Results of the Straw Poll

Should we do away with wigs and robes?

The results were as follows:

“No” – 144 responses – 77.8%

“Yes” – 41 responses – 22.2%

To the 185 members who responded – thank you.

The average barrister is male, in their mid-40’s and has been at the Bar for 10 or more years having started in their mid-30’s. They practice from chambers in the Brisbane CBD.

I don’t quite make average as I was admitted at 24 and have practiced mainly at regional bars. I am also fortunate enough to have spent some time in my legal career outside the private Bar both in government service and academia. It was these experiences that gave me an interest in demographics and led me to question how a professional organisation like the Bar should be responding to our aging membership. How can we remain an attractive profession for younger people and how do we retain our longer serving members as the Baby Boomers approach retirement?

The ever efficient Bar Association staff have kindly provided me the data for analysis (with identifying particulars removed). Time invested in learning IT skills enabled me to extract some basic facts and graph them.1 I will mostly let the findings speak for themselves but there are some interesting and perhaps unexpected results.

- There appears to be a significant number of practitioners approaching the time when most barristers retire with another ‘hump’ following in 10 years.

- Barristers who have Chambers outside of Brisbane account for about 13%.

- About 12% of all barristers are not in a Chambers in a major court town near the registry.

- Female barristers still make up only about 16% of the total.

- The Bar remains popular with as many people joining each year as ever.

- Members leave the profession at a fairly steady rate after their second year.

- Most of the new members join in their thirties suggesting they have had earlier work experiences, perhaps as solicitors.

- Silks are admitted as Juniors, on average, 7 years younger than the average Junior who is still practicing as such.

| Counsel |

All |

Male |

Female |

| Junior |

782 |

646 |

136 |

| Senior |

59 |

56 |

3 |

| Queens |

31 |

31 |

0 |

| Totals |

872 |

733 |

139 |

| Class |

|

| A Class |

757 |

| B Class |

115 |

| |

872 |

| Chambers |

|

| Blank |

19 |

| Brisbane |

648 |

| Cairns |

24 |

| Ipswich |

10 |

| Mackay |

6 |

| Maroochydore |

14 |

| Rockhampton |

10 |

| Southport |

20 |

| Toowoomba |

5 |

| Townsville |

24 |

| Other |

92 |

| Average Age at Call |

| All |

33 |

| Men |

33 |

| Women |

34 |

| Junior |

34 |

| Non-Juniors |

26 |

| Average Age |

| All |

46 |

| Men |

48 |

| Women |

42 |

| Junior |

46 |

| Non-Juniors |

54 |

| Seniority Group |

All |

Male |

Female |

| 1-3 |

151 |

38 |

113 |

| 3-10 |

236 |

53 |

183 |

| 10+ |

468 |

46 |

422 |

| Unknown |

17 |

2 |

15 |

| |

872 |

139 |

733 |

Caveat Lector

“Lies, damned lies, and statistics” was a catchphrase of Benjamin D’Israeli. It should be borne in mind that we do not have critical data to validate many of the theories that the statistics suggest. In particular there is no way at present of comparing admissions during a calendar year to people now holding membership. This means any apparent drop in numbers such as women in their 8-11th years of admission could be because very few joined our ranks 8-11 years ago or because that age group have temporarily left full-time practice.

It is also difficult to account for the large numbers of barristers in government or corporate employ (sometimes without individual practicing certificates) or indeed those on the rolls who do not practice extensively.

It is also difficult to account for the large numbers of barristers in government or corporate employ (sometimes without individual practicing certificates) or indeed those on the rolls who do not practice extensively.

Equally, Chambers addresses are a poor way method of distinguishing members with more than one chambers, those practicing in a city without a Registry, those working from home, door tenants and squatters.

I propose to re-examine the data for a future edition of Hearsay in relation to the major areas of practice nominated compared to Gender, Location, Age and Years at the Bar. If any member has a suggestion for other statistical research, please contact me directly.

Andrew Sinclair

Andrew.Sinclair@innsofcourtsc.com.au

Telephone (07) 5479 2940

Comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum

Endnote

- For the obsessive footnote readers, data was extracted in CSV format, manipulated with

PERL and graphed in Excel.

Supreme Court Notification – Commercial List and Supervised Case List Manager Brisbane

Martin Moynihan AO, Senior Judge Administrator of the Supreme Court of Queensland advises members that as of 25 July 2007, the Commerical List Manager and Supervised Case List Manager is Elizabeth Rosenthal. To download a copy of the Notification and contact details for Ms Rosenthal, CLICK HERE.

Supreme Court Notification – Confiscation of Profits Application

To download a copy of the Supreme Court Notification – Confiscation of Profits Application dated 1 August 2007, CLICK HERE.

Bar Council Election of Office Bearers

Members are advised that the following office bearers were elected at the meeeting of the Bar Council held on 17 July 2007:

Vice President – Michael Stewart SC

Honorary Secretary – Roger Traves SC

Hugh Fraser QC fills the position of President caused by the elevation of Martin Daubney SC to the Supreme Court.

Current Civil Hearing Dates – Brisbane Supreme Court

To view an electronic table of available civil hearing dates for the Brisbane Supreme Court, CLICK HERE. Available dates are highlighted in green and updated hourly.

Practice Directions – Magistrates Court of Queensland

To download a copy of Practice Direction No.5 of 2007 – Uniform Civil Procedure Procedure Rules 1999, CLICK HERE.

To download a copy of Practice Direction No.6 of 2007 – Costs Assessment: Interim Arrangements, CLICK HERE.

To download a copy of Practice Direction No.7 of 2007 – Committals and Ex Officio Sentences, CLICK HERE.

Practice Direction No. 8 of 2007 – Supreme Court of Queensland

To download a copy of Practice Direction No.8 – Private Audio Recording of Proceedings – Supreme Court, CLICK HERE.

Interim Register of Cost Assessors

To download a copy of the Registry Information Sheet – Interim Register of Cost Assessors as of 16 August 2007, CLICK HERE.

Valedictory Ceremony for the Honourable Justice Moynihan AO – 24 August 2007

A Valedictory Ceremony to mark the retirement of the Honourable Justice Moynihan AO will be held in the Banco Court at 9.15 am on 24 August 2007. Black robes are to be worn. The Honourable Justice Byrne RFD has been appointed Seniour Judge Administrator.

Criminal Law Conference – 24 August 2007

The Queensland Law Society Criminal Law Conference 2007 will take place on 24 August at the Royal on the Park Hotel, Brisbane. The topics to be addressed include a two-part concurrent session which will look at pleas of guilty and sentencing, a session devoted to emerging forensic technologies and a session discussing document management in complex criminal trials. Attendees will be awarded 6 CPD points. More information and online registration is available at www.qls.com.au

Legal Secretaries & Personal/Executive Assistants Summit – 24 August 2007

The opening plenary session of the Queensland Law Society Legal Secretaries & Personal/Executive Assistants Summit 2007 will address legal support staff as the backbone of the well functioning legal office. Marie Bergwever, Executive Assistant to the Hon Chief Justice Paul de Jersey AC will make the closing comments and the sessions will include practical workshops covering topics such as managing workflow, avoiding communication breakdown, managing ethically difficult situations and accounting. The conference will take place at the QUT Gardens Theatre Complex, Brisbane on 24 August 2007. More information and online registration is available at www.qls.com.au

Rule of Law Conference – 31 August – 1 September 2007

The Rule of Law Conference – The Challenges of a Changing World will take place in the Banco Court, Supreme Court of Queensland, Brisbane on 31 August and 1 September 2007. Attendees will be awarded 1 CPD point per hour of attendance. For more information please contact Ms Gwen Fryer of the Law Council of Australia on ()2) 6246 3715 or email gwen.fryer@lawcouncil.asn.au

Second National Indigenous Legal Conference – 14-15 September 2007

“40 Years Since the Referendum” is the theme of the Second National Indigenous Legal Conference which will take place in the Banco Court, Supreme Court of Queensland, Brisbane on 14 – 15 September 2007. Topics will include running a successful Native Title case, intellectual property, governance in indigenous communities, Aboriginal deaths in custody – an update with emphasis on the Palm Island case, Tasmanian apology and compensation and United Nations and human rights developments. For more information please contact Shayne Goodwin at the Continuing Professional Development office on (07) 3238 5109 or email shaynegoodwin@qldbar.asn.au

Wine Me and Timmys Restaurant – Degustation Evenings – 28, 29 & 30 August 2007

Wine Me, in association with Timmys Restaurant, invites members to attend a degustation evening which will present a guided tasting of great wines teamed with four sumptuous courses by renowned chef Timmy. The event will take place at Timmy’s Restaurant, Southbank. To make a reservation contact Glen Robert on 0418 190 104 or email glen@bentsroadwinery.com

The Duties and Responsibilities of an Expert Witness

The duties and responsibilities of an expert witness in Queensland court proceedings will depend upon when and how the expert came to be appointed. The 2004 amendments to the Queensland Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (“UCPR”) have meant that there are various categories of experts:

- Where an expert has been appointed prior to 2 July 2004 the evidence of that expert is not subject to the new rules;1

- Experts appointed in minor claims in the Magistrates Court are excluded from the new rules entirely;2

- Experts appointed after 2 July 2004 in Magistrates Court proceedings (excluding minor claims), and in District Court proceedings, are subject to the general duties and obligations in UCPR Chapter 11, Part 5, Divisions 1 and 2,3 but are not subject to Division 3 (experts appointed jointly by the parties or by the court);4

- Experts appointed by the parties or by the court5 before any court proceedings are instituted can be appointed under the new regime in Part 5 Division 4;

- In Supreme Court proceedings experts are to be appointed pursuant to the new regime in Part 5 Division 3.6

Experts Appointed Outside the New Part 5 Regime

Experts appointed outside the regime in UCPR Chapter 11, Part 5 [ie. categories (a) and (b) above] are subject to the pre-existing law. Under that system, in the rare cases where an expert is appointed by the court, the expert is required to enquire into a specific issue and report to the court.7 In the vast majority of cases the expert is retained by a party to the litigation and is obliged to follow the instructions of that party and to report to that party. In Queensland, if the expert has produced a written report for a party, that party is obliged to disclose the expert’s report.8

In recent years many practitioners in Queensland, perhaps conscious of something of a backlash against partisan expert evidence,9 adopted a practice of asking their expert witnesses to read and follow the instructions in the Federal Court’s Practice Direction: Guidelines for Expert Witnesses10

Any expert proposed to be called in Federal Court proceedings11 must be given those guidelines. The Federal Court guidelines specify that:

- An expert witness has an overriding duty to assist the Court on matters relevant to the expert’s area of expertise.

- An expert witness is not an advocate for a party.

- An expert witness’s paramount duty is to the Court and not to the person retaining the expert.

Experts Appointed Within the Part 5 Regime

Experts retained under the new regime in Part 5 [ie. categories (c), (d) and (e) above] are subject to a duty similar to that specified in the Federal Court guidelines, namely:

- A witness giving evidence in a proceeding as an expert has a duty to assist the court.

- The duty overrides any obligation the witness may have to any party to the proceeding or to any person who is liable for the expert’s fee or expenses.12

Both the Federal Court guidelines and the UCPR Part 5 regime specify the particular requirements of the expert’s report. The rules are similar and require detail of the expert’s qualifications, the facts relied on, the expert’s assumptions, the literature relied on, and the expert’s opinion and reasons for that opinion.

However, the mode of imposition of the expert’s duties and obligations in preparing the report differs from Court to Court. The Federal Court regime merely requires the expert to be given a copy of the Federal Court Guidelines for Expert Witnesses. The Supreme Court’s UCPR Part 5 regime expressly imposes the duties on the expert, and specifies the requirements of the report, and requires the expert to confirm, at the end of his report, that he understands his duty.

Ensuring the Expert is Independent

The Federal Court’s approach to ensuring that the expert is independent is to require the expert to be handed the Federal Court guidelines which explicitly state that the expert’s duty is to the Court and not to the party.

My experience is that experts are often relieved to have their duty explicitly stated and to be told that they must assist the Court by candidly stating their opinion ‘warts and all’. Such a step often dissolves any doubts or confusion the expert might have entertained.

However, the Part 5 regime is far more pessimistic. First, the UCPR Chapter 11 Part 5 regime is more direct than its Federal Court counterpart. Part 5 imposes on the expert a positive duty to assist the Court and states that the duty to assist the Court is to override any duty to a party.

A matter of perhaps faint curiosity is how that duty might be enforced. A party who ascertains that an expert is in breach of that duty might be hard-pressed to directly seek any remedies. The duty is expressed to be owed to the Court. And, if the court finds an expert in breach of the UCPR duty, there are likely to be few remedies open to it.13

Second, Part 5 requires that Supreme Court litigants either agree to appoint a joint expert or to make an application for a court-appointed expert.14

The intention of Part 5 seems to be to restrict litigants to those two choices (i.e. joint expert or court appointed expert) with the only other possibility being an expert appointed by the Court on its own initiative.15

The rules do not expressly exclude the possibility of the parties separately retaining their own experts. Probably the Court retains the discretion to permit separately retained experts.16 However, the intention of Part 5 is certainly to require the parties to either agree on a joint expert or to apply for a court appointed expert. The rules, deliberately, do not explicitly leave open to the parties a right to retain their own experts.

In summary, the rules establish a presumption in favour of the appointment of a single expert, either by agreement of the parties, or by order of the Court.17

The Court’s desire to have some control over the process of appointment of experts is also evident from Practice Direction No. 2 of 2005 which specifies that, as soon as it is apparent to a party that expert evidence on a substantial issue will be called at the trial or hearing, that party must file an application for directions.18

The issue of mild interest here is whether a system, which requires either one joint expert, or one court appointed expert, will succeed in producing an independent expert. The NSW Law Reform Commission19 identified 3 types of bias in expert witnesses:

- Pre-Conceptions Bias.20 Experts, like many others in the community, including judges, will have assumptions, beliefs and values which may influence the expert’s opinions. The expert may have views on matters that are controversial within their profession.21 Sometimes, for example, the expert may feel inhibited by professional solidarity from taking a view adverse to a defendant who is a professional colleague.22

- Selection Bias: Litigants naturally choose, as their expert witnesses, persons whose views they know or expect will support their case.23 The expert may well give careful and honest evidence, but has been selectively chosen.24

- Adversarial Bias: An expert retained by one party may deliberately tailor evidence to support his or her client. Or, more likely, an expert may be guilty of unconscious partisanship, that is, be influenced by the situation to give evidence in a way what supports the client.25

How can the Court ensure that the expert is independent and that the expert evidence is unaffected by those types of bias?

One method is to ensure that the expert properly understands their role and the need for the expert to give a fair and independent opinion. The Federal Court guidelines adopt that approach. Similarly with codes of conduct for expert witnesses.26

The Hon. Justice Garry Downes,28 President of the Australian Administrative Appeals Tribunal, takes the view that, the experience of the Court is that whilst experts generally expose the matters which support the hypothesis which most favours the party calling them, with very few exceptions, expert witnesses do not deliberately mould their evidence to suit the case of the party calling them. His Honour sees great value in the traditional approach of exposing different expert points of view for evaluation by the Judge.27

The Hon. Justice Geoffrey Davies takes a different view. He takes the view that polarisation and adversarial bias are so endemic as to require a more radical solution.29 Hence the new Queensland rules in Chapter 11 Part 5 of the UCPR which are unique in Australia.

It is worth reviewing the impact of the new rules in UCPR Chapter 11 Part 5.

Reviewing the Impact of the New UCPR Regime

As has been mentioned, Chapter 11 Part 5 requires that Supreme Court litigants either agree to appoint a joint expert or make an application for a court-appointed expert. As mentioned there is still a possibility of the parties appointing separate experts, but the rules presume the appointment of a single expert.

Does the UCPR’s presumption in favour of the appointment of a single expert eradicate or reduce the three different types of bias?

Pre-Conceptions Bias

Pre-Conceptions Bias

Undoubtedly, having a single expert on an issue will not remove ‘pre-conceptions bias’. It is probable that a regime which favours the appointment of a single expert may accentuate the problem of pre-conceptions bias because of the risk that the Court will hear the perhaps eccentric views of one expert without having the opportunity to have those views balanced.30 The use of one expert does not guarantee that that expert’s views will be mainstream or moderate.31

The result of a system which promotes single experts may be to increase rather than decrease the importance of professional experts. An expert who is the only expert on an issue is likely to be accepted because there is no contrary view. So, a system which promotes the use of single experts may accentuate the problem of pre-conceptions bias with the consequent peril to a just result in the litigation.

Selection Bias

The appointment of a single expert, whether chosen by the parties or appointed by the Court, does not necessarily solve the problem of ‘selection bias’. It is true that the parties cannot unilaterally ‘shop around’ for an expert whose views suit them. However, there are many hurdles before one could be confident that a suitable and independent joint expert has been appointed.

The first hurdle is that the parties have to agree on a joint expert. It is possible that the parties, and their lawyers, will have similar knowledge of an expert’s industry or profession and will be able to agree on an appropriately qualified joint expert. However, if the parties or their lawyers have unequal knowledge about the relevant discipline, or perhaps even unequal diligence, the parties may agree to a joint expert who has firm views one way on a genuine controversy within the expert’s discipline.

A party may ultimately regret agreeing to an expert who has decidedly adverse views one way on matters which are the subject of genuine controversy.

Now to the second hurdle. If the parties cannot agree on an expert, how does the Court choose between potential experts before they give any evidence?32

Under the old system, the Court chose between the evidence of different experts based on their reports and their evidence. Under the new system, if the parties cannot agree on a single joint expert, the Court must decide which expert is to be retained. UCPR 429I(2) and 429J(2) require that each party nominate at least three experts. How does the Court choose between, possibly, as many as 6 different experts?

In those cases where the parties cannot agree on a single expert, the Court may be faced with the crushing burden of choosing between different single experts proposed by the litigants and having little more to go on that their CVs. It is obviously unwise for the court to choose the most senior expert,33 or the expert with the most impressive CV,34 or even to make a random choice. There is no easy way to resolve this conflict. In some cases, faced with this dilemma, the court may opt to let each party choose their own expert.

The third hurdle is that sometimes identifying the appropriate expert is difficult.

Industries and professions are different. In some fields there are many competent and experienced experts to choose from. In others, there are very few. In some specialised fields there may be only two, perhaps only one, genuine expert in the field who can speak with authority. Thus, the requirements in UCPR 429I(2) and 429J(2) that the applicant for a court-appointed expert must name at least three experts maybe a little unrealistic.

Commercial litigation lawyers will be familiar with the difficulties in trying to find an appropriate expert in a particular field. It often requires considerable research and some dedication. Finding the appropriate area of expertise can often involve dialogue with a number of experts in related disciplines. When he or she is identified, the expert in a particular field may be interstate, or overseas, and may not be willing to give evidence.

In my view, it is unreasonable to expect that the Courts should or have the resources to undertake the burden of identifying, retaining and briefing appropriate experts. The writer has been unable to find any instances of the Supreme Court appointing a single expert on its own initiative35 and no cases can be found where a single expert has been appointed over the objections of a party.

So, if the parties cannot agree, and the court does not itself undertake the task, choosing an expert from competing candidates proposed by the various litigants may be as onerous as choosing between competing expert testimony.

Instances of the Queensland Supreme Court appointing an agreed single expert are rare. It is difficult to find proper data on this. There are no reported decisions which address the issue.

However, in other jurisdictions the anecdotal evidence is that the use of single joint experts seems to be working well in that judges, lawyers and parties have displayed a willingness to use single experts, especially in matters that do not involve substantial amounts and where the issues are relatively uncontroversial.36

One suspects that, once some initial resistance to the concept is overcome, jointly appointed experts will become relatively common, but not a universal solution.

Adversarial Bias

The appointment of a single expert will, undoubtedly, solve the problem of adversarial bias. An expert appointed by the parties jointly, or appointed by the Court, is unlikely to deliberately, or even unintentionally, tailor his or her evidence to suit one or other party. Ensuring that the expert has the correct independent approach to his or her expert evidence is a significant advantage. However, at what price has the adversarial bias been eradicated?

No doubt the use of a single expert witness makes the judge’s task easier. Viewed from that standpoint, the preference for a single expert is likely to be a resounding success. In a recent Land and Resources Tribunal case, Re Brisbane Petroleum NL & Silverback Properties Pty Ltd,37 for example, the Tribunal appointed a single valuer, who assessed the appropriate compensation at $783.46 per year. The Tribunal determined the appropriate compensation at $783.46 per year.

If the object of our judicial system were efficiency; that result was efficient. The Land and Resources Tribunal only had to choose between an annual payment or a lump sum.

But the purpose of the court rules is more than to merely to achieve an efficient and expeditious resolution.38 An important goal is to achieve a just resolution. No doubt the efficient decisions reached by relying on a single expert will often also be just decisions. But I share the discomfort with a single expert system expressed by Justice Downes:

“However, in cases where there is an issue in a field of expertise and there is only one expert witness the requirement to expose criteria to enable a conclusion to be evaluated (by the judge) seems somewhat pointless when there is no alternative opinion available.” 39

His Honour continued:

“I am conscious that there are emerging reports, both in England and Australia, that single expert evidence is working well. That is not surprising. The evidence will certainly be given efficiently. The task of the judge will be easier. The problem is that there is no way of testing whether the conclusions are correct. By definition there is nothing to test the expert evidence against. That seems to me to involve the rejection of one of the fundamental benefits of our system of justice.” 40

One of the few Queensland Supreme Court cases where a single expert was appointed is NFO v PFA.41 In that case Mullins J made a consent order appointing a single expert valuer under UCPR 429I. Apparently neither party was satisfied with the single expert’s valuation because both counsel cross-examined that expert. One party was given the leave of the court to call further evidence from another expert.

Ultimately, in deciding the case, Her Honour generally preferred the evidence of the ‘single’ expert but allowance was made for other factors and to some extent the value determined by the ‘single’ expert was qualified. It is not clear from the report but presumably those qualifications were made by reason of the matters raised by the further valuation evidence.

A comparison of Re Brisbane Petroleum & Silverback Properties42 and NFO v PFA43 is interesting. Both were valuation cases where there were orders requiring a single expert. In the Tribunal case, where no other evidence was called, the single expert valuer’s evidence was accepted exactly and without qualification. In the Supreme Court case further evidence was allowed and the acceptance of the evidence of the ‘single’ expert was a qualified acceptance.

The other moderately interesting point about NFO v PFA is that it raised the issue of when parties ought to be permitted to tender additional expert evidence despite an agreed or court appointed single expert. If a party has separately retained his own expert and that expert entertains doubts about the single expert’s opinion, should that party be able to tender that additional evidence?

The burden of deciding whether to permit further evidence will fall on the trial judge. If such an application were made the competing principles are likely to be these:

- the rules presume that expert evidence will only be given by a single expert and so the Court ought not lightly allow the parties to, in effect, return to the old system with its disadvantage of competing partisan evidence;

- consistently with the principles of natural justice, a party who challenges the evidence of a single expert should not be lightly refused the opportunity to adduce evidence which contradicts the single expert.

Understanding the Expert Report

The cost savings in having a single expert may well be illusory. To understand and test the views of the ‘single’ expert, litigants may retain their own experts. That may lead to the engagement of 3 experts rather than a single expert.

It is true that in some cases the task of even understanding expert evidence is fraught and time-consuming. But having one expert does not solve that problem. It does mean that the conclusions of the single expert will not be tested. They may be beyond challenge; they may not.

Different Schools of Thought

Where, in a particular area of expertise, there are different schools of thought, or if the expert evidence will be at the cutting edge of research in a field, the use of a single expert may be a distinct disadvantage.

The NSW Law Reform Commission addressed that issue:

“7.29 It is also sometimes objected that the use of joint expert witnesses can lead to injustice where the expert issues are subject to legitimate differences of opinion, or schools of thought, among professionals in the field. This issue pertains to cases that may involve a dispute as to the method chosen, from a number of equally accepted methods, to accomplish a particular task (for example the valuation of a business). Alternatively (but more rarely) there may be cases where the issue in question is itself novel and the subject of intense debate within that particular field of expertise. In such cases, it is argued, the use of a joint expert witness would select out other legitimate views that the court should hear if it is to reach a just determination.

7.30 In the Commission’s view, this is an important point, but it is an objection to the appointment of a joint expert witness in those cases, not an objection to the court having the option of a joint expert witness in appropriate cases. Lord Woolf recognised this problem and conceded, that for some cases, including those involving issues on which “there are several tenable schools of thought, or where the boundaries of knowledge are being extended”, the oral cross-examination of opposing experts selected by the parties may be the best way of producing a just result.” 44

There are, therefore, dangers in retaining a single expert which ought to be recognised. In some cases, a single expert will be appropriate. In other cases, “a better result will flow from a diversity of expert opinion”.45

It follows that, in my opinion, the Queensland UCPR’s presumption in favour of a single expert is a system which promotes efficiency in decision-making but does so at some peril to the goal of achieving a just result.

An Advantage of Single Experts

Before leaving the topic of adversarial bias it is important to mention that there is one distinct advantage in the parties or the Court engaging a single expert.

That distinct advantage is that some illusory disputes are avoided. Let me explain.

Where two or more litigants retain experts one often finds that their reports are not directly contradictory. It frequently occurs that the expert reports pass each other like ships in the night. The result is that when they meet pursuant to a court order directing that the experts confer,46 or even in the more formal setting of a ‘hot tub’,47 there are often many acres of common ground.

The cause of differing expert opinions can often be traced to:

- experts being briefed with different facts upon which their opinion is based;

- experts being asked different questions (and so leading to different answers).

Typically, an expert accountant asked to give an opinion on a loss by a litigant will be provided with one set of documents, figures and projections and will be asked to assess the loss on a specific basis. One can almost guarantee that the expert accountant retained by the other litigant will not be given the same documents, figures and projections and will not be asked the same question. So, it is not surprising that the two expert accountants, sent different briefs and asked different questions, will arrive at divergent opinions.

A system which promotes the use of single experts will avoid those illusory disputes.

Of course, even if there are two or more experts in a particular discipline, steps can be taken to avoid illusory disputes. Having the parties, well in advance of trial, agree on a brief for the expert or experts, and on the questions to be put to an expert or experts, will often avoid illusory disputes which arise because their opinions are based on a different factual context and because they are asked different questions.

A Better System

So the UCPR Part 5 regime favours the appointment of a single expert. Far better, in my (perhaps inexpert) opinion, would be a system which did not favour a single expert but instead required the parties and the Court, at an early stage in the litigation, to consider whether the proceedings are an appropriate case for a single expert, or a number of experts, and the terms and content of their brief, and the questions for the expert. That, no doubt, is the object of and merit in Supreme Court Practice Direction No. 2 of 2005.48

In deciding whether to retain a single expert, and as a part of case management, the Court and the parties need to consider these factors:

- What are the issues which call for expert opinion?

- In particular,

- Is the issue proposed for expert evidence a matter of measurement or assessment which can either be agreed by the parties or be measured or assessed by an agreed single expert?

- Does the issue involve two (or more) schools of thought and is that expert evidence better presented by a single expert or two (or more) experts?

- Does the issue for expert evidence involve a novel area of expertise or is the expert likely to be giving evidence at the ‘cutting edge’ of research?

- Is there a suitable expert in the particular discipline? For example, is the issue one which routinely falls within the expertise of a number of experts in a discipline? Or, is there a need to seek a particular, highly qualified or authoritative expert?

- Is the question for the expert (or experts) agreed? Or can it be agreed?

- Are the parties agreed on the ‘brief’ to be sent to the expert? Can they agree?

- Are there prospects of the parties agreeing on those matters, or is the burden of attempting to agree those matters likely to outweigh the cost of the parties retaining their own experts?

- What are the likely costs and delays of the alternatives?

So, as is often the case, the better solution is not to adopt a single solution but to arm the court with different weapons for different situations. The use of a single expert is one weapon but it needs to be handled with some care.

Paul Freeburn SC

Comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum

Endnotes

- UCPR 996.

- UCPR 424(2).

- UCPR 423 and 424.

- UCPR 429E.

- Note that, in advance of any proceedings, the appointment of the expert can occur by the disputants jointly or by the Supreme Court on application: UCPR 429Q, 429R and 429S.

- As will be discussed later, there is almost certainly a further category of experts who have been appointed by the parties after 2 July 2004 but are appointed outside the regime in Part 5, Divisions 3 and 4.

- See the former UCPR 425.

- The UCPR provides that an expert report is not privileged from disclosure: UCPR 212(2); Interchase Corp Ltd (In Liq) v Grosvenor Hill (Qld) Pty Ltd (No. 1) [1999] 1 Qd R 141. The obligation to disclose the report is specified in UCPR 429. See the discussion in section G below.

- See, for example, the court’s outrage at the disgraceful conduct of the expert in “The Ikanan Reefer” [1993] 20 FSR 563; The NSW Law Reform Commission, in its Report 109: Expert Witnesses (June 2005) records concern about the use of partisan expert evidence from the mid-19th century: see pages 18 — 22.

- Federal Court Practice Direction — 15 September 1998.

- As has been mentioned, the guidelines were frequently used in non-Federal Court proceedings. Other common law jurisdictions have adopted similar guidelines: see, for example, Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW), Schedule 7 (which superseded a similar code in Pt 36 rule 13C and schedule K).

- UCPR 426.

- This issue is beyond the scope of this paper. Plainly the court has power to control its own processes. That may or may not include a capacity to punish for breach of duties imposed by UCPR. One possibility would be for the court to make an order under UCPR Ch 20.

- See UCPR 429G.

- UCPR 429G(3), 429J.

- See UCPR 423(d) which contemplates multiple experts on one issue. The Court’s power to give directions would also, it seems, contemplate a power to direct separate experts.

- NSW Law Reform Commission Report 109: Expert Witnesses (June 2005) at page 52.

- Paragraph 5 of Supreme Court Practice Direction No. 2 of 2005. That paragraph is specified as not applying to proceedings to which the Motor Accident Insurance Act 1994, or Workcover legislation applies.

- Report 109: Expert Witnesses (June 2005) at page 70 and following.

- This is not the expression used by the NSW Law Reform Commission but it is a useful compendium. The categories used by the Commission are also slightly different.

- Report 109 (supra) at p 70.

- Report 109 at p71 (Luckily this is a ‘bias’ which has rarely inhibited lawyers).

- A personal injuries plaintiff is unlikely to choose an expert medical practitioner from the “usual panel of doctors who think you can do a full week’s work without any arms or legs”: Report 109 at p 21; Vakauta v Kelly (1989) 167 CLR 568 (Toohey J quoting the trial judge).

- See Report 109 at p 74. Note also the frequent practice of lawyers to obtain an expert’s views orally and, only if favourable, to ask the expert to commit his views to a written report.

- As to the unconscious incentive to tailor reports: see G L Davies , “The Reality of Civil Justice Report” paper, 20th AIJA Annual Conference (Brisbane, 12-14 July 2002); Report 109 at p 73.

- See, for example, Schedule 7 to the NSW UCPR.

- Downes, “Expert Evidence: The Value of Single or Court-Appointed Experts”, Aust. Institute of Judicial Administration Expert Evidence Seminar, Melb. 11 November 2005, at page 3.

- Justice Davies was a member of the Queensland Court of Appeal from 1991 to 2005.

- Davies, ‘Court Appointed Experts’ QUT Law & Justice Journal (2005) vol. 5 No. 1.

- An example of the ‘balancing’ of one expert’s opinion is provided by NFO v PFA [2005] QSC 176 — a case which is discussed below.

- cf Report 109 at pp 23-4.

- Choosing experts by reference to their CVs is hardly more likely to produce a just result.

- Seniority is not necessarily a useful way of resolving differing viewpoints.

- Some of the most impressive experts possess quite modest CVs.

- UCPR 429G(3); 429J; note however that the Land & Resources Tribunal seems to appoint experts on its own initiative: see Re Brisbane Petroleum NL & Silverback Properties Pty Ltd [2004] QLRT 145.

- Report 109 at pp 106-7. Single experts are frequently used in specialist jurisdictions such as the Land and Resources Tribunal of Queensland (e.g. Re Brisbane Petroleum NL & Silverback Properties Pty Ltd [2004] QLRT 145), and the Consumer Tribunal — Building List.

- [2004] QLRT 145.

- See UCPR 5.

- Downes (supra) at p 4.

- Ibid, at 6-7.

- [2005] QSC 176.

- (supra), [2004] QLRT 145.

- (supra), [2005] QSC 176.

- Report 109 at p 115.

- Downes (supra) at 5.

- See UCPR 429B.

- The ‘hot tub’ is a concept whereby all of the experts on the same question give their evidence at the same time, and can ask each other questions. Report 109 (supra) at 32-33 comments that the procedure is used in the Federal Court and in the NSW Land and Environment Court. For a discussion of the process see Report 109 at pages 97-99. A case where the process was used in Walker Corporation Pty Limited v Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority [2004] NSWLEC 315.

- See above, particularly page 4 and footnote 18.

The ‘Better Super’ reforms introduced by the Federal Government have certainly bolstered the position of superannuation as the long-term savings vehicle of choice for Australians.

Indeed, one of the biggest changes to superannuation has been to withdrawals from taxed super funds (such as legalsuper), which are now tax-free after age 60 (whether paid as a pension or lump sum). With contributions to superannuation taxed at a maximum of 15 per cent, it is difficult to beat super as a tax-effective savings vehicle over the long term.

For employees, one of the most tax-effective ways to take advantage of the new rules is to invest into superannuation through salary sacrifice.

Salary sacrifice is giving up part of your pay packet and directing the selected amount into your super fund. Salary sacrifice contributions are taxed at 15 per cent; for many employees this rate of tax is far below that applied when wages are paid directly into their pocket. The following table explains this further.

|

Every dollar of taxable income

in this range:

|

paid into your pocket,

is taxed at:

|

or ‘sacrificed’ into super,

is taxed at: |

|

$30,001 – $75,000

|

30% |

15%

|

|

$75,001 – $150,000

|

40%

|

15%

|

|

$150,000 +

|

45%

|

15%

|

Employees on higher incomes, like many lawyers, are often in a better position to take advantage of salary sacrificing than others. They can afford to sacrifice a portion of their income, taking advantage of the low tax rate, without greatly affecting their lifestyle.

However, salary sacrifice remains largely untouched by recent reforms. Unlike other areas of superannuation that tend to be governed by numerous and complex regulations, salary sacrifice is covered by little regulation. Traditionally, salary sacrifice has tended to be covered in awards and industrial agreements. This vacuum has put much of the control over salary sacrifice arrangements into the hands of employers.

One of the most fundamental areas not covered by legislation is when employers should provide salary sacrifice. Employers are not obligated to make salary sacrifice available to their employees, and many Australians are unable to take better advantage of the super reforms. According to Mercer Human Resources Consulting, about 50 per cent of wage earners and 20 per cent of salaried workers are currently blocked by their employers from salary sacrificing.

When salary sacrifice is offered a lack of legislation governing the way it is applied has created an uneven and sometimes unfair playing field.

While salary sacrifice is supposed to be about employees deciding what to do with their income, employers currently make the key decisions about any income their employees elect to salary sacrifice.

For instance, employers have flexibility over when they pay salary sacrificed income into an employee’s super fund. Over the long term this delay can have a significant effect on the value of employees’ super fund balances.

Employers are also able to decide whether to calculate their Superannuation Guarantee (SG) obligation based on employees’ pre- or post-salary sacrifice earnings. For instance if an employee earning $80,000 decides to sacrifice an additional $5,000 into their superannuation, the employer is by law allowed to calculate their 9% SG contribution based on the reduced $75,000 salary and not the employee’s gross salary of $80,000.

Employers also elect whether to use salary sacrifice contributions to reduce their obligation to pay the 9% SG. An extreme example would be the case of an employee who salary sacrifices 9% of their income and their employer using this contribution to meet their employer obligation, thereby giving the employer a financial advantage.

Finally, employers are not obliged to disclose their salary sacrifice contribution policies to their employees, meaning these rules may be applied without employees’ knowledge.

Finally, employers are not obliged to disclose their salary sacrifice contribution policies to their employees, meaning these rules may be applied without employees’ knowledge.

Ultimately, salary sacrifice is about giving employees an effective way to boost their retirement savings. The majority of Australians would see it as inherently unfair that an employer can make decisions that have consequences on their decision to save, especially if those decisions were to be made without full and upfront disclosure.

We need a level playing field with employers and members on an equal footing. There also needs to be increased certainty about when and how salary sacrifice operates and there needs to be transparency throughout the process.

It’s not good enough for the Federal Government to trumpet the success of their superannuation reforms when more work is needed.

Andrew Proebstl

Comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum

legalsuper is Australia’s largest industry super fund dedicated to the legal sector, managing close to $1billion. No-commissions apply, and all profits are returned to members. If you would like to obtain a copy of a Guide to Salary Sacrifice please contact David Eastwood at deastwood@legalsuper.com.au

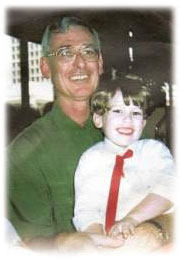

Between the dates of birth and death, of graduation, practice, distinction and retirement, between all the known markers of progression through life runs a current of turbulent energy, the animating force of character. It is in this stream that the real man resides. It is indefinable, unmeasurable, and in anyone worthwhile knowing it is intense, contrary, paradoxical, strongly marked, and mysterious. If this be spirit or soul then let it be. It is unimaginable that it has passed.

It is impossible to fix and hold this energy, but only to describe its qualities, to say how we have experienced it and thus to communicate in an imperfect way what it is. It is the mercury of human character, and if this isn’t true for ordinary men, then it is for Peter McHugh.

It is impossible to fix and hold this energy, but only to describe its qualities, to say how we have experienced it and thus to communicate in an imperfect way what it is. It is the mercury of human character, and if this isn’t true for ordinary men, then it is for Peter McHugh.

He was an unusual man, given to strong opinions, and the possessor of unusual, sometime uncomfortable, qualities. That is why his friends loved him.

He was for example wonderfully, humourously, often unjustly scornful. You don’t see much of that anymore, the ability and the sheer confidence to sweep away any regard for received opinion and the conventional pieties. And after a moment of shock, you realized he was right. It was not, of course, the way to preferment.

At the same time he was deeply sympathetic. No one attracted him more than a battler, or someone who had been injured emotionally or physically. Above all those worn away by time, debility, and events found a champion in McHugh. He always preferred such people as clients, finding them more wholesome and interesting than the powerful or people with money.

And it was only in McHugh that I came to know that, from time to time, the best response to the soiled world is a lofty contempt.

With these go qualities often claimed for others but quietly possessed by McHugh: courage, rectitude, and generosity. He had them in abundance, though as a contrarian he tried hard to conceal them.

He was a man with a talent for friendship, and with the ability to sustain friendship across the decades, even with people with whom he had quarreled. It must be that, simply, he was worth knowing; that his unusual combination of qualities made him vital and interesting. He had the rare ability, unless you displeased him, of making you feel interesting. He didn’t, as so many clever people do, use conversation to project his own personality.

He was a man with a talent for friendship, and with the ability to sustain friendship across the decades, even with people with whom he had quarreled. It must be that, simply, he was worth knowing; that his unusual combination of qualities made him vital and interesting. He had the rare ability, unless you displeased him, of making you feel interesting. He didn’t, as so many clever people do, use conversation to project his own personality.

He is mourned by friends from school who knew him nearly half a century ago; recent friends grieve too.

McHugh knew what mattered. That is why he was known in chambers, and more widely, as The Lord of Lunch.

As if by right Peter would come to be seated in the dominant position at any restaurant table; that is, able to converse both right and left, to get the view, see the room, and summon staff for food and drink. To baffled waitresses he would quote lines from 60’s songs, and to nervous drink waiters he would issue obscure commands like:

“Fire at will”, meaning, thank you, everyone will have a drink.

“Take no prisoners”, which I think meant the same thing.

“Can’t fly on one wing”, which didn’t just mean “have a second drink”. It meant, logically, “Have an even number of drinks” – two, four, six and on.

Then, at the end of lunch (which in the 80’s was often the beginning of dinner) he would with an imperious sweep of the arm gesture to the wreckage of plates and glasses before him, saying “Liberate me”, and reward the young man or woman with a generous “sling”, which he would make sure, by interrogation, went into their pockets, and not to the employer.

Peter, fastidious in everything, was a vegetarian, and his way of telling staff of that fact, particularly in Chinese restaurants was to utter a warning, together with a wave of an index finger. “ No dog”, he would say. We were in Sydney and McHugh had his say at the Ming Dynasty. But the waiter thought it was a question, apologised that they had no dog, but offered that, if we were prepared to wait, they might be able to rustle up a puppy. We didn’t.

I last saw him in life not a week ago, at the head of a table. There was wine, cake, fellowship, and McHugh, conducting.

Peter was very well informed. He had become devoted in youth to ABC Radio National, that well known font of left wing bias and communist propaganda, and that, with a variety of newspapers, kept him up to date with world affairs. He was thus interesting to engage on political questions, on matters of religion, finance and the taxation of barristers; all the things in fact that polite society avoids. He would know, at any given time, details of Middle Eastern policy shifts, the identity of the new French Minister of Culture, the history of Polish border disputes with East Prussia.

It was a real pleasure to be compelled to agree with McHugh on everything. After all he had the facts, he had the sources. And it was all tempered with a sly self-deprecatingness, when he laughed at his own conspiracy theories, and left you defending a position he had led you to, which he had quietly abandoned.

Above all, in his investigation of the behaviour of the world, there was the opportunity to enjoy outrage, which he generously shared. He, and we, could sustain righteous indignation for weeks after some shabby doing he located in the press.

He was a champion of unpopular opinion, and I think in permanent reaction to the brute ill-manneredness of contemporary life, the grasping and the climbing. He was ill suited to advancement, and it was one of his best qualities.

Peter was a very good lawyer. He had an intuitive ability to see a weakness in argument immediately. It was always wise to describe a legal problem to McHugh before going off to court with it, if he had time. Many times I would stand up later that day, my case fortified by McHugh’s attention. Of course I would get the fee, and the future brief. My debt to him is great.

He had no truck with computers or the internet. He didn’t think real scholarship could be done that way. The mainstay of his research was an annotation of the Queensland Statutes called “ The Grey Binder”, that and The Australian Digest. When these publications ceased something went out of McHugh’s practice. I agree with him. These were homely and comfortable things. Electronic law had no attraction for Peter. A simple accumulation of cases he thought no substitute for editorial analysis.

Though a skeptic in many things, and an outright anarchist in others, Peter was scrupulous about the honour and traditions of the profession he had entered. He never misled a colleague or a court, or allowed misunderstanding to stand to his advantage. He was a tough opponent, but courteous and collegiate. He did not suffer fools and he was unforgiving of sharp practice. which is the obligation of us all.

Though he would deny it McHugh was a master of the Australian language. I think in this respect he had the advantage of older parents, whose familiar idiom went back to a more original Australia, with its self reliance, and bush lore.

I learned how to play “cop the crow”, to stick an uninitiated newcomer with an unwanted task, how to “hit the frog and toad” in order to get home, and why, as young Australians now wore baseball caps, there could never be a Third AIF.

He was a museum of old sayings, and the thoughts and attitudes that went with them, which were generally humourous, stoical, and irreverent

McHugh had also accumulated a considerable body of knowledge of the natural world. He could identify all the trees in the shire, and know the quality of their timber, how the tree grew and flowered, and the conditions that it favoured. He kept books to identify birdlife. He had made, as he said, a treaty with the snakes and the other animals at his farm, which both sides honoured.

He consulted almanacs, cyclopedias, guidebooks.

McHugh knew the phases of the moon, and when at his farm you could see by starlight. He kept track of the equinoxes, and the solstices, which had meaning for him, the paths of comets, and the turning star patterns.

His son Robert was born on the summer solstice, and a full moon rose that night. Peter always spoke of some powerful synchronicity at work there, to be sensed only by adepts and by Irishmen.

His son Robert was born on the summer solstice, and a full moon rose that night. Peter always spoke of some powerful synchronicity at work there, to be sensed only by adepts and by Irishmen.

I think he was a Druid. I owe him a way of hearing, and a way of seeing.

Peter has been blessed by his son Robert and by Sue, Robert’s mother, and by his partner Jenny whose love and loyalty has been inspiring, and to whom we have a great obligation.

At a bend in a creek running from state forest, shaded over by subtropical trees, and on a wedge of hillside with high views to the northeast, McHugh ran a small farm. His mangos were glorious and his macadamias, native to the very area, were perfect. He was rightly proud of what the farm produced, and it was plain that its development was spiritually sustaining.

It is hard to think of evening coming in, with the trickle of the creek, and no lantern now flaring or kettle singing.

He was, when minded to be, a great host, and one of life’s great pleasures was to call in on him at the farm when he was there. Soon there would be coffee and cake, fruit, roasted nuts, gin, all taken at his long table above the creek. And then we would be into it, the unsatisfactoriness of the world, the substandardness of human beings, the French.

He was, when minded to be, a great host, and one of life’s great pleasures was to call in on him at the farm when he was there. Soon there would be coffee and cake, fruit, roasted nuts, gin, all taken at his long table above the creek. And then we would be into it, the unsatisfactoriness of the world, the substandardness of human beings, the French.

And all the while the creek would sound, and cool breezes would blow in the trees, and bees would hum, and there was blue sky, and scudding clouds, and against that, which he has now joined, none of what we said mattered.

Richard Galloway

Examination in Chief – Part 2

First, think about the order in which you’ll call your witnesses. Remember that people recall best what they hear first and what they hear last. So you want a strong and effective witness first, and a strong and effective witness last. Bury the losers in the middle.

In a civil case, if you’re acting for a plaintiff and the defendant is vulnerable to a good cross examination (and you are capable of a good cross examination), consider calling the defendant as a hostile witness as your first witness to establish liability. It can be very effective and is definitely not boring. Perhaps call your client last, to wrap up the case and establish the damages.

In a criminal case, the prosecution might save the victim for last – sure to stick in jury’s mind before they retire to deliberate.

While Australian courts do not allow the theatrics Americans some time employ, there are still a few theatrical techniques that can make your presentation stronger. So when you rise to call a witness, consider doing the following, particularly if you’re in front of a jury.

Rise. Just rise. Don’t start speaking until you have risen.

If you can, stand beside, rather than behind, the lectern. It’s a small thing but coming out from behind a lectern will enhance your presentation. If this is possible will depend a bit on how the bar table is structured but even a little bit to one side will help.

Acknowledge the judge, depending on the court and local custom this could be anything from “Thank you, your Honour” if the court indicated it was now your turn, to a more formal “May it please the Court” or perhaps just a nod depending on the circimstances.

Pause. An American trial advocacy teacher, Terry McCarthy, calls this the “LA Law pause”. Any good speaker will pause for just a beat before starting to get the attention of the audience.

If you are trying the case to the court without a jury it’s an effective way to get his or her Honour’s attention away from the cross-word puzzle and on to your witness. Remember this is your case you’re putting on, there is no point in asking questions if the trier of fact’s attention is elsewhere.

Honour primacy – to the extent possible your first question should be something important and substantive. Something to capture the court or jury’s attention right away. Obviously the nature of this will depend on the witness and on the case, but you called this witness for a reason, so get to the point right off.

After a question or two to honour primacy, then you can back-fill. Always use a formal title and surname when addressing the witness. Mr Smith, Mrs Jones, Dr Chang, Professor Burns. Then ask the witness to introduce him or herself. “Mrs Smith, please tell the jury a little about yourself.” Prompt as necessary and as relevant to the case. People generally like to talk about themselves, once they get past the natural nervousness caused by giving evidence.

Many courts permit leading questions on preliminary matters to speed things along. Resist the temptation with a good witness, this is your innings at bat and you need to collect all the runs you can. You want the witness to establish some rapport with the judge or jury, and this is an easy way to do it before you return to substantive matters.

Use transitions. Transitions are a great tool in both direct and cross examination. It smooths the way for both the trier of fact and the witness, and avoids bumbling around. The first transition might be to set the stage for your primacy question:

“Let’s talk about the night of 8 August, in front of the The Old Barrister Hotel, tell the jury what you saw?”

“I saw the defendant bash a young man with stubbie”.

Then you transition to the back-fill, “Mrs Smith, tell us about yourself, for example what do you do for a living?” Then a few more short questions about her and then transition back to the scene of the crime.

“You told us you saw the defendant bash a young man with a stubbie [this is looping, about which more shortly], where were you standing when you saw this?”

Then a few more questions to establish that she had a clear view, the light was good, her eye sight is excellent and then deal with something that is sure to arise on cross. Again, use a transition.

“You told us you were outside the Old Barrister when you saw the bashing, had you previously been inside?”

“How much had you had to drink?”

“Over what period of time?”

“Had the two glasses of wine impaired you in any way?”

Using transitions we’ve hit our key point – she saw the crime, established who she is and where she was, and then diffused a potential area of cross examination, all very smoothly and efficiently.

Generally during examination in chief, after a transition, our questions can be short: who did you see, what were they doing, where did it happen. Particularly with a good, articulate witness, this draws them out and allows them to tell the story in a natural way that enhances credibility. With a poor witness you may have to be far more narrow in your questions to keep the witness on track.

Looping is a technique of emphasis. When anyone listens to anything, whether it is the judge hearing a case or a lawyer sitting through a continuing education lecture, our minds wander. We don’t hear everything. To make sure the trier of fact hears what you think is critical evidence, you can use a technique called looping.

Looping is no more than restating the key point which you got out of the witness, the point you want heard, in the next question. Say the key fact, for whatever reason, is that the plaintiff was driving a blue car, and your witness saw it. The examination might go like this:

[Start with the transition] “Let’s talk about the afternoon of 7 July when you were walking down Edward Street. Did you see the plaintiff?”

“I did”

“And what was she doing?”

“She was driving a car”

“What colour was the car?”

“Blue”

“And which way on Edward Street was the plaintiff driving in the blue car?”

“Toward Alice Street”

“What kind of blue car was it?”

And so on. After a few loops even the most distracted judge or juror will know it was for damn sure a blue car.

Another technique is labelling. The choice of words we use can have a real impact. They did an experiment in the US where they showed a mock jury a film of a car accident, in which two vehicles collided. The experimenters then divided the group and asked one group “At what speed was the red car going before the collison?” and the other group something like “How fast was the red car speeding before the crash”. The second group estimated a speed about 50% higher than the first group because of the way the question was phrased, using labels like speeding and crash instead of neutral words like going or collision.

If done carefully you can also label witnesses. In one case an expert who had received a wildly disproportionate fee for his services, was referred to throughout the trial by the opposition as the $100,000 doctor. This must be done with care and subtlety, but often some branding can be done.

After you ask a question, listen to the witness’s answer. You know what the witness is going to say (at least you had better) and there is a temptation to review your notes or do something else while they give the answer, but if you don’t care why should the judge or jury. Always listen – and look like it’s the most interesting thing you’ve ever heard. That interest will induce the judge or jury to be interested too.

Avoid incantations and lawyer talk. For example banish the phrase “I put it to you” from your vocabulary. Use “before” instead of “prior”. Avoid incantations such as “Did you have occasion to…”, “Did there come a time”, “what, if anything, unusual occurred”. Speak plainly.

Don’t drone. Change your pitch and inflection when asking questions. When we speak in normal conversation we generally have a slight rise in pitch at the end of a question, that should occur in the courtroom as well. Remember evidence in chief is a constant war against boredom, so do everything you can to make it interesting.

There is a story from the US in which during a particularly sonorous examination in chief, a prosecutor noticed that a juror had fallen fast asleep. He looked up at the judge:

“Your Honour, I note juror #7 is asleep, would the court awaken him, please?”

To which the court replied: “You put him to sleep, you wake him up.”

Try to avoid stupid questions. I’m sure you’ve seen some of these on the Internet and thought, oh, they just made that up. But it really happens. I was in a very tragic wrongful death and personal injury case. The husband had been killed and the wife badly injured. She was giving evidence in her case, and her lawyer was establishing how close their relationship had been:

“Now, Mrs Dixon, did you and your husband celebrate your anniversary?”

“Yes, we did.”

“Did you do that once a year?”

In another case a lawyer was asking a mother about her daughter:

“And how long have you known her?”

In planning your questions, remember that you need to appeal to emotions, not intellect, go for the heart not the brain. You want to bring out the facts that illustrate a wrong was done to your client, that justice requires a result in your favor. Use repitition and looping to emphasise the facts that tell that story.

In most every case, even a good witness will have some problem or vulnerability that will be brought out in cross examination. To the extent you know what that is, bring it out yourself during examination in chief. If possible foreshadow it in your opening submissions. That way the sting is taken out and you get to put your spin on it. By the time it comes out in cross, it’s old news and no longer interesting, plus it makes you look honest by showing the judge or jury that you are giving them the whole story, warts and all.

In many cases we have to deal with the stupid or panicked witness. I was at an inquest not too long ago and put forward one of my client’s employees who in our meetings was articulate and had an excellent recall of the events. As soon as he sat in the witness chair his brain went to meltdown. He could barely remember his name. The deer in the headlights stare greeted even the most basic questions.

It was just panic. But very hard to deal with. In these circumstances forget primacy, you need the witness to be coherent before asking anything important. Sometimes spending more time on their background will help, they will adjust to the circumstances. Use some leading questions on preliminary matters, there will usually be no objection and it will sometimes get the witness out of his or her panic if he or she is lead to exactly what you want.

Use a document to refresh recollection. Sometimes just taking a moment to read something will allow their brain cells to reconnect.

Use of a document brings me to the use of exhibits. Generally you will have a bundle or binder, but whatever organizational tool you use, be smooth in the use of documents with a witness. Have each readily at hand in the order you’ll use them. In a jury trial it is excellent practice to have a projector so that the jury can follow along.

If for some reason you have not already supplied them, have a copy ready for the judge, for each opposing counsel and for the witness. If there is a key passage you want the witness to focus on have it highlighted.

Generally showing a document to a witness involves three steps:

1. Ask the judge, “May I show the witness Exhibit A”

2. Show it to opposing counsel if they have not seen it before

3. Hand it to a court officer to hand to the witness

Then, when you go to ask about it, speak plainly: “Do you know what this is?”

Avoid phrases like “do you know what this purports to be” or other such nonsense. Then establish whatever foundation you need and move to the substance.

The idea in handling exhibits is to avoid fumbling around. You want to look like you know what you’re doing, you have a plan, and are a professional. Looking good while examining a witness will give the judge or jury confidence in you and that may transfer to your witness. Recall how uncomfortable it is to watch a play where the actors are uncertain of their lines (your kids’ early dramatic efforts, for example). If you are comfortable, and best of all, not boring, your examination in chief will enhance your case and your chances of success.

Peter Axelrod

Comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum

Introduction

Dealing with electronically stored information (ESI) as potential electronic evidence is a proposition that leaves most Barristers facing the daunting and somewhat unusual feeling of the unknown. Some may even be jaded by past experiences with ‘technology experts’.

Computer forensics is readily defined as the process of identifying, collecting, analysing and presenting ESI for subsequent presentation as electronic evidence before a court of law2. However, the application of computer forensic principles extends beyond the ubiquitous personal computer. For example, forensic examination is critical in examining activity on:

- Data storage devices such as universal serial bus (USB) keys and external hard drives;

- Computer networks and the Internet;

- Communication devices such as mobile phones, personal digital assistants (PDAs) and satellite navigation systems; and

- Consumer electronics such as digital cameras and portable media players with data storage capabilities, including the Apple iPod.

Identification and Collection of Electronic Evidence

Identification and Collection of Electronic Evidence

Computer forensic practitioners are recommended for consultation and/or engagement whenever ESI has the potential to be relied upon as electronic evidence. Even the simple task of turning on a computer may result in substantial alteration or loss of data3. Such incidents also have the potential for an opposing party to put forward a claim of evidence spoliation.

As part of the identification and collection process, a computer forensic practitioner may be engaged to assist in, and appropriately facilitate the execution of a search order,4 to conduct an otherwise court ordered forensic examination,5 or in the preliminary stages of disclosure where electronic documents and/or e-mails are required for review and production.6

From an evidentiary standpoint, failure to engage a computer forensic practitioner with appropriate qualifications, legal knowledge and practical expertise to assist with electronic evidence may lead to:

- Reduction in the weight afforded to, or even worse – inadmissibility of key electronic evidence;7

- Provision of overly technical opinion founded on indecipherable jargon;

- Inability to implement an efficient electronic evidence methodology with regard to time and cost constraints;8

- Inability to efficiently deal with issues of electronic evidence accessibility,9 relevance,10 and privilege;11

- Exceeding jurisdictional and lawful scope — which can easily occur in the collection of electronic evidence from sources on disparate computer networks and the Internet;

- Causing substantial disruption to another party (e.g. a respondent in a search order) which may have adverse implications unless such actions are justified; and

- Compromising the overall integrity of your arguments at pre-trial conference and in the witness box.

The quality of a computer forensic practitioner is measured by their well-rounded ability to provide strategic advisory and opinion, of a hybrid technical and legal nature, which facilitates the timely production of relevant electronic evidence to assist in resolution of the matter.

Data Recovery

As a general principle, with many exceptions, deleted data can still be recovered.12 In addition, data may still be able to be accessed if password-protected, encrypted or when initially and otherwise thought inaccessible. Computer forensics may assist in:

- Recovery of deleted electronic documents and e-mails;

- Recovery of deleted instant messaging (IM) communications; 13

- Recovery of archived e-mails and computers to verify completeness of disclosure;14 and

- Circumventing or ‘cracking’ password-protection and encryption measures.

Questions of Electronic Authenticity

Questions of Electronic Authenticity

Today, over 90% of all business correspondence and documents subsist in an electronic form. The majority of e-mails and electronic documents are tendered as evidence with minimal question as to their authenticity. ESI is essentially data, and data may be copied and appear identical to its source. Consequently, questionable electronic documents, e-mails and even short message service (SMS) messages — in particular, those pertaining to contractual and/or financial agreements, are often put forward, even though forgery can be achieved with relative ease. Computer forensics may assist to:

- Verify the authenticity of,15 and any alterations or modifications to,16 an electronic document or e-mail, even in comparison to a hard-copy printout; and

- Trace the origin of e-mails — where the source is unknown,17 where defamatory,18 or spam (junk) e-mail.19

Reconstruction of Electronic Events

In the majority of cases where reliance is placed upon electronic evidence – computer forensics may also bring everything together to assist in the substantiation or dismissal of an allegation. Such situations may include:

- Responding to an incident where a computer has been used, directly or indirectly, to facilitate impropriety, suspicious or criminal activity;

- Investigating the leakage or theft of confidential information20 or intellectual property (IP);21

- The resolution of an employment dispute – where an employee is alleged to have inappropriately used a computer, the Internet or e-mail.22

Closing Remark

Technology often endeavours to provide greater efficiency in daily life; However, Barristers are spending more time dealing with ESI as part of their practice. Possessing a basic working knowledge of electronic evidence, and its implications, is essential. In addition, the engagement of a competent practitioner to act as a ‘technology translator’ can provide clarity upon your next encounter with electronic evidence.

Seamus E. Byrne1

Seamus welcomes any questions relating to electronic evidence, electronic disclosure/discovery or computer forensics via the Hearsay Forum or e-mail [sbyrne@vincents.com.au].

In the next edition of Hearsay: The (Electronic) Disclosure Revolution — What you need to know regarding the proposed amendments to the Federal Court of Australia and Supreme Court of Queensland practice guidelines relating to electronic disclosure/discovery and litigation.

Comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum

Endnotes

- Lawyer and Director, Forensic Technology with Vincents Chartered Accountants. His website is located at: http://www.seamusbyrne.com.

- Standards Australia, Guidelines for the Management of IT Evidence (HB 171-2003) (2003). Eoghan Casey, Digital Evidence and Computer Crime: Forensic Science, Computers, and the Internet (2nd ed, 2004).

- Egglishaw v ACC [2006] FCA 819 [37]. See also: Egglishaw v ACC [2007] FCA 939.

- Seamus E. Byrne and Geoffrey Lambert, ‘Practice Direction Update: Search (Anton Piller) Orders in Queensland’ (2007) Proctor (Forthcoming).

- For example: Benzlaw and Associates Pty Ltd v Medi-Aid Centre Foundation Ltd & Ors (Order, Supreme Court of Queensland, Chesterman J, 5 June 2007).

- “Disclosure by production requires production of the original documents, electronically if the original was in electronic form or by hard copy if the original was in hard copy form” Shannon & Anor v Park Equipment Pty Ltd [2006] QSC 284, [7] (Atkinson J, 5/10/2006).

- This is prone to occur where an evidence ‘chain of custody’ has not been (or inadequately) documented, or where a practitioner engaged by a party has failed to comply with best practice guidelines pertaining to electronic evidence.

- Sony Music Entertainment (Australia) Ltd v University of Tasmania [2003] FCA 532.

- Questions as to the accessibility of electronic evidence may involve: Balancing the time and cost implications of recovering data from a backup tape based on its apparent probative value: BT (Australasia) Pty Ltd v State of New South Wales & Anor (No 9) [1998] 363 FCA (Sackville J, 9/04/1998). Dealing with legacy (i.e. superseded) computer systems which may contain ‘potentially relevant’ ESI: Davies & Anor v Chicago Boot Company [2006] SASC 241 (Lunn J, 22/06/2006).

- Kennedy v Baker [2004] FCA 562.