FEATURE ARTICLE -

Book Reviews, Issue 51: Aug 2011

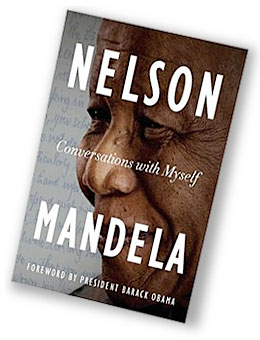

Conversations with Myself is the result of a project by the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue. The Centre is run by the Nelson Mandela Foundation and its role is to act as an archive of the most historic documents relating to the great man. However, the web site states that the Centre is not just about preserving his memory but is about contributing to a just society by promoting Mandela’s vision and values.

Conversations with Myself is, in effect, a collected writings of Mandela. Mr. Mandela approved of the project but stated that he did not wish to have an active involvement therein.

The introduction by Verne Harris, the leader of the Project explains the sources utilised for the collection. There proved to be four main sources. The first was Mandela’s prison letters. Mandela kept copies of the letters he wrote from prison. This proved to be good judgment since many of his letters were not posted by the authorities and have been lost although a few have turned up from state archives.

The second main source of material comprises two groups of recorded conversations. The first set consists of sixty hours with Richard Stengel when the two men were working on Long Walk to Freedom. The second group are conversations with his old ANC and prison colleague, Ahmed Kathrada, for the related purpose of reviewing early drafts both of the Long Walk to Freedom as well as Anthony Sampson’s authorised biography of Mandela.

The third source is Mandela’s note books. Mandela has, from before his prison days, been a great keeper of notebooks. The books provide access to his private thoughts and do so with a great degree of contemporaneity and currency.

The fourth source was an unpublished draft for a sequel to Long Walk to Freedom.

It is not surprising then that Conversations With Myself provides an intimate picture of Nelson Mandela as the human being that became the great man in a way that Long Walk to Freedom did not seek to do.

In his introduction to Conversations With Myself, President Obama describes this phenomenon in the following terms:

“… Nelson Mandela reminds us that he has not been a perfect man. Like all of us, he has his flaws. But it is precisely those imperfections that should inspire each and every one of us. For, if we are honest with ourselves, we all know that we all face struggles that are large and small … The story that is … told by Mandela’s life is not one of infallible human beings and inevitable triumph.”

Conversations With Myself reminds (or tells for the first time) the reader of the extraordinary events of Mr. Mandela’s life. It is easy to forget that the Rivonia trial, which resulted in the nearly thirty years of imprisonment, was for treason which carried the death penalty. Each of the defendants who was convicted fully expected to be sentenced to die, both during the trial and during the overnight wait after the adverse verdict had been returned. Mandela’s famous “I am prepared to die” speech was delivered fully expecting that he would be called on to do so. Conversations With Myself carries an image of the notes for that speech, an impressively brief five points on half a page of paper which gave rise to several thousand words of carefully articulated rhetoric.

The hardness of prison life is conveyed in the book but does not receive a great deal of emphasis in the Conversations. It is clear that Mandela and his colleagues continued to organise and plan within prison and everything was done with solidarity for one another. What nearly destroyed Mandela, however, was the death of his mother (without the ability to attend to his filial duties of being at her bedside and attending her funeral) followed closely by the death of his oldest son in a motor vehicle accident. The pain of these two events comes through in letters written to members of his family and in letters written to prison authorities requesting permission to attend the funerals of two such close relatives. The pain was no less for the fact, acknowledged by Mandela in his letters, that he had sacrificed so much of family life for himself and other family members by choosing to commit his life so closely to the cause.

His letters to prison authorities are inspiring, especially, for those among us who have written with little if any hope to prison authorities and bureaucrats of similar ilk. His letter to the Justice Minister seeking that he and his colleagues be treated as political prisoners is notable for the confidence with which it was written as much as for the temerity to write it in the first place. The fact that, ultimately, Mandela spent the final years of his imprisonment as a negotiator and then essentially a president in waiting adds to the general wonderment that accompanies the letter.

Whenever he wrote to authorities, Mandela displayed the talent for advocacy that has characterised his years as politician and senior statesman. When writing to high officials of the Nationalist government, Mandela did not write of his heroes but of Afrikaans heroes who had been prepared to and did die at the hands of their British overlords. It was with the struggles of these heroes that he compared his own struggle and that of his comrades both in and out of prison.

The respect which Mandela earned among prison authorities and, ultimately, government officials is remarkable but understandable in the light of the principled strength which emerges from Conversations With Myself. Ultimately, it is not surprising that President FW de Klerk chose Mandela as the conduit through which to achieve the unthinkable, a non-racist South Africa.

It is easy, in retrospect, however, to skip over how problematic and difficult the change over period was for a man who had been sidelined from politics in the orthodox sense by his prison sentence. It is also easy to underestimate the obstacles. Conversations With Myself reminds the reader that, even, and especially, after Mandela’s release, a third force consisting of right wing elements with security and police force involvement sought to derail the peace process by killing large numbers of black South Africans. Characteristically, Mandela sought to and did deal with the problem by speaking directly to those who, he thought, were leaders of the movement causing the problem. He spoke in his strong, direct, principled and ultimately uncompromising manner. He triumphed.

I never got around to reading Long Walk to Freedom despite the fact that everybody I know in the world carried it with and lapped it up. For those of you who did, Conversations With Myself is probably essential reading in that it will reacquaint you, and in a more intimate way, with your great hero. For those of us who did not, Conversations With Myself is still a must read. The lapse of two decades since those heady days of transformation in the early nineties make this an appropriate time to reflect upon the nonagenarian who dominated them and did so much to bring them about.