead wild animal on sale at the Huanan Seafood Market, in the city of Wuhan, itself.

While Finkel’s verdict is that the evidence favours the Seafood Market as the most likely source, the most interesting conclusion was not scientific but political and economic. Finkel reveals that, despite the slanderous impact of the laboratory leak theory on China and its scientific institutions, local politicians were not displeased when that theory was born. This paradoxical attitude is because the food trade in locally captured wildlife is very profitable to the city of Wuhan and locals preferred the laboratory to be blamed rather than the thriving wild food trade be diminished.

A number of heart warming stories in BASW24 involve important advances in health science. The Heroes of Zero by Cameron Stewart maps the amazing progress achieved by the Children’s Cancer Institute in Kensington, Sydney over forty years in finding cures for an increasing number of the remaining cancers which cause the deaths of children. As well as portraying the work of the institute, the Heroes of Zero (zero deaths is the avowed aim of the Institute’s work), provides charming introductions to executive director, Michelle Haber, and a number of other people who have contributed to the Institute’s work and continuing success.

Angus Dalton’s How Scientists Solved the 80-Year-Old Mystery of a Flesh Eating Ulcer is the story of a small group of scientists attacking a very difficult problem and facing down scepticism all the way through to solving the mystery. The Buruli ulcer has been a painful scourge present in parts of Melbourne for over 80 years but which, in the early years of this decade, has been spreading its geographical presence.

The scientific team confirmed the presence of the ulcer in possums; confirmed that mosquitoes were the vector from possums to humans; and, ultimately, were able to identify an almost complete genome sequence of the bacterium that causes the condition. The mystery has been solved. Control of mosquitoes in the affected areas provides a means of control and, no doubt, the knowledge of the genome will enable the development of better treatments for the ulcers.

The Foreword to BASW24, First Peoples and STEM, is written by Corey Tutt, the founder of DeadlyScience. The article stresses the importance of the very long term contribution of First Peoples to STEM studies and the need for the ongoing contribution by First Peoples to STEM disciplines to be properly recognised by the science community.

The theme is further pursued in Joseph Brookes’ contribution, Indigenous Science Must be a Standalone National Science Policy, the title giving a clear indication of the argument contained within Brookes’ article.

The editors’ introduction, Voyagers, All, emphasizes the importance of story telling by reference to the Mesopotamian text, Gilgamesh, and to Australian First Nations story telling. The introduction also laments the dwindling personnel available to report science as news outlets continue to cut back on their writing staff. Despite this, as the editors note, BASW24 indicates the great work being done by the writers still working in the field.

In The Consciousness Question in the Age of AI, Amalyah Hart discusses, with very well informed speculation, the long running (but more acutely relevant) question of whether the computers will take over the world; turn on their masters; and kill us all. The article is fascinating and draws on great research. One cannot help but think, however, another relevant question is whether computers will get their chance to destroy the planet when we are doing such a great job at it, ourselves.

The most important and challenging contribution in BASW24 from a policy making point of view is Jacinta Bowler’s Science in the Balance which explains the difficult and often untenable lives of young scientists who, in the post-doctoral phase of their careers, find themselves living off short term funding provided by project research grants. The lack of security has the potential to make the young researchers susceptible to pressure to be less stringent in ensuring the integrity of their research and, also, leaves them financially insecure and unable to obtain housing loans because no lender will lend to someone whose position might come to an end within the next month or two. The article is a persuasive call for changes in the way young scientists are employed and their wages are funded.

Every contribution to BASW24 is full of interest. Many of them are fascinating. The variety of contributions provides a range of entertainment and education that makes the anthology a worthy project for publisher, editors and contributors and, most importantly, for the reader.