FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 97: September 2024, Reviews and the Arts

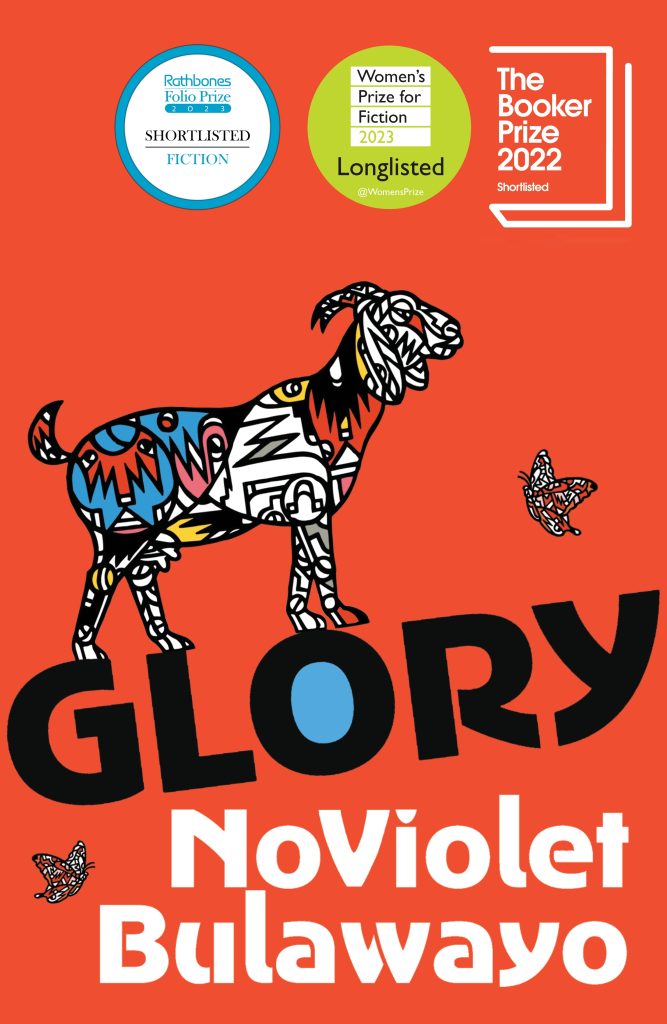

Author: Noviolet BulawayoPublisher: Vintage (part of Penguin Random House)Reviewer: Stephen Keim

Glory is set in the fictional African country of Jidada.

The action opens with a rally of the governing party in support of the Father of the Nation who has been President of Jidada for forty years and who shows no sign of retiring or resigning. The attendees of the rally know what is expected of them to support the personality cult of their president and wear Jidada Party regalia suitably embossed with the face of the president.

The members of the Seat of Power Inner Circle are in attendance at the rally and occupy chairs within the white tent set up to protect them from the broiling sun. Among the Inner Circle sat the president’s female partner, Doctor Sweet Mother of the nation. The title reflected Sweet Mother’s award of a Ph. D. awarded, as the reader finds out later, in response to a phonecall demanding to know why the university had not already offered the degree in recognition of the caller’s eminent position in the nation.

The Sweet Mother, along with the Father of the Nation and the Vice-President and others, get to address the rally. She uses her speech to castigate the vice-president as a forever traitor to the revolution and the nation. This augurs badly for the vice-president since attacks by Dr Sweet Mother on other heroes of the party and the nation have led, in short order, to their removal from the inner circle and other severe detriments.

The history of Jidada echoes that of many African countries. The country had been a long term colony of a European power. A bitter war of independence had been necessary to end the imperial control of the country. Soon after the leaders of the rebellion had assumed power and commenced to rebuild the shattered former colony, a faction had unleashed a savage repression in order to seize total control of the country. Those who suffered in that repression and the massacres and the cruelties it entailed were largely of different tribal heritages to the faction which seized power. The repression did not spare those who had fought bravely in the war to end imperial control. Indeed, because of the prestige provided by their actions in the war, it was considered necessary to target and to eliminate them and many of their families and to do so with the greatest cruelty.

It is a feature of Glory that all of the characters are animals. Father of the Nation and his vice-president are horses. Dr Sweet Mother is a donkey. The security police, known as the Jidada Defenders are dogs of the most vicious kind. The obvious comparison is with George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Bulawayo has said that the comparison with Orwell’s fictional revolution was the product of conversations among the general public in the wake of the 2017 removal of Robert Mugabe as president of Zimbabwe. The resulting governance of Zimbabwe fell well short of expectations such that people began to say that Zimbabwe was like Animal Farm.

The effect of adopting animalification of people in Glory is a little different. Orwell characterised the tendency, in the wake of a hard fought evolution, to authoritarianism by making the pigs the new ruling faction. It was also the pigs who invented the propaganda to justify the new tendencies giving rise to such enduring terminology such as “newspeak”. Apart from the dogs’ aptitude for violence in the creation of governing order, the actions and personalities of actors in the novel is not generally attributable to what species of animal they are. Indeed, even the tribalism which leads to factionalism is not species based.

The action in Glory is not precisely dated. Past events are however described as occurring in specific years. The political rally with which the novel opens may be seen, by reference to those past events, as occurring in about 2020 or a little earlier. This gives a curious feel to things. Animal Farm, published in 1945, now feels a very old book. A new Animal Farm, set in contemporary times, seems a little askew, in that even Jidadan animals have access to the internet and are strong fans of every kind of social media. One could never imagine Orwell’s animals living in the age of the internet.

Glory is written with a Zimbabwean creole flavour to the English. Frequently, the narration interpolates “tholokuthi” into a phrase or sentence. The context suggests that the word works as a kind of exclamation indicator. Other reviews suggest that its meaning is “only to discover”. “Jidada” is frequently referred to as “Jidada with a da and another da” as if to emphathise the wonderful uniqueness of this country. On occasion, happenings will be disclosed by the narration with the introduction that even the stones and sticks were aware of the particular fact being disclosed. The wonderful complexly African names of every character involved also gives a very localised flavour to the language of the novel.

The opening description of the rally and its protagonists reveals to the reader the sorry pass to which Jidada has come. Soon, however, Dr Sweet Mother is revealed to have overplayed her cards and a palace coup is effected to remove the president and the first femal as is Dr Sweet Mother’s other title. The coup is effected by the dogs who are the Generals who lead and control the Defenders. The vice president is made the acting president, one suspects, as a figurehead, and he is marketed by a new personality cult as the Saviour of the Nation. It is the former Sweet Mother who is portrayed as the chief animal from whom the nation needed to be saved.

The coup is marketed as the New Dispensation and the world at large and the people of Jidada are given to believe that a new liberality, an end to corruption and free, fair and credible elections are about to occur.

At this point, the focus of the third person omniscient narration turns from the national stage and the world through powerful people to a young female goat who is returning to her home village after a self-imposed exile. This is Destiny and the past and the present and the emerging future tend to be observed through the eyes of Destiny, her mother, their neighbours and the animals of the village and the ordinary animals of Jidada. These include cats, ducks, geese, cows and, as we know from Destiny’s presence in the action, goats. At times, the narration turns into the second person plural as if the whole village and the animals of Jidada are confessing what they should have known or should have done differently in the past.

With the focus on the animals of the village and on Destiny and her family, in particular, the reader’s empathy is engaged as one is forced to endure the horror and trauma and violence of the oppression that occurred forty years before and which has been repeated, numerous times in Jidada’s history since then.

The New Dispensation, of course, turns out to be a fraud and the free, fair and credible elections, against all belief, tholokuthi, return the Saviour of the Nation and the Jidada Party to power.

The restraint shown by the government while it was selling its new image and, at the same time, stealing the election, is not necessary anymore and a new round of oppressive violence is unleashed.

This is the age of the internet, however, and dissent continues to circulate, online. This is described in the text as Jidada being two countries: that which existed on the internet and the Country Country in which one acted much more circumspectly. Despite the dangers posed by the Defenders, the online discussions begin to leak into the other Jidada.

While these events are unfolding, Destiny is finding out who she is and the history of her family of whom she, previously, had no knowledge. She and her mother, also, bridge the gaps in knowledge and experience which had prevented them from communicating in any meaningful way. And she is prepared and empowered to take part in the events which are unfolding.

Glory is about Zimbabwe. The author acknowledges as much. The proposition is supported by Destiny’s visit to the abandoned village in which, forty years earlier, most of her family had been murdered which is named Bulawayo although this village is said to be distinct from the city of the same name of which it forms part.

But Glory is about much more than one country. It is about the emergence of authoritarianism and oppression in all countries. It is about why revolutions lose their ideals and fail and have to continue as a parody of what they promised to deliver. It is also about what can make revolutions succeed when all power and the ability to use force seems to be centred in one group of animals. It highlights the ultimate fact that even the most powerful and ruthless animals depend on the cooperation of other animals and that ruling others by force, at the end of the day, requires a modicum of consent by those who are ruled.

For these reasons, the novel is worthy of Animal Farm. Just as with Animal Farm, Glory is not about a single set of events. Just as with Animal Farm, the lessons of Glory are universal, not particular.