‘The proceedings reveal a strange alliance. A party which has a duty to assist the court in achieving certain objectives fails to do so. A court which has a duty to achieve those objectives does not achieve them. The torpid languor of one hand washes the drowsy procrastination of the other.’1

To become a legal practitioner, that is to say, a lawyer who may represent the modern client, a law graduate must present for admission and take either an oath or make an affirmation. In Victoria, and similarly in other jurisdictions, this oath or affirmation requires the candidate to declare that they will well and honestly conduct themselves in the practice of their profession, as members of the legal profession and officers of the court. It is the taking of the oath or affirmation, and the signing of the roll, that marks the transition from simply holding a law degree to being a lawyer. It is on this occasion that a lawyer’s duty to the court is enlivened.

A candidate presenting for admission today may hope to gain any number of benefits. One might have aspirations to advise publicly listed Blue Chip clients on ASX compliance, while another might wish to defend the criminally accused. Both will go on to perform very different duties as lawyers, however, both candidates will owe the same duty to the court.

In this paper, I will examine the content of the duty to the court in a number of contexts. I will reflect on some of the challenges that arise when that duty comes into conflict with practical and commercial pressures on lawyers. I will also discuss recent legal developments that strengthen and expand the duty to the court.

Let us start by examining a recent case from Victoria in which counsel failed in his discharge of the duty to the court. The case demonstrates that even senior counsel can fall into difficulty in observing the duty.

Let us start by examining a recent case from Victoria in which counsel failed in his discharge of the duty to the court. The case demonstrates that even senior counsel can fall into difficulty in observing the duty.

Rees v Bailey Aluminium Products2 was an appeal from a civil jury trial grounded in a complaint by the appellant that he did not receive a fair trial as a consequence of the conduct of senior counsel for the respondent. The case at first instance was a claim for damages for personal injuries brought against the respondent as the manufacturer and distributor of an extension ladder. The appellant had fallen from the ladder, which had been set up for him by a third party (also a party to the proceedings), in an over-extended position.

It was conceded on appeal that senior counsel for the respondent had, during cross-examination, sought to convey that the appellant and the third party had engaged in a conversation in the court precinct which amounted to them conspiring to pervert the course of justice. The intimation was that they were planning to fraudulently implicate the respondent as being responsible for the applicant’s accident, thereby exonerating the third party. However, no evidence was adduced to support this allegation and it was not put to the appellant, a clear breach of the rule in Browne v Dunn.

In fact, the cross-examination was based upon the personal observation by senior counsel for the respondent of the appellant and the third party in discussion outside the court building. Further criticism was made of the method of cross-examination in relation to counsel repeatedly cutting the witness off, treating his own questions as answers of the witness and disregarding the trial judge’s repeated interventions.

The Court of Appeal held that the various aspects of the conduct of senior counsel for the respondent during the trial had breached the duty to the court. The Court noted that an allegation of fraud with no factual basis ‘constitutes a serious dereliction of duty and misconduct by counsel’ and that the obligation not to mislead the court or cast unjustifiable aspersions on any party or witness arises as part of the duty to the court.3

Other examples of senior counsel’s dereliction of his duty to the court are also described in the judgment, including a failure to comply with a ruling of the trial judge, failures to meet undertakings provided to the trial judge and the introduction of extraneous and prejudicial matters in the closing address.

The case makes for instructive reading and is a signal that practitioners must remain ever mindful of their role as officers of the court and the standards of professional conduct that must attend such a position. The desire to win a case has no part to play in the assessment by a practitioner of their responsibility towards the court. The duty to the client is subordinate to the duty to court. There is a line between permissibly robust advocacy and impermissible dereliction of duty. It is incumbent upon practitioners to continue to examine the ethical dimensions of their behaviour and consider their actions in the context of their role as officers of the court.

Another well established aspect of the lawyer’s duty to the administration of justice is assisting the court to reach a proper resolution of the dispute in a prompt and efficient manner.

Another well established aspect of the lawyer’s duty to the administration of justice is assisting the court to reach a proper resolution of the dispute in a prompt and efficient manner.

As judges experience daily, the legitimate interests of the client are usually best served by the concise and efficient presentation of the real issues in the case. Nevertheless, some clients have an interest in protracted legal proceedings. This cannot be given effect by lawyers if they are to act consistently with their duty the court.

In A Team Diamond4 the Victorian Court of Appeal observed that the obligation is now more important than ever ‘because of the complexity and increased length of litigation in this age’. Without this assistance from practitioners, ‘the courts are unlikely to succeed in their endeavour to administer justice in a timely and efficient manner.’5

In the recent Thomas v SMP6 litigation in the Supreme Court of New South Wales, Pembroke J faced the prospect of a 500 page affidavit, filed by one of the parties to the proceeding, which contained mostly irrelevant material. Doing his duty, his Honour embarked on a close, line by line, examination of the objections which had been made to the affidavit, and noted that it was a ‘time consuming, painstaking but ultimately unrewarding task.’ After 3,000 paragraphs, his Honour ceased, proclaiming that he ‘could go no further’, finding it ‘inappropriate’ to rule on each and every objection. The inappropriateness arose not necessarily from the contents of the affidavit â despite this being a problem in of itself â but from what his Honour described as counsel’s failure to do right by the court. His Honour said that ‘counsel’s duty to the court requires them, where necessary, to restrain the enthusiasms of the client and to confine their evidence to what is legally necessary, whatever misapprehensions the client may have about the utility or the relevance of that evidence.’ He found that ‘in all cases, to a greater or lesser degree, the efficient administration of justice depends upon this co-operation and collaboration. Ultimately this is in the client’s best interest’.

Heydon J, writing extra-curially in 2007, observed that ‘modern conditions have made [the duty the court] acutely difficult to comply with. Every aspect of litigation has tended to become sprawling, disorganised and bloated. The tendency can be seen in preparation; allegations in pleadings; the scope of discovery; the contents of statements and affidavits; cross-examination; oral, and in particular written, argument; citation of authority; and summings-up and judgments themselves.’7 With this in mind, Pembroke J’s finding that counsel’s duty to the client is an obligation subsumed by and contingent upon the duty to the court, is compelling. It is a view that is coming to prominence in many Australian jurisdictions, both legislatively and jurisprudentially.

Most would agree in principle that the inherent objective of the lawyer’s overriding duty to the court is to facilitate the administration of justice to the standards set by the legal profession. This often leads to conflict with the client’s wishes, or with what the client thinks are his personal interests.8 The conflict between the duty to the court and to the client has been described by Mason CJ as the ‘peculiar feature of counsel’s responsibility’.9 The Chief Justice also observed that the duties are not merely in competition. They do not call for a balancing act. They actually come into collision and demand that, on occasion, a practitioner ‘act in a variety of ways to the possible disadvantage of his client … the duty to the court is paramount even if the client gives instructions to the contrary.’10

Whilst we may fall in agreement on the fundamental nature of the duty to the court, Thomas v SMP, and many other cases, demonstrate that its application in practice is not always as straight forward as would appear. The burden of being a lawyer lies in the lawyer’s obligation to apply the rule of law and in the duty ‘to assist the court in the doing of justice according to law’11 in a just, efficient, and timely manner.

Chief Justice Keane has observed some of the conceptual and practical difficulties posed by the duty to the court. In an address to the Judicial College of Australia in 2009, in which his Honour offered perspectives on the torts of maintenance and champerty in the context of modern day litigation, the Chief Justice noted that ‘in the traditional conception, the courts are an arm of government charged with the quelling of controversies … the courts, in exercising the judicial power of the state, are not “providing legal services”. The parties to litigation are not acting as consumers of legal services: they are being governed â whether they like it or not.’12 His Honour went on to observe that ‘when lawyers act as officers of the court, they … are participating in that aspect of government which establishes, in the most concrete way, the law of the land for the parties and for the rest of the community.’

Chief Justice Keane has observed some of the conceptual and practical difficulties posed by the duty to the court. In an address to the Judicial College of Australia in 2009, in which his Honour offered perspectives on the torts of maintenance and champerty in the context of modern day litigation, the Chief Justice noted that ‘in the traditional conception, the courts are an arm of government charged with the quelling of controversies … the courts, in exercising the judicial power of the state, are not “providing legal services”. The parties to litigation are not acting as consumers of legal services: they are being governed â whether they like it or not.’12 His Honour went on to observe that ‘when lawyers act as officers of the court, they … are participating in that aspect of government which establishes, in the most concrete way, the law of the land for the parties and for the rest of the community.’

The increasing commercialisation of legal practice represents a challenge to this ‘traditional conception’. In recent times, legislative amendments and a form of self-deregulation resulted in the abolition of various practices that were viewed as restrictive, such as the use of scale fees and the prohibition on advertising. A shift towards a liberal economic model and a focus on free market principles have also resulted in many law firms moving towards operating under modern business models, and away from the traditional partnership paradigm.

These factors and the ‘move towards the incorporation of legal practices, the commercial alliance between legal practices and other commercial entities and, more recently, the public listing of law firms on the stock exchange’ have all contributed to the ‘commercialisation’ of the profession.13 This has raised concern amongst members of the profession, the judiciary and regulators. As Mason CJ expressed extra-curially, ‘[t]he professional ideal is not the pursuit of wealth but public service. That is the vital difference between professionalism and commercialism.’14

The shift toward commercialism has, in part, been a response to the needs and demands of clients and the changing business environment in which law firms operate. However, the commercial interests of both the law firm and the client do not necessarily tend towards the efficient use of court time and resources, meaning that this aspect of the practitioner’s duty to the court can come into conflict with the duty to the client.

The Law Reform Commission of Western Australia has recognised that this is particularly a problem when lawyers act for well-resourced clients. These clients are able to pursue every avenue for tactical purposes, are able to claim legal fees as tax deductions and need not have regard to the burden of litigation on the taxpayer.15

The system of charging by billable hours could also be said to be a disincentive for lawyers to settle matters expeditiously, and has been criticised as inefficient from a market point of view. It is now appropriate to rethink the system of billable hours in certain contexts. For example, certain transactional work that fits into a defined time period may lend itself to a negotiated fee, rather than a billable unit or rate.

The system of charging by billable hours could also be said to be a disincentive for lawyers to settle matters expeditiously, and has been criticised as inefficient from a market point of view. It is now appropriate to rethink the system of billable hours in certain contexts. For example, certain transactional work that fits into a defined time period may lend itself to a negotiated fee, rather than a billable unit or rate.

With economic considerations increasingly gaining ascendance over older notions of professionalism, lawyering now viewed as a commercial activity, and the law as an industry, it is hardly surprising that clients of law firms are increasingly being viewed as consumers. This shift works both ways; users of legal services also view themselves as consumers. Again, such a mindset is not novel to the legal market. It is the result of a change in economic practices and social values generally.

The tendency toward viewing the client as a consumer, stemming from a shift towards a liberal economic paradigm, affects the way the duties to the client and the court interact. Consumers generally are becoming increasingly aware of the market power they wield; the market for legal services is no different.

It is of no great surprise then that the commercial aspect of the notion of legal professionalism, that is the provision of a skilled service to paying clients, has become more prominent and begun to resemble the rest of the commercial world. As several former High Court judges have noted in speeches over the years, the advertising of legal services was once unthinkable. Now it is commonplace.16

The era of the grand social institutions has given way to the era of commerce and the consumer. As Chief Justice Spigelman has observed, the administrative buildings whose stately forms once dominated city skylines are now dwarfed by commercial high-rises.17 Barristers working in Owen Dixon chambers now look out over and far above the adjacent dome of the Supreme Court of Victoria, once Melbourne’s tallest building.

The dual role of legal practitioners, as officers of the court and, at the same time, as service providers, has evolved and will continue to do so in line with broader changes occurring within and between administrative and commercial institutions, and in line with changing social values.

The evolution of the industry in this regard is not easy to manage, nor is it unmanageable. We cannot ignore the changes that are occurring, or reminisce about days gone by. I continue to believe that, in general, lawyers want to discharge their professional responsibilities competently; and that engendering legal ethics is best begun at the undergraduate level and maintained throughout the career. Lawyers continue to behave ethically, despite the changing legal environment. However, such changes demand that we review and strengthen some of the principles that were developed around concepts of professionalism, including the effective discharge of the practitioners’ duty to the court.

The duty to the court remains the very foundation of our dispute resolution system. The duty to the court is thus at the core of all litigation, be it civil or criminal. Theoretically, therefore, it’s purpose should be engrained in the very fabric of our dispute resolution methods. But is it?

We recall the often quoted judgment of Heydon J in AON v ANU in which his Honour described the vicious cycle of inefficiency that arises when the objectives of the duty to the court are forgotten â ‘[proceedings often reveal a strange alliance] … a party which has a duty to assist the court in achieving certain objectives fails to do so. A court which has a duty to achieve those objectives does not achieve them. The torpid languor of one hand washes the drowsy procrastination of the other.’

It seems fitting then to consider the extent to which legislators and courts are attempting to redress the consequences of this ‘languor’. Both have readily sought to establish broad principles that encapsulate the duty to the court as the paramount duty for all players in litigation. Courts and legislatures are on the same page; from both we are seeing the emergence of overriding principles which guide judicial intervention in proceedings where time and money are going to waste. At the core of this equation lies the duty to the court.

It is perhaps best to proceed chronologically. First, the High Court’s decision in AON v ANU. One commentator views the overall effect of the judgment as transforming the judicial role from that of passive decision maker to active manager of litigation.18 This shift was considered necessary by French CJ as a matter of public policy, his Honour observing that ‘the public interest in the efficient use of court resources is a relevant consideration in the exercise of discretions to amend or adjourn.’19 The Chief Justice spoke of the history of the Judicature Act Rules and their Australian offspring and noted that these did not make reference to the public interest in the expeditious dispatch of the business of the courts, resulting in this being left to the parties. However, he went on, ‘the adversarial system has been qualified by changing practices in the courts directed to the reduction of costs and delay and the realisation that the courts are concerned not only with justice between the parties, which remains their priority, but also with the public interest in the proper and efficient use of public resources.’ The plurality, (Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ) spoke of the ‘just resolution’ of proceedings remaining the ‘paramount purpose’ of the procedural rules in dispute in the case.

Looking at all of the judgments collectively, the High Court’s approach in AON was one of objectives. The court held that the adjournment of the trial and the granting of leave to ANU to amend its claim was, in those circumstances, contrary to the case management objectives set out in the ACT Court Procedures Rules 2006. The purpose of those rules, like most Superior Court rules around Australia, is to facilitate the just resolution of the real issues in civil proceedings with minimum delay and expense.20

One immediate consequence of the judgment is that for a lawyer to discharge the duty to the court when seeking to amend pleadings or other court documents at a late stage in the proceedings, he or she will need to consider and abide by the objective of the procedural rules in question, and to be able to demonstrate how the objective of the amendment is consistent with that purpose.

In rejecting the submission that the ability to amend court documentation at any time is a procedural right of the parties, the court explicitly stated that a considered approach to the objective of the procedural application in question is necessary. So, being able to account for the reason for the delay and demonstrate that the application is made in good faith may be relevant to a lawyer’s exercise of the duty to the court. Other factors which may be taken into account by the court in assessing such applications might be the prejudice to the other parties in that litigation, or in other litigation awaiting a trial date, the costs of the delay, or the status of the litigation.

The language and directions of the High Court in AON correspond to the language and purpose of recent and fundamental legislative developments in Victoria, and federally.

The Victorian Civil Procedure Act 2010, which came into operation on 1 January this year, is the first Victorian Act to be directed solely, and in broad terms, to civil procedure in Victoria. The Act establishes an ‘overarching purpose’ which also applies to the rules of court. The goal of the overarching purpose is to facilitate the just, efficient, timely and cost-effective resolution of the real issues in the parties’ dispute. The overarching purpose may be achieved by court determination, agreement between the parties, or any other appropriate dispute resolution process agreed to by the parties or ordered by the court.

Of course, aspirational statements of this kind are not unfamiliar. Rules advocating efficient and just determination of disputes have existed in many of the Superior Courts in the States and Territories for years.21 The fundamental difference is that here, the overarching purpose is a legislative command to which the courts are to give effect in the exercise of their powers.22 This imperative takes a number of novel dimensions. Specific obligations are imposed upon a greater range of participants, with greater specificity as to their obligations than has ever been seen before. The obligations apply equally to the individual legal practitioner and to the practice of which they are a part,23 to the parties themselves, any representative acting for a party, and anyone else with the capacity to control or influence the conduct of the proceeding.24 Furthermore, s 14 of the Act states that a legal practitioner or a law practice engaged by a client in connection with a civil proceeding must not cause the client to contravene any overarching obligation.

Under this Act, a legal practitioner is in a different position to a practitioner refusing to act on an instruction which conflicts with their common law duty to the court. Whereas previously, the advice to the client in such a context would have been that the law did not allow the practitioner to follow that instruction, the advice under the new Act would likely be that the instruction is contrary to the client’s own obligations, with the secondary advice that the practitioner is bound to ensure that the client does not contravene that obligation.

The Act provides broad powers to the courts in relation to breach of the overarching obligations. The most common means by which a contravention is likely to be dealt is by taking the contravention into account when making orders in the course of the proceeding, most frequently in the form of costs orders.

Critical to our present discussion is s 16 of the Act, which directs that each person to whom the overarching obligations apply has a paramount duty to the court to further the administration of justice. The primacy of the paramount duty to the court is intended to ensure that the rulings and directions of the Court are not second-guessed in the name of overarching obligations.

Similarly, at the Federal level, the Access to Justice (Civil Litigation Reforms) Amendment Act 2009 (Cth) incorporated an ‘overarching purpose’ principle into the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976. Section 37M of the Federal Court Act now provides that the overarching principle is to facilitate the just resolution of disputes according to the law as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible. Under s 37N, parties have a duty to conduct the proceeding in a way that is consistent with the overarching purpose, and their lawyer has an obligation to assist them in fulfilling this duty. The new Federal Court Rules 2011 have introduced changes along similar lines. For example, r 20.11 provides that:

A party must not apply for an order for discovery unless the making of the order sought will facilitate the just resolution of the proceeding as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible.

So, we see both the courts and legislatures attempting to draw all parties in civil litigation away from unnecessary distractions to focus on the overarching purposes of dispute resolution, that is, the just, efficient, timely and cost-effective resolution of the real issues between the parties under the umbrella of the paramount duty to the court.

So far, my observations have been rather sanguine. I wonder whether it will all be smooth sailing from here and what problems are likely to be encountered in the application of these principles. Previously, the civil procedure reforms proposed pre-action protocols, which the new Victorian government has now repealed.25

I wonder also whether such hope might be found in criminal matters, or matters involving self-represented litigants. I would like to explore these questions by reference to three examples: civil penalty proceedings brought by ASIC, the exercise of the prosecutorial duty, and civil litigation involving self-represented litigants.

In the Morley v ASIC26 case, the NSW Supreme Court of Appeal (Spigelman CJ, Beazley and Giles JJA) overturned a finding that seven former non-executive directors of James Hardie had breached their duty to the company. At trial, ASIC contended that the former directors had breached their duty to the company by approving the release of a statement that misleadingly asserted that asbestos claims would be fully funded. The Court of Appeal found that the regulator had failed to prove that fact. To do so would have required the calling of a key witness of central significance to the critical issues in the proceedings, which ASIC â a model litigant owing the obligation of fairness â had decided not to do.

Applying the Briginshaw test, the court found that ‘the duty of fairness cannot rise higher than that imposed on prosecutors with respect to their duty to call material witnesses. In that respect … the court will not [readily] intervene [but] the ex post facto assessment of the decision not to call a particular witness must be taken in the overall context of the conduct of the whole of the trial.’ A tribunal of fact may have regard to any failure to provide material evidence which could have been provided. The tribunal’s state of satisfaction turns on the cogency of the evidence adduced before it. ‘Relevant to the cogency of the evidence actually adduced is the absence of material evidence of a witness who … should have been called …. [absent which the] court is left to rely on uncertain inferences.’

So, the duty to ensure a fair trial is an element of the duty to the court, just as the duty to assist the tribunal of fact to establish the necessary state of mind is also. The application of the Briginshaw test in this instance really was the court’s way of requiring ASIC to fulfil its duty to the court; ‘the duty of fairness and a fair trial cannot rise higher than the duty to the court … such duty forming part of the overarching duty in favour of which all conflicts are resolved.’ It is for legal practitioners to identify what the duty to the court will be in any given instance. Each case is different, each set of circumstances presenting their own set of challenges.

Picking up on the Court of Appeal’s analogy with prosecutorial duties, I will turn to criminal examples.

It is well-established that the prosecutor owes his or her duty to the court and not the public at large or the accused.27 The general duty is to conduct a case fairly, impartially and with a view to establishing the truth.28 On one view, the prosecutor may be seen as a lawyer with no client, but rather with sectional interests or constituencies.29 Alternatively, the prosecutor may be viewed as having a single client, the state. However, even on this view there is, in theory, an absence of conflict between the prosecutor’s duty to the court and the duty to the client because the proper administration of justice serves the interests of both.30 Nevertheless, the function of the prosecution is not free from its own difficulties and pitfalls, and this has come under scrutiny.

The High Court’s decision in Mallard v The Queen31 illustrates this in relation to the duty to disclose unused evidence. There the Court ordered the retrial of Andrew Mallard who was convicted for the murder of a Perth jeweller and imprisoned for ten years. Mr Mallard petitioned for clemency after the discovery of material in the possession of police that was not disclosed to the defence.

Previously held confidence in the relatively informal practices surrounding prosecutorial disclosure has been reduced following Mallard and a series of miscarriage of justice cases in the United Kingdom.32 However, in Mallard the High Court noted that there is authority ‘for the proposition that the prosecution must at common law also disclose all relevant evidence to an accused person, and that failure to do so may, in some circumstances, require the quashing of a guilty verdict.’33 The Court held that the prosecution in that instance had failed in its duty to reveal probative evidence to the defence.

The Victorian Court of Appeal had to grapple with a similar issue in AJ v The Queen.34 The appeal concerned the trials of AJ for various sexual offences allegedly perpetrated against XN, for which he had sustained a number of convictions. The appeal was brought on several grounds, mostly asserting error on the part of the trial judge. A second criminal matter, the matter of Pollard, was also relevant to the AJ appeal. XN was also the complainant in that matter. In the AJ appeal, two further grounds of appeal were added days prior to the appeal. The grounds were added because the applicant’s lawyers obtained additional material that demonstrated that the prosecutor in Pollard’s trial was also the prosecutor in the second and third of AJ’s trials. The material also showed that Pollard had stood trial on a number of sexual assault charges in which XN was the alleged victim, for some of which he sustained a conviction.

In the course of Pollard’s trial XN was cross-examined concerning a large number of text messages, including messages of a pornographic or sexually explicit nature, that it was alleged she had sent to the accused. In the AJ trial, XN denied sending all but one of the text messages â a denial which could have been demonstrated as false if she had been cross-examined. XN was not cross-examined on the issue in the AJ trial as counsel had no grounds for doing so.

In the Pollard trial however, the prosecutor did not herself accept XN’s denials. She conceded that the complainant had lied. In fact, defence counsel and the Crown came to an agreement about which images had been sent by XN, as it was common ground in that trial that her denials were not to be accepted as she was not a credible witness.

The court found that in the circumstances of AJ’s appeal, the prosecutor’s failure to alert trial counsel to the circumstances of Pollard’s trial and, in particular, to the fact that she (the prosecutor) did not believe XN’s denials of having sent a large number of text messages to Pollard, constituted a significant breach of her duty as a prosecutor. Had the Pollard file been disclosed to the defence lawyers prior to AJ’s trials, it would have yielded information which could potentially have been of forensic use to the applicant’s counsel. Ultimately, the court found that the conduct of the prosecution in failing to disclose that information led to a miscarriage of justice.

After the hand-down of the original judgment in AJ, the prosecutor wrote to the Court of Appeal, claiming that she had believed, at the time of the trial, that the material had been disclosed to the defence through other persons. The Court held an additional hearing and published an addendum to its original judgment.35 The Court tempered its criticism of the prosecutor, finding that a file note on the Crown file ‘could justify the prosecutor taking the view she did that appropriate disclosure had been made’. The source of the information in the file note was another barrister who briefly held the brief. However, in the Court’s view, the prosecutor should have ‘ensured that the [accused’s] lawyers were [informed of the material], if not before the trial commenced then at least when it ought to have become apparent that, as no mention of that material had been made, it was probable that they were ignorant of it’.36 The Court held that:37

where, for any reason, a prosecutor returns a brief to prosecute in a trial and the brief is subsequently delivered to another member of counsel, the duty of disclosure arises for consideration and discharge again by the new prosecutor. It is the personal responsibility of that prosecutor to ensure that that duty has been discharged prior to the commencement of the trial and as and when any further occasion calling for its exercise arises.

The prosecutorial duty to the court is an important part of the administration of justice. It is integral to the duty owed to the court and in some cases, it is for the courts to enforce. In 2010, Western Australian Chief Justice, the Hon Wayne Martin, referred a DPP lawyer to that state’s legal watchdog after his Honour declared that his failure to disclose evidence during a murder trial was a serious departure from professional standards.

The duty of defence counsel to the court is the same at a conceptual level as that of other practitioners; if counsel ‘notes an irregularity in the conduct of a criminal trial, he must take the point so that it can be remedied, instead of keeping the point up his sleeve and using it as a ground for appeal.’38

This issue was considered by the Victorian Law Reform Commission in its final report on Jury Directions.39 The Report examined obligations of defence counsel to the court and to their client in the context of the judge’s charge to the jury.40 It was noted that while the duty of counsel to raise exceptions to the charge was well established, errors that could have been dealt with by the trial judge were not being raised at trial. In fact, in more than fifty per cent of successful applications for leave to appeal against conviction in Victoria between 2004 and 2006, the grounds of appeal included issues that had not been raised at trial by defence counsel.

Whilst it is not suggested that all of these errors should have been identified by counsel, many of them should properly have been raised at the trial stage. The failure to do so has implications for the efficacy of the trial process in terms of financial inefficiencies and the emotional burden on victims and their families, witnesses and accused persons.

The AJ case demonstrates that a lawyer must always acknowledge the way in which the vulnerability of the other parties may affect his or her duty to the court. In that case, the vulnerability came from the applicant’s ignorance of the relevant information. This problem is particularly acute in litigation involving self-represented litigants. In that context, a similar trend of requiring counsel to account for the court’s duty as ‘manager’ of the litigation process is emerging. Earlier this year in the Hoe v Manningham City Council41 case , Pagone J of the Victorian Supreme Court considered an application for leave to appeal a planning decision of the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal in which the applicant was self-represented. He was not legally qualified. Throughout the proceeding, issues arose as to the applicant’s identification of a question of law which, in the words of his Honour, did not have the ‘advantage of careful consideration of a legally qualified lawyer’. The respondent’s counsel maintained that the applicant had failed to identify any error of law.

In dismissing that submission, his Honour noted that the question of law could have been ‘identified with greater elegance [but that] the initiating process [did] contain the proposition that the Tribunal’s decision contained an error in law.’ The applicant was complaining that the facts found did not fit the legal description required by the Planning Scheme in question.

The judge acknowledged that some of this applicant’s submissions appeared to take issue with the facts as found by the Tribunal, but that did not detract from the force of the principal complaint that the provisions of the Planning Scheme did not apply to the facts found by the Tribunal. The view adopted by the Associate Justice, who had refused leave to appeal, that Mr Hoe’s complaint involved no question of law was encouraged by those representing the Council.

Now, the judge did not go so far as saying that counsel breached his duty to the court, however, the observations his Honour makes about the duty to the court in the context of his case, where opposing counsel encouraged an interpretation of the applicant’s claim which ultimately did not assist the court in the exercise of its duty or to come to the correct conclusion, are worthy of note. His Honour said:42

The duties to the administration of justice of adversaries, their representatives and the Court come into sharp focus when a party is not legally represented. In such cases the duties of litigants and their representatives to the Court and the duties of the Court itself in the administration of justice require careful regard to ensure that the unrepresented litigant is neither unfairly disadvantaged nor unduly privileged. A litigant may in some cases also be expected to act as a model litigant where, for example, the litigant is the Crown, a government agency or an official exercising public functions or duties.

… The right of a litigant to have a fair and just hearing may require such assistance as diverse as listening patiently to an explanation of why something may not be given in evidence … The court’s task is “to ascertain the rights of the parties” and can ordinarily look to the legal representatives of the parties to assist it in the discharge of that task. The court relies upon the assistance it receives from the parties, and their representatives, in doing justice between them. It is, after all, the parties who have knowledge of the facts and the interest in securing an outcome. It is the parties who have the resources, in the form of evidence and knowledge, needed to be put to the court for an impartial decision to be made. Public confidence in the proper administration of justice, however, may be undermined if the courts are not seen to ensure that their decisions are reliably based in fact and law. That may require a judge to test the facts, conclusions and the submissions put against an unrepresented litigant and to “assume the burden of endeavouring to ascertain the rights of the parties which are obfuscated by their own advocacy”. It may require a judge to focus less upon the particular way in which the case is put by the parties and more precisely upon the decision which is required to be made.

At the centre of all this is the paramount duty to the court and the just, efficient and timely management of disputes, the court’s ultimate purpose. Ultimately, the following points resonate:

- Following AON v ANU, a practitioner’s duty to the court may no longer be viewed as a static obligation. A practitioner will need to factor the purpose of rules of court and procedure in the exercise of his duty to the court and to the administration of justice.

- Civil procedure reforms in Victoria and federally create obligations on all parties to litigation to adhere to a set of overarching purposes that aim to ensure the just, timely and efficient resolution of disputes. These objectives are subject to the paramount duty to the court.

- Recent case law demonstrates that in civil litigation, criminal proceedings, or proceedings involving self-represented litigants, the key aspect to retain is that the nature of a lawyer’s duty to the court will change in colour and form according to each dispute, the stage of the proceedings and the circumstances at hand at each stage of the litigation. What the court needs to achieve to deliver justice in any particular case may be a relevant consideration.

- It is critical to remember that the duty is not confined to the determination of the particular dispute at hand and may require a departure from the traditional adversarial duties of counsel and legal practitioners.

- The duty to the court is now the paramount duty on all participants in litigation, be it civil or criminal.

On that point, the passage of Richardson J of the New Zealand Court of Appeal in Moevao v Department of Labour,43 frequently cited with approval by the High Court,44 is most apt:

[T]he public interest in the due administration of justice necessarily extends to ensuring that the court’s processes are used fairly by state and citizen alike. And the due administration of justice is a continuous process, not confined to the determination of the particular case. It follows that in exercising its inherent jurisdiction the court is protecting its ability to function as a court of law in the future as in the case before it. This leads on to the second aspect of the public interest which is in the maintenance of public confidence in the administration of justice. It is contrary to the public interest to allow that confidence to be eroded by a concern that the Court’s processes may lend themselves to oppression and injustice. (emphasis added)

This really is the heart of the matter. De Jersey CJ has said extra-curially that public confidence in the judiciary and the courts, and the threat of losing it, is an important consideration for the administration of justice.45 As Brennan J observed: ‘A client â and perhaps the public â may sometimes think that the primary duty of [a lawyer] in adversary proceedings is to secure a judgment in favour of the client. Not so.’46 The foundation of a lawyer’s ethical obligation is the paramount duty owed to the court. The reasons for this are long-standing. It is the courts who enforce rights and protect the citizen against the state, who enforce the law on behalf of the state and who resolve disputes between citizens, and between citizens and the state. It is the lawyers, through the duty owed to the court, who form the legal profession and who underpin the third arm of government, the judiciary. Without the lawyers to bring the cases before the courts, who would protect the citizen? Who would enforce the law? It is this inherent characteristic of the duty to the court that distinguishes the legal profession from all other professions and trades.

Footnotes

# The paper is a merger of the speech to the Bar Association of Queensland and an earlier speech to the Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium, Melbourne, 2009, together with updating and editing.

* The author acknowledges the assistance of her associates Jordan Gray and Tiphanie Acreman.

- AON Risk Services Australia Ltd v Australian National University (2009) 239 CLR 175 (Heydon J) (‘AON v ANU’).

- [2008] VSCA 244 (‘Rees’).

- Ibid, [32].

- A Team Diamond Headquarters Pty Ltd v Main Road Property Group Pty Ltd [2009] VSCA 208.

- Ibid, [15].

- Thomas v SMP (International) Pty Ltd [2010] NSWSC 822.

- Justice Heydon, ‘Reciprocal Duties of Bench and Bar’ (2007) 81 Australian Law Journal 23, 28—29.

- Rondel v Worsley [1969] 1 AC 191, 227 (Lord Reid).

- Giannarelli v Wraith (1988) 165 CLR 543, 555.

- Ibid, 556.

- Sir Gerard Brennan, ‘Inaugural Sir Maurice Byers Lecture – Strength and Perils: The Bar at the Turn of the Century’ (Speech delivered at the New South Wales Bar Association, Sydney, 30 November 2000).

- Justice Keane ‘Access to Justice and Other Shibboleths’ (Speech presented to the Judicial College of Australia Colloquium, Melbourne, 10 October 2009).

- Victorian Law Reform Commission, Civil Justice Review, Report No 14 (2008) 154.

- Sir Anthony Mason, ‘The Independence of the Bench’ (1993) 10 Australian Bar Review 1, 9.

- Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, Review of the Criminal and Civil Justice System in Western Australia, Final Report (1999) 331.

- See for example, Chief Justice Gleeson, ‘Are the Professions Worth Keeping?’ (Speech delivered at the Greek-Australian International Legal & Medical Conference, 31 May 1999); Remarks at Opening of the Supreme and Federal Court Judges’ Conference, Auckland, 27 January 2004; The Hon Justice Michael Kirby, ‘Legal Professional Ethics in Times of Change’ (Speech delivered at the St James Ethics Centre Forum on Ethical Issues, Sydney, 23 July 1996).

- Chief Justice Spigelman, Address to the Medico-Legal Society of New South Wales Annual General Meeting (6 August 1999).

- Ronald Sackville AO, ‘Mega-Lit: Tangible consequences flow from complex case management’ 48 (2010) Law Society Journal 5, 48.

- (2009) 239 CLR 175, [27]. See also, eg, State Pollution Control Commission v Australian Iron & Steel Pty Ltd (1992) 29 NSWLR 487, 494—5 (Gleeson CJ).

- AON v ANU (2009) 239 CLR 175, fn 153.

- Eg Rule 1.14 of the Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 2005.

- Civil Procedure Act 2010 (Vic) (‘CPA’) s 8.

- CPA s 10(1)(b)-(c).

- CPA s 10(1) .

- Civil Procedure and Legal Profession Amendment Act 2011.

- [2010] NSWCA 331. The High Court has granted special leave: Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Shafron [2011] HCATrans 128.

- Cannon v Tahche (2002) 5 VR 317, [58]; see also the discussion on the role and responsibility of a prosecutor in Richardson(1974) 131 CLR 116 and R v Apostilides (1984) 154 CLR 563.

- Whitehorn v The Queen (1983) 152 CLR 657; Cannon v Tahche (2002) 5 VR 317.

- Wolfram, Modern Legal Ethics (1986) 759-60 in G E Dal Pont, Lawyers’ Professional Responsibility (3rd ed, 2006) 405.

- G E Dal Pont, Lawyers’ Professional Responsibility (3rd ed, 2006) 406.

- [2005] 224 CLR 125 (‘Mallard’); cf R v Lawless (179) 142 CLR 659.

- For example, R v Maguire (1992) 94 Cr App R 133; R v Ward [1993] 1 WLR 619. For discussion see, David Plater ‘The Development of the Prosecutor’s Role in England and Australia with Respect to its Duty of Disclosure: Partisan Advocate or Minister of Justice?’ (2006) University of Tasmania Law Review 25(2) 111.

- Mallard [2005] 224 CLR 125, 133.

- [2010] VSCA 331, superseded by [2011] VSCA 215.

- [2011] VSCA 215.

- Ibid, [38].

- Ibid, [39].

- Giannarelli v Wraith (1988) 165 CLR 543, 556 (Mason CJ).

- Victorian Law Reform Commission, Jury Directions, Report No 17 (2009).

- Ibid, 87-8.

- [2011] VSC 37.

- Ibid, [5]—[6] (citations omitted).

- [1980] 1 NZLR 464, 481.

- Jago v District Court (NSW) [1989] HCA 46; (1989) 168 CLR 23, 29-30 (Mason CJ); Williams v Spautz (1992) 174 CLR 509, 520 (Mason CJ and Dawson, Toohey and McHugh JJ).

- Chief Justice de Jersey ‘Aspects of the Evolution of the Judicial Function’ (2008) 82 Australian Law Journal 607, 609.

- Giannarelli v Wraith (1988) 165 CLR 543, 578 (Brennan J).

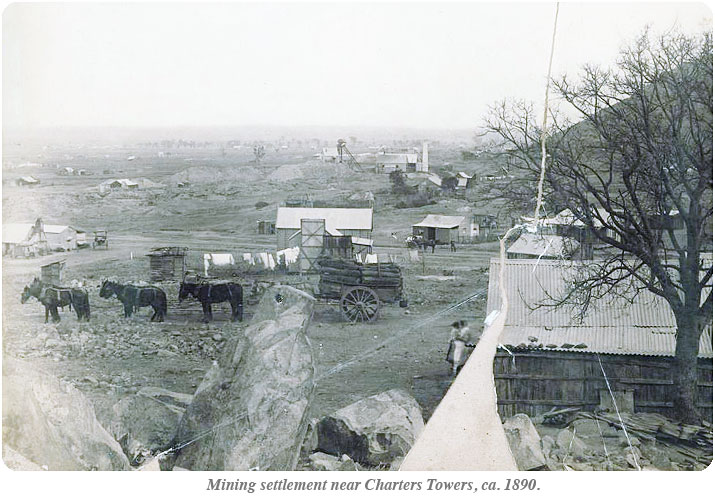

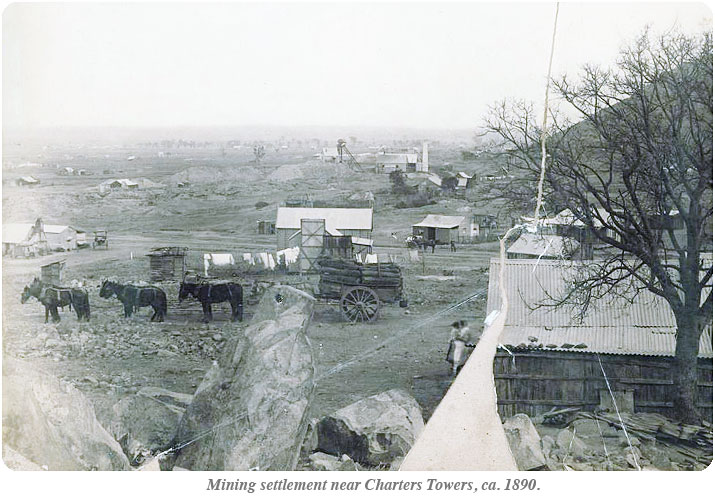

It is noted in the Log Book of H.M. Bark Endeavour that at 8 am on Thursday 8 June 1770 as the ship sailed by Great Palm Island towards Halifax Bay a criminal punishment was executed. Marine Dunster received the punishment of “a doz’n lashes” for theft. Lieutenant James Cook did not note in the Log Book whether there was a trial or whether Dunster was represented. The punishment Dunster received is probably the first record of the administration of British Justice in North Queensland.

If a plea was made for Marine Dunster then whoever made it could rightly claim to be the first advocate in North Queensland.

There are presently 22 barristers in private practice with a further 17 employed barristers in Townsville. There are five sets of Chambers, RJ Douglas Chambers, Sir George Kniepp Chambers, A.B. Paterson Chambers, Edmund Sheppard Chambers and Northern Circuit Chambers.

There are presently 22 barristers in private practice with a further 17 employed barristers in Townsville. There are five sets of Chambers, RJ Douglas Chambers, Sir George Kniepp Chambers, A.B. Paterson Chambers, Edmund Sheppard Chambers and Northern Circuit Chambers.

The North Queensland Bar Association is actively involved in the promotion of the interests of Townsville Barristers.

Barristers have been engaged to represent parties in North Queensland from the earliest days of the existence of Queensland.

In 1865, Joseph George Long Innes was appointed as a Judge of the Northern District Court. Judge Innes suffered from the immediate difficulty of not having a courthouse to sit in. His correspondence records his dissatisfaction with the lack of Court facilities. The records indicate that there were 32 criminal cases and 349 civil matters disposed of in the northern District in 1866. The Northern District extended from Gladstone north and west.

In 1865, Joseph George Long Innes was appointed as a Judge of the Northern District Court. Judge Innes suffered from the immediate difficulty of not having a courthouse to sit in. His correspondence records his dissatisfaction with the lack of Court facilities. The records indicate that there were 32 criminal cases and 349 civil matters disposed of in the northern District in 1866. The Northern District extended from Gladstone north and west.

Initially, the legal and administrative centre for Northern Queensland was Bowen.

Edmund Sheppard was appointed the first Northern Judge in 1874 and resided in Bowen.

In 1874 during the second sittings of the circuit court in Townsville Justice Sheppard sentenced an Aboriginal man known only as “Jimmy” to death for the offence of Piracy. The offence was said to have occurred on Halifax Bay, the same stretch of water where Marine Dunster was punished. The conviction was subsequently quashed on appeal.

In 1899 the Northern Supreme Court was moved from Bowen to Townsville. Between 1865 and 1899 Townsville was a circuit centre. At this time Barristers followed the Judges as they circuited.

Before 1899 there is no indication of Barristers resident in Townsville. However, in the Supreme Court Registry there is a photograph of a picnic held at Arcadia on Magnetic Island in 1908 to commemorate the transfer of Justice Chubb and the arrival of Justice Shand. In the photograph there are identified three barristers; R.J. Douglas; A.W. McNaughton and C. Jameson each of whom was to become a Justice of the Supreme Court.

In a lecture delivered by the Honourable W Carter Q.C. on 10 November 2006, “The Legal profession in North Queensland from the perspective of a former Practitioner” when referring to R. J. Douglas he said:

“In 1962 one could not identify with the Townsville Bar or with a wider North Queensland profession and not be aware of the strength and quality of the legal tradition of which one was now to become a part. The Townsville Bar had spawned R J Douglas, who after his admission in 1906 had spent a short time as associate to the Northern Judge Mr. Justice Real before commencing practice in Townsville, as Ross Johnson notes, with just five pounds in his pocket. But he practised with great success. Johnson notes this, ‘his courtroom style was very convincing. He was persistent and tenacious in defence and cross examination and fair in prosecution’.”

R. J. Douglas was the Northern Judge from 1923 to 1953, and now, almost 60 years after his retirement, his legacy lives on. His dedication to North Queensland was legendary; he set the standard for the profession to follow. As Carter QC noted that “R.J. Douglas had declined offers to leave the North for Brisbane and Johnson again notes ‘Instead, he preferred to stay in his large bungalow house at Pimlico, tending his garden, relaxing in the sun, having served North Queensland all of his life’”. R.J. Douglas’s son, James Archibald Douglas was to himself become a Supreme Court justice, as were his grandsons, Robert and James Douglas.

Fittingly, the James Cook University of North Queensland is situated in the suburb of Douglas.

On the night of Carter QC’s lecture, Dr. Dorothy Gibson-Wilde presented the Chief Justice with the North Queensland legal history database, which can be accessed on the Supreme Court website: http://www.sclqld.org.au/schp/northqld/

The gold rushes in the late 19th century had bought wealth and population to both Townsville and Rockhampton. The subsequent development of the sugar industry on the coast and grazing inland resulted in a steady economic growth prior to World War II.

There can be little doubt that the Townsville was transformed by the fact that the United States 5th Air Force was based at Garbutt for a substantial part of World War II. However, it would seem that the Bar remained stable and consistent.

Russell Skerman was admitted to the bar in 1932 and was initially the associate of R.J. Douglas. The two practised for a lengthy period of time in Townsville until he was appointed the Northern Judge in 1962.

A contemporary at the Bar in Townsville of Skerman was the redoubtable Frederick Woolonough Paterson, the only Communist ever to be elected to a Parliament in Australia, The Australian Dictionary of biography contains the following entry concerning Fred Paterson.

In December 1932 Paterson moved to Townsville where he built up a substantial, though not lucrative, criminal practice. His ingenious defence arguments entered the mythology of the left in North Queensland. From May 1937 he edited the communist newspaper, North Queensland Guardian. In 1939-44 he was an active and popular alderman of Townsville City Council. He contested Federal and State elections on every possible occasion, and, when he won the State seat of Bowen on 15 April 1944, became the first communist in Australia to be elected to parliament.

Any person who enters the Edmund Sheppard building in Townsville, the very first thing they will observe, is the dominating presence of Sir George Kneipp. His portrait hangs over the elevators, and his spirit watches over every person who enters the courts.

Alongside the 1908 photograph in the Supreme Court registry is another photograph taken in front of the old Supreme Court building, with members of the Townsville profession, marking the retirement of RJ Douglas in 1953. George Kneipp’s dominating presence is also clear in that photograph.

Sir George and all of his predecessors sat in the old Supreme Court building on Cleveland Terrace. The building overlooked Magnetic Island, Cleveland Bay, Cape Cleveland, Great Palm Island and on a very clear day glimpses of Hinchinbrook Island and the stretch of water where Marine Dunster was punished and where “Jimmy” was active.

The Old Supreme Court was a two-storey wooden building, originally built as a School of Arts. As is noted in the Queensland Heritage Register:

“Initially constructed as a Library and School of Arts in 1877, the building was one of the largest timber School of Arts buildings in Queensland. It played an important part in the social life of Townsville in the late 1870s and through the 1880s. When it was completed the hall was the premier entertainment venue in Townsville. For 86 years the building served as the only timber supreme court building in Queensland. It is also distinguished by the fact that it was a converted building, which differed from the usual practice of purpose built court houses.”

The old Court survived Cyclone Leonta in 1903 and Cyclone Althea in 1971, despite the roof being blown off on both occasions. On New Years Eve, 1965 an explosion, at the entrance to the building, destroyed the front doors .

Surprisingly, the old Magistrates Court was a sturdier building which is still standing and is now used for artistic performances.

Mr. Carter QC practiced in Townsville and was a contemporary of Sir George Kniepp and Vince Finn, the Northern Crown Prosecutor who was to be appointed to the District Court.

In 1975, the Edmund Sheppard building was opened by the then Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen. That building provided for both the Magistrates Court and the Superior Courts to be in the same complex. The building has stood the test of time, and has served the Townsville community well.

The old Supreme Court building remained unused and derelict, and despite an extensive refurbishment and plans for its future use it burned to the ground on the night of 14 April 1997.

In his lecture, Carter QC, identified 1967 as the year in which there was a significant influx of new talent to the Townsville Bar. Carter QC noted that both Kerry Cullinane and James Webb commenced practice in Townsville in 1967. They were followed shortly thereafter by Bob Greenwood, Jim Hunter, and Vic and Keith Graham.

Along with members of the private Bar Townsville has had a long history of resident Crown Prosecutors, a great number of whom had subsequently been appointed to the bench. When the District Court was reconstituted in 1959, the Northern Crown prosecutor Ralph Cormack was appointed the District Court Judge in Townsville.

There have been nine District Court Judges appointed from Townsville, including Pat Shanahan who was to eventually serve as the Chief Judge of the District Court.

Sir George Kneipp was succeeded as the northern Judge by the recently retired Kerry Cullinane QC AM. He was the first barrister to take silk outside of Brisbane.

Whenever lawyers gather and remember the past there is a very real risk that fact and legend will not coincide. We at the Townsville Bar are proud of the commitment made by barristers to North Queensland for well over 100 years.

As the experience of Marine Dunster and Jimmy shows there was a need for advocates long before there were established Courthouses in Townsville. It is a matter of some pride to the Townsville Bar that we follow in the footsteps of remarkable lawyers and continue to service that need.

Anthony W Collins

Introduction: The Lesson

The prosecutor was in trial. He was prosecuting an unlawful wounding before a North Queensland District Court jury. He was relatively experienced. He had practiced for some years and had developed a trial approach with which he was comfortable. His approach was not flashy. Just a tradesman-like eliciting of the evidence, then a straightforward application of the law to the facts. He was about to receive a lesson on the limits of that approach, and the power of narrative.

The wounding had occurred in a North Queensland Aboriginal camp known ironically as ‘Happy Valley’. That there had been a wounding was not in dispute. That it was unlawful, was. The prosecutor wanted to lead photographic evidence of the victim in hospital. The photographs were probative because they showed the slight, alcohol ravaged man who had been wounded. The white dressings on his side and shoulder blade stood out starkly on his dark skin. They graphically demonstrated the number and location of the wounds. And the photographs were not without emotional content. The prosecutor hoped to have them admitted, possibly over objection from the defence.

Defence counsel was an urbane and fatherly figure. Vastly experienced counsel. An effective advocate. He knew the power of story; the potency of narrative. He conferred with his instructing solicitor and client and announced he would not oppose the photographic evidence. The prosecutor soon found out why.

Crown counsel used the photographs that he had been so keen to get into evidence. He referred to them in his closing address. He pointed out the victim’s size and the number and location of the wounds. The evidence didn’t support self defence, he concluded.

Defence counsel used the photographs too. He held one of them up, then placed it on the visualiser. He stared up at the large image and said nothing for a moment. A touch of theatre perhaps. Then he spoke. In quiet, matter of fact tones he said something like this:

Defence counsel used the photographs too. He held one of them up, then placed it on the visualiser. He stared up at the large image and said nothing for a moment. A touch of theatre perhaps. Then he spoke. In quiet, matter of fact tones he said something like this:

‘Members of the jury, put yourselves in my client’s shoes. Imagine, if you will, sitting in the dust across from this man. It is late. After dinner. Dark. There is a pine packing crate between you. It is upturned. It serves as your makeshift table. The remains of your steak dinner is on a tin plate that sits on that crate. Your steak knife is there, along with your fork.

There is only a little light. Some from a hurricane lamp, some from the dying embers of a camp fire. Camp dogs forage and bark and there are shouts from other parts of the camp.

Imagine, that this man across from you is drunk. Very drunk and angry. He is angry with you and you have no idea why. Imagine if you will, that he stands and approaches you where you sit in the dust. Imagine that he comes quickly, closer to you. He is not a big man, as you can see, but he is standing and you are sitting. He stands above you and comes still closer. Closer to you, closer to that packing crate, closer to the plate and that steak knife. He bends as he approaches and his hand moves forward. It is a frightening prospect, isn’t it, to have this man coming at you, drunk and angry and within reach of that knife? Any wonder, that you would fear the worst and act quickly, decisively, to defend yourself as he careers into the crate and into you.’

By the time defence counsel had finished his address, the prosecutor was a little bewildered. He stared up at the photograph that he had wanted in evidence. But now he was unable to see the wounded man in the way he had before. Of course, the photograph had not changed, but then again, it had. The man in the photograph still lay in bed with wounds to his body. But now the prosecutor saw his long, wild hair matted and grimy; and his straggly beard, and his wide and dangerous eyes. It was not hard to imagine him coming at you through the darkness, intent on doing harm.

The jury must have seen the same thing, because they acquitted the accused.

Crown counsel was chastened. There was more to advocacy than knowing the facts and reciting the law. Strong storytelling, a coherent narrative can be persuasive. Decisive. The final address, and submissions in mitigation of penalty ought not be a mere rehashing of the evidence. ‘It is not a summary, witness by witness, recounting what each witness has said. … The argument is an argument, the reasoning that supports justice, the creation of the whole aura of brightness that shines down on our case.’1

The defence counsel involved was my colleague, my opponent in that trial. His closing address demonstrated many of the basic ingredients of a persuasive narrative. (I, on the other hand, had ‘choked the humanity out of the story by reducing it to its legal essentials.’)2

It was factually accurate and used language precisely. It addressed abstract legal issues in vivid, plain and simple language. The theoretical was made concrete. Concepts of self-defence, and honest and reasonable but mistaken belief, are contained within that short, simple story. It contained action and emotion. It used short words, sentences and paragraphs. It allowed the jury to see the objective facts through the eyes of the accused. It enabled them to sympathise with him, and ultimately it convinced them to acquit.

Of course, more than anything else, it contained a compelling story, consistent with the evidence and informed by his instructions.

Of course, more than anything else, it contained a compelling story, consistent with the evidence and informed by his instructions.

Finding the Story

Sometimes this is obvious. Sometimes it is right there in the facts. Compelling in its simplicity and tragedy. For example, the mother whose momentary inattention while driving, caused her unrestrained toddler to be ejected from her car. Here is the story of a mother’s distraction, then her panic; of her finding and cradling her dying child. Legally, it is relevant to sentence because of the principal of extra-curial punishment. Here that principal might be enough to shield an accused from a term of actual custody. But how bland, how emotionless, and ultimately, how ineffective might it be to invoke the principle and hand up the authorities. Surely, that sad, stark story; simply told, is of as much use and more powerful than reciting the principal and dissecting the cases.

Often though, the story is not clear. It is there somewhere in the material, in the facts, but it must be found, interpreted and told in the context of the relevant legal principles.

The well stream of the story must be your instructions. But oddly, your client may not be the best source of story. At least not without assistance. Human frailty means that clients may tell you much that is irrelevant, and omit that which is crucial. In the example of the mother given above, the grieving, guilt-ridden mother ignorant of the legal principle might never say, ‘But why should I go to jail. Surely I have suffered enough already.’ It is often up to the legal team to discover the important elements of the story: the important information about the characters and events that get to the heart of the matter.

Careful conferencing is required to maximise the chance of finding the story. How often have we found ourselves in trial when a client reveals some important matter that has been missed. ‘So and so has a grudge against me,’ or ‘that’s not what she told so and so,’ or, ‘the doctor told m e this might happen on the medication.’

e this might happen on the medication.’

Trial counsel should strive to be better story tellers. Once we are, we will have prepared the story ‘… remembering that every story has a beginning, a middle, the climax, and the end. We will be able to tell the story to the jury and support it with evidence during the trial, and put it all together again in the final argument much more effectively than [the client] will ever be able to do under fire.’3

The Value of General Knowledge

Today, more than ever, keeping abreast of popular culture and trends is crucial to finding and conveying the story. How is it possible to find the story, let alone convey it to a jury or judge, when you don’t understand the culture or the language relevant to the case.

For example, there is a resort island off Far North Queensland. That resort island is staffed by young people and frequented by young travellers. It is what has been called, a ‘party island’. A place where staff, after their shifts, are given a wrist band that entitles them to free alcoholic drinks so long as they socialise with guests. This factor, along with other matters peculiar to the island, has contributed to a number of criminal charges coming before North Queensland courts. It is simply not possible to tell a coherent story about events on this island, without coming to grips with the culture of the place.

Contemporary technologies are another important area that should be mastered if one is to tell accurate and persuasive stories about those of us who use them. Like it or not, contemporary Australians live much of their lives in and through ‘cyber space’. Not to understand that culture and communication, not to come to grips with it, not to be able to describe it and appreciate its effects, is to be deprived of half the story.

A Cautionary Approach

Two further aspects of narrative in the legal context warrant comment. The first, is that legal story telling is not like creative writing. The touchstone must be honesty and accuracy. The second is that the narrative style must be sympathetic to your jurisdiction’s legal tradition.

Advocacy styles vary. Some years ago I undertook advocacy training at the National Advocacy Centre, in Columbia, South Carolina. There, I learned a little about the American approach to trial advocacy.

It is a distinct and varied approach. However, some of what we see in popular fiction is true. American advocates do pace, gesticulate, ask rhetorical questions and strike thoughtful poses that can slow time. By comparison Australian advocates are a reserved lot, our approach (with some notable exceptions) more restrained and understated. The Australian equivalent of the theatrical flourish, is to adjust one’s wig.

It is a distinct and varied approach. However, some of what we see in popular fiction is true. American advocates do pace, gesticulate, ask rhetorical questions and strike thoughtful poses that can slow time. By comparison Australian advocates are a reserved lot, our approach (with some notable exceptions) more restrained and understated. The Australian equivalent of the theatrical flourish, is to adjust one’s wig.

The need for a cautionary approach to narrative and style was summed up by Gerald Powell:

‘While there is a strong parallel between lawsuit storytelling and storytelling as entertainment, the parallel is not exact. Like any analogy, it can be taken too far. Therefore, a word of caution is appropriate. If the jury ever comes to believe the lawyer is trying to tell a good yarn, then the effort is a total failure. The lawyer loses credibility, and the client loses the case. This methodology should not be taken too far and demands some subtlety. Thus, exaggeration, melodrama, or the use of props, dialogue, or other such overtly theatrical devices can doom the storyteller to failure. As with anything done in the court room, sincerity is the watchword.’4

The American legal profession has a long history of valuing the importance of story. And they ought to. Because in some states the art of legal narrative finds its greatest expression. If you ever doubt the value of a good story, well told, then consider this:

In America, the death penalty is available in some federal cases. As well, there is a formal process for defence counsel to try to persuade the prosecutor not to seek the death penalty. The opportunity allows experienced ‘federal capital practitioners’, to use the power of narrative to attempt to persuade the United States Attorney not to seek the death of the convicted person. So, the life story of the convicted person is told. It is a life story told, quite literally, to save a life.5

Fortunately, that possibility does not exist here. But that doesn’t mean that good narrative, well told, should not be central to our Australian legal experience.

Frank Richards

Frank Richards is a Legal Aid Queensland, in-house counsel based in Townsville. He was admitted to the bar in 1997 and has worked in private practice, for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service and the Qld DPP.

Footnotes

- Gerry Spence, Win Your Case: How to Present, Persuade, and Prevail Every Place, Every Time (2005) at 228

- Gerald R Powell, Opening Statement: The Art of Storytelling, 31 STETSON L. REV. 89(2001) at 92.

- Spence supra note 1 at 141

- Gerald R Powell, Opening Statement: The Art of Storytelling, 31 STETSON L. REV. 89(2001) at 91

- United States Department of Justice, United States Attorneys Manual s9-10.000 (2007)

Introduction

In large part, the nature of intellectual property demands the issue of damages be considered at an early stage. For example, in a case of alleged trade mark infringement, where the registered trade mark is also an ‘artistic work’ under the Copyright Act 1968, it is relevant to know that a successful copyright infringement might entitle the applicant to additional damages, whereas these are not available as relief the court may grant in a successful trade mark infringement action.1

In this article, I will consider:

- the statutory basis for damages in respect of patent, design and trade mark infringement actions;

- the two more common approaches to the calculation of damages in these areas;

- the impact, if any, of a defendant establishing an innocent infringement defence;

- additional damages;

- overseas losses, and

- personal distress.

Although not dealing with copyright as such in this article, many principles applied in relation to other IPR are distilled from the jurisprudence of copyright cases and are therefore referred to herein.

Although not dealing with copyright as such in this article, many principles applied in relation to other IPR are distilled from the jurisprudence of copyright cases and are therefore referred to herein.

The relevant provisions

The Federal Court and the prescribed courts have power to grant in an action for an infringement of patent,2 trade mark3 and plant breeder’s rights,4 an injunction (subject to such terms, if any, as the court thinks fit) and either damages or an account of profits at the option of the applicant.

The nature of these damages

The infringement of a patent, design or trade mark is a tort. Proof of damage is not essential for the establishment of the action and the action therefore accrues at the date when the infringing act took place rather than when the applicant suffers loss.5

Damages are compensatory in nature. The measure of damages is the loss in value caused by the infringement of the copyright for example, as a chose in action6 or the amount by which the incorporeal right has been depreciated.7 Similarly expressed, the Full Court considered that ‘the purpose of an award of damages for breach of copyright “is to compensate the plaintiff for the loss which he has suffered as a result of the defendant’s breach”’.8

Usual approaches

The defendant is liable for all loss which is actually sustained by the plaintiffs as a natural and direct consequence of the unlawful acts of the defendant.9 Although there is no fixed method, the courts usually apply one of two approaches of assessing compensatory damages: the ‘loss of sales’ approach or the ‘licence fee’ approach.10

Loss of sales approach

A difficulty with this approach lies with the establishment of a case that rests solely upon the footing that a sale by the respondent is a lost sale by the applicant.

The mere use of a deceptively similar trade mark in respect of services of the same description for example will not raise for the court an inference that the custom acquired by the infringer would have been attributed to the applicant.11

In Elwood, the applicant sought compensatory damages applying a lost sales method in respect of two T-shirt designs.12 Elwood’s application was dismissed by the primary judge, but the appeal to the Full Court was allowed.13 In the hearing on quantum, referred back to the primary judge, Elwood sought to base its damages claim by taking an average of its sales figures and then making the assumption that if the respondent was not in the market, it would have continued to sell that average number of T-shirts each month extrapolated over the ensuing 3 years.

Gordon J rejected this approach in the case, on the basis that the facts did not support the contention of probable sales.

In this regard, her Honour said the T-shirt was an update of an Elwood design first run in 2005. Gordon J noted that the earlier T-shirt design itself only ran for 18 months, making it unrealistic to claim damages on the basis the T-shirt had a further 3 years of market life.

Notwithstanding, her Honour identified the following steps:

- Assume respondent sought applicant’s market share;

- Assume respondent’s sales = applicant’s lost sales;

- Discount preceding assumption to show not all sales would have been the applicant’s sales;

- Discount unit sales by the facts of the case.14

In Elwood, Gordon noted that there was no evidence, expert or otherwise which assisted in determining an appropriate discount factor. There was also no evidence to identify who was the market leader. There was however a starting point, the number of units sold and the price of each unit.15

Gordon J observed that even if the parties were selling to similar markets and at similar prices, it had been found that the applicant had failed to put forward sufficient evidence for the court to draw an inference as to whether some or all of the sales made by the respondent could be properly characterised as sales lost by the applicant.16

Some degree of speculation is expected in the court calculating compensatory damages: Norm Engineering at [295] ; Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v DAP Services (Kempsey) Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 40 ; (2007) 157 FCR 564 at [35] . However the court may take into account the failure of the applicant to assist by providing proper sales data and relying solely on the proposition that the respondent’s sales equated to the applicant’s losses.

Some care must be taken in confusing the concepts behind the ‘lost profit’ or ‘lost sales’ approach and the alternative to damages, and ‘account of profits’.

In Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Vidtech Gaming Services Pty Ltd (2006) 68 IPR 229 the primary judge considered that he lacked the evidence necessary to compute damages referrable to the applicant’s loss.17 His Honour proceeded to assess damages based on the respondent’s net gain, which the Full Court said was impermissible, as the applicant elected damages not an account of profits.18

The applicant in Aristocrat could have but did not contend that it lost some proportion of the sales made by the respondent, which would otherwise have been made by the applicant.19 The applicant’s case was based solely on the contention that it lost 400 units in sales which was not supported by the evidence.20