Over the duration of the course, however, the reticence to be there subsided and was replaced with the question: “Why can’t we do more of this?”

The advocacy course was intensive. It required the barristers to perform in a mock- court setting. An advocate’s essential skills (an opening, examination-in-chief, cross-examination and closing address) were tested and reviewed.

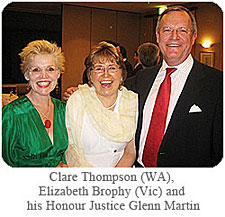

The barristers were coached by experienced counsel (drawn from all the Bars within Australia and the U.K. Bar) and Justice Glenn Martin. The other Queensland coaches were Wensley QC and Boddice SC. The co-ordinator of the course was Phil Greenwood SC from the New South Wales Bar.

The barristers were coached by experienced counsel (drawn from all the Bars within Australia and the U.K. Bar) and Justice Glenn Martin. The other Queensland coaches were Wensley QC and Boddice SC. The co-ordinator of the course was Phil Greenwood SC from the New South Wales Bar.

The barristers participated in groups; each group would perform before a particular coach (coaches were regularly rotated). Each performance was recorded. That performance would then be reviewed by a separate coach viewing the recording. Performance coaches were present to comment on aspects of speech and presentation. Stenographers were also present to transcribe a particular performance; a barrister could then review their performance by examination of the transcript.

Each performance session was preceded by a short talk by a coach on a particular topic. Important things were learnt during these talks including which font styles Martin J prefers in written submissions!

Each performance session was preceded by a short talk by a coach on a particular topic. Important things were learnt during these talks including which font styles Martin J prefers in written submissions!

The most fun part of the course was having dinner together each night. After some imbibing, new discoveries were made such as Wensley QC’s passion for words, literature and Roget’s Thesaurus.

On the final night, dinner was held at the Terrey Hills Golf and Country Club, Terrey Hills. Those present were privileged to hear a short talk given by the Chief Justice of the High Court on the importance of the independence of the bar and the sole practice rule. Transport to and from dinner (in an old school bus) clearly marked the Bar’s move into the 21st century. The highlight of this dinner was the French embrace between Gleeson CJ and Martin J.

Relations between participants was at all times collegial; many friends were made across the various bars of Australia and it felt that we had spent many months together rather than just five days.

Relations between participants was at all times collegial; many friends were made across the various bars of Australia and it felt that we had spent many months together rather than just five days.

The Queensland Bar was represented by: Karen Carmody, Andrew Christie, Kathryn Cochrane, Mark Robertson, Hugh Scott-Mackenzie and myself.

The next course will be run in Sydney from 19-23 January 2009; Brisbane will host the course in 2010. I highly commend the course to anyone interested.

Anand Shah

In its most essential form, accreditation serves to convey to a third party consumer of goods, or services, that the holder of the accreditation has been independently assessed to provide services at a certain level of competency. At the National Mediation Conference held in Darwin in 2004, it was announced that the then Federal Attorney General, the Hon P Ruddock had approved a grant of $30,000 to facilitate a discussion on what were suitable standards for mediation in Australia. The grant was to be administered by the National Mediation Conference Ltd. The Director of the National Mediation Conference (NMC) appointed a sub committee, consisting of Scott Pettersson, Helen Marks and Karen Dey (all then Directors of the NMC) to form the basis of the sub-committee. Their task was to appoint other members to the sub-committee that would be representative of:

⢠the various industry sectors

⢠the geographic diversity of practitioners, and

⢠suitably experienced in both the practice of mediation and also administration of mediation

Professor Laurence Boulle of Bond University was appointed to be the facilitator of the discussions. In Hobart 2006, at the 8th National Mediation Conference in Hobart the Draft National Mediation Accreditation System was approved. The scheme moved to the implementation phase. In Perth in 2008, from 10 to 12 September, the 9th National Mediation Conference will be held. The final approved Australian National Meditator Standard has been released. It is to be found at:

http://www.wadra.law.ecu.edu.au/pdf/Final%20%20Approval%20Standards_200907.pdf

The Standard provides the scope, the qualification and integrity thresholds as well as those for continuing education. It should provide the market for these services with a reasonably objective standard to judge practitioner’s basic ability to act as a mediator at a basic or elementary level. Barrister Mediators will need to assess their position in the light of the new standard. If the Bar Association of Queensland becomes a Registered Mediator Accreditation Body (RMAB), mediators presently listed as mediators with BAQ may, if they conform to the new standard, be accredited in the overall scheme. The new scheme is a totally voluntary scheme, and has been developed on an “opt in” basis for anyone practising mediation in Australia. Doubtless the Association will keep members informed of developments as they occur.

Geoff Gunn

Monday of this week marked the 20th anniversary of your Honour’s appointment as a judge. 20 years before the mast of the District Court. Such are the differences in seniority, that your Honour left the bar barely two years before I joined it and I suspect that the vast majority of barristers here this morning have only ever known your Honour as a Judge. Your Honour’s retirement will bring to an end a judicial career which spanned almost a generation.

The District Courts are a very different institution to that your Honour joined on the 18th of February 1988. If one excludes the Magistrates Court where trials are usually of a far simpler kind, this court is far and away the busiest trial court in the state and as a consequence of the expansion of both its civil and criminal jurisdiction and the increased complexity of trials in both these spheres the life of a District Court Judge has become increasingly demanding and the tasks required of him or her increasingly important to the life of the state. But your Honour has moved with the times and adapted.

Your Honour was a popular and enthusiastic member of the bar who won many friends throughout your career as a prosecutor and a member of the private bar, both in Brisbane and perhaps especially on circuit throughout the state. During this period you contributed to the life of the Bar Association by serving as a member of its important, and often personally demanding complaints sub-committee. On behalf of the Association I thank you for this.

As a Judge your Honour’s reputation was that of a man who was naturally courteous but, stern and even forthright when provoked as can happen in the heat of a process as strenuous as a criminal trial.

But it is not only a person’s professional experience which shapes how they perform as a Judge. Beyond your Honour’s life as a barrister and a Judge the features which seem to have distinguished you have been loyalty and dedication to family and bagpipes. An example of the first of these characteristics is your former relationship with the late Judge Ralph Cormack. This Judge who sat in Townsville was one of nature’s gentlemen who gave your Honour, whose family did not have a background in the law, the great opportunity of working as his Honour’s associate from an early age. Throughout this period your Honour forged a close relationship with the Judge, to whom you remain devoted for the rest of his life. I expect it was a proud day when his Honour was present at your Honour’s swearing in ceremony 20 years ago.

Your Honour is a devoted family man I am told and almost inseparable from your wife of many years. You have three children, Trent, who is a successful solicitor and a member of the firm Minter Ellison. Lisa, an accomplished teacher who has maintained the legal connection of the family by marrying Glen Cranny, a member of Gilshenan & Luton and Trent who is a fine, but somewhat battle-scarred and hardened teacher of the French language. I say this because I know that he endured attempts to impart this beautiful tongue to my two eldest sons and that this was not always plain sailing for him. Your Honour’s children have already provided five glorious grandchildren upon whom you dote with another two in the offing.

This brings me to the pipes. It seems my lot in life to give speeches at ceremonies honouring judicial officers with a strong connection to Scotland and the letter “f”. Your Honour’s love of and mastery of the pipes is known up and down the state. Justice Spender has told me that you have won such a reputation in this field that you are and have for some time now been the custodian of the Spender family pipes upon which you lavish great care.

With these things to sustain you, I suspect your departure from the court simply herald another busy period in your life. The bar wishes your Honour and Mrs Forno a long, happy and fruitful retirement.

May it please the court.

Michael Stewart SC

President

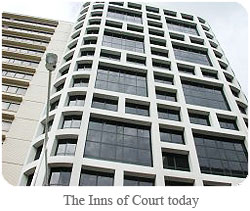

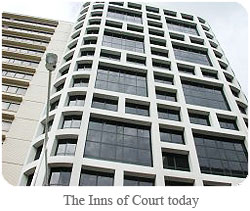

Cedric Hampson Chambers (the official naming function is awaiting completion of renovations) is on Level 17 of the Inns of Court. They are comprised of the following members:

Sally Armitage, Brett Codd, James Crowley QC, Joseph Crowley, Stephen Fynes-Clinton, Geoff Gunn, Peter Lane, Stephen Lumb, Pamela McGhee, John Meredith, Douglas Murphy S.C., Andrew Rich and Ken Watson.

The original group was formed in 1986 when the present Inns of Court opened. The first settlers were: Cedric Hampson QC (ret), Pat Connor (ret), Dan Ryan, Ann Kaye (ret), John McGhee (ret), Douglas Murphy, (now) Federal Magistrate Keith Wilson S.C., Stephen Lumb, Judith Wilson, Tom Somers and Robert Holmes (not ‘Ã Court’; just “caught ”, but that’s another story.)

The original group was formed in 1986 when the present Inns of Court opened. The first settlers were: Cedric Hampson QC (ret), Pat Connor (ret), Dan Ryan, Ann Kaye (ret), John McGhee (ret), Douglas Murphy, (now) Federal Magistrate Keith Wilson S.C., Stephen Lumb, Judith Wilson, Tom Somers and Robert Holmes (not ‘Ã Court’; just “caught ”, but that’s another story.)

Over the last 21 years, others have come and gone, as owners, or tenants, including former state Minister for Survey and Valuation, John Greenwood QC, John Batch QC, Federal Magistrate Michael Jarrett, former Building Tribunal chairman, Barry Cotterell, Richard Morgan, Geoff Diehm, Adrian Duffy and the polo playing, Bill Somerville, to name some. All have learnt well in one way or another.

One of the greatest achievements of these chambers (apart from upholding the Rule of Law) has been the stoic reticence and resilience against renovating the floor. It is the only floor in the Inns that has not been fully renovated since the opening of the building. Although the fake black leather lounges from the Softies bit the dust early in favour of more tasteful furniture, designed by Alice Morris (mother of Violet), the carpet is still the one installed in 1986. In the interests of maintaining some semblance of professional respectability and dignity, it was necessary to cunningly conceal permanent evidence of frivolous functions by strategically placed Persian rugs that have successfully tripped many but which have been loved by Crowley QC since he arrived on the floor in 2005. A beautiful and artistic stained glass divider panel has escaped the stones, glasses and coffee cups of jealous neighbours and the ceiling is beginning to sag in places under the weight of rising hot air. All that will change, however. The new carpet has been woven, paid for and is now in storage awaiting completion of the renovations which will commence sometime in the future. This could be our motto: “RENOVANDUM IN FUTURO”.

Doug Murphy S.C.

Gray’s Inn – Call to Members

The attention of our readers is drawn to the request from the Honourable Michael J Beloff QC of Gray’s Inn, London:

In my capacity as Treasurer of Gray’s Inn for 2008, I am seeking to update our database of our members. If you were called to the Bar by Gray’s Inn I would be grateful if you could email me at michaelbeloff@blackstonechambers.com with your name and date of call. A c.v. with your present professional position would also be welcome.

Yours with every good wishes

The Honourable Michael J Beloff QC

Family Court of Australia Notification

To download a copy of the Family Court of Australia Notification – Consent parenting orders and allegations of abuse – Rule 10.15A, CLICK HERE.

Federal Judicial Appointments Address by The Hon Robert McClelland MP

The Commonwealth Attorney-General, The Hon. Robert McLelland MP outlined his proposed changes to the Federal judicial appointments process at the Bar Association’s annual conference in February 2008. To download a copy of the attorney’s address, CLICK HERE.

CPD 7 – The Art of Effective Persuasion: Performance Skills Workshop – 15 March 2008

Director Elaine Paton of Talking Brief Performance Skills will present CPD 7,The Art of Effective Persuasion: Performance Skills for Advocates Workshop to be held on 15 March 2008 at the Bar Common Room, Inns of Court, Brisbane. For more information, contact Shayne Goodwin at the CPD Office on (07) 3238 5109.

Criminal Bar Meeting – 19 March 2008

Michael Stewart S.C., President of the Bar Association will chair a meeting of the Criminal Bar with the assistance of Davis S.C. and Amerena on 19 March 2008 in the Bar Common Room, Inns of Court, Brisbane at 5.00 pm. The meeting is intended to be a broad forum where members who practice in the criminal jurisdiction are encouraged to air their views. In order to maximise the benefits from the meeting, members are requested to give advance notice of issues they would like to raise. These can be mailed to Davis S.C. at pdavis@qldbar.asn.au or to the Chief Executive at dconnor@qldbar.asn.au

National Pro Bono Survey

The National Pro Bono Centre is conducting a survey of barristers to address the need for reliable data about pro bono legal work in Australia. Endorsed by the Australian Bar Association, the first stage of the survey for solicitors has been completed. A report of this survey for barristers will be published in mid-2008. To complete the barristers online survey, CLICK HERE.

Preparing and Conducting Family Law – Interim Hearings in the Federal Magistrates Court – 3 Part Series – 15 April, 22 May and 14 June 2008

The Queensland Law Society and the Bar Association of Queensland are the presenters of a 3 part series Preparing and Conducting Family Law Interim Hearings in the Federal Magistrates Court. The series will provide practical training for lawyers preparing cases and appearing as advocate within the family law jurisdiction of the Federal Magistrates Court and focus on the essential steps of preparing a case for an interim hearing. For more information, CLICK HERE.

Queensland Law Society Vincents Symposium – 6 March 2008

Queensland Law Society Vincents Symposium – 6 March 2008

The Honourable Chief Justice delivered the opening address at the Queensland Law Society Vincents Symposium held in Brisbane on 6 March 2008. To download a copy of His Honour’s address, CLICK HERE.

UNIFEM International Womens’ Day – 6 March 2008

The Honourable Justice McMurdo AC delivered a speech at the UNIFEM International Women’s Day breakfast held in Brisbane on 6 March 2008. To download a copy of Her Honour’s speech, CLICK HERE.

Legal Aid Queensland CLE Program – Advocacy in the Magistrates Courts – 4 March 2008

Judge Marshall Irwin,Chief Magistrate delivered a speech at Legal Aid Queensland, Advocacy in the Magistrates Courts on 4 March 2008. To download a copy of the address, CLICK HERE.

Facts/Decisions

T he first appellant (Koompahtoo) and the first respondent (Sanpine) entered into a joint venture agreement (“the Agreement”), in July 1997, for the development and sale of a large area of land north of Sydney. Koompahtoo contributed the land and Sanpine was the manager of the project with each party having a 50% interest in the joint venture. In February 2003 the second appellant was appointed as administrator of Koompahtoo. In December 2003 the administrator purported to terminate the Agreement. Sanpine sought, unsuccessfully at first instance, a declaration that the termination was invalid and that the Agreement was still on foot. The primary judge, Campbell J, found that Sanpine had committed significant and repeated breaches of the Agreement in relation to the preparation and updating of documents, the opening and maintenance of a joint venture bank account and the maintenance of proper books so as to allow assessment of the affairs of the joint venture. The primary judge concluded that such breaches were sufficiently serious to give Koompahtoo a right to terminate the Agreement. The New South Wales Court of Appeal (by majority) overturned that decision. Giles JA, with whom Tobias JA agreed, considered that the primary judge had decided the case on the basis that Sanpine had shown a repudiatory intention. Giles JA concluded that the conduct of Sanpine was not such that it evinced an intention to carry out the Agreement only if and when it suited Sanpine to do so. The High Court allowed an appeal from this decision and upheld the decision of the primary judge. Gleeson CJ and Gummow, Heydon and Crennan JJ (“the joint Judges”) found2 that the breaches of the Agreement deprived Koompahtoo of a substantial part of the benefit for which it contracted and that such breaches justified termination. The joint Judges noted that Sanpine was unable to inform the administrator, or even the primary judge, of the true financial position of the joint venture and to produce informative joint venture accounts.3 The joint Judges said4 :

he first appellant (Koompahtoo) and the first respondent (Sanpine) entered into a joint venture agreement (“the Agreement”), in July 1997, for the development and sale of a large area of land north of Sydney. Koompahtoo contributed the land and Sanpine was the manager of the project with each party having a 50% interest in the joint venture. In February 2003 the second appellant was appointed as administrator of Koompahtoo. In December 2003 the administrator purported to terminate the Agreement. Sanpine sought, unsuccessfully at first instance, a declaration that the termination was invalid and that the Agreement was still on foot. The primary judge, Campbell J, found that Sanpine had committed significant and repeated breaches of the Agreement in relation to the preparation and updating of documents, the opening and maintenance of a joint venture bank account and the maintenance of proper books so as to allow assessment of the affairs of the joint venture. The primary judge concluded that such breaches were sufficiently serious to give Koompahtoo a right to terminate the Agreement. The New South Wales Court of Appeal (by majority) overturned that decision. Giles JA, with whom Tobias JA agreed, considered that the primary judge had decided the case on the basis that Sanpine had shown a repudiatory intention. Giles JA concluded that the conduct of Sanpine was not such that it evinced an intention to carry out the Agreement only if and when it suited Sanpine to do so. The High Court allowed an appeal from this decision and upheld the decision of the primary judge. Gleeson CJ and Gummow, Heydon and Crennan JJ (“the joint Judges”) found2 that the breaches of the Agreement deprived Koompahtoo of a substantial part of the benefit for which it contracted and that such breaches justified termination. The joint Judges noted that Sanpine was unable to inform the administrator, or even the primary judge, of the true financial position of the joint venture and to produce informative joint venture accounts.3 The joint Judges said4 :

“It was not within the contemplation of the contract that it should have been necessary for Koompahtoo, at any time, to have engaged in extensive legal process in order to find out what had become of the money borrowed on the security of its land, or to assess the financial state of the joint venture”

Approach of the joint Judges

The following points emerge from the joint judgment:

- The term “repudiation”5 may be used in different senses. First, it may refer to conduct which evinces an unwillingness or an inability to render substantial performance of the contract.6 This may be termed “renunciation” and is sometimes described as conduct which evinces an intention no longer to be bound by the contract or to fulfil it only in a manner substantially inconsistent with the party’s obligations.7 Secondly, repudiation may refer to any breach of contract which justifies termination by the other party, that is, a failure of performance.8

- A failure of performance may entitle the innocent party to terminate a contract in two circumstances. First, where there has been a failure to comply with an “essential” term (sometimes described as a “condition”).9 Secondly, where there has been a sufficiently serious breach of a non-essential term which may be described as an “intermediate” or “innominate” term.10

- With respect to the identification of an “essential” term, the joint Judges endorsed11 the test adopted by Jordan CJ in Tramways Advertising Pty Ltd v Luna Park (NSW) Ltd.12

- With respect to the adoption of the concept of an “intermediate” term, the High Court endorsed13 the doctrine espoused by Diplock LJ in Hongkong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd.14

- In determining the nature of a contractual term, regard should be had to “contractual intention, considered in the light of the language of the contract, the circumstances in which the parties have contracted and their common contemplation as to future performance”.15

- A “sufficiently serious” breach of an intermediate term is one “going into the root of the contract”, a conclusion dependent upon the nature of the contract and the relationship it creates, the nature of the term, the kind and degree of the breach and the consequences of the breach for the other party (and the adequacy of damages as a remedy may be a material factor in deciding whether the breach goes to the root of the contract).16

Alternative approach

Kirby J agreed that the appeal should be allowed. However, his Honour disagreed with the approach of the joint Judges in relation to the endorsement of the concept of “intermediate” terms. Kirby J found that there was no warrant for the adoption of such a concept.17 In cases involving a breach of terms not regarded as essential, Kirby J said that a right to terminate would arise if there were “a breach of a non-essential term causing substantial loss of benefit”.18 His Honour considered that the breaches in the case before the Court had, as a matter of fact, the effect of depriving Koompahtoo of the substantial benefit of the Agreement with the consequence that termination was justified.19

Kirby J agreed that the appeal should be allowed. However, his Honour disagreed with the approach of the joint Judges in relation to the endorsement of the concept of “intermediate” terms. Kirby J found that there was no warrant for the adoption of such a concept.17 In cases involving a breach of terms not regarded as essential, Kirby J said that a right to terminate would arise if there were “a breach of a non-essential term causing substantial loss of benefit”.18 His Honour considered that the breaches in the case before the Court had, as a matter of fact, the effect of depriving Koompahtoo of the substantial benefit of the Agreement with the consequence that termination was justified.19

In rejecting the approach of the joint Judges in relation to “intermediate” terms, Kirby J said:20

“If the classification of a contractual term as ‘intermediate’ is nothing more than a function of ex post facto evaluation of the seriousness of the breach in all of the circumstances then the label itself is meaningless. It is not assigned on the basis of characteristics internal to, or inherent in, a particular term, as the joint reasons themselves acknowledge. Rather, it is imposed retrospectively, in consequence of the application of the judicial process. Effectively, there is no basis, and certainly no clear or predictable basis, for separating ‘intermediate’ terms from the general corpus of ‘non-essential’ terms or ‘warranties’ prior to adjudication in a court. This throws into sharp relief the extreme vagueness of the Hongkong Fir ‘intermediate’ term. Its imprecision occasions difficulties and confusion for parties and those advising them. It has the potential to encourage a proliferation of detailed but disputable evidence in trial courts and consideration of such evidence in intermediate courts. It renders uncertain the distinctions between the several categories said to provide a legal justification for the very significant step of terminating an otherwise valid contract.”

Kirby J also expressed reservations as to whether the reasons of Jordan CJ in Tramways supplied the relevant test for identifying an “essential” term.21

Conclusion

As noted by Kirby J “… the holding in the joint reasons will now endorse the Hongkong Fir doctrine as part of the common law of Australia”.22

The joint Judges did not formulate a test for identifying “intermediate” terms. However, if regard is had to Lord Diplock’s judgment in Hongkong Fir,23 it is apparent that an “intermediate” term is a term which constitutes neither a “warranty” (that is, a contractual undertaking of which it can be predicted that (subject to a stipulation to the contrary) no breach can give rise to an event which will deprive the party not in default of substantially the whole benefit which it was intended that he or she should obtain from the contract)24 nor an essential term25 (that is, a contractual undertaking of which it can be predicted that (subject to a stipulation to the contrary) every breach of such undertaking must give rise to an event which will deprive the party not in default of substantially the whole benefit which it was intended that he or she should obtain from the contract)26. This residual category of term (the intermediate term) is, in the writer’s view, common. Classification of a term depends on contractual intention.27

Notwithstanding Kirby J’s criticism of the approach adopted by the joint Judges in respect of “intermediate” terms, the disparity between the two views may not be as stark as first appears. The joint Judges refer, at [49], to a sufficiently serious breach of a “non-essential term” and they note, at [71], that the relevant breaches of the Agreement “deprived Koompahtoo of a substantial part of the benefit for which it contracted”.28 There is a similarity of language in the competing reasons. In the writer’s view, the only practical distinction between the respective approaches on this issue is that the test adopted by the joint Judges requires the initial identification (or sifting out) of those terms which could be described as warranties.

Kirby J has identified 3 circumstances in which a right to terminate a contract will arise.29 If this tripartite classification is revised to reflect the reasoning of the joint Judges, it is the writer’s view that the conduct of a defaulting party will be sufficient to justify the termination of a contract if:

(a) the defaulting party has breached an essential term (a condition) of the contract (applying the test of essentiality adopted by Jordan CJ in Tramways);

(b) the defaulting party has breached an intermediate term of the contract and such breach goes to the root of the contract (having regard to the nature of the contract and the relationship it creates, the nature of the term, the kind and degree of the breach and the consequences of the breach of the other party (including the adequacy of damages as a remedy)); or

(c) the defaulting party’s conduct amounts to a “renunciation” of the contract (that is, the conduct evinces an intention no longer to be bound by the contract or to fulfil it only in a manner substantially inconsistent with the party’s obligations). This encompasses a “repudiation” of the contract in the traditional sense.

There may be an overlap between the categories in (b) and (c) above, a point identified by the joint Judges. In the writer’s view, such overlap is likely to arise in cases involving multiple breaches (of non-essential terms) of a contract.

Stephen Lumb

- [1962] 2 QB 26 at 69-70.

- At [71].

- At [68].

- At [68].

- The joint Judges deprecated the use of this term to mean “termination” (as had occurred in some cases): see [45].

- At [44].

- At [44].

- At [44].

- At [47].

- At [49].

- At [47]-[48].

- (1938) 38 SR (NSW) 632 at 641-642.

- At [49]-[52].

- [1962] 2 QB 26 at 69-70.

- At [56].

- At [54].

- At [106], [107], [109], [113].

- At [114]

- At [120].

- At [107].

- At [100]-[101].

- At [121].

- [1962] 2 QB 26 at 69-70.

- Hongkong Fir at 70 per Diplock LJ.

- Referred to as a “condition” by Diplock LJ.

- Hongkong Fir at 69-70 per Diplock LJ.

- See paragraph 5 under the heading “Approach of the joint Judges” above.

- Cf Reasons of Kirby J at [121].

- At [114].

- At [44].

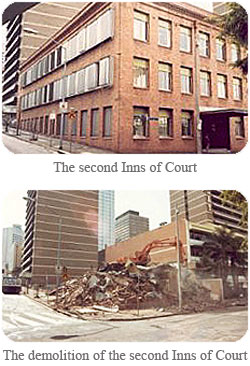

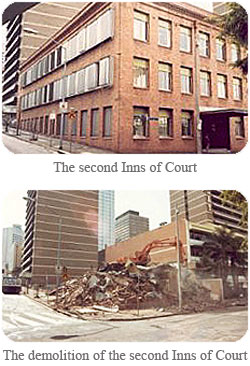

There had been talk for years about redevelopment. Schematic drawings of a new building were floating around. Financing the venture remained the stumbling block. Talks were held with Mr Phil Ridings, the general manager of SGIO. These envisaged a sale of the site to the insurer and a buyback or leaseback of a brand new building. The idea was promising but the impetus was not there.

Cedric Hampson QC was elected chairman of Barristers Chambers Ltd (BCL), in 1972. Redevelopment became an important agenda item. More discussion was had with SGIO but bogged down over the value of the site. A complicating factor was the company shareholding. Not all members of the bar were shareholders of Barristers Chambers Ltd. The purchase price of shares in a redevelopment would be more expensive for them because they would not enjoy a credit for the value of the shares held. Some felt this was unfair. Other members had exaggerated views of the land’s value.

In the early ‘80s’ Barristers Chambers threw its lot in with AV Jennings. That company agreed to build a new Inns. It proposed to build first on the carpark behind the old Inns and when that was finished members would move in, and the old one would be demolished and rebuilt. No movement off the site was involved and so the proposal had general agreement. At the last moment it was discovered that Jennings’s feasibility studies had revealed that it was not possible to build that way. Members would have had to vacate and no arrangements had been made for alternative accommodation. A crisis ensued. Barristers Chambers sacked Jennings and went into the market.

In the early ‘80s’ Barristers Chambers threw its lot in with AV Jennings. That company agreed to build a new Inns. It proposed to build first on the carpark behind the old Inns and when that was finished members would move in, and the old one would be demolished and rebuilt. No movement off the site was involved and so the proposal had general agreement. At the last moment it was discovered that Jennings’s feasibility studies had revealed that it was not possible to build that way. Members would have had to vacate and no arrangements had been made for alternative accommodation. A crisis ensued. Barristers Chambers sacked Jennings and went into the market.

A new company Watpac Pty Ltd which contained elements of the old Watkins family building group was approached. They tendered for the job. The ubiquitous (at that time), Remm Constructions Pty Ltd, also provided a tender. Both employed the buyback formula. Each company showed directors on successive days why it should be selected and Watpac won the “beauty competition”.

Bligh Jessup Brentnell were engaged as architects, planning approval was obtained and working drawings requested. In early 1985 Watpac Pty Ltd was signed up, the building vacated, alternative premises at Brisbane Administration Centre (BAC) and in ASL building in North Quay rented, and building work commenced.

The final arrangements had been achieved through the labours of a building sub-committee (BSC) of Barristers Chambers Ltd, Cedric Hampson QC, Gary Crooke QC, and Glenn Martin. The proposed building, to be economically viable, would have to house at least 150 barristers. The old Inns housed about 50. Shareholders from outside the building were needed. The task of enlisting them was done by members of the sub-committee. They toiled unceasingly to encourage others to take shares.

This is not the time to talk about Cedric Hampson in extenso, but it was only through his verve, his enormous power of persuasion, and his robust determination, that the task was accomplished. Not only that; he more or less designed the building. Catharina Hampson made it a nice double when she persuaded Gary Crooke that her maquette for the foyer should be accepted and she was commissioned to model and then have cast the group that stands in the foyer today.

This is not the time to talk about Cedric Hampson in extenso, but it was only through his verve, his enormous power of persuasion, and his robust determination, that the task was accomplished. Not only that; he more or less designed the building. Catharina Hampson made it a nice double when she persuaded Gary Crooke that her maquette for the foyer should be accepted and she was commissioned to model and then have cast the group that stands in the foyer today.

The Right Honourable Sir Harry Gibbs kindly opened the building on 29 November 1986. That evening members and their guests held a dinner in the common room with about half the party seated in Rumpoles. Closed circuit television linked the two rooms. Lew Wyvill QC proposed the toast to the sub-committee and Glenn Martin responded. Glenn’s was, in my view, the wittiest address ever delivered in the writer’s time at the Bar.*

James Crowley QC

* A DVD of the speeches has been supplied to Hearsay by Cedric Hampson Chambers with a view to providing it online. Unfortunately technical difficulties have conspired to prevent that occurring in time for this edition. Hearsay hopes to provide the speeches in a future edition.

Whilst the test to be applied in respect of apprehended bias may be firmly established in Australia1 as “whether a fair-minded lay observer might reasonably apprehend that the judge might not bring an impartial and unprejudiced mind to the resolution of the question the judge is required to decide”, the actual course that a judge must undertake when such a complaint has been raised is not always clear.

In Australia, in addition to decided cases, obiter, extra-judicial speeches and academic papers, assistance can be derived from the “Guide to Judicial Conduct” that was published by the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration in March 2007.2

The El-Farargy case

The underlying proceedings in El-Farargy v El-Farargy & Ors.3 involved a matrimonial property dispute. Mrs El-Farargy claimed that the matrimonial residence was owned jointly by her husband Mr El-Farargy and herself, whereas Mr El-Farargy countered that a company he controlled with the third respondent, a Sheikh from Saudi Arabia, were the owners.

The proceedings had an extensive history of delay and non-compliance by the husband. During a two day directions hearing the presiding judge made several comments which the third respondent submitted demonstrated an apprehension of bias against him. An application was made by the third respondent for the judge to recuse himself on that basis. The Judge refused the application.

There were two grounds in the application, firstly that the judge had predetermined the issues, and secondly, that certain comments made by the judge at first instance were described by the third respondent (in his grounds of appeal) as “… would cause a fair-minded and informed observer to conclude that there is a real possibility that the learned judge was (whether or not consciously) mocking the third respondent for his status as a Sheikh and/or his Saudi nationality and/or his Arab ethnic origins and/or his Muslim faith.”

In the Court of Appeal, Lord Justice Ward (with whom Lord Justices Mummery and Wilson agreed) commenced his judgment with the foreboding statement: “This is a singularly unsatisfactory, unfortunate and embarrassing matter.” The appeal was allowed on the second ground.

In rejecting the first ground, Lord Justice Ward found:4 “This judge had already had to deal with this matter on many occasions for many days and, in the light of the husband’s appalling forensic behaviour, no observer sitting at the back of his court could have been surprised that he had formed a “prima facie” view nor even that it was “a near conviction”. A fair-minded observer would know, however, that judges are trained to have an open mind and that judges frequently do change their minds during the course of any hearing. The business of this court would not be done if we were to recuse ourselves for entering the court having formed a preliminary view of the prospects of success of the appeal before us. Singer J. did express himself in strong terms and he would have been wiser to have kept his thoughts to himself. But there are times in any trial and in any pre-trial review where a judge is entitled to express a preliminary view and I do not see that Singer J. has over-stepped the mark in the particular circumstances of this case. The husband has behaved disgracefully yet he, noticeably, has not joined in the application for the judge to recuse himself. The Sheikh, who allies himself with the husband, cannot complain too vociferously if some of the judge’s wholly justifiable ire rubs off on him.”

With respect to the second ground however, the Court of Appeal found certain comments of the Judge as being unacceptable. Lord Justice Ward stated:5

“…It will be recalled that Mr Randall [QC for the applicant/third respondent] invited us to read extracts 1-4 with brackets inserted around the offending words. This was an utterly compelling piece of advocacy. There is a world of difference between saying: “If he chose to depart never to be seen again” and gratuitously adding “if he chose to depart on his flying carpet never to be seen again”. Likewise it would have been unexceptional to say that the Sheikh would be present “to see that no stone is unturned”, without glibly adding “every grain of sand is sifted“. The judge could well make the point that he did not know what lines of communication were available to Saudi Arabia or wherever the Sheikh may be yet once again there was no need for the uncalled-for addition of “at this I think relatively fast-free time of the year“. Without the additional words, the judge was making fair points but the incidental injections of sarcasm were quite unwarranted.

The third example is the worst. Mr Cayford [QC for Mrs El-Farargy] quite clearly did not understand why the judge had interrupted his submission that the Sheikh’s case was not entirely clear by commenting that the affidavit was “a bit gelatinous“. He did not understand the interruption because he would not have appreciated that, as Mr Randall correctly submits, the judge was setting himself up to deliver the punch line to his joke, “a bit like Turkish Delight“.

[brackets added]

Not surprisingly a test has been enunciated in the United Kingdom along similar lines to that applied by the High Court in Australia. In a recent House of Lords decision of R v Abroikof6, Lord Bingham of Cornhill observed “the accepted test is that laid down in Porter v Magill [2001] UKHL 67, [2002] 2 AC 357 at para 103: “whether the fair-minded and informed observer, having considered the facts, would conclude that there was a real possibility that the tribunal was biased“.

In the El-Farargy case, the proceedings had been set down for a five week trial to commence in October 2007. After considering the background of the proceedings and its painfully slow progress, Lord Justice Ward stated “I was aghast at the prospect that allowing the appeal would have the effect of putting the hearing back another year….” His Honour then went on to provide an insight as to a number of behind the scenes discussions that took place following the making of the application for recusal: 7

“…Because I was so appalled by this prospect, I spoke to the President [of the Family Division] very shortly before he departed on holiday. I have his permission to disclose what happened. Singer J. was rightly concerned about the application and the effect it would have on the fixture. Very properly he consulted the Head of his Division to discuss the predicament and see whether anything could be done about the listing of the final hearing before another judge of the Division but the emphatic information given by the then Clerk of the Rules was that no other judge could be found to replace him. If he could not hear it, the hearing would have to be vacated and further delay would ensue. I mention this in fairness to the judge because, if the inference could not have been drawn from paragraphs 6 and 7 of his judgment which I have already cited, it surely now can be drawn that he would (and, this is my guess, would willingly) have released the case to another judge of the Division if that could have been arranged. That not being possible, he had to get on with deciding the application and making up his own mind on the merits as he saw them. He was right to make it plain that listing difficulties could have no impact on the outcome.”

[brackets added]

The El-Farargy case is a further example of how an allegation of apparent bias can place a judge in a difficult position of having to rule upon their own conduct. The Judge in that case, not being able to refer the application to a colleague for determination due to a very busy Court, was placed in the unenviable position of having to decide on his own conduct in circumstances when he knew that substantial delay (along with associated cost) to the proceedings was an inevitable result of such an application being granted.

With respect, the background of delay in the proceedings leading up to the El-Farargy case, perhaps encouraged the Judge, borne out of frustration, to make a number of regrettable comments, whilst being cloaked in the veil of humour (excuse the pun).

On a separate issue however, the application for recusal in El-Farargy would most likely have failed in Australia. In El-Farargy the Judge’s decision not to recuse himself, would in Australia, of itself, be found not to be a judgment or order that could properly be the subject of an appeal.8 A recent decision of the NSW Court of Appeal in Jae Kyung Lee v Bob Chae-Sang Char & Ors9 followed the High Court decision in The Queen v Watson; ex parte Armstrong, and rejected an application to disqualify a judge for apprehended bias on that basis. In Australia, the third respondent in El-Farargy could have sought such relief as a ground in his appeal, by raising it as the first ground.10

Judicial Humour

Judicial Humour

Lord Justice Ward, whilst expressing11 his “belief that the injection of a little humour lightens the load of high emotion that so often attends litigation”, continued however “I fully appreciate the conventional view that jokes are a bad thing. Of course they are when they are bad jokes – and I am sure I have myself often erred and committed that heinous judicial sin. Singer J. certainly erred in this case. These, I regret to say, were not just bad jokes: they were thoroughly bad jokes”.

On the topic of courtroom humour, the Chief Justice of Australia, the Honourable AM Gleeson AC12 in an extra-judicial speech, commented on “what might generously be described as judicial humour”:

“Some judges, out of personal good nature, or out of a desire to break the tension that can develop in a courtroom, occasionally feel it appropriate to treat a captive audience to a display of wit. Sometimes this is appreciated by the audience, but sometimes it is not. When it is not the consequences can be very unfortunate. Judges and legal practitioners may underestimate the seriousness which litigants attach to legal proceedings, and they can become insensitive to the misunderstandings which might arise if the judge appears to be taking the occasion lightly or, even worse, if the judge appears to be making fun of someone involved in the case. Without wishing to appear to be a killjoy, I would caution against giving too much scope to your natural humour or high spirits when presiding in a courtroom. Most litigants and witnesses do not find court cases at all funny. In almost ten years of dealing with complaints against judicial officers to the Judicial Commission of New South Wales I have seen many cases where flippant behaviour has caused unintended but deep offence.”

The Guide to Judicial Conduct – Handling an application for recusal

In a “postscript” to his judgment in the El-Farargy case, Lord Justice Ward laments as to the increasing number of applications for recusal arising from apprehended bias and suggests how a Judge might best respond:

“It is an embarrassment to our administration of justice that recusal applications, once almost unheard of, are now so frequently coming to this Court in ways that do none of us any good. It is, however, right that they should. The procedure for doing so is, however, concerning. It is invidious for a judge to sit in judgment on his own conduct in a case like this but in many cases there will be no option but that the trial judge deal with it himself or herself. If circumstances permit it, I would urge that first an informal approach be made to the judge, for example by letter, making the complaint and inviting recusal. Whilst judges must heed the exhortation in Locabail13 not to yield to a tenuous or frivolous objection, one can with honour totally deny the complaint but still pass the case to a colleague. If a judge does not feel able to do so, then it may be preferable, if it is possible to arrange it, to have another judge take the decision, hard though it is to sit in judgment of one’s colleague, for where the appearance of justice is at stake, it is better that justice be done independently by another rather than require the judge to sit in judgment of his own behaviour.”

In Australia steps have been taken to formulate a process in order to assist Judges when responding to an application for recusal. The Guide to Judicial Conduct states at chapter 1.1 that its purpose is, inter alia, to “give practical guidance to members of the Australian judiciary at all levels….Importantly, this publication seeks to be positive and constructive, and to indicate how particular situations might best be handled…”.14

After considering various circumstances when an apprehension of bias may be founded, the Guide to Judicial Conduct refers to the High Court’s comments in Ebner:15

“The application of these principles, and the making of a decision whenever issues of possible bias are raised, call for a good deal of care and common sense. It is useful to bear in mind the remarks of Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ in Ebner at [20]:

This is not to say that it is improper for a judge to decline to sit unless the judge has affirmatively concluded that he or she is disqualified. In a case of real doubt, it will often be prudent for a judge to decide not to sit in order to avoid the inconvenience that could result if an appellate court were to take a different view on the matter of disqualification. However, if the mere making of an insubstantial objection were sufficient to lead a judge to decline to hear or decide a case, the system would soon reach a stage where, for practical purposes, individual parties could influence the composition of the bench. That would be intolerable.”

The Guide to Judicial Conduct then sets out the following procedure for when an application for recusal is made:16

“Disqualification procedure

(a) If a judge considers that disqualification is required, the judge should so decide. Prior consultation with judicial colleagues is permissible and may be helpful in reaching such a decision. The decision should be made at the earliest opportunity.

(b) In cases of uncertainty where the judge is aware of circumstances that may warrant disqualification, the judge should raise the matter at the earliest opportunity with:

(i) The head of the jurisdiction;

(ii) The person in charge of listing;

(iii) The parties or their legal advisers;

not necessarily personally, but using the court’s usual methods of communication.

(c) Disqualification is for the judge to decide in the light of any objection, but trivial objections are to be discouraged.

(d) It will generally be appropriate in cases of uncertainty for the judge to hear submissions on behalf of the parties and that should be done in open court.

(e) The judge should be mindful of circumstances that might not be known to the parties but might require the judge not to sit, and of the possibility of the parties raising relevant matters of which the judge may not be aware. It is not appropriate for a judge to be questioned by parties or their advisers.

(f) If the judge decides to sit, the reasons for that decision should be recorded in open court. So should the disclosure of all relevant circumstances.

(g) Consent of the parties is relevant but not compelling in reaching a decision to sit. The judge should avoid putting the parties in a situation in which it might appear that their consent is sought to cure a ground of disqualification. Even where the parties would consent to the judge sitting, if the judge, on balance, considers that disqualification is the proper course, the judge should so act.

(h) Even if the judge considers no reasonable ground of disqualification exists, it is prudent to disclose any matter that might possibly be the subject of complaint, not to obtain consent to the judge sitting, but to ascertain whether, contrary to the judge’s own view, there is any objection.

(i) The judge has a duty to try cases in the judge’s list, and should recognize that disqualification places a burden on the judge’s colleagues or may occasion delay to the parties if another judge is not available.

There may be cases in which other judges are also disqualified or are not available, and necessity may tilt the balance in favour of sitting even though there may be arguable grounds in favour of disqualification. 3.6 Summary

If these guidelines do not lead the judge to a conclusion, there is a large volume of case law and academic writing that may assist the judge, but in the end the decision to sit or not to sit must rest comfortably with the judicial conscience.”

Conclusion

Whilst there is, as in the El-Farargy case, some degree of judicial lament at the increasing occurrence of allegations of apparent judicial bias, there is no doubt that the preparedness to entertain such applications (at least those with some merit) clearly exemplifies judicial impartiality to the community.

In a further extra-judicial speech, Chief Justice Gleeson considered the positive aspects of a society in which individuals have an ever increasing awareness of their rights17:

“Modern lawyers, litigants, and witnesses, and the public generally, are much more ready to criticise judges whose behaviour departs from appropriate standards of civility and judicial detachment. This is a good thing. If judges behave inappropriately, they should be criticised. Of course, on occasions, some judges are exposed to wrongheaded, extravagant, or unfair criticism. That is the price that has to be paid to remind all judges of the necessity to conduct themselves with dignity and decorum.”

In a paper entitled “Judicial Qualities and Corruptive Good Customs”, published in “Justice According to the Law: A Festschrift for the Honourable Mr Justice BH McPherson CBE”18, Justice Dowsett of the Federal Court of Australia wrote:

“Some litigants-in-person have realized the benefit of the strategic allegation of apparent bias when they want adjournments or to escape sticky situations. Very often, a judge who attempts to identify any valid point in a mass of patently unarguable points will afford ammunition for such an allegation. The problem is not limited to self-represented litigants. Some practitioners have not been as careful as they should have been. On occasions it has been difficult to avoid the conclusion that they have mounted allegations of perceived bias for tactical reasons, or at least have not been sufficiently industrious in seeking to dissuade their clients from instructing them to do so. Justified and unjustified allegations of perceived bias cause great damage. Public confidence is a fickle thing.”

As Justice Dowsett suggests, there is an obligation upon practitioners to properly advise their clients so as not to bring applications that are frivolous or based on ulterior motives. Circumstances may dictate the most appropriate course, however precedent, obiter dictum, extra-judicial and academic papers and publications such as the Guide to Judicial Conduct will provide learned guidance to all parties involved when attempting to work through the maze of conflicting issues that often attends such an application.

I respectfully suggest that practitioners will be assisted by having regard to the Guide to Judicial Conduct should they find themselves having to consider making an application for recusal of a Judge for an apprehension of bias, or any other issue involving impartiality. This in turn will assist the Court through what are often difficult circumstances.

John Meredith

Footnotes

- Johnson v Johnson (2000) 201 CLR 488 at 492 [11], per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ. and Ebner v Official Trustee in Bankruptcy (2000) 205 CLR 337 at 344-345 [6]-[8], in the joint reasons of Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ.

- Second edition. The Guide was published for The Council of Chief Justices of Australia by the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration Incorporated.

- [2007] EWCA 1149 (15 November 2007) (“the El-Farargy case”).

- At [26]

- At [28] — [29]

- [2007] UKHL 37 (17 October 2007)

- At [19]

- The Queen v Watson; ex parte Armstrong [1976] HCA 39; (1976) 136 CLR 248, Barton v Walker [1979] 2 NSWLR 740. Relief pursuant to s.43 of the Judicial Review Act 1991 (Qld) is not available as the decision is obviously not of an “administrative character“.

- [2008] NSWCA 13 (26 February 2008)

- Antoun v The Queen (2006) 80 ALJR 487 at 499[2] per Gleeson CJ and Concrete Pty Ltd v Parramatta Design and Developments Pty Ltd & Anor. [2006] HCA 55; (2006) 231 ALR 663; (2006) 81 ALJR 352 (6 December 2006).

- At [30]

- “The Role of the Judge and Becoming a Judge”, delivered at the National Judicial Orientation Programme, Sydney, 16 August 1998, http://www.hcourt.gov.au/speeches/cj/cj_njop.htm

- Locabail (UK) Ltd v Bayfield Properties [1999] EWCA Civ 3004.

- The web address for the Guide is: http://www.aija.org.au/online/GuidetoJudicialConduct(2ndEd).pdf . I have been unable to locate any equivalent type of guideline for use by Judges in England and Wales.

- At page 11.

- In paragraphs 3.5 and 3.6, at pages 15-16.

- “The Role of the Judge and Becoming a Judge”, a speech delivered at the National Judicial Orientation Programme, Sydney, 16 August 1998.

- Supreme Court Library, 2006, page 368, at page 380.

There had been significant removal of front line Roman legions before this date either in the support of attempts by self-proclaimed emperors to seize the western emperorship (such as Magnus Maximus in 383AD) or to defend Rome itself (Stilicho in 396AD). After these events, whatever Roman army remained (that is professional front-line soldiers) was substantially used to support another self-proclaimed emperor (Constantine III) in 407AD.

The traditional military supply economy that sustained the wealth of Roman Britain no longer operated. Institutions such as the courts which had operated under the authority of the emperor either ceased to function at all or would have had serious limitations on their authority. After all, whose laws were being enforced and by whose authority were those decisions enforced?

The traditional military supply economy that sustained the wealth of Roman Britain no longer operated. Institutions such as the courts which had operated under the authority of the emperor either ceased to function at all or would have had serious limitations on their authority. After all, whose laws were being enforced and by whose authority were those decisions enforced?

A view has been put forward that at this time Roman Britain, or parts of it, underwent a peasant revolt.1 This view draws support from the bagaudae revolts which took place at this time in Gaul (modern day France). Certainly the archaeological evidence attests to an almost complete cessation of Roman style building at this time and the turning over of farms from surplus generating agriculture to subsistence agriculture.2

The traditional school of thought is that the defenceless Britons were now ripe for subjugation and extermination at the hands of invading Angles, Saxons and Jutes who pushed the hapless Britons westward to what is now modern day Wales.3 Sir Victor Windeyer, the distinguished High Court of Australia Judge and legal historian, accepted this view and described the Britons as “effete”.4 It is both misleading and inaccurate and is redolent of history being the propaganda of the victor. Not only were there British kingdoms established in this post-Roman period such as Rheged, Elmet and Dumnonia, but also a British force won a resounding victory against a Saxon force at Mons Badonicus in around 500AD. This victory is written about by the British cleric Gildas in his work De Excidio Britonum, referred to later in this article. Gildas praises the British leader of the period who had an obvious Roman name, Ambrosius Aurelanius.5

However, what is indisputable is that Anglo-Saxon culture over time subsumed both the laws and language of the native Britons in those kingdoms that became Anglo-Saxon and who in many instances became literally second-class citizens under Anglo-Saxon law.

Anglo-Saxon law

The Venerable Bede records that the first written codification of English law took place under the reign of King Aethelbert in the Kingdom of Kent in around 600AD. Aethelbert had been a pagan king who had been converted to Christianity and Bede records that the first of his laws (known as “Dooms”) dealt with the Christian Church.6 Dooms were in fact regal proclamations prescribing what the law was where customary law was either ambiguous or non-existent.

Anglo-Saxon law

The Venerable Bede records that the first written codification of English law took place under the reign of King Aethelbert in the Kingdom of Kent in around 600AD. Aethelbert had been a pagan king who had been converted to Christianity and Bede records that the first of his laws (known as “Dooms”) dealt with the Christian Church.6 Dooms were in fact regal proclamations prescribing what the law was where customary law was either ambiguous or non-existent.

There were no professional judges to adjudicate on disputes either criminal or civil at this time. Such judges did not occur in England until after the Norman Conquest. The usual institution utilised for satisfying disputes was the “hundred”. Originally a military term it became the term used to denote the free male population of a collection of villages or townships. When it met it was known as the “hundred moot”. It gathered monthly and had administrative as well as judicial functions. There were also shire or county moots but having regard to distances and geography these met about twice a year and so the hundred moot was more likely to be the usual venue for dispute resolution. It performed a function not dissimilar to a modern day jury in that lay people decided the outcome of the dispute.

The usual method of trial was by compurgation. This meant the disputant and supporting persons giving an oath attesting to the truth of the disputant’s case. The statement of the witness dealt not only with the facts but, in effect, was an affirmation of the truth of the whole of the claim or the defence of it. The oath had to be given according to a strict formula and if this was not followed the oath was disallowed. The number of oaths needed by a disputant varied according to the nature of the dispute and also the status of the person giving the oath. An eorlman’s (a nobleman) oath was worth 6 times that of a person from the clierlisc (commoner) class. If for some reason a disputant could not give an oath then trial by ordeal was resorted to. This usually involved the inflicting of some trauma either by water or fire which, in keeping with pagan superstitions, were believed to be inhabited by deities and could thus render a supernatural verdict.

Welsh law

Gildas says in his De Excidio Britonum (The Ruin of Britain) that:-

Welsh law

Gildas says in his De Excidio Britonum (The Ruin of Britain) that:-

“Britain has Kings, but they are tyrants; she has judges but unrighteous ones …”

It would appear that the idea of a professional judge to decide cases was entrenched in the communities of the Cymri. No doubt this was inherited from Roman institutions and survived in Northern Wales insofar as the settling of civil disputes was concerned well into the 16th Century. There were also professional lawyers,7 called cynghaws (pleader) or canllaw (guide). The cynghaws were advocates who argued cases in the courts.

The first written Welsh laws were attributed to Hywel Dda (a tenth century Welsh King) and appear to deal with a wider range of topics than the Anglo-Saxon dooms. Like the hundred moots, the trial of a dispute was by compurgation but the witnesses dealt with the facts not the law.

One fascinating aspect of early Welsh property law was the specific prescription of who owned the family cooking pot, the cauldron.8 The cauldron always went to a male on either divorce or death. That there were special laws dealing with this otherwise humble home item reflects the Celtic reverence for cauldrons unaffected by the four centuries of Roman occupation. Cauldrons have been found in numerous lakes and bogs in both Britain and Europe and were obviously placed there as votive offerings. Cauldrons also feature prominently in early Welsh legendary tales of King Arthur including Cyfranc Culhwch a Olwen and Preiddiau Annwfn. In the former, Arthur is set a number of tasks including going to Ireland to retrieve a magic cauldron and in the latter he leads a raid into the magical land of Annwn to steal its treasures including a cauldron.

Anglo-Saxon hegemony

Over the ensuing centuries many of the independent British kingdoms were absorbed by Anglo-Saxon ones until Britain became divided into those east of Offa’s Dyke (Anglo-Saxon) and those west (Welsh). The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms gradually modified the laws and customs derived from barbaric and pagan practices principally because of the influence of Christianity. The falling into desuetude of trial by ordeal being a notable example of this influence.

Surviving Welsh kingdoms became stronger, the notable ones being Powys and Gwenydd which retained those legal institutions modelled on Roman ones.

However, separation by language and antipathy ensured that neither legal system influenced the other.

Ken Watson

Footnotes

- The Decline and Fall of Roman Britain by Neil Faulkner, Tempus, 2004, pages 256-257.

- Britain AD by Francis Pryor, Harper Perennial, 2004, page 196.

- The word “Wales” is derived from the Old English word “wealh” which, ironically, means foreigner. The Britons called themselves “combrogi” from which is derived the Welsh name for Wales which is Cymru.

- Lectures on Legal History by Sir Victor Windeyer, Law Book Co, 2nd Revised Edition, page 2.

- The “invasion” theory no longer commands universal acceptance and has been challenged on archaeological grounds by such notable archaeologists as Francis Pryor. See his work Britain AD, op.cit, chapter 6.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Penguin Books, 1990 revised edition, pages 111-112.

- The Legal History of Wales by Thomas Glyn Watkin, University of Wales Press, 2007, at page 72.

- Watkin, op.cit, page 5.

Insurance for Barristers Chambers available through SFC

The barristers were coached by experienced counsel (drawn from all the Bars within Australia and the U.K. Bar) and Justice Glenn Martin. The other Queensland coaches were Wensley QC and Boddice SC. The co-ordinator of the course was Phil Greenwood SC from the New South Wales Bar.

The barristers were coached by experienced counsel (drawn from all the Bars within Australia and the U.K. Bar) and Justice Glenn Martin. The other Queensland coaches were Wensley QC and Boddice SC. The co-ordinator of the course was Phil Greenwood SC from the New South Wales Bar. Each performance session was preceded by a short talk by a coach on a particular topic. Important things were learnt during these talks including which font styles Martin J prefers in written submissions!

Each performance session was preceded by a short talk by a coach on a particular topic. Important things were learnt during these talks including which font styles Martin J prefers in written submissions! Relations between participants was at all times collegial; many friends were made across the various bars of Australia and it felt that we had spent many months together rather than just five days.

Relations between participants was at all times collegial; many friends were made across the various bars of Australia and it felt that we had spent many months together rather than just five days.

The original group was formed in 1986 when the present Inns of Court opened. The first settlers were: Cedric Hampson QC (ret), Pat Connor (ret), Dan Ryan, Ann Kaye (ret), John McGhee (ret), Douglas Murphy, (now) Federal Magistrate Keith Wilson S.C., Stephen Lumb, Judith Wilson, Tom Somers and Robert Holmes (not ‘Ã Court’; just “caught ”, but that’s another story.)

The original group was formed in 1986 when the present Inns of Court opened. The first settlers were: Cedric Hampson QC (ret), Pat Connor (ret), Dan Ryan, Ann Kaye (ret), John McGhee (ret), Douglas Murphy, (now) Federal Magistrate Keith Wilson S.C., Stephen Lumb, Judith Wilson, Tom Somers and Robert Holmes (not ‘Ã Court’; just “caught ”, but that’s another story.) Queensland Law Society Vincents Symposium – 6 March 2008

Queensland Law Society Vincents Symposium – 6 March 2008 he first appellant (Koompahtoo) and the first respondent (Sanpine) entered into a joint venture agreement (“the Agreement”), in July 1997, for the development and sale of a large area of land north of Sydney. Koompahtoo contributed the land and Sanpine was the manager of the project with each party having a 50% interest in the joint venture. In February 2003 the second appellant was appointed as administrator of Koompahtoo. In December 2003 the administrator purported to terminate the Agreement. Sanpine sought, unsuccessfully at first instance, a declaration that the termination was invalid and that the Agreement was still on foot. The primary judge, Campbell J, found that Sanpine had committed significant and repeated breaches of the Agreement in relation to the preparation and updating of documents, the opening and maintenance of a joint venture bank account and the maintenance of proper books so as to allow assessment of the affairs of the joint venture. The primary judge concluded that such breaches were sufficiently serious to give Koompahtoo a right to terminate the Agreement. The New South Wales Court of Appeal (by majority) overturned that decision. Giles JA, with whom Tobias JA agreed, considered that the primary judge had decided the case on the basis that Sanpine had shown a repudiatory intention. Giles JA concluded that the conduct of Sanpine was not such that it evinced an intention to carry out the Agreement only if and when it suited Sanpine to do so. The High Court allowed an appeal from this decision and upheld the decision of the primary judge. Gleeson CJ and Gummow, Heydon and Crennan JJ (“the joint Judges”) found2 that the breaches of the Agreement deprived Koompahtoo of a substantial part of the benefit for which it contracted and that such breaches justified termination. The joint Judges noted that Sanpine was unable to inform the administrator, or even the primary judge, of the true financial position of the joint venture and to produce informative joint venture accounts.3 The joint Judges said4 :

he first appellant (Koompahtoo) and the first respondent (Sanpine) entered into a joint venture agreement (“the Agreement”), in July 1997, for the development and sale of a large area of land north of Sydney. Koompahtoo contributed the land and Sanpine was the manager of the project with each party having a 50% interest in the joint venture. In February 2003 the second appellant was appointed as administrator of Koompahtoo. In December 2003 the administrator purported to terminate the Agreement. Sanpine sought, unsuccessfully at first instance, a declaration that the termination was invalid and that the Agreement was still on foot. The primary judge, Campbell J, found that Sanpine had committed significant and repeated breaches of the Agreement in relation to the preparation and updating of documents, the opening and maintenance of a joint venture bank account and the maintenance of proper books so as to allow assessment of the affairs of the joint venture. The primary judge concluded that such breaches were sufficiently serious to give Koompahtoo a right to terminate the Agreement. The New South Wales Court of Appeal (by majority) overturned that decision. Giles JA, with whom Tobias JA agreed, considered that the primary judge had decided the case on the basis that Sanpine had shown a repudiatory intention. Giles JA concluded that the conduct of Sanpine was not such that it evinced an intention to carry out the Agreement only if and when it suited Sanpine to do so. The High Court allowed an appeal from this decision and upheld the decision of the primary judge. Gleeson CJ and Gummow, Heydon and Crennan JJ (“the joint Judges”) found2 that the breaches of the Agreement deprived Koompahtoo of a substantial part of the benefit for which it contracted and that such breaches justified termination. The joint Judges noted that Sanpine was unable to inform the administrator, or even the primary judge, of the true financial position of the joint venture and to produce informative joint venture accounts.3 The joint Judges said4 : Kirby J agreed that the appeal should be allowed. However, his Honour disagreed with the approach of the joint Judges in relation to the endorsement of the concept of “intermediate” terms. Kirby J found that there was no warrant for the adoption of such a concept.17 In cases involving a breach of terms not regarded as essential, Kirby J said that a right to terminate would arise if there were “a breach of a non-essential term causing substantial loss of benefit”.18 His Honour considered that the breaches in the case before the Court had, as a matter of fact, the effect of depriving Koompahtoo of the substantial benefit of the Agreement with the consequence that termination was justified.19

Kirby J agreed that the appeal should be allowed. However, his Honour disagreed with the approach of the joint Judges in relation to the endorsement of the concept of “intermediate” terms. Kirby J found that there was no warrant for the adoption of such a concept.17 In cases involving a breach of terms not regarded as essential, Kirby J said that a right to terminate would arise if there were “a breach of a non-essential term causing substantial loss of benefit”.18 His Honour considered that the breaches in the case before the Court had, as a matter of fact, the effect of depriving Koompahtoo of the substantial benefit of the Agreement with the consequence that termination was justified.19  In the early ‘80s’ Barristers Chambers threw its lot in with AV Jennings. That company agreed to build a new Inns. It proposed to build first on the carpark behind the old Inns and when that was finished members would move in, and the old one would be demolished and rebuilt. No movement off the site was involved and so the proposal had general agreement. At the last moment it was discovered that Jennings’s feasibility studies had revealed that it was not possible to build that way. Members would have had to vacate and no arrangements had been made for alternative accommodation. A crisis ensued. Barristers Chambers sacked Jennings and went into the market.

In the early ‘80s’ Barristers Chambers threw its lot in with AV Jennings. That company agreed to build a new Inns. It proposed to build first on the carpark behind the old Inns and when that was finished members would move in, and the old one would be demolished and rebuilt. No movement off the site was involved and so the proposal had general agreement. At the last moment it was discovered that Jennings’s feasibility studies had revealed that it was not possible to build that way. Members would have had to vacate and no arrangements had been made for alternative accommodation. A crisis ensued. Barristers Chambers sacked Jennings and went into the market. This is not the time to talk about Cedric Hampson in extenso, but it was only through his verve, his enormous power of persuasion, and his robust determination, that the task was accomplished. Not only that; he more or less designed the building. Catharina Hampson made it a nice double when she persuaded Gary Crooke that her maquette for the foyer should be accepted and she was commissioned to model and then have cast the group that stands in the foyer today.

This is not the time to talk about Cedric Hampson in extenso, but it was only through his verve, his enormous power of persuasion, and his robust determination, that the task was accomplished. Not only that; he more or less designed the building. Catharina Hampson made it a nice double when she persuaded Gary Crooke that her maquette for the foyer should be accepted and she was commissioned to model and then have cast the group that stands in the foyer today. Judicial Humour

Judicial Humour The traditional military supply economy that sustained the wealth of Roman Britain no longer operated. Institutions such as the courts which had operated under the authority of the emperor either ceased to function at all or would have had serious limitations on their authority. After all, whose laws were being enforced and by whose authority were those decisions enforced?

The traditional military supply economy that sustained the wealth of Roman Britain no longer operated. Institutions such as the courts which had operated under the authority of the emperor either ceased to function at all or would have had serious limitations on their authority. After all, whose laws were being enforced and by whose authority were those decisions enforced? Anglo-Saxon law

The Venerable Bede records that the first written codification of English law took place under the reign of King Aethelbert in the Kingdom of Kent in around 600AD. Aethelbert had been a pagan king who had been converted to Christianity and Bede records that the first of his laws (known as “Dooms”) dealt with the Christian Church.6 Dooms were in fact regal proclamations prescribing what the law was where customary law was either ambiguous or non-existent.

Anglo-Saxon law

The Venerable Bede records that the first written codification of English law took place under the reign of King Aethelbert in the Kingdom of Kent in around 600AD. Aethelbert had been a pagan king who had been converted to Christianity and Bede records that the first of his laws (known as “Dooms”) dealt with the Christian Church.6 Dooms were in fact regal proclamations prescribing what the law was where customary law was either ambiguous or non-existent. Welsh law

Gildas says in his De Excidio Britonum (The Ruin of Britain) that:-

Welsh law

Gildas says in his De Excidio Britonum (The Ruin of Britain) that:-