Cedric Edward Keid Hampson AO, RFD, QC was born in 1933, the eldest of three children. He attended St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace and, thereafter, graduated from the University of Queensland with Bachelor Degrees in Arts and Law.

In recognition of his leadership, academic success and skill on the rugby field, he was awarded the Rhodes Scholarship for Queensland in 1955, subsequently reading for a Bachelor of Civil Law at Magdalen College, Oxford.

Mr Hampson was called to the Bar in 1957 and commenced practice in 1959. He quickly established a prodigious practice and took Silk in 1971. His career spanned almost five decades and, for the lion’s share of that time, he was the unassailable leader of our branch of the profession. He retired from practice in 2006 after 35 years as a Silk.

Throughout his time as a barrister, Mr Hampson was known not only for his dominant presence but, equally, for the consistently high standards of excellence he set in every facet of his practice.

Among his many accomplishments, Mr Hampson was President of the Bar Association for two separate terms separated by over a decade (1978-1981 and 1995-1996), the first Chairman of Barristers Chambers Ltd, the First Chairman of the Management Committee of the Bar Practice Centre, Chairman of the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting and, from 1976 to 1978, the Honorary Air Aide-de-camp to Her Majesty the Queen.

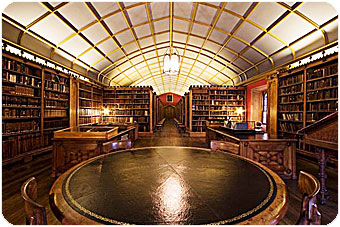

During his terms as President, Mr Hampson introduced a number of innovations to the Queensland Bar. Alongside his major achievement – the construction of the Inns of Court – he also oversaw the designing of the Association’s Crest, the publication of Annual Reports for the first time and the establishment, in 1980, of Bar News.

During his terms as President, Mr Hampson introduced a number of innovations to the Queensland Bar. Alongside his major achievement – the construction of the Inns of Court – he also oversaw the designing of the Association’s Crest, the publication of Annual Reports for the first time and the establishment, in 1980, of Bar News.

In a biographical note published in the April 2001 edition of Bar News,1 Tony Morris QC had this to say:

More than half of Queensland’s barristers were not born when Hampson commenced in practice; had not commenced to study law when Hampson took Silk; had not graduated from Law School when Hampson first became President of the Bar Association; and have known no other leader of the Bar. At one time or another, Hampson QC has led many of the State’s current judges and senior counsel. To be his junior is an invaluable educational experience – not only for what one can learn from his profound knowledge of the law, his finely-honed forensic techniques, and his wealth of litigious experience, but also for the courtesy and kindness which he shows to his instructing solicitors, his clients, and (above all) his juniors. It is inevitable that, given his preeminence within the profession, opportunities have arisen for Hampson to accept judicial appointment. That he has chosen (for whatever personal reasons) not to accept such offers when they were made has been the judiciary’s loss, but the Bar’s gain. As a great believer in the collegiate spirit which once characterised our Bar – but which, sadly, is not so evident today as it was in times past – Hampson QC has continued to maintain an “open door policy” to any member of the Bar seeking his advice or guidance. Anyone who has the good fortune to work with him, or the intellectual challenge of working against him, cannot fail to benefit from the experience. Hampson QC’s service to the Queensland Bar and the legal profession in this State is not quite unique merely for its longevity. A.D. McGill QC was in continuous practice from 1911 until his death in 1952. Sir Arnold Bennett’s career spanned 51 years, 35 of them as a Silk, although it was interrupted by a period when he left practice to pursue commercial interests. Yet few could rival the depth of Cedric Hampson’s contribution to his profession. The Inns of Court, at the corner of North Quay and Turbot Street, will stand for many years as a testament to Cedric Hampson’s organisational skills, his foresight, and (above all) his remarkable ability to cajole even the most parsimonious members of our profession to give up their dilapidated rooms in a converted boot factory, and make an investment in their own and the Bar’s future. It is particularly fitting that the dominant feature which graces the lobby to this building is a sculpture by Catharina, Hampson’s wife of 52 years. It is quite impossible to catalogue the extent and significance of Hampson’s contribution to the development of the law in Queensland and Australia, across the vast range of cases in which he has appeared at every level. A perusal of the Commonwealth Law Reports and the Queensland Reports since the early 1960s readily demonstrates, not only the huge number of cases in which he has appeared, but also the extraordinary diversity of those cases – crime, personal injuries, defamation, commercial and industrial matters, town planning cases, property disputes, and constitutional matters. One might say, as Thomas Moore said of Sheridan, that he has “run through each mode of the lyre, and was master of all.”

In addition to his many interest outside the law, Mr Hampson is a published author, having recently published his sixth novel, Occasions of Sin.2 He retired from practice in 2006 after 49 years at the Bar and, when Hearsay recently stopped by to catch up, Mr Hampson was relishing the additional time he now has to spend with his wife, prominent Dutch-born sculptor, Catharina, as well as his four children and ten grandchildren.

In addition to his many interest outside the law, Mr Hampson is a published author, having recently published his sixth novel, Occasions of Sin.2 He retired from practice in 2006 after 49 years at the Bar and, when Hearsay recently stopped by to catch up, Mr Hampson was relishing the additional time he now has to spend with his wife, prominent Dutch-born sculptor, Catharina, as well as his four children and ten grandchildren.

What follows is the transcript of a conversation that took place between Mr Hampson QC and Martin Burns SC on 3 September 2010.

University of Queensland

After finishing your schooling at Gregory Terrace, you attended the University of Queensland. How many undergraduates were there in your year?

In my time, the total Law Faculty consisted of about 40 people and, in our year, there were about 11 students and three of them left before the end of the year. One of the three who dropped out was David Malouf. He could have done it if he’d wanted to but he thought it was all very silly stuff. So we finished up with eight, but that was considered back then to be a big year. The next year was lessened in number by failures and things of that kind, and the year above that there were probably only about four or five.

What was the campus like in those days?

What was the campus like in those days?

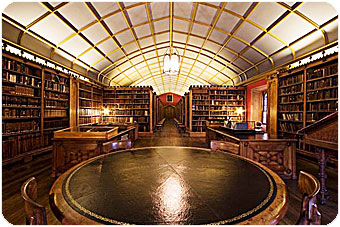

The University was quite rustic. We had only a short time before moved from George Street to St Lucia. There were great areas there that no one ever walked. What you did was you went from the Law Library down to the coffee shop. That was the place where you could do some social meandering. The centre of activities as far as the law students was concerned was the Law Library. That was the place where all the plots were hatched. In those days the law students really ran the Students’ Union. We nearly always had the President of the Union as a law student. We very often had the editor of Semper as a law student and just generally we seemed to have a big number of law students pushing their beaks into everything. So the place where these plots were made – how we were going to take over the Union and how we were going to do this and that – was always in the Law Library. There was always something or other going on in the Library. The librarian was Joy Nichols. She was there just about the whole time I was a member of the law school. She was very good at concealing the undergraduates from any evil that might be wished upon them by the authorities.

What would you get up to when you were not hard at work studying?

Oh, A few things. One of them was the great hoax that we perpetrated on the occasion of the French Government putting on an exhibition called “French Art Today”. They had very French-looking red, white and blue posters up everywhere, so John Gordon and myself conspired together to come up with a hoax. We produced two paintings and, because I was better technically than John, I did most of the painting. One was called “Pippa Passes” depicting a big Rubenesque woman on a red bicycle. The other one was an abstract with University football socks, fried eggs and all other sorts of strange things in it. So we introduced these two paintings into the French exhibition. They had a set-up in the tower at the main building and we hung the two paintings there and then had incredible fun hanging around the place and listening to all the experts comment on them.

Andy Thompson was an English teacher at the University. He was a Scotsman who made a fetish of being an outspoken person. He wasn’t so easily fooled. I recall him saying, “They’re a lot of rubbish” and holding forth to a number of people about the poor standard of the French paintings of which our two were the principal ones. But on the other hand we had quite a few people say, “Oh no, these are very good paintings. Don’t you see it?” So we had this great debate going on and it made the Courier-Mail as I remember it. It was a big joke for a few days and it was during Commemoration Week. The Commem Ball was held out at Cloudland and Nippy Power got up and imitated a pseudo-French art dealer giving a terribly funny appreciation of each of the paintings. In the next year, we cemented a statue into the ground near the main building close to where people exited from the bus going to St Lucia. We dug a hole, put the statue on a stand and placed a big sign on which was inscribed the maxim “Quicquid plantatur solo, solo cedit” (Whatever is fastened to the soil belongs to the soil). Everybody coming from the bus saw this and thought somebody must be mad putting it up. They shook their heads and pointed knowingly to the statuary.

Who were your lecturers?

In those days there was Professor Walter Harrison. He was the Garrett Professor of Law. Then we had Ross Anderson who was Professor of International Law and also Eddie Sykes. Eddie was quite a funny sort of fellow. He was quite an eccentric. He used often to wear different coloured socks, a black one on his left foot and a red one on the other. He had an Austin with a pull-up boot and, I remember one day he drove out to the University with the boot open. He just drove around, just forgot about the boot. Speaking of Eddie Sykes, about five or six years ago I gave a speech at the Law Function down at the Gold Coast and, during it, I went into some of these eccentricities that Eddie used to be guilty of and, I have to say, I believed at that time he was dead. Imagine my horror then when, at the end of the lecture, he came up to where I was sitting and said, “Ah, ha ha”.

Magdalen College, University of Oxford

You recently attended a photo shoot at the Federal Court where you and others who attended Magdalen College were assembled. How was it that you came to do the BCL there?

You recently attended a photo shoot at the Federal Court where you and others who attended Magdalen College were assembled. How was it that you came to do the BCL there?

It was coming into the fashion I think. Previous to that I think most Australians used to read the BA in Jurisprudence which is the primary law degree in Oxford. The BCL was a degree that was founded by Henry VII so it was quite an ancient degree and Bachelor of Civil Law meant Roman Law, of course, not English law. So it was extra to the idea of BA in Jurisprudence which was the English Common Law and I think it had just sat there for a long time and nobody did much about it but gradually it became the popular degree. You found a lot of great scholars doing it because they had already done a primary law degree and it fitted quite well in with the BCL. Ross Anderson was the one who encouraged me to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship and, through Paddy Donovan, to apply for Magdalen.

You mention Paddy Donovan. Was he the first to go to Magdalen College from Queensland?

I wouldn’t say that for sure, but he was the first one I knew of and he’d become a Trade Commissioner with the Australian Government in Europe. He married an Hungarian noblewoman of some kind and so, at that stage, he was based in Rome which she rather liked. She was back among the European nobility. They eventually came back to Australia and I think he then took a job at the Sydney University as a Professor in Law.

You spoke the other day with great fondness about your time at the College. It was obviously a great influence in your life?

You spoke the other day with great fondness about your time at the College. It was obviously a great influence in your life?

Oh yes, it would be very hard to dislike Magdalen. I don’t know anybody who didn’t like it to be honest. It was a college that was founded in the 15th century and consists of a number of buildings. One of them is the “New Building” which I think was built in the 16th century. They’re all very fine buildings. Architecturally they have their different styles but they seem to harmonise quite well and you enter off the High Street through the Porter’s gate and there is a series of courtyards going to your left and to your right. They are the typical buildings that you get at Oxford, although they have been better preserved at Magdalen for the reason, I think, that Magdalen was a very rich college.

Going over there must have been a big step for a young man to take?

Oh yes. At that stage, Oxford was an unknown country as far as I was concerned; somewhere on the other side of the world. I had read about it in books and so forth; it was the headquarters of King Charles during the Civil War in England. But I didn’t know much about it at all. You’d see some books which showed photographs of the places, but it was quite a different situation here. When you were told to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship, you didn’t know what it was so you had to immediately read up on that and find out what it was. You had no idea of what College to go to and it was quite a trip to get there. You had to take a ship and you were gone for two years; the two years of your scholarship. Whereas when I was on the Rhodes Scholarship Selection Committee, you came across students who had already been to Oxford two or three times before they applied for the Scholarship. They had been there and had a look to see which College they liked. Quite different in my day; we had no idea what the place looked like. We were just people who applied for the scholarship. We were all sort of little fellows, no great money at all and none of us had ever been out of Queensland. We didn’t know anyone when we arrived in England.

So you went there by ship?

Yes. It took just under four weeks. It was only when the wide-bodied planes came in some years later which took people at a lesser cost than your ship passage that air travel started to become viable. Then when they continued to get bigger and wider-bodied planes to take more people and at a price which stayed the same although the value of money fell, it became even more affordable.

So I take it that, once you arrived, there could be no thought of returning until after the course was completed?

No, you just didn’t have time for that. The only instance I can remember of that in my time was an American student. This was back in 1956. Jack Robertson was his name. His father was Assistant Secretary of State who was a big heavy hitter, as they say in the American Government. Jack had a mad idea after meeting up with a Chilean playboy who was going to study architecture at the Sorbonne. Jack decided he was going to do architecture. He was very impressionable fellow, Jack. So Jack wrote to his father and told him what he was going to do and his father said, “Come home!” So he caught a plane back to the United States and got dressed down by Daddy. He then came back, resumed his law course and finished it.

Who were the tutors when you were there?

Rupert Cross, John Morris and Guenter Treitel. Not that Treitel ever tutored me. He was a junior tutor who did all the donkeywork, but specialised in contracts.

Sir Rupert Cross was blind was he not?

Yes he was. He would have women to come in and read law reports to him and books on the law. He had a little Braille notebook and he’d make notes on that as they read. He had this fantastic memory that always amazed me. I can in particular recall one tutorial that I’d written an essay for him and I had included what I thought was a pretty smart point. In tutorials he would sit there and listen and make little notes in Braille and when I was finished he’d then comment. I thought I had got to this particular point I made in my essay by brilliant invention and he said, “Well, it’s a pity about that Hampson; you’re a bit late”. He then told me that the point had been decided against me in a case that he then gave the citation for off the top of his head. The thing was though, it was not a case that had ever been reported or mentioned in any book. I was crushed.

Did you play any sport when you were in England?

I had played rugby at Terrace, so I played rugby for the College. I also rowed in the Eights. I remember one time being concerned about not having done some portion of my academic work and being asked about that by one of the Dons from the House. I told him that I had been quite busy with Eights, but I fully expected that he would not think that to be a very satisfactory explanation. However, to my astonishment, he seemed to take it as a perfectly good excuse. I was quite surprised. I thought he was pulling my leg, being sarcastic, but I don’t think he was. I think he just genuinely thought, as people at the House would, that rowing was more important than study.

Early Years at the Bar

Did you have any family in the law before you started?

No, I didn’t, although I lived at Ashgrove down the street from Brian O’Sullivan and Len Draney. Doug McGill was around the corner. So within less than half a mile lived three practising barristers.

When you commenced practice in 1959, the Bar was relatively small?

There was something like 68, if you included the non-practising people. There was Jack Hutcheons. He was one of our eminent mentors but I don’t think he had been in Court in a long time. You know, he didn’t much like that. But if you included everybody who had been admitted and who might have had chambers around the place, I think you got to that number.

Where did you go into chambers?

I went into the old Inns of Court into Fred Cross’ chambers. Fred had quite large chambers and he also had Ray Smith there. There were two tables. Ray had been in there for a while and I heard he was moving out. I went along and saw Fred and as a result moved in with him.

Did you receive good support after you commenced?

Oh yes. They were much better in supporting each other in those days. Much better in relying upon what other people said. There was never any suggestion that I can remember of having a fight as to whether or not this had been said or not or threatening to get somebody reported for wrong conduct. Sadly, that seemed to be a frequent thing towards the end of the time I was at the Bar. You’d have barristers fighting between themselves and somehow I’d get brought into it to say who was right and who was wrong. You would have one Silk accusing the other of unprofessional conduct and the other making the same allegation. There was nothing like that when I started.

Who were the luminaries at the Bar in the early days?

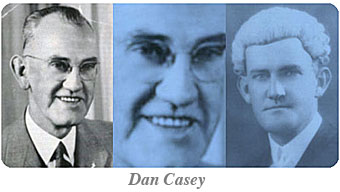

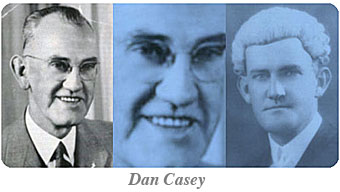

Well, there was Dan Casey, of course. He was in the criminal sphere. He was out on his own. Everybody talked about Dan Casey. He was a very nice fellow. I can remember once I won some sort of case against him, and I remarked to him that it was just luck and he said, “Never say that. It’s hard enough to win anything but when you win a case, just take credit for it, Cedric.”

What made Dan Casey so good?

What made Dan Casey so good?

First of all, he was an impressive fellow, really. If you saw him walking along the street, you wouldn’t think much of him. He always wore a three-piece dark suit and a hat, jaw jutting out and probably a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. But he had an austere air about him.

But then when he got into Court, he was quite a different fellow and even Judges wanted to stay on his right side. He just was the centre of power in the Court. He had a very good knowledge of the law. I wouldn’t say he was a great lawyer, but he was extremely good in the presentation of a criminal case, the way he would cross-examine, take objections and all that kind of thing. He was not exactly long-winded – I wouldn’t say that – but he was never short. You got the whole story, every sensible point would be made quite well.

Who do you recall practising in civil?

Who do you recall practising in civil?

The most senior Silk in my time was Mostyn Hangar. He wasn’t in the Inns of Court. He had rooms in a little building that I think has since been demolished. It was a bit towards King George Square from the old Inns of Court. Arnold Bennett was a Silk, with his own chambers, although he had been away for a while from the Bar trying to drum up a real estate business. And then among other people who were Silk were George Lucas and Graham Hart. And of course we were seeing the last year of A.D. McGill QC ending his forty-two years at the Bar.

What about juniors?

There was no one exactly of my vintage. People like Bill Pincus came along after I started but, before me, I don’t think anybody had gone to the Bar for a couple of years. I know that I was the only one admitted in my year who started practice.

Building a Practice

When you started out did you set out with the objective of taking a brief in anything that was offered to you?

Is that something that you continued until your retirement?

If I was asked, and I was available, that’s the rule. You’re supposed to take anything you’re offered.

And that of course included criminal matters?

That’s right. Yes. I applied the cab-rank rule and appeared in crime throughout my whole career.

Advocacy

Over your career, who were the advocates of note?

Well Barwick was a great advocate. I didn’t see a lot of him because when I started at the Bar he was on his last legs and of course in Sydney, but I saw him on a few occasions. He was very good because he’d got to the stage where he had a tremendous amount of confidence in his own opinions. And he was a bit of a larrikin deep down, let’s face it. He was quite impressive. Keith Aickin from the Victorian Bar was quite a good advocate. He was quite remarkable, the sort of thinker he was, but he was quite good because he got all the ducks in line all the time. You could see where he was going. One of the very best ones here was Gordon Garland. A lot of people didn’t think that, but Gordon was very precise and very good. I can remember him doing running down cases and building cases, before the Matrimonial Causes Act came along in 1959. After that, he started doing more matrimonial cases and then didn’t do anything else but towards his last years. And Gordon was a fine cross-examiner.

Well Barwick was a great advocate. I didn’t see a lot of him because when I started at the Bar he was on his last legs and of course in Sydney, but I saw him on a few occasions. He was very good because he’d got to the stage where he had a tremendous amount of confidence in his own opinions. And he was a bit of a larrikin deep down, let’s face it. He was quite impressive. Keith Aickin from the Victorian Bar was quite a good advocate. He was quite remarkable, the sort of thinker he was, but he was quite good because he got all the ducks in line all the time. You could see where he was going. One of the very best ones here was Gordon Garland. A lot of people didn’t think that, but Gordon was very precise and very good. I can remember him doing running down cases and building cases, before the Matrimonial Causes Act came along in 1959. After that, he started doing more matrimonial cases and then didn’t do anything else but towards his last years. And Gordon was a fine cross-examiner.

What makes a good advocate?

Well, first of all, knowing his work is very important. He’s got to know all the factual ups and downs. The next thing I suppose is he’s got to be careful that he has a correct attitude so far as the judge is concerned; that he doesn’t try to put one over the Court. In more recent years, people would admit to me that that’s what they were trying to do, and to me that’s unbelievable. That’s one thing an advocate’s got to be very straight with. He’s got to be straight with the other side too, so they can rely on his word. And then he has to be able to know what the law is. That’s not a great difficulty because there’s always a limited number of cases so that’s easy enough to deal with that. I think though there are some judges who go a bit mad about this. For instance, I can remember I was in a case once, and it was to do with the interference with a right of support of the land. We had an Act in Queensland that governed the position and there was a similar Act in New South Wales. I looked at the New South Wales cases because there was no Queensland case. So, in my written submissions, I referred to the New South Wales cases since they answered whatever the point in issue was. Anyway, I put that in and the judge in his judgment was rather critical of me by saying something like, “Well this was submitted on the other side by Mr Hampson, in a very short submission. He didn’t really enlarge on it.” But there was nothing to enlarge on. The point was clear and straightforward. The judge then went on to talk about it at length and agreed that what I had raised was the decisive point. But some judges want to make a big thing about what the law’s about, they want to have a big discussion going on for ages. There was no need for that. Lastly, it’s useful if you’ve got a good memory. That’s important with cross-examination; to remember pretty well exactly what the witness said. So you’ve got to have that memory going for you all the time you’re asking questions. And I think if you have all those things, if you can tick all those boxes, you’re probably all right.

Does courtesy as an advocate still have a place?

Of course. You’ve got to be courteous to the other side. And also you must be polite to the judge. In addition, I think you’ve also got to be courteous to the witness that you’re cross-examining. I think that’s so important. You don’t want people to come to Court and go away with a terrible view of what happens. After all, the only reason that we’ve got a legal profession is to deal with some expertise and professionalism with what the clients can’t really deal with themselves, because they’d probably end up in fisticuffs when they started to talk about it. So, to avoid that, you get a legal professional. So the barristers have got to be a stage above the clients’ barneying, and I think that’s important. If you play the man rather than the ball, you’re taking your eye off the ball. It’s very risky doing that. You might very well end up losing the case because of it.

Written Advocacy

You mentioned written submissions. What do you think of the relatively modern trend towards written, as opposed to oral, advocacy?

I think they probably overdo the move to written submissions, because you have to bear in mind that it takes a long time to do a good set of written submissions. The traditional way is to get your case ready and then you can present it orally. Sometimes, you might use a document that presents the argument in a dot point sort of form. But then you would always get up and speak about it. To put all that in proper submission form, it probably adds days to it by the time you set it all out. So that’s one thing that’s quite bad about because it adds a lot to the cost of litigation. And I don’t know what the advantage is so far as the judges are concerned. Why you can’t sit there with a pencil and record your points is beyond me. If that fails, you are getting a transcript of what is said anyway. So I really don’t know why they need written submissions.

Specialisation

What then do you think about the trend towards specialisation where some barristers appear to set themselves up as experts in one particular area?

I don’t think it’s true specialisation myself. Really what you’re trying to do is to cut the eyes out of whatever briefs might be available and really reject all the rest because you like doing that work. I also don’t think you would become a very good barrister if you do that. You sometimes see that with people who specialise in work of some kind; they don’t really know their rules of procedure in Court and they can also be pretty hopeless at cross-examining.

Click here to continue.

Footnotes

- The full biographical note is reproduced on the Lex Scripta website – http://www.lexscripta.com/articles/hampson.html.

- For the full catalogue of Mr Hampson’s publications, go to – http://www.cedrichampson.com/books.html

During his terms as President, Mr Hampson introduced a number of innovations to the Queensland Bar. Alongside his major achievement – the construction of the Inns of Court – he also oversaw the designing of the Association’s Crest, the publication of Annual Reports for the first time and the establishment, in 1980, of Bar News.

During his terms as President, Mr Hampson introduced a number of innovations to the Queensland Bar. Alongside his major achievement – the construction of the Inns of Court – he also oversaw the designing of the Association’s Crest, the publication of Annual Reports for the first time and the establishment, in 1980, of Bar News. In addition to his many interest outside the law, Mr Hampson is a published author, having recently published his sixth novel, Occasions of Sin.2 He retired from practice in 2006 after 49 years at the Bar and, when Hearsay recently stopped by to catch up, Mr Hampson was relishing the additional time he now has to spend with his wife, prominent Dutch-born sculptor, Catharina, as well as his four children and ten grandchildren.

In addition to his many interest outside the law, Mr Hampson is a published author, having recently published his sixth novel, Occasions of Sin.2 He retired from practice in 2006 after 49 years at the Bar and, when Hearsay recently stopped by to catch up, Mr Hampson was relishing the additional time he now has to spend with his wife, prominent Dutch-born sculptor, Catharina, as well as his four children and ten grandchildren. What was the campus like in those days?

What was the campus like in those days?  You recently attended a photo shoot at the Federal Court where you and others who attended Magdalen College were assembled. How was it that you came to do the BCL there?

You recently attended a photo shoot at the Federal Court where you and others who attended Magdalen College were assembled. How was it that you came to do the BCL there?  You spoke the other day with great fondness about your time at the College. It was obviously a great influence in your life?

You spoke the other day with great fondness about your time at the College. It was obviously a great influence in your life?

What made Dan Casey so good?

What made Dan Casey so good?  Who do you recall practising in civil?

Who do you recall practising in civil?  Well Barwick was a great advocate. I didn’t see a lot of him because when I started at the Bar he was on his last legs and of course in Sydney, but I saw him on a few occasions. He was very good because he’d got to the stage where he had a tremendous amount of confidence in his own opinions. And he was a bit of a larrikin deep down, let’s face it. He was quite impressive. Keith Aickin from the Victorian Bar was quite a good advocate. He was quite remarkable, the sort of thinker he was, but he was quite good because he got all the ducks in line all the time. You could see where he was going. One of the very best ones here was Gordon Garland. A lot of people didn’t think that, but Gordon was very precise and very good. I can remember him doing running down cases and building cases, before the Matrimonial Causes Act came along in 1959. After that, he started doing more matrimonial cases and then didn’t do anything else but towards his last years. And Gordon was a fine cross-examiner.

Well Barwick was a great advocate. I didn’t see a lot of him because when I started at the Bar he was on his last legs and of course in Sydney, but I saw him on a few occasions. He was very good because he’d got to the stage where he had a tremendous amount of confidence in his own opinions. And he was a bit of a larrikin deep down, let’s face it. He was quite impressive. Keith Aickin from the Victorian Bar was quite a good advocate. He was quite remarkable, the sort of thinker he was, but he was quite good because he got all the ducks in line all the time. You could see where he was going. One of the very best ones here was Gordon Garland. A lot of people didn’t think that, but Gordon was very precise and very good. I can remember him doing running down cases and building cases, before the Matrimonial Causes Act came along in 1959. After that, he started doing more matrimonial cases and then didn’t do anything else but towards his last years. And Gordon was a fine cross-examiner.