It is a privilege to speak at your Honour’s swearing in as the Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia.

Your Honour was always a shining light of the Queensland Bar, pre-eminent amongst us.

You were not long admitted before you developed a large practice in commercial and constitutional law. You were much sought after by our busiest and mot successful silks and you appeared many times in the High court led by the likes of Jackson QC, Davies and Thomas of Queens Counsel and, often for the Attorney-General for the State of Queensland, by de Jersey QC. In the important trade practices case of Queensland Wire Industries and BHP, your Honour appeared as junior to former Chief Justice Murray Gleeson and Byrne QC, now theSenior Judge Administrator of the Supreme Court.

Locally, your Honour had a wide ranging practice in and out of Court. Of note was your enviable retainer for the Proprietary Sugar Millers Association, for whom you appeared each Winter led by Hampson QC before the Central Sugar Cane Prices Board sitting in sunny regional Queensland.

As Queens Counsel Your Honour was one of those to whom juniors always looked but you gained a reputation for being one of the few to engage when an appeal looked particularly tough. “Perhaps we should get Keane” was often said by the junior bar, resigned as they were to the meagre realities of the case but ever hopeful Your Honour could find a way to rescue it. It never occurred to us at the time that Your Honour might not necessarily have wanted these most difficult of appeals, but you took your instructions manfully and found challenge in the contest. And you did so in a way which inspired confidence in your team. You had that ability, characteristic of truly able leaders, to absorb the uncertainties and pressures of the cae rather than deflect them.

Your Honour was a natural force at the Bar. Not only did Your Honour posssess outstanding scholastic ability, but you had the force of personality, the skill in advocacy and the capacity for devotion to duty truly to distinguish you among your peers.

Your Honour is unpretentious and modest notwithstanding your singular talent. You have never been one overtly to seek advancement or promotion yet your appointments to the Court of Appeal and now to the Federal Court have seemed the most natural of progressions. From the perspective of those who worked with you, your advancement was always assured. That that should be so is a consequence of much more than your ability as a lawyer. Your Honour has, it has seemed to me, an acute intuition into the character and the strengths and the nuances of those around you.

No-one here who knows you can have any doubts that Your Honour will be a strong, effective and popular leader of this Court.

The Queensland Bar takes great pride in Your Honour’s appointment.

You are one of our very best.

We wish you well.

On 14 May 2010, the Federal Attorney-General released the proposed new National Regulatory System for the Legal Profession.

There is a three month consultation period.

The Association will participate in that consultation directly through the Australian Bar Association and the Law Council of Australia.

For the edification of members, reproduced below are:

- Press release by the Attorney-General

- An interview with the Attorney-General published online on 14 May 2010 by The Australian.

ATTORNEYÂ-GENERAL

HON ROBERT McCLELLAND MP

MEDIA RELEASE

14 May 2010

RELEASE OF NATIONAL LEGAL PROFESSION REFORM CONSULTATION PACKAGE

Attorney-General, Robert McClelland, today released the National Legal Profession Reform draft Bill and accompanying materials for public consultation.

The consultation package includes the draft Bill, National Rules, national conduct rules for barristers and solicitors prepared by the Australian Bar Association and the Law Council of Australia, a consultation report from the National Legal Profession Reform Taskforce, a Regulation Impact Statement, and independent economic analysis conducted by ACIL Tasman.

“Australia is now very much a national economy and for that reason we need to tackle disparate, complex systems of regulation to deliver a truly national profession,” Mr McClelland said.

The proposals contain a number of key reforms, including:

a national, co-regulatory framework with national bodies and legislation established jointly by the States and Territories with continued involvement by the profession in its regulation;

simple and uniform regulation including national practising certificates, a national register of practising entitlements, central processing of foreign lawyers’ applications for admission and registration, and all lawyers becoming officers of each State and Territory Supreme Court on admission;

reduced regulatory burdens including single national trust accounts for multijurisdictional practices and increased consistency in the regulation of legal business structures;

enhanced consumer protection through simplified processes and a National Ombudsman with greater powers to resolve clients’ disputes with their lawyers; and

support for Access to Justice initiatives, including low or no cost practising certificates for volunteer practitioners.

“The proposed Bill, comprising fewer than 200 pages, would for the first time create a single national market for legal services and a truly national legal profession with simpler uniform regulation.”

Independent economic analysis suggests that the proposed reforms will save more than $130 million over 10 years in cost and duplication and will actually grow the economy by more than $25 million.

“The proposed new national system would ensure that Governments continue to work collaboratively with the legal profession and consumers to achieve efficient and effective regulatory outcomes.”

The consultation period for the proposals will focus on maximising engagement with both the profession and consumers through the conduct of stakeholder meetings in all States and Territories, three dedicated consumer forums, telephone interviews and an online survey.

“Comments on all aspects of the proposals will be closely considered as public scrutiny and robust debate will be critical to ensuring we achieve a national system that serves us well in the coming decades.”

The Government thanks the Taskforce and Consultative Group for their work in the delivery of this package which will now be open for consultation prior to the presentation of a finalised legislative package and Inter-Governmental Agreement to COAG in the second half of this year.

The consultation package and information on how to make a submission are available at www.ag.gov.au/legalprofession. Submissions may be made until 13 August 2010.

ATTORNEY-GENERAL

HON ROBERT McCLELLAND MP

THE AUSTRALIAN ONLINE WITH CHRIS MERRITT FRIDAY, 14 MAY 2010

Subject: National Legal Profession Reform

MERRITT: Hello I’m Chris Merritt and with me is Federal Attorney General Robert McClelland, and we’re here to discuss the proposed new national regulatory system for the legal profession. Mr McClelland first up can you tell me what’s in it for law firms?

McCLELLAND: Essentially we’re about reducing the regulatory burden on the legal profession, which demonstrated by the legislation in some States will reduce from about 600 pages to about 200 pages, but it will also result in savings in the order of $16.9 million to $17.5 million for legal firms, and over a 10 year period about $132 million in savings. And there’ll also be benefits for the economy generally. But essentially, the goal is to achieve a reduction in red tape and regulatory burden faced by the profession.

MERRITT: It’s been a long time coming, it’s been decades that this has been a long sought goal. Was it very difficult to get to this point?

McCLELLAND: It was difficult. We’ve had a Taskforce working on it, and I think they’ve done an outstanding job over the last 12 months. It must be said that preliminary work was done about a decade ago, but to get everyone in the cart for the reform that occurred there it was necessary to add layers of shale on the base model. So essentially what we’ve been trying to do is peel back those layers of shale so that we have the core framework.

Ultimately, I think what has got everyone on board is that this will be truly a Federal model rather

than a Federal Government model. So essentially it will be the States and Territories in combination regulating the profession across Australia rather than the Federal Government doing so.

MERRITT: How is it going to look from the perspective of law firms, from the perspective of a national firm, what will be different?

McCLELLAND: Well, there will be one professional development framework that they’ll have to comply with, that is there will be a standard procedure, there won’t be eight different standards across the country. They will be able to maintain a single trust account in one jurisdiction rather than eight separate trust accounts. There will also be a streamlining in the focus of regulations. So we’ll be looking at broader principles rather than pedantic details, and the regulation in turn will have regard to the sophistication of their client.

MERRITT: So it sounds like there’s big benefits for law firms. What’s in it for consumers of legal services?

McCLELLAND: There will be an enhanced consumer focus. I’ve got to say some jurisdictions do that better than others, but this will be lifting the bar across the nation so that there will be consumer representation on the Board of the profession. There will also be a National Ombudsman that will have a look at costs, for instance, being fair and reasonable and looking at professional standards as well as, of course, the importance of that consumer representative on the Board of the profession influencing the development of policies and rules.

MERRITT: So that’s good for consumers, it gives them a voice in the highest counsel of the profession, but what does it do to the independence of the legal profession?

McCLELLAND: This has been the subject of quite some debate and this will be the subject of consultation. The legal profession is concerned as to the method of selection. The legal profession, including the judiciary, are concerned about the method of selection of the Board both in terms of whether it’s appointed, how it’s appointed, but also the numbers in terms of sheer voting influence. So these are issues that we’ll be discussing with them.

I’ve consistently said that I do think it is important for the legal profession to function at arms length from Government control. How we get there is going to be the subject of discussion. The Bill proposes a model whereby the standing committee of Attorneys-General appoint the Board, but we’re certainly open to other processes.

MERRITT: This sounds pretty similar to the reasonably new arrangements that are in place in England and Wales. Were you influenced by that model?

McCLELLAND: Yes to a degree. I met with the British legal profession who are pretty well down the road on their reforms, but their experience reinforces, if you like, the measures we are taking.

The measures we are taking brings the legal profession into the 21st century and importantly, from Australia’s point of view, it gives them a greater ability to launch into the rapidly emerging markets in South East Asia. British firms in particular are trying to seek a foothold here in Australia because they realise we’re on the doorstep of these rapidly emerging markets. By unifying the profession we think it will be easier for Australian lawyers to take advantage of these rapidly emerging markets. So in that sense the profession is also going to benefit.

MERRITT: What’s the next step, what’s the way ahead?

McCLELLAND: We’ve got a three month consultation period which will be beneficial. Obviously all Law Societies, Bar Associations and consumer groups will have input, as will the respective Attorneys-General and indeed the Chief Justices as leaders of the court system.

So we’re going to go around, if you like, with a roaming briefing and members of the Taskforce that developed the proposal will provide a briefing, answer questions and then we will receive the

considered submissions from the various bodies.

MERRITT: Are there any hurdles that need to be overcome?

McCLELLAND: We think the system will ultimately save money in terms of streamlining processes and enable the States and Territories to wind back some of their processes and procedures and hence costs. But initially, I think until people become confident with the system there will be a degree of replication of those central structures that we’ll need to work on over time, so at least initially there will be some duplication of costs, but again the challenge will be over time to streamline the regulation across the central system and that remaining in the States and Territories, so that we get the benefit of those savings.

MERRITT: It sounds terrific, but is it going to cost lawyers anything? Are they going to be asked to pay for it?

McCLELLAND: No, we’ve made it absolutely clear that this is all about reducing regulation and indeed cost. So the legal profession won’t be charged any additional funds for this new system and indeed ultimately we think they will be the beneficiaries, as I said at the outset, to the extent of about $16 million to $17 million a year.

MERRITT: Now when that transition to the new system takes place it looks as though those savings are going to be spread right across. There’ll be savings for the States, savings for law firms, and probably a better deal for consumers.

McCLELLAND: That is true and the challenge is to get to that point, for everyone to be convinced of good faith all round so that they’re prepared to look at where those things can be wound back. But as I’ve said, the central system is costed out at about $4 million a year which in the overall scheme of things is really quite modest given that the legal profession itself is worth about $13 billion, not million, but $13 billion a year in Australia. So, it’s an immediate challenge and one not to be sniffed at, but equally it’s not an enormous challenge given the benefits that flow.

MERRITT: Okay well that’s a great point to finish on. Thank you very much for your time. We’ve been talking to Robert McClelland, the Federal Attorney-General about the new regulatory system for the legal profession.

McCLELLAND: It’s my pleasure.

[Ends]

The Association’s Committees regularly advise and assist the Bar Council in the preparation of detailed submissions regarding draft legislation, law reform matters and current issues in the administration of justice. The expert commentaries of Bar Association Committees are sought by the Courts, the Parliament, governments as well as law reform agencies.

A list of the new Committees is below listing each Committee and the names of the relevant convenors.

Any member wishing to express an interest in being appointed to one or more of the Committees should send an email to the Chief Executive at chiefexec@qldbar.asn.au identifying the Committee on which they wish to serve and clearly setting out their contact details.

I encourage members to express an interest in participating in the Association’s work by nominating for inclusion on one of the Committee panels.

Richard Douglas S.C.

President

Standing Committees of BAQ

Committee Name

Convenor/s

C CS Ex-officio Member

Access to Justice

Long S.C.

Dollar

Administrative Law & Public Law

Hinson SC

Plunkett

Alternative Dispute Resolution

Hanger QC/DOJ North S.C.

Crow

Bar Care Implementation Committee

Bell QC

Carew

Bar Practice Course

Bain QC

Brown

Charitable Fund Raising Committee

Cameron/Kirkman-Scroope

Heaton

Collegiality Committee

Gunn/ Kate Heyworth-Smith

Plunkett

Continuing Professional Development

The Hon Justice JA Logan RFD /

The Hon Justice GC Martin/ Boddice S.C., Diehm S.C.

Davis S.C.

Commercial Law

Doyle SC/Derrington S.C.

Traves SC/Wilson

Criminal Law

Glynn SC, Devlin S.C./

Callaghan SC/ Davis S.C.

Collins/Dollar/Wilson/Courtney

Environmental Law

Keim S.C./Hay

O’Gorman S.C.

Ethics Counsellors Panel

Gotterson QC

Davis S.C.

Family Law

T. North S.C./Kent S.C.

Carew

General Litigation and Law Reform

D.J.S. Jackson QC

Brown

Human Rights and Equal Opportunities

Perkiss

Wilson

Industrial Law

Murdoch S.C.

Crow

Planning and Environment

Gallagher QC/ Gore QC

Holland

Practice and Procedure

McKenna S.C./ Charrington

Shah

Practice Structure Reform Committee

Coulsen

Amerena

Professional Conduct

Traves S.C.

Traves S.C.

Professional Indemnity/ Professional Standards Committee

Gibson QC/Carrigan

Murphy

Pupillage/ Junior

DJ Campbell S.C.

Holland

Resourcing of Justice Committee

Morris QC

Amerena

Succession

Mullins S.C.

Shah

Technology

Morris QC

Heaton

University Liaison

D O’Sullivan

Holland

Single Issues Committees of BAQ

WorkCover Inquiry

Committee

Dominic Murphy

Murphy

Valuation Legislation

Review Committee*

Grant Allan

Traves S.C.

On Friday, 19 March 2010, I witnessed the presentation of the John Koowarta Reconciliation Law Scholarship to two very impressive Indigenous law students.

The scholarship commemorates John Koowarta, a Winychanam Elder from the Archer River region in Cape York.

In presenting the scholarship, the President of the Law Council of Australia, Mr Glenn Ferguson, said that the scholarship is one small measure towards “closing the gap” between Indigenous citizens and all other Australians, and he noted that Indigenous Australians are underrepresented in the legal profession, a statistic that the Law Council of Australia is committed to addressing.

In presenting the scholarship, the President of the Law Council of Australia, Mr Glenn Ferguson, said that the scholarship is one small measure towards “closing the gap” between Indigenous citizens and all other Australians, and he noted that Indigenous Australians are underrepresented in the legal profession, a statistic that the Law Council of Australia is committed to addressing.

The scholarships have previously assisted 11 Indigenous law students to complete their legal studies and go on to admission as lawyers.

This year, Krista McMeeken of Perth and Merinda Dutton of Sydney were presented with scholarships.

Krista is in her fourth year of a Bachelor of Laws degree at the University of Western Australia. In 2007, she won the Western Australian Outstanding Female Aboriginal of the Year award and was a nominee for Western Australian Young Citizen of the Year in 2008.

Merinda is in her fourth year of a Bachelor of Jurisprudence/Bachelor of Laws degree at the University of New South Wales. She has worked as a Teaching Assistant at the Kingsford Legal Centre and as a volunteer at the UNSW Faculty of Law Indigenous Legal Centre. In 2009 she was a recipient of the Robert Riley Scholarship form the Foundation for Young Australians.

In receiving her award, Krista McMeeken stated:

“As someone who came from Esperance, WA, eight hours south of any university which taught law, and a single parent family in which I was the first to go to university, moving away to study law wasn’t easy.

Being away from home and managing the costs of university only became harder last August when I became a full time carer for my mother and therefore the sole income earner for my family, making continuing law almost financial impossible. So for me, this scholarship not only meant I could buy text books and a functioning laptop, it meant I could continue my degree at all.”

In receiving her award, Merinda Dutton stated:

“I am an Aboriginal woman and am proud of my heritage. I am 19 years old. I am the eldest of 6 children; my youngest brother is 5 years old and just started primary school. I have had to move wary from the comforts of home to begin my journey towards my law degree.

While I am loving the new Sydney lifestyle, the fast pace and my law degree, I often envy those that still live at home with their parents.

……

Previous scholarship winners such as Terri Janke who I admire and look up to for her work in Indigenous intellectual property.”

The Australian superior courts surveyed were the High Court of Australia, the State and Territory Supreme Courts and Courts of Appeal, the Federal Court of Australia, the Family Court of Australia and the Family Court of Western Australia.

The term “appearances” was defined as “those occasions in which a legal practitioner raises legal argument or adduces evidence while defending or presenting a case”, and thus did not include matters in the nature of directions hearings and mentions.

The survey findings provide comparative data about the rate of appearances of categories of barristers with the rate at which they could be expected to appear given their representation at the Bar.

EXTENT OF THE SURVEY

Most of the survey data was collected during the four week period between 4 and 29 May 2010. However, where necessary, the survey was also conducted during modified timeframes.

Most of the survey data was collected during the four week period between 4 and 29 May 2010. However, where necessary, the survey was also conducted during modified timeframes.

Nationally, the survey covered 2,320 matters involving 5,462 appearances by legal practitioners, 4,165 by males (76%) and 1,297 by females (24%). In Queensland, it covered 596 matters (that is 26% of the 2320 matters surveyed nationally) involving 1216 appearances by legal practitioners in Queensland (that is, 22% of the 5462 appearances nationally).

The survey involved a total appearance time for practitioners nationally of 15,177 hours while the total appearance time for Queensland practitioners was 1,876 hours (or 12% of the 15,177 hours nationally).

Nationally, civil matters accounted for 77% of the matters, while criminal matters accounted for 23% of the matters. In Queensland, 73% of matters surveyed were civil and 27% were criminal matters. Appearances arose from applications in 36% of the matters nationally and in 51% of the matters in Queensland. Nationally, 43% of matters were hearings while in Queensland 40% of the matters were hearings. Trials constituted 10% nationally and 4% in Queensland, and appeals constituted 12% nationally and 6% in Queensland. Nationally, 88% of matters were heard by a single judge and 12% by more than one judge, while in Queensland, these figures were 93% and 7%, respectively.

THE SURVEY POPULATION

At the time of the survey, the survey population was as follows:

Australia

Queensland

Male

Female

Male

Female

Total barristers (Australia = 5,487; Queensland = 932)

81%

19%

81%

19%

Total Silks (Australia = 827; Queensland = 94)

94%

6%

96%

4%

Total Junior Counsel (Australia = 4,660; Queensland = 838)

78%

22%

80%

20%

Silks (15% of all barristers nationally) constituted 18% of appearances while junior counsel constituted 59% of appearances. Solicitors/advocates constituted 24% of appearances of which 62% are male and 38% are female. However, it was not possible to quantify the solicitor/advocate category from any records kept and therefore no comparisons or conclusions can be made about this segment of the survey population.

MAJOR FINDINGS

Some of the more significant findings may be summarised thus:

Some of the more significant findings may be summarised thus:

- There was no significant difference between survey appearance rates and the actual Bar population of both male and female barristers;

- Nationally, the average appearance time for male barristers was 3.8 hours but only 2.8 hours for female barristers;

- In Queensland, the average appearance time for male barristers was 2.2 hours, whereas the average appearance time for female barristers was 1.5 hours; hence, average appearance time for male barristers was 46% longer than for female barristers;

- Although “other entities” (see below) brief female barristers in higher proportions than private law firms and in higher proportions than they exist in the Bar population, there is a significant gap in the length of their appearances relative to their male counterparts.

Appearances Relative To The Bar Population

Appearances relative to the bar population was as follows:

Australia

Queensland

Male

Female

Male

Female

Total barristers

81%

19%

81%

19%

Total Silks

91%

9%

95%

5%

Total Junior Counsel

78%

22%

78%

22%

Appearances By Time Duration

Appearances by time duration was as follows:

Australia

Queensland

Male

Female

Male

Female

Total barristers: per cent of hours

86%

14%

86%

14%

Total barristers: total average hours

3.8 hrs

2.8 hrs

2.2 hrs

1.5 hrs

Total Silks: total average hours

4.9 hrs

4.1 hrs

Total Junior Counsel: total average hours

3.8 hrs

2.8 hrs

Appearance by Briefing Entity

There are two categories of briefing entity, namely “private law firm”1 and “other entities”2.

Nationally:

- Private law firms briefed male barristers in 86% of matters and 87% of appearance hours while female barristers accounted for 14% of matters in 13% of appearance hours;

- Male barristers were briefed by “other entitles” in 70% of matters, whereas female barristers were briefed in 30% of matters;

- On average male barristers briefed by private law firms appear for 3.9 hours and females for 3.4 hours (a difference of 15%).

In Queensland:

- Private law firms briefed male barristers in 87% of matters and female barristers in 13% of matters;

- Male barristers were briefed by “other entitles” in 66% of matters, whereas female barristers were briefed in 34% of matters.

CONCLUSION

In my opinion, this survey confirms the need to develop strategies to increase (1) the proportion of woman at the Bar; (2) the number and quality of briefs provided to female barristers, particularly from private law firms; and (3) the advocacy role of female barristers to ensure access to silk where appearance work is more concentrated.

The Law Council is presently developing a response to the survey results.

Dan O’Gorman SC 30 April 2010

Footnotes

- includes incorporate legal practices and sole practitioners

- includes, for example, government departments and community legal services

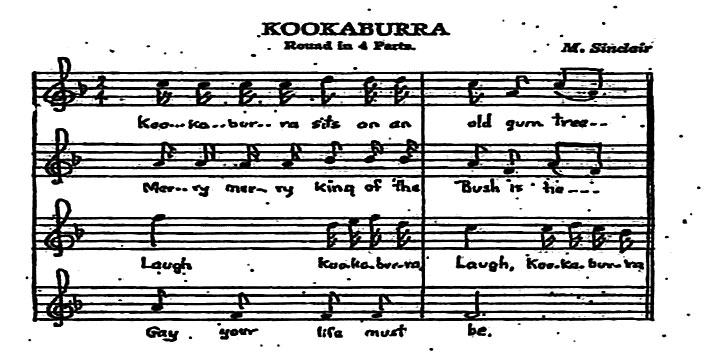

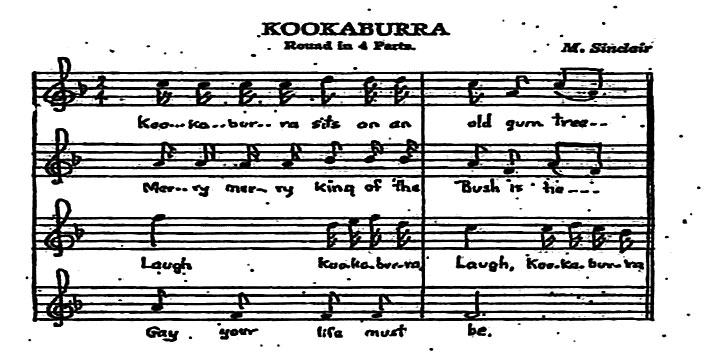

Background

Ms Marion Sinclair composed Kookaburra in 1934, and the round became the winning entry in a competition organised by the Girl Guides Association of Victoria. Ms Sinclair died in 1988 and the Public Trustee was appointed trustee of her estate. The Libraries Board claimed ownership by virtue of a donation of records made by Ms Sinclair in 1987. Larrikin claimed to have acquired the copyright in Kookaburra from the Public Trustee or the Libraries Board or both. The decision on the Order 29 questions, affirmed Larrikin’s ownership: (see Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Ltd v EMI Songs Australia Pty Limited [2009] FCA 799 (Jacobson J, 30 July 2009).

The second song, was the pop song known as Down Under, performed and recorded by the group Men at Work. Larrikin argued that the recording of Down Under made in 1981, as well as other associated works, including an early recording of the song, infringed copyright in Kookaburra. Specifically, two bars of Kookaburra were said to be reproduced in Down Under at various points through a flute riff played as follows:

- one bar (the second bar) of Kookaburra, immediately after the percussion introduction; and

- at two other points in Down Under, where the flute riff included both the first and second bar of Kookaburra

Relevantly, Kookaburra was analysed for the purpose of the proceeding as consisting of four musical bars. It should also be noted, that the flute riff contained other notes which were not part of Kookaburra.

Larrikin became aware in 2007 of the resemblance and brought its claim against the respondents. The respondents (conveniently EMI), comprised of two individuals, the composers of Down Under and former Men at Work members and two EMI corporate entities being the owner and licensee respectively of the copyright.

Issues

Leaving aside the question of causal connection which was not disputed, there were two principle issues:

- whether there was a sufficient degree of objective similarity between the flute riff in Down Under and the two bars in Kookaburra; and

- if there is such objective similarity, whether the two bars of Kookaburra were a substantial part of Kookaburra: [10] (S. W. Hart & Co Proprietary Limited v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466 at 472): see s14 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

Decision

The 1979 and 1981 recordings of Down Under infringe Larrikin’s copyright in Kookaburra because both recordings reproduce a substantial part of Kookaburra: [337]

Reasons

The parties had sought the opinions of two experts as to the differences and/or similarities between the musical compositions. The musicologist called by Larrikin, was of the opinion that there was a difference in harmony between Down Under and Kookaburra. However, those differences were overshadowed by the melody of the flute riff when it played the first two bars of Kookaburra.

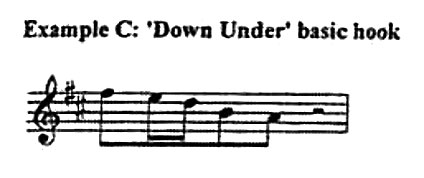

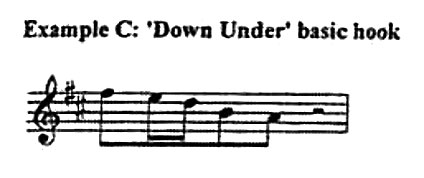

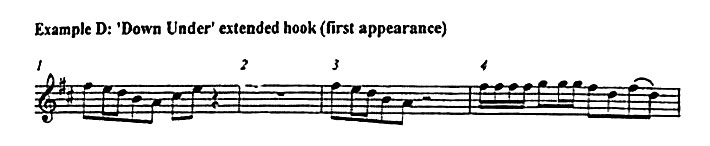

In considering these issues, the concept of musical ‘hooks’ was raised. This concept in popular music involved the introduction of a short musical instrumental infusion, which it was hoped would catch the ear of the listener, making the work memorable and recognisable, whenever the song was played. Larrikin’s evidence proceeded on the basis that those first two bars contained a musical hook. The hook, according to the Larrikin expert, appeared as follows in Down Under:

It was reproduced at [78] of his Honour’s reasons.

It was reproduced at [78] of his Honour’s reasons.

The expert called by EMI, in his affidavit evidence did not agree that the signature of Down Under was the flute riff. He opined, that the signature or hook of Down Under was the lyric ‘I come from a land down under’. However, in cross examination, he agreed that the first bar could be considered the signature of the song. The EMI expert, although acknowledging the ‘signature’ of the musical work could be the first bar, considered the argument centered around the issue of whether this bar or the first two bars, were a substantial part of Kookaburra.

Jacobson J considered the relevant decisions on the issue of substantiality and causal connection and distilled from them certain relevant principles from the issues to be determined in the case. These can be summarised:

- a sufficient degree of objective similarity is required between the two works: [33] (Francis Day & Hunter Ltd v Bron [1963] 1 Ch 587; S. W. Hart);

- there needs to be a causal connection between the conflicting works: [34] (Francis Day; S. W. Hart): [34] and that the causal connection which must be established is that the infringer copied the applicants work [49] (Francis Day on appeal)

- has the alleged infringer copied a substantial part of the copyright work: [35] (Ladbroke (Football) Ltd v William Hill (Football) Ltd [1964] 1 WLR 273);

- it is the particular form of expression which is to be protected: [40] (IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 254 ALR 386;

- the issue of substantial part is to be determined more by the quality than the quantity of what is copied: [42] (IceTV at [30], [155] and [170]);

- the causal connection which must be established is that the infringer copied the applicants work [49] (Francis Day Appeal)

- the more simple or lacking in substantial originality the copyright work, the greater will be the necessity to take a larger portion of it before a substantial part test is satisfied; [56] (IceTV)

Assessing infringement

His Honour considered that there were three steps in the comparison process. These were, firstly to identify the work in which the copyright subsists. Secondly, to identify in the allegedly infringing work, that part which is alleged to have been copied from the copyright work. Thirdly, to determine as to the part which was taken, whether that part was a substantial part of the copyright work:[60]. The copied features must therefore be a substantial part of the copyright work.

Identifying the work

The copyright work was the 1934 musical work of Miss Marion Sinclair, the successful entrant in the Guides’ competition, published by the Guides Association in their publication as “Three Rounds by Marion Sinclair” in the F key:

The offending part of Down Under

Down Under was written by Mr Hay and Mr Strykert in 1978 and recorded in 1979. The song did not originally contain the flute riff, however in the 1979 recording (where it was the B side of the record), an improvised flute solo (contributed by a Mr Ham), was added. It was Mr Hay’s evidence that he was not aware when the song was written or recorded of the reference to Kookaburra, but learned of it ‘some years ago’, but could not recall how he was made aware.

This 1979 version embodied the first four bars of Kookaburra (as they are shown above), and appeared just once in the song. A 1981 recording of Down Under appeared on the album entitled ‘Business as Usual’, an album which became a number one hit on the musical popularity charts of Australia, the UK and the USA. In this version of Down Under, the reference to Kookaburra appeared three times in various forms.

In cross examination, Mr Hay accepted that for approximately 2 or 3 years from 2002, he sometimes sang the words of Kookaburra during the song, when he performed Down Under at concerts.

The evolution of Down Under appears at [85] to [100].

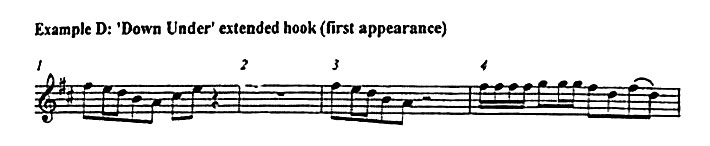

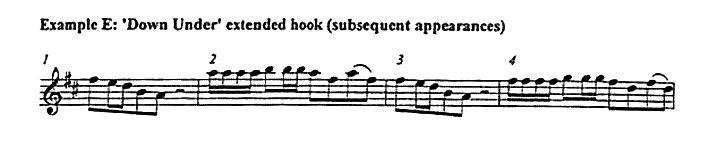

Relevantly, the expert evidence of Larrikin opined that the hook recurred throughout Down Under as both an embellishment to the accompaniment and also as one element in a longer four bar hook: [79]. The first appearance of the hook appeared as follows (in the key of D):

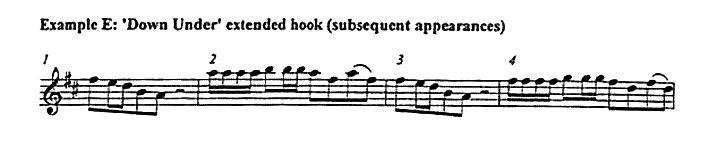

The first bar contains the basic hook with two additional notes (not appearing in Kookaburra); the second bar has music infill and the third bar contains the basic hook, while the fourth bar is the second phrase of Kookaburra. The subsequent appearances of the extended hook (also shown in the key of D) appeared as:

In this example, the first and third bars are the basic hook, while bars two and four, were opined to be direct quotes from Kookaburra. In Down Under, these phrases are played by the flute. In the opinion of the Larrikin expert, Down Under could be broken down as follows:

1 bar: Percussive intro

4 bars: Hook (Example D — 4th bar contains 2nd phrase of ‘Kookaburra’)

8 bars:Verse

8 bars: Chorus

4 bars: Hook (Example E — 2nd bar contains 1st phrase of ‘Kookaburra’, 4th bar contains 2nd phrase)

8 bars: Verse

8 bars: Chorus

8 bars: Instrumental fill

4 bars: Hook (Example E — 2nd bar contains 1st phrase of ‘Kookaburra’, 4th bar contains 2nd phrase)

8 bars: Verse

8 bars: Chorus

8 bars: Chorus

8 bars: Chorus

8 bars: Chorus (fade begins)

EMI argued that the difference in the structure of Down Under from Kookaburra, together with the differences in melody, harmony and tempo, made it difficult to recognise Kookaburra in Down Under.

Was there substantial reproduction of Kookaburra?

Jacobson J found that in both a qualitative and quantitative sense, a substantial part of Kookaburra was reproduced in Down Under, notwithstanding that the reproduction did not correspond exactly to the phrases of Kookaburra because of the Down Under structure.

His Honour’s relevant findings

His Honour’s relevant findings

His Honour accepted the conclusion of the expert for Larrikin, that the quoted passages in Down Under were the same as the melodic phrases in Kookaburra: [178]. Jacobson J also accepted the evidence of the expert for Larrikin, that the melody was tempo of Down Under was ‘more or less’ the same as one would sing Kookaburra.

The EMI expert had placed emphasis on the melodic difference between Kookaburra and Down Under. The basis of this opinion, was the harmonisation in Down Under from a major key to its relative minor key. His Honour was of the view, that the shift in harmony, did not make the Kookaburra phrases unrecogniseable: [189].

Jacobson J observed however, that whilst the EMI expert placed emphasis on the differing structures, in cross examination, he agreed with the Larrikin expert, that the call and response were a merged musical statement and that the notes from Kookaburra ‘played an important, indeed essential function’ in the flute riff.

Senior Counsel for EMI posed the question, that if Kookaburra and Down Under were both iconic Australian tunes with strong similarities, why it took so long to recognize the similarity. In this context, reference was made to the television show Spicks and Specks which exposed the similarity. His Honoue considered that the television show indicated that despite difficulties in the recognition of the connection, a ‘sensitised listener’ could make the connection: [207].

Mr Ham, who was responsible for the injection of the flute riff in Down Under, said in his affidavit, that adding the flute line was designed to add an Australian flavor. Relevantly, Mr Ham was not called. His Honour considered that not only was he entitled to infer that the witness could not have assisted EMI’s case, but that Mr Ham deliberately reproduced a part of Kookaburra as part of the concept of adding an Australian flavour: [214].

His Honour found that the reproduction by Mr Ham of the relevant bars of Kookaburra, re-inforced his Honour’s finding on objective similarity. The failure to call Mr Ham underpinned this finding. In relation to Mr Hay, his Honour accepted that the taking of portions of Kookaburra was not known to Mr Hay until much later.

Damages

Jacobson J determined that although general damages were assessable under s 115(2) of the Copyright Act 1968, there was no evidence EMI knew let alone authorized the reproduction. Although, the claim might be made against Mr Hay, it did not appear to extend to EMI.

The claim made under the Trade Practices Act, namely that income received from royalties was based upon a misrepresentation that EMI was entitled to all of the income. His Honour determined that the EMI parties had misrepresented that they were entitled to 100% of the income paid by the collecting society, through its warranty in the exclusive licence with the society and its constitution.

APRA, the collecting society for performance rights, was not in the same position, as their payments were made in accordance with member notifications not based on actual ownership.

Jacobson J pointed out at [339], that the findings did not amount to a finding that the flute riff was a substantial part of Down Under nor that it was the “hook” of that song. Accordingly, the question of the percentage of income Larrikin ought to be paid, had not been determined by this hearing, but to be determined on other principles.

Conclusion

His Honour determined that the 1979 recording and the 1981 recording of Down Under infringed Larrikin’s copyright in Kookaburra because both of those recordings reproduced a substantial part of Kookaburra.

Jacobson J also determined that Larrikin was entitled to recover damages from EMI for the infringements under the Trade Practices Act or the Fair Trading Act. Once the infringements were accepted, recovery under s 82 of the Trade Practices Act and the corresponding provisions of the Fair Trading Act followed despite the EMI defences.

Comment

In relation to the finding of substantial reproduction, his Honour made a refreshingly practical observation. With reference to the use by Mr Hay at some performances of Kookaburra when performing Down Under in around 2002, his Honour said at [228]:

The reproduction did not completely correspond to the phrases of Kookaburra because of the separation to which I have referred. But Mr Hay’s performance of the words of Kookaburra shows that a substantial part was taken. (Underline added)

Dimitrios Eliades

Footnote

- Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Ltd v EMI Songs Australia Pty Limited [2010] FCA 29 (Jacobson J, 4 February 2010)

Income Protection, Life Insurance, Trauma Insurance

QCAT commenced operations on 1 December 2009. It occupies three floors at the BOQ building 259 Queen Street, Brisbane. It is a tribunal, not a court. The distinction is one which underpins all aspects of QCAT’s development and operation. As QCAT’s progenitors, the Tribunal’s Review Independent Panel of Experts, observed1 the tribunal is not bound by the rules of evidence but must observe natural justice; representation is not as of right in most cases; and, the tribunal may adopt an inquisitorial as opposed to an adversarial approach for many types of matters — a mode of operation which recognises that many of the parties who use QCAT will be unrepresented, and will need additional assistance to ensure that they are able to use an access the Tribunal effectively.

A primary task of the President, the Panel said, will be “…to balance the competing requirements of the different QCAT jurisdictions ensuring that the tribunal has procedures and processes that generate fair outcomes but being vigilant that QCAT does not become a court”.

As the Panel also said,2 a formal, court-like approach will not assist users and is likely to impair the benefits the tribunal can deliver. At the same time, of course, QCAT needs to be flexible in the way it deals with matters, and to recognise that its procedural requirements will vary between jurisdictions.

What does QCAT do?

QCAT is a large multi-jurisdictional tribunal which makes decisions about a range of matters and, also, reviews decisions previously made by State or local government departments or regulatory authorities.

QCAT is a large multi-jurisdictional tribunal which makes decisions about a range of matters and, also, reviews decisions previously made by State or local government departments or regulatory authorities.

Its major jurisdictional areas include:

⢠Residential tenancy disputes

⢠Debt disputes

⢠Consumer disputes

⢠Minor civil disputes

⢠Other civil disputes

⢠Guardianship for adults matters

⢠Administration for adults matters

⢠Building disputes

⢠Children and young people matters

⢠Anti-discrimination matters

⢠Occupational regulation matters

⢠Retail shop lease disputes

⢠Administrative decision

QCAT absorbed 18 existing tribunals, the most well known of which were the Commercial and Consumer Tribunal, the Guardianship and Administration Tribunal, the Children’s Services Tribunal, the Anti-Discrimination Tribunal, the Legal Practitioners Tribunal and the Heath Practitioners Tribunal.

The full list is:

⢠Anti-Discrimination Tribunal

⢠Appeal Tribunal (levee banks) under the Local Government Act 1993

⢠Children Services Tribunal

⢠Commercial and Consumer Tribunal

⢠Fisheries Tribunal

⢠Guardianship and Administration Tribunal

⢠Independent Assessor under the Prostitution Act 1999

⢠Health Practitioners Tribunal

⢠Legal Practice Tribunal

⢠Misconduct Tribunal

⢠Nursing Tribunal

⢠Panel of Referees under the Fire and Rescue Service Act 1990

⢠Racing Appeals Tribunal

⢠Retail Shop Leases Tribunal

⢠Small Claims Tribunal

⢠Surveyors Disciplinary Committee

⢠Teachers Disciplinary Committee

⢠Veterinary Tribunal

QCAT also reviews a range of decisions which previously went to the Supreme, District and Magistrates Court and other statutory bodies including the Gaming Commission, and the Information Commissioner.

QCAT also reviews a range of decisions which previously went to the Supreme, District and Magistrates Court and other statutory bodies including the Gaming Commission, and the Information Commissioner.

Some of these jurisdictions were already very large, and busy. The Small Claims and Minor Debts jurisdiction, formerly in the Magistrates Court (and now called Minor Civil Disputes) has already received 4,292 new applications in the period 1 December 2009 — 31 January 2010. This is an increase of almost 50% over the same period in the Magistrates Court in 2008/2009. The increase is partly explained of course by the enlargement of the jurisdiction from $7,500 to $25,000.

The guardianship jurisdiction has, over the last 3 years, experienced annual growth in applications of between 10% and 20% but since QCAT opened its doors the increase in new matters lodged is 26%: some 1,313 applications were filed in QCAT after 1 December 2009. Plainly this is the result of the changing demographic of the Queensland population, with an increasing number of retirees, and interstate migration.

The opening of QCAT was attended by a deal of publicity, and advertisement. As a consequence other jurisdictions have also seen jumps in the numbers of new matters filed — applications relating to anti-discrimination matters are up 600%, retail shop leases by 1,600% and general administrative review matters by 83%.

More information about QCAT’s activities can be found at its website: http://www.qcat.qld.gov.au.

The Independent Panel predicted that the range of work the new tribunal might do is likely to be supplemented. Its report observed that this new large, multi-jurisdictional tribunal has a greater capacity and ability to acquire new jurisdictions than the individual, amalgamating tribunals, and is likely to be an attractive and appropriate entity to deal with merely created jurisdictions (for example, new rights of external review).3

The tribunal is created under the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal Act 2009, which sets out provisions relating to its establishment, the commencement and conduct of proceedings, the tribunal’s procedures and powers, and the appointment of members. The QCAT (Jurisdiction Provisions) Amendment Act 2009 has amended over 200 Acts giving authority to QCAT to hear particular matters. A list of all the affected legislation can be found via the QCAT website at http://www.qcat.qld.gov.au/qcat-legislation.htm. The QCAT Rules 2009 were also promulgated on 1 December last year and the QCAT Regulation 2009 commenced on 1 December 2009.4

A number of Practice Directions have also been introduced, and can be found at http://www.qcat.qld.gov.au/practice-directions.htm.

Jurisdictional structure

The tribunal operates in 3 divisions: human rights, administrative and disciplinary, and civil disputes:5

Human Rights

Civil Disputes

Administrative and Disciplinary

Anti-Discrimination

Guardianship

Clinical Research

Children’s matters

Retail Shop Leases

Building disputes

Minor civil disputes

Other civil disputes

General Administrative Review

Occupational and Business Regulation

The human rights division deals with guardianship and administration, child protection and anti-discrimination matters. The civil disputes division deals with minor civil disputes, building disputes, and retail tenancy and other civil disputes. The administrative and disciplinary division covers reviews of administrative decisions of various government departments, including local government and regulatory authorities, and disciplinary matters for a number of professions — teachers, doctors, lawyers, nurses, architects and the like.

The human rights division deals with guardianship and administration, child protection and anti-discrimination matters. The civil disputes division deals with minor civil disputes, building disputes, and retail tenancy and other civil disputes. The administrative and disciplinary division covers reviews of administrative decisions of various government departments, including local government and regulatory authorities, and disciplinary matters for a number of professions — teachers, doctors, lawyers, nurses, architects and the like.

An early policy decision has been made to avoid special lists within each division. The decision was based upon a number of factors: first, advice from other large tribunals in Victoria and Western Australia that special lists tended to create undesirable internal separation within the organisation, so that members tend to be corralled within their speciality and have little opportunity to spread their wings, as it were; secondly, a related concern that members should develop skills across a range of jurisdictions; and, thirdly, out of a desire to reduce the risk of what is known in the courts as ‘judge-shopping’ — or, the risk that members sitting constantly in one particular jurisdiction may become too set in their ways.

Appeals jurisdiction

QCAT has an internal and external appeal facility. Only a few Enabling Acts confer a right to appeal (not review) a decision by a government agency or statutory authority. Otherwise, the tribunal’s appeal jurisdiction arises out of decisions made by its members and adjudicators.

All decisions of the tribunal may be appealed, except decisions to accept or reject an application or referral under s 35.

Appeals from the following decisions must be made directly to the Court of Appeal:

⢠decisions about costs fixed or assessed under s 107; and

⢠decisions made by a judicial member of the tribunal.

The President may transfer an appeal to the Court of Appeal if it can be dealt with more effectively or conveniently by that court, and it is otherwise appropriate to do so.

Appeals against decisions made by magistrates sitting as QCAT members must be heard by judicial members of the tribunal.

Leave to appeal is required for appeals from:

⢠a decision in a proceeding for a minor civil dispute;

⢠a decision which is not the tribunal’s final decision in a proceeding; and,

⢠a costs order.

Generally, an appeal can only be brought upon a question of law. Leave to appeal is required for appeals which raise a question of fact, or a question of mixed law and fact.

Applications for leave to appeal must be made within 28 days after receiving reasons for the decision. Appeals must be lodged within 28 days of receiving reasons for the decision or, if leave is required, within 21 days after leave is given. The tribunal may extend time. The start of an appeal does not affect the operation of the decision appealed against, unless a stay is granted.

If an appeal is made on a question of law, it will only succeed if there was an error of law. The appeal tribunal may:

⢠confirm or amend the decision;

⢠set aside the decision and substitute its own;

⢠set aside the decision and return it to the tribunal for reconsideration (with or without directions, including about hearing additional evidence); and,

⢠make any other order it considers appropriate.

If an appeal is made on a question of fact or a question of mixed law and fact, the appeal is by way of rehearing and additional evidence may be heard. The appeal will only succeed if there was an error, unless fresh evidence is admitted or there has been a change in the law which the appeal tribunal takes into account. The appeal tribunal may confirm or amend the decision or set it aside and substitute its own decision.

Organisational structure

QCAT is a court of record.6 In exercising its jurisdiction, it must act independently and is not subject to the direction or control of any entity, including any Minister.7 That independence is reinforced through the appointment of a Supreme Court judge as President and a District Court judge as Deputy President and the specific provision, in s 172(5) that in performing the President’s functions, the President is not subject to direction or control by the Minister.

That said, QCAT operates within the Justice Administration Division of the Department of Justice and Attorney-General and the responsible Minister is the present Attorney-General and Minister for Industrial Relations.

QCAT is led by the President who is responsible for the overall successful operation and performance of QCAT, and the Deputy President. The President’s roles and responsibilities include QCAT’s efficient operation; overseeing the selection process for members and adjudicators; giving directions about the practices and procedures of the tribunal; and, as a member, hearing significant matters within the tribunal — in particular, matters within the former Legal Practitioners Tribunal. The Deputy President’s roles and responsibilities include assisting the President in the management of QCAT’s business, and the management of members and adjudicators and, also, hearing significant matters in the tribunal — in particular, matters formerly heard and determined in the Health Practitioners Tribunal.

QCAT is led by the President who is responsible for the overall successful operation and performance of QCAT, and the Deputy President. The President’s roles and responsibilities include QCAT’s efficient operation; overseeing the selection process for members and adjudicators; giving directions about the practices and procedures of the tribunal; and, as a member, hearing significant matters within the tribunal — in particular, matters within the former Legal Practitioners Tribunal. The Deputy President’s roles and responsibilities include assisting the President in the management of QCAT’s business, and the management of members and adjudicators and, also, hearing significant matters in the tribunal — in particular, matters formerly heard and determined in the Health Practitioners Tribunal.

Over and above the two judicial members, QCAT began operations with four Senior members, nine members and six adjudicators. The members conduct hearings and make decisions for QCAT matters; the adjudicators are primarily charged with work in the Minor Civil Disputes jurisdiction. (By arrangement with the Magistrates Court, QCAT’s adjudicators have taken over all minor civil disputes work in south-east Queensland; the balance continues to be performed by magistrates throughout the other regions of the State).

There are also about 120 sessional members, most of whom formerly had connection with one or more of the previous tribunals and “transitioned” to QCAT. They come from a variety of vocational disciplines and include a large number of lawyers.

Permanent and sessional members work together to conduct hearings (and compulsory conferences and mediations) and make decisions for QCAT matters. The size and constitution of each tribunal is a matter to be decided by the President, but never exceeds three members. Some legislation specifically provides for the size of the tribunal; otherwise, the matter is within the President’s discretion.

Judges of the Supreme and District Courts and magistrates may also be appointed as supplementary members.

The adjudicators are lawyers whose primary work is in the Minor Civil Disputes jurisdiction but they do have the power and functions of a member and may be involved in compulsory conferences, or mediation.

Administratively QCAT is supported by a Chief Executive Officer, Ms Mary Shortland, and Principal Registrar, Ms Louise Logan. Together they share about 100 registry and support staff.

QCAT’s hearing and ADR rooms are all on level 10 at 259 Queen Street.

New practices and procedures

The QCAT Act requires that the tribunal deal with matters in a way that is accessible, fair, just, economical, informal and quick: s 3(b). It must observe the rules of natural justice but is not bound by the rules of evidence or any practices or procedures applying to courts of record; and, must act with as little formality and technicality and with as much speed as the proper consideration of the matters before it permits: s 28(3). Interestingly, the Act appears to place a positive onus upon QCAT, including its tribunal members, to give such advice as is necessary to ensure that each party to a proceeding understands the Tribunal’s practices and procedures: s 29(1)(a).

Overall the tribunal must function in a way which encourages the early and economical resolution of disputes, including through ADR processes.

ADR in its various forms was already entrenched in many of the former tribunals. Some, like the Commercial and Consumer Tribunal, have long-established traditions of sending matters out to private mediators at an early stage. That strong emphasis on ADR and its importance as a vital part of the tribunal’s operations was emphasised by the Independent Panel from the time of its first report in June 2008.8

In particular, since it opened its doors QCAT has been referring a large number of matters to what the Act calls compulsory conferences — a procedure set up under Part 6. These are conferences chaired by a member of the tribunal with the primary purpose of identifying and clarifying issues in dispute; promoting settlements; identifying the questions of fact and law to be decided; if the dispute cannot be settled, making orders and giving directions about the conduct of the proceedings; and, giving directions that the member considers appropriate to resolve the dispute.

These conferences provide a private forum in which the parties can gain a better understanding of each other’s positions, and work together to explore options for resolution. Their informality and scope for open, frank communication has already produced good results in a variety of jurisdictions. They can also involve expert witnesses and, therefore, provide a forum where all matters arising in a proceeding may be explored.

The other matter strongly emphasised in QCAT is active case management. Through the use of early directions hearings, reviews and callovers, Judge Kingham and I have striven to revive a large number of dormant matters within the previous tribunals and get them moving again, towards a conclusion. The directions power contained in s 62 is sufficiently broad to allow useful directions to be given in all of the tribunals’ wide variety of jurisdictions. QCAT can give a direction at any time and do whatever is necessary for the speedy and fair conduct of the proceeding. The power enables most matters, the first time they come before QCAT, to be given sensible, case-specific directions which will advance matters towards resolution, either through ADR or an ultimate hearing.

These processes require the cooperation of the parties: under s 45 every party is obliged to act quickly in any dealing relevant to a proceeding.

When representing a party before QCAT, then, legal representatives can expect that within a short time after the application is filed they will be referred to a member for a compulsory conference, or for a review or directions hearing. Sensibly, lawyers would think in advance about ways to assist QCAT in formulating appropriate directions in their matters.

Overall, QCAT looks to lawyers to act speedily and diligently; in ways which reflect the plain, underlying philosophy of the QCAT Act; and, to develop novel and innovative ways to bring matters to a just but speedy conclusion.

Decisions

QCAT’s decisions are being published at the Supreme Court of Queensland Library website: http://www.scqld.org.au/judgments/qcat/.

The Honourable Justice Alan Wilson

Footnotes

- Tribunal’s Review Independent Panel of Experts, Final Report May 2009, p 20 para 3.8

- Ibid

- Ibid, p 24, para 4.2.4.

- The Regulation deals with procedural matters including oaths of office, prescribed fees, allowances for witnesses etc.

- QCAT r 5.

- QCAT Act 2009, s 164(1).

- Section 162.

- Tribunals Review Independent Panel of Experts Report: Stage 1, p 77, s 7.2.

Experience the difference of Bank of Queensland’s Private Bank.

Bank of Queensland’s Private Bank is designed to provide a high level of

personalised service to a select group of highly valued personal and

business customers for their banking requirements.

Here is what some of Claire’s customers have to say: “I have no hesitation in recommending Claire for any banking needs. Throughout all my dealings, Claire has demonstrated a passion for providing exceptional customer service and developing creative solutions to complex problems. Claire’s strengths are her attention to detail, taking time to understand my needs and maintaining timely communication at all times. Above all, I have the upmost trust in her experience and knowledge and know that I am getting the best possible advice and assistance available. I have no hesitation in recommending Claire to any prospective clients.” Aaron Guthrie

Senior Consultant – Global Mobility HR Support Services Boeing Australia Ltd “We found Claire to be a very outgoing, helpful and enthusiastic person in all our dealings with her at Bank of Queensland, Toowong. Her initiative in many areas allowed us to have access to systems and ideas through her regular contact. She even arranged business seminars for the local community. We feel her approach to customer service and her obvious dedication to her work makes her a stand-out in her field. It also reiterates the skill Bank of Queensland has in choosing the best people. We highly recommend Claire to anyone looking for professionalism and great service.” Doug and Sue Disher

Doug Disher Real Estate

“I find that in this day and age it is extremely rare to come across a bank manager who offers personal and tailored service in such a way that clients feel comfortable and secure. Claire, through her many years of experience does this effortlessly with an old-fashioned personal touch. She is a highly professional business woman with vast product & business knowledge. I appreciate the friendly & informative relationship that O’Neil, Scott & Associates has formed with Claire, as her assistance to our clients has become invaluable. It is for these reasons that I recommend her to you as your friendly business and personal banker.”

Kind Regards

Chris Scott

O’Neil, Scott & Associate

Legal Practice Guides and Precedents.

Share your legal knowledge with small law firms and enjoy 50% of the revenue.

For further information on writing for Smokeball click here or call 1300 292 602.

In presenting the scholarship, the President of the Law Council of Australia, Mr Glenn Ferguson, said that the scholarship is one small measure towards “closing the gap” between Indigenous citizens and all other Australians, and he noted that Indigenous Australians are underrepresented in the legal profession, a statistic that the Law Council of Australia is committed to addressing.

In presenting the scholarship, the President of the Law Council of Australia, Mr Glenn Ferguson, said that the scholarship is one small measure towards “closing the gap” between Indigenous citizens and all other Australians, and he noted that Indigenous Australians are underrepresented in the legal profession, a statistic that the Law Council of Australia is committed to addressing. Most of the survey data was collected during the four week period between 4 and 29 May 2010. However, where necessary, the survey was also conducted during modified timeframes.

Most of the survey data was collected during the four week period between 4 and 29 May 2010. However, where necessary, the survey was also conducted during modified timeframes. Some of the more significant findings may be summarised thus:

Some of the more significant findings may be summarised thus:

It was reproduced at [78] of his Honour’s reasons.

It was reproduced at [78] of his Honour’s reasons.

His Honour’s relevant findings

His Honour’s relevant findings

QCAT is a large multi-jurisdictional tribunal which makes decisions about a range of matters and, also, reviews decisions previously made by State or local government departments or regulatory authorities.

QCAT is a large multi-jurisdictional tribunal which makes decisions about a range of matters and, also, reviews decisions previously made by State or local government departments or regulatory authorities. QCAT also reviews a range of decisions which previously went to the Supreme, District and Magistrates Court and other statutory bodies including the Gaming Commission, and the Information Commissioner.

QCAT also reviews a range of decisions which previously went to the Supreme, District and Magistrates Court and other statutory bodies including the Gaming Commission, and the Information Commissioner. The human rights division deals with guardianship and administration, child protection and anti-discrimination matters. The civil disputes division deals with minor civil disputes, building disputes, and retail tenancy and other civil disputes. The administrative and disciplinary division covers reviews of administrative decisions of various government departments, including local government and regulatory authorities, and disciplinary matters for a number of professions — teachers, doctors, lawyers, nurses, architects and the like.

The human rights division deals with guardianship and administration, child protection and anti-discrimination matters. The civil disputes division deals with minor civil disputes, building disputes, and retail tenancy and other civil disputes. The administrative and disciplinary division covers reviews of administrative decisions of various government departments, including local government and regulatory authorities, and disciplinary matters for a number of professions — teachers, doctors, lawyers, nurses, architects and the like. QCAT is led by the President who is responsible for the overall successful operation and performance of QCAT, and the Deputy President. The President’s roles and responsibilities include QCAT’s efficient operation; overseeing the selection process for members and adjudicators; giving directions about the practices and procedures of the tribunal; and, as a member, hearing significant matters within the tribunal — in particular, matters within the former Legal Practitioners Tribunal. The Deputy President’s roles and responsibilities include assisting the President in the management of QCAT’s business, and the management of members and adjudicators and, also, hearing significant matters in the tribunal — in particular, matters formerly heard and determined in the Health Practitioners Tribunal.

QCAT is led by the President who is responsible for the overall successful operation and performance of QCAT, and the Deputy President. The President’s roles and responsibilities include QCAT’s efficient operation; overseeing the selection process for members and adjudicators; giving directions about the practices and procedures of the tribunal; and, as a member, hearing significant matters within the tribunal — in particular, matters within the former Legal Practitioners Tribunal. The Deputy President’s roles and responsibilities include assisting the President in the management of QCAT’s business, and the management of members and adjudicators and, also, hearing significant matters in the tribunal — in particular, matters formerly heard and determined in the Health Practitioners Tribunal.