The excellently-named Ratcliffe Pring is recorded on the Bar website as being the first Barrister who was enrolled on the roll of Queensland Barristers, which was established after 1859. Apparently the entry reads “Ratcliffe Pring, Inner Temple, 8.6.1849”.

Ratcliffe Pring is not much remembered these days, apart from the fact that he has a residential room at the Brisbane Tattersalls Club named after him as well as Pring Railway Siding near Bowen and the Parish of Pring in the same District.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography records in some detail Pring’s rather turbulent career in Queensland, both as Counsel, Legislative Drafter, Politician and Judge. The dictionary records that Pring was appointed Silk in 1868 and that in 1875 he was appointed a Judge of the Central District Court, but “resigned next year to accept a large fee in defence of a prominent business man”. Pring did another stint on the bench as an Acting Judge following the death of Lutwyche, J. with the dictionary noting that he was distinguished by the number of times he concurred with other Judges.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography records in some detail Pring’s rather turbulent career in Queensland, both as Counsel, Legislative Drafter, Politician and Judge. The dictionary records that Pring was appointed Silk in 1868 and that in 1875 he was appointed a Judge of the Central District Court, but “resigned next year to accept a large fee in defence of a prominent business man”. Pring did another stint on the bench as an Acting Judge following the death of Lutwyche, J. with the dictionary noting that he was distinguished by the number of times he concurred with other Judges.

The dictionary paints a portrait of his personality as being “impulsive, vain, hasty in temper, strong in opinion and forcible in expression.” There is even a suggestion that he was fond of a cold drink on a hot day.

The fact that Pring has a North Queensland Parish named after him seems at first glance a little mysterious. In fact, Ratcliffe Pring performed a Royal Commission duty in North Queensland which had long lasting effects for the mining industry in this State. The Dictionary of Biography merely records that in 1871 he was appointed as “Commissioner of Goldfields, charged to visit them and suggest their future legislation.”

That simple description of his Royal Commission task does not do justice to the man or the legislation he subsequently drafted, which was the statutory precursor to all modern mining legislation. His legislation is described as “an act for the management of goldfields” and was given royal assent in 1874 as The Goldfields Act 1874.

With characteristic efficiency, Pring visited the northern goldfields within a month of the receipt of his commission. C.A. Bernays, “Queensland Politics During Sixty Years” (Brisbane 1919) describes him as “an exceptionally industrious legislator……..a vigorous speaker with a hasty temper and a very remorseful nature after his frequent outbursts had subsided.”

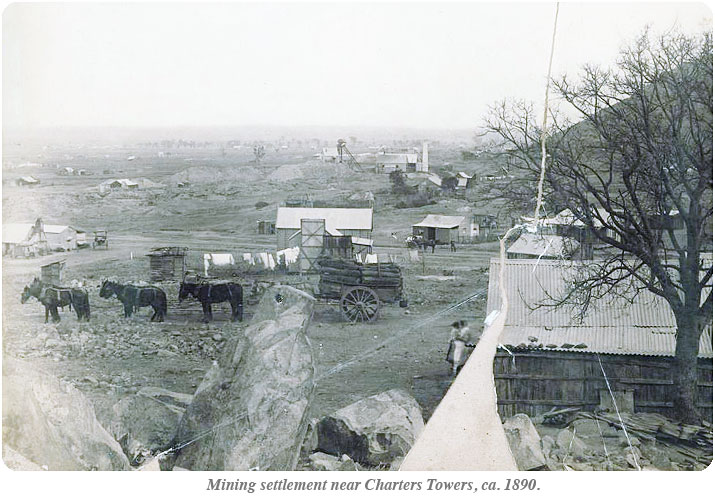

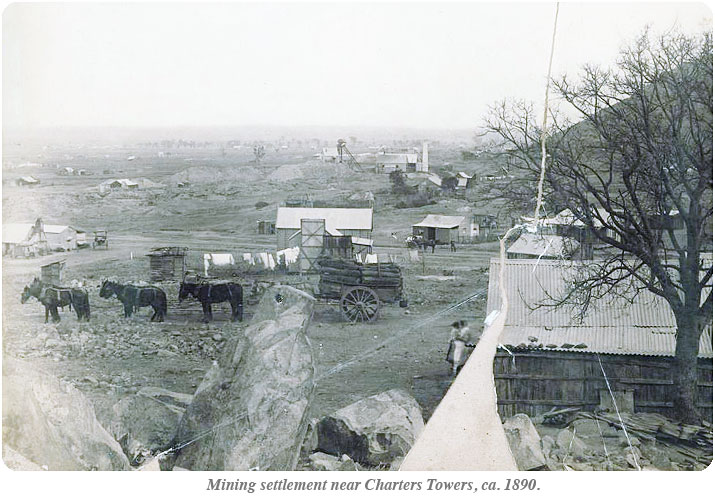

The contemporary record of Pring’s activity shows that immediately upon accepting his commission, he departed from Brisbane to the north on a State Government owned vessel. Upon reaching Bowen he mounted a horse and rode west to Cape River and to the Charters Towers goldfields, which were then in their infancy. He returned to the then embryonic Townsville where he again embarked on a vessel for Cooktown and other small gold mining centres in the far north, including a visit to the distant Palmer River goldfields which were accessible only by a very hazardous and arduous track through the “Hells Gate” country, populated by very fiercely protective aboriginal people.

Pring returned to Brisbane by sea and during the voyage apparently drafted his report and the legislation.

All of this activity took approximately six weeks between acceptance of the commission and the production of the legislation. It must be a record which has not since been beaten.

Background to Pring’s commission

Between the years 1859 and 1874, the Queensland legislature dealt with the mining activity of the new colony in a piecemeal fashion. Various statutes empowered the Governor-in-Council to alienate Crown lands for mining purposes other than gold mining. Examples of these were the Crown Lands Alienation Acts of 1860 and 1868 whereby purchase of up to 640 acres at One Pound per acre was possible. Another was the Immigration Act 1864.

The first statute passed by the Queensland legislature connected directly with the product of mining was the Gold Export Duty Repeal Act 1860, although this related to gold won in New South Wales. Other statutes dealt with ancillary mining matters – for example The Gold Fields Town Lands Act 1869 and its replacement, the Gold Fields Homestead Act of 1870, which allowed miners to gain security of tenure through leases over land they occupied, with the possibility of purchasing the freehold title upon expiration of the lease. The 1868 Rules of the Gympie Local Mining Court which regulated proceedings on that goldfield, which had been discovered in the previous year, complemented the early mining-related laws. (C.A. Bernays (op cit) notes that the language of the Gympie rules “was materially different” from that in use in his own time, (1919) “there being several instances in which nominatives and verbs are in strong disagreement with one another”.)

In 1870, the importance of mining to colonial development and the realization that the patchwork of inherited law overlaid by the patois of the Gympie Mining Warden Rules would be inadequate for effective regulation of the now booming goldfields, was the cause of the Royal Commission being issued to Ratcliffe Pring.

In his report, Pring noted “the apathy (towards the Royal Commission) of the miners seems remarkable…..although a general feeling of satisfaction seemed to pervade the community that their interests had been thought of.”

Pring quickly realized that the early mining industry relied heavily on the prospecting endeavours of individuals and therefore his Act’s major provisions focused on leases, consolidated miners’ rights and the size of claims.

Leases

Under the 1856 New South Wales statute, the Governor-in-Council was empowered to grant leases in auriferous areas. Pring’s inquiry found “among working miners a strong objection to this system based on the ground of monopoly of gold lands”. The new Act and Regulations gazetted in October 1874 provided for the grant of leases of not more than twenty-five acres for terms up to twenty-one years at the rental rate of One Pound per acre per annum with a moratorium on the grant of such leases for two years following proclamation of a field. The compensation provisions for occupiers of such land were now incorporated into Pring’s Act. Section 12 stated that such leases were voidable at the will of the Governor should lease conditions be breached or for non bona fide use. The Regulations further “fleshed out” the protections against monopoly and speculation by providing a stringent set of working conditions. Whereas the 1870 Regulations had attempted a complete management scheme covering such diverse matters as leases of auriferous tracts (Regs. 78 to 82) and the marking and stacking of quartz stone (Reg. 71), their provisions were regarded by administrators and miners alike as “so vague and ambiguous in expression, that no uniform or intelligent legal construction can be placed on them.” Pring’s Regulations were much more precise, particularly in the application process and the survey requirements for leases. Furthermore, Mining Wardens could assess the number of miners required to work the lease so granted and the circumstances under which these working conditions could be relaxed. However, the Act and Regulations were silent as to the requirements regarding machinery erection, as Pring thought that this would “hamper the enterprise of lessees”.

Miners’ Rights

The unrest of the early 1850’s on the Victorian Diggings influenced the introduction of the concept of conferring rights on individual prospectors in relation to mining, occupation and title to gold found; the Miner’s Right was effective only in respect to wastelands of the Crown. It was adopted by the 1857 New South Wales legislation and therefore part of the mining law of Queensland after separation. By 1870 this emphasis on the rights of individual miners and the limitations on the areas of ground which could be worked by a party of miners had discouraged attempts to combine for a more systematic exploitation of a field. The new Act accordingly provided for a consolidated Miners’ Right which enabled companies and co-partnerships to exercise the statutory privileges outlined in Section 9. The privileges included the right to possession and occupation of Crown Land for mining purposes, certain timber and construction rights, water storage and diversion rights and residence rights. There was no limitation of numbers in co-partnerships. The possible time the Right might remain in force was increased to ten years at a fee of ten shillings per year. The Act further deemed property rights (and shares to such rights) gained through Miner’s Right tenure to be chattel interests rather than real property interests, but that notwithstanding this limitation on the land tenure in respect of claims under the Miner’s Right, the holders could assign or encumber the property (or any part of it) in order to finance mining operations. Regulation 33 of 1874 set up a registration system for liens given over shares or interests in claims, as security for payment of debts.

General Aspects of Goldfield Management

(i) “Frontage”

The pre-1874 law covering reefing contained some difficulties for administrators due to the system of “frontage” adopted in marking out the length of the claim; the width of the claim was considered less important because of the miners’ practice of following the lead or reef down. Unlike the deep leads of the Victorian Diggings, the geology of the Queensland reefing districts caused problems for administrators of goldfields. Following the line of a reef, miners frequently found themselves beneath neighbouring claims. The Gympie Warden’s rules and the 1870 Regulations introduced the requirement of pegging “block” claims, thus fixing length and breadth of individual areas to remedy an anomaly arising from Victorian legislation. Many claim holders under the old law regarded themselves as having the right of following the reef wherever it went. The 1874 Regulations reaffirmed the policy of block claims and increased the base line along the reef to fifty feet per claim.

(ii) “Payable gold”

Pring reported great dissatisfaction among miners over the requirement that should a claim be found to yield “payable gold”, a 100% increase in workers employed for at least the following three months was necessary. The interpretation of this requirement varied according to the goldfields in which the discovery was made, but on most the measure was mandatory irrespective of the subsequent yield of the mine. The main objection was the absence of a definition of “payable gold” and uncertainty as to whether the term took account of such variable charges as extraction costs and crushing expenses. The 1874 Regulations therefore deemed a quartz reef to be payable when the quantity of gold obtained equaled, in value, the sum which had been paid in wages to all miners of the working party actually employed thereon during the extraction and treatment process, together with the necessary crushing overheads. These two issues exemplify the minutiae which concerned the early miners and on the proper regulation of these issues depended the harmony and prosperity of the gold fields. Further examples, such as the regulation of dams, races, puddling claims and machinery areas, are in the 1874 Act and Regulations.

(iii) Existing pastoral leases

The New South Wales legislation gave the Governor-in-Council power to suspend pastoral leases extending over goldfields, subject to the proviso that such interference was allowable only so far as it was necessary for the accommodation of miner’s livestock, the supply of water and the effective working of actual mining areas. This was subject to a compensation clause. The 1874 Act was more specific, giving not only a suspension power but also allowing the possibility of absolute cancellation. This change to the law indicates the increasing importance of mining to the colony vis a vis pastoral interests. This has modern day echoes.

(iv) Business Licenses

The commercial interests of goldfields were also now subject to more specific regulation. A Business License entitled the holder to occupy up to a quarter acre for residence and business purposes. Individuals were limited to one such portion. The maximum license period was ten years at an annual cost of four pounds. Such licensees were deemed in law to be possessed of the surface of the land and the Act declared this tenure to be a chattel interest (rather than realty) which could be transferred by endorsements on the license document at a fee of five shillings.

(v) Administration of justice – Mining Wardens

Pring’s report noted that “the present provision for the determination of mining disputes and for exercising the right of appeal do not appear to give general satisfaction………and may well be unsuited to the gold mining community.” He successfully recommended a Warden’s Court for each goldfield with jurisdiction to try all cases concerning encroachments, claims to land and cases over rights to auriferous soil or stone. All matters in which pecuniary compensation was sought or money demands made, were also within its jurisdiction. Rights of appeal from the Warden’s Court lay to the District Court which was invested with an Equitable Jurisdiction as well as being given sole jurisdiction involving title to land. Pring specifically disapproved of the concept of elected local Mining Courts or Boards with regulation-making powers such as those which were the subject of an earlier Victorian Royal Commission in 1866 and the 1867 Gympie model. He felt the changes in the rules between the various gold fields “would greatly confuse and embarrass the miner on his removal from one goldfield to another.” Furthermore, this situation would “tend to depress the industry by creating a sense of insecurity in the holders of mining property as well as creating uncertain meaning and doubtful legality of laws, framed by those who, perhaps, may not possess sufficient legal knowledge for the purpose.” Pring also rejected the notion of a Central Board located in Brisbane.

The 1874 Act provided for appointment of Mining Wardens by the Governor-in-Council. Wardens could deal with matters before the Court either summarily by consent of the parties or in conjunction with two Assessors selected by ballot (subject to a challenge system similar to the jury selection process) from a list of 200 local persons “of good repute who shall be registered claimholders, machine owners, leaseholders or business licensees.” In addition to the normal court facilities such as a “payment in” mechanism, the Warden had special powers which indicate the unique nature of the Warden’s position on mining frontiers of that period. The Act conferred the power of granting injunctions upon the Warden, a measure normally the exclusive preserve of the Supreme Court exercising its Equity Jurisdiction. This power enabled the Warden to restrain persons from encroaching, occupying, using or working claims, races, dams and so on. Injunction also lay to the sale, damaging or interference with claims, machinery, stacked earth or gold. Such Injunctions could issue without notice and remain in force for seven days. Furthermore, the Warden could authorize surveys and trespass on claims to check encroachment allegations by litigants. By Section 51 the Warden could seize gold to satisfy debts, damages or costs found to be proved. Appeal regarding facts in issue lay to the District Court which conducted circuits to the larger goldfield towns, and such actions involved re-hearing de novo. Appeals on questions of law lay to the Supreme Court located in Brisbane, Rockhampton and Bowen.

Mining Wardens such as William Charters (after whom Charters “Tors” was named) were, indeed, legal potentates!)

(vi) Rewards for discovery of gold

Pring’s exhortation that prospectors’ services “should be recognized with no niggard hand” resulted in Section 97 of the new Act, which authorized a reward not exceeding One Thousand Pounds to the actual discoverers of any new goldfield. The Regulations further dealt with the mechanics of the notification of the location of gold discovered.

In the 40 years following the Pring legislation, no fewer than three further Royal Commissions were conducted into the mining industry, and as well the enactment of over 70 statutes and consideration of numerous short-lived Bills indicate the considerable time and energy expenditure of the Politicians and their lobbyists. The result was, despite one attempt at codification, a plethora of legislative measures which to lawyer and layman alike presented a labyrinthine set of rules as complex as the shafts and drives of the mines they purported to regulate. None of these legislative measures surpassed the clarity of the Pring legislation. (For a detailed treatment of Queensland mining law to 1972, see C.F. Fairleigh QC “Mining Law of Queensland” LLM thesis, University of Queensland, 1973.)

One feature of the legislation drafted by Pring was the exclusion of “Asiatics” and “negroes” from holding mining tenures such as leases. On the Queensland goldfields, there was a massive influx of Chinese immigrants who therefore had to content themselves with going through the mullock (waste) heaps of the European miners in order to win whatever gold remained. There are many old goldfields in North Queensland where one can still observe the traces of the industrious Chinese process of washing mullock heaps, which is evidenced by numerous large earthworks which transported water from one place to another in order to wash the mullocks.

This restriction was later incorporated into the Mining Acts generally.

The racist exclusion of persons who were not European from winning minerals from the Queensland earth continued until 1968 when the State Parliament repealed the prohibition. This repeal happened to coincide with the formation of the Thiess Peabody Mitsui Joint Venture which led to the modern development of the Queensland coalfields.

Pring’s legacy

Notwithstanding the less than flattering entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Pring’s industry and learning set high standards for the regulation of Queensland mining for decades after 1874. It is fitting that our Bar journal records this legacy.

Michael Drew

The Australian Dictionary of Biography records in some detail Pring’s rather turbulent career in Queensland, both as Counsel, Legislative Drafter, Politician and Judge. The dictionary records that Pring was appointed Silk in 1868 and that in 1875 he was appointed a Judge of the Central District Court, but “resigned next year to accept a large fee in defence of a prominent business man”. Pring did another stint on the bench as an Acting Judge following the death of Lutwyche, J. with the dictionary noting that he was distinguished by the number of times he concurred with other Judges.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography records in some detail Pring’s rather turbulent career in Queensland, both as Counsel, Legislative Drafter, Politician and Judge. The dictionary records that Pring was appointed Silk in 1868 and that in 1875 he was appointed a Judge of the Central District Court, but “resigned next year to accept a large fee in defence of a prominent business man”. Pring did another stint on the bench as an Acting Judge following the death of Lutwyche, J. with the dictionary noting that he was distinguished by the number of times he concurred with other Judges.