FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 66 Articles, Issue 66: March 2014

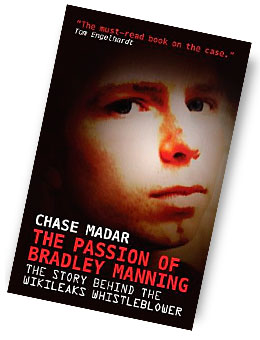

The central points made by Madar in this biography go far beyond an argument that Manning’s disclosure of secret documents was justified and his prosecution and persecution are not. The argument that is developed amounts to a strong critique of establishment even liberal establishment values in the United States. Since so much of what is said and done in Australian politics and public life mimics events in the United States, the points are equally relevant here.

One matter that Madar criticises is a tendency by commentators to explain Manning’s behaviour by reference to his sexuality including his desire to change his gender. The evidence, Madar suggests, is contained in Manning’s own words in the transcription of the online conversations he had with Adrian Lamo, the renowned and convicted hacker, who reported his confessions to the authorities. Manning’s motivations were political and patriotic. He had wanted to serve his country. He was appalled by his country’s actions as they were revealed by the information available to him through his work at the Forward Operating Base Hammer in the Mada ‘in Qada desert east of Baghdad in Iraq. He hoped that, by revealing the information, the public reaction would be such that the worst of the outrages would be brought to an end.

These are motives which are rational and need no pseudo-psychiatric explanation by commentators.

Another focus of Madar’s critique is the hysterical and hypocritical reactions of officials to the WikiLeaks disclosures sourced through Manning. At times, the same elected officials, including Hilary Clinton, Joe Biden and Robert Gates, made contradictory statements about the effects of the leaks. Each of those three made statements that, on the one hand, blamed Manning for wrecking US interests and, on the other, not long afterwards, dismissed the effects of the leaks as negligible.

In the same way, claims that leaks would endanger lives of informants have proved, on investigation by journalists speaking to the informants concerned, to have been baseless. Two examples were an Italian diplomat, Federica Ferrari Bravo and a former Malaysian diplomat, Shazryl Eskay Abdullah, both of whom were bemused that anyone would have found anything they said either memorable or likely to put them at risk.

Another aspect of the hypocrisy criticised by Madar concerns the way in which the rich and powerful leak to journalists, repeatedly, for political gain without anyone showing either concern or the desire to call for their heads on a plate. Madar refers to former White House official, Rahm Emmanuel, whose leaking was so notorious that his colleagues and successors openly joked about it with journalists. Leaking, breaking the laws on which government secrecy is based, is only regarded as a crime if you are seen to challenge the orthodoxy in Washington.

Such double standards call into question the very notion of the rule of law.

Madar also criticises the mainstream US media for failing to report with any focus the effect of the leaked material and the extent to which it contradicts and exposes the dishonesty in the official versions of historical events. Madar mentions aspects of the leaked evidence which exposes the extent to which civilians have been targeted and killed in Afghanistan and Iraq. He mentions the extent to which the positive spin on the war in Afghanistan has been shown to be nothing more than spin. He mentions the official estimate of Iraqi deaths at 109,000, including 66,081 civilians. The existence of this official estimate had, for years, been denied.

Another lurid example is a house raid by US forces in Iraq which involved the executions of one man, four women, two children and four infants. The documents released showed that, while the US had launched an airstrike to destroy the house, local autopsies showed that each of the dead had been shot at close range while handcuffed.

Perhaps of most concern was the evidence of extensive torture by Iraqi authorities of prisoners in their care. This included sexual torture, cutting off of fingers, acid burns and fatal beatings. Although this conduct was well known to US authorities, a secret “Fragmentary Order 242” ordered US servicemen to ignore the conduct of the Iraqi jailors and to continue to pick up prisoners and to hand them over to be tortured.

All this is known. But, for a handful of dedicated journalists and activists, public life goes on in the US without these lurid facts ever being raised as relevant either to the conduct of government or the narrative by which politicians seek to disguise the truths of recent history.

Another aspect of the Manning revelations filled in some of the information gaps concerning conduct of the “legal black hole” at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. The Manning documents spelled out very clearly the extent to which the “worst of the worst” categorisation of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay was so inaccurate as to amount to a lie told, inter alia, to justify the torture and degrading treatment systematically imposed at Guantanamo.

Again, Madar’s critique goes deeper. He draws a connection between Guantanamo, the abuses at Abu Ghraib and the torture of Bradley Manning, himself. Madar sets out in detail the cruel and degrading regime to which Manning was subjected and the way in which, against all available medical advice, he was kept on suicide watch in order to make his life in custody more unbearable. Although such conduct has been condemned by many, Madar points out that many of the criticisms are on the basis that the actions are an exceptional breach of American values.

Rather, the excesses that have come to light are merely the expression of American values as reflected in the day to day operation of every prison operating in the US and accepted without qualm by the majority of the American population.

One observation is that, just like the slaughter at My Lai, no one gets punished. Even when there is a fall guy, he gets to spend some time on house arrest and then walks free.

More fundamentally, the use of torture, generally, and the use of torture to obtain confessional evidence are part of the mainstream prison system in the US. Madar refers to numerous documented examples of such treatment. Solitary confinement, notes Madar, has increased in frequency in recent decades even more than the prison population has grown. In California, for example, prisoners are kept indefinitely in solitary confinement not as a large resort management tool but, for indefinite periods, in every case a prisoner is suspected of being a member of a gang.

And, because the growth in the US prison population is, in many respects, attributable to the racist war on drugs, it is Afro-American and other minority groups who are subject to torture, and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.

Despite criticism by international bodies of the routine and broad scale use of solitary confinement at all levels of the US prison system, the cruel and inhuman treatment inflicted upon domestic prisoners does not give rise to the type of outrage that arose from the exposure of the excesses at Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib.

Madar argues that, until politicians, journalists and media outlets, academics, activists and commentators become serious about preventing torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment at home, abuses will occur whenever the US gets to detain people, including foreigners and others perceived as enemies of the state.

The Passion of Bradley Manning is an important book. The mainstream media, both in the United States and Australia, failed to seriously cover the disclosures that Bradley Manning made possible. The same media failed to debate seriously the inequity of prosecuting Pfc Manning when they, themselves, rely on the leaking of secret information by people in authority on a daily basis.

Perhaps, most regrettably, the mistreatment of Bradley Manning by army prison authorities has hardly been mentioned.

As a polity, we are the victim of the secrecy imposed upon us by our government. To know the truth, as opposed to a narrative that has little contact with reality, we need to appreciate people like Bradley Manning and to stand against their persecution.

The Passion helps us understand why.

Stephen Keim SC

Angourie