FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 93: Sep 2023, Reviews and the Arts

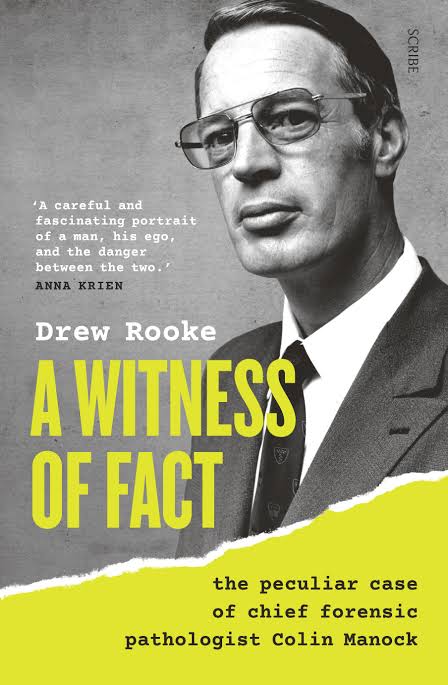

The peculiar case of chief forensic pathologist Colin Manock.

Author: Drew RookePublisher: ScribeReviewer: Samuel Lane

Manock’s flawed and fabricated evidence given to the jury, who were misled, took away nearly twenty years of my liberty before it was overturned by the Court of Criminal Appeal. Can you even begin to imagine what imprisonment for that period of time was like? More than 7,000 sunrises and sunsets that I never saw? Can you sit here today and even contemplate the everyday joys and happiness that you take for granted that I missed out on? – Henry Keogh

Every now and then we, as lawyers, will come across a case where an injustice has occurred. It might be that this is infrequent but, with humans being fallible, it is an inevitability. Human error is, no doubt, a common reason for these injustices.

What I hope is not common, however, is for one individual, through sheer disregard, ego and lack of qualifications, to be responsible for a great many miscarriages of justice. This uncommon circumstance, however, is the very reality that Drew Rooke has investigated and reported on in A Witness of Fact, when dissecting the career of the former Chief Forensic Pathologist of South Australia, Dr Colin Manock.

Between 1968 and 1995, Dr Colin Manock was the Chief Forensic Pathologist of South Australia, overseeing and conducting approximately 10,000 autopsies. By his own estimate, Dr Manock helped secure more than 400 convictions. Those numbers should be considered significant on any version of events but they take on a much more sinister and troubling significance once the reader has been able to digest the carefully researched reporting of Rooke in A Witness of Fact.

A Witness of Fact is divided into 3 parts, namely: The Man; The Cases; The Legacy. While not running in a strictly chronological fashion, the book largely traces the career of Dr Manock to reveal how it came to pass that he held the position of director of forensic pathology at South Australia’s Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science (IMVS, now SA Pathology) while “he was not formally qualified as a forensic pathologist, nor trained in histopathology.” It appears from Rooke’s reporting that the IMVS were “desperate” to find a director of forensic pathology and that, while Dr Manock was “very young and relatively inexperienced” having no “expert qualifications”, he was apparently the best applicant available and was appointed “in the hope that he would further study and progress.”

Part 1: The Man chronicles, to the extent that the information is available (noting that Dr Manock did not make himself available for an interview for the purposes of the book), Dr Manock’s educational background, personal life and other matters necessary to give the readers an insight into the man. Some of the details are more salacious than they are relevant to his work (he is, apparently, married to Mistress Gabrielle, a practising dominatrix in Adelaide), while others are included to provide some insight into his psychology (he is reported to be a gun enthusiast and would make his own bullets in his garden shed). But the author does go to great effort to give the reader a view into the mind of Dr Manock.

Perhaps, the most troubling revelation was the author’s description of an open-air autopsy that Dr Manock performed on the body of a deceased First Nations man in country South Australia, in full view of the public (this was after specifically refusing to use a more private setting indoors, that had been sourced by a police officer). A crude autopsy table was constructed by Dr Manock by placing a sheet of corrugated iron over two oil drums. The body was then placed on the sheet of iron, with Dr Manock proceeding to dissect the body, removing organs and dropping them into a bucket by the side of the body. Dr Manock then (for reasons that are entirely inexplicable) dipped a metal ladle into the body of the deceased and scooped out blood and bodily fluids. He then held up the ladle to the viewing public and jokingly quipped: “Anyone for soup?”

While the matters detailed in Part 1 of the book are deeply troubling in their own right, they are made much more so by the description of cases in Part 2 of the book.

Rooke has carefully reported on the description of a number of cases where Dr Manock, as chief forensic pathologist, has conducted autopsies which have led to miscarriages of justice. These cases have led to apparently innocent people being convicted of crimes. The equally disturbing corollary is that other people who may have committed the crimes have, never, been made accountable. The author has explained in detail how Dr Manock has given evidence in many cases in a manner that is strident and uncompromising. Even in cases where, according to the author, Dr Manock should have properly conceded matters, he remained steadfast and unwilling to make any concessions.

Perhaps the most widely known example is the case of Henry Keogh, who was convicted of murdering his fiancé by drowning her in the bath. The Crown case was entirely circumstantial and relied heavily upon the evidence of Dr Manock. Dr Manock gave evidence that he was certain that Mr Keogh’s fiancé had been drowned and that a bruise on her leg was evidence of a grip that had been used to pull her underwater.

Mr Keogh served nearly 20 years in prison before his conviction was quashed on a second appeal, under new legislation introduced in South Australia in 2013 allowing for a second or subsequent appeal. The Court of Criminal Appeal in South Australia considered that the trial process had been “fundamentally flawed” in large part because the evidence of Dr Manock had “materially misled the prosecution, the defence, the trial judge and the jury.”

While the author also thoughtfully analyses a number of other cases of miscarriages of justice, including the cases of Derek Bromley and Fritz Van Beelen, he also details concerning cases where Dr Manock has, carelessly and incorrectly, given innocent explanations for deaths, resulting in potentially guilty people walking free. It is particularly troubling that the cases set out by Rooke are those involving infants.

The work described as having been performed by Dr Manock in respect of three cases of infant deaths was so troubling to police officers and medical practitioners who were involved in them that the State Coroner, Wayne Chivell, decided to conduct an inquest into all three deaths.

While it is unnecessary to set out here the detail of each of these cases, it is worth noting that the injuries to each child were very troubling. Perhaps more troubling, though, was the apparently innocent explanation that Dr Manock gave for each of the deaths. As a result, the prosecution was unable to take matters further.

In Part 3, Rooke considers the legacy of Dr Manock, not just on those who may have suffered injustice at his hands, but also on the legal community and the administration of justice more broadly. Interestingly, there has been pressure for some time for a Royal Commission into Dr Manock’s conduct of cases. That pressure is yet to yield any results.

In fact, Rooke reports on a number of apologists for Dr Manock and, surprisingly, the fact that he has been celebrated in some parts of the scientific community, despite all that is now known about his lack of qualifications, his incorrect conduct of autopsies and his flawed and strident evidence in numerous criminal proceedings. For example, in 2005, long after serious questions had been raised about Dr Manock’s work, the South Australian branch of the Australian and New Zealand Forensic Society awarded Dr Manock its Award for Service.

Dr Manock, it seems, is not without peers. Other forensic pathologists, internationally, have been put under the microscope and have been found to have acted with similar self-certainty and ego as Dr Manock.

Rooke’s work in A Witness of Fact is a timely reminder that no one is infallible, not even a seemingly certain and experienced “expert” pathologist. In fact, Rooke’s work reminds us that treating such experts with unquestioned deference and regard might be doing us all a great disservice.