Introduction

The decision to celebrate Human Rights Day on 10 December was made by the United Nations General Assembly in resolution 423(V) on 4 December 1950. The resolution invited all member states and interested organisations to celebrate the day in whatever way they saw fit. Celebrations have been many and various. The best celebration of which I am aware is that of former Chilean general, dictator and purveyor of crimes against humanity, Augusto Pinochet, who chose to leave this realm and his mortal coil on human rights day, 10 December 2006.

The date chosen by the General Assembly in 1950 was a no brainer. Only two years before, a long and tortuous process reached its climax with the passage, a few minutes before midnight, on 10 December 1948, at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, across the Seine from the Tour Eiffel, when what had become known as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“the UDHR”) was adopted by the General Assembly.

The Road to the Universal Declaration

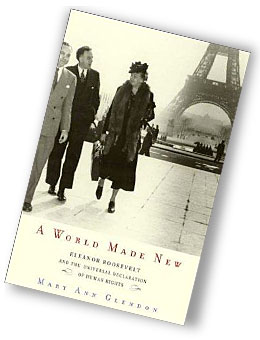

A World Made New appears to have been written as a project for the fiftieth anniversary of the UDHR but was not published until 2001. The influence of the UDHR may be seen in the currency obtained by human rights values in the sixty-three years since 1948. Even those who are famous for destroying human rights tend to defend themselves by denying the evidence and acknowledging the validity of human rights values as appropriate standards against which one should be judged. It is only when the evidence becomes undeniable that the UDHR is attacked as representing western values as was the case, for example, with Singaporean, Lee Kuan Yew.

A World Made New is an example of the proposition that history need not be about politicians or generals to be significant to us. Conveniently, Professor Glendon’s book is about a great person, in Mrs Roosevelt, as well as about a document and the ideas that it captured and gave to the world.

Most observers would endorse the strong association between the person and the document and also with the ideas. Mrs Roosevelt always regarded her association with the negotiation and adoption of the UDHR as her greatest public achievement. Many people have expressed the view that, without her involvement, the turbulent winds of a developing Cold War would have overcome the goodwill of the post war period making the achievement of the Declaration impossible at least for several decades.

Long and Winding Road

A World Made New charts the exceedingly difficult path traversed by those who negotiated the UDHR. It also details the contributions of various delegates from a range of the world’s nations and cultures who were part of that exhaustive process.

A key early step occurred when a group of American human rights NGOs, including the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, religious tolerance groups, and the peak union body met with the US secretary of state, Edward Stettinius, in May 1945. Apparently as a result of the urgings of that group, the secretary of state announced that the US would reverse its opposition to the establishment of a permanent commission on Human Rights as part of the yet to be formed United Nations. In retrospect, that made the UDHR possible.

Over the advice of foreign policy professionals, President Truman resolved to appoint Mrs Roosevelt, the widow of his predecessor, as part of the United States delegation to the first meeting of the recently formed United Nations in London commencing on 10 January 1946. She had made sufficient impression on the Atlantic voyage that Senator Vandenberg, the leader of the delegation, asked her to be the US representative on the (less important) third committee on social, humanitarian and cultural affairs.

Mrs Roosevelt impressed both her masters and her colleagues from other countries. Shortly after the London meeting, she was asked to be part of a nuclear committee to derive priorities for the yet to be formed Human Rights Commission. She was elected Chair of that committee which recommended developing a Bill of Human Rights as the major priority for the new Commission. In June 1946, Mrs Roosevelt was appointed Chair of the Human Rights Commission of the United Nations.

The Human Rights Commission met at the UN’s temporary home in an old gyroscope factory at Lake Success at the northern end of Long Island, New York on 27 January 1947. In the twenty months that followed, the nationalist Chinese were being thrust from power in China; the Berlin blockade and airlift was taking place; the partition of Palestine had occurred with resultant war and creation of refugees; and the scheduled free elections on the Korean peninsula were not taking place, setting the scene for the subsequent war. This was an extraordinarily difficult period during which to negotiate a foundation document on human rights. It could only be achieved because of the presence of a person with the patience, respect and leadership qualities of Roosevelt. It is to our benefit that she was there.

As a result of the January, 1947 meeting, the director of the secretariat to the Commission, Canadian academic lawyer, John Peters Humphrey was asked to prepare a draft Bill. The 48 article document, prepared with the help of the secretariat and presented in early June 1947, was described by Humphrey as containing “every conceivable right” which the Commission might want to discuss. Deservedly, Humphrey is acknowledged as the author of the first draft of the UDHR.

After briefly discussing the Humphrey draft, the Commission’s drafting committee referred the draft to one of their number, Rene Cassin. Cassin was a proud French, Jewish, internationalist, also with a legal academic background, who had served during the war as De Gaulle’s principal constitutional lawyer. His instructions included a direction to give philosophical direction to Humphrey’s collection of rights. Cassin succeeded admirably, breaking the articles into themed chapters with headings and adding a preamble which provided the justification for having an international Bill of Rights. Cassin is recognised with Humphrey as one of the two principal authors of the UDHR.

The draft went through weeks of discussions at a time, either before the Human Rights Commission or a drafting committee thereof, in June 1947; November 1947; May 1948; and May/June 1948 when the much discussed and somewhat changed document was forwarded to the Economic and Social Committee of the United Nations.

A salutary contribution was made by Hansa Mehta, a female delegate from India and a long term fighter for Indian independence and for women’s rights. Mrs Mehta had served as one of two advisers on the drafting of the rights provisions in the Indian Constitution. At home, she was battling against many traditional practices that restricted the rights of women including purdah; child marriage; polygamy and restrictions on marriage between different castes. It was Mrs Mehta who, among other important contributions, insisted on and succeeded in changing the references to “all men” in the first article to its more inclusive reference to “all human beings” and giving the same inclusive feel to “everyone” and “no one” where they appeared in future articles. This made the UDHR well ahead of its time and gives it its inclusive feel from the very first line.

Another philosopher and professor, but also playwright, Peng Chun Chang, was part of the drafting process from the beginning. He saw his country betrayed by a corrupt government and wrested from him by a Communist revolution even as the debates were going on. Notwithstanding, he continued to contribute, explain and defend the Declaration through many exhausting and exhaustive debates. Early on in the process, he insisted that the document should have a preamble and that it should stress the dignity of human beings. He also contributed the traditional Chinese concept translated literally as “two-man mindedness” and indicating a consciousness of the feelings and interests of others. It is found inadequately translated as “conscience” in article 1 in the phrase “[human beings] are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood”. His influence, however, appears in every line of the Declaration.

A young Lebanese Christian law and philosophy professor, Charles Malik, was rapporteur of the Human Rights Commission and was subsequently elected chair of Economic and Social Committee and the Third Committee, the two major committees through which the Declaration had to proceed to arrive at the General Assembly. His patient and then firm chairmanship ensured that the Declaration arrived on time and intact, despite every delegate from every interested company having had full and repeated opportunity to comment, change and contribute to the document. Among his many contributions, however, is his redraft of the preamble at the request of Mrs Roosevelt over a weekend in mid-June 1948.

At the time, as a Christian Arab from the then tiny and multi-cultural state of Lebanon, Malik was rushing from meeting to meeting on the Palestinian crisis and articulating both the Arab cause and the need for tolerance and decency. His singular contribution is the opening paragraph of the preamble which anchors the Declaration in a belief in the inherent dignity and equality of all human beings. With further changes from the exhaustive discussions that followed, the paragraph leads off, beautifully, and gives the document its characteristic basis: “Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world”.

The discussions in the Third Committee ran from 28 September to 7 December 1948. Article 1 was debated for almost a week. Every article was debated at length. But the structure and key aspects of the text survived at least unscathed and with some improvements.

Under the Chairmanship of Australia’s HV Evatt, the debate in the General Assembly was just a few days, commencing on the evening of 9 December and the votes were counted just before midnight on the following day. Thirty-four delegates had spoken. The vote was on a vote of 48 votes in favour, 8 abstentions (the Soviet bloc and South Africa and Saudi Arabia) and none against.

Dr. Evatt said: “It is particularly fitting that there should be present on this occasion the person who, with the assistance of many others, has played a leading role in the work, a person who has risen to greater heights than even so great a name – Mrs Roosevelt, the representative of the United States of America”. The General Assembly gave her a long standing ovation.

The Heritage

The influence of the Universal Declaration is such that we read the words of the document (and the Conventions it has spawned) and we think them a little trite and certainly obvious. It is easy to fail to understand the massive achievement it was to state, in a preamble and just thirty articles, a set of values on which so much of the world can agree even those who are smashing those values by their actions.

When the Declaration was being negotiated, the very idea of values with sufficient universality to be adopted was hotly disputed. That the Declaration was adopted and that we now see its provisions as trite may be one of its greatest achievements. We suffer a great loss, however, if we do not appreciate the difficulty of that achievement at that time. We also suffer a loss if we fail to appreciate the beauty of the language put together so ably by Humphrey, Cassin, Chang, Mehta, and the others who contributed.

Professor Glendon’s A World Made New is a fascinating tracking of the path that led to the UDHR. A World Made New is also valuable for re-introducing us to the UDHR: “a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations”.

Stephen Keim

Footnotes

- Ms. Glendon is the Learned Hand Professor of Law at Harvard University. She served as United States Ambassador to the Holy See under the Administration of George W Bush.