There have been a number of appellate decisions in coronial law in the past twelve months. Although none of these decisions change the law in any way that is likely to be of significance to the practical conduct of coronial proceedings, the authorities do contain helpful statements of relevant principles and useful examples of the application of those principles.

The cases are grouped into the following topics:

- Cases concerning the decision to hold an inquest;

- Findings and procedural fairness;

- Referral of information to prosecuting authorities;

- Non-publication orders; and

- Decisions concerning autopsies.

Finally, this paper also considers the recent decision of the High Court in Burns v The Queen [2012] HCA 35, which concerns the question of whether a supplier of drugs may be guilty of manslaughter in circumstances where the purchaser of the drugs dies of a drug overdose in the supplier’s presence.

Although the decision in Burns does not concern coroners or coronial proceedings, it is important to coroners in jurisdictions where the coroner is obliged to forward information to prosecuting authorities where the coroner is of the view that a person has committed an indictable offence.

Cases concerning the decision to hold an inquest

There have been three recent appellate decisions concerning the decision to hold an inquest: Conway v NSW State Coroner [2011] NSWCA 319 (28 September 2011); Irfani v State Coroner [2011] WASC 270 (3 October 2011); and Taing and Nuoin v The Territory Coroner [2011] NTSC 58 (9 August 2011).

Conway concerned a decision of the State Coroner refusing to hold an inquest into the death of M, a 15 year old young person who died in a motor vehicle accident in Sydney in 2003. At the time, M was homeless. The vehicle in question was stolen and was driven by a young man who was providing M with accommodation at the time. M’s death had been thoroughly investigated by NSW police. However, M’s mother had ongoing concerns about the manner of her death, and sought that an inquest be held to investigate, inter alia, whether the Department of Community Services (“DOCS”) could have done more to assist M find accommodation.

The State Coroner refused to hold an inquest, indicating that the manner and cause of M’s death was sufficiently disclosed, and that an inquiry into M’s relationship with DOCS was too remote from the manner and cause of M’s death. Justice Barr agreed with this decision: Conway v Jerram [2010] NSWSC 371. M’s mother sought leave to appeal from the decision of Barr J. Leave was refused by the Court of Appeal on 28 September 2001.

In refusing leave to appeal Young JA commented that a coroner has a “wide, but not unlimited, mandate to hold or not hold an inquest concerning the death of a person” (at [47]). At para [49], his Honour observed that “in the usual cases of death, a line must be drawn at some point beyond which, even if relevant, factors which come to light will be considered too remote from the death.”

Taing and Nuong concerned a decision of the NT Supreme Court relating to a decision of the NT Deputy Coroner refusing to hold an inquest into the deaths of two fishermen who died in a fire at their campsite. As with the death in the Conway case, there had been an extensive police investigation into the deaths.

In the Supreme Court, Blokland J accepted that it would be “desirable” to hold an inquest if there were some “practical benefit to the next of kin in terms of better understanding … what occurred to the deceased, or that there be a benefit to the general public, a section of it, or to the overall administration of justice” (at [54]). Justice Blokland emphasised, however, that “[a]n inquest should not be held where it would clearly be a futile exercise.” (at [54] and [56])

Justice Blokland accepted that a “comprehensive” investigation had been conducted by police (at [65]). In these circumstances, her Honour stated that “[w]ithout pointing to any further evidence or how an inquest would reveal such evidence it has not been demonstrated that an inquest into the deaths of the deceased would serve any useful purpose.” For these reasons, Blokland J declined to order that an inquest be held.

Irfani concerned a decision of the WA State Coroner refusing to hold an inquest into the death of Fatima Irfani. Ms Irfani died in a Western Australian hospital in 2003. She had arrived at Christmas Island as a refugee in 2002. She suffered from hypertension and hepatitis C. In January 2003, whilst in detention, she complained of severe headaches over a number of days. Around noon on 15 January 2003, Ms Irfani collapsed. She was initially taken to the Christmas Island hospital, but was later that day flown to Perth in a critical condition. A head CT scan showed that she had a intra-cranial haemorrhage. Surgery was performed. However, her condition deteriorated, and she died on 19 January 2003.

Ms Irfani’s family sought that an inquest be held into her death. The issues to be raised in the inquest concerned the care and treatment provided to Ms Irfani in detention at Christmas Island and the timing of her transfer to Perth. No issues were raised as to the care and treatment provided to Ms Irfani after the transfer to the Perth Hospital.

A coroner in Western Australia declined to hold an inquest. Ms Irfani’s family sought an order from the Supreme Court requiring an inquest to be held.

As Ms Irfani was not “in care” at the time of her death, an inquest was not mandatory. However, Ms Irfani’s family argued that because Ms Irfani was in immigration detention, the death was analogous to a death in custody.

Justice McKechnie in the Supreme Court in Western Australia accepted that there is a public interest in holding a public inquiry into deaths occurring in immigration detention (at [37]). However, his Honour also observed that “the ultimate purpose of the Coroner is to inquire into a particular death.” (at [37]). His Honour expressed the view that the circumstances of the particular death, “being well documented” would not lead to the “wider inquiry sought by the plaintiffs.” (at [37]). Justice McKechnie emphasised that “the focus of an inquest is into the death and the immediate circumstances giving rise to the death. It is not a general inquisition into the detention system.” (at [43]) In this regard, his Honour observed that two independent experts briefed by the Coroner had concluded that the standard of the medical response on Christmas Island was reasonable, subject to one exception. That one exception was the administration of a drug, however, there was no evidence that that drug was in fact administered or that it had anything to do with Ms Irfani’s death.

Justice McKechnie also observed that there had been a lengthy delay from the date of the death to the date that the Supreme Court was asked to order that an inquest be held (at [40]). Whilst such a delay is not a barrier to an inquest being held, it is “one of the relevant facts to be taken into account.” (at [40])

His Honour observed that the Coroner had undertaken an investigation and would make findings. His Honour stated that he was “unpersuaded that a formal inquest as part of this investigation [would] sufficiently advance the Coroner’s knowledge in this case in the interests of justice.” (at [47])

Comment: It may be observed that there are a number of themes that recur in the above three decisions. First, the decisions confirm the width of the coroner’s discretion as to whether or not to hold an inquest. The decisions (particularly Conway and Irfani) also confirm that the starting point when determining whether or not to hold an inquest is the coroner’s statutory duty to determine the date, place, cause and circumstances (or manner) of death. Finally, the decisions confirm the importance of a thorough police investigation as part of the coronial process. It may not be necessary to hold a public hearing where there has been a thorough investigation, and it appears from that investigation that a public inquest will not shed any further light on the date, place, cause and circumstances of the death.

Findings and procedural fairness

Onuma v Coroner’s Court of South Australia [2011] SASC 218 (9 December 2011) is an interesting decision of the Supreme Court of South Australia, which provides guidance to coroners on questions of procedural fairness.

Onuma concerned an inquest into the deaths of two elderly women who each died following surgery for a vaginal prolapse. The same surgeon performed the procedure in each case. Both women suffered from a perforated bowel that was caused at some stage during their respective surgical procedures.

At the conclusion of the inquest, the Deputy Coroner made findings. In those findings, the Deputy Coroner was critical of the competence of the surgeon who performed the surgeries in question. The Deputy Coroner also made recommendations to the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists concerning the competence of surgeons performing vaginal prolapse surgery.

The surgeon in question appealed the Deputy Coroner’s findings.

The grounds of appeal in the Supreme Court included complaints about the findings made by the Deputy Coroner, the comments made by the Deputy Coroner, the recommendations made by the Coroner and a complaint about a denial of procedural fairness.

The complaint about the formal findings related only to one of the deceased — Mrs Hillman. The Deputy Coroner found Mrs Hillman’s cause of death to be “hypoxic ischaemic brain injury due to an intracerebral and subdural haemorrhage as a consequence of anticoagulation given to treat a left subclavian vein thrombosis and pulmonary thomboemoli, and peritonitis following perforation of the small bowel during surgery for vaginal prolapse.” (at para [25])

In considering this ground, Kelly J emphasised the distinction between findings as to the “cause” and “circumstances” of a death, and observed that the coroner has an “obligation to inquire into all of the facts which may have operated to cause the death of the deceased and as well to inquire into the wider circumstances surrounding the death of the deceased”. Justice Kelly concluded that the Deputy Coroner was required to set out the case and circumstances of Mrs Hillman’s death, “which necessarily included the unfortunate and catastrophic series of post-operative complications described in the reports…” (at para [40])

Justice Kelly acknowledged that these matters were traversed in the “Findings of Inquest”. However, her Honour found that these matters should have been included in the express finding which the Deputy Coroner made about the cause of death (at para [42]).

The appellant also complained about particular comments made by the Deputy Coroner concerning the appellant’s lack of competence. Justice Kelly held that the comments were not supported by the evidence, observing that it was difficult to say that “something has been done incorrectly or wrongly on the basis of one-off, or two-off, events.” (para [58])

However, although her Honour found that the Deputy Coroner should not have commented that the surgeon lacked competence, the Court declined to make a finding that the Deputy Coroner should have found that the appellant was appropriately qualified and did possess the necessary skill and competence. In the Court’s view, there was insufficient evidence before the Coroner to justify a finding on this topic one way or another.

As to the complaints about the recommendations, Kelly J disagreed with the appellant’s submission that the recommendations were based solely on the impugned comments, observing that the expert evidence did provide a proper basis for the recommendations. However, her Honour also held that the Supreme Court did not have jurisdiction to set aside recommendations. In her Honour’s view, recommendations were not part of the statutory “findings” which are subject to an appeal under s. 27(1) of the Coroners Act 2003 (SA). In this regard, her Honour disagreed with the decision of Debelle J in Saraf v Johns (2008) 101 SASR 87.

The final complaint related to an allegation that the appellant had been denied procedural fairness because the Deputy Coroner made comments concerning his competence without first advising him of the Coroner’s intent to make such comments. In rejecting this ground, Kelly J commented that there was “no doubt” that a Coroner is subject to rules of natural justice and fairness, and that those rules “require that any party likely to be affected, either directly or indirectly, by a decision is to be given the opportunity to be heard and to make submissions before any decision is made”. (at [95])

However, her Honour observed that Counsel Assisting had asked (over objection) a number of questions of the appellant and relevant experts relating to the appellant’s competence. Moreover, Counsel Assisting had specifically raised the topic of the appellant’s competence in closing submissions, and counsel for the appellant had had a right to reply to these submissions. In view of these matters, Kelly J concluded that the Deputy Coroner had complied with his duty to afford procedural fairness.

In Danne v the Coroner [2012] VSC 454, a surgeon who was a party to an inquest sought access to a postmortem CT scan and tissue samples. The Coroner granted access, conditional on the surgeon providing the Coroner with copies of any expert reports subsequently prepared concerning this evidence.

The Supreme Court of Victoria set aside the Coroner’s order. The Court held that the Coroner had erroneously sourced the power to make the condition as being an aspect of the coronial jurisdiction over the body of the deceased. The Court held that, once removed, tissue samples are no longer part of the body. The Court also held that the condition breached the coroner’s duty to afford natural justice, and that the condition was inconsistent with legal professional privilege.

Referral of information to prosecuting authorities

In Nona and Ahmat v Barnes [2012] QSC 35 (29 February 2012), the appellants sought review of a decision of the Queensland State Coroner refusing to refer information to the Director of Public Prosecutions (“DPP”) pursuant to s. 48(2) of the Coroners Act 2003 (Qld). In particular, the appellants sought an order that the State Coroner provide a “statement of reasons” pursuant to the Judicial Review Act 1991 (Qld).

The Supreme Court of Queensland dismissed the application, finding that the decision of the State Coroner refusing to refer the information was not a “reviewable decision” under the Judicial Review Act because it did not “confer, alter or affect legal rights or obligations”.

Non-publication orders

Bissett v Deputy State Coroner [2011] NSWSC 1182 (7 October 2011) concerned an inquest held in New South Wales involving a police shooting of a mentally ill man, Adam Salter. A critical incident investigation was held, and in the course of that investigation, a “walk through” interview was conducted between investigating officers and Sergeant Bissett, the police officer who had shot and killed Mr Salter. The walk-through interview was recorded on DVD.

A critical issue in the inquest was whether Sergeant Bissett had shot the deceased in self defence or in defence of other police officers. Some of Sergeant Bissett’s answers in the DVD were exculpatory, and some of her answers were incriminatory.

The DVD was admitted into evidence (over objection) and the ABC made an application for access to it. The Deputy State Coroner granted access, but imposed a short non-publication order to enable Sergeant Bissett to approach the Supreme Court to seek an injunction prohibiting the Coroner from providing the DVD to the media.

Justice Hulme held that it was appropriate for the transcripts of the DVD to be published, but that, until further order, there should be no publication of the DVD “walk through” itself. Justice Hulme took into account that there was a real possibility that the Deputy State Coroner would refer the matter to the DPP and that Sergeant Bissett may be charged with a serious criminal offence. His Honour also took into account the fact that there was a substantial possibility that the DVD walkthrough would not be admitted in any trial. In these circumstances, publication of the DVD could jeopardise any future trial.

Justice Hulme distinguished the DVD from the publication of other evidence before the coroner, including the transcript of the DVD, stating “in its inherent nature, it will be appreciated not simply by one sense, but by two — hearing and sight.” (at [25]) Because of this, his Honour considered that the DVD was more likely to be remembered than a mere publication of the transcript.

In these circumstances, his Honour accordingly concluded that the publication of the contents of the DVD was liable to prejudice the proper administration of justice and that publication should thus be restrained: at [27]. However, his Honour also held that permanent prohibition of publication of the DVD was not required, and that publication should only be delayed until it became apparent that no trial of the Sergeant Bissett was likely in the foreseeable future, or that any such trial had been held.

Note: In Bissett, the Court erroneously applied the Courts Suppression and Non-Publication Orders Act 2010 (NSW), which does not apply to coronial proceedings. The appropriate legislation was s. 74 of the Coroners Act 2004. However, the principles which Hulme J applied would appear to be of general application.

It may also be of interest to note that the Bissett inquest led to a Police Integrity Commission Inquiry which was held this year into the conduct of the critical incident investigators. The decision of the Inquiry is pending.

Decisions concerning autopsies

There are two recent decisions of the Northern Territory Supreme Court concerning autopsies: Evans v Northern Territory Coroner [2011] NTSC 100 (6 December 2011) and Raymond- Hewitt v Northern Territory Coroner [2011] NTSC 94 (22 November 2011).

Evans and Raymond-Hewitt each concerned the question of whether an autopsy should be ordered in circumstances where the deceased were indigenous persons, and where the family of the deceased strongly objected to the autopsy on spiritual grounds.

Evans concerned a young baby who had died in his sleep. The likely cause of death was SIDS. Raymond-Hewitt concerned an indigenous man who had died in a road accident when his four wheel drive collided with a Mack Truck on the Arnhem Highway.

In both cases, the Supreme Court directed that no autopsy be held. In reaching these determinations. the Supreme Court in both cases emphasised that there was no suggestion of foul play. The Court observed in both cases that there was a public interest in making an accurate finding as to the cause of death, but also observed in both cases that it was relatively unlikely that an autopsy would shed any further light on the cause of death.

Comment: The above cases illustrate that genuinely held spiritual beliefs of the family of the deceased will often override the public interest in accurately determining the cause of death, particularly where there is little likelihood of an autopsy shedding any further light on the cause of death unless there is any suspicion of foul play, in which event, spiritual concerns will take second place to the public interest in investigating those suspicions.

Criminal law decision: manslaughter for death resulting from a drug supply

Burns v The Queen concerns the liability of an accused for manslaughter arising out a drug supply. The facts, briefly stated, were as follows. The appellant and her husband jointly supplied the deceased with methadone. The deceased injected the methadone within the appellant’s apartment, but it was not clear whether the appellant assisted the deceased with the administration of the drug.

The deceased remained in the apartment for a period of time after injecting the methadone. The appellant told the deceased that had to leave. The appellant’s husband assisted the deceased to leave the apartment. The following day, the deceased’s body was found in a toilet block in the yard of the appellant’s apartment. A forensic pathologist gave evidence that the deceased died from a combination of the methadone and a prescribed drug which the deceased had taken earlier.

The appellant and her husband were each charged and were each convicted of manslaughter. The appellant’s husband died in custody without any appeal to his conviction. The appellant appealed her conviction, first to the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal, and then to the High Court.

In the High Court, the prosecution relied on two alternate bases for sustaining the conviction of manslaughter: namely, manslaughter by unlawful and dangerous act and manslaughter by criminal negligence. By a majority, the High Court held that the conviction for manslaughter could not be sustained on either basis. In dissent, Heydon J expressed the view that a conviction for manslaughter by unlawful and dangerous act was available.

Manslaughter by unlawful and dangerous act: In the High Court, the Crown conceded that the act of supply could not, of itself, sustain a conviction for manslaughter by unlawful and dangerous act. Every member of the High Court accepted that this was a proper concession.

All members of the High Court accepted that the supply of an illicit drug is unlawful, however, they held that the supply of a drug is not dangerous. The Court explained that supplying an illicit drug is not dangerous because illicit drugs are not dangerous in and of themselves. Rather, illicit drugs are only dangerous if they are consumed. In this regard, the Court stated that the voluntary act of the deceased in consuming the methadone broke the chain of causation, so that it could not be said that the appellant had, in supplying the methadone, “caused” the deceased’s death.

Although the Crown had conceded that the act of supply was not sufficient of itself to sustain a conviction for manslaughter by unlawful and dangerous act, the Crown sought to maintain the conviction on the basis that the appellant, acting in concert with her husband, had assisted in the administration of the drug to the deceased.

The majority did not decide whether assisting in the administration of an illicit drug could sustain a conviction for manslaughter by unlawful and dangerous act. Rather, the majority found that there was insufficient evidence for the Crown to establish that the appellant had, in fact, assisted in the administration of the drug. Justice Heydon dissented on this point — his Honour would have ordered a retrial on the basis that there was sufficient evidence for a jury to find that the appellant had assisted in the administration of the drug.

Manslaughter by criminal negligence: In order to sustain a charge of manslaughter by criminal negligence, the Crown must first establish that there was a duty between the accused and the deceased which required the accused to act.

All members of the Court held that the relationship between a supplier of drugs and the purchaser of drugs did not give rise to any relevant duty. In making this finding, the Court emphasised again that the appellants’ actions in supplying drugs to the deceased did not “imperil” his life — rather “the imperilment of the deceased was the result of his act in taking the methadone.” (at [105])

In the circumstances of this case, the Court determined that there was no relationship between the appellant and the deceased which would have required the appellant to obtain medical assistance for him.

Belinda Baker

Footnote

- The views in this paper are those of the author’s and should not be taken to represent the views of the NSW Crown Solicitor.

A historical note

If we were to delve into history2, we would discover that the English common law system originally required that estates in fee simple and in fee tail general be bequeathed to the eldest son of the testator, with all other children being excluded; however, it was possible even in the earliest common law times to deprive an heir by inter vivos transfer.3 After The Statute of Wills was passed in 1540, a testator could also deprive his heir by will4 and after 1646 all children could be deprived of land inheritance. Widows were protected by the law of dower, which allowed a widow the use for her life of one-third of her husband’s real property, and widowers by curtesy, which allowed a widower with a child of the marriage the use for life of all of his wife’s land. Neither dower nor curtesy could be defeated by will or by inter vivos transfer.

As to personal property, at common law, all of a wife’s personal property passed to her widower absolutely, unless he consented to a different disposition in her will, or by inter vivos transfer. A deceased husband’s personal property was subject to forced (fixed) shares. A surviving wife was entitled to half of her deceased husband’s net personal property by forced share where there were no children of the marriage. This rule also applied where there were surviving children but no widow. The remaining half of the personal property could be left by will as the testator pleased. Where a wife and children survived, the wife was entitled to a one-third forced share, and the children to a one-third forced share, with the remainder to be disposed of by will as the testator wished.5 Forced

shares were first recognised in 1215,6 but had largely fallen out of use in England by 1400, in Wales by 1696, and were completely abandoned in all areas of England in 1724.7

As the 19th century progressed, the idea of testamentary independence became more embedded in the common law. The Dower Act 1833 (UK) allowed a husband to overturn his wife’s dower by will or by inter vivos transfer. In the absence of forced shares, this allowed husbands to leave their entire estates away from their widows and children if they so wished. After the Married Women’s Property Act 1882 (UK), wives could likewise leave all their property away from their widowers and children.

As the 19th century progressed, the idea of testamentary independence became more embedded in the common law. The Dower Act 1833 (UK) allowed a husband to overturn his wife’s dower by will or by inter vivos transfer. In the absence of forced shares, this allowed husbands to leave their entire estates away from their widows and children if they so wished. After the Married Women’s Property Act 1882 (UK), wives could likewise leave all their property away from their widowers and children.

The modern forced share approach can be contrasted with that of statutes in a small group of common law countries which give a wide discretion to the Courts to divide an estate under dispute, commonly referred to as either family or dependants’ provision or testator’s family maintenance.

The notion of total testamentary freedom was a construct of the nineteenth century, an offshoot of the style of English laissez-faire liberalism that was fashionable at the time. However, it was recognised late in the nineteenth century that testamentary freedom of this type allowed some testators to ignore their responsibilities to close family, particularly spouses and children. This a problem in the then newly developing, but wealthy, dominions of Australia, New Zealand and Canada, and was fanned by an indignant press which reported several notorious cases of wealthy men dying and leaving their widows and children unprovided for.8

Our Family Provision legislation originated from New Zealand legislation, the Testator’s Family Maintenance Act 1900, thought to be innovative and which attracted much attention in the common law world at the time. It was copied for both testate and intestate situations in English law, and the provinces of Canada (other than Quebec). It actually had its genesis in an 1877 Act which enabled illegitimate children under 14 to apply for maintenance out of the estate of deceased parents, the Destitute Persons Act 1894 (NZ), and the Native Land Court Act 1894 (NZ) which provided that Maori applicants were to be left with ‘sufficient land for their maintenance’ after claims alienating Maori land reserves to white settlers.

The 1900 Act was replaced by the Testator’s Family Maintenance Act 1906, which extended the time period for applications from six months to twelve months from the date of probate, and allowed for provision to be made in the form of either lump sums or periodical payments. This Act was in turn repealed and replaced by the Family Protection Act 1908 and the idea of family provision quickly spread throughout Australia, and eventually to Canada and the UK.

Queensland Legislation

In Queensland, Family Provision legislation confers rights on applicants, typically spouses, de facto spouses, children (including adopted and stepchildren) and specifically defined dependants9 to apply to the court to overturn bequests in wills which do not adequately provide for the maintenance and support of the applicants. This is clearly an interference with testamentary freedom, and is supported by both legislation and the courts on public policy grounds.

The relevant section of the Queensland legislation is s. 41:

(1) If any person (the deceased person) dies whether testate or intestate and in terms of the will or as a result of the intestacy adequate provision is not made from the estate for the proper maintenance and support of the deceased person’s spouse, child or dependant, the court may, in its discretion, on application by or on behalf of the said spouse, child or dependant, order that such provision as the court thinks fit shall be made out of the estate of the deceased person for such spouse, child or dependant.

…………

(8) Unless the court otherwise directs, no application shall be heard by the court at the instance of a party claiming the benefit of this part unless the proceedings for such application be instituted within 9 months after the death of the deceased; but the court may at its discretion hear and determine an application under this part although a grant has not been made.

An often cited statement of basic principle underlying this legislation is that of Salmond J in In re Allen (deceased), Allen v Manchester:

‘The provision which the Court may properly make in default of testamentary provision is that which a just and wise father would have thought it his moral duty to make in the interests of his widow and children had he been fully aware of all the relevant circumstances.’

It was adopted by the Privy Council in a New South Wales appeal in Bosch v Perpetual Trustee Co. That case, in turn, has been followed and applied many times.

In McCosker v McCosker, Dixon CJ and Williams J, referring to what is sometimes called the primary or jurisdictional question, said:

“The question is whether, in all the circumstances of the case, it can be said that the respondent has been left by the testator without adequate provision for his proper maintenance, education and advancement in life. As the Privy Council said in Bosch v Perpetual Trustee Co (Ltd) the word ‘proper’ in this collocation of words is of considerable importance. It means ‘proper’ in all the circumstances of the case, so that the question whether a widow or child of a testator has been left without adequate provision for his or her proper maintenance, education or advancement in life must be considered in the light of all the competing claims upon the bounty of the testator and their relative urgency, the standard of living his family enjoyed in his lifetime, in the case of a child his or her need of education or of assistance in some chosen occupation and the testator’s ability to meet such claims having regard to the size of his fortune. If the court considers that there has been a breach by a testator of his duty as a wise and just husband or father to make adequate provision for the proper maintenance education or advancement in life of the applicant, having regard to all these circumstances, the court has jurisdiction to remedy the breach and for that purpose to modify the testator’s testamentary dispositions to the necessary extent.”10

Singer v Berghouse

In 1994, in Singer v. Berghouse,11 the High Court made the authoritive re-statement of the approach largely adhered to by the court when considering Family Provision applications. The majority of that court made the following comments:

“In Australia it has been accepted that the correct approach to be taken by a court invested with jurisdiction under the legislation of which Act (Family Provision Act) (NSW)) is an example that was stated by Salmon J. [Re Allan v. Manchester (1921) 41 NZLR 218]. In that case His Honour said (at 220-221):

‘The provision which the court may properly make in default of testamentary provision is that which a just and wise father would have thought it his moral duty to make in the interests of his widow and children had he been fully aware of all the relevant circumstances’

For our part we doubt that this statement provides useful assistance in elucidating the statutory provisions. Indeed references to “moral duty” or “moral obligation” may well be understood as amounting to a gloss on the statutory language”.

It is true that the Act is silent in respect of the terms “moral obligation” or “moral duty”. The jurisdiction of the court is invoked only when, by the terms of Section 41(1) is satisfied, as a matter of exercise of its discretion, that adequate provision is not made from the estate for the proper maintenance and support of, in this case, the adult son of the deceased.

Singer, however, had its detractors. For example, in the Victorian Court of Appeal, Callaway JA took a different view when he said:

Singer, however, had its detractors. For example, in the Victorian Court of Appeal, Callaway JA took a different view when he said:

“[I]t is one of the freedoms that shape our society, and an important human right, that a person should be free to dispose of his or her property as he or she thinks fit. Rights and freedoms must of course be exercised and enjoyed conformably with the rights and freedoms of others, but there is no equity, as it were, to interfere with a testator’s dispositions unless he or she has abused that right. To do so is to assume a power to take property from the intended object of the testator’s bounty and give it to someone else. In conferring a discretion in the wide terms found in s.91, the legislature intended it to be exercised in a principled way”.12

Grey was cited13 for the proposition that the jurisdictional pre-condition stated as part of the two-stage test in Singer’s case could not be made out unless the court was satisfied the deceased had failed, by his will, to fulfill his moral duty to a younger son. The same sentiments were expressed by McDonald J in Coombes v Ward14 and the same path was been followed by Judges in Tasmania15 and Western Australia.16

Such a trend to debate the correctness of reliance on what was said in Singer can hardly be said to have extended to judicial writings in Queensland although in Chapman v. Chapman17 Cullinane J made it clear that, in his view, moral claim and moral duty, remain relevant.

He said:

“the appellant accepted His Honour’s finding that the deceased owed a moral duty to the respondent which had not been satisfied by their bequest ..… on the other hand the moral claim of the appellant was a very strong one”.

Almost exactly ten years ago, at a QLS Succession Law Conference (now) Justice Alan Wilson in further developing a paper he had delivered at an earlier, carefully examined these cases and other academic writings to show that the High Court’s dictum was wrong in that “it ignored the historical, societal and philosophic underpinnings upon which the remedy was constructed”.

What is clear is that, by its terms, Section 41 of the Succession Act is designed to protect eligible persons where inadequate provision (or no testamentary provision) is made for their proper maintenance and support in life. Singer goes no further than this with what has become known as the ‘two stage process’.18

There is a threshold test. An applicant must show that he has a prima facie case that adequate provision has not been made. This is reflected in the Practice Direction.19

The need for the applicant to establish a moral claim to further provision became a matter of judicial debate and has clearly been endorsed as a useful perspective from which to assess the statutory criteria. Gleeson CJ said in Vigolo v Bostin:

“In explaining the purpose of testator’s family maintenance legislation, and making the value judgments required by the legislation, courts have found considerations of moral claims and moral duty to be valuable currency. It remains of value, and should not be discarded. Such considerations have a proper place in the exposition of the legislative purpose, and in the understanding and application of the statutory text. They are useful as a guide to the meaning of the statute. They are not meant to be a substitute for the text. They connect the general but value-laden language of the statute to the community standards which give it practical meaning. In some respects, those standards change and develop over time. There is no reason to deny to them the description “moral”. As McLachlin J pointed out in the Supreme Court of Canada, that is the way in which courts have traditionally described them. Attempts to misapply judicial authority, whatever form they take, can be identified and resisted. There is no occasion to reject the insights contained in such authority.”20

In Vigolo, a claim was made by an adult son who had worked for 20 years on his father’s farm. The stated inducement was that the son would receive the farm upon the father’s death. However, some years prior to the father’s death, there was a dispute between father and son, resolved by a Deed of Settlement entered into at arms length and on commercial terms. At the time of the father’s death, no provision had been made for the son who sought further provision under the relevant statute.

The claim was not put on the basis of the applicant’s need because he was quite well off and in a much better financial position than his siblings. However the claim was put purely on the basis that the deceased had a moral obligation to the applicant bearing in mind his prior work in the family farming enterprise and promises (relating to the farm) made to him during the currency of that enterprise.

In essence, in the judgment of Gleeson CJ and the joint judgment of Heydon and Callinan JJ, the secure financial position of the applicant was not determinative of the issue. Gleeson CJ noted that the fact that the applicant had been financially advantaged by his father (by being included in the farming enterprise) and had been adequately compensated for his extensive efforts upon dissolution of that enterprise was “significant”. Heydon and Callinan JJ held that adequacy of provision was not to be assessed simply in light of whether the applicant had the independent means to live comfortably, but was to be assessed in all of the circumstances, including promises of the kind made to the applicant and the circumstances in which those promises were made. Gummow and Hayne JJ also appeared to consider the promises significant.

Taken as a whole, the judgment appears to contemplate that applicants may succeed on a claim even if they have more than sufficient resources of their own, on the basis that all relevant factors must be balanced to arrive at a conclusion as to whether “adequate” provision has been made. In short, it is again confirmed that significant wealth will not be an insuperable hurdle to a successful claim.

Adult children

Adult children

My brief for this paper was to consider claims competing with variously described entitled persons by applicants within the category adult children. This has always been a contentious category, especially, at least in earlier times, that of adult sons. The position was first discussed in the New Zealand decision of Allardice v Allardice.21

In that case, the testator had been married twice, with four adult married daughters and two adult sons by his first wife, and a widow and six children from his second marriage. He left his entire estate to his second family, with no provision for the adult children. At first instance, the Supreme Court denied any provision to all of the six adult children of the testator’s first marriage; however, on appeal to the New Zealand Court of Appeal, three of the married daughters were granted provision of small amounts by monthly instalments. The court was not entirely dismissive of the claims of the adult sons, but felt that they should be self-supporting, stating:

‘As to the sons, I have doubts whether some provision ought not to be made for them. They are, however, physically able…If they had any push, they should, considering their age, have ere this done something for themselves, and to settle money on them now might destroy their energy and weaken their desire to exert themselves.’

In Australia, the adult son issue was discussed by Fullager J in In re Sinnott:22

‘No special principle is to be applied in the case of an adult son. But the approach of the Court must be different. In the case of a widow or an infant child, the Court is dealing with one who is prima facie dependent on the testator and prima facie has a claim to be maintained and supported. But the adult son is, I think, prima facie able to ‘maintain and support’ himself, and some special need or some special claim must, generally speaking, be shown to justify intervention by the Court under the Act.’

McTiernan J in Pontifical Society for the Propagation of the Faith v Scales23 stated that:

…the fact that an applicant is an adult son does not necessarily mean that relief in applications of this character must be refused. But such cases present special difficulties and, of course, before relief can be granted it must appear that the circumstances are such that the applicant is …left without ‘adequate provision for his proper maintenance and support’. But what is ‘adequate’ and what is ‘proper’ must be determined in the light of all the circumstances of the case’.24

We know that any special need requirement has been lessened. In Hughes v National Trustees, Executors and Agency Company of Australasia Ltd, Gibbs J said:

‘In some cases a special claim may be found to exist because the applicant has contributed to building up the testator’s estate or has helped him in other ways. In other cases a son who has done nothing for his parents may have a special need. This may be because he suffers from some physical or mental infirmity, but it is not necessary for an adult son to show that his earning powers have been impaired by some disability before he can establish a special need for maintenance and support. He may have suffered a financial disaster; he may be unable to obtain employment; he may have a number of dependants who rely on him for support which he cannot adequately provide from his own resources. There are no rigid rules; the question whether adequate provision has been made for the proper maintenance and support of the adult son must depend on all the circumstances…’.25

Later cases have established that there are no strict principles in awarding provision to adult sons, or to adult children generally26 but that each case is subject to judicial discretion with the circumstances of the adult child, whether of health, finances or any other relevant issue, being discussed in some detail before the judge awards whatever provision he or she thinks ‘proper’.

About twenty years ago a number of practitioners, apart from those who appeared for the executors, were surprised by an order made by Shepherdson J in Mayne v Perpetual Trustees Queensland Limited27 when the younger of two sons succeeded in an application for further provision out of the estate of their late father. It was a contest between a 56 year old son, Bill, for whom no provision was made in the will, and his 63 years old brother, John, a co-executor and the residuary beneficiary. The net value of the estate after payment of legacies to two daughters which reduced it by $300,000 was $1.36 million. Both the applicant and the respondent had been taken into a grazing partnership with their father, without paying for it, although they both worked for the benefit of that partnership and another company in which they each held a B class and C class share respectively. By the time the residuary beneficiary was in his early 50’s and the applicant in his mid 40’s, the partnership was dissolved and arrangements were made such that the applicant no longer was a member of it or a shareholder in the company. The testator formed a new partnership with the residuary beneficiary and they both continued on as shareholders in the company. Disputes arose between the two sons concerning finalisation of accounts. At the time of the hearing, the applicant’s net asset worth was said to be some $510,000. His brother’s net worth was said to be about $1.04 million.

His Honour found that Bill and John had each contributed significantly to the acquisition and build up of the testator’s assets yet the testator completely excluded Bill from his bounty. The reasons for this were set out in the will as follows:-

“I HEREBY DECLARE that I have not provided for my son WILLIAM STEWART COLBURN MAYNE because by reason of the dissolution of the family partnership of Mayne and Sons and my acquisition of his shares in the Mayne Cattle Company I am convinced that my said son has already received a full share of the family assets and therefore is not entitled to any portion of my remaining estate which is required to provide my wife my daughters and my son Walter John Colburn Mayne with an inheritance and also to reimburse my said son for practical management of my interest in pastoral pursuits and as a co executor of my estate.”

Despite argument that weight should be given to the testator’s reasons expressed in that clause in the will,28 His Honour found nothing that reflected on Bill’s character or going to conduct which could cause him to find Bill disentitled to an order in his favour. The finding that drew some interest in the appeal against His Honour’s decision was that at the date of death the applicant, Bill, was in a situation of special vulnerability in that if for any reason he was unable to continue to work his properties, his and his wife’s business would probably collapse and his son may not complete his education and that the testator must have known or should have foreseen that when he made his will success for graziers in the area was subject to the vagaries of the weather and that his grandson had not completed his education.

His Honour, in view of the size of the estate, relied on Adam J’s reference, in Re Buckland (Deceased)29:-

“The greater the estate the more may contingencies, even remote contingencies which may arise in the future, be provided for in the assessment of such maintenance”.

His Honour made provision for the applicant in the sum of $550,000 at an interest rate to that which had been provided for from the date of death by the testator in his will for the legacies for his daughters. Now, while His Honour made reference to Hughes‘ case30 which had established that there are no rigid rules applicable to an application by an able-bodied adult son and that the need to show some “special need or special claim” may generally speaking be required but it is not essential in every such case, depending on the circumstances.31

On appeal, both Fitzgerald P and de Jersey J, in a joint judgment, were critical of the reasoning of Shepherdson J’s approach to the clause explaining why the testator had excluded the applicant and his emphasis on the possibility of a recurrence of a back problem but they fell short of finding a sufficient basis for overruling the decision that adequate provision had not been made by the testator though they had difficulty in determining what matters had influenced his exercise of discretion in arriving at what they referred to as “the substantial sum of $550,000”. They said that the superior financial position and his relative lack of need did not justify an increase of what may be ordered in favour of the respondent applicant which was limited to the amount which was adequate for his proper maintenance and support. Allowing the appeal, the sum of $300,000 was substituted for the original figure.

Pincus JA also took the view there was no sufficient evidence to justify the significance attached to the circumstances concerning the contingency of the respondent’s prior back problem returning and interfering with his work capacity. He disagreed with the trial judge’s view that the respondent’s position at the date of death was one of “special vulnerability” but the finding with respect to building up the estate had justified a view that there was a moral claim which the testator should have recognised.

Even with the reduction of the value of the order for provision by the Court of Appeal, many Succession lawyers thought the floodgates had been opened, not only because of the size of the award, though reduced, but because it might otherwise have been thought that there was a serious question as to whether the applicant was entitled to any relief in light of the earlier authorities that suggested that a special need or special claim must be shown to justify intervention in favour of an adult son.32

This can be contrasted with a decision of McMeekin J in Dawson v Joyner,33 less than twelve months ago. The relevant facts can be summarized as follows. The testator died on 15 April 2009 aged 79 years. His marriage had ended in divorce in 1985-86 and a property settlement reached. The applicant, Garry, the testator’s elder son was born 25 January 1962, (49 at trial, 47 at time of his father’s death). He fell out with his father at the time of his parents’ divorce and remained estranged, at least, for the next 22 years. The respondent, Mr Leigh Joyner, the executor of the estate, opposed the application with support from the only other child of the deceased, Ross Dawson. Another beneficiary under the last will was not served as there was no intention that her entitlement would be affected in any way by any order made. Ross was born on 4 December 1963. Both sons were married although Garry, the applicant, separated from his wife Wendy in April 2010. The separation was said to be irreconcilable.

Both Garry and Ross have children — Garry’s were aged 23, 21 and 18. They were all employed. Ross has two children aged 26 and 13. The younger child, Kasey, was still a dependent student. Both Garry and Ross were in good health, as were their children, and without special needs.

The application failed. His Honour dismissed the application and said in the penultimate paragraph of his reasons for judgment:

“I can see no reason in justice why the Court should intervene here to abridge the Testator’s “freedom of testation”. In my view the applicant has failed to demonstrate that the jurisdiction of the Court is enlivened.”34

This followed a direct reference to what Young J had said in Walker v Walker35

“… Although it is not much mentioned in recent decisions, the older authorities often mention the fact that the Act did not intend to affect freedom of testation except in so far as that freedom had to be abridged in order to ensure that people made proper provision for those who were dependent on them financially or morally…”

The net value of the estate was assed at about $2.7million, the principal asset being a freehold grazing property of some 3000 acres valued at just under $ 2 million. It was part of an aggregation of three properties on which the deceased had conducted grazing operations with his brother Keith (until his death in 20030 and with Ross and his wife Marcia.

[12] The remaining assets of the estate were cash of approximately $141,000, livestock (around $156,000), shares in AMP, and a one-third interest in a grazing partnership conducted between Ross, his wife Marcia and the testator, with an estimated value of $490,000.

The testator’s will provided that, apart from a small legacy to a named beneficiary, his estate was to go to his son Ross. No provision was made for Garry.

Since he left school when he was 15, Ross lived and worked full time on the properties. Ross and his wife Marcia lived on the principal grazing property “Spotswood” for their entire married lives from March 1989 and only 200m or so from the testator. He did not remarry. Marcia did all his shopping for him and he ate with Ross’ family most nights. There was no contest that the testator became very difficult to manage in his later years. His behavior became erratic. Quite apart from the contribution made to the conservation and preservation of the family grazing properties His Honour found that Ross and his wife had made an obvious significant contribution to the testator’s welfare and happiness during his lifetime and under trying circumstances.

Until he was 23 the applicant Garry had the same relationship with the testator as did Ross. Both worked on the property as children for modest payment. Garry was sent off to Agricultural College with the intent that he return and work on the property whereas Ross stayed. As adults they were paid an award wage together with benefits such as fuel, free meat and milk, accommodation, and groceries to be charged to the testators’ account up to $30 per week.

Garry had accepted that he would work in the family business. The intention was that the aggregation would be built up by their joint efforts to enable their two families to live off the properties and that they would one day inherit them. When Garry and Wendy married they lived and worked on the property.

A property located at Dingo was bought in Garry and Wendy’s names for $164,000 in June 1984 financed partly by a loan and partly by the testator putting monies into the purchase from the family trust ($8,315), which he controlled, and a substantial sum that he had inherited from his own mother’s estate ($63,000). Ross contributed $5,000 but Gary none.

When the testator and his wife separated in April 1984. Garry thought that his father treated his mother inappropriately. The mother brought property settlement proceedings and the testator needed to raise money Garry received a letter from his father’s solicitors demanding repayment of a “loan” said to be owing in respect of the purchase of the property at Dingo.

Whether the demand was to put the testator in funds, or whether the testator perceived Garry was aligning himself with his mother in the family dispute, or whether the testator genuinely thought that an amount was owing from Garry was unresolved but within days of receiving the letter Garry had left the family property never to return. Garry claims in his evidence that when he challenged his father about the alleged loan he was threatened with violence.

Garry intervened in the family law proceedings seeking both a declaration that he did not owe any monies and an order that the testator pay him $150,000 a claim apparently based on the assertion that he had “contributed substantially to the production of income and particularly to the improvements to the properties, and to stock, plant and equipment.

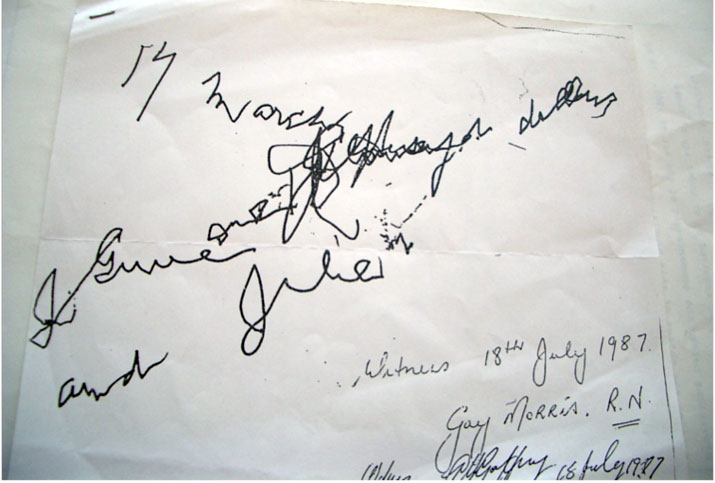

That dispute was resolved by a Deed dated 19 November 1986 between the testator, his wife and Garry. So far as Garry was concerned the Deed recorded the fact of the dispute about the existence of the loan and that the parties agreed that each “severally releases his or her rights to make an application for provision or further provision under the Testator Family Maintenance provisions of the Succession Act 1981” acknowledging that the terms agreed were to their respective advantages.

The respondent contended that whilst the clause was void in so far as it purported to preclude the applicant from pursuing his entitlements under the Succession Act 1981 it nonetheless informed the Court as to the intention behind the settlement reached — namely that Garry was severing all ties and claims on his father.

There was no communication of any sort between Garry and his family and the testator until 2007 — a period of 22 years since Garry had left the property. In 2007 the applicant commenced to visit the testator in a nursing home having been advised by Ross that their father had suffered from dementia and could no longer stay on the property but there was uncontested evidence that the testator lacked the capacity to form or maintain relationships from January 2007.

The testator had sworn a declaration in August 1992, explaining his decision to make no provision for Garry in his will prepared then, where he said that he considered that in the Family Court proceedings Garry had obtained benefits that “far exceeded” his then entitlement

and that the manner in which the proceedings had been conducted against him by his wife and Garry was “malicious, vexatious and partly fraudulent”. He had not included Garry in any of his three wills, the last being made on 20 October 2005. No meaningful reconciliation took place. While he preserved his faculties the testator displayed no wish or intention that he be reconciled with Garry, nor did Garry attempt to be reconciled with the testator.

The applicant’s financial situation

At the time of the trial, the applicant worked as a drag line operator at a mine. He earned about $150,000 p a before tax. His wife worked in the Public Service earning $1250 per fortnight. The applicant estimated his net asset position to be about $740,000 but because of the separation from Wendy, he had halved his interest in their jointly owned assets on the assumption that there would be a division of property. The respondent argued that the separation may not necessarily have been permanent pointing out that despite 20 months passing since their separation neither party had taken any step towards resolving property issues, even to the extent of consulting a lawyer. They maintained their joint interest in a partnership in a small herd of cattle, they remained amicable and Wendy retained access to a joint bank account and credit card. They also had a cane farm valued at $960,000 on the market at $1.4M.

His honour determined that the applicant’s net asset position in the sense of assets to which he had access, at the time of death, was in the order of $1.5 million and the fact that there was no evidence that, at the date of the testator’s death, the relationship was likely to come to an end was some serious relevance as the jurisdictional question was to be decided as at the date of death with the notional “wise and just testator” bringing into account all relevant facts and those that are within “the range of reasonable foresight.

Ross’ Financial Position

Ross and Marcia were comfortably off with a net asset position of about $9M. The main property worth between $6.3M and $7.3M was gifted to them by the testator during his lifetime. They also had two thirds interest in the grazing partnership valued at between about $600,000 and $1M. They also owned a news agency worth more than $1M. Their businesses were profitable.

Contribution to the Estate

Garry made no contribution to the estate at least since he left in 1985. To that time his contribution equalled his brother’s although Garry went away to College for two years and Ross didn’t. In 1985, at age 23, Garry took with him, unencumbered, the property at Dingo to which he had made no financial contribution. Ross on the other hand made a substantial contribution. He’d lived and worked on the properties all of his life as a third generation of his family to work that land.

The Jurisdictional Issue

So, to the question ‘was “inadequate provision” made for the “proper maintenance and support” of Garry? In accordance with Singer His Honour had to have regard to Garry’s financial position, the size and nature of the estate, the totality of the relationship between Garry and the deceased, and the relationship between the deceased and other persons who have legitimate claims upon his bounty.

His honour agreed with the respondent’s argument that each of those matters, save for the size of the estate, were against and not for the applicant. The size of the deceased’s estate was not insubstantial, the nature of it such that it formed part of the agricultural enterprise which the deceased conducted with Ross since Garry’s departure 26 years before. Arguably, there was no relationship between the Deceased and Garry whereas the relationship between the deceased and Ross, as his sole beneficiary, was one of years of mutual support. The deceased and Garry had clearly agreed to permanently separate their personal and commercial affairs. The deceased was clear as to why he was making no provision for Garry and Ross and Marcia had made substantial contributions to the build-up of the estate; Garry had made none.

For the applicant, two things were stressed in argument – firstly, the implications of the word “proper” in the phrase “proper maintenance and support ” and secondly, that due regard ought to be had to the concept of the testator having a duty to bear in mind the “advancement of life” of the applicant.

His Honour referred to the judgment of Callinan and Heydon JJ in Vigolo:36

“The use of the word “proper” means that attention may be given, in deciding whether adequate provision has been made, to such matters as what used to be called the “station in life” of the parties and the expectations to which that has given rise, in other words reciprocal claims and duties based upon how the parties lived and might reasonably expect to have lived in the future.”

His Honour said that his statement that Garry is not in need is not intended by me to be an attempt to reinstate the view of the law espoused by Fullager J in Re Sinnott37 and said there was no requirement in the legislation that an adult son show some special need or claim before becoming eligible to apply; but that “that is not the same as saying that the fact that an applicant is an adult son and well able to care for and provide for himself is irrelevant.

McMeekin J ordered the applicant to pay the respondent’s costs.

(Continued in Part 2)

Footnotes

- Max West, ‘The Theory of Inheritance Tax’ (1893) 8(3) Political Science Quarterly 426, 429.

- For example, see the excellent paper: Every Player Wins a Prize? Family Provision Applications and bequests to Charity, M McGregor-Lowndes and F Hannah, Australian Centre for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies, QUT, 2008

- In the period between 1290 and 1540. See generally: William F. Fratcher, ‘Protection of

the Family against Disinheritance in American Law’ (1965) 14(1) The International and

Comparative Law Quarterly 293, 294

- Ibid. The land which could be left elsewhere was two-thirds of land held by military tenure and all land held by socage. After 1660, all military tenure was converted to socage, so that all land could be left away from the heir by will.

- Forced shares for widows could be reduced by jointure or settlement, both of which

were commonly used, and by advancements for children.

- Magna Carta Ch 26: ‘If anyone holding of us a lay fief shall die, and our sheriff or bailiff shall exhibit our letters patent of summons for a debt which the deceased owed us, it shall be lawful for our sheriff or bailiff to attach and enroll the chattels of the deceased, found upon the lay fief, to the value of that debt, at the sight of law worthy men, provided always that nothing whatever be thence removed until the debt which is evident shall be fully paid to us; and the residue shall be left to the executors to fulfill the will of the deceased; and if there be nothing due from him to us, all the chattels shall go to the deceased, saving to his wife and children their reasonable shares.’

- The only remaining area where these applied after 1696 was in London.

- James Mackintosh, ‘Limitations on Free Testamentary Disposition in the British Empire’

(1930) 12(1) Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law (3rd Series) 13, 13.

- any person who was being wholly or substantially maintained or supported by a deceased (other than for full valuable consideration) at the time of the person’s death being a parent of that deceased person; or the parent of a surviving child under the age of 18 years of that deceased person; or a person under the age of 18 years: [s.40]

- (1957) 97 CLR 566 at 576

- (1994) 181 CLR 201-209

- Grey-v-Harrison [1997] 2VR 359 per Callaway JA at 366

- In Blair v Blair (2002) VSC 95 per Harper J

- (2002) VSC 202

- Re Mackinnon (2002) Tas SC 3

- Vigolo v Bostin (2001) WASC 335

- (2001) QCA 465

- Firstly, whether the disposition of the estate by the deceased was not such as to make adequate provision for the proper maintenance and support of, in this instance, the deceased’s adult son. This is a jurisdictional question which is determined at the date of death of the deceased. Secondly, if the first question is answered in the affirmative, the court in exercising its discretion to make such a provision as it thinks fit, must take into account the relevant facts existing at the time of making the order.

- Practice Direction No 8/2001, Clause 7(a).

- Vigolo v Bostin (2005) 221 CLR 191@ 204 [25]

- (1910) 29 NZLR 959, at 969-975.

- (1948) VLR 279, at 280.

- (1961-62) 107 CLR 9, at 18.

- See also on the same point: McCosker v McCosker (1957) 97 CLR 566; Stott v Cook (1960) 33 A.J.L.R. 447; Hughes v National Trustees, Executors and Agency Company of Australasia Ltd (1979) 143 CLR 134.

- (1979) 143 CLR 134 at 147.

- Bondelmonte v Blanckensee [1989] WAR 305; Hawkins v Prestage (1989) 1 WAR 37;

Wilson v Wilson (1993) unreported judgment, Supreme Court of Western Australia;

Banks v Seemann [2008] QSC 202.

- Re The Will of Mayne, BC 9202415

- In reliance upon In re Green (Deceased) (1951) NZLR 135 and especially on the passage in

the judgment of the Court of Appeal at page 141. The reference in that case was to Section 33(2) of the New Zealand legislation which finds its equivalent in the Queensland Act in Section 41(2).

- (1966) VR 404 at 415.

- Hughes v National Trustees Executors and Agency Co of Australasia Ltd (1978-9) 143 CLR 134 per Gibbs J at pages pp. 146-8.

- Supported by the view of Holland J in Kleinig v Neal (No.2) (1981) 2 NSWLR 533 at 543.

- In re Sinnott (1948) VLR 279 at 280; Hughes v National Trustees, Executors and Agency Company of Australia Limited (1979) 143 CLR 134 per Gibbs J; Anderson v Tebonera (1990) VR 527 at 539 per Ormiston J; and see judgement of Pincus JA in Mayne

- [2011] QSC 385

- Paragraph [78]

- Unreported, NSWSC, 17 May 1996 at 31

- (2005) 221 CLR 191 at [114]

- [1948] VLR 279 at280 where his Honour, Fullager J, said, “No special principle is to be applied in the case of an adult son. But the approach of the Court must be different … an adult son is, I think, prima facie able to âmaintain and supportâ himself, and some special need or some special claim must, generally speaking, be shown to justify intervention by the Court under the Act.”

The testator died in 2003 at the age of eighty three. He was survived by his defacto widow of fifteen (15) years Margaret Jones, and three (3) adult children of his first marriage — a daughter Margaret (aged 51), and two (2) sons Simon (aged 53) and Christopher (52).

The estate was worth approximately $1,474,967.38 at the time of trial — largish but not so huge by today’s standards”.39

The Will was subject to contested probate proceedings brought by Simon & Christopher alleging lack of testamentary capacity and undue influence. Those claims were abandoned after about a year.

The Will provided for Simon and Christopher Oswell to receive a legacy of $100,000 each, and for the Applicant to receive a life estate in that same amount. An education fund of approximately $800,000 for the benefit of the testator’s step grandson Lewis Jones was provided for, with this fund vesting on Lewis attaining the age of 25, or on his earlier death. Lewis also received the remainder interest in the gift of income to Margaret Oswell. The residue of the estate passed to the testator’s defacto widow, Margaret Jones.

The Applicant’s claim

The Applicant was fifty one (51) years of age at the time of the hearing.

She was severely disabled, having been born with cerebral palsy, and suffering other significant health problems. She was almost totally physically incapacitated, and was wholly dependent on others for care. She was of normal intelligence, and had no mental disabilities. It was held that she was likely to have less than the average (thirty year) life expectancy due to her condition.

The Applicant was in receipt of a Disability Support Pension and other government benefits, and had no other income or assets of any significance. She lived in state housing, which she would lose if her assets exceeded a low-moderate amount. Her modest living expenses exceeded her income.

Chesterman J found it easy to conclude that in a large estate a gift of the income on $100,000 to a child in the circumstances of the Applicant was clearly inadequate provision, and that was common ground between the parties at the hearing. The analysis then turned to the “second limb” set out in Singer v Berghouse,40 being the question of what provision should be made for the Applicant from the estate in all of the circumstances.

The competing claims of Margaret Jones and Lewis Jones were said to have significant importance, despite neither of those persons being financially needy, and Lewis Jones being outside of the class of persons for whom the testator had an obligation to provide. It was held that the testator had discharged his moral obligations to his widow (who had no real financial needs) by making the significant gifts to her favoured grandson. This indirect provision was seen as something that should be given effect to as far as possible.

The relevance of social security benefits

A question arose as to whether “the relief should be structured so that she (the Applicant) continues to enjoy the benefits of pension payments and ancillary benefits, or whether she should be given a lump sum, the whole or a substantial part of the estate, with the consequence that she will lose those benefits” .

Chesterman J considered some relevant New South Wales authorities on the issue of how pension entitlements should be taken into account, and concluded that “…the availability of…pensions and social benefits is a circumstance which should be regarded, and particularly in small estates it may be appropriate to leave an applicant wholly or partly dependent on them or to mould the provision made so that their availability is observed in whole or in part.”41

Despite the present estate being a large estate, there being a lack of competing claims having financial need, and against judicial warnings that it is for the testator to make proper provision rather than the State, Chesterman J concluded that the estate was not sufficiently large to make adequate provision for the Applicant without regard to the pension and other social security benefits being available.

His Honour then went on to fashion provision for the Applicant in a way that would retain her social security and related benefits by incorporating a Special Disability Trust into the testator’s Will.

Creation of a Special Disability Trust for the Applicant

A Special Disability Trust (“SDT”) is a form of discretionary trust settled in the usual way (with limitations), or created by the operation of a Will. It can only have one (1) beneficiary (other than on vesting), and that beneficiary must have a severe disability that meets certain criteria. The key difference between a SDT and other types of discretionary trusts is that the capital and income of a SDT can only be used to provide for the beneficiary’s “reasonable care and accommodation needs”. Care needs must arise as a direct result of the person’s disability. SDTs are therefore somewhat inflexible.

The key advantages of using a SDT are that assets of up to $500,000 (in addition to the home of the beneficiary) can be held by the SDT without those assets being included in the beneficiary’s means test for social security purposes. There are also gifting concessions for certain family members putting assets into a SDT.

A SDT was found to be desirable in the circumstances as, unlike any other form of testamentary discretionary trust or life estate, its assets would not deprive the Applicant of her social security and related entitlements.

His Honour concluded that he was unable to limit the Trust to one of income only, and so the Applicant could potentially also receive distributions of capital. It is noteworthy that this decision was left to the discretion of the Trustees appointed to the fund, who were two (2) solicitors of the firm Biggs & Biggs, the solicitors for the Applicant, rather than a trustee institution.

A fund of $500,000 was settled on the Trust, which is the maximum amount allowable for a full means test concession to be maintained.

The provision made for the Applicant

Interestingly, the provision made for the Applicant (apart from a $10,000 legacy) was limited to a gift of income, a right of residence ($450,000 for a home to be purchased and held in trust), and (in relation to the SDT only) a mere expectancy of capital distributions. The Applicant effectively received the benefit of estate assets worth $1,030,000, the capital of those assets falling back into the estate after the Applicant’s life.

As noted above, capital distributions from the SDT can only be made for housing needs (which were otherwise provided for), and needs required because of the Applicant’s disabilities. In effect, the Applicant was left to fund her “wants” from her pension.

While it was argued the applicant was entitled to a large capital sum, given that she was relatively young, suffered no mental disability, and there was capital in the estate available to give to her it became obvious and strenuously argued by the respondent there was good reason to preserve the gifts to Margaret Jones and her grandson Lewis Jones.

The provision made was seen as addressing the Applicant’s essential care, medical and accommodation needs, without going beyond “needs” to also provide for the Applicant’s “wants”.

Chesterman J commented that “the Applicant, it appears, has chosen to litigate expensively” (her costs exceeded $220,000). She was also criticised for overstating her “needs”, and implicitly the costs involved in proving those needs were not accepted as reasonable. The hearing only lasted for two (2) days.

Notwithstanding these apparent criticisms, all parties received their costs from the estate on an indemnity basis (it appears) without the need for any costs argument. No consideration was given to capping the Applicant’s costs. The costs decision could be described as generous to all parties and left the residuary beneficiary out of pocket.

The conclusion reached by the Court was that this form of indirect competing claim could legitimately be taken into account, and in some very real respects it counted against the Applicant’s claim even though the step grandson was never financially dependent on the will maker, and in fact had well-off parents and grandmother from whom he received support – perhaps a clear statement from a Court that indirect moral claims can be given significant weight.

It is interesting to note that in 1997 the New Zealand Law Commission pointed to anomalies in the Family Provision Act 1955 stating that ‘Claims by adult children under the Family Provision Act 1955 are often made on the basis not of need but on the basis that the will-maker breached an undefined moral duty and that such a regime was indefensible because will-makers cannot determine and comply with its requirements in advance, and because it may disregard moral

It is interesting to note that in 1997 the New Zealand Law Commission pointed to anomalies in the Family Provision Act 1955 stating that ‘Claims by adult children under the Family Provision Act 1955 are often made on the basis not of need but on the basis that the will-maker breached an undefined moral duty and that such a regime was indefensible because will-makers cannot determine and comply with its requirements in advance, and because it may disregard moral

imperatives of the will-maker that are not shared by whichever judge is called upon to decide the claim.42

Similarly, the Queensland Law Reform Commission, as the lead agency in the Australia-wide review of succession law, also recommended that adult children not be able to make a claim for provision, or increased provision. In clause 6 of a proposed model legislation, the eligibility for claim was to be limited to the wife or husband, a de facto partner (as defined in each jurisdiction in Australia), and non-adult children. Clause 7 additionally suggested permission of a claim by a person to whom a deceased person owed a responsibility to provide maintenance, education or advancement in life the matters that were to be taken into account,43 were listed.

But, things haven’t changed to that effect.

Step children

The usual issue in these cases is family property which has passed by joint tenancy survivorship

to the surviving step-parent. On the death of the step-parent, the question the court has

to consider is whether the step-parent gained an advantage by the survivorship which

should now be passed to the stepchild, even if an adult.

In Powell v Monteath,44 this issue was resolved by a consideration of the surrounding circumstances. The applicant stepson was in relatively necessitous circumstances and the court’s decision that he had been left without adequate maintenance and support was arrived at despite the fact that the claimant was 63 years old.