Author: Mark FowlerPublisher: Shepherd Street PressReviewer: The Honourable Patrick Keane AC KC

This review was delivered by the Honourable Patrick Keane AC KC on the October 2024 launch of ‘Beauty and the Law’ at events organized by the Australian Christian Legal Society at the Banco Courts in Sydney and Melbourne.

At the very beginning of the Christian era the apologist Tertullian posed the rhetorical question ‘what has Athens to do with Jerusalem?’ In Beauty and the Law Dr Fowler demonstrates that the answer is, well, quite a lot actually.

In this very accessible collection of lectures Dr Fowler reminds us that within both the classical tradition of Greece and Rome and the Judeo-Christian tradition, there are persistent affirmations of the psychocultural relationship between the true, the good, the beautiful and the just. Aristotle, for example, in what was for him a rare moment of poetic indulgence, famously wrote ‘great is truth, and more beautiful than the morning star’.

While reminding us of these common themes in these great intellectual traditions, Dr Fowler mounts a compelling case against the pessimism of post-modernist critical theory. By this I mean the worthy pretence that human beings are without hope; the notion that it is an illusion to think that there can be common ground between human beings as to what is true or good or beautiful or just; and the associated and hopeless notion that passive victimhood is the essential and perhaps the only real political virtue.

Closer to home, so far as this audience is concerned, within the tradition of the common law, the relationship between truth and justice and beauty are almost axiomatic. Dr Fowler’s lectures are prompts to sensitize us, time-poor, practice-focussed lawyers, to the real relationship between the just and the beautiful and the true. In that regard even we, harassed, time-poor, practicing lawyers, can appreciate, if we are sufficiently alert to it, the force of his insights in our daily lives and our daily practice.

Judge Learned Hand, the greatest American judge of the 20th century had occasion over a very long judicial career to reflect upon what made work as a judge worthwhile, it being obvious that no one would do it for the money. There is real beauty in the forceful elegance of Learned Hand’s judgments, even a hundred years on. Learned Hand’s considered opinion was that the great reward, and indeed the only real personal reward of judicial office, is the aesthetic satisfaction to be derived from devising the fittest legal solution to the problems of human conflict; the problems that are presented to the courts.

In this regard, Learned Hand was acknowledging the deep joy that human beings derive from solving, and solving well, the problems thrown up by our environment, including especially the problems involving disputation and disruption in our social relationships. Importantly, we’re not speaking here of the desire to prevail as a party in any of those conflicts. We’re not speaking of a Nietzschean will-to-power in contest with others. The insistence of the common law tradition on judicial independence and impartiality is entirely inconsistent with such an ideal.

The psychological and cultural power of the great tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides remain of universal appeal because those plays engendered what Aristotle referred to as ‘pity and terror’. All of us can see the situations presented in those tragedies are tragic. They are tragic because they were apparently unavoidable. But they are also tragic precisely because they should have been avoidable.

As in the Oresteia of Aeschylus, it’s the gift of the jury that enables us to resolve those tragic problems. It’s the gift of our legal system that enables us, all of us, to see the true occasions of justice. Human tragedy should be avoidable. That’s our job. And we humans, in virtue of our common humanity, are capable of seeing that and of acting accordingly.

And so, I commend Mark Fowler’s book to you as an aid, as a prompt, to meditation upon these very large themes that are immanent in our daily lives and work as lawyers, however mundane that work might sometimes seem. These lectures worthily champion the essential, hopeful view that we, all of us, can know an injustice when we see it, even if we have not been its victim. I commend Beauty and the Law to you and I’m delighted to declare this book launched.

Address to the Queensland Bar Practice Course in Brisbane on 28 May 2015 by the Honourable Patrick Keane AC KC.

Good Barristers; Bad Days

In Memoriam, the Honourable Patrick Keane AC KC presented the inaugural Bruce McPherson CBE Memorial Lecture on ‘Christian Inspiration and Constitutional Insights‘ on 21 March 2024 at the Banco Court, Supreme Court Brisbane, QEII Courts of Law.

Dedication

In an address to honour the memory of Bruce Harvey McPherson, it is entirely appropriate to speak of inspiration. For all those who had the great good fortune to benefit from McPherson’s deep learning, his wit and wisdom, and above all, his dedication to the doing of justice according to law, Bruce McPherson was truly an inspiration. Many lawyers of my generation who heard McPherson QC argue a case in court, or who read the learned, insightful, and beautifully expressed judgments of McPherson J, tried to emulate him, especially those of us who had the privilege of working with him at the Bar or on the Bench.

Bruce McPherson was the most erudite lawyer in Queensland; and amongst Australian lawyers, only he could have written a book of the depth and breadth of his classic text on company liquidation. After serving for ten years as a Justice of the Supreme Court, he was a foundation member of the Queensland Court of Appeal established in 1991. His judgments did much to establish that Court’s reputation as one of the strongest courts in the common law world.

Bruce McPherson’s great legacy to those he inspired was his insistence that our courts should seek to do justice according to law. This did not mean that the law should not change: McPherson was a great law reformer. As a member and later leader of Queensland’s Law Reform Commission, the Trusts Act and the Property Law Act are abiding reminders of his success as a law reformer. He was deeply concerned that justice should be done under laws that were kept fit for purpose, but he was equally concerned with how changes in the law that should be achieved. The great contemporary contrast with his view was that of Lord Denning.

For McPherson, the cardinal judicial virtue was not a passionate commitment to doing what one finds personally agreeable, but fidelity to the rule of law.

Lord Denning was known for his passion for justice; to the extent of not letting the law get in the way of justice as he saw it. Lord Denning was greatly influenced by William Temple, the Archbishop of Canterbury, whom he described as “one of the greatest thinkers of the [20th] century.”[1] In Denning’s book The Road to Justice[2] he described how taken he had been with an address by Archbishop Temple to the Inns of Court Temple began with the words:

“I cannot say that I know much about the law, having been far more interested in justice.”

Temple’s observation was quite amusing; but there was, in its cavalier insouciance, an encouragement to those judges who find the law less merciful or generous than they think it should be to use their office to something about that. Denning was very much Temple’s disciple. McPherson, in contrast, was sceptical of judges who were disposed to regard their instinct for justice however passionate, as a surer guide to a just decision than the law of the land.

For McPherson, the cardinal judicial virtue was not a passionate commitment to doing what one finds personally agreeable, but fidelity to the rule of law.

McPherson insisted that the rule of law binds the judges as firmly as it binds the people and the other branches of government and the people. Just as legislative and executive power are limited, there are limits to the scope of judicial competence, Judges should not, under the guise of deciding what the law is, determine what the law should be where that involves usurping the authority of the people’s representatives to decide political questions of the kind that divide political parties. He was firmly of the view that justice is not a matter of judicial benevolence or of second guessing the legislative efforts of the elected representatives of the people. Bruce did not approve of the jurisprudence of the warm inner glow.

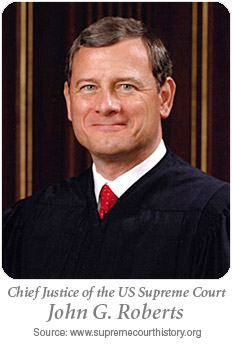

Doing justice according to law can be hard on people who feel that they are entitled to more from their fellow citizens. It can also be personally unsatisfying to the judge. But the wisdom of McPherson’s modest view of the proper scope of judicial power is apparent in the convulsions wrought in the United States by popular outrage on all sides of politics, against decisions on political questions by a judiciary that is seen to act as a super-legislature. To this point I will return at the conclusion of my remarks.

Introduction

It is a lament familiar in much contemporary discourse that, in liberal democracies of the West, Christian values and Christian institutions are waning in strength and influence to the detriment of their communities. Whatever merit there may be in these laments, they are, it seems to me, missing a bigger picture. We should be mindful of, and appreciate, the extent to which the constitutional arrangements of the liberal democracies in Australia and the United States actually embody an understanding of the relationship between the private individual and the community and its public institutions that is distinctly Christian in its inspiration. The civic life of our democracies is conducted within, and shaped by, this framework; and that remains the case whatever the level of Church attendance.

Our modern liberal democracies are, of course, multi-faith and multicultural communities. Church attendances may be in decline, and the influence in our public life of Church hierarchies and organisations may have declined over the last fifty years. But, if one considers the big picture one can see in the constitutional arrangements of Australia, and our cultural lode star, the USA, that central aspects of the Christian message have been absorbed and implemented in ways that permanently differentiate our liberal democracies from the alternatives, whether they be democratic, autocratic, or theocratic.

We should be mindful of, and appreciate, the extent to which the constitutional arrangements of the liberal democracies in Australia and the United States actually embody an understanding of the relationship between the private individual and the community and its public institutions that is distinctly Christian in its inspiration.

Before going further, I must acknowledge that crucial elements of the Christian message about which I wish to speak reflect ideas associated with school of Hillel as part of the rich intellectual heritage of the Jewish people. I also acknowledge that, as a matter of history, the absorption of which I speak was neither linear nor smooth: ambiguities in, and inconsistencies between, aspects of Christian thought roiled the lives of Christian peoples, and of their unfortunate neighbours, for nearly two millennia. Atrocities committed in the name of Christianity have shamed humanity with violence, bloodshed, intolerance, and greed. All that said, it remains true to say that, in the history of ideas, while the classical models of democratic Athens and republican Rome provided the basic ideas for the political architecture of democratic government in the West, the “liberal” element of liberal democracy embodies a distinctly Christian understanding of the relationship between the individual and the State, between the private and the public lives of its citizens.

The United States and Australia are characterised as liberal democracies, because their constitutions establish a system of government that postulates the individual as the basic moral unit of society, and the equal dignity of each individual without regard for difference in wealth or social position. The State’s legitimate role in the private life of the individual is limited by these postulates. This understanding finds its characteristic expression in constitutional provision for limited government, and the maintenance of these limits by the separation of governmental power between the legislative, executive and judicial organs of government.

Over the centuries Christian communities endured absolute monarchy and, in medieval times, tendencies to theocracy. That experience would eventually lead, with Christian inspiration, to the embrace of the notion that only the people themselves, recognising the equal voice, could be relied upon as the guarantor of the limits on the power of the State.

Paul and Augustine

Democracy as rule by the people originated, as the word itself suggests, from classical Greece – and Athens in particular. But the Athenian conception of democracy was very narrowly based. It also exhibited a strong totalitarian tendency. So did the civic life of the Roman Republic and Empire. In these models of government, there was little recognition of the private life of the individual. People, even those who consoled themselves with Stoic resolve, lived their lives in public. The value of their lives depended upon the accretion of wealth and social status. The closest synonym to the Latin word dignitas was “reputation” or “honour”. The dignitas of Julius Caesar was entirely a matter of his aristocratic lineage and the honours he won: and it completed by in his posthumous public recognition as a god.

Christianity was, from its earliest moments of self-consciousness, concerned with the salvation of the individual, as a creature of inherent value, beloved by God as if there were nothing else; this without regard for differences of wealth or social status. And once Paul emerged victorious in his contest with the more inward looking Jerusalem-based followers of Jesus, the Christian message became a mission to all humankind.

The foundational ideas that pursuit of his or her salvation is the destiny of each individual and that each individual is of equal value in that regard, derive, not from any classical Greek or Roman model, or indeed from any other branch of Western philosophy (save, as I have said, for the school of Jewish thought associated with Hillel). They are a peculiarly Christian message.

Christianity was, from its earliest moments of self-consciousness, concerned with the salvation of the individual, as a creature of inherent value, beloved by God as if there were nothing else; this without regard for differences of wealth or social status.

Over two thousand years, Christians regularly went to war with each other over what fidelity to the Christian message required of them. The writings of St Augustine of Hippo were the source of much of what was inspiring in the Christian message. They were also the source of much of the contention. It was no coincidence that Martin Luther was an Augustinian priest.

Apart from Paul, Augustine was the most important of the early Christian thinkers. His great self-revelatory work, The Confessions, became for the next fifteen hundred years, the most influential book in Christendom apart from the Bible itself. In it Augustine eloquently affirmed the central importance of the personal relationship between God and the individual. And when Augustine spoke of his Church as “Catholic” he was reaffirming Paul’s view of the universality of the Christian mission.

Yet, for St Augustine, we humans are so deeply flawed by the tendency to evil associated with original sin that we cannot hope to find our way to salvation outside the teachings of the Church. While the pursuit of salvation centred on an intensely personal relationship between each human soul and God, imperfect humans needed the help of Christ’s church to establish and maintain the connection. Augustine’s view was that, as a matter of love, an erring soul should be compelled, by force if necessary, to adhere to the Church’s teachings. Once Christianity allied itself with the Roman Imperial State and its successors in Europe, the tension between these aspects of Augustine’s thought became, for a long time after the decline of Roman rule in the West, a matter of life and death for Christians; and, unfortunately as well, for those with whom Christians came into contact.

Liberty

Augustine, in De Civitate Dei, Book XIX, said:

“[B]y nature, as God first created us, no one is the slave either of man or of sin.”

In the history of ideas, and in the fullness of time, the noblest contribution of Christianity to the history of the world, was its part in the abolition of slavery and the slave trade.

Of course, liberty was important to the ancient Greeks and Romans. In the republican Rome of Cicero, the idea of liberty was valued so highly that the preservation of liberty could be invoked as a complete justification of the assassination of the Republic’s leading citizen. But this was a special kind of liberty; it was not a notion of freedom from subordination to others. Nor was it a universal entitlement; it had nothing at all to do with ordinary people. Rather, it was a matter of social status within the community that allowed the superior man to achieve honour and reputation by participating in the government of that community. And, I say “man” advisedly.

In the brilliant societies of classical Greece and Republican Rome, almost no one was simply free. All but the aristocratic elite were subject to a tangle of personal constraints that were fixed by one’s social status which was almost invariably a function of wealth. Most importantly, classical Greece and Rome were slave societies. Classical Greece and Rome could not have functioned without the enslavement of a large segment of the population. This most brutal form of subordination of the weak by the strong was essential to the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome.

Slavery had been part of the human condition from before the time that humans began to keep historical records. The Greeks and Romans regarded slavery as the natural state of affairs; their philosophers did not suggest otherwise. For Aristotle, it was obvious that enslaved people were born, to be slaves. Slavery as an institution reached an apogee of sorts under Imperial Rome. People enslaved by the Romans were put to work at the oars of their ships, and in their mines, and on their huge farms, to maintain Roman wealth and power. These enslaved people were worked to death in enormous numbers. People kept as domestic slaves by the Romans were regarded as chattels who were routinely subjected to the sexual demands of their owners. Within classical Roman culture, the rape of enslaved people by Roman masters was actually celebrated, as we know from the frescoes which cheerfully adorned the villas of the Roman aristocracy.

As St Augustine explained in De Civitate Dei[3], God, in creating man with dominion over nature “did not intend that His rational creature, who was made in His image, have dominion over anything but the irrational creation – not man over man …”

Central to Augustine’s thought were the ideas that God loves each and every one of us as if there were no one else; and the idea that each of us shares the tendency to evil associated with the idea of original sin. When Abraham Lincoln famously declared in the course of the Peoria debate with Stephen Douglas in 1854, that “no man is good enough to rule over another man without that other’s consent,” that insight resonated powerfully with his audience because they shared the belief that every individual has his or her personal moral destiny, and, that humans are too imperfect to presume to take responsibility for the moral destiny of another.

The great liberating idea at the root of the Christian message was:

“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbour as yourself”. Luke 10:25-27

In the New Testament, as in the Old, slavery is referred to as an entirely unremarkable institution. For most of the long centuries after Augustine, Christians continually proved themselves to be no less as enthusiastic in the enslavement of their fellow humans than anyone else, especially when it came to the conquest and settlement of what they were pleased to call the “New World”. It took a long time for the message that no Christian could, in conscience, allow the enslavement of another individual equally beloved by God to be achieve sufficient resonance to become the basis for a political program of abolition. But when it did, it was not the classical thinkers like Aristotle or Cicero, or natural law theorists, or “philosophes” of the Enlightenment whose ideas marshalled the forces that ended the slave trade and slavery in Western Europe and the United States. It was the recognition by the mass of politically articulate Christians that to hold another human being in bondage was simply inconsistent with the Christian obligation to do unto others as we would have them do unto us. As a matter of historical fact, it was the Christian message, championed by remarkable people like William Wilberforce, that led to the political agitation which led to the abolition of the slave trade after the Napoleonic Wars, of slavery in Europe. The cause of Abolition in the United States was a Christian endeavour nonetheless because the people on the other side were also Christian.

The abolition of slavery was not a manifestation of some coherent and comprehensive project of universal human rights to be enforced by the civil power. Christ’s Kingdom was emphatically not of this world. The inspiration was that to hold another human in bondage was, when one thought about it, evidently and emphatically inconsistent with loving one’s neighbour. And one’s neighbour is, as the parable of the Good Samaritan shows, any other person who comes within one’s power to help or harm.

In the history of ideas, and in the fullness of time, the noblest contribution of Christianity to the history of the world, was its part in the abolition of slavery and the slave trade.

It might fairly be said that Christians took a long time thinking about this. But the time did come when enough of them felt duty-bound to do something about it; and when they did, the influence of Augustine’s thought was apparent. By 1776, Thomas Paine had a wide, receptive, and almost entirely Christian audience for his “plain truth” that “all men being originally equals”, and that being so, it was simply absurd to suggest that God had granted to any person, or that person’s heirs, the right to rule over others, whether as slaves or subjects.[4] Montesquieu, to whom the American Founders looked for guidance, observed, in a famous piece of sarcasm, that “enslaved Africans could not possibly be human beings because if they were, it would follow that we ourselves are not Christians.”[5]

Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and the other authors of the Declaration of Independence proclaimed that it was self-evident that all men had been created equal and enjoyed, by virtue solely of being so created, an inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Note here, that the trio of inalienable rights was not John Locke’s “life, liberty and property: the “pursuit of happiness” was apt to comprehend the moral destiny of the individual’s pursuit of her or his moral destiny.

The Declaration of Independence asserted that these truths were “self-evident.” But that was simply not so: “these truths” would have been regarded as arrant nonsense by Aristotle and Plato and Cicero and Caesar and Constantine, by the barons who forced King John to sign Magna Carta, and, frankly, by the vast majority of the white populations of the southern colonies in North America.

One might pause here to observe that there is at least a serious question as to the historical accuracy of the assertion by those who propounded the US Constitution that they were truly united as “We the People”. There were deep differences between the hardy self-reliant Puritans of the New England colonies and the slave-owning aristocracies of the South. In this regard, before the Convention which proposed the Constitution for adoption by the American people, George Washington had written: “We are either a United People or we are not. If the former, let us, in all matters of general concern, act as a nation … If we are not, let us no longer act a farce by pretending to it.” His more clear-eyed fellow Virginian, James Madison, saw things differently. Madison saw the division between the colonies by reason of “their having or not having slaves” as a lethal threat to the unity of the new nation.[6] Time would prove that Madison had the right of it.

I would suggest that the confident assertion in the Declaration of Independence that “these truths” were self-evident, i.e. as a matter of natural reason, was calculated deliberately to mask the essentially Christian origin of the propositions it espoused. In Thomas Jefferson’s original draft of the Declaration of Independence, he had written: “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable …” When Jefferson showed his draft to Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, they suggested the crucial alteration from “sacred and undeniable” to “self-evident”. This self-conscious expedient to avoid any suggestion of an appeal to a religious foundation for these rights reflected a wariness of the debilitating divisions of Christian sectarianism.[7] In this spirit, Thomas Jefferson had earlier claimed:

“our civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions any more than our opinions in physics or geometry.”[8]

Later, in 1797, John Adams, as President, would assert with a straight face that “the Government of the United States is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”[9]

While the subtle editorial change in the Declaration expressly to appeal to “natural reason” helped to sustain the appearance of religious neutrality on the part of the Founders, the source of the inspiration for the Declaration’s was the same for Jefferson, Franklin and Adams as it had been for John Locke whose followers they were. John Locke would write in his Second Treatise of Government, that all men were born into a state of “equality, wherein all the power and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another”, each “equal to the greatest, and subject to no body”.[10] Locke too, may have appealed to natural law and reason, but it was the echoes of Augustine that resonated with his readers.

The truth about the Christian source of the Declaration’s inspiration might have been masked; but it could not be denied. In the 1858 debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas on the question whether negroes in the United States were as entitled to the same benefit of the rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence as any white person, Lincoln referred to the fact that Thomas Jefferson was a slave owner but reminded his audience that Jefferson had said on the subject of slavery that “he trembled for his country when he remembered that God was just.”[11]

Separating Church and State: Public and Private

“Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” Matthew 22, 22

The message of Matthew 22 is not only that the State has no legitimate claim upon the religious life of the individual but also that the public life of an individual should be kept separate from his private religious convictions. That is the message that John Kennedy invoked in 1960 when he famously explained to sceptical Protestant voters that he was not the nominee of the Catholic Church for President of the United States, but rather the nominee of the Democratic Party who happened to be a Catholic.

I suggest that the adoption by the United States in 1791 of the First Amendment’s prohibition of governmental preference for one form of religious observance over another as a condition of participation in the governance of the Republic was in no way a repudiation of Christianity as the religion of the vast majority of Americans; rather it was an affirmation of basic Christian values reflected in Matthew 22. The same may be said of S116 of our Constitution which relevantly followed the First Amendment in this respect.

In the State religions of classical Greece and Rome, the purpose of religious observance was a matter of public concern, to placate the gods to keep the city safe and prosperous. The same had been true of the more ancient cities of the Near East since the birth of civilisation. The primary concern of Christianity on the other hand was the salvation of the individual independently of the life of the city or the Empire. St Augustine famously asked rhetorically: “What does it matter to a dying man under what form of government he lives so long as it does not compel him to sin or to give him scandal.” Of course, experience would later show that, if the government demands obedience by a dying man to a particular view of religion on pain of death at the hands of the government, the answer to Augustine’s rhetorical question is that it matters a lot.

In the closely associated lives of the populations of the cities of classical Greece and Rome, everyone knew everyone else’s business. And as the proper worship of the gods was thought to be essential to the public welfare, there was little room for the notion that there could be things that belong to the gods that were not also of vital concern to the community and the responsible authorities. It was in this very context that the charge of blasphemy was brought against Socrates. It was also this mindset that prompted the testing of Jesus by the Pharisees tested Jesus which elicited the radical proposition in Matthew 22.

Socrates did not seek to defend himself against the charge of despising the gods by asserting his right as an individual to his own opinion about the gods and what they required of him. Such an assertion would have made no sense to him, or to his fellow citizens, or to the citizens of classical Rome. They were all dependent socially and indeed psychologically upon the communal life of their city. Plato tells us in the Apology that Socrates refused the opportunity to escape into exile because, as a child of his city’s laws as he described himself, he could not imagine the possibility of a worthwhile life outside them. And equally for the Pharisees who tested Jesus, the notion of a moral choice by an individual independent of the approval of their community made no sense.

The political philosophy that Plato developed in his reaction to what he saw as rule by the mob he despised did not include any notion of a private life of one’s own. His philosophy was one of totalitarian aristocracy; rule by grim guardians who would decide comprehensively what is best for the rest of us, whether we liked it or not, in every aspect of our lives. In Plato’s cheerless republic, there was no place for poets.

The limits to the legitimate authority of the State over matters of private belief were illustrated by the author we know as St Luke in Acts 18: 12-16. While St Paul was living and teaching in Corinth:

“When Gallio was proconsul of Achaia, the Jews with one accord rose up against Paul and brought him to the judgment seat, saying,

‘This fellow persuades men to worship God contrary to the law.’

And when Paul was about to open his mouth, Gallio said to the Jews,

‘If it were a matter of wrongdoing or wicked crimes, O Jews, there would be reason why I should bear with you. But if it is a question of words and names and your own law, look to it yourselves; for I do not want to be a judge of such matters.’

And he drove them from the judgment seat.“

In the bilious anti-Semitism of the inveterately pro-Roman author of Luke we have one of the earliest statements of the insight which, eighteen centuries later, would come to prevail as an axiom of liberal democracy. That is, that the private religious beliefs of citizens are of no legitimate interest to the State.

While the attitude on the part of the Roman Imperial state expressed by Gallio was no doubt welcomed at the time by Christians as members of what was then a small and often persecuted sect, it would prove to be otherwise after Christianity was established as the State religion of the Empire. Scant attention was paid to Matthew 22 while the power of the Church was ascendant in the world as an institution enjoying State sponsorship. The temptation to deploy the power of the State to crush the perceived enemies of the true faith would prove irresistible.

In the 4th Century AD, Constantine took the Church into alliance with the State to bolster the legitimacy of imperial rule; and in 381AD the Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. These world-changing acts of political expediency meant that the idea that the private or inner life of the individual was a realm separate from the public life of the governed would be muddled or ignored for more than a millennium. Countless lives would be lost in civil strife over religious beliefs. But the force of the idea that there was a separation between the public and the private that required that religious belief should not be coerced by the State never disappeared entirely from the Christian conscience.

In the late 8th Century, the English monk, Alcuin of York, Charlemagne’s chancellor, objected to his master’s attempt to force the conversion of the Saxon tribes to Christianity by fire and sword. Alcuin said: “Faith arises from will not from compulsion.”[12] He was speaking of the individual will of each convert who had to be allowed to make up his or her own mind. Alcuin went on to say:

“Let peoples newly brought to Christ be nourished in a mild manner, as infants are given milk – for instruct them brutally, and the risk then, their minds being weak, is that they will vomit everything up.”[13]

Marsilius of Padua, writing in the 14th Century, observed:

“That no one is commanded in evangelical scripture to be compelled to observe the commands of divine law by temporal penalty or punishment.”[14]

The tensions generated by the claim of the individual to pursue her or his own salvation and the institutional claim of the Church that there is no salvation outside its discipline were both creative and destructive. The alliance between the Church as an institution and the nascent European States that emerged from the remains of the Roman Empire helped to generate and direct the energies that produced the glories of medieval art and architecture. In medieval Europe, armies of people in religious orders bound by vows of poverty, chastity and obedience cleared forests, raised flocks, tended vines, and traded in wool and wine and books. They built hospitals to care for the sick and the needy. They also educated Europe’s children, staffing its schools and its glorious universities. Thus, they made education available beyond the ranks of the aristocracy and thereby doomed aristocracy as the dominant social class. They were the indispensable instrument in the recivilising of Europe, and making it prosperous. They exemplified much of what was best in humanity.

In the bilious anti-Semitism of the inveterately pro-Roman author of Luke we have one of the earliest statements of the insight which, eighteen centuries later, would come to prevail as an axiom of liberal democracy. That is, that the private religious beliefs of citizens are of no legitimate interest to the State.

On the other hand, and tragically, the horrors of the Inquisition and of the wars of religion were also provoked and justified by a zeal that was itself peculiarly Christian. The Inquisition holds a particular fascination for the modern mind. To us, it is obvious that to burn a person who happens to disagree with you on a matter of religious belief is not to uphold a principle of good government; it is simply to burn a person.

The horrors of the Inquisition were driven by the willingness of the Dominicans who made up its staff to act upon the mandate St Augustine drew from words used in the parable of the banquet recorded in Luke 14.15-24, “compel them to come in so that my house may be filled”. On this view, if one loves one’s neighbour, one does not allow him or her to go freely on his or her own way in error, because that way lies eternal perdition. And so love requires that the erring soul be brought back, by force if necessary, to the true path within the Church’s teaching. And, unfortunately for large numbers of people in southern Europe during the high Middle Ages, the Dominicans loved them very much. The Inquisition reminds us that atrocities that we might ordinarily expect to be committed by deranged and blood-thirsty tyrants can also be committed by earnest and well-meaning bureaucracies.

In Europe, after the Reformation, the claims of religion were still ruthlessly enforced by the State, and so remained a source of misery for Europe’s people. Thomas Hobbes, the most sober thinker in England at the time of the First Civil War, identified the disruption and cruelty of that war as having been caused by “nothing other than the quarrelling about theological issues.”[15]

The beauty of the Christian insistence upon the separation of Church and State was not grasped by the politically articulate in Europe until the catharsis of the Thirty Years War in the 17th Century and the exhaustion of sectarian zeal that followed the bloodshed. In the 18th Century, the seed in Matthew 22 fell on fertile ground by then well manured with the blood of Christians. At that time, Frederick the Great of Prussia spoke for a broad Christian consensus in Europe when he said that “everyone must be allowed to go to heaven in his own way”[16].

Once this is accepted it is easy to speak of the individual’s pursuit of salvation as the pursuit of happiness. While this understanding of the Christian message in Matthew 22 may have been a long time coming, the necessity for the separation of Church and State was embraced as an essential feature of our constitutional law in the First Amendment of the US Constitution and in s 116 of our Constitution.[17]

Importantly in this regard, John Locke, in A Letter Concerning Toleration published in 1689 proceeded from the postulate that the individual is the fundamental moral unit of society to reason that because individuals entered into social relations with others to ensure their physical security, the social contract between individuals in no way impinged on an individual’s freedom to worship according to his or her own lights. Locke said:

“The care of souls is not committed to the civil magistrate any more than to any other man … [because] his power consists only in outward force, but true and saving religion consists in the inward persuasion of the mind, without which nothing can be acceptable to God.”[18]

In contrast to the classical view of the Greeks and Romans that the community was the basic moral unit, Locke’s focus on the “inward persuasion of the mind” of the individual believer resonated particularly with his Protestant readers because it was a central element of their common experience of their Christian faith.

Ironically, and as an example of the contingent nature of the flourishing of the Christian seed in Matthew 22, while the Americans were adopting the First Amendment, Revolutionary France was nationalising the Catholic Church, and embarking upon the Terror.

For Robespierre and the Jacobins, the Terror was the instrument of the virtuous wielded in the name of the General Will to ensure that the governed, who could not be trusted to know what was truly good for them, would be forced to be free.

Robespierre was, notwithstanding his Jesuit education, a disciple of the distinctly un-Christian Jean Jacques Rousseau, one of the most awful people ever to have told other people how to live their lives. Rousseau’s theory was that men are inherently good by nature and that human happiness would blossom if only the chains of corrupt social institutions could be removed. If men were set free of bad laws by the rule of the virtuous who alone truly grasped the General Will, then everyone would enjoy the rights with which they had been endowed by nature and which were now being proclaimed by the virtuous revolutionaries. Robespierre said:

“The Declaration of Rights is the Constitution of all peoples, all other laws being variable by nature, and subordinated to this one.”[19]

In this spirt of sunny optimism, the Revolution proceeded to eat its children.

Limited Government

If one takes seriously the notion that an individual may owe different and separate obligations to Caesar and to God, it must follow that the claims upon us of those who claim to speak for God or Caesar are to be limited to their proper spheres of authority. That necessarily raises questions as to the drawing of boundaries between what is owed to Caesar and what is owed to God. The drawing of these boundaries posed momentous challenges. Matthew 22 created a focus for contention but did not designate an arbiter to resolve the question. The experience of divinely appointed monarchs, whether in alliance with or opposition to church bureaucracies, proved to be disastrous disappointments.

If one takes seriously the notion that an individual may owe different and separate obligations to Caesar and to God, it must follow that the claims upon us of those who claim to speak for God or Caesar are to be limited to their proper spheres of authority.

As the issues created by the propositions in Matthew 22 were characteristically Christian, so ultimately, was the solution. Ultimately, the Christian communities of the West would repudiate both Constantine’s takeover of Christianity, and attempts at reverse takeover of the State by the Medieval Church in favour of a constitutionalism that would recognise the power of people of each community to exercise ultimate control of the limits upon government.

Limited Government, and Equal Dignity

“There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Galatians 3:23

Aristotle in Politics III, Chapter 6 accepted that the authority of all the citizens is the ultimate check on the political power of the government of the State, but his view of citizenship was very narrow. In Politics III, Chapters 1, 3 and 7 he described a citizen as one who participated in civic government excluding women, boys, foreigners and slaves. But for Thomas Aquinas, those excluded from citizenship by Aristotle were indeed “citizens in a certain sense”.[20] And after Aquinas, Marsilius of Padua, writing in the early 14th Century, would declare: “That only the universal body of the citizens or its prevailing part is the human legislator …” and that “only the legislator or someone else by its authority can give a dispensation from human laws.”[21]

As a matter of historical fact, the practical success of this element of the Christian message was, of course, highly contingent on circumstances of time and place. One illustration of this point that would have appealed to Bruce McPherson involves a comparison between Magna Carta and the Declaration of Arbroath.

Despite the involvement of Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury, in the drafting of Magna Carta there was little evidence of Christian inspiration in the instrument itself. It was, in large part, calculated to preserve the feudal privileges of a tiny fraction of the population, the Norman barons, against encroachment by the Angevin kings.

If we take, for example, the famous promise in cl 39 that “no free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor will we go against him, nor will we send against him, save by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land“, we can see that this promise offered no comfort to the unfree people, i.e. the villeins, who made up at least half, and perhaps even four‑fifths, of the population[22]. The Norman barons remained free to treat their villeins, who were Englishmen, as they pleased.

In cl 40, the King famously promised: “To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay, right or justice.” This did not help the villeins, or indeed even free men, in the courts of the barons: it afforded no protection against the arbitrary power of the barons who held their own courts and administered their own justice in them.

In any event, Magna Carta had little real effect in the development of constitutionalism. In an address to the Friends of the British Library, Jonathon Sumption observed that, before Sir Edward Coke in the 17th Century, English ideas of limited government owed more to Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas than to Magna Carta. It was Coke who developed a myth of Magna Carta as an original expression of the special English genius for constitutional government. Lord Sumption made the telling point that in Shakespeare’s play “King John”, there is not even a mention of Magna Carta or of the incident at Runnymede in June 1215.

In any event, Magna Carta had little real effect in the development of constitutionalism. In an address to the Friends of the British Library, Jonathon Sumption observed that, before Sir Edward Coke in the 17th Century, English ideas of limited government owed more to Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas than to Magna Carta.

An instrument which was much more significant as a marker of the development of the constitutionalism in that it explicitly asserted the voice of the people as the ultimate limit on government was the Scottish declaration of independence, formally known as the Declaration of Arbroath, of 1320. The Declaration was a letter to the Pope urging his Holiness to lift the interdict on Scotland which Edward II of England had procured from Rome after the great Scots victory under Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn. The interdict was intended to restore Scotland to the dominion of the English King. Scottish churchmen, in particular Bernard, the Abbott of Arbroath wrote the Declaration in terms that were explicitly Christian in their inspiration. The text expressly adopted and adapted the passage from Galatians: “There is neither weighing nor distinction of Jew and Greek, Scotsman or Englishman.”

The Declaration said of King Robert that:

“Him, too, divine providence, his right of succession according to our laws and customs which we shall maintain to the death, and the due consent and assent of us all have made our Prince and King …

By him, come what may, we mean to stand.“

The Declaration went on:

“Yet if he should give up what he has begun, and agree to make us or our kingdom subject to the King of England or the English, we should exert ourselves at once to drive him out as our enemy and a subverter of his own rights and ours, and make some other man who was well able to defend us our King; for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.“

This was an explicit statement that the authority of the King came, not as God’s anointed, but from the people he ruled, and what the people had given, they could take back. The Declaration thus ” proclaimed a doctrine that the king ruled by consent of the ruled.”[23]

And it did so in terms that enable one to understand why Bruce McPherson was so proud of his Scottish heritage; and why the rest of us can be proud to be human beings.

John Locke would complete his great work of political philosophy Two Treatises of Government, during the period of extreme political tension that resulted in the expulsion of James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The dangers were such that Locke kept his great work secret for a long time, referring to it when communicating to his friends as De Morbo Gallico that is “Concerning the French Disease”[24]. In this regard, he was not just making a Francophobic allusion to syphilis; he was referring to government by absolute monarchy personified by Louis XIV of France. In the Two Treatises of Government, Locke, like Bernard of Arbroath, proceeded from the Christian premise that people are all born free and equal in dignity to the conclusion that the people have the right to choose their governors, and indeed to depose an anointed monarch who had forfeited their trust and thus their allegiance.

The Constitutions of Australia and the United States would embody these insights establishing limited governments in which ultimate sovereignty reposes in the people[25].

The Separation of Powers

In the thinking of Locke and Montesquieu the constitutional notion of the separation of powers emerged in order to ensure observance of the limits placed upon legitimate government. The conception in which each branch of government must be checked and balanced by the other branches of government in order to maintain constitutional limits on the power of the State recalls Augustine’s pessimistic view of human nature. Montesquieu observed that the objective of the separation of powers was not efficiency – autocracies are often very efficient – but the protection of the liberty of the governed by preventing the concentration of governmental power to restrict individual freedom and the retrospective imposition of greater control.[26] John Locke explained in his Two Treatises of Government[27]:

“for the same Persons who have the power of Making Laws, to have also in their hands the power to execute them … they may exempt themselves from Obedience to the Laws they have made, and suit the Law, both in its making and execution, to their own private advantage.”

This is the careful pessimism of Augustine in contrast to the optimism of Rousseau. More recently, Jeremy Waldron has said, if the processes of making, adjudicating upon and enforcing laws is in the same set of hands, those hands may “direct the burden of the laws they make away from themselves.”[28]

The conception in which each branch of government must be checked and balanced by the other branches of government in order to maintain constitutional limits on the power of the State recalls Augustine’s pessimistic view of human nature.

A major difference between the practical working out of similar arrangements in Australia and the United States relates to the role of judicial power in giving effect to limits on the powers of the State, and in particular in the case of the United States in the respect of the extensive guarantees of privacy, both express and implied, in the US Bill of Rights. With us, elected representatives of the people in their Parliaments take the leading role in the drawing of the line between Church and State, and between the public and the private. In the United States, the Supreme Court in fixing the content of the broad language of the Bill of Rights has come to exercise the role of a super-legislature. The exercise of this role by the Supreme Court has, in recent years, deeply unsettled the political balance outraging people on the both right and left of politics in turn.

In consequence of the unavoidably political nature of the decision-making of the US Supreme Court in interpreting the Bill of Rights, the appointment of federal judges has become a highly charged political issue in the United States. CNN’s exit polling of the 2016 US Presidential election disclosed that, for 56% of those who voted for the Republican candidate, Supreme Court appointments were the most important factor in their vote, with only 37% saying that this issue was not important to them[29]. The Republican candidate himself well understood the rage reflected in these figures, and he was astute to exploit it to the full. It was a major part of his political strategy. He told a rally in July 2016 that even if his conservative constituents didn’t like him they would have to vote for him anyway. “You know why?” he asked: “Supreme Court Judges”, he answered.[30] And in this respect at least, he did not disappoint his constituents.

Conclusion

To return to the lamented decline in the influence of Christian institutions and values, with which we began, if one looks beyond the numbers physically assembled in church each Sunday, it might be argued that the freer, more equal, and more compassionate society in which we live is a compelling manifestation of the enduring and ongoing success of the Christian message.

As to the waning influence of Christian institutions, it may be said that since the time of Constantine‘s takeover in the 4th Century, the record of Church bureaucracies of all denominations has sometimes been less than inspiring. For some it may even call to mind the observation that “the simplest way to explain the behaviour of any bureaucratic organisation is to assume that it is controlled by a cabal of its enemies”[31].

It might also be said that when engaged Christians speak of “Christian values”, there have always been differences between them as to what those values actually mean in practice. Franklin Roosevelt said of the social welfare program of the New Deal that it was “as old as Christian ethics, for basically its ethics are the same … It recognizes that man is his brother’s keeper, insists that the labourer is worthy of his hire, and demands that justice shall rule the might as well as the weak.”[32]. I suspect that many Republican voters in the United States at that time would have disagreed with FDR; and I have little doubt that the bulk of today’s Evangelical Christians who enthusiastically support the Republican candidate for President would regard FDR’s words as wicked heresy. For many other Christians it may seem a world-class irony that American Evangelicals might well re-elect as their President a proud and untroubled stranger to the most basic Christian notions of continence and compassion.

However…difficult it may be to draw the practical line between the things that are Caesar’s and the things that are God’s, between the public and the private, it is the recognition that there is a line that must be drawn, and respected that is the big point. That …is what distinguishes liberal democracies from totalitarian societies both of the left and right, from autocracies and from theocracies who claim to speak for God in the civic life of their communities.

However that may be, and however difficult it may be to draw the practical line between the things that are Caesar’s and the things that are God’s, between the public and the private, it is the recognition that there is a line that must be drawn, and respected that is the big point. That this line must be drawn, by the people, and respected, by the State is what distinguishes liberal democracies from totalitarian societies both of the left and right, from autocracies and from theocracies who claim to speak for God in the civic life of their communities. Of that we should be constantly mindful.

The tensions between the individual right to self-realisation and the claims of the community are profound. They necessarily fall to be resolved by each generation. In liberal democracies like the USA and Australia, that resolution occurs within a political framework shaped by the evolution of a distinctly Christian understanding of the relationship of the individual with the State and the equal dignity of each individual in his or her search for happiness. Liberal democracies may struggle in their response to the conflicting demands of their people, and they may enjoy differing degrees of success. But the inspiration abides.

President of the Queensland Christian Lawyers’ Society, David Cormack, wrote in respect of the above lecture:

The Queensland Christian Lawyers’ Society and the Australian Christian Legal Society had the privilege and honour of hosting the inaugural Honourable Bruce McPherson CBE memorial lecture on 21 March 2024 in Banco Court, Brisbane.

President Debra Mullins AO, Chaired. The Honourable Geoffrey Davies AO delivered a statement on behalf of Mrs McPherson. Mrs McPherson recounted that Bruce was born in 1936 in a small mission hospital in Melmoth, South Africa. Later, he attended Cambridge University, where he met his first wife, an Australian, and Bruce migrated to Australia to marry her. At that time, South Africa was under apartheid, and it was not an environment in which Bruce wanted to raise his family. Bruce lectured at the University of Queensland and completed his PhD in “The Law of Company Liquidation”, the basis of the seminal text first published in 1968. The honour board at the University of Queensland states that Bruce’s PhD was the first in Law.

Mrs McPherson recounted that it was widely thought that the thesis was worthy of an LLD, which Bruce ultimately received as an honorarium. Bruce left the University of Queensland and went to the Bar.

In practice, Bruce would decline to raise his fees despite solicitors begging him to do so, otherwise, (they believed) their clients would think he was no good. Bruce was a prime example of “the Protestant work ethic” and would not be dissuaded about his fees.

Mrs McPherson recalled Bruce lecturing her in the winding-up part of company law, and she went on to instruct him as an articled clerk in Canfield Pastoral Company v Dixon. With fondness, Mrs McPherson retold that love blossomed, and they were eventually married in 1975 at the Ann St Presbyterian Church, where she still worships. That same year, Bruce took silk and, in 1982, was appointed to the Supreme Court.

Mrs McPherson stated that Bruce was never happier than when immersed in the law and took great pride in writing his judgments, which he did in longhand. Bruce steadfastly refused to use a computer. Mrs McPherson recounted that Bruce was a heavy smoker, and when the Supreme Court issued a prohibition on smoking in the building, Bruce, as Senior Puisne Judge, made a rule that he could smoke in his chambers. However, smoking since the age of eighteen caught up, and Bruce was ordered by his doctors to give up and died peacefully in his sleep in 2013.

In closing, Mrs McPherson noted that Bruce’s interests were varied and included history, literature, reading, classical music (except Wagner), light opera, archaeology, astronomy, ornithology, volcanology and gardening.

Mrs McPherson expressed gratitude to those attending and said Bruce would be smiling.

David Cormack, President of the Christian Lawyers’ Society, welcomed and thanked attendees, including the Chief Justice and the Honourable Susan Kiefel AC KC, for their attendance.

The lecture’s genesis followed the Queensland Christian Lawyers’ Society’s 20th anniversary in 2020 and a review of its history, in which it was recalled that its inaugural President was the Honourable Bruce McPherson CBE, a position he held until he retired from the Queensland bench in 2006.

Mr Cormack stated his personal interest was sparked when he learned McPherson was from South Africa, the same country of origin as Mr Cormack.

Mr Cormack stated that McPherson’s legacy and contribution to the law are immense, as demonstrated by the persons in attendance at the lecture. Furthermore, it was notable that a festschrift on his retirement in 2006, entitled “Justice According to Law,” was published with a foreword by the Honourable AM Gleeson. It was the first for a Queensland judge.

Mr Cormack reflected that the speaker, the Honourable Patrick Keane AC KC, wrote in Hearsay on McPherson’s passing that in twenty years’ time, barristers will still cite McPherson’s judgments for their lucid and authoritative statements of principle, which was indeed well underway.

Mr Cormack noted that, in addition to judicial positions, McPherson served from 1969 as a member and chairman of Queensland’s Law Reform Commission until 1991. In 1988, the Queen’s Birthday Honours list awarded McPherson the Commander of the British Empire (CBE) for his service to law reform.

Mr Cormack remarked that McPherson was proud of his Scottish ancestry and by dint of being a Presbyterian. McPherson was actively involved in the Presbyterian Church and was its chairman of trustees for the Peirson Memorial Home for Children since 1988. A trust which continues its work today.

Mr Cormack remarked that McPherson’s donated papers to the Supreme Court Library include a speech to the Elders and Managers of the Presbyterian Church at Wavell in 1990. The topic was the “Church and State in Australia” and specifically about “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s”. A topic as relevant today as it was when it was said 2000 years ago.

Mr Cormack reflected that much more could and ought to be said about McPherson’s humanity, numerous published works, role as Chairman of the Supreme Court Library collection subcommittee, member and international vice-president of the Selden Society, Chairman of the Judicial Conference of Australia, Acting New South Court of Appeal judge, member and one of the deputy presidents of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, judge of the Court of Appeal of the Solomons Island and judge of the Fiji Court of Appeal, but not tonight.

Mr Cormack concluded that the Queensland Christian Lawyers’ Society is grateful and humbled that McPherson was their president.

The Honourable Patrick Keane AC KC delivered the “Christian Inspiration and Constitutional Insights” lecture. It reflected McPherson’s legacy and perspective and his Honour stated:

“For McPherson, the cardinal judicial virtue was not a passionate commitment to doing what one finds personally agreeable, but fidelity to the rule of law…. He was firmly of the view that justice is not a matter of judicial benevolence or of second guessing the legislative efforts of the elected representatives of the people. Bruce did not approve of the jurisprudence of the warm inner glow… But the wisdom of McPherson’s modest view of the proper scope of judicial power is apparent in the convulsions wrought in the United States by popular outrage on all sides of politics, against decisions on political questions by a judiciary that is seen to act as a super-legislature.”

In this vein, the paper addressed “the extent to which the constitutional arrangements of the liberal democracies in Australia and the United States actually embody an understanding of the relationship between the private individual and the community and its public institutions that is distinctly Christian in its inspiration”.

* Formerly a Justice of the High Court of Australia. Non Permanent Justice of the Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong.

[1] A.T. Denning, “The Influence of Religion” in The Changing Law (London, Steven & Sons Ltd, 1953) 99 at 107.

[2] (London, Stevens & Sons Ltd, 1955) at 1-3.

[3] In XIX.

[4] Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Philadelphia. R. Bell, 1776) at 12.

[5] Montesquieu, quoted by Paul Strathern in Ten Cities That Led the World: From Ancient Metropolis to Modern Megacity, Hodder & Stoughton, 2023 at 76.

[6] Max Farrand (ed) The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (1937) Vol 1, 486.

[7] Joseph J Ellis, The Cause: The American Revolution and Its Discontents, 1773-1783 Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2021, at 86-87. See also Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States WW Norton & Company, 2018, at 98-99.

[8] Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States, WW Norton & Coy, 2018 at 132-133.

[9] Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States WW Norton & Company, 2018, at 200-201.

[10] John Locke, Second Treatise of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration,ed Mark Goldie; Oxford University Press, 2016 at 4, 63.

[11] Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States WW Norton & Company, 2018, at 278.

[12] Alcuin Letters 113.

[13] Alcuin Letters 113.

[14] Marsilius of Padua, The Defender of the Peace ed Annabel Brett Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought, Cambridge University Press, 2005 at p 548.

[15] J. Healey, The Blazing World: A New History of Revolutionary England, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023 at 258.

[16] Robert Zaretsky, Boswell’s Enlightenment, Cambridge MA, and London: (Harvard University Press 2015) 132, 145.

[17] Section 116 of the Constitution provides: “The Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.”

[18] John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, London: Collier Macmillan Publishers, 1950) 18.

[19] Tom Holland, Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind, Little, Brown, 2019, p386.

[20] Thomas Acquinas, In octo libros politicorum Aristotle’s exposito, ed, R M Spiazzi (Turin, Mariotti, 1966) p.120 (in 225).

[21] Marsilius of Padua, The Defender of the Peace,ed Annabel Brett Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought. Cambridge University Press, 2005 at pp 548 and 548.

[22] Jenks, “The Myth of Magna Carta”, (1904) 4 Independent Review 260 at 268.

[23] Ibid at 188.

[24] Jonathan Hesley, The Blazing World: A New History of Revolutionary England, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023 at 394.

[25] Constitution, Ss7, 24, 94 and 125.

[26] Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, Thomas Nugent (trans) (1873), Bk II, Ch 6 at 171-174.

[27] Locke, Two Treatises of Government, Peter Laslett (ed), 1988 at 364.

[28] Waldron, “Separation of Powers in Thought and Practice” (2013) 54 Boston College Law Review, 433 at 446.

[29] https://edition.cnn.com/election/2016/results/exit-polls.

[30] The Economist September 15, 2018 at 20.

[31] Robert Conquest’s third law of politics, quoted in Mick Herron, Slough House, Baskerville, 2022.

[32] Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States,WW Norton & Coy, 2018 at 430.

It occurs to me that the topic of my address might be a little misleading. As someone who has been a judge for only eight years, and was an advocate for twenty-seven years before that, my view from the bench is still very much framed or shaped by my experience as an advocate.

In the thirty-five year period that I have been involved in the practice of the law, large changes have taken place to the dynamics that drive the conduct of advocacy in our Courts.

Culturally and structurally, the example of the United States has affected the practices of the legal profession, and of the Courts, just as they have influenced our economic and social life more generally.

But while there has been great change, we have succeeded in retaining a central feature of our system of administration of justice which distinguishes us from the United States. That feature is the notion that lawyers are officers of the Court and that as such, their first duty is to the Court and, through the Court, to the administration of justice.

In the highly successful television program “Rake”, the protagonist Cleaver Green of Counsel, speaking of the work of a barrister, says: “It’s all bullshit, mate; it’s just smoke and mirrors.”

He sounds entirely like the cynical lawyers of American legal TV dramas. And I suppose we all know some hard-bitten cynics who do take this view of the administration of justice. But happily, I do not think that it is a view which characterises the Australian legal profession or the Bench.

Only someone who doesn’t actually practise law could think that Cleaver Green’s attitude is representative of the legal profession in Australia.

Producers of popular television programs and journalists, who wear their world weary cynicism as a badge of honour, are, of course, free to say what they like. In doing so, they are unconstrained by the discipline imposed uniquely on lawyers by the pressure of argument in open court where error and hyperbole are quickly corrected. Actually doing the business is important to an understanding of what it reveals about those who are doing the business.

There is a story about Talleyrand, the great survivor of the French Revolution, which illustrates my point.

One of the five-man Directory which ruled post-revolutionary France before the coup which brought Napoleon to power, was Louis-Marie de la Reveillière-Lépaux. He was an intellectual who had founded a new religion which he called “theophilanthropy”. He gave a public lecture on his new religion which was attended by Talleyrand. Afterwards, Talleyrand said to him:

“… I have just one observation to make to you. Jesus Christ, in order to found his religion, was crucified and rose from the dead. You should try to do the same.”

And so I am confident that you, as people who are actually trying to do the business, do think about what you do as something in which duty is more important than self-promotion and that you are not tempted to think that a failure to do your duty by the system does not really matter because the system “is all smoke and mirrors”. That, after all, is why you are at this conference.

Instead of the cynicism of Cleaver Green, I would commend to you the words of Sir Maurice Byers, who was one of the most successful advocates ever to appear in the High Court. He said of the role of the advocate:1

“When we appear before the courts, we are engaged in the administration of justice and thus owe to the courts in this ministerial undertaking a duty which prevails over our duty to our client. The practice of the law is thus radically and essentially different from the practice of other professions or callings. We participate and they do not in the administration of justice to the same extent as the judge, though our function differs.”

Civility

While I was at the Bar, I acted on a number of occasions for and against litigants from the USA. On most occasions, the American client was represented by an in-house lawyer. Invariably, at the end of each case, the in-house lawyer for the client would comment that they were very impressed with the civility which prevailed in our courts, not because it was quaint and olde-worlde, but because it meant that the solution of the legal problem at hand was plainly the sole focus of the proceeding, and the civility of the debate meant that arriving at the best solution was more likely.

The civility which prevails in our courts is an enduring outward sign of the co-operative view of the administration of justice in which the advocates for each side act as officers of the Court, duty-bound to assist it. This is a radically different model from a system in which advocates may engage in any conduct, it seems, short of an actual crime, to advance the client’s interests.

Sir Nigel Bowen, at the foundation of the Federal Court in the mid-1970s, stated that his ambition for the Court was that it should be a Court of “excellence, innovation and courtesy”.

It must have struck many lay people at the time as odd that a judge would think to express the hope that a court should be courteous: surely it should go without saying that a court should be courteous.

While that might be so now, it was not necessarily so when Sir Nigel was speaking.

I can certainly vouch from my own experience as a fledgling lawyer in the 1970s that the Courts were sometimes unpleasant places to appear for advocates.

In those days, of course, they were universally presided over by men. These men were usually very angry — about something, which usually eluded everyone else. Those courts were occasionally so unpleasant as to put one in mind of the Royal Navy of Nelson’s era, described by Winston Churchill as a place of “Rum, sodomy and the lash!”

That, happily, has certainly changed. The increasing numbers in which women have taken their place on the bench has obviously been an important influence for the good.

But even in those somewhat more fraught times, judges were conscious that the transparency and rationality of judicial decision-making processes were values of the highest importance. That judicial decisions are made by a disinterested person, on the basis of evidence and arguments fully and fairly ventilated in open court, is essential to the maintenance of public confidence.

And it is now almost universally acknowledged in the superior courts of the Commonwealth that civility on the part of the judges is good policy because the performance of the legal profession is unlikely to be at its best or most helpful if it is being hectored by the bench.

Judges know that skilled lawyers are the most important resource available to the courts in doing justice, and we need to help them to be heard, not to make their difficult and important job even harder.

The explosion of legislation and regulations has been another important change in the dynamics of the justice system over the last four decades. The predominance of legislation as the source of law means that statutory interpretation is more the focus of the judicial function now than the judicial development of the common law. One consequence of this development is that there is less scope for the emergence of judicial figures as dominant forces in legal development.

We are now less likely to see the emergence of a hero judge, such as an Atkin or a Denning or a Dixon. Even the most forceful judicial personalities are less likely to feel the need to demonstrate that they are the smartest person in the Courtroom and destined for a place in the history books with the great lawyers of past centuries.

At least, that is the case in Australia. I was surprised, recently, to see a newspaper report of a serving American judge making a speaking tour to promote her autobiography. In the course of this triumphal progress, her Honour expressed the modest hope that her judicial opinions would be regarded in future decades as among the best produced by any judge of her Court.

By and large, I think that it is fair to say that in Australia our judges’ feet have generally been kept firmly on the ground by the constraints of our egalitarian democracy and an ethos of judicial modesty.

As for the history books, the best any of our judges can hope for, in terms of what people might say about us in three or four decades into the future is: “Isn’t it remarkable that he’s still sexually active.”

This morning I will mention a number of aspects of advocacy which bear upon the maintenance of the relationship of mutual confidence between Bench and Bar which is central to our mechanism for the doing of justice. To the extent that there is a unifying theme to what I hope are helpful hints, it is the idea that we are all, judges and advocates, engaged in a mutually respectful cooperative enterprise which is not all “bullshit and smoke and mirrors”.

Trials

Thorough trial preparation has always been essential. It is even more so by reason of the technological revolution. The worst failure of which an advocate can be guilty is a lack of preparation.

From the point of view of the judge, the unprepared advocate is less than useless because of their potential to unwittingly mislead the court. That is especially so in trials where there is a large volume of documents. The greatest assistance an advocate can provide is to reduce and refine the evidence which the judge must digest to decide the case.

The abundance of documents to which critical human intelligence has not been applied before trial is one of the greatest problems for trial courts. The worst advocacy I have ever seen occurred in a long trial where the advocates opened the case by meandering through a bundle of documents — whether physically or electronically — with a view to seeing if there were any documents which the judge might think were interesting.

The process of discovery has become so burdensome that it has spawned a separate industry to help lawyers cope with it. The lawyer who can marshal the crucial documents is highly valued by the judges. The best advocate ensures that the force of the documents which most strongly support the client’s case is not hidden under bushels of dross.

The second worst thing I have seen in an advocate at a trial is a refusal by Counsel for the defendant or respondent of an invitation by the Court to open his side’s case immediately after, and in response to, the plaintiff’s opening. Such a refusal can only be explicable by poor preparation. No advocate worth his or her salt would pass up the opportunity to restore the balance which you must assume has been tilted, albeit provisionally, in favour of your opponent’s case.

Mediation

Can I return to mediation. The involvement of specialist advocates in mediation is a phenomenon of the last two and a half decades.

There are still advocates in practice who regard it as a badge of honour that they refuse to attend mediations. But the vast majority recognise that it is a great thing to help litigants resolve their disputes without the need for a trial. The clients get to keep their dignity and exercise their autonomy rather than have the solutions to life’s problems imposed on them by others. Just as importantly, they save time, money and distraction.

Once again, thorough preparation is essential if advice is to be clear, responsible and effective.

It may well be that some advocates, especially the younger ones, may feel that heavy involvement in mediation is dulling your forensic edge. If you do feel that your court craft needs some polishing because you aren’t getting to court as often as you would like, my advice would be to go and sit in on a criminal trial in the Supreme Court. And especially, if you are struggling with the discipline of being concise and relevant, go and watch some criminal appeals in the Court of Appeal. You will see masters of relevance in action.

Speaking parochially for a moment, it was my experience on the Court of Appeal that one of the glories of the Queensland Bar is the quality of the advocacy in criminal appeals.

Written Arguments