FEATURE ARTICLE -

Case Notes, Issue 18: June 2007

ARCHITECTS PLANS ASSOCIATED WITH DEVELOPMENT — RIGHTS?

Introduction

The High Court has considered the question of the rights to copyright (if any), in certain architectural drawings, flowing to a purchaser of real estate, in circumstances where there had been development approval given in accordance with the drawings.

Facts

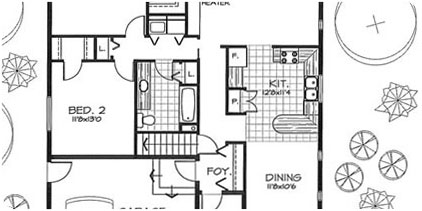

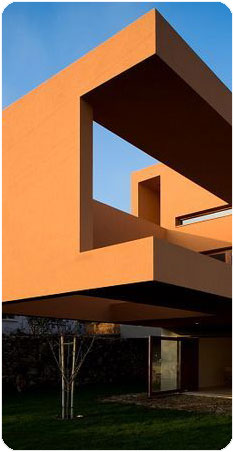

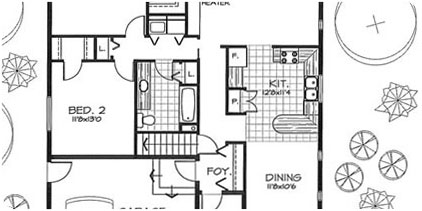

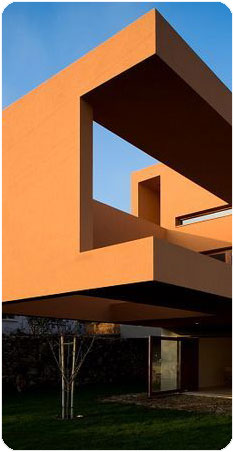

Proceedings were initiated by the owner of real estate at Nelsons Bay, in New South Wales (the ‘site’), in respect of alleged threats made against it by an architectural firm, which it claimed were groundless1. The architectural firm had prepared drawings, upon which development consent had been obtained from the local authority. The firm claimed copyright in respect of the drawings as ‘artistic works’, within the meaning of the term in s 10 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

The development had been a venture between two registered proprietors, one of which was a company in which the architectural firm’s principal had an interest. Copyright was not in dispute — the question being whether there was a licence to use them. The firm alleged that the new site owner (‘Concrete’), had no right to use the plans simply by virtue of acquiring the site. Concrete claimed, inter alia, that it had the benefit of an implied term of the contract between the firm and Concrete’s predecessors in title, to the effect that the plans could be used for the purpose for which they were created, namely the development and that the implied license extended to successors in title.

Relevantly, the immediate predecessor in title was a trustee appointed by the Supreme Court under s 66 G of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW). The application for the court’s intervention under the section arose because the proprietors of the property held the property as tenants in common and had had a falling out. Accordingly, application was made to the Court for the appointment of trustee to carry out the sale of the property. It should be noted that there were no limitations by the trustee as to the exclusion of the benefit of the architectural drawings.

Relevantly, the immediate predecessor in title was a trustee appointed by the Supreme Court under s 66 G of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW). The application for the court’s intervention under the section arose because the proprietors of the property held the property as tenants in common and had had a falling out. Accordingly, application was made to the Court for the appointment of trustee to carry out the sale of the property. It should be noted that there were no limitations by the trustee as to the exclusion of the benefit of the architectural drawings.

The failure to exclude the plans from the sale, was a major factor in the Court’s determination of whether or not a license existed in favour the owner of the site, which amounted to an authorisation within the meaning of s 15 of the Copyright Act. If in fact it was an authorisation, express or implied within that provision, then the threats were unjustified within the meaning of s 202(1) of the Copyright Act.

The provisions

Section 15 provides:

For the purposes of this Act, an act shall be deemed to have been done with the licence of the owner of a copyright if the doing of the act was authorized by a licence binding the owner of the copyright.

Section 202(1) provides:

- Where a person, by means of circulars, advertisements or otherwise, threatens a person with an action or proceeding in respect of an infringement of copyright, then, whether the person making the threats is or is not the owner of the copyright or an exclusive licensee, a person aggrieved may bring an action against the first mentioned person and may obtain a declaration to the effect that the threats are unjustifiable, and an injunction against the continuance of the threats, and may recover such damages (if any) as he or she has sustained, unless the first mentioned person satisfies the court that the acts in respect of which the action or proceeding was threatened constituted, or, if done, would constitute, an infringement of copyright.

Decision

Decision

Their Honours found for Concrete unanimously. Kirby and Crennan JJ, placing emphasis on the site being sold with a current development approval attached. This, their Honours said, indicated to a purchaser that the development consent could be used for the purpose of building in accordance with the architectural plans2. Gummow ACJ considered that if the firm were to deny consent for Concrete to use the plans, it would be pursuing its own interests which would be in conflict with the interests of the joint venture in which it was a participant.

Subject to any contrary agreement, Callinan J implied the term for the use of the plans in a contractual engagement of an architect. In this regard, Hayne J stated that the issues which arose in the case and the determination thereof, was not in his view a determination for all situations arising between an owner of real estate and an appointed architect.

The case involved a second issue for the High Court’s consideration. Parramatta had sought at trial, the disqualification of the Trial Judge on the basis of apprehended bias arising from statements made by his Honour and in respect of questions which his Honour put to one of Parramatta’s witnesses. The High Court unanimously found that there was no bias by his Honour leading to a retrial, but that his Honour was attempting by his questioning, to identify the issues for resolution.

The Court considered that the Full Court erred in entertaining submissions in relation to copyright and thereafter dealing with the issue of bias. The Full Court had upheld the appeal in favour of the architects and thereafter found the allegation of bias made out. However, Gummow ACJ noted, the relief for the finding of bias was a re-trial. By making consequential orders upon the finding on the copyright issue, no relief had been given for the finding on bias.

Relevantly, his Honour said at [1] — [3]:

Having decided that issue adversely to Concrete and disagreeing with the outcome at the trial, the Full Court went on to consider the challenge to the conduct of the trial which had been put on a quite different footing, namely, the alleged apparent bias of the primary judge. The Full Court upheld that challenge.

In proceeding in this way, the Full Court itself fell into error. The present respondents, Parramatta Design & Developments Pty Limited (“Parramatta”) and Mr Fares, were permitted to present their arguments to the Full Court on inconsistent bases. If the bias submissions were to succeed, the remedy would be a retrial. If the copyright submissions were to succeed, the Full Court would itself provide the orders which should have been made and there would be no occasion to order a retrial.

The Full Court so disposed of the appeal as to accept the bias submissions but without consequential relief. If allowed to stand uncorrected, this outcome would have the adverse consequences for the administration of justice to which Kirby and Crennan JJ refer in their reasons for judgment in passages with which I agree.

Conclusion

The case is certainly an argument in favour of purchasers of development sites in which local council approval has been given in accordance with certain drawings. Of course, this is a different situation if the vendor/seller specifically does not include the drawings in the sale, which in practice would seem an unlikely situation.

Difficulties may arise, where the architect has, in the agreement with his/her client, specified that the licence is a personal one, limited to that particular proprietor. In this regard, the architect’s association with the venture provided elements of conscience, which might not be as clear in most cases in which the question of the licence to use the drawings is raised.

Endnotes

- See s 202 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

- Their Honours’ joint judgment at [94].

COPYRIGHT IN CONTRACTED WORKS — SOFTWARE

Background

The case involved the copyrights to software improvements, between a customer and a contract service provider. The plaintiff (Generate) was a client of the defendant (Sea-Tech), in relation to the production of computer software programs which were used in the hospitality industry. The programs enabled the measurement of drink portions and the ability to integrate the bar services and gaming functions of the machines in a premises. Generate had utilised the services of another software developer to create earlier versions of the program which it updated through Sea-Tech. Sea- Tech and Generate entered into a written agreement for three years with successive twelve month terms, which the parties could terminate on one months notice. In late 2006, Sea-tech gave such notice which was accepted by Generate.

Proceedings

Generate sought interlocutory relief by motion, requiring Sea-Tech to provide copies of the source code versions of three particular programs. Although there were disputes between the parties as to certain factual matters, as an interlocutory application, his Honour considered that it was inappropriate to deal with the resolution of those disputed facts.

Decision

Einstein J granted the relief sought by the motion to Generate, making a number of orders as to confidentiality by reason of the commercial sensitivity of the material and the fact that both parties were in related industries.

Reasons

His Honour found that there was a serious question to the tried. The agreement dealt with the issue of title, but did not deal with the issue of licensing of the software. In relation to the aspect of the balance of convenience, his Honour considered that the circumstances ‘clearly favoured the plaintiff’, the main danger being to the loss of customers. His Honour did not elaborate on his observation that the circumstances clearly indicated the balance of convenience was with Generate. It is suggested that a consideration may have been, the identification by Generate of any claim it might have. In this manner the application may have yielded information in the nature of a pre-action discovery.

Dimitrios Eliades

To comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum, click here.

Relevantly, the immediate predecessor in title was a trustee appointed by the Supreme Court under s 66 G of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW). The application for the court’s intervention under the section arose because the proprietors of the property held the property as tenants in common and had had a falling out. Accordingly, application was made to the Court for the appointment of trustee to carry out the sale of the property. It should be noted that there were no limitations by the trustee as to the exclusion of the benefit of the architectural drawings.

Relevantly, the immediate predecessor in title was a trustee appointed by the Supreme Court under s 66 G of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW). The application for the court’s intervention under the section arose because the proprietors of the property held the property as tenants in common and had had a falling out. Accordingly, application was made to the Court for the appointment of trustee to carry out the sale of the property. It should be noted that there were no limitations by the trustee as to the exclusion of the benefit of the architectural drawings.  Decision

Decision