Queensland Law Society Symposium – 2 March 2007

The Honourable Chief Justice delivered the opening address at the Queensland Law Society Symposium which took place on 2 March 2007. To download His Honour’s address, CLICK HERE.

Townsville Introduction of QWCDec Launch – 23 February 2007

His Honour Judge Irwin, Chief Magistrate, delivered the opening address at the QWCDec Launch which was held in Townsville on 23 February 2007. To download a copy of His Honour’s address, CLICK HERE.

Biennial Australian Bar Association Conference – Chicago – 26-29 June 2007

The Biennial Australian Bar Association Conference will be held in Chicago on 26 – 29 June 2007. Major themes to be explored include:

- Regulation and Independence

- Litigation in the US

- The Appointment of Judges: Tenure, Confirmation and Discipline

- The US Constitution and Terrorism

- Scepticism and the Judicial Method

- Charters of Rights and the Role of Courts

For more information contact the Bar Association office.

QUT School of Justice – Research Project

A QUT criminologist is studying former offenders to shed further light on the process of “going straight” with the aim of cutting the growing prison population by helping more people to stop reoffending.

PhD researcher Rob Robertson, from Queensland University of Technology’s School of Justice, is seeking participants for a study that will involve in-depth interviews with men and women who have had no convictions in the past five years after release from one or more years in prison. For more information, please contact Mr Robertson on (07) 3138 7133.

Digital Typing…

No more typing your own work.

Court documents, correspondence, reports or any dictation. Low cost typing. Only $20 per typist hour. Over 10 years’ experience. Confidential, fast, accurate and reliable service. No need to call, just email rawild@hotmail.com. Your work will be typed and emailed back to you.

First Legal Support Solutions

Outsource your digital dictation and enjoy many benefits!

· Experienced legal typist

· Confidential

· Convenient (email)

· Professional

· Affordable

Considering digital dictation? We offer a FREE download of the Quikscribe Recorder. (Conditions apply).

Contact Kristen Edwards (07) 3341 5094, email kae@flss.com.au or visit www.flss.com.au.

Order in Law Transcription

Transcription of all legal documents including court documents, advices, correspondence etc either via digital or tape recording.

- Fast document turnaround

- Flat hourly rate

- 24 hours/7 days

- 5 years’ experience assisting Counsel

- References upon request

- MYOB bookkeeping

Contact: Shannon 0433 194 870, orderinlaw@optusnet.com.au

CPD Points for Contributions to Hearsay

Members are reminded of the following ruling of the CPD Accreditation Committee:

“The CPD Committee will allow 2 CPD points per article published in Hearsay and the Queensland Bar Journal. Additional points may be available on specific request from authors of substantive works.”

CPD Calendar 2006/2007

To download the CPD Calendar 2006/2007.

To place an advertisement in Hearsay

Contact Emma Macfarlane on (07)3236 4020 email hearsay@www.hearsay.org.au

The translation in format, from PDF to Web-page, should render Hearsay even more attractive to the reader or browser.

I commend the Bar Council for its support for this initiative, and Martin Burns and his team for their valuable contribution.

The liveliness of the issues confronting the contemporary barrister more than warrants a publication on this regular and comprehensive basis; and it has the added attraction of being interesting and even, not infrequently, entertaining.

The Hon Paul de Jersey AC

Chief Justice of Queensland

The Kokoda endeavour entails (depending upon one’s level of fitness) about eight weeks of training, a charter flight to PNG, a day in Port Moresby (probably the most dangerous part of the trip), 8 days on the track (without alcohol) and a day or so afterwards counting your blessings you are still in one piece.

Guy Waterman and I joined a group of about 25 mainly ex Queensland University rugby players on the 2005 Anzac Day trek. We followed in the footsteps of previous Queensland Bar trekkers Jennifer Rosengren and Dominic Murphy. Brian Cronin followed in 2006. They were afflicted by bad weather. Our trek was slippery but the conditions were mainly dry.

Our middle aged group (average age 50) trekked for 8 days. Each carried a 15 kilogram back pack (containing personal gear, 1.5 days rations and 5 litres of water) with no spare clothing (one set for trekking by day and another for sleeping by night after a rinse in the nearest stream).

Our middle aged group (average age 50) trekked for 8 days. Each carried a 15 kilogram back pack (containing personal gear, 1.5 days rations and 5 litres of water) with no spare clothing (one set for trekking by day and another for sleeping by night after a rinse in the nearest stream).

The following is a summary of the pleasure and pain that was our trip.

Day 1

Charter flight from Brisbane to Port Moresby. Excited. New trek boots worn on plane because my 2003 pair fell apart late in training. Sat in the plane on the tarmac in Moresby for 3 hours due to a dispute about “paperwork”. Dispute coincidentally falls hard on the heels of an incident in the previous week in Australia when a piqued PNG Prime Minister was required to remove his shoes so as to pass through an airport metal detector. Bus trip by night from airport to Crowne Plaza Hotel. Scary. Fires at side of road in suburbs. Throngs of milling locals. Walked 50 metres beyond guarded and razor-wired central city hotel high fences before, acting prudently, returning. Many beers on cusp of adventure.

Day 2

Day 2

Trucked to Owers’ Corner for the start of the south-north trek. Due to bad road conditions, trucks drop us off 5 kilometres short of the “gates” to the trail. Meet up with porters (carrying tents, medical kits, pots, additional rations). They are proud men, small in statute, with immense strength and very pleasant in disposition. Our trek leader Al Forsyth is an ex SAS sergeant major. We were trained to, and did, obey his every word. That is our guarantee of safety. Wade chest deep 50 metres across Goldie River. Trek up and down mountain spines. Do not step sideways or you will slide 20 metres only to be stopped by a tree. Camp, with too many other trekkers, at abandoned Uberi Village. Sleep soundly in one man tent (carried and erected by porters) in sleeping bag and on sleeping mat (carried by trekker).

Day 3

Day 3

First of seven days putting back on previous day’s wet and smelly trek vest, tights, shirt, socks and trek boots. Climb the “Golden Stairs” to Imita Ridge. This was the furtherest south Australian forces retreated between date of Japanese invasion at Buna on 21 July 1942 until following 17 September. Australian soldiers told to “fight or die here”. Australians then advanced from 27 September until Japanese were defeated on 4 January 1943. Very tired at this point but fortunately, unlike those in 1942, no-one was shooting at me. Camp on a high cutting at Ofi Creek. As usual by night, put our ration pack food in one pot and share it out. One-quarter of our number now sick with stomach pains, chest ailments and exhaustion. Buddy system helps. Bad snorers (I feel for their spouses).

Day 4

Day 4

Drizzling conditions of previous days give way to sunshine (which continued). Barricades across the track erected by villagers who complain of little or no money paid to them by PNG Kokoda Trail authority. Fortunately trek company (Executive Excellence) has good relationship with village head men. Villagers very friendly. Often offered us fruit and vegetables from their steep gardens. Lunch at Vaurebi Guest House (an elevated open slab hut, with no furniture, and fitted with a loose thatched roof). Cross the Brown River. Climb the Maguli Range (1,357 metres). As usual very little flat country in between. Constantly climbing or descending – the latter more dangerous. Constantly falling over. Camp at Menari Village. Play touch football with Mal Meninga (who was also trekking) and villagers. Must remember each day to take anti-malarial medication (the cry each morning is “Doxy-up”).

Day 5

Climb Brigade Hill. Many Australian soldiers died here. Fortunate to have multiple trekker and amateur historian, Bill James, to inform us each day of the Trail’s history. Marvel at soldiers’ exploits and endurance. One or two villages each day. No roads anywhere on track. Occasional steep airstrip. Come across several trekkers who are slumped at edge of track and can go no further. Only way out is to be assisted by friendly villager or arranged porter. Possibly helicopter pick up in a few weeks. Leave them extra food. Camp at Efogi 2 Village. We hear NRL games being called in pidgin on crackling radio in a village hut. Japanese memorial at village. No graffiti. Local vegetables and fruit a blessing after ration packs. Must eat or cannot climb and will fall ill.

Day 6

Day 6

Climb to Naduri. Hot. Anti-malarial medication sensitises skin. Last “fuzzy wuzzy angel” lives there. Ten kina for a photograph with him. Much militaria (eg, hand grenades, bayonets, helmets) recovered from track on rough display. Pass Kagi Village where airstrip resembles a long slippery slide. I turn away when a plane lands on strip, expecting a casualty. Constant hydration is essential (the cry all day is “water up”). Camp at “tin shed” clearing in forest. Members of trek group start opening up about their lives. Oldest member of our group (former senator David MacGibbon — aged 71) gets a second wind and puts we younger guys to shame.

Day 7

Walk through the Kokoda Gap. Former wartime air route. Orthopaedic surgeon John Fraser’s father used to fly through it supplying Buna and Gona in the north towards end of Kokoda campaign and used to look down to the mountains and shake his head. Shook his head again at John wanting to walk it, not fly it. Climbed Mt Bellamy. Cross fast flowing and deep Eora Creek several times on the various Templeton’s crossings. Makeshift bridges made of narrow trunks. Half of our group now quite ill. To keep them afoot John Fraser, paediatrician Ron James and vet Tim Foote mix medicines. Great swimming/bathing and camping conditions that night at Eora Creek. Surreal.

Day 8

Steep descent down balance of Eora Creek. Slight drizzle. Mountain village gardens magnificent. Most of village children and also their dogs have names of NRL players (eg, “Alfie Langer”). Mal Meninga considered deity by these people. Trekked into Isurava Memorial on eve of Anzac Day. A piper playing. The hairs on my neck are electric. Kingsbury VC killed here in 1942 protecting his mates in retreat. We stand silent where he was cut down by a Japanese sniper. We camp around the memorial. Maintained by Australian War Graves Commission. Four polished granite slabs facing one another marked, respectively, “Courage”, “Endurance”, “Mateship”, “Sacrifice”. Never have I felt this way before. Proud to be Australian.

Day 9

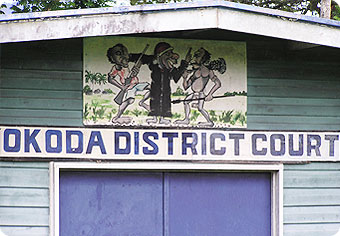

Up at 4.00 am. Dawn service. Our ex SAS warrant officer leader Al reads the prayer. I am so in awe of this man now I would jump off a cliff if he told me it was the right thing to do. Local choir of villagers sing PNG and Australian anthems in pidgin. Dawn provides the view of a lifetime down through the mountains to the cloud shrouded lowlands of Kokoda. I am in thrall of the beauty of this country. Steep descent down to beautiful village of Hoy where I lie fully clothed in a stream to cool down. Please let me sleep. Long flat trek then to Kokoda township. I see a shop and buy a can of coke. It is hot. There is overhead electricity infrastructure here (not in mountain villages) but it has not worked for 4 years. Visit the local catholic church which is beautifully maintained. Camp on Kokoda township oval. Local police (armed with automatic weapons), for a fee, procure us slabs of hot beer from nearby township. Went down surprisingly well after 8 days’ abstinence. Local villagers (one was a copper who earlier “slabbed” us), bedecked with birds of paradise feathers, put on a show to remember. Visit local court house which has unique sign.

Day 10

Flown by light plane (15 seater) from lawn strip outside Kokoda back to Port Moresby and the Crowne Plaza. Beers and tears. Dr Ron James receives our “Kingsbury” award for keeping our many sick troops on their feet: “I usually treat babies”, he says. So what’s different! Visit Bowana War Cemetery outside Moresby. Maintained by Australian War Graves Commission. 5,000 Australians buried here. Speechless. Told vehicle car-jacked outside gates on Anzac Day as Australian High Commissioner leaving following ceremony.

Day 11

Charter flight from Port Moresby to Brisbane. Many go to the Brekkie Creek for a steak. I just want to go home. Had intended to go into chambers the next day. I let it go four days.

Being in dry clean clothes feels strange. After a day or two, I long for my smelly shirt and tights, together with the afternoon rinse in a crystal clear stream. I “Doxy-up” for 14 days post-trek and, just as well, as one of my fellow trekkers subsequently fell ill with malaria.

Richard Douglas SC

Discuss this article on the Hearsay Forum

The taking of oaths and the making of affirmations by witnesses in the courtroom are solemn occasions. The avowal of a witness that he or she will tell “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth” is central to the integrity of the evidentiary process. The vow is so serious that a person who breaches it is subject to penal sanction for perjury.

The short ceremony during which the oath or affirmation is administered has traditionally been accorded great respect by all those present in the courtroom. The tradition in Queensland, as in other states and in England, is that strict silence should be observed while this step is carried through. That means that there should be no conversing or shuffling of papers at the bar table while oaths and affirmations are being administered.

The short ceremony during which the oath or affirmation is administered has traditionally been accorded great respect by all those present in the courtroom. The tradition in Queensland, as in other states and in England, is that strict silence should be observed while this step is carried through. That means that there should be no conversing or shuffling of papers at the bar table while oaths and affirmations are being administered.

Members are reminded of the importance of this tradition. It is a mark of our respect for an event which is not mere ritual, but is of great significance to the court and the witnesses.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, declare that, in the determination of civil rights and obligations, and criminal responsibility, all people are entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law. Competence, independence and impartiality are the basic qualities required of judges as individuals, and of courts as institutions. Fair and public hearings are the required standard of judicial process. Confidence in the courts is a state of reasonable assurance that these qualities and standards are met.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, declare that, in the determination of civil rights and obligations, and criminal responsibility, all people are entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law. Competence, independence and impartiality are the basic qualities required of judges as individuals, and of courts as institutions. Fair and public hearings are the required standard of judicial process. Confidence in the courts is a state of reasonable assurance that these qualities and standards are met.

The values identified in the international instruments to which I have referred are generally accepted, but their practical content is not entirely self-evident. The matter of competence, for example, covers not only possession of formal legal qualifications and knowledge of the law, but also an ability to conduct a hearing, to apply the rules of procedure and evidence, to control counsel and witness, to evaluate evidence and arguments, to make a sound decision, and to give adequate reasons for that decision. Nowadays, it also covers demeanour, sensitivity towards parties, witnesses and even lawyers, awareness of human rights issues, diligence, and efficiency. The topics of independence and impartiality, which are related to each other, also are complex, and may be the subject of sophisticated analysis. It is a good thing that modern judges are concerned with public perception, but they should not allow that concern to foster an illusion of a public constantly ruminating about such matters as judicial training and development, administrative arrangements between courts and the executive government, or rules of disqualification for bias. These subjects are important, but outside certain professional or specialist groups they are not matters of wide interest.

All institutions of government exist to serve the community, and the judicial branch of government, which has no independent force to back up its authority, depends upon public acceptance of its role. That acceptance requires a certain level of faith. What is it that sustains, or threatens, such faith? That is not an easy question to answer. There are some obvious topics of importance, such as a judiciary’s reputation for honesty. There are places where judicial corruption is a serious problem. Happily, this has never been an issue in Australia. Other considerations that might affect the public’s view of the courts are less easy to identify.

All institutions of government exist to serve the community, and the judicial branch of government, which has no independent force to back up its authority, depends upon public acceptance of its role. That acceptance requires a certain level of faith. What is it that sustains, or threatens, such faith? That is not an easy question to answer. There are some obvious topics of importance, such as a judiciary’s reputation for honesty. There are places where judicial corruption is a serious problem. Happily, this has never been an issue in Australia. Other considerations that might affect the public’s view of the courts are less easy to identify.

There is a problem about treating people outside the court system as a class with a consistent set of opinions about courts. Such people include some, such as lawyers, who participate regularly in the work of the courts and have a clear appreciation of the strengths and weaknesses of the system; others who are directly affected by the judicial process, such as litigants, and whose success or failure may colour their views; others, such as witnesses and jurors, whose encounters with courts are brief, but who may take away strong impressions; others whose occupations give them a special interest in or knowledge of aspects of the judicial process, such as politicians, public officials, police officers, medical practitioners or social workers; others, such as reporters and commentators, who observe, describe and appraise the working of civil or criminal justice, and teachers and students of law. They include many who merely take the same kind of occasional notice of, and interest in, courts as they do of any other public institution. Perhaps the largest group of all are people who think about courts only on the rare occasions when something briefly attracts their attention. Many of those are people whose state of opinion about the justice system may run no deeper than a reaction of approval or disapproval to some recent decision that has come to their notice.

We talk about public confidence in such things as the courts, the democratic process, the institutions of government, or other aspects of public life as though we are referring to an observable state of mind of a sufficiently large group to represent public opinion. We assume that such confidence is as measurable as, say, the approval of a political leader, or the popularity of a celebrity. Many of the topics for discussion at this Conference assume that we are concerned with an actual, observable state of mind; and much of what I have to say will accept that assumption. I wonder however, whether, in some judicial discussion, public confidence is really a theoretical construct; something to which we appeal in order to objectify our reasoning, rather as we appeal to the hypothetical fair-minded lay observer when we apply the principles of law about apprehended judicial bias. When judges are doing that, they ought to say so. In certain contexts it is legitimate, but unless it is acknowledged, there is a danger of misunderstanding. It is also worth keeping in mind that one of the problems that courts have with the fair-minded lay observer is knowing how much knowledge or understanding of the judicial process is to be attributed to that disembodied symbol of rationality and wisdom. There may be a difference between what members of the public actually think about the courts, when they think about them at all, and what a judge believes would or should cause a hypothetical, fair-minded, well-informed observer to be concerned about judicial competence, independence or impartiality. Judges are insiders to the process. Some things that might concern them may be matters of indifference to most people outside the system; and some things that may concern people outside the system may be dismissed as insignificant by judges. Any professional group that seeks to assess the esteem in which it is held by outsiders is undertaking a risky exercise. They need to be sure they are listening to voices from outside, and that they are not working in an echo chamber.

Much of what we call public confidence consists of taking things for granted. Consider, for example, public confidence in the electoral process. Australians generally appear to assume the integrity of the electoral system without knowing much about how it works. Outside the political class, professional commentators and a few amateur enthusiasts, how many people understand how electoral boundaries are fixed, or follow the work of the Electoral Commissioner, or know of the existence of Courts of Disputed Returns? Yet these arrangements are essential to democracy. Occasionally, as with the case of Bush v Gore in the United States, outcomes of enormous consequence may turn upon them. Most Australians probably know that there are countries where the electoral process is flawed; where elections routinely are accompanied by intimidation and corruption; and where disputed outcomes are more likely to be decided by the armed forces than by the judiciary. Yet, unless our attention is caught by some widely publicised issue, we are content to accept that our elections are basically clean, and that the results, whether we like them or not, reflect the will of the people. For most citizens, public confidence in the electoral process is based more upon undisturbed assumptions than upon reasoned opinion. Where do those assumptions come from? What kinds of event would shake them? What could be done to reinforce them? There are cultural factors operating here, not necessarily based upon any particular virtue of our people, but rooted in history.

Much of what we call public confidence consists of taking things for granted. Consider, for example, public confidence in the electoral process. Australians generally appear to assume the integrity of the electoral system without knowing much about how it works. Outside the political class, professional commentators and a few amateur enthusiasts, how many people understand how electoral boundaries are fixed, or follow the work of the Electoral Commissioner, or know of the existence of Courts of Disputed Returns? Yet these arrangements are essential to democracy. Occasionally, as with the case of Bush v Gore in the United States, outcomes of enormous consequence may turn upon them. Most Australians probably know that there are countries where the electoral process is flawed; where elections routinely are accompanied by intimidation and corruption; and where disputed outcomes are more likely to be decided by the armed forces than by the judiciary. Yet, unless our attention is caught by some widely publicised issue, we are content to accept that our elections are basically clean, and that the results, whether we like them or not, reflect the will of the people. For most citizens, public confidence in the electoral process is based more upon undisturbed assumptions than upon reasoned opinion. Where do those assumptions come from? What kinds of event would shake them? What could be done to reinforce them? There are cultural factors operating here, not necessarily based upon any particular virtue of our people, but rooted in history.

Courts are more often in the news than the electoral system. They exist to resolve conflict, and whenever there is conflict there will be people who are ready to identify and complain about faults in the conflict resolution system. Yet courts also have the benefit of cultural reinforcement of their authority, and of faith in their integrity. This is a society which accepts the rule of law as the natural order of things. The decisions of courts are obeyed, even when they are unpopular, or offend powerful interests. Governments engage in civil litigation, sometimes against one another. Criminal cases are conducted as contests between a government and a citizen. Governments routinely accept and obey court decisions. Courts make decisions adverse to governments, sometimes in matters of great political importance. They may antagonise large sections of the community. Yet it would be beyond the contemplation of most citizens that those decisions might be not obeyed.

There may be no scientific method of measuring a society’s commitment to the rule of law, or predicting what kind or degree of dissatisfaction would destabilise that commitment. Even so, analysis of what needs to be done to give citizens engaged in civil disputes, or in the criminal process, a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal enables us to identify some issues that go to the essence of the matter. A number of those issues will be addressed during this Conference. I will mention only a couple that are of special interest to me.

Public participation in the administration of justice is a part of our legal tradition. Trial by jury remains the procedure by which most serious criminal cases are decided, although in recent years, in the interest of reducing cost and delay, there has been a trend towards making more offences triable summarily. It is important for Parliaments to keep in mind the public interest in involving the community in the administration of justice, especially criminal justice. Through the jury system members of the public become part of the court itself. This ought to enhance the acceptability of decisions, and contribute to a culture in which the administration of justice is not left to a professional cadre but is understood as a shared community responsibility.

When I entered the legal profession 45 years ago, juries played an extensive part in the administration of civil justice. In most State jurisdictions, that has changed. In some States, civil juries are rarely used. Federal courts, which are of relatively recent origin, have never made significant use of juries. There are now many advocates who have never participated in a jury trial, and there are judges who have never presided at such a trial. Whatever we may think of this reduction in the role of civil juries, we ought to be aware that it involves a cost. If the traditional participation of juries in the common law civil process is to be reduced permanently, as seems inevitable, then we should be conscious of the fact that we are cutting ourselves off from the community in one way, and we need to establish other lines of contact. For example, Australian courts now have Public Information Officers; something that was unheard of 45 years ago. They are not there just to deal with crisis management. They have an educational function that should be used in a conscious effort to replace the information function that once was served by the use of civil juries. Again, before Parliaments are tempted further to reduce the importance of civil juries they ought to reflect on the way they serve to promote public awareness of the court system. Reduced public participation, through trial by jury, in the administration of civil justice has increased the separation between courts and the community, and we need to find ways to compensate.

One aspect of competence is the capacity of the system to identify and correct error. All human systems are fallible, and any justice system can miscarry. The ability of the courts, through the appeal process, to correct error is important to the acceptability of the process. This is an area in which the diminishing role of the jury has mixed effects. Jury verdicts are given without reasons. The acceptability of the outcome is based on trust in the combined wisdom of a group of citizens, chosen at random, directed by a judge as to their legal obligations, and applying common sense and community standards to the resolution of issues of fact. It is hard to appeal against a jury verdict. The system has the advantage of finality, and the related disadvantage of inscrutability. In the case of a trial by judge alone, the judge must give reasons. The acceptability of the decision is based on the cogency of the reasons of a professional decision-maker. It is easier to appeal against a reasoned decision. It is easier to identify error. Miscarriages of justice have the capacity to shake confidence in the system, but the capacity of the system to correct itself might be expected to reinforce confidence. It may be that the spirit of our times attaches less importance to finality and more importance to the need to know, and to be able to challenge, reasons. It would be interesting to know what the public think of the comparative merits of trial by jury and trial by judge alone. I wonder what percentage of people have a view on that question. Perhaps we judges overestimate the importance that people attach to our reasons. How many outside the legal profession have ever read reasons for judgment? The fact that juries do not give reasons for their decisions, and that judges give what would be regarded by many people as elaborate, sometimes over-elaborate, reasons is often completely overlooked in commentary about the role of juries. Does that suggest that something we regard as fundamental in the judicial process is something that people outside the process regard as insignificant? That is a sobering thought.

Another aspect of competence is the professionalism of judges and the related question of their appointment. Some interested citizens have opinions on these topics, but I am not aware of any reliable studies of general opinion about them. This also may be an area in which people are tempted to identify their own opinions with public opinion, or to concern themselves more with what public opinion ought to be than with what it is. I have some views about what is needed for a competent judiciary. I believe that most of those views would be shared by most other judges. Yet, from time to time, different views are expressed by other people. Some of those people may be wiser than I am, although on this topic I can probably claim to be comparatively well-informed. How would I know how widely my opinions are shared in the general community? We all want courts to enjoy public confidence; so we ask ourselves what would affect our personal state of confidence. That is a reasonable approach, as far as it goes, but it does not go very far.

An assurance that courts decide cases free from external influence in the form of pressure from governments or other powerful interests or favouritism of some litigants is basic. The ultimate test of such assurance is whether people believe that, in a legal contest between a citizen and a government the judge will hold the scale of justice evenly. It is also important that people believe that judges are committed to deciding cases of all kinds, regardless of the identity of the parties, fairly and according to law. There are some who say that impartiality is a myth; that, whether they realise it or not, judges are controlled by personal impulses and inclinations, perhaps formed unconsciously; and that the best judges are those who break free of the myth of impartiality and exercise judicial power in order to promote social ends. If this were ever to become a general opinion of the way judges behave, then there could be no public confidence. Manipulating the law in pursuit of a judge’s personal agenda might seem clever to an enthusiast for a cause, but it would be destructive of the authority of courts and therefore, ultimately self-defeating. If the idea of judicial impartiality is consigned to the intellectual scrap heap, judicial authority will soon follow it.

There is a useful practical indicator of the judiciary’s general reputation for impartiality. The readiness with which politicians, the media, and interest groups demand a judicial enquiry as the procedure for investigating controversial and sensitive issues surely reflects the fact that judicial process enjoys a certain reputation for integrity. The demands are rarely made because a judge, or former judge, has some special professional expertise that sets him or her apart from all others. Rather, the assumption is that the outcome of an enquiry will be accepted more readily by the public if it can be described as judicial. It is obvious that one of the attractions to government of former judges to conduct enquiries is the aura of impartiality that is brought by their former status. We ought to find this encouraging.

Australians largely take for granted the political independence of judges. Some judges have well-known political backgrounds. Once appointed, however, they are expected to avoid political activity. If a judge were to indicate a preference for one side or the other of a political issue, that would attract applause from some partisans on the side favoured by the judge. But thoughtful people would recognise the inappropriateness of such conduct, and even those on the side of politics preferred by the judge would feel uneasy. Abuse of public office by engaging in inappropriate political activism is easily recognised, especially by politicians, who are quick to notice when a political point is being made, and quick to complain when it is being made by someone who should keep out of politics, even if it happens to be a point in their favour. Politicians understand that if latitude is extended to their friends today, then tomorrow it will be the turn of their opponents. Politicians both reflect and influence the way the community views public institutions and office-holders, including courts and judges. They are keen observers of conduct that reflects on judicial independence and impartiality. They are too shrewd to approve a particular instance of such conduct just because it happens to support their side of politics.

Nevertheless, the people whose opinions are most influential in affecting the way the public see the courts are lawyers, especially those whose work regularly takes them into the courts. As a class, they are knowledgeable and critical observers of judicial behaviour. And, as a class, they have plenty to say, both to one another and to the public, about judicial performance. They are not notably charitable; and not notably reticent. The standards of competence, independence and impartiality that they apply in their observation of the work of the courts are, in most cases, demanding. It is essential that the courts enjoy their confidence. Without the confidence of the legal profession, it would be impossible for courts to enjoy the confidence of the public. Their good opinion of the courts is not sufficient; but it is necessary. A litigant’s perception of the judicial process is likely to be strongly influenced by the lawyer’s perception. Lawyers tell litigants what to expect. They predict outcomes. They express opinions about decisions, and prospects of appeal. The lawyer’s perception of the judge, or the court system, or the legal process will be communicated to the client and, through the client, to the public. The judicial branch of government should keep itself well-informed about what the legal profession thinks of its performance; not because it can expect comfort from professional solidarity, but because the views of lawyers influence their clients, and many members of the wider public.

How do courts know what people think of them? Some classes, such as politicians, or lawyers, or media commentators, are communicative. What of the silent majority? Surveys of public opinion are sometimes undertaken on particular questions, such as sentencing. (I am referring to serious surveys; not to the kind of polling done for entertainment.) These can provide useful insights. Occasional clamour over controversial decisions, such as unpopular sentencing decisions, may create concern, but it needs to be kept in perspective. We are often told that modern Australians are sceptical of all authority. I do not doubt that. But they are also sceptical of information, and commentary. The fact that people allow a tide of information and commentary to wash over them does not mean that they form serious opinions without making any attempt to evaluate what they read or hear. Their opinions about the reliability of information and commentary are themselves the subject of surveys, and those surveys do not indicate uncritical faith.

The nature of news affects what is published about courts. The things that sustain confidence in an institution are not likely to be newsworthy. Things that shake confidence are more likely to be newsworthy. Inevitably, therefore, the public hear more about the latter than the former. But people understand that. There is nothing new about this. All people in public life, and all institutions, have to cope with it. Bad behaviour attracts attention. Commitment to the service of the public does not. Consumers of information have an appetite for bad news; naturally, commercial providers of information bear that in mind. If a bridge collapses, that is news. Why would anyone publish a story about a bridge that remains standing? If a victim of crime says that a sentence is outrageously lenient, that is newsworthy. If a victim says that a sentence is fair and reasonable, that is not newsworthy. Naturally, the public will hear more from people who criticise the system than from people who think it is working well. To complain about that is like complaining about the weather.

There is another side of this topic that should be mentioned. We are devoting two days to the question of public confidence in the judiciary. It might be worth giving a thought to the matter of judicial confidence in the public. Some of the alarm that is expressed about the effect of bad news stories, vindictive commentary, and ill-informed or malicious criticism, gives the public little credit for discernment. Judges ought to have enough confidence in the public to accept that the best way to sustain confidence in the courts is to do a good job. They should not be indifferent to public opinion; on the contrary, it should be a matter in which they take an informed interest. At the same time, there is every reason to believe that people generally value the courts. If it were otherwise, how could their commitment to the rule of law be explained? There are, of course, degrees of confidence, but without a substantial level of assurance of the competence and integrity of the courts people could not transact business, arrange their personal affairs, and order their lives with reasonable security. I said earlier that confidence in any public institution most often takes the form of assumptions that people make. Law-abiding citizens, whether they are conscious of it or not, assume, in many different ways, the competence and integrity of the judicial branch of government. Those assumptions run deep. They are a form of cultural inheritance from our predecessors. They provide a reason, not for complacency, but for optimism. And they remind us that we are only temporary custodians of the collective reputation of the judiciary, and that we ought to take care to pass it on intact.

It is important not to confuse confidence with popularity. It is not the business of judges to try to please when they make their decisions. Doing justice without fear or favour requires, from time to time, making decisions that will displease some, perhaps many people. The public understands that. Confidence in the courts includes trusting them to pursue justice, not applause.

The Hon. Chief Justice Murray Gleeson, AC

Discuss on the Hearsay Forum

Junior Bar Report

Welcome to the very first Junior Bar Report. The target readership for this column are barristers of not more than five years’ standing. Rather than use descriptors such as ‘junior, junior’, ‘baby juniors’ or ‘five-year barristers’, I will hereafter simply refer to such counsel as junior barristers … and hope that everyone remembers who I’m talking about.

By my rough calculation, junior barristers currently make up about 25% of the total membership of the Bar Association of Queensland. I currently serve on the Council of the Bar to represent the interests of junior barristers and, as such, this column (and the associated Forum) represents a real opportunity for junior barristers to express their timely and considered views on the issues that affect them. Do junior barristers receive adequate training? Does the pupillage system work or should it be changed? How does a junior barrister stay in work? How should a junior barrister deal with practical problems such as finding chambers or managing an overdraft?

By my rough calculation, junior barristers currently make up about 25% of the total membership of the Bar Association of Queensland. I currently serve on the Council of the Bar to represent the interests of junior barristers and, as such, this column (and the associated Forum) represents a real opportunity for junior barristers to express their timely and considered views on the issues that affect them. Do junior barristers receive adequate training? Does the pupillage system work or should it be changed? How does a junior barrister stay in work? How should a junior barrister deal with practical problems such as finding chambers or managing an overdraft?

It is my intention for this column to address topics such as these and, in the process, hopefully spark some discussion on the Forum. I welcome any comments on the Forum regarding this, and future columns. Indeed, I encourage junior barristers to make use of that facility.

It won’t all be serious stuff though. I am happy to receive and relay any and all anecdotes, photographs, rumours and news from the social scene. On that note, I went along to drinks in the Bar Common Room on Friday, 23 February 2007 for barristers of not more than 3 years’ standing. It was a very well attended event, with many Bar Council members and Silk present to hand out some advice over a few beers. Personally, I thought it was a great way to welcome those who had just completed the Bar Practice Course and to meet our peers. I hope that it remains a fixture on the calendar in the future. I should also say that the drinks proved a fertile hunting ground for Bar cricket recruitment, with the President giving the team an admirable plug. It was only a matter of time before persistence and alcohol claimed some victims and I commend Tony Moynihan SC and David Meredith for not recanting the following Monday morning despite their lack of whites or, in their words, “talent”. Despite their misgivings, I am sure they will give the New South Welshmen something to talk about…

Chris Crawford

The South-Western Downs Bar

The South-Western Downs Bar

This is the first time that someone has asked for a report from the South-West Downs Region, and I am grateful for the opportunity.

There are five members of the bar association that have chambers in the Downs Region. One of our members, namely Phillip Crook, practises out of Warwick. Robbie Davies, Julie Michael, Scott Lynch and myself all have chambers in Toowoomba.

The region is well served by the Judiciary. In a normal calendar year the Supreme Court goes on Circuit and visits Toowoomba (4 weeks) and Roma (1 week). The District Court visits various centres namely, Toowoomba (22 weeks), Warwick (6 weeks), Stanthorpe (2 weeks), Roma (8 weeks), Dalby (3 weeks), Charleville/Cunnamulla (6 weeks), Kingaroy (10 weeks) and Goondiwindi (4 weeks).

There are two permanent Magistrates in Toowoomba and one permanent Magistrate in Warwick, Dalby, Charleville and Kingaroy, each of whom visits the various towns in their local jurisdiction.

We are all looking forward to the first edition of Hearsay to be launched at the BAQ Conference to be held at the Gold Coast on 17 and 18 March 2007.

A number of us will be venturing down the mountain to meet a number of you at the Gold Coast. We look forward to seeing you there.

If any counsel is visiting Toowoomba, I would like to extend an open invitation to join me in a little drink and chat. I can be contacted on 0408 871135 and we can indulge “in vino veritas”.

Frank Martin

The Gold Coast Bar

Although relatively small in number, the Gold Coast Bar Association is a proud association boasting many senior members of the Queensland Bar.

Late last year at a swearing in ceremony for Magistrate Graham Lee, I heard a senior local member of the Bar explain how the Gold Coast Bar has evolved in recent years. It was said that, “In years gone by, the Gold Coast Bar was thought of by others as a shallow sandy stretch of water at the southern tip of South Stradbroke Island, dangerous to negotiate, with murky waters and to be avoided at all cost” .

However, I am pleased to say that the Gold Coast Bar is far removed from that description and in reality is a Bar which has a wealth of experience with a large number of experienced practising Barristers and at least two large chamber groups.

The local Bar has always been home to a well respected local District Court Bench and Magistracy in the past. The local District Court bench has recently undergone a change with two of the three local Judges (Rackemann DCJ and Dearden DCJ) departing for Brisbane and Beenleigh respectively. The Association thanks the Judges for their contribution to the local profession and wishes them all the best in their new districts.

His Honour Judge Newton has remained as the long standing resident Judge, and it was with great pleasure that the Gold Coast Bar Association held a welcoming lunch for His Honour Judge Wall QC on 23 February 2007.

His Honour Judge Newton has remained as the long standing resident Judge, and it was with great pleasure that the Gold Coast Bar Association held a welcoming lunch for His Honour Judge Wall QC on 23 February 2007.

His Honour was welcomed as the newest resident District Court Judge. His Honour Judge Newton was an Honoured guest of the association as well.

Judge Wall QC was welcomed by way of a gathering of the association executive of Bernie Reily (President), Dane Thornburgh (Secretary), Mark Whitbread (Treasurer) and other members of the Association.

His Honour was welcomed in true Gold Coast style at the Southport Yacht Club. The afternoon was spent with members mixing with their Honours while enjoying the splendid view over the vast fleet of vessels which call the Yacht Club home, as well as sampling some of the Coast’s best seafood, and some fine wines.

Bernie Reily delivered a welcoming speech to His Honour and Judge Wall QC kindly exercised his right of reply, which set the tone for the afternoon.

His Honour read from a transcript of one of his first matters here on the Gold Coast in which the accused was quick to discuss what he saw as the Judges professionalism, and was extremely impressed with the way His Honour ran his Court. the following is an excerpt:

HIS HONOUR ——- And you are discharged………

ACCUSED——– Thank you, your Honour. And thank you for being a fair and unbiased judge in the matter, thank you very much.

HIS HONOUR——– That’s what I’m here for.

ACCUSED———- Yeah, well, it’s very rare that you get it these days, Sir, refreshing to see.

HIS HONOUR—— Thank you.

ACCUSED——– And your sense of humour, your Honour.

While the afternoon was a chance for senior members of the Bar such as Matt Pope to discuss previous experiences he had shared with Judge Wall QC at the Townsville Bar, the afternoon was also a great opportunity for the local Bar to renew acquaintances and introduce themselves to His Honour, as well as spend some social time with Judge Newton.

Judge Wall QC comes to the Southport bench with a wealth of experience and the Bar looks forward to appearing before His Honour.

Her Honour Judge Kingham has also been transferred to Southport, however Her Honour was unfortunately unable to attend the welcoming lunch. Although disappointed that Her Honour was unable to attend, it does provide an excuse to hold another welcoming lunch in Judge Kingham’s honour in the near future.

Dane Thornburgh

Discuss this article on the forum

QUEENS’ BIRTHDAY SILK

Aka Australia Day Silk. Promoted for services to the public other than lawyering. Normally good blokes/girls. Can usually be trusted not to go beyond their capabilities at least early on. Ironically often treated badly by Queens’ Birthday Judges.

LOG JAM SILK

Promoted because presents genuine barrier to more deserving types. Often members of esteemed Chambers or leader of vocal minorities.

SHORT TERM SILK

On a promise for judicial appointment. Usually to District Court. Will not in reality take up a spot for existing or future silk. Will enhance the status of where going and vindicate choice as silk in one usually quick step.

FADED DECORATIVE SILK

Person appointed on basis of decorative silk whose appointment falls through (or in the rare case offer is turned down — in a double switcheroo) but left with no silk’s practice and no judicial appointment.

SMALL FIRM SILK

Never briefed by large firms (thinks that is a virtue) rarely acts for same firm twice (thinks that is a virtue), often given silk for good of his clients so he/she will have a junior. Often says: “Do you have money in trust?” (thinks that is a virtue).

BIG FIRM SILK

Usually briefed by senior partners at national law firms so as to make their fees seem reasonable. Never settles until after disclosure teams have scanned all documents and then fully loaded and cross checked data base. Often has conferences in Chambers on Sundays with rare foods.

PIONEER SILK

PIONEER SILK

Early settler. Crude old fashioned methods. Rarely has conferences in Chambers on Sunday. Thinks calamari is bait. Often says: Just remind me where that is in the brief. Knows other “settlement silks” phone numbers and secretaries’ christian names by heart.

ANGRY SILK

Treats everyone as an idiot, especially instructing solicitor, junior and client. May throw telephone handset. High secretary turnover. Briefed by people of low self esteem. Rarely criticised directly. Often high fee charger. Can sometime inflame them by saying: “Oh I thought you were cross because of my work but I see you are cross because of your life”.

JUDGE WHISPERER SILK

Success inexplicable to human observation; perhaps possessed of mythical powers.

DEFENDER OF SILKS

Silk who understands generally why no more silks should be made and specifically why no more silks should be made in his/her area of practice. Vocal supporters of minority advancement and reward for public service.

‘Take Home’ Points

Remember, as a junior barrister there is only one good silk. That is the silk that gets you lots of junior briefs, does all the work and tells the solicitor you did it and still wins the case.

Past Papers

Assume that after twelve years’ admission you will be wanting silk. What should you do from the outset of your career to enhance your prospects? Include mock up of letterhead, description of extra-curricular activities, description of clothes worn whilst not in court, nor more than 600 words.

I f a person is denied committal proceedings, “the accused is denied (1) knowledge of what the Crown witnesses say on oath; (2) the opportunity of cross-examining them; (3) the opportunity of calling evidence in rebuttal; and (4) the possibility that the Magistrate will hold that there is no prima facie case or that the evidence is insufficient to put him on trial …”. (See: Barton v The Queen (1980) 147 C.L.R. 75 at p.99)

Whilst all of the above is undoubtedly correct, it does not follow that in every case oral evidence ought be called at committal nor witnesses cross-examined.

However, it is at committal stage that careful advice must be given to defendants to enable them to understand the options they have as to the future progress of their case and the consequences of the option taken.

This is so because optimum prospects of success at trial usually depend on testing evidence at committal, but equally, the best chance of securing the most favourable sentence for a defendant often involves the deliberate avoidance of oral evidence at committal.

Whether You Should Require Oral Evidence At All?

The answer to this depends upon the case you are dealing with.

If it seems likely that the matter will ultimately result in a plea of guilty in a superior Court, it may well be better to have a full hand-up committal. In some cases, the saving of every skerrick of mitigation, including saving Crown witnesses from the ordeal of giving evidence and being cross-examined at committal, may be the difference between a custodial and non-custodial sentence. Whatever the case, not putting Crown witnesses through committal proceedings should always be taken into account by a Judge in favour of the defendant when determining sentence.

This is so because a hand-up committal goes hand-in-glove with the later plea of guilty. It may demonstrate, at an early stage of the process, remorse and co-operation, and it also achieves a saving to the State. These are significant mitigating factors when it comes to sentence.

Of course, it is often difficult to assess whether or not the matter will result in a plea of guilty. One does not wish to waste mitigation and thereby fail to achieve the most favourable sentence for a defendant, should he subsequently plead guilty, by unnecessarily conducting contested committal proceedings. On the other hand, one does not wish to miss the opportunity of testing relevant witnesses at committal should the matter be going on to trial.

Notwithstanding strong cases against defendants at committal, at that early stage of the criminal justice process, before the reality of the benefits of maintaining every piece of mitigation really hits home for a defendant, some defendants will not even countenance the possibility of a plea of guilty.

Notwithstanding strong cases against defendants at committal, at that early stage of the criminal justice process, before the reality of the benefits of maintaining every piece of mitigation really hits home for a defendant, some defendants will not even countenance the possibility of a plea of guilty.

It is, of course, very difficult for defendants to make these decisions. Some defendants, though innocent, may be tempted to plead guilty and therefore have a hand-up committal in an attempt to secure the most favourable sentence. On the other hand, some defendants may have little prospect of succeeding at trial, but, for any number of reasons, they may insist on contesting committal proceedings and marching on to trial.

A lawyer can do no more than in every case explain to the client in detail the pros and cons of a hand-up committal and the pros and cons of a contested committal. It is then for the client to give instructions in relation to the conduct of the committal.

In cases of multiple charges, a defendant may contest at committal certain charges and not others. If, subsequently, those contested charges are defeated and the defendant pleads guilty to the others, no mitigation will be lost.

In some cases, a defendant may contest the severity of the charge. For example, whilst prepared to plead guilty to assault occasioning bodily harm, the defendant contests at committal the circumstances of aggravation alleged. If, subsequently, the circumstances of aggravation are defeated, the defendant will have lost no mitigation upon a plea of guilty to assault occasioning bodily harm.

Further, a defendant may test evidence at committal with a view to establishing the proper factual basis of the offence for sentence purposes. For example, the defendant may be prepared to plead guilty to dangerous driving causing death on the basis of some speed, but deny that he was travelling anywhere near the speed alleged by the pursuing police.

If ultimately the defendant is sentenced on the basis of the less serious circumstances, then, again, of course, the defendant’s mitigation remains intact.

There are two other considerations at committal stage when looking at securing the most favourable sentence for a client.

Firstly, consideration may be given to whether one should by-pass committal proceedings altogether and consent to an ex-officio indictment.

Firstly, consideration may be given to whether one should by-pass committal proceedings altogether and consent to an ex-officio indictment.

Experience suggests that this course has practical difficulties. Before an ex-officio indictment may be presented, the Crown and defence must be in agreement as to the factual basis for sentence. Logistically, it is often very difficult to achieve this agreement because the Director of Public Prosecution’s office is extremely busy and work must be prioritized. It can happen that it takes longer for a defendant to be sentenced on an ex-officio indictment than if he had proceeded through a hand-up committal.

Experience also suggests that there is not a significant advantage, if any, for the defendant at sentence in proceeding by way of an ex-officio indictment. Consenting to an ex-officio indictment is a clear indication of an early plea of guilty. But, so too is consenting to a hand-up committal followed by having the sentencing Court informed of the plea of guilty on presentation of the indictment.

Secondly, consideration may be given to pleading guilty at the committal proceedings. In my opinion, this course is open to problems. For example, once the defendant is recorded as pleading guilty to the charge it may be difficult to achieve concessions from the Crown as to the factual basis for the sentence. Or, as months pass between committal and presentation of the indictment, a defendant may change his mind as to the plea, prompted by any number of things.

In my view the safer course at committal is to advise the defendant to not enter any plea. Then, upon confirming the intention to plead guilty once the indictment has been presented, the defendant attracts the benefits resulting from an early intimation of a plea of guilty.

There is no doubt that the best chance of securing the most favourable sentence for a client involves careful advice and decision-making at the committal stage.

If it seems likely that the matter is to proceed to trial, the testing of evidence at committal is usually essential to achieving optimum prospects of success at trial.

I say “usually” because there are exceptions to requiring and testing oral evidence at committal, even when intending to go on to trial.

In some matters, for example importation of drugs, the case may depend on incontrovertible circumstances including video and telephone surveillance proving the importation of the package by the defendant. Subject to considerations of testing the validity of warrants, there may be nothing in the Crown case to contest. Rather, the guilt or otherwise of the defendant may depend upon his explanation at trial as to what the telephone conversations really meant and why the package he imported contained drugs. The explanation that he thought the package contained diamonds and not drugs has been done before both with and without success.

Again, in some cases all witnesses for the Crown may be friendly with and sympathetic to the defendant. The defence may take signed proofs of evidence from such witnesses, clarifying and qualifying their Crown statements without the need for committal proceedings. This process has the obvious advantage that the prosecution may not know about the clarifications and qualifications which these witnesses would undoubtedly give at trial.

There are also cases in which a defendant contests the charge but on the face of the police statements there is a hiatus in proof of one of the elements of the offence. If one embarks upon oral evidence, the relevant missing evidence may tumble out. The prosecutor, upon looking more closely at the brief if it is a contested matter, may take the opportunity to augment the evidence in the statements and fill the evidentiary gap. It therefore becomes tempting to have a hand-up committal and then argue on the face of the statements that the charge is not made out and have the defendant discharged at committal. However, the victory may be short-lived. The Director of Public Prosecutions may present an ex officio indictment, having secured the missing evidence. The defendant has then lost the opportunity of testing all of the relevant evidence at committal. If it is demonstrated that a defendant would suffer unfairness in not cross-examining relevant witnesses before trial, a judge would permit cross-examination on a voir dire. However, leaving aside consideration of any Crown evidence obtained after committal, it may not be easy to demonstrate unfairness in circumstances in which the defence made a tactical decision to avoid cross-examining any witness at committal.

The benefits for the defence of requiring oral evidence at committal are substantial:

(a) The defence gets to know precisely the case against the defendant. The witnesses are made to articulate in detail what they claim to have seen and heard etc. and to detail the circumstances in which they say everything occurred. Any shortcomings in what they can say about the matter become apparent. There is far greater clarity to the case than that which is described in police statements.

(b) The defence gets to see the witnesses and learn how they will perform before a jury. One learns whether a witness is likely to be flexible or likely to give no concessions to any suggestion made by the defence. This assists in determining how to cross-examine each witness before the jury.

(c) The defence learns what questions to ask at trial, and, importantly, what questions not to ask at trial. Getting a damaging response to a non-essential question from a witness in cross-examination at committal is generally not harmful to a defendant. The defence knows not to ask that question before the jury. On the other hand, if a Crown witness responds to questions in a way favourable to the defendant, one can ask those questions with safety before the jury. If the witness gives an inconsistent answer before the jury, the person’s answer at committal may be proved.

There are disadvantages for the defence in requiring oral evidence at committal:

(a) The Crown witnesses get something of a dress rehearsal before trial. It is true that some witnesses may suffer a rough cross-examination at committal and therefore be fearful of cross-examination at trial, resulting in their being less dogmatic before the jury. However, often witnesses draw strength from having survived the committal proceedings and are better prepared for cross-examination at trial. Some Crown witnesses may then present better before the jury than they did at committal.

(b) There is the potential that cross-examination at committal may inadvertently enliven a line of inquiry by the prosecution, disadvantageous to the defence and previously unknown to the prosecution.

Notwithstanding disadvantages or potential disadvantages, generally speaking, defendants who are going on to trial should undoubtedly require oral evidence at committal.

The Nature and Scope of Questioning

Questioning is usually quite unconfined (but relevant) and persistent (that does not mean repetitive) since the purpose is to know precisely what a witness will and will not say about the case. However, as referred to above, care must be taken with the questioning not to provoke a valuable line of inquiry for the prosecution. For example, in an assault case, wide cross-examination of a witness to the alleged assault may cause the witness to mention for the first time that the witness saw the defendant involved in an earlier altercation with a person other than the complainant. Or, the witness may mention for the first time that another person, previously unknown to police, also witnessed the alleged assault. The prosecution would no doubt be interested in further proofing the witness as to the defendant’s aggressive demeanour and behaviour during the day prior to the alleged assault and in proofing the other potential witness to the alleged assault.

The defence is not obliged nor expected to, and, in my view, usually should not, put the defence case or any part of it, at committal. No doubt there will be circumstances which justify exception to the rule, but they would be rare. Generally speaking, there is not only no benefit to a defendant, but there is potential damage, in broadcasting at an early stage to the prosecution and the Crown witnesses the defence case or that which the defendant says about certain parts of the Crown evidence. For a start, it gives the prosecution the opportunity to gather further evidence to rebut propositions put at committal. It also alerts the witness to what will be suggested at trial and thereby enables the witness to give a more considered response before the jury.

It is also important to remember that the conduct of committal proceedings can be revisited by the prosecution at trial. If the defence puts a proposition to a witness at committal and a different proposition is put to the witness at trial, the apparent inconsistency in instructions by the defendant to his lawyers can be explored in cross-examination of the defendant at trial.

In circumstances in which the defence believes that it has very good prospects of defeating the charge, permanently, at committal, exposing the defence case may be warranted. For example, having cross-examined a police officer to the point where he asserts without any doubt that the conversation between him and the defendant is the inculpatory conversation which he swears it to be, the playing of an audio tape of that conversation revealing nothing but exculpatory statements by the defendant, could be well justified. It must be remembered that the assessment of the credibility/reliability of a witness called at committal is “a matter which has relevance in determining whether evidence there adduced is sufficient to put an accused person on trial before a jury. One object of testing the evidence of a witness upon committal proceedings is to test the strength of the case brought against the defendant to see if it justifies putting him on trial”. (See: Purcell v Venardos (No. 2) (1997) 1 Qd.R. 317 at p.322)

In circumstances in which the defence believes that it has very good prospects of defeating the charge, permanently, at committal, exposing the defence case may be warranted. For example, having cross-examined a police officer to the point where he asserts without any doubt that the conversation between him and the defendant is the inculpatory conversation which he swears it to be, the playing of an audio tape of that conversation revealing nothing but exculpatory statements by the defendant, could be well justified. It must be remembered that the assessment of the credibility/reliability of a witness called at committal is “a matter which has relevance in determining whether evidence there adduced is sufficient to put an accused person on trial before a jury. One object of testing the evidence of a witness upon committal proceedings is to test the strength of the case brought against the defendant to see if it justifies putting him on trial”. (See: Purcell v Venardos (No. 2) (1997) 1 Qd.R. 317 at p.322)

Questioning of witnesses as to any criminal history and as to matters of credit unrelated to the circumstances of the offence is often productive. Whilst the Crown is obliged to provide criminal histories of witnesses if requested, most witnesses are unaware of this. Sometimes a witness is silly enough to deny any criminal history, or, minimise it. Of course, lawyers must be aware of and comply with Section 15A of the Evidence Act when questioning as to a person’s criminal history. Again, one must be aware of Section 15 of the Evidence Act. If the defence attacks the character of a Crown witness at trial and the defendant gives evidence at trial, the prosecution may seek leave to cross-examine the defendant as to his criminal history.

In some cases it is preferable to have relevant witnesses give full evidence at committal, rather than allow the police statements to be handed up as the evidence in chief. If witnesses are not retelling what they actually saw or heard, but advancing a fabricated or partially fabricated version of events, inconsistencies, of substance, should emerge during the criminal process. By the time of cross-examination at trial, the defence advocate will be armed with the police statement of the witness, his evidence in chief at committal, his cross-examination at committal and his evidence in chief at trial. Any inconsistencies can then be demonstrated in cross-examination before the jury.

Conclusion

Committal proceedings are held for the benefit of the defendant. Such proceedings should never be regarded by lawyers as just an easy day in Court. Properly conducted, they are invaluable to the defence. For the defence, a trial starts with the committal proceedings.

Terry Martin SC

Discuss this article on the Hearsay Forum

Letter from The Hon. Sir Gerard Brennan AC KBE

Frank Glynn Connolly is a much loved member of the Queensland Bar. Not merely because he has continued in practice into his tenth decade, nor because he is a colourful figure — sometimes colourful in dress, frequently colourful in advocacy, and very frequently colourful in language. He is appreciated because he represents the best values of the Bar and has done so from the very beginning of his practice.

Before the Second World War, Frank enrolled in Arts/Law and graduated with first class honours in English Literature from Queensland University. He temporarily diverted to Medicine. However, Max Julius spoke to him about the works of TS Eliot — then regarded as very avant-garde — and Frank decided to take the poet as the subject of a thesis. Then the war had intervened and Frank joined the 3rd Division as an anti-aircraft gunner. He finished his thesis, earned his M.A. and was commissioned. He served in Papua New Guinea. Later he volunteered for the British Army, serving in India and Malaysia. When the Pacific War ended, he was demobilized in London but then returned to complete his law degree. He graduated in 1949 and came to the Bar. But he had been captivated by the beauty and the power of language, and he continued to employ his talents in the writing of poetry which, for the most part, he has refused to publish. I imagine that, for Frank, one of the great attractions of the Bar must have been the opportunity and the ambience in which to indulge his love of the language. His literary interests were shared by his friend Austin Asche, and would have been welcomed by Kennedy Allen (whose Justices Acts became a classic), Vince Fogarty (the Balladist of the Bar) and others who delighted in the written and spoken word. Those of us who have heard Frank’s often florid eloquence as an advocate might be surprised by the disciplined elegance of his writing. A glimpse of his literary skill can be seen in two obituaries published in the 70th Anniversary book of the Law School. The lines he penned about Alexander Charles McNab and Chester James Parker are spare and moving tributes to dear friends.

Before the Second World War, Frank enrolled in Arts/Law and graduated with first class honours in English Literature from Queensland University. He temporarily diverted to Medicine. However, Max Julius spoke to him about the works of TS Eliot — then regarded as very avant-garde — and Frank decided to take the poet as the subject of a thesis. Then the war had intervened and Frank joined the 3rd Division as an anti-aircraft gunner. He finished his thesis, earned his M.A. and was commissioned. He served in Papua New Guinea. Later he volunteered for the British Army, serving in India and Malaysia. When the Pacific War ended, he was demobilized in London but then returned to complete his law degree. He graduated in 1949 and came to the Bar. But he had been captivated by the beauty and the power of language, and he continued to employ his talents in the writing of poetry which, for the most part, he has refused to publish. I imagine that, for Frank, one of the great attractions of the Bar must have been the opportunity and the ambience in which to indulge his love of the language. His literary interests were shared by his friend Austin Asche, and would have been welcomed by Kennedy Allen (whose Justices Acts became a classic), Vince Fogarty (the Balladist of the Bar) and others who delighted in the written and spoken word. Those of us who have heard Frank’s often florid eloquence as an advocate might be surprised by the disciplined elegance of his writing. A glimpse of his literary skill can be seen in two obituaries published in the 70th Anniversary book of the Law School. The lines he penned about Alexander Charles McNab and Chester James Parker are spare and moving tributes to dear friends.

Frank was taken into the Chambers of Reginald Raby Mulhall King, better known — though tautologically — as Rex King. Rex was a busy junior, later taking silk. He was a little idiosyncratic. After a wonderful party which Rex gave for the whole Bar at his Graceville home, he offered some of his guests one of his favourite records (the old graphite 78 rpm type) to chew. Brisbane dentists were surprised by the sudden appearance of an unusual substance in Barristers’ teeth! Next door to Rex on the first floor of the (very) old Inns of Court at 21 Adelaide Street was the legendary Dan Casey and the brilliant and ebullient Octy North. Frank availed himself of Dan’s advice when preparing his first criminal brief:

“Sir”, said Frank. “Don’t call me Sir,” replied Dan. “No, Sir, I won’t”, said Frank “but will you help me with this criminal brief?” “Of course, my boy! Sit down and tell me what the facts are”. “No, sir, I don’t need any help with the facts. I have read the depositions, there is a full statement in the brief and I have had a conference with the client”, Frank assured him. “Then what is the point of law, Frank?” asked Dan. “Oh,” said Frank, “I have been through Carter’s Criminal Code and all the notations to the section, so that is alright”. Dan was mystified. “Well what can I help you with?” he asked. “Sir”, said Frank “I thought you could help me with the b……t!”

In those days, every barrister’s door was open and the newcomer was welcome to go into any chambers and seek advice or, at least, stimulating conversation. The practising Bar numbered less than 70 and each Barrister knew all the others. All but a few of the Brisbane Bar had chambers in the (very) old Inns of Court at 21 Adelaide Street. It was, I suppose, something of a closed circle but the advantage to a junior barrister learning the arts and skills of advocacy were enormous and the standards of the Bar were transmitted and rigorously maintained by a kind of osmotic pressure. Frank’s innate integrity was of a piece with the standards of the Bar from which he has never departed.

In those days, every barrister’s door was open and the newcomer was welcome to go into any chambers and seek advice or, at least, stimulating conversation. The practising Bar numbered less than 70 and each Barrister knew all the others. All but a few of the Brisbane Bar had chambers in the (very) old Inns of Court at 21 Adelaide Street. It was, I suppose, something of a closed circle but the advantage to a junior barrister learning the arts and skills of advocacy were enormous and the standards of the Bar were transmitted and rigorously maintained by a kind of osmotic pressure. Frank’s innate integrity was of a piece with the standards of the Bar from which he has never departed.

In the late 40’s and early 50’s, some of the bread and butter of the junior Bar were briefs for plaintiffs in undefended divorces, at a fairly standard fee of 10 guineas. This was before the introduction of “no fault” divorce. Frank did not believe in divorce. So, despite the financial loss, Frank declined to accept briefs to sever the marriage bond. In time, other briefs arrived and he was able to leave Rex’s chambers and move up to a vacant room on the third floor. It was a small and cohesive group and Frank’s ebullient presence contributed greatly to the friendships that were formed. His practice grew as his devoted, often passionate, advocacy was much respected. Hyperbole there may have been, but never a submission that was dishonourable. There were, of course, many occasions when Frank assured us that he was acting for the most misunderstood and decent client who had ever been wrongly prosecuted or sued!