In this paper Tony Moon looks at a number of issues which arise on a regular basis when opposing those litigants in person who stray into the area of vexatious litigation.

Discretionary Factors

Once the Court is satisfied that the threshold question is answered in the positive the Act does not prescribe what discretionary factors may or may not be relevant when considering whether an order should be made under s.6(2). However, in other jurisdictions matters such as the following have been held relevant:

- the burden of the litigation commenced by the proposed vexatious litigant upon the applicant (Granich & Associates v YAP [2004] FCA 1567 at 10); and

- whether or not the proposed vexatious litigant is likely to engage in further or ongoing litigation (Slater v The Honourable Justice Higgins [2001] FCA 549 at 35).

If the Court exercises its discretion to make an order then whilst the Court is given wide power to make such orders as it considers appropriate by s.2(c), the specific orders which are provided for in the Act are:

s.6

“….

(2) The Court may make any or all of the following ordersâ

(a) an order staying all or part of any proceeding in Queensland already instituted by the person;

(b) an order prohibiting the person from instituting proceedings, or proceedings of a particular type, in Queensland;

(c) any other order the Court considers appropriate in relation to the person. Again, “proceedings of a particular type” are defined inclusively in the Dictionary to include:

proceedings of a particular type includesâ

(a) proceedings in relation to a particular matter; and

(b) proceedings against a particular person; and

(c) proceedings in a particular court or tribunal.”

So for example, an order could be made by the Court which prevents the vexatious litigant from instituting proceedings against a particular person as opposed to preventing the vexatious litigant from instituting proceedings in general.

The Act then goes on to provide that the Court, again being the Supreme Court, may vary or set aside a vexatious proceedings order of its own volition, on application of the person the subject of the vexatious proceedings order or one of those persons named in s.5(1).

“7 Order may be varied or set aside

(1) The Court may, by order, vary or set aside a vexatious proceedings order.

(2) The Court may make the order on its own initiative or on the application ofâ

(a) the person subject to the vexatious proceedings order; or

(b) a person mentioned in section 5(1).”

It would seem pretty unlikely that any person named in s.5(1)(d) or (e) would be likely to make any such application but the Act enables them to do so.

Section 8 interestingly provides that where a vexatious proceedings order is set aside by the Court and the Court is satisfied that within 5 years of setting it aside the person has instituted or conducted a vexatious proceeding in an Australian Court or Tribunal or has acted in concert with another person who has instituted or conducted a vexatious proceeding in an Australian Court or Tribunal then the Court may reinstate the vexatious proceeding order without any fresh application under s.6 being made.

Again, the reinstatement of an order can be made upon the application of any of the persons named in s.5(1) or of the Court’s own volition.

The person against whom the Vexatious Proceedings Order is to be reinstated must be given a right to be heard before any such reinstatement order can be made (subsection 4).

Section 9 requires that any relevant order such as a vexatious proceeding order or an order setting aside or reinstating such an order must be published by the Registrar of the Court in the Gazette within 14 days of the making of the order and entered into a publicly available register kept for the purpose of the Act in the register of the Court at Brisbane within 7 days.

The Registrar of the Court may also arrange for the details to be published in another way for example of publication on the Courts website, which has been done.

Part 3 of the Act goes on to deal with the particular consequences of making a Vexatious Proceedings Order and I do not intend to deal with that in great detail in this paper save and except to note that when an order has been made whether it be prohibiting the person from instituting any proceedings or proceedings of a particular type in Queensland, then the person may not institute such proceedings without leave of the Court.

Further, another person may not, acting in concert with the person against whom the Vexatious Proceedings Order was made, institute proceedings or proceedings of the particular type within Queensland without leave.

Any proceeding which is instituted in contravention of subsection 1 is permanently stayed.

Where such proceeding is commenced in contravention of subsection 10(1) then the Court or Tribunal in which it is commenced may make an order declaring the proceeding to be a proceeding to which sub-section 10 applies and any other order in relation to the proceeding including orders as to cost. One would assume, that an order which could be made in those circumstances would be an order dismissing or striking out the proceeding.

Section 11 of the Act deals with applications for leave to institute proceedings.

The application must be made to the Court and the applicant must file an affidavit together with the application which sets out those matters required by s.11(3):

“The applicant is not permitted to serve a copy of the application or the affidavit on any person unless an order is made by the Court that the applicant do so under s.13(1)(a) when the copy must be served in accordance with the order so made”.

No doubt the reason why the application is not to be served on any other person is to prevent the vexatious litigant from again involving parties in costly legal representation simply to respond to an application under s.11.

Indeed, s.11(5) provides that the Court may dismiss the application or grant the application.

There is also a prohibition on any appeal (again trying to break that litigation chain) from any decision disposing of the application.

Section 12 provides that a Court must dismiss an application for leave where the affidavit in support is not in substantial compliance with s.11(3) or the proceeding is a vexatious proceeding.

“12 Dismissing application for leave

(1) The Court must dismiss an application made under section 11 for leave to institute a proceeding if it considersâ

(a) the affidavit does not substantially comply with section 11(3); or

(b) the proceeding is a vexatious proceeding.

(2) The application may be dismissed even if the applicant does not appear at the hearing of the application.”

Section 13 provides that before a Court can grant an application the Court must order that the applicant serve each relevant person with a copy of the application and affidavit and a notice to the persons that they are entitled to be heard on the application and give the applicant and each relevant person an opportunity to appear and be heard.

By s.13(a) the Court may grant leave to institute a particular proceeding or a proceeding of a particular type subject to conditions.

However the Court must be satisfied that the proceeding is not a vexatious proceeding before it grants leave.

The relevant persons upon whom documents are to be served and who are to be provide with a right of appearance and to be heard are set out in s.13(5).

I now turn to consider the other legislation and regulations which have bearing upon litigation or proceedings in Queensland.

Federal Court of Australia

The relevant provisions of the Federal Court of Australia are contained in the Federal Court Rules Order 21.

The Rules of the Federal Court are nowhere near as extensive or precise as the provisions of the Vexatious Proceedings Act 2005.

The Rules give the power to the Federal Court to make Vexatious Proceeding Orders. Reg 13.11 provides as follows:

“FEDERAL MAGISTRATES COURT RULES 2001 – REG 13.11

Vexatious litigants

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a person has instituted a vexatious proceeding and the Court is satisfied that the person has habitually, persistently and without reasonable grounds instituted other vexatious proceedings in the Court or any other Australian court (whether against the same person or against different persons), the Court may order:

(a) that any proceeding instituted by the person may not be continued without leave of the Court; and

(b) that the person may not institute a proceeding without leave of the Court.

(2) An order under subrule (1) may be made:

(a) on the application of a person against whom the person mentioned in subrule (1) has instituted or conducted vexatious proceedings ; or

(b) on the application of a person who has sufficient interest in the matter; or

(c) on the Court’s own motion; or

(d) on the application of the AttorneyâGeneral of the Commonwealth or of a State or Territory; or

(e) on the application of the Registrar.

(3) If a person (a vexatious litigant) habitually and persistently and without reasonable grounds institutes vexatious proceedings in the Court against another person (the person aggrieved), the Court may, on application of the person aggrieved, order:

(a) that any proceeding instituted by the vexatious litigant against the person aggrieved may not be continued without the leave of the Court; and

(b) that the vexatious litigant may not institute any proceeding against the person aggrieved without leave of the Court.

(4) A person seeking an order under this rule must file an application.

(5) The Court may rescind or vary any order made under this rule.

(6) The Court must not give a person against whom an order is made under this rule leave to institute or continue any proceeding unless the Court is satisfied that the proceeding is not an abuse of process and that there is prima facie ground for the proceeding .

(7) Unless the Court orders otherwise, an application by a person who is subject to an order under subrule (1) or (3) may be determined by the Court without an oral hearing.

Note Under section 118 of the Family Law Act, if the Court is satisfied that a family law proceeding is frivolous or vexatious, the Court may, on the application of a party, order that the person who instituted the proceeding must not, without the leave of a court having jurisdiction under that Act, institute a proceeding under that Act of the kind or kinds specified in the order.”

So by Order 21 Rule 1, the proposed vexatious litigant need not necessarily habitually and persistently and without reasonable grounds, institute proceeding against any particular person.

For the purposes of Order 21, Rule 1 the application can be made by any of the persons named in subsection (2). However, for the purposes of Order 21 Rule 2, the application may only be made by the person aggrieved.

Further, under Order 21 Rule 1 the Court may order that the Vexatious Litigant may be precluded from continuing with any proceeding instituted by that person without the leave of the Court or from instituting a proceeding without the leave of the Court.

The prohibition in that case is not directed towards any particular proceeding either on foot or to be instituted against a particular person.

In Ramsey v Skyring 164 ALR 378 at [53]-[54] Sackville J said:

“[53] In order for O 21, r 1 to apply, it must be shown that the respondent:

- habitually and persistently

- and without any reasonable cause

- institutes

- a vexatious proceeding

- in the court.

[54] It will be seen that the rule is limited to the case where the respondent institutes a proceeding in the court. In this respect it is to be contrasted, for example, with s 3 of the Vexatious Litigants Act 1981 (Qld), which allows the Supreme Court to declare a person to be a vexatious litigant if satisfied that the person has ‘frequently and without reasonable ground instituted vexatious legal proceedings’. A provision in the latter form permits the court, when considering whether the relevant criteria have been satisfied, to take into account vexatious legal proceedings instituted in courts other than the one to which the application is made (although it seems that the provision is limited to proceedings instituted in Queensland courts: O’Shea v Cameron (CA(Qld), 5 March 1996, unreported). The terms of FCR O 21, r 1 can be satisfied, however, only by proceedings instituted in this court. Even so, in determining whether particular proceedings instituted in this court are in fact ‘vexatious’, it may be appropriate to take account of proceedings in other courts where, for example, they have authoritatively resolved the particular issue against the person instituting the proceedings: cf O’Shea v Cameron, at 6, per Mackenzie J, with whom Pincus JA agreed.”

“Habitually and persistently” have been discussed in a number of cases. In Granich & Associates v Yap [2004] FCA 1567 French said:

“[8] The present application is made under O 21 r 2. The legal principles governing applications to have litigants declared vexatious under that rule were discussed by Weinberg J in Horvath v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [1999] FCA 504 at [95] to [103]. See also Ramsay v Skyring (1999) 164 ALR 378 per Sackville J, Slater v Honourable Justice Higgins [2001] FCA 549 per Madgwick J and Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Heinrich [2003] FCA 540 per Mansfield J.

[9] On any view, in my opinion, the history of Mrs Yap’s litigation in this Court against Granich & Associates, answers the criteria set out in O 21 r 2. Her repeated litigation has been vexatious in the sense that she has sought to relitigate issues which have been previously determined. It has been habitual and persistent in the senses explained by Roden J in Attorney-General v Wentworth (1988) 14 NSWLR 481 at 492 where his Honour said:

‘Habitually’ suggests that the institution of such proceedings occurs as a matter of course, or almost automatically, when the appropriate conditions (whatever they may be) exist; “persistently” suggests determination, and continuing in the face of difficulty or opposition, with a degree of stubbornness.’

The quoted observation was adopted by Sackville J in Skyring and by Mansfield in Heinrich. The want of any reasonable ground for Mrs Yap’s persistent relitigation of issues has been amply demonstrated in the judgments that have been made in the course of those proceedings.

[10] These conditions being satisfied, the Court has a discretion whether to make the order sought.”

Sackville J in Ramsey v Skyring went on to discuss the application of a number of the requirements of the Federal Court Rules as follows:

“[56] The test of whether a person ‘without any reasonable ground institutes a vexatious proceeding’ is an objective one. In Jones v Skyring (at ALJR 813), Toohey J endorsed the observation of Ormerod LJ in Re Vernazza [1960] 1 QB 197 at 208, in relation to almost identical language contained in the Supreme Court of Judicature (Consolidation) Act 1925 (UK) s 51(1):

[The words] are referring to legal proceedings, and the question is not whether they have been instituted vexatiously but whether the legal proceedings are in fact vexatious.

As Toohey J observed, the question must be decided on the facts, not by reference to whether the person against whom the order is sought has acted in good faith. It is therefore immaterial that the respondent may believe in the justice of his or her argument and may not understand that the argument has been authoritatively rejected.

[57] In Jones v Skyring, Toohey J (at ALJR 813) suggested that there was some tautology in the language of the relevant rule, since ‘vexatious’ seemed to add little to the concept of proceedings instituted ‘frequently and without reasonable ground’. His Honour was of the view that persistent attempts by a litigant to argue questions authoritatively determined against him or her were within the High Court Rules O 63, r 6(1). In Attorney-General v Wentworth, Roden J (at 492-3) considered that the test was whether an objective assessment of the proceedings instituted by the relevant person showed that they were ‘utterly hopeless’. I do not think it necessary in this case to explore whether Toohey J intended to adopt a less stringent test than that adopted by Roden J or, indeed, whether it is necessary to add anything to the language used in O 21, r 1 itself.

[58] In determining whether a person “institutes” a proceeding for the purposes of O 21, r 1, it is necessary to have regard to the definition of “proceeding” in s 4 of the Federal Court Act, since the definition applies to the FCR: Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 46(1)(a). The Federal Court Act defines ‘proceeding’ to mean:

a proceeding in a court, whether between parties or not, and includes an incidental proceeding in the course of, or in connexion with, a proceeding, and also includes an appeal.

[59] It has been accepted that the filing of an appeal involves the institution of a proceeding in the context of an application to declare a person a vexatious litigant: Vernazza (at 209-10), per Ormerod LJ; Jones v Skyring (at ALJR 813), per Toohey J. In the latter case, Toohey J (at ALJR 814) identified applications to a justice for leave to issue proceedings in consequence of a direction under the High Court Rules O 58, r 4(3) (the equivalent to FCR O 46, r 7A), notices of motion, notices of appeal and summonses as constituting the institution of legal proceedings. In Hunters Hill Municipal Council v Pedler [1976] 1 NSWLR 478, Yeldham J expressed the view (at 488) that:

where a final decision has been given, any attempt, whether by way of appeal or application to set it aside, or to set aside proceedings taken to enforce such decision, which is in substance an attempt to re-litigate what has already been decided, is the institution of legal proceedings. It is to the substance of the matter that regard must be had and not to its form”.

In my view, having regard to the definition of “proceeding” to which I have referred, the observations in these cases apply to FCR O 21, r 1.

As with the Queensland legislation once the threshold test has been satisfied then the court has a discretion as to whether or not an order should be made and if so what the terms and extent of the order will be.

In Granich & Associates v Yap (supra) French J said at [10]:

“In my opinion, the abuses perpetrated by Mrs Yap in her proceedings in this Court and the burdens unfairly thrust on Granich & Associates require that such an order should be made. I propose to order accordingly.”

Order 21 Rule 4 provides that the Court may from time to time rescind or vary any Order made under Rule 1 or 2. The lack of particularity and process by which such a recession or variation is to take place is in mark contrast to the extensive provisions in the Queensland Legislation.

Again, Order 21 Rule 5 is quite concise and to the point when providing that the Court may give leave to a person to institute or continue a proceeding who would otherwise be prevented from doing so by the order made under Rule 1 or 2 in circumstances where the Court is satisfied that the proceeding is not an abuse of process and there are prima-facie grounds for the proceeding.

Order 21 Rule 5(2) seems to attempt to provide efficient and cost effective mechanism for considering applications by persons against whom orders under Rule 1 or 2 have been made by providing that any application may be determined without an oral hearing. In such circumstances, one would assume that a Court may well be disposed to dismiss any such application on the papers without the need to involve any other parties in circumstances where it was not satisfied that the proceeding was not an abuse of process or that there were no prima-facie grounds for the proceeding.

Whilst the Rules do not seem to specifically provide a procedure to apply when the Court is considering allowing such an application, one might well assume that in most cases the Court would normally require notice of the application be given to those parties who are likely to be affected by the granting of it and that such parties would be provided an opportunity to be heard on the application. One would assume that Rules of procedural fairness would require such a course to be adopted.

It is also interesting to note, that an order made under Rule 1 or 2 will only have the effect of preventing a person from instituting or continuing a proceeding in the Federal Court. The Order has no effect upon other Courts in the Federal structure such as the Federal Magistrates Court, the Family Court or the High Court.

Federal Magistrates Court

Again the provisions dealing with vexatious litigants insofar as they are applicable to the Federal Magistrates Court are included in the Federal Magistrates Court Rules 2001 in Regulation 13.11.

Whilst the Rule is set out in a somewhat different manner, it would appear that it pretty much replicates the Federal Court Rules.

Family Court of Australia

The provisions of the Family Law Act and Rules are again different to those in both the Federal Court and the Federal Magistrates Court.

Section 118 of the Family Law Act 1975 provides as follows:

“FAMILY LAW ACT 1975 – SECT 118

Frivolous or vexatious proceedings

(1) The court may, at any stage of proceedings under this Act , if it is satisfied that the proceedings are frivolous or vexatious:

(a) dismiss the proceedings ;

(b) make such order as to costs as the court considers just; and

(c) if the court considers appropriate, on the application of a party to the proceedings –order that the person who instituted the proceedings shall not, without leave of a court having jurisdiction under this Act , institute proceedings under this Act of the kind or kinds specified in the order;

and an order made by a court under paragraph (c) has effect notwithstanding any other provision of this Act .

(2) A court may discharge or vary an order made by that court under paragraph (1)(c).”

This section gives the Family Court a wide discretion once the threshold has been established, that is that it is satisfied that the proceedings are frivolous or vexatious. It is not necessary to show that the person had acted in a manner which could be regarded as “habitual and persistent”. However, one would expect that such conduct would be of significant importance when the court considered relevant factors going to the exercise of the discretion.

The power of the Court seems to be quite a bit wider than that contained in the other provisions we have looked at above, in that it does not require any aspect of repetition or history of conduct at least in so far as the threshold test is concerned.

However, the Court is given further power to deal with such litigants by Rule 11.04 of the Family Law Rules 2004, which provides as follows:

FAMILY LAW RULES 2004 – RULE 11.04

Frivolous or vexatious case

(1) If the court is satisfied that a party has frequently started a case or appeal that is frivolous, vexatious or an abuse of process, it may:

(a) dismiss the party’s application; and

(b) order that the party may not, without the court’s permission, file or continue an application.

(2) The court may make an order under subrule (1):

(a) on its own initiative; or

(b) on the application of:

(i) a party;

(ii) for the Family Court of Australia â a Registry Manager; or

(iii) for the Family Court of a State â the Executive Officer.

(3) The court must not make an order under subrule (1) unless it has given the applicant a reasonable opportunity to be heard.

Note Under section 118 of the Act, the court may dismiss a case that is frivolous or vexatious and, on application, may prevent the person who started the case from starting a further case. Chapter 5 sets out the procedure for making an application under this rule.

Here the Court must be satisfied that the person has “frequently started a case or appeal that is frivolous, vexatious or an abuse of process”.

The difference between the words “frequently” and “habitual and persistent” should be noted. The threshold test will be easier to satisfy in the Family Court as opposed to the Federal Court and the Federal Magistrates Court.

Finally

It can be seen that the various jurisdiction have taken different approaches to the problem of vexatious litigants. The difference between them is not helpful. It is not difficult to envisage situations where a person maybe declared a vexatious litigant in one Court but not in another.

Such a situation is unsatisfactory for the parties who are the targets of the vexatious litigant and for the process of the Courts which have to deal with vexatious litigation.

I think that history shows that if a vexatious litigant is given a windows of opportunity then there is little doubt that that person will attempt to exploit the situation.

Anthony Moon

On Friday, 5 August 2011, a full complement of Supreme Court Judges, sitting en banc, many in full regalia and in the presence of Her Excellency, Ms Penelope Wensley AC, the Governor of Queensland, sat in a packed court room to celebrate the sesquicentenary of the Supreme Court of Queensland. The court, in all its splendour, was filled with retired judges, judges from other jurisdictions, magistrates, wigged and robed barristers, solicitors and members of the public. It was a momentous and significant occasion; a proud moment in our legal history.

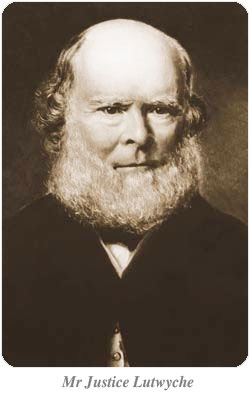

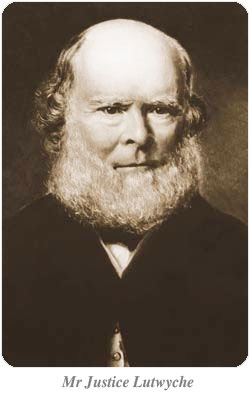

The celebrated 7 August 1861, is the date the Supreme Court Constitution Amendment Act of 1861 (“the Act”) received assent; and six days before Mr Justice Lutwyche received his commission as a Supreme Court Justice of the new colony of Queensland; the first judge of the Supreme Court. However, this is not the full story.

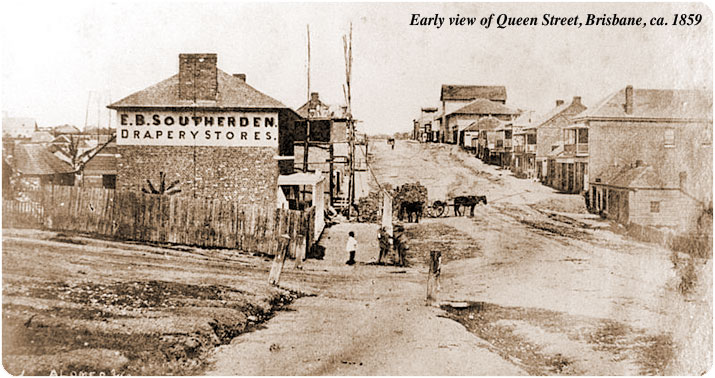

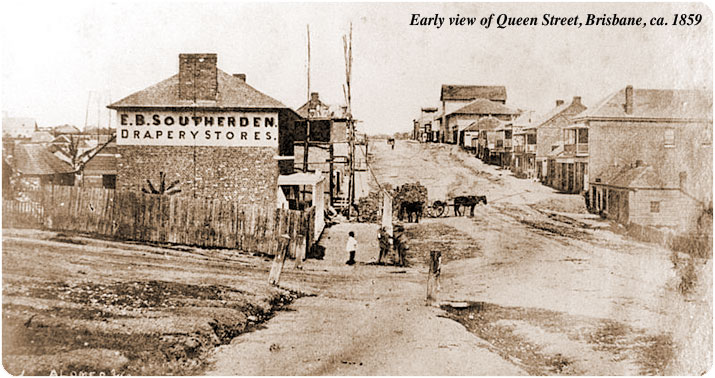

On 21 March 1859, and twenty months before the Act came into being, Lutwyche J received his commission as the Resident Judge of Moreton Bay. After his appointment, His Honour sat as the Supreme Court Judge in Moreton Bay, exercising both its civil and criminal jurisdictions. Nine months later, on 10 December 1859, Queensland became a separate colony when the proclamation was published in the Gazette, and read before a large and excited crowd in front of the Governor’s residence in Adelaide Street (the Deanery at St Johns). His Honour administered the oaths and over the ensuing twenty months continued to hear and determine cases in the local courts as he did before. The Act1 recognized the earlier 1859 commission and made provision for its cancellation upon His Honour receiving a new one.

On 21 March 1859, and twenty months before the Act came into being, Lutwyche J received his commission as the Resident Judge of Moreton Bay. After his appointment, His Honour sat as the Supreme Court Judge in Moreton Bay, exercising both its civil and criminal jurisdictions. Nine months later, on 10 December 1859, Queensland became a separate colony when the proclamation was published in the Gazette, and read before a large and excited crowd in front of the Governor’s residence in Adelaide Street (the Deanery at St Johns). His Honour administered the oaths and over the ensuing twenty months continued to hear and determine cases in the local courts as he did before. The Act1 recognized the earlier 1859 commission and made provision for its cancellation upon His Honour receiving a new one.

The demand for the establishment of a separate court north of the Tweed River began decades earlier, and years before a separate northern colony was established. The excessive cost and time taken to commence or defend a proceeding in Sydney resulted in regular and persistent shouts of injustice by the local residents. This argument was even raised by convicts in 1829, at a time when the penal population in Moreton Bay had reached its zenith. Moreton Bay convicts, Matthews and Allen were charged with murder and transported to Sydney for trial. They argued that prospective witnesses who could support their defence were not given permission to make the long and expensive journey south. Similar arguments again reverberated after the penal settlement closed and the locality was opened to free settlers.

The authorities responded by proclamation2 directing that a Circuit Court be held in Brisbane.3 Sitting in the old chapel at the convict barricks on 13 May 1850, Mr Justice Therry was the first Supreme Court Judge ever to preside over a trial in Brisbane. The first trial concerned a charge of larceny against William Stanley. Stanley stole a bundle of IOUs or calabashes from a hotel, located near to where QPAC is now situated at Southbank. He was convicted but in answer to a question reserved for the Full Court, it was held that these calabashes were illegal and could not be the subject of a larceny charge. During these sittings, His Honour also heard the first murder trial north of the Tweed. Jacob Wagner and Patrick Fitzgerald were charged and convicted of murdering fellow sheep-herder James Marsden at Wide Bay and hanged for their efforts. A few months later, in November 1850, Sir Alfred Stephens, the first Chief Justice ever to sit on the Supreme Court bench in Brisbane, presided over the second circuit sittings. During the sittings, His Honour tried the first ever civil case north of the Tweed River.4

The journey to Brisbane by the judges and court staff for the circuit sittings was often delayed by rough seas and inclement weather, resulting in the sittings being delayed. This inconvenience and cost to litigants reinforced the demand for a resident judge. The Sydney judges echoed this demand as they regarded the circuit court in Brisbane an arduous, dangerous and burdensome task.

The journey to Brisbane by the judges and court staff for the circuit sittings was often delayed by rough seas and inclement weather, resulting in the sittings being delayed. This inconvenience and cost to litigants reinforced the demand for a resident judge. The Sydney judges echoed this demand as they regarded the circuit court in Brisbane an arduous, dangerous and burdensome task.

The struggle to appoint a resident judge in Brisbane was a tortuous one. Superimposed on this out-cry was the growing demand for separation, the realization that it was inevitable, and the belief by many that insufficient work existed to justify the cost of a full time judge in Brisbane.

On 1 January 1856, Samuel Frederick Milford was appointed a Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales pursuant to the Moreton Bay Judge Act 1855. Despite this appointment as a resident judge, His Honour continued to travel to Brisbane for the Circuit Court sittings.

Within a short period of his appointment, the whole 1855 Act, except s 1, was repealed and replaced by the Moreton Bay Supreme Court Act 1857. This Act created the Supreme Court at Moreton Bay, to be held by a Resident Judge of Moreton Bay. In many respects this legislation established an independent and separate court in Moreton Bay. Within its territory, its jurisdiction was exclusive of the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of New South Wales with a seal similar to the seal of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. In other respects, the new court was identified with the New South Wales Supreme Court. The new Resident Judge remained for all intents and purposes a Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales; appeals lay to the Supreme Court in Sydney; and any new rules established in Brisbane were subject to review by the judges in Sydney.5

The Supreme Court of Moreton Bay was appointed to commence on 1 April 1857. Milford J returned to Brisbane and continued to sit under his existing commission until 15 April 1857 when the Supreme Court at Moreton Bay was opened and the new commissions were read. Milford J was unhappy in Brisbane, made any excuse to return to Sydney, complained of a lack of work and spent the hot summer months in the cooler south. On 20 February 1859 he resigned as the Resident Judge and was replaced by Alfred James Peter Lutwyche.

Lutwyche J was appointed as the Supreme Court Judge at Moreton Bay on 21 February 1859 and opened the court two days later.

The demand for separation succeeded. Queen Victoria signed the Letters Patent on 6 June 1859, issued under the authority of s 7 of the New South Wales Constitution Act 1855. This historical document created the new colony of Queensland and it was to take effect as soon as it was “received and published in the said colonies”. The new colony was established on 10 December 1859 with the arrival of the new Governor; when the Letters Patent were proclaimed in Queensland; and published in the Government Gazette.

The Letters Patent did not deal with the matter of a new court in Queensland but the Order in Council, also dated 6 June 1859, empowered the Governor to make laws for the administration of justice in the colony; all laws, statutes and ordinances in force in the colony of New South Wales and all the courts, civil and criminal, within the said colony and all legal commissions were said to continue.

Despite a Queensland Supreme Court not being established at that time of separation, Lutwyche J continued to preside over both civil and criminal cases in the new colony. However, at the time there was considerable debate concerning his authority.

There are arguments6 that the Supreme Court was established on 10 December 1859 and not 7 August 1861, twenty months later. His Honour Lutwyche J continued to hear and determine cases during this period and was of no doubt about his position. Further, by Article 16 and 20 all the existing courts, civil and criminal within the colony of New South Wales and all legal commissions continued to subsist in Queensland. The question of His Honour’s position was raised in R v Pugh,7 and it was ruled that His Honour held his commission from the Queen under the New South Wales Constitution Act.8 Finally, in 1863, and to remove any doubt,9 it was legislated that the Supreme Court was established at the date of separation, namely 10 December 1859.

In summary, it was right to celebrate the 7th August 2011 as the sesquicentenary of the birth of the Supreme Court of Queensland, but it must be recognized that a Supreme Court operated in Queensland from the date of proclamation.

Stephen Sheaffe10

Footnotes

- Supreme Court Constitution Amendment Act of 1861 s 3.

- Proclamation dated the 12 February 1850

- The Administration of Justice Act 1840 s 13.

- Bowerman v MvKenzie, 18 Nov, 1850; Moreton Bay Courier, 23 Nov 1850.

- BH McPherson, The History of the Supreme Court of Queensland, 1859-1960, History, Jurisdiction, Procedure, Chapter 1.

- BH McPherson, The History of the Supreme Court of Queensland, 1859-1960, History, Jurisdiction, Procedure, Chapter 2.

- (1861) SCL 3.

- Act 18 & 19 Vic 54.

- The Supreme Court Act of 1863.

- A barrister of the Supreme Court of Queensland, a former president of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland and the current president of the National Trust of Queensland.

(Photograph of Mr Justice Lutwyche Courtesy of the Supreme Court of Queensland Library.)

Mark Standen

NSW Law Enforcement is in shock after the assistant director of the State Crime Commission, Mark Standen, was found guilty of conspiring to import drugs and pervert the course of justice.

Listen

Frank Cassar: Australia’s worst landlord?

Melbourne landlord Frank Cassar has a string of unpaid court orders. He and his wife have just been told by the Supreme Court: stop dealing with tenants and hire a real estate agent.

Listen

Canberra v Big Tobacco

Canberra and Big Tobacco are at war over plain packaging of cigarettes.

There’s a Freedom of Information battle raging in the Federal Court, a dispute over rights spelled out in the HK-Australia Business Investment Treaty and a likely constitutional challenge – it centres on whether or not Canberra is taking away intellectual property without just compensation.

Listen

Proceeds of crime legislation

Federal prosecutors are trying to seize the profits from his autobiography Guantanamo My Journey which has, since October last year, sold 30,000 copies.

Captured in Afghanistan, Hicks was detained for five and half years in Guantanamo Bay before pleading guilty to supporting terrorism.

He was repatriated to an Australian prison in May 2007 and released in December of that year.

Last week prosecutors using the federal Proceeds of Crime Act succeeded in freezing bank accounts pending a full trial

Listen

Justice Kevin Duggan

2 August 2011

Last week Justice Kevin Duggan stepped down from the Supreme Court of South Australia.

During his 46 years in the law he sentenced Snowtown (bodies in barrels) killer James Vlassakis, presided over ‘The House of Horrors’ child abuse trials and defended serial murderer James Miller.

But Justice Duggan doesn’t think lawyers and judges are the centre of the legal universe — he reckons jurors are the ‘unsung heroes of the system’.

Listen

Planning processes and houses of worship

26 July 2011

Have you ever tried obtaining planning approval to build or renovate a house? It’s not easy is it!

But when it comes to a ‘house of god’ planning processes can become a lot trickier. How do you distinguish genuine concerns about amenity from religious intolerance?

As difficult as these issues are here in Australia, they are nothing compared to the obstacles faced by some of our Asian neighbours’ religious minorities.

Listen

Ponki mediation

19 July 2011

Ponki: the word means ‘welcome’ in the language of the Tiwi islands. It also means ‘peace’ or ‘it’s finished’, and the spoken word is often accompanied by a hand gesture, waving the hand away from the body.

The ancient concept is now being combined with mainstream mediation techniques to resolve all sorts of conflicts and disputes.

It’s helping long serving prisoners reintegrate back into the community and helping troubled youth stay out of jail.

Listen

News, views, Practice Directions, events, forthcoming national and international conferences, CPD seminars and more …

The 2011 Supreme Court Oration

In this the sesquicentenary year of the Supreme Court of Queensland The Hon Paul de Jersey AC Chief Justice of Queensland has pleasure in inviting you to The 2011 Supreme Court Oration to be delivered in the Banco Court on Thursday, 15th September 2011 at 5.30pm by The Rt Hon Beverley McLachlin PC Chief Justice of Canada. Chief Justice McLachlin will be speaking on ‘The Courts and the Media’.

Rt Hon Beverley McLachlin PC

Rt Hon Beverley McLachlin PC was born in Alberta in 1943. In 1965, she was awarded a BA (Honours) in Philosophy at the University of Alberta. She continued her tertiary studies there, and in 1968, she received a MA in Philosophy and an LLB. Beginning in 1974, the Chief Justice taught at the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Law for seven years. In 1981, she was appointed to the Vancouver County Court and

four months later to the Supreme Court of British Columbia. She was appointed to the British Columbia Court of Appeal in 1985 and three years later, in 1988, she was sworn in as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia. In 1989, the Chief Justice was appointed as a Justice to the Supreme Court of Canada and she was elevated to Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada in early 2000.

The Chief Justice has been the recipient of 31 honorary degrees. In 2010, she was inducted into the International Hall of Fame by the International Women’s Forum and named Canadian of the Year.

RSVP

The oration will be followed by light refreshments in the Rare Books Precinct

RSVP before 12th September to marie.bergwever@justice.qld.gov.au or (07) 3247 4279

Awards Dinner 2011 – Womens Lawyers Association of Queensland

The annual awards dinner will be held on Friday, 9 September 2011 at the Brisbane Club. The dinner celebrates the achievements of three woman lawyers in the categories of Woman Lawyer of the Year, Regional Woman Lawyer of the Year and Emergent Woman Lawyer of the Year. The Queensland Law Society Agnes McWhinney Award will also be announced.

The speakers at the dinner are Elizabeth Fraser (Commissioner for Children and Young People and Child Guardian) and Judy Loughnan (General Counsel at Suncorp).

You don’t need to be a member of the WLAQ to attend and you don’t need to be female either!

For more information visit our website.

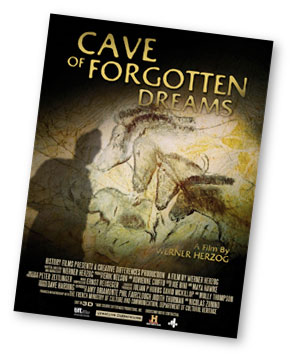

Film Release – Cave of Forgotten Dreams

Film Release – Cave of Forgotten Dreams

Following his previous documentary Encounters at the End of the World, iconic director Werner Herzog once again takes us deep behind the frontier of an extraordinary place. Having gained unprecedented access through the tightest of restrictions and overcome considerable technical challenges, he has captured on film, with specially designed 3D cameras, the interior of the Chauvet Cave in southern France. This is where the world’s oldest cave paintings — hundreds in number – were discovered in 1994. In the mesmerising Cave of Forgotten Dreams, he reveals to us a breathtaking subterranean world and leads us to the 32,000-year-old artworks. In that deeply moving moment of encounter, we come face to face with pristine and astonishingly realistic drawings of horses, cattle and lions, which for the briefest second come alive in the torchlight.

In true Herzogian fashion, his hypnotically engaging narration weaves in wider metaphysical contemplations as we learn more about the Paleolithic art and its creators. Through his understated and gently humorous voiceover, we are invited to reflect on our primal desire to communicate and represent the world around us, evolution and our place within it, and ultimately what it means to be human.

The film will be released on 22 September 2011.

For more information visit http://www.caveofforgottendreams.co.uk/

Special Preview

To celebrate the release of the film the Association has been offered 10 free passes to a special preview being held on Sunday 18 September at Dendy Portside at 4:00 p.m. Members interested in attending this event should email mail@www.hearsay.org.au to avoid disappointment.

The Supreme Court History Program Yearbook 2010 Now Available

The Supreme Court History Program Yearbook, now in its sixth year of publication, has proven a valuable addition to the libraries of historians and lawyers alike. As the only publication of its kind in Queensland, the Yearbook features scholarly articles on Queensland’s legal history, together with tributes to retiring judges, legal personalia and a review of significant judicial and legislative developments for the year. This volume serves as a significant resource for those seeking an overview and enduring record of the Queensland legal profession in 2010.

Download the order form here.

Justice for All Conference

12 – 15 February 2012

In February 2012, the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences and the Australian Human Rights Centre of the Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales will host an international conference Justice for All? The International Criminal Court – A Conference: A Ten Year Review. The conference will mark the 10th Anniversary of the operation of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and discuss the work and impact of the ICC during its first decade. The President and Registrar of the ICC will be attending the conference.

The two key objectives of the Conference are to examine the role and success of the ICC in achieving gender justice, and to analyse the participation of the Asia Pacific region in the ICC regime. The Conference will review the circumstances and reasons for the Asia Pacific’s limited engagement with the ICC, and the key lessons from other regions about how to achieve ratification and full implementation of the Court’s mandate, including in the area of gender justice. Against the backdrop of the two main themes of gender justice and the Asia Pacific, the Conference will consider the operation of the Rome Statute of the ICC at three distinct levels: within the Court itself, as between states parties, and between the ICC and civil society.

The Justice for All Conference will be held at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, from 13 – 15 February 2012. The three-day conference will include the Australian Human Rights Centre Annual Public Lecture. Speakers participating in the conference to date include the President of the ICC, Judge Sang-Hyun Song; the Registrar of the ICC, Ms Silvana Arbia; ICC scholars; and representatives from government departments and NGOs. The final day of the conference will be dedicated to capacity-building workshops with delegates from the region. The workshop is by invitation only.

The Conference will address questions, including:

⢠How effective has the ICC been in ensuring that gender justice informs its mandate, practice and procedure?

⢠What factors explain the limited engagement of states in the Asia Pacific region with the ICC?

⢠How does advocacy around the ICC fit into broader strategies for achieving gender justice and equality at the global, regional and national level?

⢠What is the future of the ICC (and similar tribunals) in putting an end to impunity for the perpetrators of crimes and contributing to the prevention of such crimes?

For more information please view our website at www.justiceforall.unsw.edu.au

Call for Papers: The 30th annual conference of the Australia and New Zealand Law and History Society

Customs House, Brisbane, 12-13 December 2011.

The 2011 conference theme — “Private Law, Public Lives” – examines the social dimensions of private law in history. Proposals from all jurisdictions are welcome. Proposals on non-theme topics in legal history also welcome.

Highlights of this year’s conference include twin keynote speakers: Professor John McLaren, professor emeritus, Law School, University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, and author of the forthcoming Dewigged, Bothered and Bewildered: British Colonial Judges on Trial (University of Toronto Press, 2011); and Professor Rosalind Croucher, President of the Australian Law Reform Commission.

Also, by special arrangement with the American Society for Legal History, we will be including a panel from the ASLH, including, among others, Professor Constance Backhouse, Distinguished University Professor, University of Ottawa and President of the ASLH, and Professor Chris Tomlins, Chancellor’s Professor of Law, University of California, Irvine.

Paper proposals, including paper title, abstract (300 words max.) and brief author bio, should be sent by email to the Conference Committee at lawhistconf@uq.edu.au by 14 July 2011.

Also see conference website: www.law.uq.edu.au/anz-law-and-history-conference

Earth Jurisprudence: Building Theory and Practice

Australia’s Third Wild Law Conference: 16-18 September 2011, Griffith University

The aim of the conference is to stimulate discussion about what Earth Jurisprudence can offer theories of law and governance, and to create a a space for the rigorous development of international and Australian doctrine in this new field of law.

Speakers include:

- Emeritus Professor Ian Lowe, Griffith University

- Cormac Cullinan, Enact International, South Africa and author of the book “Wild Law”

- Other confirmed speakers include:

- Chief Justice Preston, NSW Land and Environment Court

- Professor Doug Fisher, QUT

- Larissa Waters, Senator Elect

- Dr Chris McGrath, University of Queensland

- Jo-Anne Bragg, Qld Environmental Defender’s Office

For further information visit the conference website.

26th annual Calabro SV Consulting Family Law Residential

9—10 September 2011, RACV Royal Pines Resort, Gold CoastÂ

The 26th annual Calabro SV Consulting Family Law Residential program, proudly presented in partnership with the Queensland Law Society and Family Law Practitioners Association, is the premier annual conference program for family law practitioners in Australia. In response to delegate feedback, this year’s program features the traditional streams dedicated to children’s issues and property matters. New streams are devoted to practical techniques for advocacy, family law practice management and maintenance of resilience in practice.

Several members will be speaking at the event on various topics:

- Brad Farr SC, Acting Judge, District Court of Queensland – Best practice advocacy: Evidence and preparing for trials

- Guy Andrew – Preparing for a domestic violence hearing: How to effectively and successfully run a domestic violence hearing

- Jacoba Brasch will facilitate an expert panel of family law practitioners in discussing and debating ethical dilemmas for solicitors and barristers

- Federal Magistrate Jarrett, Federal Magistrates Court and James Linklater-Steele – Contravention and contempt

10 CPD points

Register online by 7 September 2011 (Earlybird closes 12 August 2011).

Asia-Pacific Coroners Society 2011 Conference

7-10 November 2011

The theme of this year’s conference is “Australasian coronial systems 20 years after the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody: achievements and challenges.” It has been 20 years since the watershed Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. It is widely recognised that the Commission was a catalyst for reform of the coronial systems of Australia. 20 years on, it is appropriate to reflect on how successful those reforms have been and to debate the future direction of coronial systems in Australasia.

Key speakers:

- Hal Wootten AC QC is a former NSW Supreme Court Judge and was a Commissioner to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

- Professor Derrick Pounder is Professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Dundee. He has extensive experience in the coronial systems of England and Scotland and also in relation to the investigation of deaths in custody internationally.

- Professor Colin Tatz AO is a sociologist with expertise in indigenous suicide and the coronial system.

Professor Diego De Leo is the Director of the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention and an internationally recognised suicidologist.

- Ian Freckelton SC is an eminent member of the Victorian Bar with extensive experience in the coronial jurisdiction.

Registration details can be found here.

IBA Annual Conference

Registration details and the preliminary programme information are now available for the 2011 IBA Annual Conference.

The Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, Dr Mohamed ElBaradei, will deliver the keynote speech at this year’s opening ceremony. A seasoned diplomat, Dr ElBaradei served three terms as Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); an autonomous intergovernmental organisation under the auspices of the United Nations. He is a staunch advocate of nuclear disarmament, and promotes open and fair standards to guide the peaceful use of nuclear technology for development. In October 2005, Dr ElBaradei and the IAEA were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts ‘to prevent nuclear energy from being used for military purposes and to ensure that nuclear energy for peaceful purposes is used in the safest possible way.’

In 2011, Dr ElBaradei emerged as a high-profile opposition figure in the Egyptian protests that culminated in Hosni Mubarak’s resignation. He continues to be a voice for change in Egypt’s march toward democracy, calling for open dialogue, transparent legal standards and respect for human rights.

The IBA Annual Conference is the opportunity for legal professionals from around the world to meet and discuss key developments across multiple jurisdictions. In the current uncertain economic climate, it is ever more crucial to be fully informed and to the best of our ability. As the global voice of the legal profession, the IBA is uniquely qualified to provide you with the skills and knowledge required to do so.

Register before Friday 29 July to receive the early registration discount.

LEADR mediation workshop – Brisbane 2011

Tues 11—15 October 2011

LEADR mediation workshops are recognised throughout Australia, New Zealand and Asia Pacific for the high quality program design, the interactive and experiential emphasis of the training activities and the exemplary skills of its facilitators.

This mediation workshop runs over five consecutive days meets the training requirements to progress to accreditation under the National Mediator Accreditation System and for accreditation with LEADR. It offers:

- A proven mediation process adaptable to different types of mediations

- Sound theoretical frameworks in which to embed process and skills

- Essential communication skills to explore issues and reality test

- Practical tools to keep parties focused

- Strategies to generate options and to break impasses

- Nine mediation role plays

- Personalised feedback from highly skilled mediators

- Carefully chosen and varied learning activities including plenary sessions, syndicate group discussions, simulations, fishbowls and video clips.

2011 Mediation workshops fees:

Early bird fee: $2838 incl GST (1 month prior)

Standard fee: $3113 incl GST

For further information visit http://www.leadr.com.au/mediationtraining-qld.htm

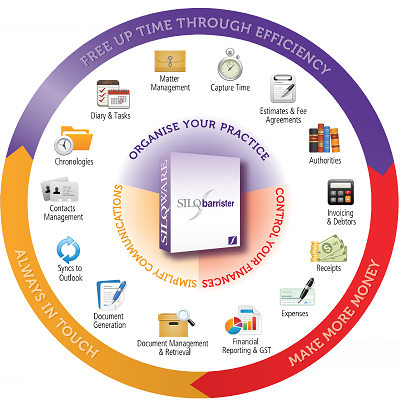

Bar Association of Qld Member Special Offer

10% off Standard Membership Fees

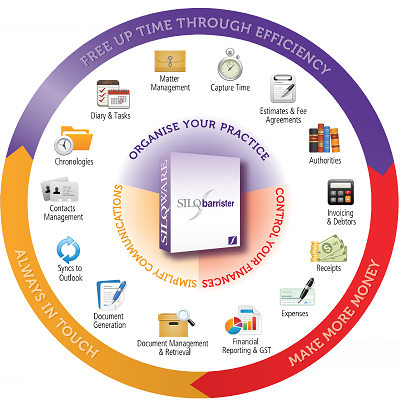

SILQ Barrister: Australia’s leading software for barristers. SILQ takes care of your business so you can spend more time on your business. Available on both Mac and PC

|

Download a FREE trial of a fully-functional version of SILQ Barrister.

|

|

|

| |

“When I started at the bar, my wise and insightful junior master gave me three tips: The first was ‘A judge’s joke is always funny’; the second: ‘no matter how hard, resist the temptation to refer to the UNCITRAL model law in every advice’ and the third was ‘get SILQ’.”

– Jo Chapple, QLD more …

“SILQ is indispensable in my private practice as a barrister. SILQ saves me time and money, and gives me unparalleled control over my practice and accounts. I would not dream of practising without it.

– Philippe Doyle Gray, NSW more …

“SILQ gives me complete control of my financials, and assists me to capture significantly more chargeable time. It therefore pays for itself many times over every year.”

– John Oswald-Jacobs, VIC more …

|

|

| SAVE TIME |

MAKE MORE MONEY |

TAKE CONTROL |

EASY TO USE |

SILQ takes care of the tedious administrative tasks you would otherwise spend hours on every week.

- Access all your matter and contact details in the one place.

- Automate document generation with your own, customisable letterhead and font (invoices, cost disclosures, cost agreements, chaser letters, faxes).

- Easily comply with Australian legislative requirements.

- Assess and report GST clearly, accurately and instantly.

|

SILQ is built around time costing so all your time can be billed — increasing your profit.

- Allows you to manage your business with minimal administrative support.

- Capture every minute with electronic time-entry.

- Issue invoices faster with automated document generation.

- Identify outstanding invoices at a glance; then generate chaser letters instantly.

- Reduce accounting and bookkeeping fees with streamlined reporting.

|

SILQ creates and tracks all financial and administrative tasks in one simple and easy-to-use environment.

- Quickly and easily generate graphs and reports to give you a clear overview of your business.

- Evaluate your financial situation instantly; the work you’re doing, completed, billed and received.

- Automatically organise and store documents relating to any and every matter.

- Anticipate tax confidently, lodge BAS punctually and easily deal with end-offinancial year accounts.

|

SILQ’s layout is very user friendly and intuitive. If you need support, you’ll be speaking directly with a local expert who will guide you.

- SILQ has been designed from the ground up specifically for barristers by barristers.

- Since its launch in 2003, SILQ has been regularly upgraded based on feedback from some of the many hundreds of Australian barristers using the software.

- The user-interface has been designed for speed and simplicity.

|

Download a FREE trial of a fully functional version of SILQ Barrister.

|

|

For more information phone us on 1300 556689

|

Income Protection, Life Insurance, Trauma Insurance

CBD FITNESS is the specialist holistic corporate fitness provider for sedentary and time poor executive people within the Brisbane CBD and Metropolitan locations.

The Holistic Difference

- User friendly systemized exercise/ nutritional programs

- Nutrition consultations & one-on-one sessions available for fast results

- Objective focused groups — fat loss/ muscle & strength gains

- 12 week challenge

- Three sessions per week

Barcare Bootcamp Ongoing 12 Week Challenge

- Tuesday 6:30am — 7:30am (Roma Street Parklands)

- Wednesday 6:30am — 7:30am (Roma Street Parklands)

- Thursday 5:15pm — 6:15pm (Roma Street Parklands)

Next bootcamp start date — 28/06/2011 (members are invited to join anytime)

To register your interest contact:

Ph: 0406 600 999

Email: info@cbd-fitness.com.au

Barcare Bootcamp — Testimonials

“I’m not fit at all, but I really enjoy this part of my life. I wanted to create a routine of exercise in my excruciatingly busy week. I had no fitness to start with and no enthusiasm. Kent Cameron of CBD FITNESS, our trainer is patient, encouraging and inspiring. At first I could hardly move the next day, but I recommend it because you feel defended, strong the day after, able to handle more at work, eat with more awareness, and sleep better. Just getting out of the grind and on to the ground is very worthwhile, but to have that extra energy is great.”

Jane Oliver, HR Manager, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Legal Service (Qld).

I enrolled in Barcare Bootcamp ten weeks ago and I have been greatly impressed with both the manner in which the sessions have been conducted and the results that I have obtained. Going from almost no substantial physical exercise to relatively intense regular workouts was not easy, but it was something that I managed to do without injury or illness. I have been greatly impressed by the way in which the individual needs of members are handled at each session, without detracting from the general focus on obtaining the best possible results. I would highly recommend Barcare Bootcamp to anyone who wishes to avoid the pains and penalties caused by the generally sedentary aspects of life at the Bar.

Andrew N. S. Skoien – Barrister at Law [Skoien needs a lot of help – Ed.]

“Bootcamp is great fun. Kent Cameron (the personal trainer) puts you through your paces with a mixture of cardio and weights, and manages to tailor the sessions for the fitness and strength each participant. You’re always pushed, but never too far. Bootcamp is a great way to catch up with your colleagues and get in shape. It’s also a refreshing way to clear your head and de-stress at the start or end of the day. Good stuff!”

Steven Hogg — Barrister at Law

“I am a late bloomer when it comes to exercise and sports. I have not been allowed to play sports when growing up because I was a bad asthmatic. I used to just sit on the sideline and watched others play. I was unfit but not overweight.

6 yrs ago I decided to give running a go and loved it, I was never fast but have completed 10-12 k fun runs in a reasonable time over the yrs. I also learnt to cycle 4yrs ago and regularly cycle with 2 other women in the weekends, and have done several long distance rides, which encompassed hills.

Unfortunately 13 months ago, an MRI scan showed slow degeneration of my right knee joint, which has now severely hampered my ability to run.

When the Bar Association advertised the exercise program I was skeptical as to what possibly could any trainer do for me. However I signed up for it, and was hoping that I would meet a PT who could help me to run pain free (if that was realistic) and to improve my endurance on hills when riding! I had some reservations when I signed up. Having tried the program I love it!

Kent is a tremendous PT! He took into account my rehabilitation needs and personalized my training schedule to allow me to maximize my potential. I am very slowing regaining ability to run with less pain, but the most surprising thing was I have so much more endurance when cycling uphill. – No more cramps, reduced breathlessness and I am actually enjoying climbing hills! I am definitely sticking to my training with Kent and come September 2011, I will be ready to tackle the hilly holidays in Norway on a bicycle!

One other important factor- the people who make up the group I go to twice a week are really great and fun to work out with. We have different needs but we are a cohesive group. Kent tries very hard to tailor to all our needs. He is very encouraging which in turn makes me want to give my very best even though some days when I attend.”

Elvira Jorgensen, Barrister, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Legal Service (Qld).

I recently commenced training with Kent Cameron of CBD Fitness — “Barcare Bootcamp”. Kent is diligent and professional with the group sessions I have undertaken with him to date. He structures the sessions in a manner in which sub-groups are formed to match your level of fitness. Being reasonably fit, I like the challenges Kent implements for me. Notwithstanding the group sessions format, Kent also places emphasis on the individual and the progress of each member of the group is paramount to Kent’s training methods. The members of the group I have trained with are professionals with a sociable and friendly disposition who encourage each other during the sessions. The sessions are in effect a mixture between hard work and friendly banter between participants, which I thoroughly enjoy. The early morning sessions have been a great way to start the day and my energy levels and work productivity have improved as a result.

CBD Fitness has contributed considerably to the recent betterment of my life. I am sure that no matter what your level of fitness may be or what objectives you may wish to achieve from your training, that CBD Fitness will be able to assist you. I strongly vouch for CBD Fitness to assist with all your training needs.

John Castanho Former Lawyer. Now writer and Investor.

Over one hundred UQ law students applied to undertake a work experience placement as part of the BWEP. Of these, thirty were shortlisted for an interview. The final twelve were selected as high achieving well-rounded students eager to experience life at the bar and were then carefully matched with one of the participating barristers or chambers.

The following list is of the barristers and/or chambers, including four Senior Counsels, and the student(s) they have generously undertaken to provide a work experience placement to through the BWEP:

- A. Brian Balzamo (Level 14 Inns of Court) & Chrysa Samios

- Ken Barlow S.C. (30 West Chambers) & Joshua Lee

- Matthew Black (Quay 11 Chambers) & Grace Devereaux

- Sandy Horneman-Wren S.C. (Level 19 Inns of Court) & Zac Worrall

- John McKenna S.C. and Dominic O’Sullivan (Levels 16 & 17 Quay Central Chambers) & Stephanie Colquhoun and Mikhara Ramsing

- Richard Lynch (More Chambers) & Kerrie Hales and Charles Martin

- Daniel Morgan (Level 27 East Chambers) & Claire Hockin

- Greg Smart (Sir Harry Gibbs Chambers) & Anthony Gardner

- Michael Stewart S.C. and Dominic Pyle (Gerard Brennan Chambers) & Claire Morris and Alex James

It is anticipated that for their forty hours of work experience these students will undertake legal research and administrative tasks, as well as shadow their barrister to court and meetings. It is hoped that this experience will develop the legal skills of participating students and provide them an invaluable insight into a career at the bar.

The vision of BWEP is to begin a welcome and much awaited relationship between two legal institutions — the bar and the law school — that will see the more exceptional law graduates distinguishing themselves for a career at the bar. For too long Eagle Street has actively solicited the interest of law students, while North Quay has remained shrouded in mystery knowable only to those lucky few students with barristers as family members or friends.

Commercially motivated law firms sponsor university law societies in order to develop their presence on campus, as well as running clerkship programmes to capture the intrigue of the best and brightest law students. Cumulatively, by educating students and providing them opportunities alongside solicitors, these endeavours have created a relationship between law firms and law students that cause students to aspire toward a career as a solicitor with a view to becoming a partner of a renowned law firm.

Commercially motivated law firms sponsor university law societies in order to develop their presence on campus, as well as running clerkship programmes to capture the intrigue of the best and brightest law students. Cumulatively, by educating students and providing them opportunities alongside solicitors, these endeavours have created a relationship between law firms and law students that cause students to aspire toward a career as a solicitor with a view to becoming a partner of a renowned law firm.

The vision of the BWEP is to see such a relationship develop between law students and barristers. A relationship in which students are educated about what barristers do and how to become one, a relationship in which students are provided opportunities to experience life in chambers and court, which is a relationship that will see students aspire to a career at the bar.

Accordingly the BWEP is designed to nurture the enthusiasm of high achieving and well rounded students and to do so at a pivotal point in their degree. The BWEP will not only facilitate students learning what steps are necessary for them to become a barrister, such as postgraduate study, associateships and/or working in litigation, but will also energise them to take these steps and forge their path to the bar.

While attracting exceptional law students is a business strategy for law firms, for the bar and in fact the bench it is the only way to ensure continued prestige and legitimacy. We need brilliant students to become barristers and serve as advocates, advisers and more importantly to enable the bar to supply the next generation of judges. Accordingly it is imperative that the bar promote itself and be accessible to law students through initiatives such as the BWEP.

In 2011 the BWEP is a pilot initiative, but with a view to benefiting many more law students and ultimately the bar, the UQLS looks forward to the support of barristers and chamber groups as it works with the BAQ to develop this programme into the future. It is anticipated that the programme will be grown until it is of sufficient capacity to support law students from other Queensland universities.

The UQLS sincerely appreciates the time and energy each of the barristers involved will be giving over the next two months to mentor their student, and open their eyes to the world of chambers and court. The UQLS would like to specifically thank Helene Breene and Celeste Baker of the BAQ, and Dominic O’Sullivan from Quay Central 16 & 17 chambers, for their tireless support of the BWEP.

The UQLS sincerely appreciates the time and energy each of the barristers involved will be giving over the next two months to mentor their student, and open their eyes to the world of chambers and court. The UQLS would like to specifically thank Helene Breene and Celeste Baker of the BAQ, and Dominic O’Sullivan from Quay Central 16 & 17 chambers, for their tireless support of the BWEP.

If you would like more information on the BWEP, or wish to communicate your interest in participating in the 2012 BWEP, please feel free to contact Michelle Delport by email at m.delport@uqls.com

Michelle Delport

Vice-President (Professional Sponsorship & Careers)

University of Queensland Law Society

Photo: UQ Steele Building and The Great Court by Gaz

The approach of the courts to litigants in person

There is clearly a tension between the need to provide protection to parties from vexatious and unnecessary litigation on the one hand and the need to protect the rights of parties to bring to the Courts claims and grievances which they reasonably have.

Experience and consideration of the cases shows that it inevitably follows that it is litigants in person who are more likely to fall foul of the vexatious litigation provisions.

However, the Courts have consistently recognized the need to accommodate litigants in person and to extend to them indulgences which, generally speaking, are not available to litigants who are represented by solicitors or counsel.

In the recent decision in the Court of Appeal of Queensland in du Boulay v Worrell & Ors [2009] QCA 63 Muir JA at [68] — [69] said:

“[68] The appellant appears to have succumbed to the phenomenon which inflicts many self-represented litigants of becoming so fixated on real or perceived wrongs that he has lost any semblance of objectivity and the power of discrimination. It does not appear to have occurred to him that by heaping allegation on allegation he has put it beyond his ability to plead, let alone conduct and finance his case. Nor does it appear to have occurred to him that the myriad of allegations has a tendency to destroy whatever credibility may have attached to a case involving fewer allegations more obviously supported by clearly identified material facts.

[69] It may be that self-represented litigants should be afforded a degree of indulgence and given appropriate assistance.22 But if a self-represented person wishes to litigate, he or she is as much bound by the rules of Court as any other litigant. Those rules exist to facilitate efficient, fair and cost-effective litigation. The Court’s duty is to act impartially and ensure procedural fairness to all parties, not merely one party who may be disadvantaged through lack of legal representation. The other party to the litigation is entitled to protection from oppressive and vexatious conduct regardless of whether that conduct arises out of ignorance, mistake or malice.”

In that decision Muir JA referred to Bhagat v Global Custodians Limited [2002] FCA 223 and Rajscki v Scitec Corporation Pty Ltd (unreported, Supreme Court of NSW, Court of Appeal, 16 June 1986).

In Bhagat v Global Custodians Limited (supra) the Federal Court Court of Appeal at paragraph 12 it is said as follows:

“[12] Mr Bhagat is a vigorous litigant. He told the Court that he is presently engaged in over thirty separate sets of legal proceedings, many, and perhaps most, of which directly or indirectly involve the judgment creditor. Fortunately, it will not be necessary for the Court to examine all those proceedings, but it will be necessary, because of the numerous documents to which Mr Bhagat took us, to refer to some of them. Some indication of the intensity with which these proceedings were litigated may be gauged from the fact that the judgment creditor, notwithstanding that it was the respondent to Mr Bhagat’s application for leave to appeal, prepared the Appeal Book and lodged no less that seven volumes of various materials comprising, in all, 2528 pages. Mr Bhagat was not, however, satisfied that the Court would be sufficiently benefited by this generous amount of material: he filed a further 4353 pages of pleadings, affidavits and exhibits to affidavits which he had extracted from his many pieces of litigation. (That number does not include the several documents that Mr Bhagat handed up during the course of his submissions). It transpired, during the course of the hearing, that the greater part of the material that had been included in the Appeal Book had not been before the primary judge and should not have been placed before this Court. This application had been rushed into the November 2001 Full Court hearings on short notice and without the benefit of a Deputy Registrar exercising control over the contents of the Appeal Book. The proliferation of paper in this application shows that there is a need for such control, particularly in those cases where a party is unrepresented.”

The approach of the Courts is to try to assist litigants in person but there are limits. However, litigants in person are still bound by the law of evidence and the rules of procedure. Care must be taken to ensure that the assistance given to litigants in person is not such that other parties form the belief, either real or imagined, that the litigant in person is being favored or given an unfair advantage.

There are a number of aspect which are frequently associated with litigants in person which can cause or contribute to litigants in person becoming vexatious litigatnts.

Passionate Obsession with the Cause of Action

An examination of a number of the cases (I have set out citations to such at the end of this paper) where vexatious litigant applications have been considered, show that the litigants often have a strongly held belief, that they have been treated unfairly and on occasion oppressively and perhaps dishonestly by Government Departments, large and seemingly powerful corporations or institutions such as Universities.

When litigants with similar passionate beliefs instruct legal practitioners and engage them to conduct their litigation they will, at least usually, receive advice from ther legal practitioners which identifies the areas of disputation which are appropriate to include in the proposed litigation. Often many of the complaints which are raised by litigants in person are matters which, although possibly relevant to questions of background and circumstance, are not matters which can be, either practically or as a matter of law, determined by the Courts. Moreover, they are often simply irrelevant and scandalous.

Frequently, the litigant in person confuses the difference between what is and what is not relevant and by combining within the proceedings numerous complaints and ill considered remedies, the proceedings become unmanageable and on occasion indecipherable. The pleadings are often simply a stream of consciousness.

The unfortunate aspect of that is that often, litigants in person do have a reasonable and proper basis for seeking redress, but it is so overwhelmed by the nature of the proceedings that it gets mixed in the morass of the action such that it is lost along with other unmeritorious claims.

Absence of an Adverse Cost Order Disincentive

Experience would suggest that often the vexatious litigant in person is either a corporation or a natural person who has little or nothing in the way of assets. In the usual course of litigation, parties must constantly be conscious of the risk of not only their own legal costs associated with the litigation, but also the risk of adverse cost orders being made against them. The litigant in person who has no practical exposure to any adverse cost order is not likely to give any weight to the risk of such orders. So that one of the “realities” of litigation which have a real impact upon the manner in which litigation is conducted and in particular the willingness to attempt to settle proceedings, is missing. It clearly gives the litigant in person a distinct advantage and lever.

This also is a concern for persons attempting to mediate these dispute as one of their prize weapons, “the costs…think of the costs..” does not work.

Whilst in the case of a corporate litigant, the other parties have the opportunity of seeking orders for security of costs under the relevant Rules of Court Chapter (17 of the Queensland Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999) or s.1335 of the Corporations Act 2001 and arguable, the inherent power of the superior Courts, such a process is not readily available where the litigant in person is a natural person.

Whilst it is not impossible to seek an order for security of costs against a natural person it is obviously only in fairly rare and extreme circumstances that it is granted. This is particularly so where there are other enlivening circumstances such as absence from the jurisdiction or bringing the proceeding in a representative capacity.

It seems to me, that it would not be unreasonable for a Court, when dealing with a person who had habitually and unreasonably commenced litigation to have regard to those facts when considering whether or not an order for security of costs should be made. That pre-supposes that at that stage, no order under any of the vexatious litigation acts or regulations has been made with respect of that person.

Prolixity of Documents

Most probably because of the intensity of feeling about the proceedings, the need to tell the litigant’s story in detail to someone in authority and a lack of understanding of the proper forms and procedures for commencing and conducting litigation, it is frequently the case that the documentation and inevitably the statement of claim and other pleadings, are prolix and indecipherable.

It seems as if the litigant in person is determined to tell the story and to tell it in a forum where the person believes maximum exposure will be given to the perceived “wrongs” and often alleged “criminal” conduct of their opponents.

Forum Swapping