FEATURE ARTICLE -

Book Reviews, Issue 57: Oct 2012

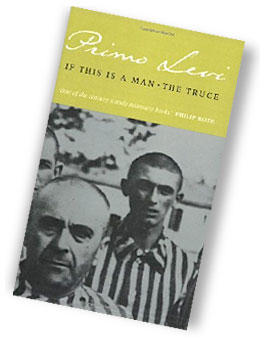

Over two decades ago, I read Primo Levi’s collection of short stories describing adventures with different elements published under the collective title: The Periodic Table. I found the short stories interesting, poignant and entertaining. When I started reading The Periodic Table, I may not have known that Primo Levi was an Italian Jew from the Milan area who survived well over a year in an Auschwitz concentration camp and who wrote a famous account of that experience.

I was aware, however, before I finished that volume and, in fact, the very Vintage edition I read for this review has been on the shelves at home since I gave it to my daughter, Anna, for the Christmas of 1996. A form of moral cowardice had kept me from opening and reading the volume until a few weeks ago when Mark, the architect and our friend and next door neighbour, nominated Primo Levi’s classic work for Blokes’ Book Club.Now, there was no avoiding the experience of coming to terms with the experiences set down therein.

As he indicates in his afterword, written well after both novels reviewed here, Primo Levi restricted both novels to a witness account. He puts down that which he experienced and witnessed. His account is not the result of extensive research. It does not repeat what other authors have found through interviews or by trawling through the records left by the Germans. He was keen also to be a credible witness. He makes no emotional appeals. He does not set down extensive condemnations. Primo Levi records what he can remember of actual events and he lets the events speak for themselves and leaves judgment to the reader.

If This is a Man is the account of the author’s experience from when he was captured trying to be a resistance fighter in the mountains of north Italy; his transfer as part of 650 Italian Jews from the Fossoli detention camp near Modena to Auschwitz in Poland; and his experiences until the end of the ten days between the German abandonment of the work camps of and around Auschwitz and the sick prisoners they left behind and when the advancing Russian soldiers came to the rescue of those same detainees.

The Truce was written more than a decade after If This is a Man. It is the story of the strange life that followed the arrival of the Russian soldiers. It took nine months of travel along a roundabout route with long stays at various staging posts before the author arrived at his home in Turin on 19 October 1945. It was an enjoyable, liberating and frustrating time. At the end of this, the second of the two books, that the reader finds out why it is called The Truce. It was only when he arrived home that the author had to face re-adjustment to living among people who had not shared his privations and the horror of the camps. When he arrived home, Primo Levi had to face the meaning of what he had experienced and survived. The preceding nine months had therefore been a period of truce.

I have read other accounts by victims of inhuman conduct. Brian Keenan’s An Evil Cradling, an account of four years of captivity in the late 1980s after having been kidnapped from his teaching job in Beirut was full of horrific experiences difficult to contemplate or comprehend. David Hicks’ Guantanamo: My Journey is marked not only by its descriptions of torture and beatings and unbearable confinement and living conditions but also the increasing despair of months stretching into years of dashed hopes that “all this will get sorted out”.

There are limits, however, to what a book can convey. The reader is appalled for the period of the reading. Then the book is put down and normal life and its comparatively minor pleasures and stresses take over our consciousness and the author’s experiences fade from our minds. Later that day or a few days later, we return to our place in the book. But the pages already read have been left behind and we move forward through another set of experiences. Then normal life intervenes again. No matter how well the experiences are narrated, the reader’s experience is worlds away from those experiences which the author is recalling.

And so it is with If This is a Man. Primo Levi’s writing is more powerful as a result of its understatement. It conveys a life of freezing cold, crowding, exhausting work, filth and starvation that would strip the strongest among us of any will to survive. And yet, despite the horror, it is just a book and it is normal life that demands our attention, the moment the bookmark is replaced and the book is put down.

Nonetheless, If This is a Man provides unforgettable images and raises haunting questions that stay with the reader and raise themselves despite the best efforts of normal life to block them out. The very arrival at Auschwitz after a long journey in closed rail wagons is one of those images. The questions of the SS officers are low key and unthreatening. The answers to questions of the arrivals are almost reassuring. They do intervene on one who delays too long in farewelling his fiancée with a blow that knocks him to the ground. No indication is given that the questions identify those can do useful work for the Third Reich from those,the young, the old and the sick,who are destined for gas chambers and cremation ovens, immediately.Only 125 from the group of Italian Jews who arrived on that train went into the camp and more than 500 perished immediately.

The initiation into the camp is equally as confronting. Stripped of their clothes and shoes in freezing cold draughty buildings, afflicted by thirst from several days without water, heads shaven, devoid of any information that made sense and waiting for hours that stretched into days, madness and despair must have been ever close at hand.

Life became no easier when the initiation process was complete. The slide to death by exhaustion or sickness leading to selection for the gas chambers threatened at every point. Levi provides an extended metaphor through Null Achtzehn, a member of Levi’s work team who has forgotten his name and is known to himself and others only by the last three letters of the number tattooed upon his forearm: 018, in German, Null Achtzehn. Null Achtzehn drops the heavy bar being carried and it strikes Levi on the foot. Like many other people whose story is briefly recounted, Null Achtzehn disappears from the narrative and is not heard of again. There are many bit players in a narrative set in a concentration camp. They disappear and no one sees them go.

Though there is surprisingly little condemnation in If This is a Man and the facts speak for themselves, there is reflection. Levi reflects upon the dehumanizing purpose of the camps. He also reflects upon the methods used to survive. In a chapter called The Drowned and the Saved, Levi discusses the willingness of some among the oppressed to take positions of privilege earning an easier life and better chance of survival at the cost of inflicting further pain and oppression upon those they are asked to supervise. There is no shortage of volunteers and so there is added incentive to inflict greater cruelty upon one’s fellows. Like everything else he describes, Levi is not surprised by the willingness of the oppressors to use these methods of ensuring the effectiveness of their rule or the ease with which they find volunteers to take the roles they offer. The behaviour fascinates him, however, and The Drowned and the Saved is the title of a book published in the mid-fifties, some years after If This is a Man.

Luck must be important to survive in a place where death stalks down every corridor, every minute of every day. Loss of motivation, however, is a recipe for a certain and rapid death. The determination to survive and be a witness was, undoubtedly, Levi’s principal motivation. Coincidentally, Primo Levi also happened to be a brilliant writer.

The result is a book that, nearly seventy years after the events it describes,remains a book that is a “must read” on more and more serious levels than that phrase is normally used.

Ironically, Book Club Night was the same night as State of Origin III. We arrived early and we discussed If This is a Man at some length. David, newly a barrister, indicated the beautiful writing of Primo Levi by describing the shame he felt at looking forward to reading more about life in the camp. Then normal life intervened. It was time to serve the pizzas and watch the game.

For the record, Queensland won.

Stephen Keim