Submissions for the consultation being conducted by a Committee headed by Father Frank Brennan SJ closed on 15 June 2009. Expatriate lawyer, human rights activist over four decades and general celebrity, Geoffrey Robertson QC, has let loose on Australian readers a brilliant “little book” carrying as a title, the outrageously punned The Statute of Liberty.

In an early chapter, Mr. Robertson attempts to chronicle the development of human rights thinking through history. As AC Grayling and Lynn Hunt, both reviewed in these pages, have shown, a complete chronicling of the struggles for human rights can never be achieved for there has been no end to the struggles. Mr. Robertson’s comparatively shorter attempt starts with the Magna Carta in 1215. The Petition of Right, drafted by Edward Coke, a judge sacked by Charles I for daring to think that he could make independent decisions, ranks an honourable mention.

This starts a curious interplay between Parliament and the Courts in which one and then the other takes the lead in protecting rights. The Parliament of 1640, after a long absence at the behest of the same Charles I, established the principle of an independent judiciary by passing a law that judges did not serve at the pleasure of the king but could not be dismissed except for proven misbehaviour. A year later, the same Parliament abolished the Star Chamber so that torture, henceforth, was abhorrent to English law.2 In 1670, in contrast, it was appeal courts, through a grant of habeas corpus, defending the right of a jury to acquit, despite the strictures of the trial judge who locked them up without food, water or even toilet facilities of any kind. Later, it was an activist judge, Richard Pratt, who established that “an Englishman’s home is his castle” against government ministers, acting at the behest of an outraged King George III, who issued “general warrants” that the home and printery of a critic of the Mad King, John Wilkes, be raided and that the police seize everything on which they could lay their hands.

Mr. Robertson’s survey of history goes on through more British history; the French and American declarations of rights and the horrific events in Europe during the Second World War that led, eventually, with distinguished involvement of Australian politicians and diplomats, to the Universal Declaration of just over 60 years ago. In the few events I have quoted, however, one may see that democracy and the rights that are associated with a functioning democracy do not involve a simple duality of virtuous politicians and bad, power hungry judges. Rather, it was Parliament that saw the virtue of an independent judiciary. That judiciary has, along with many other actors, played a role in rights protection since that time.

Mr. Robertson does not ignore Australian history. He looks at failures of Australian legal processes to make a clear statement for universal rights protection, starting with the pro-male and anti-Catholic nature of the Act of Settlement of 1701 which underpins the rules by which members of the British/Australian royal family may proceed to the Crown. The deficiencies extend further, however, to a failure to entrench the right to vote; the absence of any effective right to trial by jury; the race power which remains a power to discriminate on the grounds of race;3 and the absence, in the wake of the Al-Kateb decision,4 of any protection against indefinite detention without cause.

Perhaps, one of the most important contributions by The Statute to the current debate is its emphasis on positive aspects of Australian history and the desire (and suggested means) of honouring these high points in a preamble to a human rights act. Mr. Robertson commences by describing the forgotten (unknown, at least to this reviewer) historical fact that Governor Arthur Phillip not only protected the convicts in his first fleet by ensuring their correct provisioning with food and water but also declared, as the first law of the new settlement, that there would be no slavery in a free land and that there would be no slaves.

The preamble seeks, inter alia, to acknowledge dispossession of the first owners of the continent and record last year’s apology; acknowledge the common law legacies of the Magna Carta, trial by jury (which saved the lives of many of the convict settlers so they could be transported) and the abhorrence of torture; the sacrifice of Australian soldiers to preserve basic rights for Australians and others; Australia’s fine history in preserving labour rights; and Australia’s contribution to the Universal Declaration and the protection of rights through international law. It is a pity that more debate has not occurred on the shape of an Australian human rights act but Mr. Robertson has, with his preamble, and the body of his suggested act, made a significant contribution.

Much of the second half of The Statute is devoted to discussing experiences with Rights Charters in other countries and, in more recent years, in the ACT and Victoria. In doing this, Mr. Robertson demolishes many of the half truths; misstatements; and urban myths that get recounted ad nauseum by opponents of a human rights act. This reviewer has dealt at some length with Mr. Robertson’s rebuttal of many of the claims by opponents in another forum. I do not propose to recount them here.

I do wish to conclude, however, by reminding my readers of the authority based on experience with which Mr. Robertson offers his views. Certainly, the present reviewer, along, I suspect, with many of the opponents of the concept of an Australian human rights act, comes to the debate with a very different experience profile:

“I have spent my professional life making arguments based on bills of rights. Some have saved the lives of prisoners on death row, others have achieved release for dissidents wrongly detained by arrogant governments, or beaten up by over-powerful police. Many of my clients have been journalists, and arguments based on free-speech guarantees have won them in Europe the right to protect their sources, to lift suppression orders and to publish responsible stories on matters of public importance without being successfully sued for defamation. I have invoked human rights on behalf of the Indian farmer in Fiji denied a right to democracy; on behalf of refugees in Hong Kong denied the right to join their families; on behalf of Catholics wrongfully detained in Singapore; and for victims of Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, Malawi’s Hastings Banda and Chile’s general Pinochet. I have used them of behalf of decent, law abiding people who have been treated unfairly by government officials … in none of these cases have unelected judges seized power from elected representatives — the Fiji case restored democracy (all too briefly), and the others came to court because elected representatives declined to act, or were content that these issues been decided by judges equipped by training and learning to make better decisions than parliament.”

It is the reasoned arguments and the judicious presentation of data that, primarily, makes The Statute of Liberty such a valuable contribution to the debate whether Australia should have a human rights act. The curriculum vitae of the author, however, adds a significant degree of “street cred” to the mix, as well.

Price wise,5 The Statute of Liberty is a steal. I suspect that the time you spend reading the modest 223 pages will be an even better investment than the purchase price.

Stephen Keim SC

Footnotes

- Vintage is an imprint of the UK publisher, the Random House Group which is, in turn, owned by the media company, Bertelsmann AG. Geoffrey Robertson’s author page at Vintage is here. For details of the publisher, go to this site.

- A principle, along with open justice, restated recently in the Binyam Mohamed litigation. See Binyam Mohamed v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2008] EWHC 2048 and [2009] EWHC 152.

- See Kartinyeri v The Commonwealth [1998] HCA 22; 195 CLR 337.

- Al-Kateb v Godwin [2004] HCA 37; 219 CLR 562.

- The recommended retail price is $19.95, miniscule in this day and age.

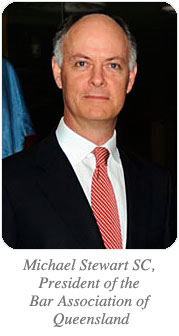

In the last edition of Hearsay we published this image of two toddlers – and then asked whether anyone could identify them with the aid of a clue – both are Silks.

In what was perhaps the most enthusiastic response received by Hearsay to a published article to date, quite a number of members responded.

Although Hearsay is pleased to record that the responses were so numerous that we may now confidently assert that the readership has climbed to double figures, unfortunately none were correct.

Most responses suggested Liam and Declan Kelly or David and Tim North.

However the corerct answer is:

Scroll down …

Michael Stewart SC

and

David North SC

II WHAT IS EXTRA-CURIAL PUNISHMENT?

Extra-curial (or extra-judicial) punishment might broadly be described as serious loss or detriment suffered by an offender as a result of having committed an offence.

The loss or detriment might be attributed to some misadventure experienced during or after the offence. For example, where, during a robbery, an offender accidentally shoots himself causing serious injury.1 Or, where a methylamphetamine manufacturer suffers serious burns when chemicals used in the manufacture explode.2

Alternatively, the loss or detriment might be directly or indirectly attributed to the actions of friends, family or associates of a victim; or to community members generally. For example, where an offender takes part in a robbery, is then savagely beaten by friends of the victim, and suffers serious injuries as a result.3

Or, where an elderly man committed a sexual offence against a girl and then suffered, along with his wife, a campaign of abuse and harassment, involving threats of serious injury to person and property. Where that campaign caused the offender to be admitted to a psychiatric clinic for treatment, and caused the couple to leave their home and live elsewhere under assumed names.4

Or, where an elderly man committed a sexual offence against a girl and then suffered, along with his wife, a campaign of abuse and harassment, involving threats of serious injury to person and property. Where that campaign caused the offender to be admitted to a psychiatric clinic for treatment, and caused the couple to leave their home and live elsewhere under assumed names.4

Or, where a truck driver drove dangerously causing the deaths of two people, and grievous bodily harm to two others. Where that driver suffered a high degree of unresolved trauma as a result of the deaths and injuries, and threats and harassment from the victims’ families, and where those circumstances inadvertently led to the loss of his business and home.5

A further example is where an Aboriginal offender, suffers, or can expect to suffer some traditional punishment or ‘payback’.

III CAN EXTRA-CURIAL PUNISHMENT MITIGATE SENTENCE?

Extra-curial punishment is not expressly referred to in the Penalty and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld). (‘the Act’) Nonetheless, both legislation and common law provides that facts amounting to extra-curial punishment might be taken into account on sentence.

Section 9(2) of the Act provides that in sentencing an offender, a court must have regard to certain specific matters, including:

‘(g) the presence of any aggravating or mitigating factor concerning the offender; and …(r) any other relevant circumstance.’

Clearly, serious loss or detriment suffered by an offender as a result of having committed an offence, may be relevant under either sub-section.

The common law also provides that a sentencing court has power to take into account any mitigating factors. Indeed, a sentencing court should consider all mitigating and aggravating circumstances. In Neal v The Queen, Murphy J reckoned that credit should be given for mitigating factors in all but exceptional circumstances. He said:

Where there is no specific justification for with-holding credit for mitigating factors the sentencer will be expected to make an appropriate reduction. Not to do so is an exceptional course limited to those cases where there are other considerations such as the prevention of further offences, which are compelling.6

Finally, the Australian Law Reform Commission noted a further basis upon which extra-curial punishment might be considered. The Commission recorded that there is an important common law principal that a person not be punished twice for the same offence.7

This principal must also be considered in light of s 16 of the Criminal Code 1899 (Qld). (‘the Code’) This section enshrines the above principal, saying:

‘[a] person cannot be twice punished either under the provisions of this Code or under the provisions of any other law for the same act or omission …’

Applying this section, the Queensland Court of Appeal found that a child’s expulsion from school for misconduct, did not amount to punishment for the purposes of the section. Therefore, the criminal justice system could further deal with the child for that misconduct.8 Mackenzie J opined:

There is a well established principle that regimes which regulate behaviour within an organisation do not involve punishment in their relevant sense. … But the fact the person suffers a detriment and may consider it to be punishment does not mean that it is punishment for the purposes of s 16.9

It is argued that because some detriment is not punishment for the purposes of s 16, this does not mean it ought not be taken into account by a sentencing court. Such detriment remains a relevant consideration under the Act and common law principals, and may thereby mitigate penalty.

IV HOW MIGHT EXTRA-CURIAL PUNISHMENT BE USED TO MITIGATE SENTENCE

There are several basis upon which extra—curial punishment might be used to mitigate a judicial sentence. For example, such punishment may:

A. instil genuine remorse;

B. punish in its own right;

C. deter the offender from the same or similar conduct; or,

D. deter others from the same or similar conduct.

A. Instilling Genuine Remorse

Remorse (or contrition) is a matter that the Act says must be taken into account on sentence.10

Remorse (or contrition) is a matter that the Act says must be taken into account on sentence.10

An example of how extra-curial punishment might lead to remorse was described by Judge Woods, the judge at first instance, as reported in Daetz. He had said:

The effect, as I see it, that may properly be given in the present case to … the acknowledged fact that he (Daetz) was, in fact, injured as I have described is that: that, no doubt, he is contrite and, no doubt, he has a deeper understanding of the position of being the victim of an offence than otherwise he might have had.11

His Honour had gone on to say:

… I have allowed a substantial discount, and will allow a substantial discount, for contrition. But I do not allow any separate mitigatory effect by way of reduction of the sentence which I will otherwise impose due simply to the fact that he has had his skull fractured in a revenge attack after he, himself, had been engaged in a violent and vicious attack on a person.12

This last mentioned ruling, was disapproved by the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal (IV B below).

B. Punishing In Its Own Right

The Act states one of the purposes for which sentences are imposed is to punish an offender to an extent and in a way that is justified in the circumstances.13

In Daetz, Justice James, after thoroughly reviewing previous authorities, said:

I have concluded … that, while it is the function of the courts to punish persons who have committed crimes, a sentencing court, in determining what sentence it should impose on an offender, can properly take into account that the offender has already suffered some serious loss or detriment as a result of having committed the offence. This is so, even where the detriment the offender suffered has taken the form of extra-curial punishment by private persons exacting retribution or revenge for the commission of the offence. In sentencing the offender the court takes into account what extra-curial punishment the offender has suffered, because the court is required to take into account all material facts and is required to ensure that the punishment the offender receives is what in all the circumstances is an appropriate punishment and not an excessive punishment.14

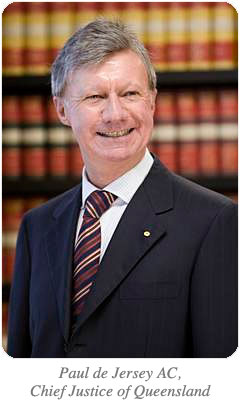

The Queensland Court of Appeal approved the above reasoning in R v Hannigan15. That was an appeal against sentence in which Chief Justice de Jersey joined with Justice Chesterman in a majority judgement (V below).

C. Deterring The Offender From The Same Or Similar Conduct

The Act states one of the purposes for which sentences are imposed is to deter the offender or other persons from committing the same or a similar offence.16

The possibility of extra-curial punishment deterring an offender was specifically recognised by Justice Chesterman in Hannigan:

In my opinion the theory which underlies the reliance of extra-curial punishment to sentence is that it deters an offender from re-offending by providing a reminder of the unhappy consequence of criminal misconduct, or it leaves the offender with a disability, some affliction, which is a consequence of criminal activity. In such cases one can see that a purpose of sentencing by the court, deterrence or retribution, has been partly achieved.17

D. Deterring Others From The Same Or Similar Conduct

The Act states one of the purposes for which sentences are imposed is to deter the offender or other persons from committing the same or a similar offence.

It might be argued, though less forcefully, that others learning of the loss or detriment suffered by offenders in the aftermath of an offence, might also be deterred from the same of similar offending conduct.

V THE POSITION IN QUEENSLAND

In Hannigan, the Queensland Court of Appeal articulated the position in Queensland.

The case involved an offender sentenced for dangerous operation of a vehicle while adversely affected by an intoxicating substance. During a police car chase the offender’s vehicle was damaged in a collision with a medium strip and traffic sign. The vehicle later stopped as a result of the damage. A witness to subsequent events deposed that:

The case involved an offender sentenced for dangerous operation of a vehicle while adversely affected by an intoxicating substance. During a police car chase the offender’s vehicle was damaged in a collision with a medium strip and traffic sign. The vehicle later stopped as a result of the damage. A witness to subsequent events deposed that:

I witnessed the Police Officer vigorously punching the face of the person in the utility and swearing at him to, ‘get out of the fucking car, cunt’ several times. … he only punched the person, I would say, in excess of twenty times. … I am a 46 year old woman who has never witnessed such sickening violence against another human being. I am absolutely in fear of the policeman and felt ill from seeing such unfettered brutality against another person.

The witness and statement only came to light after sentencing. On appeal, Justice Chesterman found that the applicant had no recollection of the incident and was unaware he had been struck. Any injuries were minor and their effect went unnoticed and in any event would have been transient.18

His Honour ignored certain evidential and procedural matters in order to determine the substantive issue: whether the alleged assault upon the offender, if known to the sentencing judge, should have mitigated penalty?19

While accepting the mitigating force of extra-curial punishment (IV C above), his Honour found that it was not available in that case. After quoting the portion of Daetz noted at IV B above, he said, ‘[i]t is in my opinion, significant that His Honour referred to an offender suffering “serious loss or detriment as a result of having committed the offence.”’20

He went on to review a number of authorities and the alleged circumstances and injuries in the instant case. He then continued:

This consideration (deterrence or retribution) does not apply to the applicant who felt no pain from the blows because he was effectively anesthetized by the alcohol he had consumed, and who has no persisting symptoms to remind him of the folly of driving when drunk. The applicant cannot be regarded as having undergone punishment at the hand of the police officer when he himself was oblivious to the castigation and its aftermath.21

It appears then, that for extra-curial punishment to have any mitigating effect in Queensland, it must be sufficient to deter the offender from re-offending. That is, it must result in serious loss or detriment, sufficient to remind an offender of the unhappy consequence of offending.

VI OTHER CONSIDERATIONS LIMITING THE AVAILABILITY OF MITIGATION

Justice Chesterman noted two further considerations when determining if extra-curial punishment should mitigate penalty.

Firstly, he gave effect to the exception contemplated by Murphy J in Neal (III above). Chesterman noted that a punishment that distinctly deters was particularly important in Hannigan’s case. He referred to the offender’s appalling traffic history, previous drink driving, and the fact he was unlicensed, grossly intoxicated and driving in a highly dangerous manner when pursued by police. He opined that if offenders of this type are not punished severely, the offending will likely continue with tragic consequences being almost inevitable. He said, ‘[t]he punishment imposed on the applicant was apt to persuade him of the seriousness of his behaviour and to provide a sound incentive to reform. It served to protect the public.’22

Firstly, he gave effect to the exception contemplated by Murphy J in Neal (III above). Chesterman noted that a punishment that distinctly deters was particularly important in Hannigan’s case. He referred to the offender’s appalling traffic history, previous drink driving, and the fact he was unlicensed, grossly intoxicated and driving in a highly dangerous manner when pursued by police. He opined that if offenders of this type are not punished severely, the offending will likely continue with tragic consequences being almost inevitable. He said, ‘[t]he punishment imposed on the applicant was apt to persuade him of the seriousness of his behaviour and to provide a sound incentive to reform. It served to protect the public.’22

Secondly, the notion of somehow sanctioning the perpetrator of the extra-curial punishment should play no part in the process of sentencing the original offender. The process of disciplining, prosecuting or otherwise sanctioning the conduct of the architect of the extra-curial punishment must be considered quite separately. There exists legitimate means to achieve this, including for example, disciplinary or civil action, or a criminal prosecution.23

VII WHERE AVAILABLE, HOW MUCH MITIGATION MIGHT BE AFFORDED BY EXTRA-CURIAL PUNISHMENT?

How much mitigation might be afforded by extra-curial punishment is a matter of fact and circumstance.

The court in Daetz stated:

How much weight a sentencing judge should give any extra-curial punishment will, of course, depend on all the circumstances of the case. Indeed, there may well be many cases where extra-judicial punishment attracts little or no significant weight.24

The statement was cited with approval in Hannigan.25

In Daetz a sentence of six years with a non-parole period of three years was substituted by a sentence of five and a half years with a non-parole period of two years nine months.

In R v Shane Thomas Davidson, Judge Dearden sentenced an offender who had committed a relatively low range indecent treatment offence against a ten year old boy.26 Immediately after the offence there was what his Honour described as ‘… an utterly catastrophic response …’ by the boy’s father. Davidson was savagely beaten leaving him with serious head injuries requiring surgical reconstruction of much of his face. He suffers permanent facial deformity, cognitive deficits and chronic post traumatic headaches. His Honour imposed a nine month intensive correction order in circumstances where, but for the extra-curial punishment, he would have imposed a sentence of twelve months including a period of actual imprisonment.

It seems then, that in appropriate circumstances the mitigating effect of extra-curial punishment might be significant. By way of contrast, in Sharpe v R27 the court was not satisfied that injuries sustained by the applicant should have led to any reduction in sentence. In that case the offender was shot in the leg by a security guard protecting property. He was said to have endured a passing physical injury and four days hospitalisation. There was a suggestion of post-traumatic stress disorder unsupported by satisfactory evidence. The court opined that ‘Even if these circumstances attracted the extra-curial punishment principle, this evidence would provide very little assistance to the Appellant on sentence…’28

VIII CONCLUSIONS

Both the Penalty and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld) and the common law provide a basis for extra-curial punishment to be considered by a sentencing court.

There are a number of ways in which it might be argued that extra-curial punishment should mitigate a judicial sentence. Extra-curial punishment might: instil genuine remorse; punish in its own right; and, deter the offender and others.

How much mitigation is afforded an offender is a matter of fact and circumstance. In some cases the mitigation may be substantial.

Where extra-curial punishment exists, a sentencing court will be expected to make an appropriate reduction in sentence, unless there are other compelling considerations.

Frank Richards

Footnotes

- R v Fletcher a Victorian Court of Appeal decision discussed in a note by F Rinaldi in (1980) 4 Crim LJ 244.

- Alameddine v R [2006] NSWCCA 317.

- R v Daetz (2003) 139 A Crim R 398 (‘Daetz’)

- R v Allpass (1993) 72 A Crim R 561.

- R v Clampitt-Wotton [2002] NSWCCA 383.

- Neal v The Queen (1982) 149 CLR 305 at 319.

- Aboriginal Customay Laws (ALRC 31) tabled 12 June 1986 at paragraph 508.

- R v NG [2006] QCA 218 (Regarding this point, an application for special leave to appeal to the High Court was refused. NG v The Queen [2006] HCATrans 671) .

- [2006] QCA 218 at paragraph 78.

- S(4)(i).

- (2003) 139 A Crim R 398 at paragraph 26.

- Ibid.

- S9(1)(a).

- (2003) 139 A Crim R 398 at paragraph 62.

- [2009] QCA 40 at paragraph 15 (‘Hannigan’).

- S9(1)(c).

- [2009] QCA 40 at paragraph 25.

- Ibid at paragraph 15.

- Ibid at paragraph 14.

- Ibid at paragraph 16.

- Ibid at paragraph 25.

- Ibid at paragraphs 27.

- Ibid at paragraphs 28 and 29.

- (2003) 139 A Crim R 398 at paragraph 62.

- [2009] QCA 40 at paragraph 15.

- Beenleigh District Court 15 June 2009.

- [2006] NSWCCA 255.

- Ibid at paragraph 67.

The law and medicine now share common challenges. Over the latter part of the last century, some of the basic elements of the professions were questioned, and they continue to be so. Some have asserted that the professions have exploited their monopolies: for the medical specialists, for example, it is asserted that the specialities have restricted the numbers admitted to the profession; of the lawyer it is said that a monopoly over this essential service has caused the administration of the law to become too expensive. It has been said that the doctors and lawyers have abused collegiality to protect the incompetent or the unethical. And, perhaps most importantly, both the law and medicine have been criticised for failing, or at least falling short, in their roles as self regulators.

The challenges that we face have parallels in effect. Both professions have now ceded ultimate disciplinary control to “boards”, or “commissions”. Doctors have state, and perhaps soon national medical boards. There is now a legal services commission in all states of Australia, with power to investigate and prosecute those who fall short of acceptable professional standards. This is a kick in the pants for both professions, although ultimately not a matter which will directly affect many of us. Yet most of you, like us, would have been uncomfortable with this “intrusion”, and with the notion that lay members or observers would have some role in determining the outcome of complaints.

The challenges that we face have parallels in effect. Both professions have now ceded ultimate disciplinary control to “boards”, or “commissions”. Doctors have state, and perhaps soon national medical boards. There is now a legal services commission in all states of Australia, with power to investigate and prosecute those who fall short of acceptable professional standards. This is a kick in the pants for both professions, although ultimately not a matter which will directly affect many of us. Yet most of you, like us, would have been uncomfortable with this “intrusion”, and with the notion that lay members or observers would have some role in determining the outcome of complaints.

The medical profession has for centuries had a greater degree of control over admissions to practise than has the legal profession. The colleges, as conduits to medical specialty, have proven much more enduring than Lincoln’s Inn, Grays Inn and the other Inns in Chancery Lane. However, the monopolies that the professions had on training, admission and on the areas of practice traditionally regarded as the province of doctors, lawyers and indeed the courts have been substantially eroded. In the medical profession, the colleges now permit admission under greater external influence than in the past; and many procedures and tasks traditionally performed by doctors are now performed by paramedics and other “health carers”. In the law, barristers and solicitors have for the most part retained their “turf”, but in litigation there has been a significant “outsourcing” of the means by which the community resolves its disputes. The huge growth in alternative dispute resolution, in mediation, is a direct consequence of the inability of the lawyers to provide inexpensive but effective dispute resolution through litigation. There is a sound view that litigation is beyond almost all bar wealthy corporate entities and individuals, and otherwise those who litigate with the benefit of no win no fee arrangements. The latter category of litigant is confined, in practice, to personal injuries litigation, where outcomes are relatively predictable, and the number of cases high. Mediation, on the other hand, is relatively inexpensive: it gives rise, technically, to an inferior outcome — a fuzzier outcome in legal terms — but it is cheap. At the highest level, the court, there has also been a significant outsourcing of work: long law lists in the newspaper may now be found for the multitude of tribunals hearing the smallest to some of the biggest cases in the State.

The medical profession has for centuries had a greater degree of control over admissions to practise than has the legal profession. The colleges, as conduits to medical specialty, have proven much more enduring than Lincoln’s Inn, Grays Inn and the other Inns in Chancery Lane. However, the monopolies that the professions had on training, admission and on the areas of practice traditionally regarded as the province of doctors, lawyers and indeed the courts have been substantially eroded. In the medical profession, the colleges now permit admission under greater external influence than in the past; and many procedures and tasks traditionally performed by doctors are now performed by paramedics and other “health carers”. In the law, barristers and solicitors have for the most part retained their “turf”, but in litigation there has been a significant “outsourcing” of the means by which the community resolves its disputes. The huge growth in alternative dispute resolution, in mediation, is a direct consequence of the inability of the lawyers to provide inexpensive but effective dispute resolution through litigation. There is a sound view that litigation is beyond almost all bar wealthy corporate entities and individuals, and otherwise those who litigate with the benefit of no win no fee arrangements. The latter category of litigant is confined, in practice, to personal injuries litigation, where outcomes are relatively predictable, and the number of cases high. Mediation, on the other hand, is relatively inexpensive: it gives rise, technically, to an inferior outcome — a fuzzier outcome in legal terms — but it is cheap. At the highest level, the court, there has also been a significant outsourcing of work: long law lists in the newspaper may now be found for the multitude of tribunals hearing the smallest to some of the biggest cases in the State.

There is no doubt a legitimate public interest in these interventions. The large sum of public money spent on health care and the legal system is reason enough. Moreover, although we may not like it, we must concede that in some important respects law, and medicine, have failed in a fast changing environment to keep close the values fundamental to a profession.

How best do our professions position themselves for the future? It would be naive to think that there have not been tectonic changes to the way in which we go about our work, and that those changes are reversible. But not all change is bad, and change is seldom as bad as we fear it might be. The changing circumstances in fact present opportunities to return to values that we have long held dear, and better to carry out expectations which have long been held of us.

Can I put to you that the single greatest threat to the medical profession, and to the legal profession, is public mistrust? Minds will differ as to whether, and if so to what extent, but that is not really the point. In the case of the medical profession, the principal element of mistrust goes to competence: the perception perpetrated by a willing media, accepted by some members of the public, that the profession, and the regulatory bodies, have been unable to ensure that all medical practitioners have the requisite degree of competence. It is trite now to talk of the Bristol affair or, whatever the rights and wrongs of the criticisms of Bundaberg Hospital, but examples of that nature have a significant impact on the public’s perception of professional standards, and upon the reliability of the profession in regulating entrance to its ranks. In the case of lawyers issues going to competence undoubtedly exist, but do not seem to attract the same public attention, perhaps because fewer have contact with the legal system, and because it is more difficult, in contested litigation, to identify the bad outcome. The single most important issue for lawyers in the context of public mistrust is cost, and the rather disturbing proposition that the majority of our citizens cannot afford to go to Court.

Can I put to you that the single greatest threat to the medical profession, and to the legal profession, is public mistrust? Minds will differ as to whether, and if so to what extent, but that is not really the point. In the case of the medical profession, the principal element of mistrust goes to competence: the perception perpetrated by a willing media, accepted by some members of the public, that the profession, and the regulatory bodies, have been unable to ensure that all medical practitioners have the requisite degree of competence. It is trite now to talk of the Bristol affair or, whatever the rights and wrongs of the criticisms of Bundaberg Hospital, but examples of that nature have a significant impact on the public’s perception of professional standards, and upon the reliability of the profession in regulating entrance to its ranks. In the case of lawyers issues going to competence undoubtedly exist, but do not seem to attract the same public attention, perhaps because fewer have contact with the legal system, and because it is more difficult, in contested litigation, to identify the bad outcome. The single most important issue for lawyers in the context of public mistrust is cost, and the rather disturbing proposition that the majority of our citizens cannot afford to go to Court.

Mistrust of this nature goes to the heart of our identities as professions, as opposed to commercial service providers. And we are not just commercial service providers. We must ask ourselves, it seems to me, how to remedy the mistrust, and move our professions forward with the times.

Can I suggest these questions and touchstones?

First, are our professional associations and regulatory authorities doing everything necessary to ensure the quality of our standards and, importantly, are we as members recognising the necessity to respond positively and cooperatively to sensible reform. Under the present regulatory regimes for both professions, the professional associations may regulate the continuing right to practice by the imposition of conditions. In the case of some medical specialities, for example, colleges are insisting upon members providing information and results permitting performance audit. Performance audit is for many a sensitive topic, an intrusion which, whatever your results, feels unwelcome. That is understandable, yet may I suggest the response of our professions to reforms of this nature lies at the heart of our ability to maintain public trust, and our continued, relative, autonomy. And can I comfort you with these observations concerning audit? A barrister’s court work is carried out, in public, before a judge, and in front of her peers. There is for the bar a very public process of audit, and we have long survived it. If one means of identifying outliers, and perhaps enhancing professional standards more generally, is for surgeons to submit to the process of audit in a way which is protected by confidentiality, why not embrace it? There is no more fundamental professional responsibility than the provision of competent services. This, in the modern day, surely involves not only adequate training and continuing education but also willingness on the part of the professions to embrace processes of audit designed to identify problems and hence permit a means of remedying them. Another measure, the subject of statute in New South Wales, and soon to be introduced to the Queensland Parliament, imposes upon medical practitioners a positive, ethical duty to report to the medical board the incompetent fellow practitioner. The obligation under the Queensland proposal is broader than in New South Wales. A positive reporting obligation now exists, in one form or another, on some legal practitioners overseas and there must be a sensible prospect over time that legislation will be passed here with the same object. The notion of such an obligation is confronting, and the circumstances in which such an obligation might arise need carefully to be considered and defined. But these are the sorts of issues that the professional bodies should consider before clumsy legislative enactments make it unnecessary to do so. The key object is the maintenance of public trust in the profession, and in its ability responsibly and effectively to protect its standards and to manage and regulate itself.

First, are our professional associations and regulatory authorities doing everything necessary to ensure the quality of our standards and, importantly, are we as members recognising the necessity to respond positively and cooperatively to sensible reform. Under the present regulatory regimes for both professions, the professional associations may regulate the continuing right to practice by the imposition of conditions. In the case of some medical specialities, for example, colleges are insisting upon members providing information and results permitting performance audit. Performance audit is for many a sensitive topic, an intrusion which, whatever your results, feels unwelcome. That is understandable, yet may I suggest the response of our professions to reforms of this nature lies at the heart of our ability to maintain public trust, and our continued, relative, autonomy. And can I comfort you with these observations concerning audit? A barrister’s court work is carried out, in public, before a judge, and in front of her peers. There is for the bar a very public process of audit, and we have long survived it. If one means of identifying outliers, and perhaps enhancing professional standards more generally, is for surgeons to submit to the process of audit in a way which is protected by confidentiality, why not embrace it? There is no more fundamental professional responsibility than the provision of competent services. This, in the modern day, surely involves not only adequate training and continuing education but also willingness on the part of the professions to embrace processes of audit designed to identify problems and hence permit a means of remedying them. Another measure, the subject of statute in New South Wales, and soon to be introduced to the Queensland Parliament, imposes upon medical practitioners a positive, ethical duty to report to the medical board the incompetent fellow practitioner. The obligation under the Queensland proposal is broader than in New South Wales. A positive reporting obligation now exists, in one form or another, on some legal practitioners overseas and there must be a sensible prospect over time that legislation will be passed here with the same object. The notion of such an obligation is confronting, and the circumstances in which such an obligation might arise need carefully to be considered and defined. But these are the sorts of issues that the professional bodies should consider before clumsy legislative enactments make it unnecessary to do so. The key object is the maintenance of public trust in the profession, and in its ability responsibly and effectively to protect its standards and to manage and regulate itself.

On a different but related topic, our professional organisations must be careful indeed when on the one hand representing members, and on the other hand performing public roles. Medical associations have a responsibility to speak out on matters concerning the public health system, such as insufficient funding, or the rise of the influence hospital administrators applying economic rather than clinical criteria for treatments; and Bar Associations have a responsibility to speak out about unjust laws, and the legal system and processes. Our professional bodies also have a role in advancing the interests of members, although we and they need to be mindful that there may be a conflict between these roles. Where the interests of a member or members collectively conflict with the public interest, which interest for our professional organisations should prevail? I would suggest, in an immediate sense, that it is the public interest which should prevail, yet that answer is not entirely fulsome, because it is our acting in the public interest which maintains public confidence, and the confidence of the public is ultimately in the interests of the professions.

Finally, it is important that those studying to be lawyers and doctors be taught about the values of the professions, and professional ethics. Do we, do modern students of the law and medicine, understand the importance of the implicit social contract which, historically, lies at the heart of the true professions: that the right granted by the community, to us alone, to practise in medicine and the law requires us to act not only in the interests of our patients and clients, but in matters concerning our system of health care and the administration of justice, also in the interests of the public?

Roger Traves SC

You are invited to dicsusion your opinions on this article in the Hearsay Forum …

Perhaps equally concerning, the study demonstrated that amongst the professionals surveyed there was a lack of understanding of the complexity of the causes and treatment of depressive conditions. Respondents to the survey stated that individuals suffering from depression could be assisted by going on a holiday, going to the pub for a few drinks with friends or identifying and removing the cause of depression.2

Although these remedies may be of assistance for someone who is simply having a normal emotional reaction to setbacks and stressors, they are unlikely to be of assistance and could be counterproductive in the setting of a depressive illness.3 Depressive illnesses are more than simply having ‘a bad day’ and even with optimal treatment can be temporarily or permanently disabling, and without treatment, fatal.

A number of validated treatment methods can be applied, depending on the nature and intensity of the depressive condition. In the absence of proper diagnosis and treatment, long-term physical and emotional health risks and vocational impairment can arise from depressive illness.

With improved community awareness and general practitioner vigilance, people sensibly seek help for emotional problems. In doing so, many are formally diagnosed with a depressive illness and provided with appropriate treatment. However, it is of concern that because of this history of successfully treated illness, some individuals subsequently suffer disadvantage and discrimination when seeking to obtain certain types of insurance.

What is “Depression”?

What is “Depression”?

“Depression” is a generic, non-clinical term which encompasses a number of mental illnesses of variable intensity known as mood disturbances or disorders. It is beyond parameters of this article to provide a detailed study of the diagnostic features of each of the depressive disorders. However, it is helpful to the lay reader to be provided with an overview of the clinical presentation of depressive conditions.

The most serious mood disorder, “Major Depressive Disorder” is comprised by one or more episodes of illness, each being defined by The American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV4 as:

- The presence of five or more of the following symptoms during the same two week period where the presence of the symptoms represent a change from previous functions:

o Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day;

o Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day;

o Significant unintentional weight loss or gain;

o Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day;

o Objective presentation of psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day;

o Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day;

o Feelings of worthlessness or excessive inappropriate guilt nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick);

o Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness nearly every day;

o Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide.

- The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning;

- The symptoms are not due to the psychological effects of a substance or a general medical condition; and

- The symptoms are not better accounted for by bereavement.

Depressed mood caused by the following conditions is excluded from this definition of Major Depressive Disorder:

- hypomania (Bipolar Disorder or “manic depression”)

- substance abuse (e.g. alcohol, amphetamines or other drugs)

- general medical conditions (e.g. low thyroid gland function).5

This distinction is made because Bipolar Disorder (and the lesser-intensity Cyclothymic Disorders) are characterised by complex symptoms involving both depression-like symptoms and mood elevation or irritability and complicated by dysfunctional behaviours (e.g. excess poorly goal-directed activity; decreased need for sleep; impulsive, unusual risk taking behaviour).6 They are also considered to have possible genetic and seasonal onset differences.

The next most serious mood disorder is Dysthymic Disorder. This condition is usually characterised by symptoms of depressed mood that persist for longer periods (at least two years) but are often not as severe as those experienced during a Major Depressive Episode or Major Depressive Disorder.7 Sometimes, this type of lower grade mood disturbance has been present since adolescence or early adulthood.

The next most serious mood disorder is Dysthymic Disorder. This condition is usually characterised by symptoms of depressed mood that persist for longer periods (at least two years) but are often not as severe as those experienced during a Major Depressive Episode or Major Depressive Disorder.7 Sometimes, this type of lower grade mood disturbance has been present since adolescence or early adulthood.

Generally speaking, individuals who might be experiencing a depressive illness complain of or exhibit some of the following behaviours:

- Moodiness that is out of character;

- Concentration difficulties or complaints of forgetfulness;

- Increased irritability and frustration;

- Inability to accept personal criticism;

- Withdrawal from family and friends;

- Loss of interest in food, sex, exercise or other pleasurable activities;

- (Possible) Increased use of alcohol or drugs;

- Markedly diminished motivation for work or unusual feelings of being overwhelmed by work;

- Increased fatigue, pain or general ill health; or

- Slowing of thoughts and actions.8

Considerable diagnostic vigilance should be exercised by medical practitioners to exclude underlying general medical conditions. In part, this is the reason that psychologists received referrals from general practitioners rather than ab initio.

Depression and Personal Insurance

The purpose of insurance is to transfer the financial risks associated with the occurrence of a particular event from one person to a group of persons or a corporation better able to collectively bear the identified risk. The insurer, when deciding whether to accept the risk (and the premium price) needs to assess the likelihood of the event occurring. For this reason there are duties on parties seeking insurance to act in good faith9 and to make full disclosure of any matters that may be relevant to the insurer’s decision to accept the risk.10

Mental illness represents a significant proportion of payments made under personal insurance premiums. In 2006, 25% of payments made by insurers under Income Protection policies and 20% of payments made in Total and Permanent Disability claims related to mental health conditions.11 In part, this is a reflection of the prevalence of these conditions in the general population (e.g. the 1997 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing by the Australian Bureau of Statistics identified that 6% time of males and 8.5% of females in the 35-44-year-old age group suffered from depression. Importantly , a Canadian study of 25-44-year-old males and females found mean durations of major depressive illness of 6.4 and 9.2 months respectively12.

It follows that, at least as far as insurers are concerned, individuals with a history of depressive illness represent an increased risk in the areas of personal insurance, that is, life, health, income protection, trauma and disability insurances. It is for this reason that for some time it has become more difficult for those with a history of depressive illness to obtain some types of personal insurance. Discrimination by insurers in this way is specifically excluded from Anti-Discrimination legislation.13 It has also been difficult for individuals who have been insured for income protection or disability to successfully claim and there are sensational United States reports of abuses14.

Since July 2001, the life insurance industry and mental health organisations have been working to improve the prospects of obtaining personal insurance for individuals suffering from mental illness. This collaboration resulted in a Memorandum of Understanding which was first signed in 2003 and most recently updated in 2008.15 A report published in October 200816 provides details of the changes in underwriting practices that have been achieved since the introduction of the Memorandum of Understanding.

Since July 2001, the life insurance industry and mental health organisations have been working to improve the prospects of obtaining personal insurance for individuals suffering from mental illness. This collaboration resulted in a Memorandum of Understanding which was first signed in 2003 and most recently updated in 2008.15 A report published in October 200816 provides details of the changes in underwriting practices that have been achieved since the introduction of the Memorandum of Understanding.

Essentially, the data presented in the report indicates that although the issue of standard policies to individuals with a history of mental illness has only increased slightly, the number of applications for Total and Permanent Disability insurance which have been declined has reduced from 50% to 30% and the number of applications for Income Protection insurance which have been declined has reduced from 65%to 25%.17 It is becoming more common, then for insurers to issue policies albeit with increased premiums or exclusions applying to claims relating to mental illness. The authors of the report go on to say that:

“In 2007, the underwriting survey sought to assess what impact the severity of conditions had on underwriting outcome. The results showed that applicants are more likely to obtain cover when the condition is situational or experienced for short durations.”18

In summary, insurers have become increasingly sophisticated in their actuarial assessment of risks associated with depressive and other mental illness; indeed, it may be possible to negotiate personal insurances depending on individual circumstances. Individual insurance companies that are signatories to the Memorandum of Understanding are ING Life, Swiss Re Life and Health, AMP and AXA Australia.19

Depression and Professional Indemnity Insurance

The fact that a diagnosis or history of depressive illness impacts upon an individual’s ability to obtain personal insurance raises questions in relation to Professional Indemnity insurance. Namely:

1. Whether a barrister who has suffered from or been diagnosed with a depressive illness is required to disclose that fact to his or her Professional Indemnity insurer; and

2. Whether an insurer will limit or preclude cover based on such a diagnosis.

I have spoken with Mr Brian Readdy of Suncorp, Mr Robert Cooper of Aon and Mr Jacques Moritz of Marsh and posed those two questions to each of them.

It also raises questions as to the level of disclosure required to the Bar Association of Queensland in relation to the annual issuance of a practising certificate. In the application form, Question 9 specifically enquires “Are you aware of any facts or circumstances which might affect your fitness to practise as a legal practitioner…?”. Similar regulatory enquiries are made to applicants for initial or re-registration in other professional groups (e.g. Medical Board of Queensland).

Disclosure

In relation to professional indemnity insurance, Mr Readdy, Mr Cooper and Mr Moritz all stated that there is no specific question on their companies’ proposal forms relating to the disclosure of clinical information and this would include information regarding depressive illness. Generally, they do not consider disclosure of clinical conditions, including depressive illness to be relevant or necessary.

All three informants stated that the only basis upon which disclosure may be required would be under the general duties of disclosure where the barrister considered or had received medical information to the effect that the condition was so severe that it impeded upon the barrister’s ability to perform his or her professional duties. If that were the case, however, there would be an obvious question over whether the barrister ought to be practicing at all if his or her ability to represent the client is so ostensibly impeded.

Impact on Cover

In an email to me Mr Moritz said that he was able to provide an “absolute assurance that premiums [in professional indemnity policies] are not increased or adjusted based on any medical conditions.” Although Mr Readdy and Mr Cooper did not go quite so far as to provide an assurance, they both expressed similar views that health issues are unlikely to impact upon cover for a professional risk. Further, the latter two insurance company representatives were not aware of any information indicating a correlation between depression and the manner in which a professional person carries out his or her profession.

In conclusion, then, it appears that a history of depressive illness is unlikely to affect a barrister’s ability to obtain Professional Indemnity insurance. However, the presence of depressive illness should always be considered by a barrister in relation to making a full and accurate disclosure to both insurers and regulatory bodies. If necessary, advice should be sought from treating medical practitioners and senior members of the Bar.

Although it has certainly been the case in the past that personal insurance has been denied to those with a history of mental illness, recent co-operative efforts between bodies representing mental health consumers and those in the insurance industry lay grounds for hope that this type of insurance is no longer entirely beyond reach.

Patricia Feeney

Footnotes

- Australian National Depression Initiative

- Beaton Consulting Annual Professions Survey Research Extract October 2007; Law Institute of Victoria Journal “Survey reveals depth of depression problem” June 2007; Law Institute of Victoria Journal “Depression figures prominently in the law” September 2007

- Dr Nicole Highet, Deputy CEO beyondblue, Law Institute of Victoria Journal “Survey reveals depth of depression problem” June 2007

- American Psychiatric Association “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders”th edition p327

- DSM-IV 4th edition p339 – 344

- For details of the diagnostic features of the full range of mood disorders see the chapter on “Mood Disorders” at p317 of DSM-IV

- DSM-IV 4th edition p345 – 346

- Law Institute of Victoria Journal “Survey reveals depth of depression problem” June 2007; see also www.beyondblue.org.au

- Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) s13

- Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) s21

- “Working towards positive life insurance outcomes for mental health consumers” Investment and Financial Services Association, Mental Health Council of Australia and beyondblue: the national depression initiative, October 2008

- Patten, SB (2001) The Duration of Major Depressive Episodes in the Canadian General Population. Chronic Diseases in Canada v22 No 1. pp 6-11.

- Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Qld) ss 74 and 75; Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) s46

- e.g. http://www.insulttoinjury.org/, accessed on 15 March 2009.

- Memorandum of Understanding between Mental Health Sector Stakeholders, the Investment and Financial Services Association and the Financial Planning Association, www.beyondblue.org.au

- “Working towards positive life insurance outcomes for mental health consumers” above

- “Working towards positive life insurance outcomes for mental health consumers” figure “Change in Underwriting outcomes for people with a mental health condition” p11

- “Working towards positive life insurance outcomes for mental health consumers” p13

- “Working towards positive life insurance outcomes for mental health consumers” p10

You are invited to dicsusion your opinions on this article in the Hearsay Forum …

Background

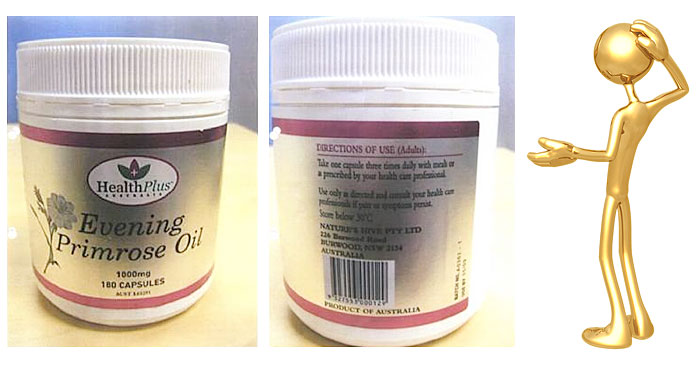

The litigation between two traders in the natural medicine field had been raging since 2001. The central question was whether the trade mark of the applicant (Health World), ‘Inner Health Plus’, which claimed a priority as a common law (or unregistered) trade mark, was deceptively similar to the registered trade mark ‘HealthPlus’ owned by the respondent (Shin-Sun).

There were three applications before the court. Two by Health World for the removal of the HealthPlus trade mark from the register and the third by Shin-Sun for restriction of the Inner Health Plus trade mark which was subsequently registered, to specific probiotic capsules.

Although several grounds entitling the removal were made out, the linchpin to such entitlement was Health World’s standing to make a complaint under s 88 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). As all three proceedings had been commenced prior to the commencement of the Trade Marks Amendment Act 2006, the provisions of the Act applied as they stood prior to the 2006 amendments: (the primary judge at [31])

Health World therefore had to show it was a ‘aggrieved person’, both for the purpose of s 88 and for its second application, the non-use application under s 92(1) and (3) of the Act, which required the ‘aggrieved person’ standing before the amendments.

The reasons of Jacobson J (upheld unanimously on appeal) on the questions of:

The reasons of Jacobson J (upheld unanimously on appeal) on the questions of:

- what constitutes an ‘aggrieved person’ for the purposes of s 88; and

- the circumstances when the Court might exercise discretion not to expunge the mark from the register under the discretion contained within s 88 or s 89,

are instructional but not the focus of this short comment. The observation made by this paper concerns the likely revocation of the Shin-Sun trade mark but for the lack of standing issue of Health World.

The Issue

If Health World had had standing, it would have succeeded on the following:

- The s 59 ground: Health World claimed that Shin-Sun did not intend to use or authorise the use of the HealthPlus trade mark in relation to the goods specified in the trade mark application: (reasons of the primary judge at [15] and [174]);

- The s 88(2)(c) ground: which provides that rectification may be sought on the ground that, by reason of the circumstances applying at the time of the application for rectification, the use of the registered trade mark is likely to deceive or cause confusion: (reasons of the primary judge at [18] and [182]).

The circumstances which gave rise to these findings are not uncommon. Shin-Sun was incorporated in 1993. Its directors were Mr James Shin and his wife, Mrs Anna Shin. Mr and Mrs Shin were the sole shareholders. Ms Theresa Shin was the general manager of Shin-Sun. She was the daughter of Mr James Shin and Mrs Anna Shin.

Nature’s Hive Pty Ltd was incorporated in 1995. Mr and Mrs Shin were also the directors of that company and Ms Theresa Shin owned twenty of the twenty-one issued shares. Her uncle owned the remaining share.

Ms Shin described the companies Shin-Sun and Nature’s Hive as family businesses, managed principally by her and her parents. In summary, Ms Shin was the General Manager of both companies but they had different shareholders: (the reasons at [60] — [66]).

Shin-Sun was the owner of the trade mark Health Plus, however it was Nature’s Hive who manufactured the natural medicines which were sold under the trade mark Health Plus. Further, the name and details on the bottles, was that of Nature’s Hive.2 His Honour therefore noted at [179]:

…at the date of the commencement of the rectification proceedings, the HealthPlus trade mark was used to identify the goods as those of Nature’s Hive, and not those of Shin-Sun…This would give rise to the likelihood of deception or cause confusion because of the failure to identify the registered owner as the source of the goods.

Trade mark law rests upon the ability of a trader to distinguish his or her goods or services from another trader by means of a ‘sign’. The failure of Shin-Sun to associate itself, the trade mark owner, with the goods would have been fatal to the mark. No doubt in the minds of the family, there was no difference between the manufacturer and the trade mark owner, however as noted by his Honour in relation to the evidence of Ms Shin at [171]:

the overall effect of her evidence was that she failed to distinguish between the two separate corporate entities, Shin-Sun and Nature’s Hive. I cannot be satisfied, and I find that she did not pay attention to which corporation she was representing when she took the steps that she relies upon to support the assertion that Shin-Sun intended to use the mark.

In my opinion, Shin-Sun has failed to discharge the evidentiary onus of satisfying the Court that it had a sufficiently clear and definite intention that Shin-Sun proposed to use the mark on goods within class 5 so as to establish a connection in the course of trade between Shin-Sun and the goods.

Isolated instance?

Isolated instance?

The impression appears to be that there may be an inclination to depart from the original purposes in setting up some commercialisation structures by virtue of the level of informality of the operators. Similarly in a recent case,3 Collier J concluded that the opposition succeeded on the s 59 ground, that there was no intention to use the mark in suit.

The basis of her Honour’s finding stemmed from the unclear ownership position of the trade mark in suit. This position was in large measure caused by the interchangeability of roles between the various corporate persona of one person, Mr Lawrence. That did not present a problem when the question of authorised use was considered, as her Honour concluded at [77]:

The evidence before me is that Mr Lawrence tended to confuse his own business interests with those of his companies, and appeared to randomly use companies and trade marks depending on the circumstances. In this respect I consider that it is open on the facts to find that all companies controlled by Mr Lawrence were authorised to use trade mark 967804.

Collier J was clear however, that the basis of the entitlement to lodge an application for a trade mark was ownership, not use, and ownership in this case was impossible to determine on the evidence: (her Honour’s reasons at [92]).

Conclusion

I would suggest that these cases highlight the need to establish clearly:

- Who owns the mark;

- What connection is made in the eyes of the public between the owner and the mark;

- The role of authorised users of the mark.

In this regard, although documented licence agreements will not cure substantive defects, they provide a helpful tool, guideline and starting point for trade mark owners and users as to the requirements on standing relevant to enforcement.

Dimitrios Eliades

Footnotes

- Health World Limited v Shin-Sun Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 100 (Jacobson J) (Healthworld); upheld on appeal in Health World Limited v Shin-Sun Australia Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 14 (Emmett, Besanko and Perram JJ): found at http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/FCA/2008/100.html

- See example of the Shin-Sun trade mark and product below.

- Television Food Network, G.P. v Food Channel Network Pty Ltd (No 2) [2009] FCA 271 (Collier J, 27 March 2009)

You are invited to dicsusion your opinions on this article in the Hearsay Forum …

You are invited to dicsusion your opinions on this article in the Hearsay Forum …

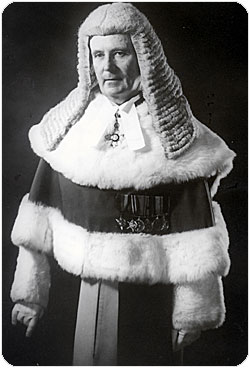

THE CHIEF JUSTICE

THE CHIEF JUSTICE

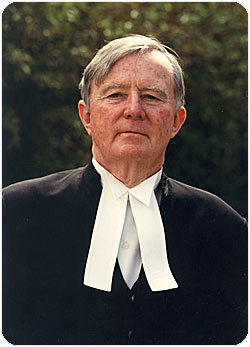

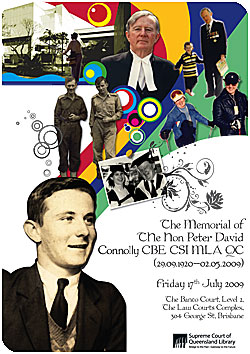

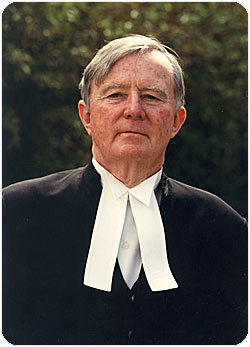

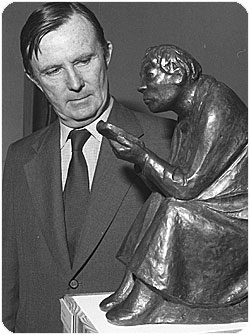

Ladies and gentlemen, we are going to acknowledge our gratitude for the judicial contribution of our former colleague, the Honourable Peter David Connolly CBE CSI who died on 2nd May 2009.

In acknowledging his singular judicial achievement, we express gratitude now on behalf of the people of Queensland to the members of his family, his children Claudia Jane, David, John and Zoe, and his long-term companion Mrs Paula Chandler.

I welcome the Honourable Attorney-General, heads and members of other Courts and tribunals, retired judges, and confirm that all judges of this Court, though some cannot be here today, would wish to join me in these following observations.

Four former judges have particularly requested me to do so; the Honourable Alan Demack and the Honourable Geoff Davies, together with the Honourable Bruce McPherson and the Honourable Glen Williams, both of whom are presently sitting in the Court of Appeal on the Solomon Islands.

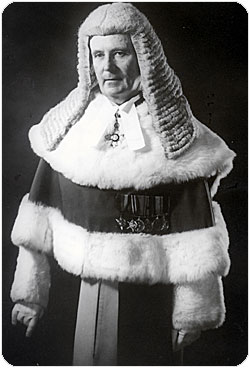

Peter Connolly was appointed to the Supreme Court on the 31st of October 1977 and remained a judge until his retirement on the 12th of September 1990, 17 days short of his 70th birthday.

Mr Justice Connolly came to the Court from a most distinguished prior career. He matriculated from St Joseph’s College in 1936 with the singular achievement of being bothDux and Head Boy. In 1948, he graduated from the University of Queensland as Bachelor of Laws with First Class Honours and was awarded a University Medal in an era when they were but sparingly accorded.

His brilliant career at the Bar spanned 28 years from 1949 and was characterised by intellectual and lawyerly eminence. Apart from a host of extringent commitments of Parliament, the Military, the Arts, he served as President of the Bar Association of Queensland, of the Australian Bar Association and of the Law Council of Australia.

His brilliant career at the Bar spanned 28 years from 1949 and was characterised by intellectual and lawyerly eminence. Apart from a host of extringent commitments of Parliament, the Military, the Arts, he served as President of the Bar Association of Queensland, of the Australian Bar Association and of the Law Council of Australia.

The year before his appointment as a judge, he was created Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his distinguished service to the legal profession. As well as serving as Judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland, Peter Connolly served from 1982 to 1994 as a Justice of Appeal in the Solomon Islands and as President for the last seven of those years, and from 1991 to 1998 as a Justice of Appeal in the Republic of Kiribati. His post nominals CSI refer to the Cross of the Solomon Islands. Extrajudicially, he served in 1996 to 1997 as Chair of the Connolly-Ryan Commission of Inquiry into the Criminal Justice Commission.

As a judge, Peter Connolly applied his high intellect, daunting command of legal principle and acute understanding of Court craft to the great benefit of litigants and the institution of the Court. He produced a raft of polished judgments not infrequently still quoted today. He abhorred laxity in legal and judicial reasoning and deplored any unnecessary dissent into subjectivity or so-called judicial activism or creativity. He was interested in the efficiency of litigation decrying sometimes volubly any wastage of time or other resources and producing reserved judgments without delay. He was an unswerving supporter of the institution of the Court and of the legal profession, and indeed, the Federal system of government of which he had an acute understanding.

As first speaker this morning, I have briefly focused on Peter Connolly’s judicial contribution. That was, however, but one facet of a human being of extraordinarily diverse talents and achievements.

His passing marks the departure of the last of the judges of the Supreme Court of Queensland who served in the Second World War which Peter Connolly accomplished with conspicuous gallantry. At lest it be pointed out, he was a greatly successful Queens Counsel, may be it should be recorded his interest in commensurately high fees was minimal.

As with his military career in particular, Peter Connolly’s legacy for the judicial government of Queensland was and is of heroic proportion. In noting his passing with great regret,we extend our sympathy to his children and Mrs Chandler and we are most grateful for their presence here today.

THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL

May it please the Court, I begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land where this Court is convened and pay my respects to their Elders, both past and present.

We gather here today to acknowledge the judicial career of the Honourable Peter David Connolly CBE CSI, who passed away on the 2nd of May this year. At the outset, I also wish to particularly acknowledge members of Peter Connolly’s family, his children, Claudia Jane, David, John and Zoe, and his partner, Mrs Paula Chandler.

Described as a Supreme Court Judge, politician and soldier, Peter Connolly had a diverse and impressive life dedicated to public service. Justice Connolly’s distinguished career began upon his return to Australia after service overseas in the Middle East, the Pacific and Southeast Asia during the Second World War. Peter Connolly returned to university in 1946 and studied law. He graduated with First Class Honours in 1948 winning the University Medal in Law. Before his graduation, he was appointed a lecturer in Constitutional Law at the University of Queensland. He was admitted to the Queensland Bar in 1949, and took silk in 1963.

Described as a Supreme Court Judge, politician and soldier, Peter Connolly had a diverse and impressive life dedicated to public service. Justice Connolly’s distinguished career began upon his return to Australia after service overseas in the Middle East, the Pacific and Southeast Asia during the Second World War. Peter Connolly returned to university in 1946 and studied law. He graduated with First Class Honours in 1948 winning the University Medal in Law. Before his graduation, he was appointed a lecturer in Constitutional Law at the University of Queensland. He was admitted to the Queensland Bar in 1949, and took silk in 1963.

Justice Connolly held the positions of President of the Bar Association of Queensland from 1967 to 1970, President of the Australian Bar Association from 1967 to 1968 and President of the Law Council of Australia from 1968 to 1970.

He also served overseas as a Justice of Appeal in the Republic of Kiribati and in the Solomon Islands.

Peter Connolly was appointed a Justice of the Supreme Court of Queensland in 1977 and served in that capacity for 13 years.

In 1976, he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his service to the legal profession.

He was widely regarded as having a formidable intellect, and was a traditional black letter lawyer from the old-school of strict, but unwaveringly fair judicial officers.

Peter Connolly’s erudite crystallisations of complex legal arguments are still utilised in our Courts, nearly 20 years after his retirement.

Prior to his passing, Justice Connolly was the last living Queensland Supreme Court judge to have served in the Second World War. He served between 1940 and 1946 in the Second Australian Imperial Force in the 2/12th Australian Infantry Battalion.

Justice Connolly saw service in the Middle East from 1940 to 1942; in New Guinea from 1942 to 1944; and in Morotai and Borneo in 1945 and 1946.

Upon his appointment to the Bench, Justice Connolly mentioned Sir Frederick Chilton as major influence on him, and one of the reasons he aspired to become a lawyer. Sir Frederick Chilton was a Sydney solicitor who commanded the 18th Brigade in which Justice Connolly served.

As Peter Connolly himself said, “I would first like to speak of somebody whose name is probably unknown to everybody here, and that is Sir Frederick Chilton, who commanded the 18th Brigade in which I had the honour to serve. He was a Sydney solicitor and he, more than anyone else, influenced me into the profession. He was a model of civilised behaviour, and I remember his displaying at the end of the War at Balikpapan a distaste for an attitude of petty vengefulness towards the defeated enemy, which was being actively encouraged by his superiors. It was the fashion, but he set his face against it.”

Peter Connolly continued his service upon returning to Australia, becoming Commanding Officer of the Queensland University Regiment; the 9th Battalion Royal Queensland Regiment; and of the Command and Staff Training Unit.

He was also elected to the Queensland Parliament as the State Member for Kurilpa from 1957 to 1960.

Through his military service, his election as a Member of the Queensland Parliament, and his distinguished judicial career, Peter Connolly’s life was one of committed public service.

Through his military service, his election as a Member of the Queensland Parliament, and his distinguished judicial career, Peter Connolly’s life was one of committed public service.

Peter Connolly also supported a large number of community organisations, mostly associated with the Arts. He was a Trustee of the Queensland Art Gallery from 1959 to 1983, and served as Vice President and President. As President, he said the Queensland Art Gallery should serve all people in Queensland, not just those in Brisbane.

He also served as a Director of the Queensland Opera Company, Queensland Convenor of the Committee on Education and the Arts in 1976 and 1977 and was President of Musica Viva Queensland.

I will conclude with a quote from Peter Connolly himself, which he made at his retirement valedictory ceremony. His words still ring true today, “Long before we become judges we are answerable to our conscience and to the law, but to no man. The characteristics of the profession are independence and individualism. We are, in the classic phrase, servants of all, yet of none.”

THE PRESIDENT OF THE BAR ASSOCIATION

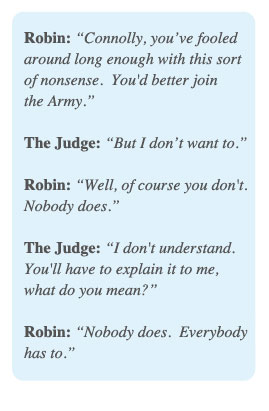

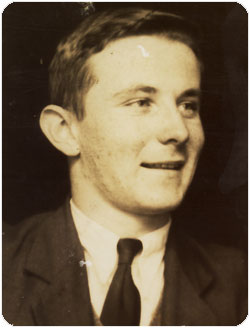

There is a story about the judge. It was in 1939 and he was studying Modern Languages at the University of Queensland. His generation knew towards the end of that year at the latest that there was a probability that they would have to fight and so knew that they faced the possibility of being killed. Having analysed the relevant facts, he had determined upon being a pacifist when his good friend, Brian Robin, confronted him. The conversation would have gone something like this.

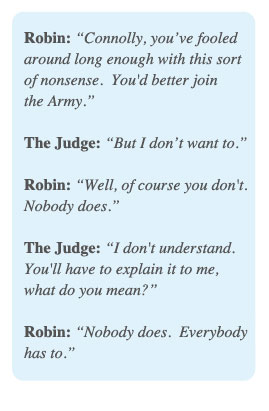

Robin: “Connolly, you’ve fooled around long enough with this sort of nonsense. You’d better join the Army.”

The Judge: “But I don’t want to.”

Robin: “Well, of course you don’t. Nobody does.”

The Judge: “I don’t understand. You’ll have to explain it to me, what do you mean?”

Robin: “Nobody does. Everybody has to.”