FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 91: Mar 2023, Reviews and the Arts

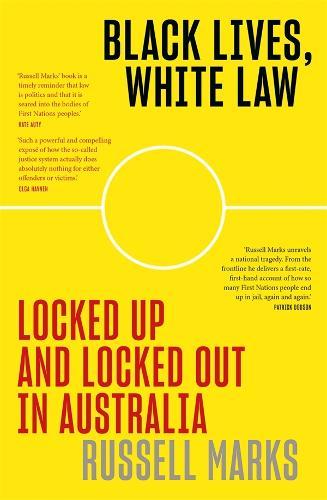

Author: Russell MarksPublisher: La Trobe University Press in conjunction with Black Inc BooksReviewer: Brian Morgan

This recently published book has done what I think all good books should do. It has made me consider or reconsider my position in relation to First Nations people and the way they have been treated by our legal system and how they are still being treated by it.

At the outset, let me say that I disagree with many of the apparent conclusions made by the author. This is not to say that one or other of us is wrong.

Russell Marks provides a great deal of information that is not otherwise readily available concerning various changes wrought by the criminal justice system to affect First Nations people from 1788 onwards. He summarises a large number of detailed examples so that one does not need to rely on his conclusions but can see at second hand that, from the earliest days, First Nations people (a term which I prefer to use to describe those who lived in Australia for many thousands of years) were treated as if the White Man’s law applied to them and that law was applied as if First Nations people understood the colonial concepts of right and wrong and accepted that the White Man’s legal system applied to them.

This was hardly ever likely to be true since the authorities who were running the system of justice had failed to understand that they had, themselves, invaded established civilisations in breach of the laws of those civilisations and purported not even to understand that the land they had stolen by armed force was both populated and ruled by sophisticated laws and customs.

As a result, there was little attempt by Courts and authorities to try to understand the traditional systems for dealing with members of various First Nations who transgressed. Rather, such people were and are, still, imprisoned in large numbers and frequently refused bail for minor offences where, by the time of trial, they may have served more time in prison than if they pleaded guilty at the time of their first appearance in a court. This raises the question, what is the basis for refusing bail to First Nations people when non-First Nations people would be bailed?

Marks makes the point which I have observed, myself, that, frequently, First Nations people will insist on pleading guilty, whether or not they might have a defence, in order to avoid being locked up pending a trial which, almost certainly, will take place months into the future.

(On the subject of the word “pleaded” the author frequently uses the Americanism “pled”. I found this to be most distracting.)

The role of police, from earliest times, in obtaining a written confession in the best Queen’s or, I should now say, King’s English from people who could hardly string half a dozen words of English, together, and Courts accepting these as genuine confessions took me back to my early days as a barrister before we had videoed interrogations when these were commonplace.

The written confession was in my experience, always, suspect. The author summarises many examples where no rational person could think that the words were uttered by the accused. In one such case, my client had not progressed beyond Primary school but was reputed to have said, “I hope the Court will be lenient on me. I am a first offender”. But, time and time again, Courts accepted the reliability of such documents. My jury did not.

The role of White Law in respect to First Nations people has been the subject of many inquiries, a Royal Commission or two and a large number of articles and papers. Many recommendations for change have been made but not implemented.

In 1978, I spent some time in the Northern Territory on one of the large cattle stations. There were many First Nations families living there and most of the men worked for that station. The no doubt well-meaning Government ordered that, instead of the ramshackle accommodation occupied by the workers, new white man style houses were to be built, with toilets, running water and the usual facilities.

Within a short time the roofing iron had been removed and those houses, or what remained of them, were of no use as dwellings. The former inhabitants had used the materials to rebuild the humpies in which they were most at home. One wonders to what extent the First Nations workers for whom the new accommodation was being built were asked about how their living conditions could be improved and, if so, to what extent their answers were heard and acted upon.

If, in the mid 1970s, a government could still not understand that their wishes were different to “the natives”, how much more difficult was it, and is it, to appreciate how the colonial system of law and that of First Nations people are so different?

This book is informative. You might find yourself coming to the conclusion that we, as lawyers, whether prosecutors, defence lawyers, magistrates, judges or academics have yet to produce a satisfactory answer to this publication’s title, Black Lives, White Law: Locked Up and Locked Out in Australia and how the two are to be accommodated.

Not to underestimate the complexity of the task involved where First Nations people and people with diverse other heritage live among and interact with one another, perhaps, the words of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Persons, to which Australia is a signatory,provide guidance with their emphasis on phrases such as “self-determination” and “free, prior and informed consent”.

Black Lives do matter as the author reminds us.