In this paper Tony Moon looks at a number of issues which arise on a regular basis when opposing those litigants in person who stray into the area of vexatious litigation.

Discretionary Factors

Once the Court is satisfied that the threshold question is answered in the positive the Act does not prescribe what discretionary factors may or may not be relevant when considering whether an order should be made under s.6(2). However, in other jurisdictions matters such as the following have been held relevant:

- the burden of the litigation commenced by the proposed vexatious litigant upon the applicant (Granich & Associates v YAP [2004] FCA 1567 at 10); and

- whether or not the proposed vexatious litigant is likely to engage in further or ongoing litigation (Slater v The Honourable Justice Higgins [2001] FCA 549 at 35).

If the Court exercises its discretion to make an order then whilst the Court is given wide power to make such orders as it considers appropriate by s.2(c), the specific orders which are provided for in the Act are:

s.6

“….

(2) The Court may make any or all of the following ordersâ

(a) an order staying all or part of any proceeding in Queensland already instituted by the person;

(b) an order prohibiting the person from instituting proceedings, or proceedings of a particular type, in Queensland;

(c) any other order the Court considers appropriate in relation to the person. Again, “proceedings of a particular type” are defined inclusively in the Dictionary to include:

proceedings of a particular type includesâ

(a) proceedings in relation to a particular matter; and

(b) proceedings against a particular person; and

(c) proceedings in a particular court or tribunal.”

So for example, an order could be made by the Court which prevents the vexatious litigant from instituting proceedings against a particular person as opposed to preventing the vexatious litigant from instituting proceedings in general.

The Act then goes on to provide that the Court, again being the Supreme Court, may vary or set aside a vexatious proceedings order of its own volition, on application of the person the subject of the vexatious proceedings order or one of those persons named in s.5(1).

“7 Order may be varied or set aside

(1) The Court may, by order, vary or set aside a vexatious proceedings order.

(2) The Court may make the order on its own initiative or on the application ofâ

(a) the person subject to the vexatious proceedings order; or

(b) a person mentioned in section 5(1).”

It would seem pretty unlikely that any person named in s.5(1)(d) or (e) would be likely to make any such application but the Act enables them to do so.

Section 8 interestingly provides that where a vexatious proceedings order is set aside by the Court and the Court is satisfied that within 5 years of setting it aside the person has instituted or conducted a vexatious proceeding in an Australian Court or Tribunal or has acted in concert with another person who has instituted or conducted a vexatious proceeding in an Australian Court or Tribunal then the Court may reinstate the vexatious proceeding order without any fresh application under s.6 being made.

Again, the reinstatement of an order can be made upon the application of any of the persons named in s.5(1) or of the Court’s own volition.

The person against whom the Vexatious Proceedings Order is to be reinstated must be given a right to be heard before any such reinstatement order can be made (subsection 4).

Section 9 requires that any relevant order such as a vexatious proceeding order or an order setting aside or reinstating such an order must be published by the Registrar of the Court in the Gazette within 14 days of the making of the order and entered into a publicly available register kept for the purpose of the Act in the register of the Court at Brisbane within 7 days.

The Registrar of the Court may also arrange for the details to be published in another way for example of publication on the Courts website, which has been done.

Part 3 of the Act goes on to deal with the particular consequences of making a Vexatious Proceedings Order and I do not intend to deal with that in great detail in this paper save and except to note that when an order has been made whether it be prohibiting the person from instituting any proceedings or proceedings of a particular type in Queensland, then the person may not institute such proceedings without leave of the Court.

Further, another person may not, acting in concert with the person against whom the Vexatious Proceedings Order was made, institute proceedings or proceedings of the particular type within Queensland without leave.

Any proceeding which is instituted in contravention of subsection 1 is permanently stayed.

Where such proceeding is commenced in contravention of subsection 10(1) then the Court or Tribunal in which it is commenced may make an order declaring the proceeding to be a proceeding to which sub-section 10 applies and any other order in relation to the proceeding including orders as to cost. One would assume, that an order which could be made in those circumstances would be an order dismissing or striking out the proceeding.

Section 11 of the Act deals with applications for leave to institute proceedings.

The application must be made to the Court and the applicant must file an affidavit together with the application which sets out those matters required by s.11(3):

“The applicant is not permitted to serve a copy of the application or the affidavit on any person unless an order is made by the Court that the applicant do so under s.13(1)(a) when the copy must be served in accordance with the order so made”.

No doubt the reason why the application is not to be served on any other person is to prevent the vexatious litigant from again involving parties in costly legal representation simply to respond to an application under s.11.

Indeed, s.11(5) provides that the Court may dismiss the application or grant the application.

There is also a prohibition on any appeal (again trying to break that litigation chain) from any decision disposing of the application.

Section 12 provides that a Court must dismiss an application for leave where the affidavit in support is not in substantial compliance with s.11(3) or the proceeding is a vexatious proceeding.

“12 Dismissing application for leave

(1) The Court must dismiss an application made under section 11 for leave to institute a proceeding if it considersâ

(a) the affidavit does not substantially comply with section 11(3); or

(b) the proceeding is a vexatious proceeding.

(2) The application may be dismissed even if the applicant does not appear at the hearing of the application.”

Section 13 provides that before a Court can grant an application the Court must order that the applicant serve each relevant person with a copy of the application and affidavit and a notice to the persons that they are entitled to be heard on the application and give the applicant and each relevant person an opportunity to appear and be heard.

By s.13(a) the Court may grant leave to institute a particular proceeding or a proceeding of a particular type subject to conditions.

However the Court must be satisfied that the proceeding is not a vexatious proceeding before it grants leave.

The relevant persons upon whom documents are to be served and who are to be provide with a right of appearance and to be heard are set out in s.13(5).

I now turn to consider the other legislation and regulations which have bearing upon litigation or proceedings in Queensland.

Federal Court of Australia

The relevant provisions of the Federal Court of Australia are contained in the Federal Court Rules Order 21.

The Rules of the Federal Court are nowhere near as extensive or precise as the provisions of the Vexatious Proceedings Act 2005.

The Rules give the power to the Federal Court to make Vexatious Proceeding Orders. Reg 13.11 provides as follows:

“FEDERAL MAGISTRATES COURT RULES 2001 – REG 13.11

Vexatious litigants

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a person has instituted a vexatious proceeding and the Court is satisfied that the person has habitually, persistently and without reasonable grounds instituted other vexatious proceedings in the Court or any other Australian court (whether against the same person or against different persons), the Court may order:

(a) that any proceeding instituted by the person may not be continued without leave of the Court; and

(b) that the person may not institute a proceeding without leave of the Court.

(2) An order under subrule (1) may be made:

(a) on the application of a person against whom the person mentioned in subrule (1) has instituted or conducted vexatious proceedings ; or

(b) on the application of a person who has sufficient interest in the matter; or

(c) on the Court’s own motion; or

(d) on the application of the AttorneyâGeneral of the Commonwealth or of a State or Territory; or

(e) on the application of the Registrar.

(3) If a person (a vexatious litigant) habitually and persistently and without reasonable grounds institutes vexatious proceedings in the Court against another person (the person aggrieved), the Court may, on application of the person aggrieved, order:

(a) that any proceeding instituted by the vexatious litigant against the person aggrieved may not be continued without the leave of the Court; and

(b) that the vexatious litigant may not institute any proceeding against the person aggrieved without leave of the Court.

(4) A person seeking an order under this rule must file an application.

(5) The Court may rescind or vary any order made under this rule.

(6) The Court must not give a person against whom an order is made under this rule leave to institute or continue any proceeding unless the Court is satisfied that the proceeding is not an abuse of process and that there is prima facie ground for the proceeding .

(7) Unless the Court orders otherwise, an application by a person who is subject to an order under subrule (1) or (3) may be determined by the Court without an oral hearing.

Note Under section 118 of the Family Law Act, if the Court is satisfied that a family law proceeding is frivolous or vexatious, the Court may, on the application of a party, order that the person who instituted the proceeding must not, without the leave of a court having jurisdiction under that Act, institute a proceeding under that Act of the kind or kinds specified in the order.”

So by Order 21 Rule 1, the proposed vexatious litigant need not necessarily habitually and persistently and without reasonable grounds, institute proceeding against any particular person.

For the purposes of Order 21, Rule 1 the application can be made by any of the persons named in subsection (2). However, for the purposes of Order 21 Rule 2, the application may only be made by the person aggrieved.

Further, under Order 21 Rule 1 the Court may order that the Vexatious Litigant may be precluded from continuing with any proceeding instituted by that person without the leave of the Court or from instituting a proceeding without the leave of the Court.

The prohibition in that case is not directed towards any particular proceeding either on foot or to be instituted against a particular person.

In Ramsey v Skyring 164 ALR 378 at [53]-[54] Sackville J said:

“[53] In order for O 21, r 1 to apply, it must be shown that the respondent:

- habitually and persistently

- and without any reasonable cause

- institutes

- a vexatious proceeding

- in the court.

[54] It will be seen that the rule is limited to the case where the respondent institutes a proceeding in the court. In this respect it is to be contrasted, for example, with s 3 of the Vexatious Litigants Act 1981 (Qld), which allows the Supreme Court to declare a person to be a vexatious litigant if satisfied that the person has ‘frequently and without reasonable ground instituted vexatious legal proceedings’. A provision in the latter form permits the court, when considering whether the relevant criteria have been satisfied, to take into account vexatious legal proceedings instituted in courts other than the one to which the application is made (although it seems that the provision is limited to proceedings instituted in Queensland courts: O’Shea v Cameron (CA(Qld), 5 March 1996, unreported). The terms of FCR O 21, r 1 can be satisfied, however, only by proceedings instituted in this court. Even so, in determining whether particular proceedings instituted in this court are in fact ‘vexatious’, it may be appropriate to take account of proceedings in other courts where, for example, they have authoritatively resolved the particular issue against the person instituting the proceedings: cf O’Shea v Cameron, at 6, per Mackenzie J, with whom Pincus JA agreed.”

“Habitually and persistently” have been discussed in a number of cases. In Granich & Associates v Yap [2004] FCA 1567 French said:

“[8] The present application is made under O 21 r 2. The legal principles governing applications to have litigants declared vexatious under that rule were discussed by Weinberg J in Horvath v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [1999] FCA 504 at [95] to [103]. See also Ramsay v Skyring (1999) 164 ALR 378 per Sackville J, Slater v Honourable Justice Higgins [2001] FCA 549 per Madgwick J and Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Heinrich [2003] FCA 540 per Mansfield J.

[9] On any view, in my opinion, the history of Mrs Yap’s litigation in this Court against Granich & Associates, answers the criteria set out in O 21 r 2. Her repeated litigation has been vexatious in the sense that she has sought to relitigate issues which have been previously determined. It has been habitual and persistent in the senses explained by Roden J in Attorney-General v Wentworth (1988) 14 NSWLR 481 at 492 where his Honour said:

‘Habitually’ suggests that the institution of such proceedings occurs as a matter of course, or almost automatically, when the appropriate conditions (whatever they may be) exist; “persistently” suggests determination, and continuing in the face of difficulty or opposition, with a degree of stubbornness.’

The quoted observation was adopted by Sackville J in Skyring and by Mansfield in Heinrich. The want of any reasonable ground for Mrs Yap’s persistent relitigation of issues has been amply demonstrated in the judgments that have been made in the course of those proceedings.

[10] These conditions being satisfied, the Court has a discretion whether to make the order sought.”

Sackville J in Ramsey v Skyring went on to discuss the application of a number of the requirements of the Federal Court Rules as follows:

“[56] The test of whether a person ‘without any reasonable ground institutes a vexatious proceeding’ is an objective one. In Jones v Skyring (at ALJR 813), Toohey J endorsed the observation of Ormerod LJ in Re Vernazza [1960] 1 QB 197 at 208, in relation to almost identical language contained in the Supreme Court of Judicature (Consolidation) Act 1925 (UK) s 51(1):

[The words] are referring to legal proceedings, and the question is not whether they have been instituted vexatiously but whether the legal proceedings are in fact vexatious.

As Toohey J observed, the question must be decided on the facts, not by reference to whether the person against whom the order is sought has acted in good faith. It is therefore immaterial that the respondent may believe in the justice of his or her argument and may not understand that the argument has been authoritatively rejected.

[57] In Jones v Skyring, Toohey J (at ALJR 813) suggested that there was some tautology in the language of the relevant rule, since ‘vexatious’ seemed to add little to the concept of proceedings instituted ‘frequently and without reasonable ground’. His Honour was of the view that persistent attempts by a litigant to argue questions authoritatively determined against him or her were within the High Court Rules O 63, r 6(1). In Attorney-General v Wentworth, Roden J (at 492-3) considered that the test was whether an objective assessment of the proceedings instituted by the relevant person showed that they were ‘utterly hopeless’. I do not think it necessary in this case to explore whether Toohey J intended to adopt a less stringent test than that adopted by Roden J or, indeed, whether it is necessary to add anything to the language used in O 21, r 1 itself.

[58] In determining whether a person “institutes” a proceeding for the purposes of O 21, r 1, it is necessary to have regard to the definition of “proceeding” in s 4 of the Federal Court Act, since the definition applies to the FCR: Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 46(1)(a). The Federal Court Act defines ‘proceeding’ to mean:

a proceeding in a court, whether between parties or not, and includes an incidental proceeding in the course of, or in connexion with, a proceeding, and also includes an appeal.

[59] It has been accepted that the filing of an appeal involves the institution of a proceeding in the context of an application to declare a person a vexatious litigant: Vernazza (at 209-10), per Ormerod LJ; Jones v Skyring (at ALJR 813), per Toohey J. In the latter case, Toohey J (at ALJR 814) identified applications to a justice for leave to issue proceedings in consequence of a direction under the High Court Rules O 58, r 4(3) (the equivalent to FCR O 46, r 7A), notices of motion, notices of appeal and summonses as constituting the institution of legal proceedings. In Hunters Hill Municipal Council v Pedler [1976] 1 NSWLR 478, Yeldham J expressed the view (at 488) that:

where a final decision has been given, any attempt, whether by way of appeal or application to set it aside, or to set aside proceedings taken to enforce such decision, which is in substance an attempt to re-litigate what has already been decided, is the institution of legal proceedings. It is to the substance of the matter that regard must be had and not to its form”.

In my view, having regard to the definition of “proceeding” to which I have referred, the observations in these cases apply to FCR O 21, r 1.

As with the Queensland legislation once the threshold test has been satisfied then the court has a discretion as to whether or not an order should be made and if so what the terms and extent of the order will be.

In Granich & Associates v Yap (supra) French J said at [10]:

“In my opinion, the abuses perpetrated by Mrs Yap in her proceedings in this Court and the burdens unfairly thrust on Granich & Associates require that such an order should be made. I propose to order accordingly.”

Order 21 Rule 4 provides that the Court may from time to time rescind or vary any Order made under Rule 1 or 2. The lack of particularity and process by which such a recession or variation is to take place is in mark contrast to the extensive provisions in the Queensland Legislation.

Again, Order 21 Rule 5 is quite concise and to the point when providing that the Court may give leave to a person to institute or continue a proceeding who would otherwise be prevented from doing so by the order made under Rule 1 or 2 in circumstances where the Court is satisfied that the proceeding is not an abuse of process and there are prima-facie grounds for the proceeding.

Order 21 Rule 5(2) seems to attempt to provide efficient and cost effective mechanism for considering applications by persons against whom orders under Rule 1 or 2 have been made by providing that any application may be determined without an oral hearing. In such circumstances, one would assume that a Court may well be disposed to dismiss any such application on the papers without the need to involve any other parties in circumstances where it was not satisfied that the proceeding was not an abuse of process or that there were no prima-facie grounds for the proceeding.

Whilst the Rules do not seem to specifically provide a procedure to apply when the Court is considering allowing such an application, one might well assume that in most cases the Court would normally require notice of the application be given to those parties who are likely to be affected by the granting of it and that such parties would be provided an opportunity to be heard on the application. One would assume that Rules of procedural fairness would require such a course to be adopted.

It is also interesting to note, that an order made under Rule 1 or 2 will only have the effect of preventing a person from instituting or continuing a proceeding in the Federal Court. The Order has no effect upon other Courts in the Federal structure such as the Federal Magistrates Court, the Family Court or the High Court.

Federal Magistrates Court

Again the provisions dealing with vexatious litigants insofar as they are applicable to the Federal Magistrates Court are included in the Federal Magistrates Court Rules 2001 in Regulation 13.11.

Whilst the Rule is set out in a somewhat different manner, it would appear that it pretty much replicates the Federal Court Rules.

Family Court of Australia

The provisions of the Family Law Act and Rules are again different to those in both the Federal Court and the Federal Magistrates Court.

Section 118 of the Family Law Act 1975 provides as follows:

“FAMILY LAW ACT 1975 – SECT 118

Frivolous or vexatious proceedings

(1) The court may, at any stage of proceedings under this Act , if it is satisfied that the proceedings are frivolous or vexatious:

(a) dismiss the proceedings ;

(b) make such order as to costs as the court considers just; and

(c) if the court considers appropriate, on the application of a party to the proceedings –order that the person who instituted the proceedings shall not, without leave of a court having jurisdiction under this Act , institute proceedings under this Act of the kind or kinds specified in the order;

and an order made by a court under paragraph (c) has effect notwithstanding any other provision of this Act .

(2) A court may discharge or vary an order made by that court under paragraph (1)(c).”

This section gives the Family Court a wide discretion once the threshold has been established, that is that it is satisfied that the proceedings are frivolous or vexatious. It is not necessary to show that the person had acted in a manner which could be regarded as “habitual and persistent”. However, one would expect that such conduct would be of significant importance when the court considered relevant factors going to the exercise of the discretion.

The power of the Court seems to be quite a bit wider than that contained in the other provisions we have looked at above, in that it does not require any aspect of repetition or history of conduct at least in so far as the threshold test is concerned.

However, the Court is given further power to deal with such litigants by Rule 11.04 of the Family Law Rules 2004, which provides as follows:

FAMILY LAW RULES 2004 – RULE 11.04

Frivolous or vexatious case

(1) If the court is satisfied that a party has frequently started a case or appeal that is frivolous, vexatious or an abuse of process, it may:

(a) dismiss the party’s application; and

(b) order that the party may not, without the court’s permission, file or continue an application.

(2) The court may make an order under subrule (1):

(a) on its own initiative; or

(b) on the application of:

(i) a party;

(ii) for the Family Court of Australia â a Registry Manager; or

(iii) for the Family Court of a State â the Executive Officer.

(3) The court must not make an order under subrule (1) unless it has given the applicant a reasonable opportunity to be heard.

Note Under section 118 of the Act, the court may dismiss a case that is frivolous or vexatious and, on application, may prevent the person who started the case from starting a further case. Chapter 5 sets out the procedure for making an application under this rule.

Here the Court must be satisfied that the person has “frequently started a case or appeal that is frivolous, vexatious or an abuse of process”.

The difference between the words “frequently” and “habitual and persistent” should be noted. The threshold test will be easier to satisfy in the Family Court as opposed to the Federal Court and the Federal Magistrates Court.

Finally

It can be seen that the various jurisdiction have taken different approaches to the problem of vexatious litigants. The difference between them is not helpful. It is not difficult to envisage situations where a person maybe declared a vexatious litigant in one Court but not in another.

Such a situation is unsatisfactory for the parties who are the targets of the vexatious litigant and for the process of the Courts which have to deal with vexatious litigation.

I think that history shows that if a vexatious litigant is given a windows of opportunity then there is little doubt that that person will attempt to exploit the situation.

Anthony Moon

It was Marco the architect’s turn, again, to host Bloke’s Book Club and we feared the worst. The worst included having to camp under the stars in Stanthorpe in July and running up granite cliffs, the next morning, at 5.00 am. As it turned out, Marco’s genius turned benevolent and the Blokes only faced a slightly earlier start; delicious pizzas followed by Dolci Sapori sweets with lemon meringue tart and a blokey bit of team building watching the Queensland team send Locky off with a fitting series victory.

One disadvantage was that I had to suffer the cutting tongue of Marco’s wife, Maree, as she ridiculed, yet again, my efforts at bringing to the world amateur photography, sub-editor’s witty brilliance; and local sociology via my FaceBook photo albums. Still, I will take getting my arse metaphorically kicked, every time, if it comes with deliciously planned and perfectly executed pizzas in abundance.

Marco and Maree have recently returned from a holiday during which they spent several weeks in Turkey. Marco seems to have fallen very much in love with the late Kemal Ataturk. Portrait of a Turkish Family was Marco’s reading material for much of the journey and provided him with context and atmosphere for the sights he was taking in. He was keen to recommend it to the Blokes so we too could share in his new found knowledge.

Irfan Orga was born in 1908. As a result, he had no surname, Orga or otherwise, when he was born. Just as the English foisted surnames on the Welsh, thereby, creating a tribe of Williams, Davies and Joneses, Kemal Ataturk, as part of the secular republic he created, foisted surnames on the Turkish. Orga, it appears from an Afterword to Portrait, was chosen, inter alia, with the help of a pin and a map of the world.

Irfan Orga was born into a well to do family of rug merchants and exporters and lived in a beautiful house and grounds located near the water just behind the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Fate first struck when Orga was about five years old when his much loved grandfather died of a heart attack first experienced when out walking with the very young Irfan.

The family’s fortunes took further blows when war broke out and Irfan’s father and uncle were called up and left for the front, never to return. Illness struck Irfan’s widowed aunt and the family fortune was drastically diminished by a serious house fire. Shortages and poverty struck most people in Istanbul as the war dragged on and Irfan and his family faced one hardship after another.

When the war ended, Irfan and his family found their own way out of poverty but his own difficult childhood continued through the agency of military school. Eventually, Irfan found his way to officer school and a future career in the Turkish airforce. His postings took him to a number of different parts of Turkey and he achieved a level of prosperity. However, ill health and conflict within the family continued to place challenges in the way of happiness or even contentment.

Portrait was completed in England and published in 1951. The narrative leaves out much that might have been of interest in respect of the political events that brought the social changes experienced by the family. Portrait concentrates on happenings within the family. While Ataturk is mentioned both as a force for change and, at the end of his life, as a much loved figure, the reader experiences almost nothing of the struggle that brought independence for Turkey or the political decision making that followed success.

Portrait is an old fashioned book for a modern audience. It reminds me a little of other post WWII books that belonged to my parents and which I read in my own childhood.

Nonetheless, Portrait is beautifully written; easy to read; and full of interest on every page. As well as the insights I obtained concerning the dying days of the Ottomans and the early decades of the new secular Turkey, my frequent access to Wikipedia to consult the suburbs of Istanbul and the cities of Turkey mentioned in the book as I read meant that my knowledge of modern Turkey is much improved. It does indeed provide an intimate insight into the life of a family as they faced good times and bad across several decades.

The Blokes’ discussion mainly centred on Irfan’s own psychology. Several times during the book, he hints at his inability to connect emotionally with those around him. However, when his deficiencies in this regard are pointed out by his mother and grandmother, late in the text, it still seems to come as a surprise to him. He does not appear to lack empathy but the self-portrait that emerges from the pages is of someone who lacks the emotional intelligence to deal with the emotional needs of himself and others, especially, those close to him.

The Afterword is written by Ates Orga, the son of Irfan. Ates was born in 1943 but neither he nor his mother receives a mention in Portrait. Ates, mainly home taught by Irfan and now in his fifties, is an accomplished music performer, critic and producer.

The Afterword is full of revelations and insights that make it an important supplement to Portrait. We see another two decades of Irfan’s life and see him as a husband, father and writer, none of which emerged from Portrait. That is not to say that life in England between 1945 and 1970 was all beer and skittles for Irfan and his nuclear family. In an important way, however, Ates’ family portrait provides the reader with a connection between the lives we lead and those same dying days of the Ottomans which are portrayed in the opening chapters of Portrait.2

The Blokes were very happy with Marco’s choice. Opinions were mixed but even those who felt that Portrait had its flaws as literature were grateful for the addition to our reading range.

And Queensland demolished the Blues.

Stephen Keim

Footnotes

1. The motto of Eland books is “to keep the great works of travel literature in print. You can find it here.

2. For a real bringing of the eras together experience, read this Cornucopia article by Ates where he writes of his trip back to Turkey after 54 years during which he visits both sites and relatives who are covered in Portrait.

Welcome to the August edition of Hearsay. Having regard to the recent retirement of Justice Cullinane and the swearing-in of Justice North it is patently appropriate for this latest edition of Hearsay to have as its focus the Townsville Bar. Inside this edition you will find several articles authored by leading members of the Townsville Bar on a range of interesting topics of substantive law, practice and legal history. We also have the benefit of some of the speeches marking the very significant events of Justice Cullinane’s retirement and the commencement of Justice North’s judicial career. This weighty edition also features material from the sesquicentenary of the Supreme Court celebrations as well as a useful article by Dimitrios Eliades on remedies in intellectual property infringement cases and an interesting array of book reviews. Happy reading.

Geoffrey Diehm S.C.

Editor

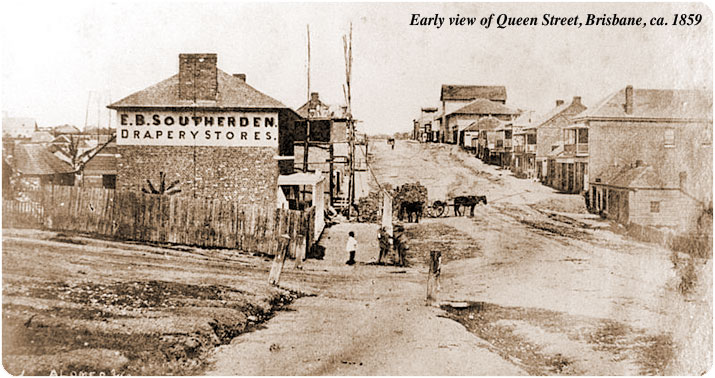

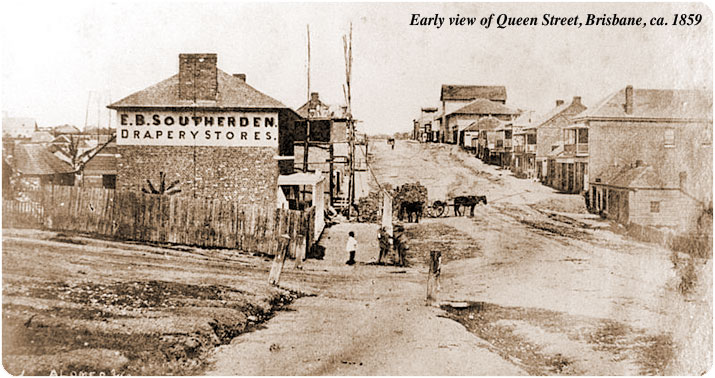

On Friday, 5 August 2011, a full complement of Supreme Court Judges, sitting en banc, many in full regalia and in the presence of Her Excellency, Ms Penelope Wensley AC, the Governor of Queensland, sat in a packed court room to celebrate the sesquicentenary of the Supreme Court of Queensland. The court, in all its splendour, was filled with retired judges, judges from other jurisdictions, magistrates, wigged and robed barristers, solicitors and members of the public. It was a momentous and significant occasion; a proud moment in our legal history.

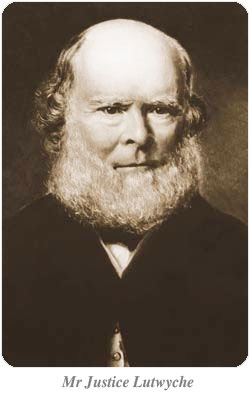

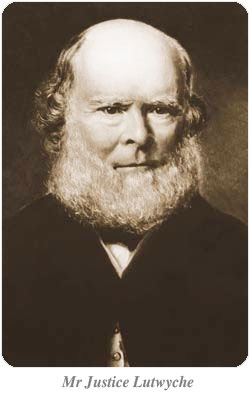

The celebrated 7 August 1861, is the date the Supreme Court Constitution Amendment Act of 1861 (“the Act”) received assent; and six days before Mr Justice Lutwyche received his commission as a Supreme Court Justice of the new colony of Queensland; the first judge of the Supreme Court. However, this is not the full story.

On 21 March 1859, and twenty months before the Act came into being, Lutwyche J received his commission as the Resident Judge of Moreton Bay. After his appointment, His Honour sat as the Supreme Court Judge in Moreton Bay, exercising both its civil and criminal jurisdictions. Nine months later, on 10 December 1859, Queensland became a separate colony when the proclamation was published in the Gazette, and read before a large and excited crowd in front of the Governor’s residence in Adelaide Street (the Deanery at St Johns). His Honour administered the oaths and over the ensuing twenty months continued to hear and determine cases in the local courts as he did before. The Act1 recognized the earlier 1859 commission and made provision for its cancellation upon His Honour receiving a new one.

On 21 March 1859, and twenty months before the Act came into being, Lutwyche J received his commission as the Resident Judge of Moreton Bay. After his appointment, His Honour sat as the Supreme Court Judge in Moreton Bay, exercising both its civil and criminal jurisdictions. Nine months later, on 10 December 1859, Queensland became a separate colony when the proclamation was published in the Gazette, and read before a large and excited crowd in front of the Governor’s residence in Adelaide Street (the Deanery at St Johns). His Honour administered the oaths and over the ensuing twenty months continued to hear and determine cases in the local courts as he did before. The Act1 recognized the earlier 1859 commission and made provision for its cancellation upon His Honour receiving a new one.

The demand for the establishment of a separate court north of the Tweed River began decades earlier, and years before a separate northern colony was established. The excessive cost and time taken to commence or defend a proceeding in Sydney resulted in regular and persistent shouts of injustice by the local residents. This argument was even raised by convicts in 1829, at a time when the penal population in Moreton Bay had reached its zenith. Moreton Bay convicts, Matthews and Allen were charged with murder and transported to Sydney for trial. They argued that prospective witnesses who could support their defence were not given permission to make the long and expensive journey south. Similar arguments again reverberated after the penal settlement closed and the locality was opened to free settlers.

The authorities responded by proclamation2 directing that a Circuit Court be held in Brisbane.3 Sitting in the old chapel at the convict barricks on 13 May 1850, Mr Justice Therry was the first Supreme Court Judge ever to preside over a trial in Brisbane. The first trial concerned a charge of larceny against William Stanley. Stanley stole a bundle of IOUs or calabashes from a hotel, located near to where QPAC is now situated at Southbank. He was convicted but in answer to a question reserved for the Full Court, it was held that these calabashes were illegal and could not be the subject of a larceny charge. During these sittings, His Honour also heard the first murder trial north of the Tweed. Jacob Wagner and Patrick Fitzgerald were charged and convicted of murdering fellow sheep-herder James Marsden at Wide Bay and hanged for their efforts. A few months later, in November 1850, Sir Alfred Stephens, the first Chief Justice ever to sit on the Supreme Court bench in Brisbane, presided over the second circuit sittings. During the sittings, His Honour tried the first ever civil case north of the Tweed River.4

The journey to Brisbane by the judges and court staff for the circuit sittings was often delayed by rough seas and inclement weather, resulting in the sittings being delayed. This inconvenience and cost to litigants reinforced the demand for a resident judge. The Sydney judges echoed this demand as they regarded the circuit court in Brisbane an arduous, dangerous and burdensome task.

The journey to Brisbane by the judges and court staff for the circuit sittings was often delayed by rough seas and inclement weather, resulting in the sittings being delayed. This inconvenience and cost to litigants reinforced the demand for a resident judge. The Sydney judges echoed this demand as they regarded the circuit court in Brisbane an arduous, dangerous and burdensome task.

The struggle to appoint a resident judge in Brisbane was a tortuous one. Superimposed on this out-cry was the growing demand for separation, the realization that it was inevitable, and the belief by many that insufficient work existed to justify the cost of a full time judge in Brisbane.

On 1 January 1856, Samuel Frederick Milford was appointed a Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales pursuant to the Moreton Bay Judge Act 1855. Despite this appointment as a resident judge, His Honour continued to travel to Brisbane for the Circuit Court sittings.

Within a short period of his appointment, the whole 1855 Act, except s 1, was repealed and replaced by the Moreton Bay Supreme Court Act 1857. This Act created the Supreme Court at Moreton Bay, to be held by a Resident Judge of Moreton Bay. In many respects this legislation established an independent and separate court in Moreton Bay. Within its territory, its jurisdiction was exclusive of the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of New South Wales with a seal similar to the seal of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. In other respects, the new court was identified with the New South Wales Supreme Court. The new Resident Judge remained for all intents and purposes a Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales; appeals lay to the Supreme Court in Sydney; and any new rules established in Brisbane were subject to review by the judges in Sydney.5

The Supreme Court of Moreton Bay was appointed to commence on 1 April 1857. Milford J returned to Brisbane and continued to sit under his existing commission until 15 April 1857 when the Supreme Court at Moreton Bay was opened and the new commissions were read. Milford J was unhappy in Brisbane, made any excuse to return to Sydney, complained of a lack of work and spent the hot summer months in the cooler south. On 20 February 1859 he resigned as the Resident Judge and was replaced by Alfred James Peter Lutwyche.

Lutwyche J was appointed as the Supreme Court Judge at Moreton Bay on 21 February 1859 and opened the court two days later.

The demand for separation succeeded. Queen Victoria signed the Letters Patent on 6 June 1859, issued under the authority of s 7 of the New South Wales Constitution Act 1855. This historical document created the new colony of Queensland and it was to take effect as soon as it was “received and published in the said colonies”. The new colony was established on 10 December 1859 with the arrival of the new Governor; when the Letters Patent were proclaimed in Queensland; and published in the Government Gazette.

The Letters Patent did not deal with the matter of a new court in Queensland but the Order in Council, also dated 6 June 1859, empowered the Governor to make laws for the administration of justice in the colony; all laws, statutes and ordinances in force in the colony of New South Wales and all the courts, civil and criminal, within the said colony and all legal commissions were said to continue.

Despite a Queensland Supreme Court not being established at that time of separation, Lutwyche J continued to preside over both civil and criminal cases in the new colony. However, at the time there was considerable debate concerning his authority.

There are arguments6 that the Supreme Court was established on 10 December 1859 and not 7 August 1861, twenty months later. His Honour Lutwyche J continued to hear and determine cases during this period and was of no doubt about his position. Further, by Article 16 and 20 all the existing courts, civil and criminal within the colony of New South Wales and all legal commissions continued to subsist in Queensland. The question of His Honour’s position was raised in R v Pugh,7 and it was ruled that His Honour held his commission from the Queen under the New South Wales Constitution Act.8 Finally, in 1863, and to remove any doubt,9 it was legislated that the Supreme Court was established at the date of separation, namely 10 December 1859.

In summary, it was right to celebrate the 7th August 2011 as the sesquicentenary of the birth of the Supreme Court of Queensland, but it must be recognized that a Supreme Court operated in Queensland from the date of proclamation.

Stephen Sheaffe10

Footnotes

- Supreme Court Constitution Amendment Act of 1861 s 3.

- Proclamation dated the 12 February 1850

- The Administration of Justice Act 1840 s 13.

- Bowerman v MvKenzie, 18 Nov, 1850; Moreton Bay Courier, 23 Nov 1850.

- BH McPherson, The History of the Supreme Court of Queensland, 1859-1960, History, Jurisdiction, Procedure, Chapter 1.

- BH McPherson, The History of the Supreme Court of Queensland, 1859-1960, History, Jurisdiction, Procedure, Chapter 2.

- (1861) SCL 3.

- Act 18 & 19 Vic 54.

- The Supreme Court Act of 1863.

- A barrister of the Supreme Court of Queensland, a former president of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland and the current president of the National Trust of Queensland.

(Photograph of Mr Justice Lutwyche Courtesy of the Supreme Court of Queensland Library.)

Lawyers are important aren’t they?:

Attorney General, Chief Magistrate, your Honours, friends.

Buoyed by the forensic skills we bring to bear and the neat arguments we are able to muster and master, and perhaps chuffed by the compliments of our peers, we lawyers tend to the view that our contribution to the community is significant.

That contribution, we champion, is integral to preservation of the rule of law.

I have no doubt that is the reality. But is that the perception of the general community (including, I hasten to add, our partners and non-legal friends)?

Not on your nelly it isn’t!

As much as it pains me to break it to you, at highest we lawyers are perceived by most of the community as a necessary evil! At lowest … well, best left unsaid.

All of you have heard the proposal for dispatching of lawyers posited by conspirator Dick the Butcher in Shakespeare’s “Henry VI”. But in that vein let me take you to more recent commentary in English literature.

In “Gulliver’s Travels”, Dean Swift was less than complimentary of the Bar as a profession. He wrote:

There is a society of men among us, bred up from their youth in the art of proving, by words multiplied for the purpose, that white is black and black is white, according as they are paid. To this society all the rest of the people are slaves.

For those your Honours who might nod ever so slightly at that characterisation, in a passage two paragraphs below that I just recited, Swift was equally disparaging of the judiciary:

The judges are persons appointed to decide all controversies of property as well as for the trial of criminals, and picked out from the most dexterous lawyers, who have grown old or lazy; and having been biased all their lives against truth and equity, lie under such a fatal necessity of favouring fraud, perjury and oppression, that I have known some of them refuse a large bribe from the side where justice lay, rather than injure the faculty, by doing anything unbecoming their nature or their office …

Perhaps Swift was an unhappy litigant at some point? I think so.

In modern legal mores, Swift’s bald cynicism towards, if not outright contempt for lawyers and the rule of law would move us characterise him as a “querelent”. Any of you who attended the annual Bar Association conference in March last year, or read the papers therefrom, would be familiar with that term.

In the same vein, apropos the judiciary, pertinent is a recent article in the Melbourne Sun Herald. In an article penned by a senior journalist by the name of Alan Howe, the following appears:

They let us down, our judiciary. When they aren’t falsely nominating their innocent dads as drivers for speeding fines, or threatening perfect strangers with their dogs faeces, or scratching others’ cars with keys … they are often going easy on the guilty…. It’s time that all our court sentences were monitored and the performance of magistrates and judges measured. It will help identify those magistrates and judges whose decisions are most successfully appealed against, and it will allow us to counsel those whose patterns of sentencing indicate a problem understanding community expectations. It might also reveal that women are more likely to go soft on crime, even unforgivable sex crimes carried out by appalling men deserving many years in jail.

This inaccurate and uninformed comment, unfortunately, is what the judiciary often confronts and must tolerate.

Politics:

None of this deleterious opinion of lawyers, bench or bar, harboured by some journalists and the public is lost on many of our politicians.

Because of this, I suspect, in substantial part, the view abroad in politics is that there are no votes in justice, as opposed to law and order.

Look no further than the deteriorating position of legal aid funding that exists in this state and nationally.

Civil legal aid funding, pervasive when I came to the Bar in 1982, no longer exists. Spec and pro bono briefing has replaced it. Lawyers are not praised for this. Rather, by the media, they are sneered at, and accused of pure self-interest.

Legal aid in criminal and family matters steadily deteriorated in federal budgetary allocation from 1997 during the Howard administration.

That sorry decline continued under the then Rudd and now Gillard administrations. The shadow Abbott government will not comment on its proposal so change of government promises nothing certain in this sphere.

The present federal contribution would need to double to be on par, in real dollars, with the 1997 funding level.

The states say they are not prepared to bridge the gap. In addition funding from interest on solicitors trust accounts is at a low level due to the Global Financial Crisis.

The aforesaid political disposition is not confined to this country. The recent experience in England, despite necessary austerity measures, evidences a similar attitude.

Legal aid funding in the United Kingdom, post-election, was slashed by about 25%.

In addition, Lord Chancellor and Justice Secretary Ken Clarke, late last year, announced the closure, over the next two years, of about 93 (out of a total of 300) Magistrates courts and 49 County courts across England and Wales. A similar approach has been adopted in Scotland with a third of local courts closed.

Think of the impact those measures will have on the local communities, and criminal and civil litigants and witnesses, together with the legal fraternity serving those communities!

On 16 June last the English Court of Appeal dismissed a judicial review application apropos a provincial court closure, albeit with the court describing as “a powerful argument” the inimical impact such closure would have on the public and the profession.

While acknowledging the large and unacceptable budgetary deficit built up by the previous UK labor government, so much for Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron’s policy of “Big Society”!

And to think English lawyers several years ago were worried about Marks & Spencer setting up a legal department next door to their bottle shop department!

Fortunately no government or alternative government in this country is suggesting such changes in a decentralized state and country such as ours. But, unfortunately, the precedent has been established.

Sense of Humour:

Just as well that, in the teeth of all this gloom, we lawyers can retain our sense of humour, and even poke a bit of fun (and occasionally a measure of bile) at each other, be we practitioners or judges.

Indeed the truthful, if not occasionally embellished rehearsal of tales of how we treat or are treated by our legal fellows is often the tonic to get us through the working week.

Let me give you a selection of some of the stories that over the years have carried me through to Friday night drinks at work or home.

Jim Douglas:

I was Justice Jim Douglas’ associate in the Supreme Court in 1979 and 1980.

In one case before Jim a litigant company director was being surgically cross-examined by one of Queensland’s then leading silks.

In response to a particular tricky question the witness, engaged in pregnant pause before he lifted his brow towards Jim, and announced with gravitas:

Your Honour, I plead the fifth amendment.

Jim turned to senior counsel for the witness and said (in Jim’s unforgettable deep baritone voice):

Mr X, should I give your client a warning so he can properly claim privilege against self-incrimination if that is apt?

Quick as a flash the witness’s silk responded:

No your Honour, let him answer. I suspect the only crime he may have committed is watching too much Perry Mason!

Counsel are known to be a little more biting with judges on occasions, especially when a judge leads with his or her chin.

A now retired Queensland Supreme Court judge, hearing a commercial trial in which an expert engineer was giving evidence on a complex issue, was struggling to understand the evidence in chief.

Gruffly this judge, in a chiding voice, said to the counsel leading evidence:

I am having real difficulty understanding this evidence Mr X. Could you please ask your question and have your witness answer in a way which, on this topic, treats me as a congenital idiot.

Quick as a flash the counsel responded:

Your Honour, neither I nor the witness will have any difficulty in abiding your Honour’s direction.

Jeff Spender and the Quiet Counsel:

It may come as a shock to some of you that judges and magistrates occasionally are rather sharp in their treatment of barristers.

As you readjust your jaws from that audacious observation, let me give you a recent example.

Some of you may have attended the farewell ceremony last year for now Jeff Spender QC, formerly Justice Spender of the Federal Court.

Jeff was a good judge and a great contributor to law and the community.

But, with respect, if he had a weakness, he tended to form early and strong views, sometimes, to use the ubiquitous cricketing metaphor, even before a ball was bowled.

A present silk was one of a number of counsel appearing before him in a matter.

Jeff, to be plain, wasn’t enamored of the merits on that barrister’s side of the record. He was anxious to ventilate his misgivings at the earliest juncture.

At any early point Jeff thundered:

For God’s sake, Mr X, would you please speak up!

The customarily softly spoken silk retorted:

I haven’t said anything yet.

Jeff, understandably, went even more rubicund than usual in his facial hue.

Grant-Taylor on Fire:

Flack from the bench is not always unwarranted.

A former District Court chairman, Judge Bill Grant-Taylor, had a penchant for interrupting counsel in the midst of submissions or witness examination. In fact I can recall appearing before him many times where he prefaced his interruption by asking the shorthand reporter not to take down the content of his following comment.

In this vein, there was one instance, which occurred relatively early in Bill’s judicial career, which is worth the telling. It was recounted to me by John Greenwood QC and Jim Crowley QC while we waited to process at last year’s legal year opening church service at St John’s Cathedral.

Bill was presiding in an old court building in mid-western Queensland (either Dalby or Roma as I recall). So old was the building and facilities that fireplaces were located at the rear of the court and also on the bench directly behind the judge. They were in use because the sittings were taking place in the dead of winter.

After a raft of early interruptions by Bill, a further attempted interruption piqued so much the counsel on his feet that he commenced to rebuke his Honour apropos the same.

Quick as a flash Bill came back:

Sorry Mr X but I think I’m on fire!

Somehow Bill’s robes had managed to get too close to the fireplace. Bill was quickly extinguished, in every sense.

Lord Russell:

If a barrister does transgress, there is often good reason for a judge or magistrate reproving him or her timeously, particularly if the barrister is a smart customer.

A good example of that is evidenced by the exchange between Lord Russell of Killowen and Mr Justice Denman. It is recounted by Lord Birkett in his very readable 1960 BBC slimline book “Six Great Advocates”.

Sir Charles Russell QC, as Lord Russell was at the Bar, was an Ulsterman of Roman Catholic stock. Interestingly he practiced mainly out of chambers in Liverpool.

Such were his qualities, including his considered bravery as an advocate, Lord Coleridge said of him:

He is the biggest advocate of the century and the ablest man in Westminster Hall.

His reputation was of not hesitating for a moment to stand up to any judge and, if the need arose, to address the judge with vehemence if he thought the rights of the advocate were invaded.

On the relevant occasion, late in the day, he addressed angry words to Mr Justice Denman for, he considered, an unnecessary intervention.

His Honour retorted that he could not trust himself to reprove Russell that night because of his sorrow and resentment at what Russell had said, but would adjourn the court and consider what to do next morning.

The next morning when the learned judge began to refer to the “painful incident” of the previous night, Russell broke in and said:

Do not say a further word, my Lord, for I have ever dismissed it from my mind.

The crowded court dissolved in laughter at Russell’s bold and utterly unexpected intervention. Even the offended judge joined in.

It is difficult to think of another advocate who would have dared to reprove the judge at night and then appear to forgive him the next morning!

That said, Peter Connolly QC springs to mind.

Judge Finn:

Some conduct of judges on the bench, however, is meant properly as pure fun.

Former Judge Vince Finn, of Townsville, used to play a prank upon newly inducted article clerks.

The clerk’s master, a party to the cabal, used to send the clerk to Vince’s chambers on a pretext.

As the clerk entered, Vince would don a sash which read “Best and Fairest” and placed on his chamber desk a large sign which read “no spitting”.

Vince would then invite the clerk to state his business.

After initial puzzlement, most of these clerks realised they joined a profession not wholly founded upon pomp and circumstance.

The fag system being what it is, a succession of clerks ran the Finn gauntlet during his Honour’s career.

Jeff Spender and his Plaques/Signs:

Judges, too, can be tough on their own.

Those of you who attended Jeff Spender’s valedictory ceremony will forgive me if I rehearse one tale, relayed to the throng quite theatrically by Michael Stewart S.C. speaking as Vice-President of the Australian Bar Association.

Jeff was the Chief Judge in Queensland and often acted as Chief Justice.

Michael spoke of a plaque which was prominently displayed on Jeff’s judicial chamber wall, readily visible to his junior judicial colleagues, whether from the Queensland or from interstate registries when he was Acting Chief Justice.

The plaque read:

The floggings will continue until morale is restored!

It says it all doesn’t it!

Jeff, a bon vivant had another sign given to him by an associate which was on his desk:

Out to lunch, but if not back by 5 pm, out to dinner too!

Conclusion:

I wish you well for the balance of your retreat.

This court has a challenging time ahead of it, in the criminal and civil spheres, with the passage of the Moynihan legislation.

The Queensland bar stands at your side in order to achieve just outcomes.

So too, I believe does the Deputy Premier and Attorney General. I thank you, Paul, for the enthusiasm and insight you have brought to your portfolio as Attorney. If together we can fix the access to justice problem that exists in this state and across the nation, our society will be better served.

Your Honours, finally, and humbly, I would remind you to be alive to the fact that occasional lapses in the bar’s performance are not always due to lack of industry on the part of the barrister concerned. Often they are a function of late or poor briefing, or occasional client impecuniosity.

Thank you for inviting me to speak to you this evening.

Cumerlong Holdings Pty Ltd v Dalcross Properties Pty Ltd [2011] HCA 27

The High Court today allowed an appeal by Cumerlong Holdings Pty Limited (“the appellant”) from a decision of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, which had upheld the decision of Smart AJ of the Supreme Court dismissing the appellant’s suit.

The High Court today allowed an appeal by Cumerlong Holdings Pty Limited (“the appellant”) from a decision of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, which had upheld the decision of Smart AJ of the Supreme Court dismissing the appellant’s suit.

The appellant had sought declaratory and injunctive relief to enforce a restrictive covenant which burdened land owned by Australasian Conference Association Ltd (“the third respondent”) for the benefit of land owned by the appellant. In resisting the suit, the third respondent and the previous owner of the burdened land (the first respondent) relied upon cl 68(2) of the Ku-ring-gai Planning Scheme Ordinance (“the Ordinance”), as amended by the Ku-ring-gai Local Environment Plan No 194 (“LEP 194”), which purported to suspend the operation of the restrictive covenant.

However, the High Court (Gummow ACJ, Hayne, Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ) held that the amendments to cl 68(2) of the Ordinance made by LEP 194 were ineffective to suspend the operation of the restrictive covenant. This was by reason of failure to comply with s 28 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW). Section 28 required that a planning instrument that had the effect of suspending the operation of a restrictive covenant, such as LEP 194 purported to do, must be approved by the Governor acting on the advice of the Executive Council. This requirement had not been complied with in making LEP 194. As a result, LEP 194 was ineffective to amend cl 68(2) of the Ordinance to effect the suspension of the restrictive covenant burdening the third respondent’s land. As a result, the High Court granted the declaratory and injunctive relief sought by the appellant.

The third respondent was ordered to pay the costs of the appellant’s appeal to the High Court.

Martin Francis Byrnes & Anor v Clifford Frank Kendle [2011] HCA 26

Today the High Court allowed an appeal from the decision of the Full Court of the Supreme Court of South Australia dismissing a claim by Mr Martin Byrnes and his mother against Mr Clifford Kendle for breach of trust in relation to the renting of a property in Murray Bridge (“the property”).

Today the High Court allowed an appeal from the decision of the Full Court of the Supreme Court of South Australia dismissing a claim by Mr Martin Byrnes and his mother against Mr Clifford Kendle for breach of trust in relation to the renting of a property in Murray Bridge (“the property”).

Mrs Joan Byrnes and Mr Kendle married in 1980 and separated in early 2007. In 1994 the property was purchased. Mr Kendle was the sole registered proprietor. In 1997 Mr Kendle executed an Acknowledgement of Trust declaring that he held a half interest in the property “upon trust” for Mrs Byrnes. In March 2007 Mrs Byrnes assigned to Mr Byrnes her interest in the property.

In December 2001 Mrs Byrnes and Mr Kendle moved out of the property. The property was let by Mr Kendle to his son, Mr Kym Kendle. Kym lived there until early 2007 but paid only two weeks’ rent. In 2008 Mr Byrnes and his mother instituted proceedings in the District Court of South Australia seeking an order for an account for Mr Kendle’s breach of trust in failing to collect rent.

The primary judge held that there was no trust because, although the deed used the words “upon trust”, evidence extrinsic to the Acknowledgement of Trust revealed that Mr Kendle nevertheless lacked the intention to create a trust. His Honour also held that, even if there had been a trust, Mr Kendle was not under a duty to rent the property and that Mrs Byrnes “co-operated” in Mr Kendle’s decision not to press for rent. On appeal, the Full Court of the Supreme Court of South Australia held that the Acknowledgement of Trust created a trust and that Mr Kendle’s subjective intentions were not relevant. However, the Full Court held that Mr Kendle did not have a duty to rent the property or collect rent and that Mrs Byrnes had consented to or acquiesced in Mr Kendle’s inaction. Mr Byrnes and his mother appealed by special leave to the High Court.

The High Court held that, by the terms of the Acknowledgement of Trust, Mr Kendle held a half interest in the property on trust for Mrs Byrnes. Evidence extrinsic to the Acknowledgement of Trust was not admissible to show that there was no intention to create a trust. The High Court also held that Mr Kendle had a duty to rent the property even without any express provision to that effect in the Acknowledgement of Trust. Mr Kendle had a continuing duty to ensure that the rent was paid and, if it were not paid, that a new tenant was found. Mr Kendle’s failure to do so was a breach of duty. He was therefore required to compensate Mrs Byrnes for her interest in the unpaid rent (less her share of the outgoings). The Court held that Mrs Byrnes’ failure to insist upon collection of the rent did not amount to consent to or acquiescence in Mr Kendle’s breach.

Green v The Queen; Quinn v The Queen [2011] HCATrans 180

On 24 June 2011, the High Court heard appeals by Shane Quinn and Brett Green against sentences imposed upon them by the Court of Criminal Appeal of New South Wales in respect of offences arising out of an enterprise involving the cultivation of cannabis plants.

On 24 June 2011, the High Court heard appeals by Shane Quinn and Brett Green against sentences imposed upon them by the Court of Criminal Appeal of New South Wales in respect of offences arising out of an enterprise involving the cultivation of cannabis plants.

Those sentences were imposed following appeals to the Court of Criminal Appeal by the New South Wales Director of Public Prosecutions (“DPP”) against the sentences imposed on Quinn and Green by the sentencing judge. The DPP did not appeal against the sentence imposed on Kodie Taylor, another participant in the enterprise. The sentencing judge had calculated the sentences imposed on Quinn and Green partly by reference to their level of involvement relative to that of Taylor, whom the same judge had sentenced two and a half months earlier. The Court of Criminal Appeal, by majority, allowed the DPP’s appeals and increased the sentences of both Quinn and Green.

Today the High Court allowed the appeals by Quinn and Green and made orders reinstating the sentences originally imposed by the sentencing judge.

The Court will publish its reasons for decision at a later date.

Maurice Blackburn Cashman v Fiona Helen Brown [2011] HCA 22

Ms Brown was a salaried partner employed by Maurice Blackburn Cashman (“MBC”) in its legal practice in Melbourne. Ms Brown alleged that between January and November 2003 she had been “systematically undermined, harassed and humiliated” by a fellow employee, despite complaints and requests for intervention made to MBC’s managing partner, and that, as a result, she had suffered injury, including psychiatric injury.

Ms Brown was a salaried partner employed by Maurice Blackburn Cashman (“MBC”) in its legal practice in Melbourne. Ms Brown alleged that between January and November 2003 she had been “systematically undermined, harassed and humiliated” by a fellow employee, despite complaints and requests for intervention made to MBC’s managing partner, and that, as a result, she had suffered injury, including psychiatric injury.

In December 2005, Ms Brown made a claim against MBC under the Accident Compensation Act 1985 (Vic) (“the Act”) for compensation for non-economic loss. The Act provided for payment of compensation “in respect of an injury resulting in permanent impairment as assessed in accordance with section 91”. Section 91 of the Act prescribed how the assessment of the degree of impairment of a worker was to be made. No compensation was payable if the degree of impairment was less than 30 per cent.

The Victorian WorkCover Authority (“the Authority”) was required under the Act to “receive and assess and accept or reject claims for compensation” and to pay “compensation to persons entitled to compensation under” the Act. In February 2006 the Authority accepted that Ms Brown had a psychological injury arising out of her employment with MBC. Ms Brown disputed the determination of her impairment made by the Authority. The Authority was therefore required by the Act to refer to a Medical Panel, established under the Act, questions relating to the degree of impairment resulting from the injury claimed by Ms Brown and whether she had an injury which was a “total loss”. In June 2006 a Medical Panel provided its opinion that there was a 30% psychiatric impairment resulting from the accepted psychological injury and that the impairment was permanent. Under the Act this was deemed to be a “serious injury” which entitled Ms Brown to bring proceedings against her employer at common law.

In 2007 Ms Brown commenced proceedings in the County Court of Victoria against MBC claiming damages for personal injuries she alleged she had suffered as a result of MBC’s negligence. MBC denied that she had suffered injury, loss and damage. Ms Brown asserted, among other things, that MBC was precluded from “making any assertion whether by pleading, submission or otherwise” and from “leading, eliciting or tendering evidence, whether in chief or in cross-examination or reexamination” that was inconsistent with the Medical Panel’s opinion that she had, as at the date of that opinion, a “serious injury” as defined in s 134AB(37)(c) of the Act, a permanent severe mental disturbance or disorder or a psychological injury arising out of her employment.

The parties asked the trial judge to reserve questions, relating to whether MBC was confined in its defence by the Medical Panel’s opinion, for the opinion of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Victoria. The Court of Appeal answered those questions adversely to MBC. MBC appealed, by special leave, to the High Court of Australia.

In the High Court the central issue was whether, as the Court of Appeal held, MBC was precluded either by the Act or by estoppel from contesting in evidence or argument in the County Court the existence and extent of Ms Brown’s injury. The High Court held that MBC was not precluded, either under the Act or as a matter of estoppel, from advancing the relevant contentions. Accordingly, the High Court allowed MBC’s appeal.

Dasreef Pty Limited v Hawchar [2011] HCA 21

Today the High Court upheld findings by the Dust Diseases Tribunal of New South Wales (“the Tribunal”) and the Court of Appeal of New South Wales that a company (Dasreef Pty Limited) was liable to pay compensation to one of its former workers (Mr Hawchar) for silicosis. The High Court found that the Court of Appeal had erred in rejecting complaints by Dasreef about the admission of opinion evidence by the Tribunal and the Tribunal’s reliance on its own experience as a “specialist tribunal”. However, the High Court held that in light of other uncontradicted evidence before the Tribunal the Court of Appeal was right to uphold the finding that Dasreef was liable to Mr Hawchar.

Today the High Court upheld findings by the Dust Diseases Tribunal of New South Wales (“the Tribunal”) and the Court of Appeal of New South Wales that a company (Dasreef Pty Limited) was liable to pay compensation to one of its former workers (Mr Hawchar) for silicosis. The High Court found that the Court of Appeal had erred in rejecting complaints by Dasreef about the admission of opinion evidence by the Tribunal and the Tribunal’s reliance on its own experience as a “specialist tribunal”. However, the High Court held that in light of other uncontradicted evidence before the Tribunal the Court of Appeal was right to uphold the finding that Dasreef was liable to Mr Hawchar.

Mr Hawchar worked for Dasreef as a labourer and stonemason over a period of around five and a half years between 1999 and 2005. He was diagnosed with early stage silicosis in 2006. He brought proceedings in the Tribunal, claiming that he had been exposed to unsafe levels of silica dust while working for Dasreef. Mr Hawchar relied on opinion evidence from Dr Kenneth Basden, a chartered chemist, chartered professional engineer and retired academic. At the time Mr Hawchar was working for Dasreef, a standard prescribing the maximum permitted exposure to respirable silica was applicable. In his report, Dr Basden spoke of an operator of an angle grinder cutting sandstone being exposed to levels of silica dust “of the order of a thousand or more times” the prescribed maximum. The Tribunal and the Court of Appeal took this evidence as expressing an opinion about the numerical or quantitative level of exposure to respirable silica encountered by Mr Hawchar, in the sense that it could form the basis of a calculation of the level of exposure.

Section 79(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) (“the Evidence Act”) provides that “[i]f a person has specialised knowledge based on the person’s training, study or experience, the opinion rule does not apply to evidence of an opinion of that person that is wholly or substantially based on that knowledge.” The “opinion rule” contained in s 76(1) of the Evidence Act provides that “[e]vidence of an opinion is not admissible to prove the existence of a fact about the existence of which the opinion was expressed.”

For a witness to give admissible evidence of an opinion about the quantitative level of Mr Hawchar’s exposure in the conditions under which he worked it would have to be shown that the witness had specialised knowledge based on their training, study or experience that permitted them to measure or estimate such a figure and that the opinion about the level of exposure was wholly or substantially based on that knowledge. In this case, Dr Basden did not give evidence asserting that his training, study or experience permitted him to provide anything beyond a “ballpark” figure estimating the amount of respirable silica dust to which a worker, when cutting stone with an angle grinder, would be exposed. The witness had seen an angle grinder used in that way only once before. He gave no evidence that he had ever measured, or sought to calculate, the amount of respirable dust to which such an operator would be exposed. The evidence was not admissible to establish the numerical or quantitative level of exposure.

Wainohu v the State of New South Wales [2011] HCA 24

The High Court today held the Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2009 (NSW) (“the Act”) invalid.

The High Court today held the Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2009 (NSW) (“the Act”) invalid.

In July 2010, the Acting Commissioner of Police for New South Wales applied to a judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales for a declaration under Part 2 of the Act in respect of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club in New South Wales (“the Club”). Under the Act, a judge who had been designated an “eligible Judge” by the Attorney-General could make a declaration in relation to an organisation. The eligible Judge had to be satisfied that the members of the organisation associated for the purposes of organising, planning, facilitating, supporting or engaging in serious criminal activity and that the organisation represented a risk to public safety and order in New South Wales. Section 13(2) of the Act provided that an eligible Judge had no obligation to provide reasons for making or refusing to make a declaration. If a declaration was made in respect of an organisation, the Supreme Court was empowered, on the application of the Commissioner of Police, to make control orders against individual members of that organisation. A person the subject of a control order was referred to in the Act as a “controlled member”. It is an offence for controlled members of an organisation to associate with one another. They are also barred from certain classes of business and certain occupations.

The plaintiff, Mr Wainohu, is a member of the Club. He applied to the High Court for a declaration that the Act was invalid on the basis that it conferred functions on the Supreme Court and its judges which undermined its institutional integrity in a way inconsistent with Ch III of the Constitution. He also argued that the Act infringed the implied constitutional freedom of political communication and political association. The parties agreed a special case which was referred to the Full Court of the High Court in October 2010.

The High Court held, by majority, that the Act was invalid. The Act provided that no reasons need be given for making a declaration. The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to make control orders was enlivened by the decision of an eligible Judge to make a declaration. Six members of the High Court held that, in those circumstances, the absence of an obligation to give reasons for the declaration after what may have been a contested application was repugnant to, or incompatible with, the institutional integrity of the Supreme Court. Because the validity of other parts of the Act relied on the validity of Part 2, the whole Act was declared invalid.

The State of New South Wales was ordered to pay Mr Wainohu’s costs.

Please direct enquiries to:

The Manager

Public Information

High Court of Australia

Parkes Place

Canberra ACT 2604

Tel: (02) 6270 6998

Fax: (02) 6270 6868

Email: enquiries@hcourt.gov.au

Website: www.hcourt.gov.au

BAQ Mediators Conference 2011

The BAQ Mediators Conference 2011 will be held at the Hyatt Regency Sanctuary Cove from 22-23 October.

Speakers at this year’s conference include:

- Ian Hanger AM QC

- The Hon Robert Fisher QC, Auckland, New Zealand

- Peta Stilgoe, Member, Queensland Civil and Administration Tribunal

- Andrew Crowe S.C.

- The Hon Justice Daubney

- Kathryn McMillan S.C

- Dr Anne Purcell, Psychologist

- Doug Murphy S.C.

- Michael Klug, Partner, Clayton Utz

- The Hon Justice May, Family Court of Australia

- Charles Brabazon QC, Retired Judge of the District Court of Queensland

- Wallace Campbell

To download the full program and registration form visit the CPD website.

CLI Series: Securities law isn’t what it used to be

Date: Thursday 1 September 2011

Time: 5.30pm — 7.00m

Venue: Banco Court, Supreme Court Complex, Brisbane

Speaker: Craig Wappett, Partner, Piper Alderman

Commentator: Professor Mike Gedye, University of Auckland

Chair: The Hon Justice P D McMurdo, Supreme Court of Queensland

Accreditation details: CLI0211, 1.5 CPD points, non allocated strand

Cross Examination of Expert Witnesses — Advocacy Training

Session 1: 7 September 2011, 5.30pm — 6.30pm

Venue: Family Court of Australia

Session 2: 21 September 2011, 5.30pm — 6.30pm

Venue: Bar Association of Queensland

Session 3: 8 October 2011, 9.30am — 2.00pm

Venue: Family Court of Australia

Accreditation details: BAQ3011, 6 CPD points, ethics and advocacy strands

Pupils Session 4: Cross Examination of expert witnesses — Rescheduled

Date: Wednesday 7 September 2011

Please note that this seminar has been rescheduled to 7 September and is one session in the Cross Examination of Expert Witnesses Advocacy Training Course.

Pupils are only required to attend the one session in the course as part of the pupillage requirements. Pupils may attend this session at no cost.

If pupils and other members wish to register for the full course and the standard registration fee will apply. Any non-pupil members that would like to attend one or all sessions are required to register with payment.

Effective Sentencing Submissions

Date: Tuesday 27 September 2011

Time: 5.30pm — 6.30pm

Venue: Bar Association Common Room

Speakers: The Hon Justice Mullins, Supreme Court of Queensland

Michael Copley S.C.

Chair: Tony Glynn S.C.

CLI Series: England as a source of Australian Law — For how long?

Date: Thursday 6 October 2011

Time: 5.30pm — 7.00pm

Venue: Banco Court, Supreme Court Complex, Brisbane

Speaker: The Hon Justice Douglas, Supreme Court of Queensland

Commentator: Professor Nick Gaskell, University of Queensland

Chair: Shane Doyle S.C.

Accreditation details: CLI0311, 1.5 CPD points, non allocated strand