The mediation process inevitably involves the passing of thoughts, views, information and argument from one party to another. This may be done directly by a party under the mediator’s control and supervision, or it may be done indirectly through the mediator. And it may be done orally or in writing.

Parties are almost always told by the mediator that such communications are “in confidence”. However in voluntary mediations (not ordered by the court) this is not absolute. Unrestrained by the legislation covering court-ordered mediations, the courts will admit evidence when it is in the interest of justice to do so — a natural product of the conflict between:

(a) the need to maintain confidentiality in order to encourage the parties to settle their disputes; and

(b) the courts’ overriding aim to achieve justice between the parties on all issues.

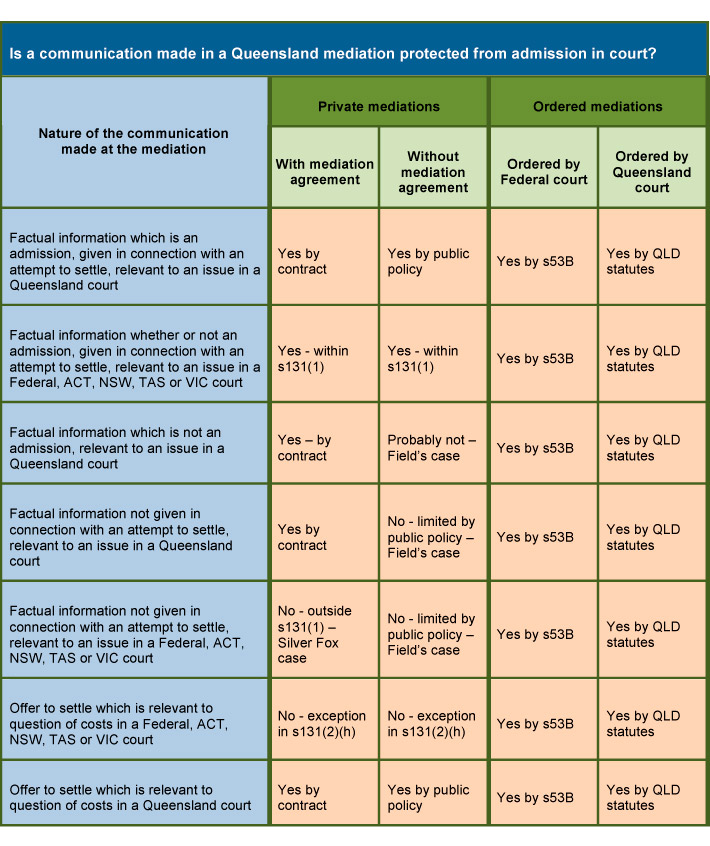

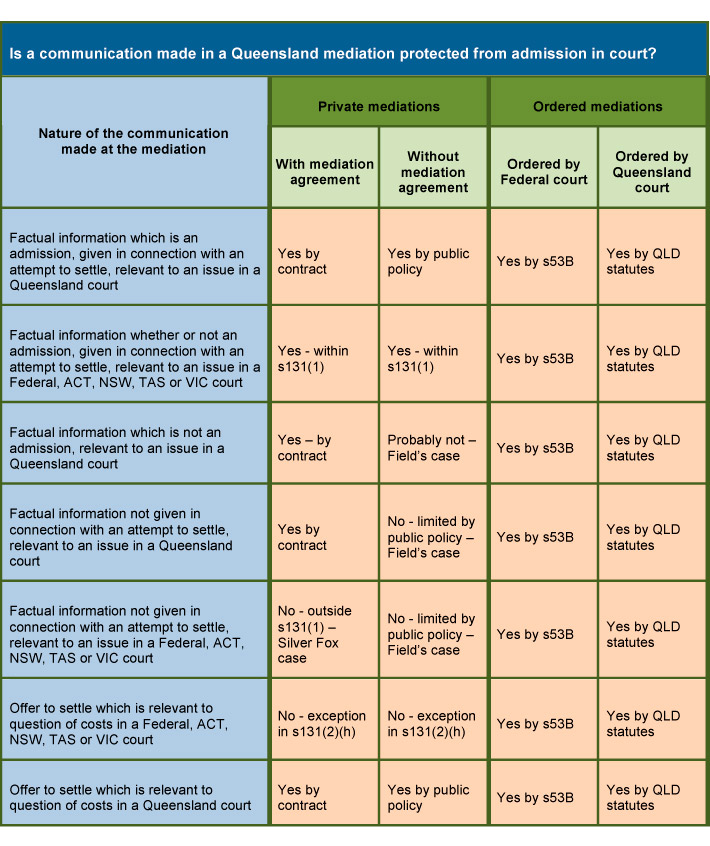

Where the line is drawn in practice is not obvious and is affected by the following factors:-

- the nature of the communication

- whether the mediation is ordered by the court and if so which court

- before which court the question of admissibility is tested

- what is said in the mediation agreement

There is a useful table at the end of this article which demonstrates how these factors work and interact. But first I need to examine some of the things in the table.

How confidentiality arises

It can arise:-

1. As a matter of law from the without prejudice nature of settlement negotiations.

2. By agreement between the parties in:-

(a) dispute resolution clauses in contracts made before any dispute has arisen: these may require the parties to resolve disputes by mediation or other types of alternative dispute resolution before resorting to the courts;

(b) mediation agreements which govern the dispute resolution process agreed to by the parties: normally it would be signed by all attendees to discussions;

(c) settlement agreements following successful negotiations: normally signed at least by the parties to the dispute.

3. By statute, that is:-

(a) section 131 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (in a case before the Federal or ACT courts) and similar legislation in NSW, TAS and VIC (in cases before those courts);

(b) section 53B of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 for Federal court ordered mediations;

(c) sections 39-41 of the Magistrates Court Act 1921, ss107-109 of the District Court of Queensland Act 1967 and ss 112-114 of the Supreme Court of Queensland Act 1991 for Queensland court ordered mediations;

(d) section 83 of the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal Act 2009 for QCAT ordered mediations;

(e) section 36 of the Dispute Resolution Centres Act 1990 (Qld) for DRC mediations.

4. In the case of the mediator’s own duty of confidence, by standards or professional rules (outside the scope of this article).

1. “Without prejudice” negotiations

Statements made during negotiations expressed to be “without prejudice” have a certain degree of protection from disclosure at common law.

Even if not expressed to be without prejudice, negotiations carried out in a genuine attempt to settle a dispute will automatically achieve the same protection. As explained by the House of Lords in Rush & Tompkins v GLC [1989] AC 1280, this is a rule of evidence established as a matter of public policy. The main reason for the without prejudice rule is to encourage compromises by avoiding embarrassment to a party if negotiations fail and their statements made during the negotiations are later put in evidence: Village/Nine Network v Mercantile Mutual [1999] QCA 276 at [18].

There is approved dicta limiting the without prejudice rule to “admissions” which are made with a purpose “connected with” or “reasonably incidental” to the settlement of the action: Field v Commissioner for Railways NSW (1957) 99 CLR 285.

Field was a claim for damages for personal injuries. The plaintiff gave an account of the accident to a medical expert who examined him for the purpose of the proceedings. Evidence of this account was admitted at the trial. It was held to be not reasonably incidental to the negotiations for settlement of the action and therefore was not privileged under the without prejudice rule.

If the dicta in Field is followed strictly it excludes from common law privilege anything which is not an admission or other communication made with a purpose “connected with” or “reasonably incidental” to the settlement of the action.

Several cases have grappled with the distinction between such communications and other types of communications made for other purposes, for example:-

In Canvas Graphics v Kodak [1994] FCA 282 the court admitted evidence of a demonstration by Kodak in which they attempted to show the quality of a machine supplied to a customer who refused to pay for it. However, evidence was excluded of what was said during the demonstration since that might amount to an admission.

In GPI Leisure Corporation Ltd (in Liquidation) v Yuill (1997) 42 NSWLR 225 the court admitted a letter marked “without prejudice” which indicated that if the litigation could be dealt with in some practical way the writer was “open to suggestions”. The letter did not actually suggest how the dispute could be settled, so it was not connected with an attempt to negotiate a settlement.

In Collins Thomson v Clayton [2002] NSWSC 366 the court admitted a letter in robust terms which analysed the various proceedings between the parties and forecasted their likely outcome, and then rejected the offers in question and observed that the party had substantially nothing to lose by prosecuting the various proceedings, and stood to gain in various respects. The letter was not connected with an attempt to negotiate settlement.

In Airtourer Co-operative v Millicer Aircraft Industries [2004] FCA 948 the court admitted a statement made by a party that it could not consider any offers of settlement because it was insolvent. This was not connected with an attempt to negotiate settlement.

It has been debated whether it is right to confine the common law without prejudice rule to admissions or whether it should also extend to other types of communications such as statements of fact or arguments divulged to the other side during without prejudice discussions.

Hasluck J in Chandler & Ors v Water Corporation [2004] WASC 95 pointed out at [49] that parties cannot speak freely at a without prejudice meeting if they must constantly monitor every sentence. He held that the without prejudice rule extends to all bona fide without prejudice statements which touch upon the strengths or weaknesses of the party’s cases or places a valuation on a party’s rights.

Barker J in Williams -v- Nicoski [2003] WASC 131 took a similar but perhaps wider view. At [312] he said: “for my part, I would accept that the so-called without prejudice privilege extends to all communications in the course of negotiations designed to resolve a dispute which, it may be considered were “fairly incidental to the purposes of the negotiations”.

The without prejudice rule will not apply if its application will result in the court being misled as to the true facts: a point recently reiterated in Apotex Pty Ltd v Les Laboratoires Servier (No 5) [2011] FCA 1282 at [42].

In Biovision v CGU Insurance [2010] VSC 589 Judd J set out some other examples1 when the without prejudice rule does not apply.

In Abriel v Australian Guarantee Corp [2000] FCA 1198 it was conceded by counsel (and not determined by the court [5]) that events occurring in the mediation were admissible in evidence in a case where there was an allegation of unconscionable conduct in reaching the settlement.

2. Agreement

Usually a mediation agreement will make confidential and attempt to restrain disclosure of all oral and written communications made by a party during a mediation or in preparation for it, and whether made to the mediator or directly to the other side. This will not be limited to communications made with the aim of trying to settle the dispute.

It is justifiable to ask the parties and all attendees at a mediation to agree such terms in an attempt to free the parties from concerns that statements they make during the mediation process may be used by the other side should negotiations fail.

However, mediation agreements are not necessarily sacrosanct. It would appear from Silver Fox Co v Lenard’s (No 3) [2004] FCA 1570 (below) that statutory provisions may override confidentiality agreements made between the parties.

Ian Hanger AM QC has expressed the view that a party to a mediation agreement would not be in breach of contract or confidence in disclosing a threat to commit a serious criminal act. He also noted that the Victorian Law Institute was of the view that this exception extended to misleading or deceptive conduct, conduct contrary to trade practices or fair trading legislation, tortuous conduct, and any disclosure which would prevent a party from misleading the court.2

Settlement agreements will usually also attempt to restrain disclosure of:-

(a) details of the dispute itself;

(b) any settlement reached;

(c) any criticism of the other side.

Such restraint is justified as encouraging parties to compromise, particularly where there may be similar claims in the pipeline from other claimants.

Restraining the use of information or documents is wider than restraining disclosure and may be problematic. A dispute resolution clause stated:-

“Neither party to this agreement may use any information or document obtained through the dispute resolution process established by this clause for any purpose other than in an attempt to settle the dispute.”3

Sometimes similar clauses appear in mediation agreements,4 however such restrictive words were regarded as going too far by Finkelstein J when he was considering giving approval to liquidators to enter into a mediation agreement in Sonray Capital Markets Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2010] FCA 1371 at [23].

The difficulty was the same as that identified by Rolfe J in AWA Limited v Daniels (1992, unreported: BC 9201994). A restriction against using any information gathered in the mediation process could entail a difficult enquiry as to which information came to a party in the mediation, and which information was already in the party’s mind and which may have been confirmed by something which happened in the mediation. In the Daniels case a party served on the other side a notice to produce documents which that party suspected existed, but whose existence was confirmed in the mediation. Rolfe J refused to set aside the notice to produce since it was not an attempt to circumvent the confidentiality of the mediation process.

3. By statute

Whether a statute applies, and if so which one applies, depends on which court is being asked to receive the evidence and whether the mediation was ordered by the court.

In court ordered mediations there tends to be blanket protection for anything said and admissions made in the mediation. So for example section 53B of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 provides (in respect of Federal court ordered mediations):-

Admissions made to mediators

Evidence of anything said, or of any admission made, at a conference conducted by a mediator in the course of mediating anything referred under section 53A is not admissible:

(a) in any court (whether exercising federal jurisdiction or not); or

(b) in any proceedings before a person authorised by a law of the Commonwealth or of a State or Territory, or by the consent of the parties, to hear evidence.

Where a mediation is ordered by a Queensland court, in the absence of fraud, nothing done or said or an admission made in such a mediation is admissible in court. And the mediator cannot disclose to others what happened without reasonable excuse. This is by ss 39-41 of the Magistrates Court Act 1921, ss107-109 of the District Court of Queensland Act 1967 and ss 112-114 of the Supreme Court of Queensland Act 1991. There are similar provisions for QCAT mediations.

An offer made in mediation is a thing done or said in a mediation and is therefore inadmissible even on the question of costs: Brereton J (when considering the NSW equivalent) in Azzi v Volvo Car Australia [2007] NSWSC 375. See also Underwood v Underwood [2009] QSC 107, Jones J at [38].

Mediations carried out by a Dispute Resolution Centre otherwise than upon a referral by the Supreme Court, District Court, Magistrates Court or QCAT are covered by the Dispute Resolution Centres Act 1990 (Qld). This provides5 that anything said in a DRC mediation session including any admission, is not admissible before any court tribunal or body. Documents are also protected from disclosure.

Section 131 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth)

Section 131 provides that evidence is not to be adduced (in proceedings in a Federal Court or ACT court) of:-

(a) a communication that is made between persons in dispute, or between one or more persons in dispute and a third party, in connection with an attempt to negotiate a settlement of the dispute; or

(b) a document (whether delivered or not) that has been prepared in connection with an attempt to negotiate a settlement of a dispute.

The wording closely follows the second test in Field (the connection test) and the cases referred to under the without prejudice rule (above) are relevant in this respect. However, it is notable that the section covers all communications and is not limited to admissions.

Reference should be made to the exceptions in s 131 and to the definitions in the statute. The most important exception is s 131(2)(h) which applies when “the communication or document is relevant to determining liability for costs”.

It is to be noted that there is similar wording to s 131 in the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW), the Evidence Act 2001 (TAS) and the Evidence Act 2008 (VIC). But there is no similar provision in Queensland.

Marking an offer “without prejudice” does not exclude the operation of s 131(2)(h): Ann Street Mezzanine Pty Ltd v KPMG [2011] FCA 453. W ithout prejudice negotiations carried out in a settlement conference are covered by the section: Gilberg v Maritime Super Pty Ltd (No. 2) [2009] NSWCA 394, as are mediations where there is no mediation agreement: Baulkham Hills Shire Council v Ko-veda Holiday Park Estate Limited (No 3) [2010] NSWLEC 238.

And in a somewhat bolder move, Mansfield J held that the principle extended to negotiations carried out in a mediation even where there was a mediation agreement which contained contrary provisions (Silver Fox Co v Lenard’s (No 3) [2004] FCA 1570).6

In Azzi v Volvo Car Australia [2007] NSWSC 375 at [19] and [24], Brereton J agreed with the approach of Mansfield J, but pointed out that in order for it to work, s 131 had to apply in the first place. And in a court ordered mediation, other statutory provisions applied (s 53B) and they prevailed over s 131.

In Pinot Nominees Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2009] FCA 1508 at [30], Siopis J in the context of a court ordered mediation preferred to regard s 53B as applying to the mediation and s 131 as applying to any other without prejudice negotiations between the parties.

If Silver Fox Co is right, then the current state of the law is that as far as the Federal, ACT, NSW, TAS and VIC courts are concerned, s 131 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and its equivalent in the other jurisdictions, provides a statutory framework for admissibility of communications given at, and documents prepared for, voluntarily organised mediations, even to the extent of overriding confidentiality clauses in a mediation agreement.

This means that even if a party had agreed not to do so, evidence could be given in these courts about communications made during a mediation organised voluntarily by the parties but which were not “connected with an attempt to negotiate a settlement”.

In this context we must not forget the lawyers’ professional duty not to mislead the other side in negotiations: Legal Services Commissioner v Mullins [2006] LPT 012. This has been described as a duty of candour: Legal Services Commissioner v Shera [2009] LPT 015. Cautious lawyers are expected therefore to disclose all material facts to the other side in a mediation.

The combination of the above factors has the rather unsavoury consequence that a party may regard a mediation organised voluntarily in a case before these courts as an opportunity to go fishing for facts for use at the trial even if the party has agreed not to do this.

One way to avoid this result is to insist on the mediation being ordered by the court.

It remains to be seen whether it is possible to avoid the result by opting out of the provisions of s131 in the mediation agreement.

So here finally is the table which attempts to summarise the analysis above. Please note this only applies to mediations in Queensland which do not result in settlement.

Jeremy Gordon

www.Qmediate.com.au

To access the full version click here.

Footnotes

- For example if the issue is whether or not the negotiations resulted in an agreed settlement; in certain circumstances to determine a question of costs after judgment has been given (Cutts v Head [1984] Ch. 290); and where it is evidence of an act of bankruptcy, or there was a threat if the offer was not accepted.

- Queensland Bar Association Mediator’s Conference paper 2010 pages 5 and 12.

- These words appeared in the agreement for the supply of water from the Waruma Dam on the Nogo River to the Shire of Gayndah Council under the Water Resources (Shire of Gayndah) Regulation 1994.

- In particular such a clause appears in the LEADR agreement.

- In section 36

- Although the substantive decision was reversed on appeal in Poulet Frais Pty Ltd v Silver Fox [2005] FCAFC 131, this part of the decision did not go on appeal.