Alternative Dispute Resolution

Another relatively modern trend is alternative dispute resolution. What do you think about that?

Well, if you look at fundamentals, the first point about it was that settlements occurred in my day between barristers opposing each other. They would settle on the Court steps, or the steps of the Inns of Court, and they’d know what should be settled and they would then settle it. You’d have the solicitors preparing a brief – that was their function – and you’d have the barristers prepared to argue the case in Court. Then, when it was properly prepared, proper thought could be given to settling it. Now what did you have in place of that? What you have are solicitors who as soon they get the case, you know, they work for the case to be mediated right from the start. This is before they’ve looked at it properly and discovered whether there are any points that are difficult or anything of that sort or before they get an opinion from anybody. Indeed, the practice of getting counsel’s opinion seemed in my last years at the Bar to be terminally ill. I just don’t think the solicitors are doing their job and, with mediations, they are being given a very attractive way of getting out of doing their job properly, of doing the hard work. They say, for example, “Well, this is a personal injury matter and the fellow has lost his leg and he should get $50,000” or whatever it happens to be. That’s just off the top of the solicitor’s head. That’s what they’re going to go for and then somebody or other becomes the mediator. So the solicitor gets there for the mediation. He doesn’t know if there are all necessary proofs from the client. He has some reports from doctors. He has a bit of stuff. He also probably has several case files full of things like the fellow’s bank statements years before he had the accident. Completely irrelevant stuff, but he thinks it all needs to be briefed to the barrister because if he doesn’t he thinks he might be sued for negligence. Well, you know the thinking; someone might find it relevant so I better send it up. Anyway, I can copy it all and that justifies part of my fees. The mediator, he mightn’t be much better briefed than the barristers are, and he’s got a range that goes from, say, $10,000 to $60,000. So he gets some sort of figure and he says, “Well, I think that would be a good figure”. Now what’s happened of course is that you will find there’s been a breach of ethics by the solicitor because he hasn’t really tried to get the best figure for his client. He doesn’t really know what the best figure is and that is because he hasn’t prepared the case anywhere near enough to know any better. Then if the solicitor is a bit crooked, he just goes one stage further than what I’m talking about and he says, “Well, I reckon my costs in this are $50,000” or whatever it is. Some figure just jumps out of the air. So he says to himself, “I need to get that from the settlement”. So once he gets to that figure in the mediation, he’s happy. He is then in conflict with his client. He wants the client to accept the offer because his fees will be squared away. So, the primary motivation for the mediation has become an exercise in getting the solicitor paid rather than compensation for his client.

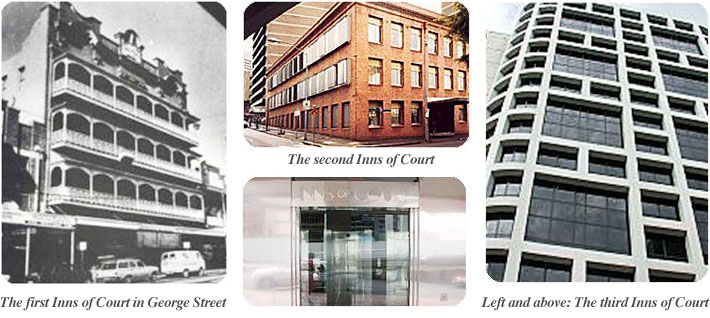

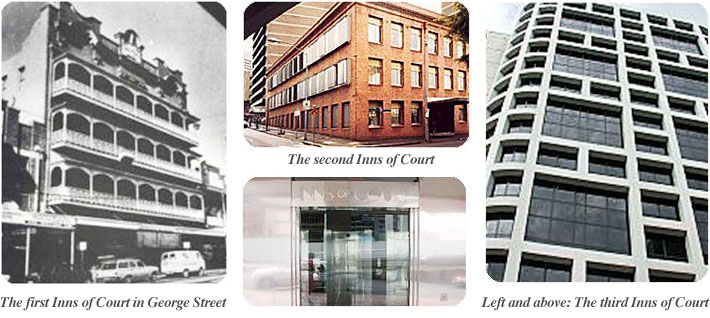

Construction of the Inns of Court

Amongst your achievements as President was the instrumental role you played in the construction of the Inns of Court. Persuading so many barristers to agree on that proposal must count as one of your greatest feats of advocacy?

Amongst your achievements as President was the instrumental role you played in the construction of the Inns of Court. Persuading so many barristers to agree on that proposal must count as one of your greatest feats of advocacy?

Well, I don’t think there were too many speeches about it. There were a couple of meetings but I think that it was probably a question of getting the building going. We had a couple of meetings, trying to get with SGIO, in fact, some development up and running. It didn’t succeed but there were discussions at that stage and I reckon there was a very small majority in favour of doing something.

We then went to a stage where we had to consider what we were going to do quite seriously and it was at that stage, I think, that it got going. We put together a book which showed you pictures of how it would be and so forth and the documents you’re going to sign for shares, different figures showing what would happen with that and so on. And we then had a system of trying to get people individually to come along and have a talk and show them these things. So we slipped on then, I reckon, to the next level where we had about 70% in favour of it. Some of the opposition was quite ridiculous. For example, one senior junior was a member of the Irish Club. He’d go down there quiet often to drink and as a result, he got this strange view that he was some sort of property expert. He said, based on what he thought the Irish Club was worth, that our site was worth at least $10 million. Well while you couldn’t get him to change his mind on that, the views he expressed caused a lot of people to say, “Look that’s a bit ridiculous”. So we found that our support got higher as a result of the stance he took and, in the end, we got about 90% in favour. Then the important thing was to show that we were doing something. At the Bar there is always talk about what we’ll do, but not much action. We’re great men for the defendant. We can find reasons why it mightn’t work; you know, the sky might fall in, all sorts of things can happen. But we overcame all of that and got moving with it. The only unfortunate thing about the whole business was that we never got enough people to go into the building next door. We could have bought that for something like $300,000, it was a real steal. But we’d expended all our energy. So we never went ahead unfortunately. If we had about a year or so living in the new building, we probably could have got that one too.

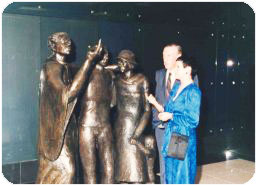

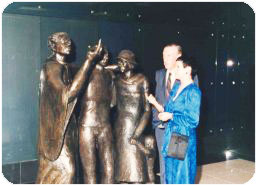

The statue, “Advocacy”, that we see in the foyer of the Inns was sculpted by Mrs Hampson. What was the story behind that?

The statue, “Advocacy”, that we see in the foyer of the Inns was sculpted by Mrs Hampson. What was the story behind that?

I think it was just an idea that I introduced to the directors that we should have something significant. There was a philosophy that was around at that stage that every new building had to spend a percentage of its total cost on artworks. So I thought the best idea really would be if we got a statue made. And, of course, the directors didn’t know much about that so I said, “Look, I’ll get my wife to make a model. You can see what I’ve got in mind”. They agreed, and Catharina produced a model. The directors liked the model and what you see in the foyer is the result.

The statue is of a barrister, a man, a woman and a child. Is the barrister you?

The statue is of a barrister, a man, a woman and a child. Is the barrister you?

At the time, I didn’t think it was intended by Catharina to be anybody to be honest. More recently, she disclosed that the barrister’s head was inspired by a wax-bronze bust she made of me prior to the making of ‘Advocacy’. I was completely unaware of that until then. Apparently, certain changes were made by Catharina to avoid the possibility of an exact likeness to me and she also said that the woman and child were inspired by the writings of Patrick White.

It conveys a wonderful impression of a barrister — someone who is helping others?

Yes. That’s right. I think it says a lot.

Before we leave the topic of the Inns of Court, it would be remiss of me not to seek your help to solve a mystery. After entering the lift on the ground floor of the Inns, one finds that you travel very quickly to Level 5. The reason of course is that Levels, 1, 2, 3 and 4 seem to have vanished. Can you shed any light on that?

They certainly got lost at some point, but I don’t know how they got lost. I think it was something inspired by the builders. They also had a theory that was current at the time that you shouldn’t have a Level 13 in the building either. And I said, “Won’t that be funny though?” But they didn’t think it was funny at all.

One of the theories that abounds is that, by starting the floor count at 5 instead of 1, the Inns would end up having a higher numbered top floor than the building which then housed the Bar in Sydney. In that way, so the theory goes, the Inns would be seen to be one floor higher. Could that be correct?

It might have had that effect but it wasn’t conscious. I can remember people talking about it at the time, but that’s about all. The builders gave us the floors and we just took them.

Preparation

How did you prepare for a case?

Well, these are counsels of perfection, but what I tried to do was to know every fact there was about the case. I’d know every word that was ever written or spoken about the case that could be relevant because you never knew what would come up. For instance, in a motor vehicle accident personal injuries case, there might have been a trial in the Magistrates Court for the driver of the car for driving without due care and attention. If so, I would want to summons the record and read every word of it. Sometimes you’d read the record and there’d be something that you’d find that was quite important. So you’d, in effect, try to find out everything that was connected to the case. Then in the process of doing that reading, I would write down all the facts. I used to have a system of exercise books, and I’d start off on a page and I’d write down what I thought the facts were. To continue the personal injuries case example, I would start off with the plaintiff born on such and such a day, where he went to school, his work experience, history, when he got married and all that sort of thing right up until the date of the accident. Then he’s in hospital and this happened to him or whatever. So the idea was that you ended up with a timeline of the whole thing. In the same way, I would put down how the accident happened. He was driving a car this night or whatever it was, the whole sequence of the accident – relying on this statement and the statements of other witnesses and so forth. You’d put all that down. And very often the tabulation of all those facts would be very revealing because they’d tell you something that wasn’t there. And you could go and search for that and get that right. Then you had a feeling that you had all the facts on his life along with all the facts on the accident. If there was some other thing that was important it needed to be dealt with. Supposing that the big thing in the case was that he was expected to get a promotion. If so, you might make that a little story in itself. The only other thing was that, as you read the statements of each witness, you’d write out in some convenient place any important things to get from him. For example, his statement might have been silent as to whether the lights were on, or not, so you’d put that down and get that during your conference with that witness. When you had all those things together, and patched up all the holes which were in the account of them, you were probably ready to run from the factual side of things.

What you are describing is of course simply hard work?

Oh yes, it’s a lot of hard work. There’s no doubt about it. It takes a long time to prepare something properly. But you have to remember there has to be a limit to this because you would keep going and going and going and end up with more manila folders than you could possibly cope with. So at some stage you’ve got to say, “Well, that’s enough, I’ve answered the question.” I’m not going to ask the solicitor to get in touch with the police in Perth to see whether when he was living there for two years or something, unless it’s a terribly important point. So there’s a question of judgment to be exercised as well. You have to know when enough is enough.

Work and Life

Because good preparation is a function of hard work, I expect you worked many long hours over your career?

Because good preparation is a function of hard work, I expect you worked many long hours over your career?

Yes. Quite long hours. And you never really catch up. A good example of that was one Easter. I decided I’d catch up. I had opinions and various things I hadn’t done. I said to Catharina, “Well, you do something with the kids over Easter because I’m going to work every day”. So that gave me five days to catch up. And I worked damn hard. I got in at chambers at six o’clock and came home about ten at night and got it all done. I was really pleased and thought that it was a very good exercise. During the next week the opinions or whatever I had done were typed up and sent out. However I found that within a fortnight I was as far behind as I was before I started at Easter. So that’s paperwork – it’s just something you could never really ever get on top of.

Did you work much at home?

I would always try to be home in time for dinner with the family. But then I would always go away and read things like transcripts and all that sort of stuff at home. Mainly reading.

You always seem to be involved in many other things outside the law. Is it important to a barrister to have outside interests?

Well, I think its desirable. A fellow who didn’t have many outside interests was Arnold Bennett. He was interested in his profession and that was about all. He was pretty light on the other side and I think – I hesitate to use the word — but I think it probably makes you less happy. You don’t have a full enough grasp on the world to be happy about it. I think that’s what happens.

Do you think leading a more rounded life might make you a better barrister?

It’s hard to say, isn’t it? There are some awful people in the Famous British Trial series I can remember reading about, English barristers, who were terribly narrow-minded, but probably effective advocates. However they seemed to be very unattractive personalities. I just don’t know whether if you had them interested in something else whether they’d improve. You would think they should but I just don’t know.

Quality of Briefs

Did you notice any change in the quality of the briefs delivered to you over your years in practice?

Yes. One of the things that increasingly happened in my last years at the Bar was solicitors in a personal injuries case would send you up the bank statements of the client if something had happened where his earnings might be affected. They’d be of no use at all because you could easily accept the fact that he used to earn $20.00 a week or something. But they sent it nevertheless. So we got to a stage of bad briefing. So much of what some solicitors would send up was completely misconceived. On the other hand, there were always good solicitors who knew how to prepare a proper brief. A very good solicitor, particularly on the personal injuries side, was Mick Pattison. He died quite a few years ago but he was a principal of Pattison & Barry. He prepared a very good brief. He would read all the material first and then prepare the brief as a result of his reading of it. You didn’t get irrelevant documents from him. You got all the relevant documents as well as things that he didn’t have at first but had gone and searched for. You could present a case from his briefs quite well in Court. Photocopiers have led to the problem of bad briefs. Early on, if you had to copy a brief then the way it was done in those days was quite expensive. So the photocopy machine was an answer to that problem because you just could just run everything through. In the old days, the briefs were much thinner and much more helpful. People would think about what they were going to send before the brief was compiled.

Judicial Appointment

Despite a long and phenomenally successful career, you never accepted judicial appointment. Why not?

Well, for one thing, a number of people who were appointed to the bench had in fact been pupils of mine and I didn’t sort of feel like coming in and, well, standing in line. So, that was certainly a thought. And I’d say that it’s also a very difficult life being a judge because of the fact that you’re in that line. You’re circumscribed in so many ways as to what you can or cannot do. You shouldn’t go to a bar or you shouldn’t do this or that. That wasn’t really for me. I also got immense satisfaction in helping people and I think there is sort of less scope to do that as a judge. So all told, an appointment wasn’t terribly appealing to me personally. You have to remember there are quite a number of problems with being a judge. You’re supposed to make a judgment and decide for A or B. Now that’s probably straightforward enough, but there’s a lot of things you’ve got to get over to do that fairly. You’ve got to get over the prejudice you might have for or against one party or another because one presents better or whatever. You’ve got to get over that. And then you might have to do a written judgment. So, you enter into another problem then because that’s going to be there for everybody to read. So unless you want people to laugh at you and say you’re a bit of a fool you’ve got to try hard to make that read quite well. Remember it’s not a majority of people who can write well on the law. There are also different ways of writing. For example, when I started writing novels and got published, I noticed quite early on in the piece that I developed a system of writing which I might call legalese which is the way that lawyers write. When I was a barrister I was trying to cover all points which is absolutely boring for anybody else to read, so I had to break all that up and try for a different style of writing. So I quite deliberately changed my style of writing because otherwise no-one would have read it. But I don’t really believe a lot of judges appreciate that. I think some of them believe that they’re good writers despite all this legalese they’re writing.

Is a good judgment a short judgment?

As long as you make the necessary points in it. And that in itself raises the question again of your discretion as to what the points should be. But it should be a short judgment consistent with covering the points. Now there are a lot of judges who think they’re going to write themselves into immortality by spending pages and pages going on about one point or another. Unless you’ve got a good writing style to keep the people’s interest up, they won’t read it. They’ll just go right to the end and see which way you’ve decided. That’s all they’re interested in. Even though, when you wrote it, you thought it was going to be fascinating.

All right, let’s turn to judicial appointments generally. The system for appointments remained largely unchanged throughout your whole career. Does it work well or do you think there is a case for an independent body to make appointments in preference to the Executive?

I don’t think an independent commission should make the appointments but I don’t suppose there is any harm in having an independent commission which approves people. In other words, to say whether someone is qualified or suitable or otherwise fulfils criteria.

That would get rid of some of the real rat-bagging in appointments; if you had some standard introduced. Because I think it is quite clear that the politicians have got no idea of what the standard is. They’ve got no idea really of whether a person is good or not good. When I was President of the Bar Association on several occasions I can remember the Attorney-General didn’t have any idea who to appoint. He’d ask the senior officers in his Department and they wouldn’t be too sure either. He would then ask me in my capacity as President and my practice was to give two names. I’d say, “A or B”. And both would be quite good. I would do that after I had rung A and B and said, “Would you take the appointment if you were offered it”. And in every case in my time the Attorney-General appointed one of the two I nominated. But maybe some sort of body to vet the applicants is needed particularly these days where there seems to be so many appointments in all sorts of courts and tribunals. It didn’t matter so much years ago.

How many judges were sitting when you started at the Bar?

I think there were about eleven Supreme Court judges. No District Court judges. Just Supreme Court judges and the Magistracy, practically none of whom that I can remember were legally qualified. When the District Court commenced, it took Grant-Taylor and Andrews. At a later stage it took Reginald Carter. So there were two original appointments and then Carter came along a little later so you had three and they went along for some time with that until they started to appoint more.

Motivation and the Decision to Retire

Over a career of almost 50 years as a barrister and, for most of those years as leader of the Bar, how did you maintain your motivation?

Well, I wonder that a bit myself because when I gave it up and started to look at myself over the last couple of years, I thought well, my performance might be falling off, you know, and it probably was. But I wasn’t really conscious of it. Then I asked the very question, had I had enough? Because I thought if I had had enough of it you would fall off in performance. I had just got to that stage of thinking when I had a couple of significant operations that seemed divinely inspired to put me out of business. The first operation was for an aneurism growing in the abdominal aorta and the medical textbooks said if that if it grew to a certain size they should operate because it could break at any time. The doctor said, well, you know, “You can please yourself whether you have it or not but, if it did break and you are a long way from hospital, you’d be in trouble because there’d be a lot of bleeding.” So he put it to me that it was sort of six that I should have it and four that I shouldn’t. So I had that one and it was a pretty massive operation, so I was off for a while with that. I was still going into chambers but I wasn’t doing the work that I did up to that time. And then I had the next operation because my doctor maintained that I had a stroke. I thought he was being a bit hysterical to tell you the truth, but he reckons he found a little clot. I don’t know whether that was right or not to be honest, but that required another operation although not as bad as the first one. And it was about at that stage I was starting to think well, you know, what’s the point of really keeping on with this if in fact the doctor’s right? Maybe I’ll have another stroke, and the only way you can tell whether you’re going to have another one or not is just to live and see whether it happens. Anyway, I haven’t had another one.

Do you miss practice?

I don’t really think so, no. I think it’s a young man’s game and I think if one is completely honest one should really say that. When you start at the Bar it’s exciting and all that kind of thing. There’s a fight for work, there’s a fight to get ahead and that continues as you get successful. You’re sort of at the top of the tree and you’re still kind of fighting to preserve yourself up there. To some extent motivation also depends on the type of cases you might be involved in at the time. Some cases you can’t wait to get your hands on. Others seem less so. So you’ve got to give yourself a kick in the bum with those. However, when you get to about 60 the old body’s not what it once was and it’s getting a bit harder. You don’t see that at the time but looking back, I can see that was the way it was going.

The Future of the Bar

Is there a future for the Bar?

I don’t know. There is so much messing around with it, I’m afraid that you just don’t know where it is. I think the future is a little uncertain. I look at that fellow who writes for the Australian. He writes about judges – they’ll get a mention – and solicitors and big firms but barristers, I don’t recall them being mentioned much at all. I only mention that so as to indicate that you don’t get much publicity any longer whereas many years ago they couldn’t write such an article unless you had Barwick in it and all that sort of thing.

A number of lectures were given a couple of years ago for the New South Wales Bar Association that are collected in a book entitled, “Rediscovering Rhetoric”. Justices McHugh and Kirby gave two of those lectures and used them to debate whether there had been a “decline in the barrister class”. McHugh was for that notion and Kirby, perhaps not surprisingly, disagreed. Kirby argued that, in years gone by, big cases attracted a great deal of interest from the public. They were closely followed by the press and reported intensely. He maintained that court cases were a form of entertainment whereas now, there are different calls on our time and more instantaneous or attractive forms of entertainment. Do you have a view about that?

Probably untrue. It’s a bit like cases in England. There was a time in England where murder cases were the extreme amusement of English people and you had lots of barristers who were quite famous because of the murder cases. Now I suspect that doesn’t happen any longer and that’s partly s a question of how well it’s written, how much time they put into it and all that sort of thing. Because you’ve certainly still got the murders and, at times, there’s great interest in them but I suspect that’s what’s happened. I suspect the same thing here too, that you don’t have the blokes who could write the way they used to. For instance, I used to go up to the Maryborough Magistrates Court – that’s a long time ago now. There was a solicitor up there, Sheldon, who used to brief me quite a bit, and also Gerald Pattison in Brisbane. He had a house up there. So I used to go to Maryborough quite a bit back then. So, in the earliest days I went there, there was a reporter who worked for the local Maryborough paper and I think he syndicated a bit of his stuff down to the Courier-Mail. He was just terrific, and far better than the blokes they had down at Brisbane. He was extremely good. There was one case I can remember that was a bit out of the ordinary. It concerned a bloke who’d got injured when working at one of the factories they had there. Something came off a crane I think. Anyway, this journalist reported the case and he had it dead to rights exactly. You read the report and it was completely correct. And you have to remember that in those early days we used to accept reports like that as being law reports for the purpose of who the people were, what happened, who they were in court and so on. So if you still had journalists like that, I’m quite sure that you’d have great interest in big cases.

Memoirs

You have recently published your sixth novel, Occasions of Sin. Are there any plans afoot to publish your memoirs?

You have recently published your sixth novel, Occasions of Sin. Are there any plans afoot to publish your memoirs?

Well, (my daughter) Edith is pressing me on that because I said I’d do it and I haven’t got around to it. But I must say I’m a little bit afraid of doing too much while people are still alive. So that’s just a bit of a concern.

That presents a bit of a conundrum of course?

Yes. If I wait too long, there may be no one left to read it.

Ascot, Brisbane 3 September 2010

Photos courtesy of The Supreme Court Library.

Amongst your achievements as President was the instrumental role you played in the construction of the Inns of Court. Persuading so many barristers to agree on that proposal must count as one of your greatest feats of advocacy?

Amongst your achievements as President was the instrumental role you played in the construction of the Inns of Court. Persuading so many barristers to agree on that proposal must count as one of your greatest feats of advocacy? The statue, “Advocacy”, that we see in the foyer of the Inns was sculpted by Mrs Hampson. What was the story behind that?

The statue, “Advocacy”, that we see in the foyer of the Inns was sculpted by Mrs Hampson. What was the story behind that?  The statue is of a barrister, a man, a woman and a child. Is the barrister you?

The statue is of a barrister, a man, a woman and a child. Is the barrister you?

Because good preparation is a function of hard work, I expect you worked many long hours over your career?

Because good preparation is a function of hard work, I expect you worked many long hours over your career?  You have recently published your sixth novel, Occasions of Sin. Are there any plans afoot to publish your memoirs?

You have recently published your sixth novel, Occasions of Sin. Are there any plans afoot to publish your memoirs?