FEATURE ARTICLE -

Book Reviews, Issue 73: July 2015

This memoir commences at the end of the narrative, on a beautiful Cuban evening at Guantanamo, in May 2007. The author stands to one side, as it were, and watches the process by which his client of almost four years is placed on a plane to be repatriated to Australia.

A symptomatic expression of the difference between us and them occurs. David Hicks shuffles toward the stairs of the plane. The Australian police escort ask the US security escort to remove the shackles. David Hicks walks up the plane’s stairs into 9 months of Australian prison custody. But does so without having to shuffle.

Notwithstanding this display of moral superiority on the part of Australia over their long term ally, the United States, Dan Mori’s memoir [1] provides supporters of the rule of law and due process in both countries to squirm with shame.

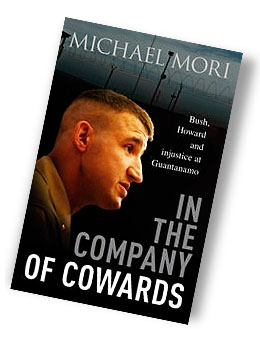

In the Company of Cowards is Mori’s account of his experience in representing David Hicks in the Military Commissions system set up by George Bush and Donald Rumsfeld to try prisoners swept up from the battle fields of Afghanistan. David Hicks has written Guantanamo: My Journey , his own memoir of his experience of being treated among “the worst of the worst” in the worldview created by the Rumsfeld/Bush/Cheney propaganda machines.

As Mori explicitly says, In the Company of Cowards is not an attempt to tell David Hicks’ story. I pointed out in my review of Guantanamo: My Journey that many of the matters narrated by Hicks, as based on his own recollection, are supported by third party independent sources. And the investigative processes undertaken by Mori as David Hicks’ lawyer also went a long way to confirming David Hicks’ narrative of how he came to be a United States captive.

One of the many tasks that Mori had to undertake, with a paucity of available resources, was to check the client’s instructions and to find the witnesses that those instructions indicated should exist.

Two of the most interesting chapters in In the Company of Cowards concern the results of those endeavours, particularly, of Mori’s travels to Pristina, the capital of Kosovo and to Kunduz in northern Afghanistan.

The interviews in Kosovo kyboshed one allegation on the prosecution’s list of allegations. The witnesses when they were located confirmed that Hicks had never fought in Kosovo. He had done nothing more than complete basic training. They also confirmed that the famous photograph used by Australian media outlets to portray Hicks as a dangerous fighter was a cut down shot of a photograph of a group of trainees with an unloaded weapon shown to the trainees on their first day of training.

Even more important was the evidence gathered in Kunduz. Quite unprompted, the resident who had protected Hicks from immediate arrest by Northern Alliance fighters and allowed him to stay in his home indicated, by grabbing Mori’s own cammies (or camouflage uniform) that Hicks had been wearing a proper military uniform which identified him as soldier. This confirmed as baseless the key assumption on which the charges against Hicks had been framed, namely, that Hicks was an unlawful combatant because he did not wear regular uniforms which identified him as a member of the Taliban fighting units. Those fighting units were, of course, at the relevant time, the official army of the government of Afghanistan.

As Mori also pointed out, in the context of an aiding the enemy charge against David Hicks, the US government had provided more than $20 million in aid to the Taliban as part of an opium eradication program making it a fairly significant aider of the same so-called enemy. Mori found even more hypocritical the fact that the government of Pakistan, the chief sponsor and supporter of the Taliban prior to 11 September 2001, was welcomed into the coalition of the willing rather than locked up at Guantanamo and charged with aiding the enemy along with the unlucky individuals who had fallen into the arms of the Northern Alliance and been sold into United States custody at $5,000 or $10,000 apiece.

David Hicks was taken prisoner by Northern Alliance fighters on 9 December 2001. He was handed over to US Special Forces for a reward on 17 December. On 11 January 2002, he was flown into Guantanamo Bay when the new accommodation for detainees was still being constructed.

Eighteen months later, in June 2003, Mori flew back from a temporary assignment on military exercises in Thailand to his main work with the Marine Corps Legal Department in Hawaii. He was told that he had been selected as a representative of the Marine Corps to assist in the defence of detainees held at the Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay. A few weeks later, Mori was told that he was likely to be detailed to the defence of David Hicks.

In the Company of Cowards is a memoir of Dan Mori’s quite lengthy brush with fame. Not every lawyer, military or otherwise, expects their next case to last for four years or to turn them into a household name in a country only previously visited by that lawyer to play the game of Rugby Union. An army Rugby tour was Dan Mori’s first reason for coming to Australia. That visit was far from his last.

Dan Mori has washed up in Australia. He lives and works (and promotes sales of In the Company of Cowards) here, now. One suspects that he loved Australia from the moment the whistle blew to start the first Rugby game. One suspects that his running battle to win the hearts and minds of the Australian people and government on behalf of his client only deepened that love. While true love does not necessarily run smooth, every step of the way, one suspects that the Dan Mori/Australia relationship will keep a head of steam for a number of decades, yet.

In the Company of Cowards is, of course, the story of a long running legal case. It is also the story of Dan Mori and how he got to the place where he was chosen to represent David Hicks and how he went about that task. It is also the story of two countries and how the rule of law and dedication to the idea of justice lost out to political expediency on many occasions.

To do all that in 285 well-spaced pages takes a lot of skill. The lawyers among us want to understand the law and the legal manoeuvring. The political fanatics among us want to understand just how scurrilous the politics became. (I confess that I am enrolled in both of these groups.) And there are (surprisingly) among us some non-nerds who just want to understand and feel the human story.

In the Company of Cowards achieves the balance. The law and the politics are unfurled and explained in sufficient detail that the narrative never becomes either simplistic or sloganistic. But the non-lawyer (or non-nerd) never feels at a disadvantage. The struggling military lawyer/narrator and his client, trapped in a prison build of equal parts of wire and concrete, on the one hand, and continuing uncertainty, on the other, never fade from view. The human story never loses its impact.

Now that Mori had an inkling that he would have a role to play, he started researching both the legal regime that the US government had been putting in place for the detainees and what was known through public channels about David Hicks, his likely client. He was appalled by the extent that Bush and Rumsfeld were overturning the legal regime of fairness and due process as it had been applied by the US military through all its engagements. However, he was just as surprised by the extent to which Australian politicians seemed to show a complete lack of concern about the unfair treatment being handed out to their own citizen.

Defence minister, Robert Hill; the Prime Minister, John Howard; and the Attorney-General, Darryl Williams, took turns in making false accusations against David Hicks and in expressing that lack of concern at the fact that he was being denied his rights under the Geneva Conventions, despite Australia’s long established adherence to the international humanitarian law codified in those documents.

Despite a delay of months before he was actually detailed as Hicks’ counsel, and so could start taking steps to represent him, Dan Mori was provided with the signed and initialled statement allegedly taken from David Hicks by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service.

Although Mori’s first reaction was that the strangeness of the language of the statement suggested that it was not voluntarily given, a more shocking realisation struck him after that. The statement did not confess to anything bad. Hicks, not even with any added creative flair from the interrogator, had not confessed to having hurt anybody. This statement, from a person who had been defamed by Australia’s and the United States’ political leaders as one of the most dangerous people alive, did not confess to anything.

When the charges against Hicks were finally received in May 2004, Mori experienced the same sense of nothingness. Reference was made to an organisation in Pakistan, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba as if the mere reference condemned David Hicks to the lower levels of Dante’s (no relation to Mori) Inferno . LET, as it was called, not only operated openly in Pakistan but was run with the support of the Pakistan government, an ally of the US and Australia in the war against terror. Reference in the same breathless tones was made to the Kosovo Liberation Front (“the KLF”) in Serbia with whom David Hicks had done some basic training. NATO had not only praised the KLF at the time. They had dropped bombs on many parts of Serbia over many weeks in order to gain a military advantage against the same Serbia for the same KLF.

Among the crimes that did not exist as part of the law of war, the document included the amusing allegation that David Hicks had engaged in surveillance of US and British embassies in Kabul. The document did not bother to mention that the embassies in Kabul had been long closed at the time of the alleged surveillance.

At their most serious, the charges alleged that Hicks had guarded a tank and engaged in small arms fire. The fraud that was being perpetrated was to suggest that, in an international conflict, where the United States has invaded another country, it is against the law of war for one side to fight. That was the mindset, the departure from legal reality, with which Mori had to contend in what was a deadly serious contest for his client.

It is not surprising that, at times, bemusement combined with horror emerges from the pages of In the Company of Cowards.

In July 2003, John Howard was forced to admit that David Hicks had not breached any Australian law. One might have thought that, out of pure fairness, Australia would, as had the United Kingdom, demand that its citizen be sent home. We did not do so. Perhaps, our politicians hoped that the US would make up a crime with which they could charge this Australian. As has since been shown to be the case, that is exactly what the US did .

When finally detailed as Hicks’ lawyer in November 2003, Mori noted that Hicks had been abandoned by his country. He notes the vagueness of the justification put forward at that time by Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, who said that he did not think that Australians would want someone who had trained with al-Qaeda going to the cinema. As Mori noted, one might expect that kind of ignorant talk from someone over a schooner in a pub but not from a minister of state whose sworn task is to uphold the law.

In January 2004, the Australian government was at it, again, defending the Bush/Rumsfeld military commission perversion of justice. Mori went public for the first time, pointing out to the media the flaws and unfairness of the system including the fact that the Commission Authority, who initiated the charges and approved the prosecution, also got to rule on applications brought by defence counsel. This time it was a new Attorney-General, Phillip Ruddock, who ran interference on behalf of the US Defence Department, saying that these criticisms was just normal defence counsel “jockeying”.

On his trip to Australia in March 2004, Mori was struck by irony as he jogged around Lake Burley Griffin. Through the early morning, autumn air, he spied the famous memorial commemorating Australians who had fought in the Spanish Civil War. (As a teenager, working in a railway labouring gang, I had been regaled, many times, by an Irish Australian workmate about his glorious experiences in that same conflict.) Mori also recalled that Australians had fought on both sides of the US Civil War . David Hicks was being persecuted by one country and abandoned by his own country because he had done exactly what many of his countrymen were honoured for. The irony may have been harder to appreciate from inside Guantanamo.

In contrast to the lack of concern from government ministers, Mori notes the assistance he received from many Australian lawyers. The Law Council, under John North, had fought for a fair system of justice for David Hicks and many other Australian legal bodies had provided their support to that campaign. This included a letter in late 2005 calling for David Hicks to be tried in a properly constituted court or returned to Australia. The Law Council went as far as to say that the Australian government’s inaction could no longer be accepted. The letter said that the government had dismissed the concerns of the legal profession and denied the application of the rule of law: a principle on which the entire legal system is based.

Even the public release of a set of emails from prosecutors involved in the Military Commissions condemning the system’s lack of competence and fairness could not shake the torpor of the Australian government. Downer fronted up again and said that, whatever the emails of the prosecutors involved in the process say, we are satisfied with the system by which David Hicks’ present and future was being determined.

In early 2006, a new commandant took up office at Guantanamo and conditions dramatically worsened including the return of David Hicks into solitary confinement including 23 hours a day confined to his cell. Mr Ruddock, still Attorney-General, said that he saw nothing wrong with the change. He had been assured that it was only because some buildings had been closed down.

Eventually, growing disquiet within the Australian public about David Hicks’ treatment was followed by an agreement by which prisoner transfer between the US Department of Defence and Australian prisons became possible. By 2006, even 67% of Liberal voters wanted David Hicks returned to Australia. John Howard admitted that he could have had David Hicks brought home but chose not to. Mori commenced a judicial review action in Australia against the government challenging Howard’s decision to keep Hicks detained in a foreign prison. The pressure on the government was being maintained.

In early 2007, Ruddock wrote an opinion piece to shore up the opinion that was steadily turning against the government. It was full of factual and legal inaccuracies. In an interview, he was unable to identify any law which David Hicks had arguably broken. After more than five years, all of the resources of the Australian Attorney-General’s Department could not find a single piece of David Hicks illegality to which their boss could point.

On 30 March 2007, a plea deal was put into effect. One of the so-called worst of the worst, after five years of governmental filibuster on both sides of the Pacific, was effectively sentenced to nine months detention in an Australian jail.

But even this backdown was just a face-saving charade for the politicians in Australia and the US who had perpetrated a great injustice.

Nearly eight years later, on 18 February 2015, the truth was finally acknowledged. David Hicks’ conviction was set aside by a US court on the basis that he had committed no offence.

It was the final act.

The US courts had acknowledged a year earlier that the offence to which he had pleaded no contest, to escape Guantanamo, was no offence at all..

In the Company of Cowards might just be how Dan Mori felt for most of the time he was acting for David Hicks. There was a 1957 novel, Company of Cowards by Jack Shaeffer, which was the inspiration for the 1964 movie Advance to the Rear about the adventures of a company of misfits during the American Civil War.

But, In the Company of Cowards is also the name of a John Cougar Mellencamp song about generally disreputable behaviour.

It is not often that we get a chance to read an entertaining memoir by a man who did the right thing for no other reason than it was the right thing to do.

May many people read Dan Mori’s In the Company of Cowards and find inspiration along with the entertaining read that it is. May we follow his example in whatever field we are asked to contribute.

And, if we don’t, we just might find ourselves having more experiences, along with any of our politicians, that remind us of the Cougar Mellencamp’s closing chorus:

“ So cover your eyes old man in the moon

Unless you care to see what really is not true

You’re in the company of cowards

It’s hard telling what they will do

You’re in the company of cowards

You’re in the company of me and you”.

Footnote

[1] The author is Michael Dante Mori. He was always known by his family and friends as “Dan”, short for Dante. As he explains, an early Department of Defence release described him as “Michael Mori” causing not a few acquaintances who knew him as Dan to ask whether he was related to that Michael Mori. His publisher obviously thinks there is mileage in the confusion gag, yet.