FEATURE ARTICLE -

Book Reviews, Issue 39: Dec 2009

By Ronald Wright1

Published by Text Publishing, Melbourne, Australia2

Reviewed by Stephen Keim

After intending to do so for some time, I recently read Jared Diamond’s Collapse. Explaining to a colleague the subject matter and themes of Collapse, I was told that I really must read A Short History of Progress. I followed my colleague’s advice and soon found that he was right. One cannot talk about Collapse without considering A Short History. One cannot discuss A Short History without, immediately, making comparisons with Collapse.

Both books discuss the failure of various past civilisations. And both books drew lessons from those failures which raise concerns about the potential longevity of the globalised civilisation that currently fills the Earth to bursting. Despite this similarity, the books are extremely different and the authors bring different skills and different methods to their respective works.

Ronald Wright delivered what was to be published as A Short History of Progress as the Massey Lectures in 2004.3 The manuscript for the lectures was published by Text in the same year. Both authors were, possibly, working up what became their respective books without knowing that the other was pursuing a very similar theme.

Collapse is a huge book, over 600 pages long. Jared Diamond tells aspects of his life story while presenting detailed case studies of Easter Island; Norse Greenland and several other civilisations, some of which did indeed result in complete collapse and some of which have, against the odds, survived to modern times. He draws his conclusions from the case studies in considerable detail and he repeats his key points several times to make sure that his readers have joined all the dots.

A Short History is indeed short. It contains less than 200 pages. Whereas Jared Diamond has been both a Professor of Physiology and a distinguished ecologist before turning his attention to the big pictures that emerge from the canvases of history in his latest career as a Professor of Geography, Ronald Wright is, first and foremost, a professional archaeologist and historian, and he weaves his way from Neolithic farmer villages to the projected population of the world in 2050 with an ease, confidence and lightness of someone who is completely at home with the subjects of the great complexity that the two disciplines offer.

Although Wright and Diamond may not have been aware that the other was working on a similar theme at the same time, the two writers were, however, not completely unaware of the existence and work of the other. My copy of A Short History has Robyn Williams, brilliant host of the Science Show on ABC Radio for more than three decades, saying: “Rarely have I read a book that is so gripping, so immediate and so important to our times. Jared Diamond will be jealous.” (Emphasis added.) And at footnote 28 in chapter III of A Short History, Wright says of Diamond’s earlier work, Guns, Germs and Steel, that it is “informative on germs but should not be relied upon for archaeological and historical data or interpretation.” He goes on to give examples.

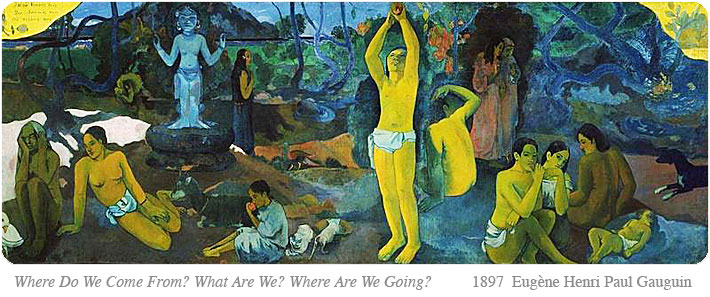

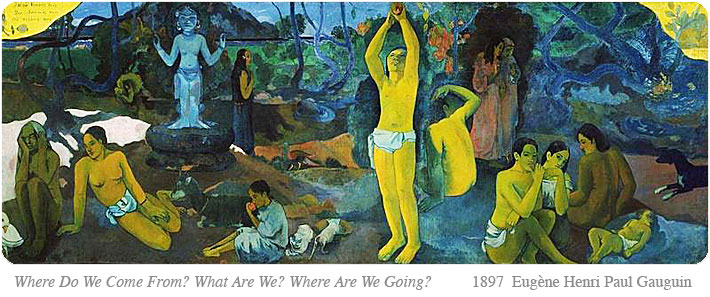

Wright takes as his theme, a famous painting of Paul Gauguin and the three questions that form its title. Translated into English, they read: “From where have we come? Who are we? And to where are we going?” He suggests that it is possible to answer the third question by considering the first two. The need to answer the third question, he suggests, is urgent for we must make the necessary adjustments to ensure that we are headed towards safety and not a disastrous shipwreck. This is the repeated lesson of the past but, since the vessel we are travelling in (essentially, the whole planet) is the last available, the lesson has taken on particular importance. A Short History really is a short history of progress and not simply a didactic tale. However, the lessons are so infused in every part of the past that that the teaching of moral lessons cannot be avoided.

In discussing the lessons from the past, Wright uses the concept of a progress trap. The hunter and gatherer who succeeds in killing two mammoths rather than one may live more luxuriously than his predecessor. However, learning to kill 200 mammoths at once may lead to some short term feasting but disaster and starvation in the medium and long term.4 The progress trap has, says Wright, reoccurred frequently through history such that many very successful civilisations have formed a prelude to their own disappearance as the supply of resources on which they depended was unable to be sustained.

In considering human progress, it is remarkable to note that most of what, from today’s perspective, we would attach significance to is so recent. The Palaeolithic Era or Old Stone Age lasted from when tool making hominids appeared, approximately 3 million years ago to the melting of the glaciers of the last Ice Age, about 12,000 years ago, more than 99.5% of human existence. Civilisation, with its layered societal structure and large buildings and other labour intensive infrastructure, is even more recent with the earliest examples being Sumer in Iraq and Ancient Egyptian society both of which emerged just five thousand years ago.

Any concerns about the short period of time during which civilisation has existed are only exacerbated when climate history is taken into account. Agriculture and complex society have only developed during the last 10,000 years. Palaeo-climate studies show that this has been an unusually stable period for the world’s climate. Wright draws a causal conclusion from the correlation. If our form of living, which now fills the whole world, is dependant upon a stable climate, then it is particularly worrying that that stability appears threatened by our actions of the last 300 years.

A Short History is fascinating for the way in which Wright traces the pattern of particular developments as they occurred across the world. While 8-10 thousand years ago, the Middle East was developing societies based on the growing of wheat and barley, in China, rice and millet were coming into domestic production and, in Mexico and environs, a host of staples, including maize, beans, squash and tomatoes were providing the basis for new civilisations to emerge. In the same way at about the same time, while sheep and goats were being domesticated in the Middle East, primitive llama and alpaca were being domesticated in Peru. Wright rejects the Victorian era approach of classifying by changes in the materials used to make particular tools or even by reference to the type of tools. Societies made progress which was relevant to their circumstances and, frequently, large populations and complex societies could be supported in one area of the world without using inventions that had been of great importance elsewhere.

Like Diamond, Wright uses specific case studies although he spends less time on them. Indeed, he uses a number of the same examples, including Easter Island, Sumer and the Maya peoples of Central America. He uses Ancient Rome, China and Egypt. He notes that, while some societies disappeared completely, others merely entered massive declines leaving some descendants to battle on to modern times and some, like China and Egypt, for identifiable reasons, lasted at their peaks for longer periods but not without a number of major crises.

I am indebted to Wright for a critical insight into the causes of the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe. While Wright does not discount the likelihood that such transformation would have occurred at some time without Columbus’ serendipitous landfall in the Caribbean, he attributes the fact that it occurred when it did to European exploitation of Columbus’ discovery of two new continents and the civilisations and resources which they contained.

The contributions are many layered. The precious metals carried back by Spanish galleons triggered a Keynesian investment surge that allowed technological advances which may not have, otherwise, ensued for centuries. The wide acres of North and South America became available to excess European populations after disease had destroyed the Native populations’ ability to resist. And new crops such as maize, turkey, beans, squash, pumpkin and potatoes allowed European subsistence farmers (on both sides of the Atlantic) to produce unprecedented food surpluses freeing more and more workers for the new factories. As Wright points out, the period of slightly over 500 years has allowed the Italians to build a culture around tomatoes; the Swiss and Belgians around chocolate; and the Irish and English around potatoes: all crops unknown in the Old World prior to 1492.

Wright takes the title of his final chapter, The Rebellion of the Tools, from an epic story from the Maya civilisation of Meso-America, a story in which farm and household implements come to life and wreak revenge on the humans who have subjected them to the pains of the grinding wheel and the pots and pans seek similar revenge for being subjected to the pain of fire heat. He explores two creeping causes of disaster for successful societies: the problem of increased food production leading to increased population and the need for yet more food production and the tendency for inequality to develop as the society grows increasingly hierarchical. Both tendencies lead to pressure upon the ecology on which the society depends and to want and starvation for the mass of the population, ultimately, leading to social instability.

And, so, the lessons of the study of human progress and the punctuating incidents of societal collapse result in an intensely political set of conclusions. Wright laments, for the survival of civilisation, the abandonment of the attempts to encourage equality of opportunity brought about by the John Maynard Keynes influenced Bretton Woods Agreements of 1944. He laments the trickle down policies of the far Right which have dominated world policy making since the 1970s. He cites the statistic that the three richest individuals, in 2000, all Americans, had a combined wealth greater than the world’s poorest forty-eight nation States.

A Short History is not without hope but hope is accompanied by a piercing sense of urgency. Even as he points out that the extra 3 billion people who will be alive in 2050 can be fed by raising less meat and by spreading the food around and by helping India and China industrialise without the mistakes of the past, Wright emphasises, with searing rhetoric, the senselessness of most present policies: “But instead we have excluded environmental agreements from trade agreements. Like sex tourists with unlawful lusts, we do our dirtiest work among the poor.”

A Short History is a masterful work. It is an antidote for many of the shallow exchanges that pass for a debate on the development of climate change policy in 2009. It is particularly noteworthy that, some four years before the Global Financial Collapse that made everyone a Keynesian, Wright’s Massey lectures identified the moral emptiness and ecological bankruptcy at the heart of trickle down, supply side economic policies.

Jared Diamond need not be jealous for Collapse is also a fine work. As readers and citizens of the twenty-first century, we should be grateful that two such fine writers, in their very different ways, have taken such trouble to explain so carefully the lessons of the past which should guide us away from our present precipitous course.

A Short History ends with a comparison of our present position with that of the fateful Easter Islanders who, while a few trees remained standing, continued to chop them down in order to cart and erect the Moai, giant statues made to honour their ancestors. Five years have passed … and many fewer trees remain standing in our giant Easter Island analogue. Shall we continue carving at the Moai quarry? Shall we continue to wield the axe?

Stephen Keim SC

Footnotes

- Wright’s personal web site listing his books is at http://www.ronaldwright.com. See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_Wright.

- See http://textpublishing.com.au.

- The Massey lectures are named for Vincent Massey, a former Governor-General of Canada. They were established in 1961.

- In fact, as Wright describes, the hunters of the Upper Palaeolithic became so successful (and so numerous) that the invention of farming became necessary as the numbers of available game became severely diminished. The progress trap was, indeed, sprung and its implications only avoided by adopting a new lifestyle.