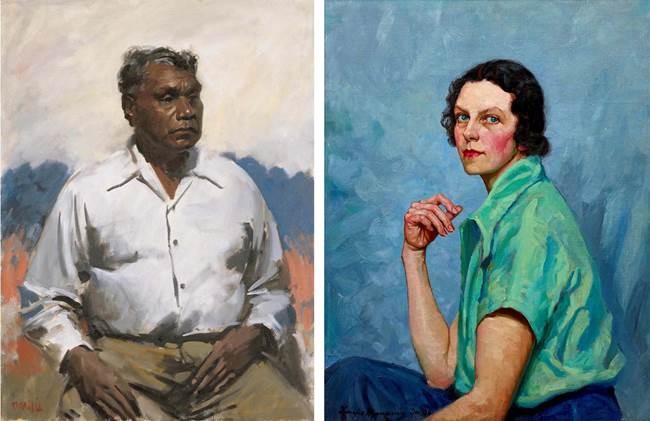

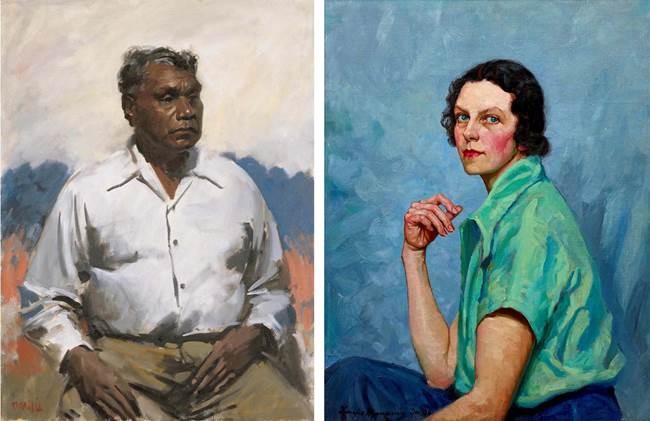

Left to right: William Dargie Portrait of Albert Namatjira 1956, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, purchased 1957 © Estate of William Dargie, photo: QAGOMA; Tempe Manning Self-portrait 1939, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Art Gallery Society of NSW 2021 © Estate of Tempe Manning

The Prize

The Archibald Prize (Prize) is the most prestigious portrait prize in Australia. Since 2015 the Prize award has been $100,000.

The Prize was first awarded in 1921, upon a trust bequest under the will of JF Archibald, former editor of the Bulletin. It is administered by the Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and is awarded for “the best portrait, preferentially of some man or woman distinguished in Art, Letters, Science or Politics, painted by an artist resident in Australia during the 12 months preceding the date fixed by the Trustees”. In addition to the selected winner, more recently there was inaugurated prizes for the “People’s Choice Award” and also the “Packing Room Prize”.

In 2021 the Prize celebrated its 100th anniversary. An exhibition of 100 artworks – Archie 100: A Century of the Archibald Prize – was curated by the Art Gallery of New South Wales and since has been travelling Australia, albeit shown (only) in regional galleries.

The exhibition is presently on show at the Home of the Arts (HOTA), at Bundall on the Gold Coast, which showing will conclude on 2 October 2023. It then moves for its final showing at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, from 20 October 2023 to 28 January 2024.

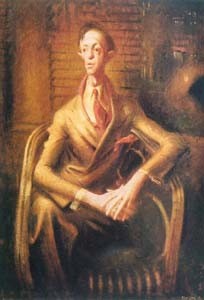

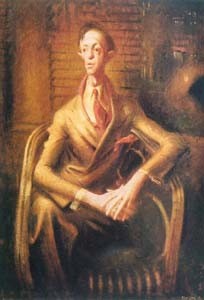

“Mr Joshua Smith” 1943

The Litigation

The Prize has not been without controversy, attracting litigation.

The most prominent of those was in 1944 concerning the 1943 winning portrait by William Dobell (later Sir William Dobell) titled “Mr Joshua Smith”, a portrait of a fellow artist. The Prize award was challenged by other artists upon an allegation it was a caricature rather than a portrait.

At the trial the claim was dismissed, but it is said that Dobell was so shattered by the challenge and the litigation, he retreated to painting landscapes.

The decision is Attorney-General (NSW) v Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales and Dobell (1944) 62 WN(NSW) 212.

In his reasons, the trial judge, Justice Ernest Roper – construing the word “portrait” as used in Archibald’s will and applying such construction – wrote (at 215):

The picture in question is characterised by some startling exaggeration and distortion clearly intended by the artist, his technique being too brilliant to admit of any other conclusion. It bears, nevertheless, a strong degree of likeness to the subject and is, I think, undoubtedly, a pictorial representation of him. I find it a fact that it is a portrait within the meaning of the words in the will and consequently the trustees did not err in admitting it to the competition.

Whether as a work of art or a portrait it is good or bad, and whether limits of good taste imposed by the relationship of artist and sitter have been exceeded, are questions which I am not called upon to decide and as the expression of my opinions upon them could serve no useful purpose I refrain from expressing them. I mention those matters, however, because I think that the witnesses for the informant, whose competency to express opinions in the realm of art is very great, were led into expressing their opinions that the work was not a portrait because they held strong views against it upon those questions. They excluded the work from portraiture, in my opinion, because they have come to regard as essential to a portrait characteristics which, on a proper analysis of their opinions, are really only essential to what they consider to be good portraiture.

Garfield Barwick KC – as the later High Court of Australia Chief Justice then was – appeared as Senior Counsel, nominally for the plaintiff Attorney-General for the State of New South Wales, but in substance for the informant challenging artists, Edwards and Wolinski. Frank Kitto KC – also later to grace the High Court – led for the defendant trustees. Dwyer KC led for Dobell.

In his 1995 memoir – “A Radical Tory – Reflections and Recollections”, 1995, at page 48 – Barwick described the case among the top three of his public failures as an advocate, the top being his unsuccessful defence of the constitutional challenge to the Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 (Cth): The Australian Communist Party v The Commonwealth (1951) 83 CLR 1.

The Exhibition

The writer attended the exhibition’s opening day at HOTA at 10.00am and was expecting – according to his usual swift passage through any art exhibition – to be away by 10.30am. So captivating was it, he stayed until midday.

The arrangement of the exhibition and the extensive narrative accompanying each artwork – artist and subject – is impressive. Dobell’s controversial portrait of Joshua Smith is not part of the exhibition but included is the 1944 Archibald Prize winning portrait by Smith himself, of the politician, JS Rosevear. Brett Whiteley‘s 1978 Prize winning work “Art, Life and the other thing” – also on show – comprises a stunning self-portrait of Whiteley holding a copy of Dobell’s “Joshua Smith”. Whiteley’s work is far more a caricature than Dobell’s work, no doubt reflecting modern art mores.

This exhibition is not to be missed.

The writer attended on a Saturday. It is advisable to book online but HOTA regulates entry to avoid over-crowding. Complimentary carparking for 3 hours is available but remember to enter your vehicle details in the parking machine nonetheless or you risk a fine.

The HOTA complex itself is an architecturally interesting building. It harbours different precincts which add to the emerging arts and cultural scene on the Gold Coast. In addition, Palette Restaurant, The Exhibitionist Bar and HOTA Café are excellent dining options. The viewing area on the top floor – providing expansive views of the Gold Coast coastal skyline to the north and east – is worth enjoying while attending.

Links and Further Reading

The Art Gallery of New South Wales link to the touring exhibition – including links to the artwork on show – may be found here: https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/whats-on/touring-exhibitions/archie-100-tour/

For further reading on the 1944 litigation see Peter Edwell “The Case that Stopped a Nation”, 2021, Halstead Press.

As to another unsuccessful challenge, namely to the 2004 Prize winner – and applying Justice Roper’s 1944 reasoning – see Johansen v Art Gallery of NSW Trust [2006] NSWSC 577 per Hamilton J: https://www.caselaw.nsw.gov.au/decision/549fcf8e3004262463bdbb8c

Left to right: William Dargie Portrait of Albert Namatjira 1956, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, purchased 1957 © Estate of William Dargie, photo: QAGOMA; Tempe Manning Self-portrait 1939, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Art Gallery Society of NSW 2021 © Estate of Tempe Manning

Left to right: William Dargie Portrait of Albert Namatjira 1956, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, purchased 1957 © Estate of William Dargie, photo: QAGOMA; Tempe Manning Self-portrait 1939, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Art Gallery Society of NSW 2021 © Estate of Tempe Manning

“Mr Joshua Smith” 1943

“Mr Joshua Smith” 1943