FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 93: Sep 2023, Reviews and the Arts

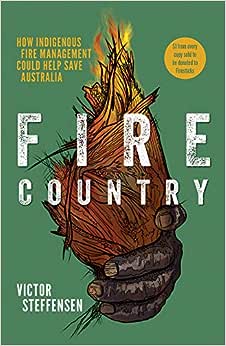

Author: Victor SteffensenPublisher: Hardi Grant TravelReviewer: Stephen Keim

Victor Steffensen has a Tagalaka heritage through his mother’s connections from the Gulf Country of north Queensland. He also has a German and English heritage from his father’s side. Steffensen’s Tagalaka maternal grandmother was separated from her family and was sent to work for a white cattle farming family. She died when Steffensen was five. Steffensen grew up in Kuranda and, although taught to be proud of his Indigenous heritage, learned little detailed cultural knowledge from his immediate family.

Entry into Canberra University to study cultural heritage was not the balm it promised to be in that a combination of Canberra’s cold weather and having to learn university-level English led Steffensen to drop out of university after three months.

So it was that, in the middle of 1991, Steffensen was invited on a fishing trip to the small Tablelands town of Laura. One of his fishing trip companions had Laura connections. Steffensen was fortunate to obtain a job on the local CDEP scheme and to be invited to live with Tommy George or TG, one of two brothers who were local elders. The direction of the next three decades of Steffensen’s life, and many years yet to come, was determined by that lucky break. The next day, Steffensen was introduced to TG’s brother, George Musgrave, or Poppy. It was from these two Awu-Laya elders that Steffensen learned the intricacies of traditional culture and it was with them that Steffensen embarked upon a journey of re-establishing traditional fire management of land.

Growing up in the 1920s, TG and Poppy had escaped being removed from their families by police officers through the good offices of the owner of Musgrave Station, Fred Shepherd, who would hide the boys in mailbags in the storeroom whenever police officers visited the station looking for Indigenous kids to remove from their families. As a result, TG and Poppy had managed to learn much more traditional knowledge than many others of their generation who had been removed from their families and their traditional country by the interventions of the state.

Fire Country is Steffensen’s memoir of how he learned traditional fire skills from the two old men and his journey with Poppy and TG into reapplying those skills to country. Mabo (No 2)[1] was decided on 3 June 1992 and, earlier, the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1991 had been passed allowing Aboriginal Australians to make claims to be recognised as owners of certain national parks and other government owned land.

As a result, it was reasonable to expect that the time was ripe for official recognition and facilitation of traditional fire management. While some signs were positive, Steffensen recounts in Fire Country many encouraging developments which turned sour and many official decisions which rejected traditional knowledge in favour of government knows best approaches. The difficulties associated with these early experiences, in some ways, served Steffensen well as he learned many people managing skills which helped him to turn resistance into cooperation as the traditional fire management movement spread and acquired adherents and supporters across the country.

Fire Country, as well as being a memoir, is a technical educational book. Steffensen explains the basic concept of the benefits of a cool fire which removes fuel load; does not destroy native plants; and promotes fresh growth. He also explains the dangers of hot fires, even those conducted to prevent wildfires, and the negative effects such hot fires have on fauna, flora, the soil and the country, itself. It also explains the detrimental impact of the absence of regular fires, not only the dangers it creates of destructive wildfires but, also, the effect that the build-up of fuel loads have in stifling fresh growth, marring habitat and promoting weed growth of vegetation not naturally suited to that type of country. Sick country is the appellation that would frequently come forth from elders such as Poppy and TG but, also, from Steffensen, himself, as his knowledge and teaching skills deepened.

Fire Country descends into greater detail describing, initially, with regard to Awu-Laya country, the correct seasons and times within the seasons for lighting fires by reference to the different ecosystems and soils and the way in which the vegetation of those ecosystems indicate their readiness to be burned.

Different timings and methodologies are explained by reference to boxwood and gum-tree country; stringybark and sand-ridge country; mixed tree systems; storm burn country and no fire country. By burning different country at the times suitable to that country, the customary fire practitioner produces the familiar mosaic pattern of customary fire practices and produces the safety associated with fire prevented from spreading out of control either by neighbouring country which is not yet ready to burn or which has already been burned and now displays non-combustible fresh green growth.

Steffensen was interested in recording and communicating the lessons he received from elders from the very beginning and his painstaking work has led to his becoming a respected filmmaker and sought after public speaker and communicator on Indigenous fire management of land as well as cultural knowledge, more generally. His work is supported by organisations like Firesticks and the National Indigenous Fire Workshops.

Steffensen’s knowledge and advocacy of such fire management has led to his giving lectures and practical demonstrations on country in many different parts of Australia and he has both learned from and assisted elders from many different Indigenous nations. We learn from these experiences of Steffensen that, even when an experienced fire practitioner is far from the country on which they learned their art, the land continues to talk to the practitioner so that the right timing and methods of burning can be devised from the information available to the careful and knowledgeable eye.

Fire Country was published in 2020. This was in the wake of the disastrous wildfires that, in the Black Summer of 2019-20, destroyed so much property, ended directly 34 human lives and destroyed so much fauna and flora of the Australian landscape. The closing chapters of Fire Country are written with the sadness flowing from that summer of tragedy but, also, with a heartfelt plea for Indigenous fire management knowledge to be taken seriously and to be adopted and applied more widely because of its ability to cure sick country and to prevent such disastrous and tragic wildfires from occurring in the future.

Steffensen’s work of teaching and communicating continues. He has published two children’s books since Fire Country, Looking After Country with Fire and The Trees: Learning Tree Knowledge with Uncle Kuu. Steffensen’s writing is another example of the obvious fact that, if a person wants to learn about important things, there will always be someone willing to share their information and knowledge.

[1] Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; 175 CLR 1