FEATURE ARTICLE -

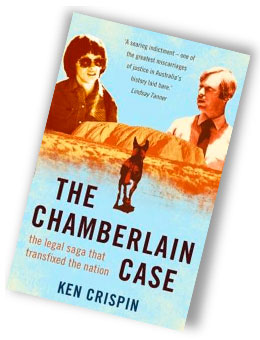

Book Reviews, Issue 61: April 2013

This publication provides an authoritative and detailed account of the circumstances surrounding the 1980 disappearance of three month old Azaria Chamberlain at Uluru (then known as Ayers Rock) and the legal proceedings that followed.

The disappearance of Azaria was the subject of intense interest throughout Australia and overseas. Almost everyone had a view as to how Azaria disappeared. However, a climate of hate also built up against Lindy and Michael, Azaria’s parents, as they were subjected to innuendoes, suspicion and often malicious and unfounded gossip.

The author examines the Crown case at Lindy and Michael Chamberlain’s trial. He also examines the evidence that subsequently emerged and that resulted in their pardon and, ultimately, a finding that Azaria had been taken by a dingo as alleged by Lindy and Michael at the time Azaria disappeared. Of particular importance was the evidence relating to blood, clothing, the behaviour of dingoes, and tracks at the scene of Azaria’s disappearance.

This was a case where there was no body, no eye witnesses, no motive, no weapon, no circumstances of isolation, where opportunities to kill and dispose of a body were obvious, and no confession. Lindy and Michael had, at all times, protested their innocence and their accounts of the relevant events were supported by facts contemporaneously stated by both the Chamberlains and independent witnesses. These accounts, if true, revealed their innocence. Despite this, Lindy was convicted of murder and Michael was convicted of concealing her crime. Lindy spent three years in jail before being released pending a royal commission.

The credible evidence of the likely innocence of the Chamberlains, included:

(a) The Chamberlains were of impeccable character;

(b) Lindy loved the child she was alleged to have murdered;

(c) Lindy had not exhibited any signs of postnatal depression or other psychiatric abnormality;

(d) Aboriginal trackers emphatically stated that Azaria had been taken by a dingo;

(e) There was evidence that a mere two months before Azaria disappeared, a two year old girl had been dragged from the front seat of a car at Uluru while her parents were talking to a nearby ranger, thereby, illustrating that dingoes can be predators intent on removing their prey; and

(f) The chief ranger at Uluru had prophetically commented that a dingo “is well able to take advantage of any laxity on the part of prey species and, of course, children and babies can be considered possible prey”.

The Chamberlains were largely the victim of expert scientific evidence that was presented to them as a fait accompli in circumstances where an independent expert could not effectively review the tests carried out or comment upon the reliability of those results.

The author investigates how, in these circumstances, the Chamberlains were able to be convicted and how it was that the legal system failed them for so long. He argues that there was more at stake than the guilt or innocence of the Chamberlains including scientific controversies, political disputes and whether our much-vaunted legal safeguards are really adequate to protect the innocent.

The Chamberlains endured two inquests, a trial, two unsuccessful appeals (including one to the High Court of Australia) and a royal commission. Three decades passed before there was a finding that a dingo had actually taken Azaria. The author estimates the transcripts of the various proceedings run to 16,000 pages and the exhibits occupy a further 8,000 to 10,000 pages. The Northern Territory Attorney-General has stated that “the amount of evidence, exhibits, transcript and other items … weighed an estimated five tonnes.”

Ken Crispin QC is in a well placed to write on this saga. He had a long and distinguished career in law (commencing practice as a barrister in 1973, Queens Counsel in 1988, Director of Public Prosecutions for the Australian Capital Territory in 1991, a Supreme Court Judge in 1997, President of the ACT Court of Appeal in 2001 and Chair of the ACT Law Reform Commission between 1996 and 2006) and he appeared for the Chamberlains at the Royal Commission. However, despite his links to the Chamberlains, he has dealt with the events in question in a largely objective and dispassionate way.

This publication provides insight into some of the potential flaws of our criminal legal system. The fact that these and other flaws exist in our legal system should lead us to ask how many other people fall victim of our criminal justice system, how many people are presently victim of that system and what can be done to minimise the number of such injustices occurring within that system. We are all at risk.

Despite Lindy and Michael Chamberlain having considerable moral and financial support from the Seventh Day Adventist Church, they were the subject of a great injustice for some three decades before the justice was done. We must ask whether other people without such support would have the necessary resources to have their names cleared in the way that ultimately occurred to Lindy and Michael. It was only the exertion of immense public pressure that resulted in a judicial inquiry and, ultimately, public exoneration.

Without this support, the scientific evidence relied upon by the Crown would probably not have been adequately challenged and the Chamberlains would have remained convicted criminals. Thereafter, any appeal would have been doomed to failure. And there would have been none of the scientific investigation or public pressure that led to the decision to appoint a Royal Commission that ultimately corrected the record and resulted in fair minded people accepting that Lindy and Michael had been innocent people who had not only suffered the tragic loss of a beloved child but had then fallen victim to a grave injustice.

While the years cannot be rolled back and the trauma suffered by the Chamberlain family cannot retrospectively be erased, their case is one that should teach us valuable lessons about the shortcomings in our legal system. This publication is a “must read” for those with an interest in the criminal justice system of our society. It also highlights that we should be most reluctant to wind back long standing protections in our legal system because injustices occur even when such protections exist.

Dan O’Gorman SC

Chambers

18 March 2003