FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 102: December 2025, Reviews and the Arts

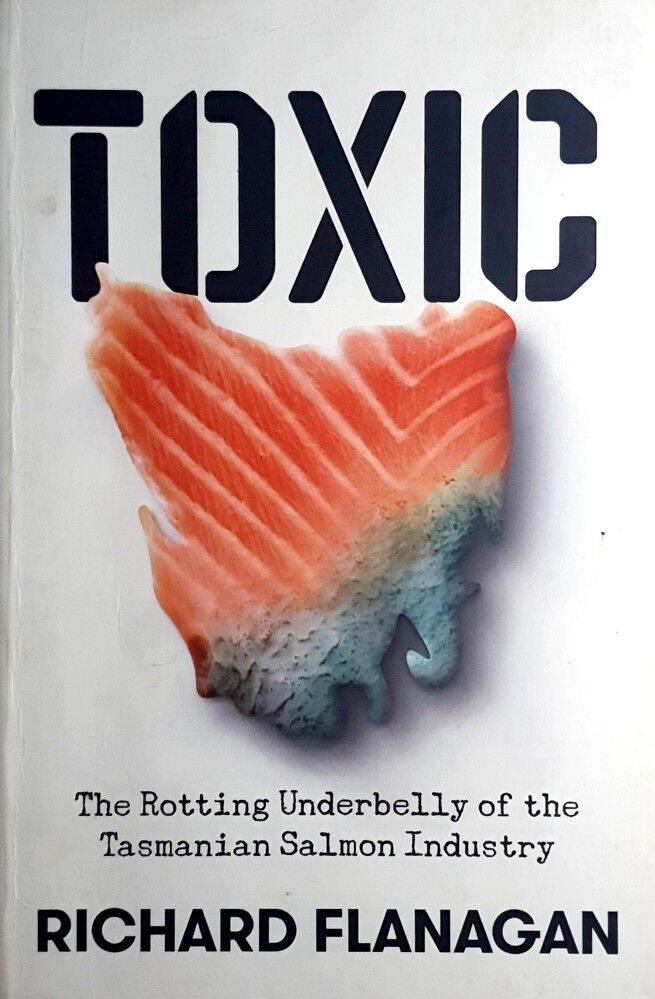

Author: Richard FlanaganPublisher: Penguin Books, imprint of Penguin Random House AustraliaReviewer: Franklin Richards

Toxic is a book with a message, and it delivers that message, unashamedly, like a kick in the guts. The book describes and critiques the Tasmanian salmon industry before exploring the alternatives and imagining how much better things could be without the industry in its current form.

Flanagan draws on the experience of ordinary Tasmanians living near salmon cages and facilities, and others, including scientists and fishers, who have witnessed changes in Tasmanian waters. The changes include muddying of the waters, increased nitrogen load and the loss of animal and plant life. Many of these observers blame the Salmon industry for causing or contributing to the changes.

Toxic begins simply with a beautiful description of the author’s recollection of time before the industry.

‘At the beginning its sea was rich and wondrous. We’d snorkel and fish and swim and beach-comb. Marvelling. So many people came to visit and stayed with us in that old vertical board shack on Bruny Island. And everyone felt it was one of those special, magical places.’

Flanagan goes on to describe how, in 2002 a small fish farm across the water began emitting an annoying noise. He explains how he reported the noise to Tasmania’s responsible government body, the Marine Farming Branch. He relates how the branch investigated the noise and the noise stopped. When the annoying sound returned in 2005, Flanagan, again, complained to the Marine Farming Branch. This time a clearly exasperated official, said he was unable to help and so began Flanagan’s personal struggle. A struggle that continues today. He explains, ‘I found myself falling deeper and deeper into the story of what happened, and how it happened, and all that is being destroyed to make the Tasmanian salmon we eat.’

Flanagan tells us what he has learned and it’s not pretty. He argues that almost everything you know, or think you know, about the industry is wrong. Tasmanian farmed salmon are not free range fish simply growing out naturally in the pristine waters of the Southern Ocean.

Turns out, almost nothing about the industry is natural. Many of the problems stem from the fact that Tasmania’s waters are simply not cold enough for Atlantic Salmon to thrive. So, the industry relies on antibiotics and supplements and physical cleaning processes to keep the fish alive. Without these considerable interventions, the salmon would quickly succumb to disease, infection and pest infestation. Quite simply, they would all die.

Sometimes, even all that effort and expense is not enough to keep the fish alive. Sometimes, climate and ocean conditions conspire so that even the best efforts of the industry fail. One such event early in 2025 was memorable for the world-wide news images of pale fish flesh floating in pens and fat globules washing ashore on Tasmanian beaches.

Flanagan describes similar, earlier events that starkly illustrate the problems for the fish, struggling to survive. But the problem for the industry, and us, the consumers, doesn’t end there. Flanagan writes, ‘If we are what we eat, what our food has eaten in turn matters. Yet it’s easier to find out what you’re feeding your dog than what you’re feeding yourself when you eat Tasmanian salmon.’

Again, the news is bad. Artificially feeding millions of salmon in enclosures carries enormous economic, environmental and social costs. The costs, Flanagan argues, are far reaching. One example is the devastation of Peru’s wild anchovy stocks and the pollution emanating from the country’s fishmeal factories. These problems might be a world away from Tasmania, but they are, nonetheless, problems fuelled by the Salmon industry. When you consider the fact that 1.73 kilograms of mostly food-grade fish go to grow just one kilogram of salmon, it doesn’t seem like such a good deal. Flanagan concludes, ‘Salmon farming is about creating protein by stealing it from others.’

Then there is the chicken feed. Tasmanian salmon are fed in part with chicken meal. Flanagan writes that this is a product which, in 2015, was legally defined as ‘prepared from … the carcasses of slaughtered poultry, such as heads, feet, intestines and frames.’ An unappetising prospect, even for dedicated salmon eaters.

Unsurprisingly, such an unflattering portrait of the Tasmanian salmon industry has had an impact on sales and in the political arena. In Tasmania, it has contributed to the rise and election of several prominent anti-salmon industry campaigners. One recent example is independent, Peter George, recently elected to the Tasmanian lower house.

In concluding his book, Flanagan explains his brutal and forthright contribution to the Tasmanian salmon industry debate. To do this, he returns us to his time on Bruny Island. There he reveals a little of his soul.

He writes of the wrasse and squid and octopus, and the seahorses and sea dragons. ‘It was a world of astonishments, a world of dreams. When I was there ideas and thoughts that were laboured, heavy things, grew fins and wings, became other, alive, strange even to me, and all I could do was follow them into the seaweed to become people, stories, books. They helped me write my stories. I write this in the hope that I might now help them.’