Health Commissioner Beth Wilson retires

11 December 2012

In November 2012 the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) handed down a ruling against a Mr Noel Campbell — a notorious conman who preys on the terminally ill and peddles all sorts of expensive dodgy treatments and useless gadgets.

One person who is particularly pleased by this decision is Victorian Health Services Commissioner Beth Wilson. At the end of this year, after fifteen years and three terms as commissioner, she’s retiring.

A good deal of Beth Wilson’s energies have been spent pursuing charlatans like Noel Campbell and lobbying for tougher laws to close them down.

Listen

Leveson findings urge tighter press control

4 December 2012

Lord Justice Brian Leveson has released the highly anticipated findings of his year-long inquiry into the ethics and practices of the British press. Citing the ‘outrageous’ behaviour of newspapers, Lord Justice Leveson has recommended an independent regulatory body with statutory underpinning to oversee the practices of newspapers. In an age of emerging and converging worldwide media how far does media regulation have to reach before it is effective — and how far is too far?

Listen

Family violence victims face “wall of lethal indifference”

27 November 2012

Over the last year, 60 Australian women have died at the hands of family members. As Australians commemorate White Ribbon Day around the country and pledge to take a personal stand against violence in the home, questions remain about whether we’re doing enough at a state and federal level to end the deaths, especially those of Indigenous women. Earlier this year the Western Australian Coroner released the findings into the death of Perth woman Andrea Pickett, who was murdered by her husband. The coroner found that when Andrea turned to various organisations for help — police, Indigenous legal services and domestic violence shelters — they all failed her.

Listen

For many members of the Queensland Bar, the significant role carried out by the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for the State of Queensland (ICLR) may not be at the forefront of your mind.

Over the last 12 months, the ICLR, under the direction of its Chairman, Mr John McKenna SC, has conducted a major review of its operations. This review has resulted in the development of important changes to the services that the ICLR provides. These changes are designed to improve the quality, efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the services provided by the ICLR to the courts, the legal profession and the public in Queensland.

The purpose of this article is to provide members of the Bar with details of these important developments, which will be implemented from1 January 2013. The ICLR looks forward to the support of members of the Bar, for the exciting new initiatives that are outlined below.

What is the ICLR?

The ICLR is a charitable corporation, which was established in 1907.

The principal object of the ICLR is:

“the preparation and publication in a convenient form, at a moderate price, and under gratuitous professional superintendence and control, of Reports of Judicial Decisions of the Supreme Court in the State of Queensland.”

To the extent that it is able to do so, the ICLR also has as a subsidiary object:

“to supplement or assist any of the libraries of the Supreme Court of the State of Queensland by gifts…of such profits of the Association as the Council shall from time to time determine to donate.”

The ICLR is under the control of a 9 member Council, which comprises three practising barristers and three practising solicitors, who are appointed annually by the Judges of the Supreme Court, together with the Attorney-General, the Solicitor-General and the Registrar of the Supreme Court, to the extent they wish to exercise their ex officio entitlement to sit on the Council. At present the Council comprises Mr John McKenna SC (Chairman), Mr Declan Kelly SC, Ms Helen Bowskill, Mr Chris Coyne, Mr David O’Brien, Ms Rachael Miller and Ms Julie Steel.

The principal function of the ICLR is to publish the authorised reports of the Supreme Court of Queensland – the Queensland Reports.

As a subsidiary function, the ICLR also prepares and publishes a weekly print publication, the Queensland Law Reporter. This publication contains advance summaries of forthcoming reports of cases, recent practice directions of the court, and legal notices published for those who wish to advertise a proposed application to the court (in particular, applications for admission to the legal profession and applications for probate or administration).

The long-standing problem of identifying key decisions

One of the key issues confronting the ICLR is how to provide a solution to the problems that presently arise because of the sheer volume of unreported Supreme Court decisions.

The vast majority of these decisions, whilst of great significance to the parties concerned, involve no change or clarification to the general law. They usually involve nothing more than an orthodox application of established principle to a particular factual dispute. The sheer volume of these decisions, however, is beginning to overload Australian legal information databases, making it harder to identify the key decisions which truly redefine or clarify the law.

The problem of identifying, from the morass of new judgments, those decisions which truly develop or redefine the law is not simply a product of the digital age.

Even at the time of Queensland’s foundation, in 1859, vast numbers of English decisions – many of very little significance – were reported in a wide variety of reports, journals and newspapers. This was the era of the Law Journal Reports, the Solicitors Journal Reports and many separate sets of nominate reports. This approach was followed in the new Colony of Queensland, with virtually every new decision of the Supreme Court being extensively reported in local newspapers or journals, including the Queensland Law Journal.

In 1901, however, the Chief Justice of Queensland (Sir Samuel Griffith) believed it was time that the key decisions of the Supreme Court of Queensland were extracted and preserved in a set of official reports, to be modelled upon the new approach to authorised law reporting which had been developed in England.

This involved establishing a Council of Law Reporting — an independent body under the control of the legal profession and the Supreme Court — which would be responsible for making a suitable selection of cases and then publishing authorised reports of these decisions at a moderate cost.

The unique feature of these authorised reports was that they were the product of a four stage process of:

- selection — to make sure that only cases which materially redefined or clarified the law were chosen for reporting;

- checking — to make sure that each report was free from any textual error, and that all quotes and references were correct;

- summarising — to include a headnote which quickly and accurately identified the key facts and points of importance; and

- authorisation — to allow the deciding Judge a final opportunity to revise and approve the report before publication.

From 1902, these authorised reports began to be published as the State Reports of Queensland – with notes of practice decisions being published as the Queensland Weekly Notes.

From 1908, these reports were supplemented by another weekly publication, the Queensland Law Reporter. This supplement provided the profession with advance notice of new cases which were thought to be of sufficient importance to justify inclusion in the Queensland Reports, and carried a range of public notices (including probate and admission notices) which were required by the Rules of Court or Practice Directions.

Once this system was established, it became the practice to cite only authorised reports of Queensland judgments in submissions to the courts.

Challenge of unreported judgments

Whilst this system of law reporting proved to be effective in Queensland for almost 100 years, new challenges have arisen because of the large number of unreported judgments which are now published on court websites every week.

For courts and practitioners alike, the sheer volume of this material is creating a serious and deep-seated problem. It affects those who seek to read new judgments to keep up-to-date with the law, as well as those searching for answers to specific legal problems, who now find themselves confronted with scores of marginally relevant cases. It also affects the courts, who are now being burdened with numerous citations of unreported judgments which add nothing of substance to established principle.

Selecting key cases

In the Council’s view, there is only one practical solution to this problem — an early application of expert and perceptive judgment to select, from the morass of new cases, those which truly develop or clarify the general law.

The Council was delighted that its Senior Editor, Mr RM Derrington SC, was prepared to take on this role. Mr Derrington SC is one of Queensland’s leading commercial silks, having been in practice for some 22 years. In reviewing new cases, he is able to draw upon advice from a panel of practitioners with specialties which cover the full range of the Court’s jurisdictions.

As well as reviewing all new cases for reporting, Mr Derrington SC also monitors earlier decisions which are cited in more recent cases, to ensure that no key decisions are mistakenly excluded from the reporting process.

The fundamental importance of skilled selection, in the context of scholarly law reporting, to the development of the common law was recently emphasised in the first annual BAILII lecture presented by Lord Neuberger, the new President of the UK Supreme Court, on 20 November 2012 ( http://www.supremecourt.gov.uk/docs/speech-121120.pdf , particularly at [35]-[40] ).

New Queensland Reports website

The practical implementation of this process will involve the introduction of a rapid case classification and monitoring system, which will be available on a free new website ( www.queenslandreports.com.au ).

The system is quite simple.

Every week, all new decisions handed down by the Supreme Court of Queensland will be reviewed and analysed by Mr Roger Derrington SC, with a view to rapidly isolating the key decisions of the Court which truly redefine or clarify the law.

These key decisions will then be briefly summarised and indexed — using the conventional Queensland Reports classification system – and added to a Key Judgments database on the Queensland Reports website. These cases will also be notified to the profession and the judiciary every week through a free email service – the relaunched Queensland Law Reporter. Appeals from these key decisions will then be monitored, with updates also provided through the Queensland Law Reporter.

As a general rule, all the cases on the Key Judgments database — unless reversed or overtaken by an appeal decision — will then proceed to be fully reported and headnoted, in authorised form, in the Queensland Reports. The aim is to ensure that the Queensland Reports continues to be a reliable source of all key decisions of the Supreme Court.

Special treatment, however, will be given to key decisions dealing with matters of practice or procedure. These cases, which often do not justify inclusion in the Queensland Reports, will be collected together in a new Key Practice Decisions database on the website.

In the initial phase of the website, it will also include, in addition to the Key Judgments database and the Key Practice Decisions database:

- a free printable backset of recent Queensland Law Reporters;

- a free searchable database of probate and administration notices; and

- background information about the history and role of authorised law reports in Australia.

These innovations are only some of the changes which are planned to be introduced to the Queensland Reports, over the next two years, to meet the needs of the modern legal system.

New Queensland Law Reporter

The launch of the new Queensland Reports website will coincide with the launch of a new Queensland Law Reporter.

The new Queensland Law Reporter will be available for email delivery, free of charge, from January 2013.

The new Queensland Law Reporter has been designed to allow the Editors of the Queensland Reports to communicate directly to the whole of the judiciary and legal profession every week — and so provide key information, which is not readily available elsewhere, about the latest developments in the law of Queensland.

The new Queensland Law Reporter will contain a weekly update of:

- all new legislation, rules of court and practice directions which affect practice in Queensland State courts;

- all new cases which have been added to the Key Judgments database, and the progress of appeals in these cases; and

- all new headnotes of cases being published in the Queensland Reports.

The Queensland Law Reporter will also include the familiar public notices concerning applications for probate and admission — but now reformatted in a way which will ensure that they are easier for busy practitioners to scan.

Changes in the Queensland Reports

The speed and quality of the Queensland Reports has also been the subject of careful review.

To ensure that the quality of the headnotes in the Queensland Reports reaches the highest academic standards, the Council has appointed a former Professor of Law at the University of Queensland — Dr Sarah Derrington — to the position of co-editor. In this role, Dr Derrington is responsible for settling all headnotes which are prepared for publication in the Queensland Reports by a team of specialist sub-editors and reporters.

This new editorial team has dramatically reduced the time lag between the delivery of judgments and the date of their publication in the Queensland Reports. They are now close to achieving their object of publishing authorised reports of judgments within six months of their delivery.

With these developments, the ICLR hopes to further enhance the contribution of the Queensland Reports to what Lord Neuberger describes as “judgment enhancement” ( www.supremecourt.gov.uk/docs/speech-121120.pdf at [33], [41]-[42]).

How can you access the new QLR?

The new website – www.queenslandreports.com.au – will be operational from 1 January 2013.

The ICLR encourages all members of the Bar to register at www.queenslandreports.com.au , from 1 January 2013, in order to obtain the free email Queensland Law Reporter, and take advantage of the useful legal information databases which appear on the website.

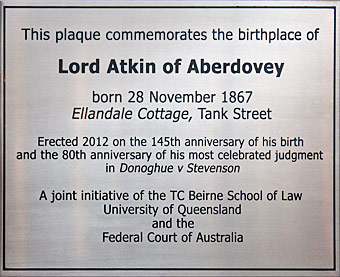

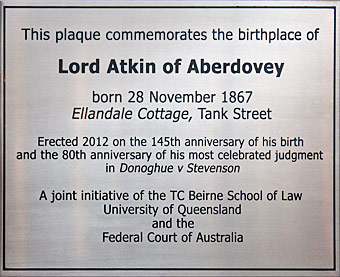

The University of Queensland and the Federal Court of Australia co-hosted an event to commemorate the birthplace of Lord Atkin of Aberdovey, one of the world’s most influential common law judges, at a ceremony in Brisbane on Wednesday 28 November 2012.

Lord Atkin was born on 28 November 1867 in Tank Street, Brisbane.

1867 in Tank Street, Brisbane.

Chief Justice of the Federal Court Patrick Keane and Lord Atkin’s grandchildren Sir Thomas Atkin Morison and Elizabeth Barry unveiled a commemorative plaque dedicated to Lord Atkin in the Tank Street Courtyard at Brisbane’s Commonwealth Law Courts.

The placing of the Lord Atkin plaque was an initiative of UQ’s Dean of Law, Professor Gerard Carney, and the Federal Court of Australia.

Sir Thomas, a retired UK High Court Judge, and Mr and Mrs Barry travelled from the UK to attend the ceremony.

They also visited several local landmarks significant to their great-grandparents’ early days in Queensland after emigrating from the UK during the mid to late 1800’s.

The Hon. Chief Justice Patrick Keane, Mrs Elizabeth Barry (granddaughter of Lord Atkin), The Hon. Sir Thomas Morison (grandson of Lord Atkin).

The family said the trip was a wonderful opportunity to discover more about their family’s connection to Queensland.

“I’ve learned more about my family as a result of what Gerard Carney has managed to find out than I ever knew before, so we’re immensely grateful,” Sir Thomas said.

“It’s quite emotional; it isn’t just the memory of my grandfather but of his remarkable parents who were pioneers who came out here after months at sea during which time they lost one family member and were very nearly shipwrecked.”

“Then coming to have 200 square miles of territory in Queensland, it’s a remarkable thing to do, so we have enormous admiration for his parents.”

Mrs Barry said she was particularly delighted to see the display of photographs, books and memorabilia put together by the Federal Court Library to highlight the key events and achievements of Lord Atkin’s life.

Professor Carney said Brisbane should be proud of its connection with one of the most famous judges of the common law world.

“Although he left Australia as a young child, his compassionate judicial philosophy was no doubt influenced by the liberal contribution his parents made to the political life of Brisbane during the early years of the colony,” Professor Carney said.

“Both parents were journalists and his father, Robert, was a prominent member of the Queensland Parliament.”

“I am very grateful to the judges of the Federal Court for supporting this initiative.”

Lord Atkin moved from Brisbane to the UK with his Welsh mother and siblings in 1870 at the age of three, after the early death of his prominent father, Robert Atkin.

After studying at Magdalen College Oxford and reading for the Bar at Gray’s Inn, Lord Atkin served as a judge from 1913 until his death in 1944.

He was elevated to the House of Lords in 1928 where he delivered his two most famous judgments in Donoghue v Stevenson in 1932, and Liversidge v Anderson in 1942.

Donoghue v Stevenson, commonly referred to as the “snail in the bottle” case, was a radical step forward in the law of negligence and experts believe that Lord Atkin’s judgment contains the most influential statement of legal principle used in the common law world to this day.

The case changed the course of the common law by setting the foundation for the tort of negligence, brought about when one party fails to exercise a reasonable standard of care to prevent harm to another, such as in personal injury claims, product liability and consumer law.

Lord Atkin married Lizzie Hemmant, the eldest daughter of prominent Brisbane businessman and politician, William Hemmant.

Professor Gerard Carney, (Dean of Law, TC Beirne School of Law), The Hon. Chief Justice Patrick Keane, Mrs Elizabeth Barry (granddaughter of Lord Atkin), The Hon. Sir Thomas Morison (grandson of Lord Atkin).

Professor Gerard Carney, (Dean of Law, TC Beirne School of Law), The Hon. Chief Justice Patrick Keane, Mrs Elizabeth Barry (granddaughter of Lord Atkin), The Hon. Sir Thomas Morison (grandson of Lord Atkin).

Background

Conduct and Compensation Agreements (CCAs) are a modern day feature of resource legislation. The legislature seeks to encourage relevant resource authority holders and landholders to voluntarily enter into agreements about access, the conduct of authorised activities on land and compensation liability rather than compulsorily impose such matters upon the landholder. Compulsory powers and traditional compensation dispute resolution processes are positively discouraged in the absence of parties using all reasonable endeavours to voluntarily enter into a CCA.

The usual legislative formula is to provide:

(a) that the resource authority holder is not to access or enter private land to carry out authorised activities unless an appropriate CCA has been entered into;

(b) for the relevant resource authority holder to be liable to compensate each owner or occupier of private land in the area of the authority for any compensatable effects the eligible claimant suffers that is caused by relevant authorised activities; and

(c) that parties to use all reasonable endeavours to negotiate an appropriate CCA.

In Queensland, similar if not equivalent provisions relating to CCAs exist in each of the main pieces of resource legislation, including the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (“MRA”), Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (PAG Act), Petroleum Act 1923, Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009 and the Geothermal Energy Act 2010. The purpose of this paper is to examine a number of aspects relating to CCAs including:

(a) legislative requirements for CCAs under those Acts;

(b) issues faced by parties, particularly landholders, in negotiating CCAs; and

(c) the general measure of “compensation liability”.

Legislative Requirements

Sections 10 and 13 of Schedule 1 of the MRA, the provisions dealing with CCAs for exploration permits and mineral development licences, for example, provide as follows:

“10 Conduct and compensation agreement requirement for particular advanced activities

(1) A person must not enter private land in an exploration tenement’s area to carry out an advanced activity for the tenement (the relevant activity) unless each eligible claimant for the land is a party to an appropriate conduct and compensation agreement. Maximum penaltyâ500 penalty units.

(2) The requirement under subsection (1) is the conduct and compensation agreement requirement.

(3) In this sectionâ

appropriate conduct and compensation agreement , for an eligible claimant, means a conduct and compensation agreement about the holder’s compensation liability to the eligible claimant of at least to the extent the liability relates to the relevant activity and its effects.”

and

“13 General liability to compensate eligible claimants

(1) The holder of each exploration tenement is liable to compensate each owner or occupier of private land or public land in the tenement’s area (an eligible claimant) for any relevant authorised activities.

(2) An exploration tenement holder’s liability under subsection (1) to an eligible claimant is the holder’s compensation liability to the claimant.

(3) This section is subject to section 11.

(4) In this sectionâ

compensatable effect means all or any of the followingâ

(a) all or any of the following relating to the eligible claimant’s landâ

(i) deprivation of possession of its surface;

(ii) diminution of its value;

(iii) diminution of the use made or that may be made of the land or any improvement on it; (iv) severance of any part of the land from other parts of the land or from other land that the eligible claimant owns;

(v) any cost, damage or loss arising from the carrying out of activities under the exploration tenement on the land;

(b) accounting, legal or valuation costs the claimant necessarily and reasonably incurs to negotiate or prepare a conduct and compensation agreement, other than the costs of a person facilitating an ADR;

Examples of negotiation â

an ADR or conference

(c) consequential damages the eligible claimant incurs because of a matter mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b).

relevant authorised activities means authorised activities for the exploration tenement carried out by the holder or a person authorised by the holder.”

Virtually identical access and general compensation liability provisions for advanced activities are contained in ss 500, 532 of the PAG Act; ss78Q, 79Q Petroleum Act 1923; ss283, 320 of the Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009 and ss216, 247 of the Geothermal Energy Act 2010.

Under each Act, the legislation provides that an eligible and a relevant authority holder may enter a CCA about how and when the authority holder may enter the land and how authorised activities under the relevant authority to the extent that they relate to the eligible claimant must be carried out and the holder’s compensation liability to the claimant or any future compensation liability that the holder may have to the claimant under the relevant authority (see s 14 Sch 1 MRA; s 533 PAG Act; s79R Petroleum Act 1923; s321 Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009; s248 Geothermal Energy Act 2010).

The requisite requirements or contents of a CCA are that:

(a) a CCA cannot be inconsistent with the Act, a condition of the relevant authority or a mandatory provision of the land access code and is unenforceable to the extent of that inconsistency;

(b) a CCA must provide for the matters mentioned in the earlier provisions, in particular:

(i) how and when the authority holder may enter the land;

(ii) how authorised activities must be carried out;

(iii) the holder’s compensation liability for any future liability to the claimant;

(c) must be in writing and signed by or on behalf both the authority holder and the eligible claimant;

(d) state whether the CCA is for all or part of the liability;

(e) if it is for only part of the liability state the details of each activity or affect of the activity to which the agreement relates and the period for which the agreement has effect; and

(f) provide for how and when the compensation liability will be met.

(see ss 14, 15 Sch 1 MRA; ss 533, 534 PAG Act; ss79R, 79S Petroleum Act 1923; ss322, 323 Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009; ss248, 249 Geothermal Energy Act 2010)

A CCA may relate to all or part of the liability or future liability (s 14 Sch 1 MRA; s 14(3) MRA; Sch 1 MRA; s 533(3) PAG Act; s79R(3) Petroleum Act 1923; s321(3) Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009; s248(3) Geothermal Energy Act 2010).

In addition, a CCA may provide for other matters including:

(a) monetary or non-monetary compensation. For example, a CCA may provide for the construction of works such a road or a fence;

(b) a process by which it may be amended or enforced. For example, it may provide for compensation to be reviewed on the happening of a material change in circumstances;

(c) may provide for compensation that is or may be payable under the Environmental Protection Act 1994.

(see s 14 Sch 1 MRA; s 533(2) PAG Act; s79S(2) Petroleum Act 1923; s322(2) Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009; s249(2) Geothermal Energy Act 2010)

Negotiation Process Issues

Each Act imposes a positive obligation upon both the resource authority holder and landholder to use all reasonable endeavours to negotiate a CCA.

Starting the Negotiation Process

Strangely, the negotiation process can only be initiated by the relevant authority holder and not by the landholder. No doubt the expectation of the legislature is that, as a authority holder cannot access or enter private land to carry out advanced relevant activities unless it has complied with the negotiation process, the incentive rests only upon the authority holder to commence the negotiation process. Until an authority holder enters upon the land, there is no need for a landholder to commence the negotiation process.

However, it is conceivable that in two instances a landholder may wish to instigate negotiations: the first is in the case of preliminary activities or activities other than advanced activities for which access can be gained by a resource authority holder without first negotiating a CCA; the second is in the case of compensatable effects suffered by the landholder caused by authorised activities on neighbouring lands in the same tenement or tenure. In each those cases, a landholder may wish to instigate the negotiation process in order to obtain proper compensation. How would the landholder do so? It is probably only with the aid of the additional jurisdiction of the Court.

Duty to Provide Information

Clearly, in order for a landholder to be able to fairly and properly participate in the negotiation process, the landholder needs to be properly informed and provided with full details of the relevant authorised activities proposed to be carried out on his land and from which he may suffer compensatable effects.

Some resource authority holders have been lax in recognising the clear implicit obligation which exists to provide landholders with full details of proposed relevant activities. It is insufficient for such details to be described generally. As a matter of natural justice and statutory obligation, a landholder is entitled to insist upon the provision of adequate or sufficient information or disclosure in relation to the activities proposed to be carried out in order to complete the negotiation process. Indeed, until provision of such sufficient information or disclosure was provided, the authority holder can be considered to have failed to use all reasonable endeavours to negotiate a CCA and, therefore, lawfully complete the negotiation process.

It is likely that an authority holder would be restrained from proceeding further with the process limiting its ability to enter upon land unless and until it provided the landholder with full and proper information concerning the relevant activities for which the legislature intends there be a CCA. Alternatively, pre-trial disclosure is likely to be ordered. Under all normal modern day Court rules, disclosure of all directly relevant documents in the possession or power of the resource authority holder is a usual requirement.

Most resource companies do recognise the need for landholders to be properly and fully informed of the relevant activity, not only as a matter of natural justice and ensuring the use of all reasonable endeavours to negotiate but also in terms of the requirements of the Act that the CCA detail each activity or the effect of the activity to which the agreement relates. Some, however, are yet to recognise the necessity of this basic obligation to provide full and proper information to landholders.

Prescription of Activities

It is important and in the interest of both parties that each activity and the effects of each activity be clearly prescribed in a CCA. It is important for a number of reasons:

(a) to ensure the resource authority holder has clear authority to enter the land and undertake the relevant activities;

(b) to ensure that questions of whether a material change in circumstances has occurred, such as to entitle a landholder to a review of compensation, can be easily determined;

(c) to ensure that the landholder receives full compensation;

(d) to ensure that the extent of the discharge of the resource authority holder’s compensation liability can be clearly and accurately identified in a CCA.

Finality and Completion of Negotiation Process

The clear intent from the relevant provisions is that, once the negotiation process commences, the process proceed through the negotiation period with both parties using all reasonable endeavours to negotiate a CCA or Deferral Agreement. Provisions use language such as “On the giving of the negotiation notice, the … holder and the eligible claimant (the parties) must use all reasonable endeavours to negotiate a CCA or Deferral Agreement” (see eg s 17 Sch 1 MRA; s 536 PAG Act; s79U Petroleum Act 1923; s324 Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009; s251 Geothermal Energy Act 2010).

At the end of the minimum negotiation period the legislature, each party has the election to ask the relevant officer to call a conference or to call upon the other party to agree to an alternative dispute resolution to continue the negotiation. Upon such an election notice being given, the parties again “must use all reasonable endeavours” to finish the negotiations (see s 23 Sch 1 MRA; s 537AB PAG Act; s79VAB Petroleum Act 1923; s325AB Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009; s255 Geothermal Energy Act 2010). Following the expiration of such a conference or ADR, an eligible claimant or the holder may then apply to the Land Court for review of the compensation.

The parties having embarked upon the negotiation process, and landholders, particularly, having expended time and costs doing so, the legislature intends that the process proceed to determination either by agreement in a CCA or referral to the Court for review.

It does not intend that either the resource holder or the landholder unilaterally ‘opt out’ of the statutory process intended for the entering into a CCA or determination of compensation upon that process having been embarked upon. This seems to have been an erroneous view taken by some parties.

ADR Attendance and Costs

Two issues, primarily for landholders, concerns, first, the inability to enforce attendance of a party to an ADR as the other party has to agree to it and if a conference is called, the other party has to agree with authorised officer’s decision to approve attendance of legal representatives.

Secondly, it is remarkable and quite unfair that, if a landholder calls upon a resource authority holder to agree to an alternative dispute resolution process, that the landholder must bear the costs of the person who will facilitate the ADR and not have those costs recoverable, even in the event of a successful negotiation. Such costs plainly would not be incurred but for the compulsory process imposed upon the landholder and the failure of the negotiation process to that point.

There seems no rational reason for an ADR process not to be compulsory if elected nor for the costs of the person facilitating ADR not to form part of the landholder’s disturbance costs.

Misleading and Deceptive or Unconscionable Conduct

Clearly, obligations under the Competition and Consumer Act and Fair Trading Act relating to misleading and deceptive conduct and/or unconscionable conduct apply to CCA negotiations.

It behoves resource authorities to ensure that land access agents and others who represent them in negotiations, particularly those conducted directly with landholders, be vigilant to ensure that their representations or promises as to the nature and extent of activities that will occur on land, the extent to which activities may or may not affect the land are not misleading or deceptive and that they conduct themselves conscionably. There is clear risk that, in the hurry to sign up landholders, matters may be misrepresented or understated or dealings unconscionably occur. The courts will protect weak and disadvantaged persons, particularly persons who have been misled or whose bargaining power is unconscionably taken advantage.

It is only a matter of time before a CCA is set aside on this basis.

Legal Representation

Whilst legal representation is not a strict necessity, resource authority holders ought to be aware of the whole body of law developed in the 1980’s surrounding the then practice of banks having persons, who were not legally represented or had not received independent legal advice, execute security documents. The absence of independent legal advice was an important factor taken into account by Courts in determining whether the bargaining power of persons was unconscionably taken advantage of. It has resulted in the almost universal practice now adopted of acknowledging the opportunity of independent legal advice being signed by mortgagors.

It ultimately benefits both resource authority holders and landholders that CCAs are properly entered into and properly drafted with the input, where appropriate, of independent legal representatives so as to ensure not only fair dealings but that the bounds of relevant activities and extent of compensation liability discharged are clearly prescribed, understood and agreed upon. Resource authority holders, as much as landholders, do not want fights later about such matters.

Two Tier Negotiations

An area of serious concern relates to the two tier negotiation tactics adopted by some resource authority holders. By “two tier”, I mean the adoption of a strategy whereby resource authority holders conduct negotiations in respect of the same matters on two fronts: formally through legal advisers but, at the same time (often in direct contradiction to the request of the landholder through his or her legal advisor), by direct approach or contact by land assess agents and/or other person with landholders.

These tactics are clearly unconscionable and, most likely, unlawful, particularly if a request has been made for all dealings to occur only through the landholder’s legal advisor. As a practice, it should desist. The clear purpose is to seek to avoid the landholder having the benefit of independent legal advice and/or to influence or coerce the landholder into an agreement.

Measure of Compensation

The compensation liability of each resource authority holder is to compensate each owner or occupier of private land for any “compensatable effect” the eligible claimant suffers caused by the relevant authorised activities.

“Compensatable effects” are defined (see s13 Sch 1 MRA; s532(4) PAG Act; s79Q Petroleum Act 1923; s320(4) Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2009; s247(4) Geothermal Energy Act 2010) as follows:

“compensatable effect means all or any of the followingâ

(a) all or any of the following relating to the eligible claimant’s landâ

(i) deprivation of possession of its surface;

(ii) diminution of its value;

(iii) diminution of the use made or that may be made of

the land or any improvement on it;

(iv) severance of any part of the land from other parts of the land or from other land that the eligible claimant owns;

(v) any cost, damage or loss arising from the carrying out of activities under [the relevant authority] on the land;

(b) accounting, legal or valuation costs the claimant necessarily and reasonably incurs to negotiate or prepare a conduct and compensation agreement, other than the costs of a person facilitating an ADR;

Examples of negotiation â

an ADR or conference

(c) consequential damages the eligible claimant incurs because of a matter mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b).”

Matters of General Principle

The clear purpose of the above provisions is to provide compensation. And compensation is the critical concept with regard to understanding those provisions.

The concept of compensation in the above legislation has not been given a character which is different from that which applies in other area areas of law. “It is to place in the hands of the owner expropriated the full money equivalent of the thing of which he has been deprived. Compensation, prima facie, means recompense for loss and when an owner is to receive compensation for being deprived of real or personal property his pecuniary loss must be ascertained by determining the value to him of the property taken from him” (see Nelungaloo Pty Ltd v The Commonwealth (1948) 75 CLR 495 at 571; applied in Wills v Minerva (supra) at 316).

The provisions are concerned with the loss occasioned to the landholder and the individual aspects of those provisions need to be considered within that paradigm.

The provisions closely align with other compensation provisions upon which there have been Land Court or Resource Tribunal decisions. Whilst the duty of the Court, when construing legislation, is to give effect to the purpose of that individual piece of legislation by giving the words of that legislation their natural and ordinary meaning, assistance may be derived from matters of valuation principle determined under other legislation, including the Acquisition of Land Act 1967 (ALA). As Mr Scott stated in Michael J Wills v. Minerva Coal Pty Ltd (1998) 19 QLCR 297 as regards s 281 of the MRA:

“In matters of compensation arising under s 281 MRA, it is to that provision that a Court must first turn, however, as is the practice of Courts in all jurisdictions: in searching for principle or the conceptual treatment of an issue, assistance may be sought from other relevant areas of law including in the present case that involving the question of compensation flowing from the compulsory acquisition of land to the extent that there is no inconsistency with s 281 MRA. There are broad similarities between the compulsory acquisition of an interest in land and the imposition of a mining lease over land. It follows that even without detailed analysis of s 281 MRA one could anticipate benefit from consideration of the law of compensation for compulsory acquisition. There is a natural and understandable similarity.”

This is particularly apt in those projects declared an Infrastructure Facility of Significance under the State Development and Public Works Organisation Act 1971. In those cases, the powers of compulsory acquisition by the Coordinator General may ultimately be called in aid, in which case, compensation will be assessed under the provisions of the ALA.

With the above in mind, turning to the specific words within the definition of “compensatable effects”, the following general principles may usefully be distilled as applying :

(a) The definition neither prescribes nor suggests a method of assessment or valuation. The selection of an appropriate method will be a matter for the relevant expert. It is also well established, as Callinan J observed in Boland v Yates Property Corporation Pty Ltd (1999) 74 ALJR 209 at 267, that there is no legal principle that purports to, or could close for all times, the categories or methods of valuation which might be acceptable in a particular case. A method can only be “closed” if the Act, properly construed, led to that result.

(b) The “value” of the land and improvements with which the definition is concerned is the value to the owner ascertained in accordance with the authority of Spencer v. The Commonwealth (1907) 5 CLR 418 especially at 441. In Stubberfield v The Valuer-General [1991] 1 Qd R 278, Carter J described market value as follows at 283:

“In Spencer v The Commonwealth [1907] 5 C.L.R. 418 the High Court propounded the proper test for the assessment of land value. It is the price which a willing purchaser would at the date in question have had to pay to a vendor not unwilling, but not anxious to sell. It seems to me that that test finds statutory expression in the Valuation of Land Act. In defining “unimproved value” for the purposes of the Act, it recites that that value is the capital sum which the fee simple of the land might be expected to realise if offered for sale on such reasonable terms and conditions as a bona fide seller would require. In simple terms it is synonymous with the market value of the land.”

(c) The land is to be treated according to its highest and best use. This requires the valuer to determine the diminution in value of land on the basis of a price that would be paid for it assuming the most advantageous purpose for which the land is adapted and which is legally possible and economically feasible. Where land to be valued enjoys in whole or in part a characteristic or advantage, even if not reflected in its present use, the Court must find the notional market price which includes full allowance for that potentiality (See eg Turner v Minister for Public Instruction (1956) 95 CLR 245; Raja’s case [1939] AC 302 at 313; McKenna v Burnie Municipality (1970) 22 LGRA 402 at 409; Yates Property Group Pty Ltd v Darling harbor Authority (1971) 73 LGRA 47. However, obviously it is essential that a mere potential not be treated as a reality.

(d) The measure of compensation should place the landholder in the same financial position as he enjoyed before the activities.

(e) The value of land is the value to the landholder which is deemed to be the amount which the landholder himself would pay for the land rather than use it;

(f) “Diminution of its value” should be understood to refer to the diminution in value of the whole of the land as a consequence of the relevant activities. To confine the diminution to the area of relevant authorised activities would mean that (iii) would be similarly confined – a result not intended by the legislature (Wills v Minerva (supra) at 319).

(g) The acquiring authority itself may be considered a purchaser of acquired land which may add to its value.

(h) Where part only of a landholder’s land is acquired the landholder is entitled not only to the value of the land taken but also to compensation for all consequential losses including severance and injurious affection.

(i) The language in the phrase “diminution of the value”, invites the use of the “before and after” method of valuation if practicable, or at least a method of valuation which recognises that compensation to be assessed is the measure of the difference between the value of the landholder’s land before the activities and the value after the activities.

(j) Injurious affection is the type of damage done to the retained land which flows from the exercise of any statutory powers by the resource authority holder injuriously affecting the retained land. This type of damage is related to the uses of, or activities on the land and the consequent depreciation in value of the retained land (see, for example, Suntown Pty Ltd v Gold Coast City Council (1979) 6 QLCR 196; Marshall v Department of Transport (Qld) (201) 205 CLR 603).

(k) “Diminution of the use made or that may be made of the land or any improvement on it” comprises what is usually called “injurious affection” arising from the impact of activities. It refers to the diminution in use either present or potential of the land or any improvements and thus repeats part of the language in item subparagraph (ii). The provision is not directed towards the area activities, but to the balance land and improvements (Wills v Minerva (supra) at 319).

(l) Such language is quite different to that considered in Sullivan v Oil Co of Aust Ltd & Anor [2003] QCA 570 where the Court of Appeal held that the then language in the Petroleum Act 1923 did not evince an explicit or implicit intention to include injurious affection. Whilst some resource authority holders cling valiantly to that decision, the language of the current legislative provisions, including the PAG Act and amendments made to the Petroleum Act 1923, now permits for a much broader construction. The MRA provisions have long been held to allow for injurious affection; including since Sullivan (see eg Watts v QCoal Pty Ltd & Ors [2007] QLRT 23). An express purpose in the Explanatory Notes for the new PAG Act, when it was introduced, was to bring gas in line with MRA provisions.

(m) Following upon the decision in Marshall, it is not only the activities or constructions on the acquired land for which injurious affection is claimable but any injurious affection resulting from the exercise of the constructing authority’s activities in pursuance of the relevant scheme.

(n) Damage for the purposes of injurious affection is not confined to physical damage to the remaining land but any other injurious consequence resulting from the activities which depreciates the value of or increases the cost of using the other land. If the exercise of the power limits the activities on or the use of the land, interferes with the amenity or character of the land, deters purchasers from buying the land, the claimant is entitled to compensation (see Marshall supra at 625-626).

(o) The dispossessed owner, in appropriate circumstances, is entitled to an additional payment on the ground that he has been disturbed. As identified by Mr Scott in Wills v Minerva Coal Pty Ltd (supra) there are two general types of disturbance. The first of these is connected with the use of the land by the owner and the leading authority on this is The Commonwealth v. Milledge (1953) 90 CLR 157, the application of which has been consistent throughout Australian jurisdictions. The second type of disturbance relates to such expenses as legal, valuation and any other expert fees associated with the preparation of a claim for compensation. Such expenses are payable up to the date of lodgement of the claim in the Court.

(p) An owner cannot receive an amount for compensation for disturbance which is inconsistent with the basis adopted for the assessment of the value of land acquired. In other words, if the loss of any value of the land is made on the basis of a potential future use for which the present use must be abandoned, disturbance expenses cannot be based on the basis of the present lesser use.

(q) Any increase or decrease in the value of the land due entirely to the scheme for which compensation is payable is to be disregarded (referred to as the Pointe Gourde principle after the seminal decision in Pointe Gourde Quarrying and Transport Co Ltd v Sub-Intendent of Crown Lands [1947] AC 565).

(r) It is the duty of any dispossessed owner to take all reasonable measures to mitigate his loss.

The application and relevance of the above principles (and the methods used by a valuer in forming his assessment of compensation) will depend upon the nature of the case in particular circumstances and apply to a greater or lesser degree to various instances. However, they are a useful touchstone in any assessment.

Application in Practice

Generally speaking, the measure of compensation recoverable is dependent upon a number of factors, the most significant of which are: whether the land or any improvements taken from the owner are taken permanently or such that the owner is unable to use the land; or, if the owner retains the right to use the land, to what extent is that right interfered with.

Often the resource authority holder’s rights taken over an area are only temporary or partial and occur by way of an easement. In such cases, the value of any right to use the land will be dependent upon the infrastructure constructed and the terms and conditions of the easement agreement. The normal approach is:

(a) to allow 100% diminution in value of the land and improvements where infrastructure or surface rights are granted within an easement area (eg a compressor station or an access track along a pipeline);

(b) to allow a percentage diminution in the value of land improvements within an easement area where rights are only temporary or partial by nature or duration (eg buried pipelines or temporary work areas).

In addition to any percentage diminution in value of the land, a disturbance allowance also may be made for production losses during the construction period and rehabilitation period. In the case of grazing properties, this is usually measured on the basis of the carrying capacity of the land multiplied by the growth in kilograms per day and the dollar value of live weight per kilogram over the construction period. So, for example, in the case of a construction area directly impacting upon 3 hectares of land with a carrying capacity of 1AE per hectare the equation would be: 3AE x 1kg per day x $2.20 per kg x 180 days construction period.

A buffer area (in addition to that construction area directly impacted upon by works) also may be allowed, depending upon the effects of activities to areas external to the construction area. For example, in the case of works comprising high levels of noise or activity, particularly of an irregular nature, a buffer area of up to 500 metres may be supported by the evidence. Of course, the impacts of such activities within such buffer area will be of a graduating nature – from 100% closest to the works to 0% impact at the far edge. An average 50% may therefore be adopted so as to take account of this graduation. Accordingly, in a buffer area of, say, 10 hectares, again with 1AE per hectare, the equation may be thus: 10AE x 1kg x $2.20 per kg x 180 days construction period x 50%.

Following the construction phase there also may be period of rehabilitation whereby pasture grasses will need to rehabilitate. In certain instances, the most appropriate means for allowing this rehabilitation to occur may be to destock or not use the relevant lands. In other cases, graduating production losses over the period of rehabilitation may be calculated, for example, graduating from the time when production is totally lost to a time when full production is regained. In the case of grazing lands, it is not unusual for such rehabilitation periods to be up to three years with production losses calculated on the basis of 100% for the first year, around 60% for the second and 20% for the third year.

As regards injurious affection, in the case of grazing lands, the following matters, inter alia, may give rise to injurious affection:

(a) the loss of ability to operate the property as a vertically integrated breeding, growing and fattening property;

(b) the loss of flexibility to a operation;

(c) reduction in breeding capacity;

(d) loss of all weather or improved access;

(e) loss of water reticulation resources;

(f) a need to re-establish stock water;

(g) loss of cattle yard;

(h) need to refigure fencing;

(i) impacts caused by noise, particularly from blasting, loading trucks, vehicle movements, unloading trucks, etc;

(j) a reduction in pasture grown;

(k) increased management time or expenses;

(l) over capitalisation of the property having regard to the loss of grazing areas.

Each case will depend on its own circumstances. Any injurious affection to the value of the balance lands caused by impacts of the above kind is recoverable. Usually this again is measured by percentage diminution in value of the balance lands.

An aspect often of some controversy is owner’s management time. The suggestion sometimes made by some resource companies that management time is not payable is ignorant. Owner’s management time has been long recognised as compensable either as disturbance or, alternatively, as a consequence of severance. The more legitimate issue relates to the quantum of the extra management time required and its value.

Date of Assessment/Valuation

The date of assessment of compensation liability for resource authority activities is different to that which occurs under the ALA in which case there is a specific date of resumption. In the case of a resource authority compensation liability, the assessment or determination of compensation is as at the date of negotiating the CCA or at trial but recognising that the activities may not occur for some time into the future.

In those cases, where there is a postponement of payment until after the issue of a construction notice or activities commence, there is an obvious need alos to recognise and ensure present day calculations of compensation are appropriately indexed for the delay in payment.

Liberal Estimate Principle

The High Court has on several occasions emphasised that in compensation cases a principle that requires doubts to be resolved in favour of a more liberal estimate in favour of a claimant. In Commissioner of Succession Duties (SA) v Executor Trustee and Agency Co of South Australia Ltd (1947) 74 CLR 358 Dixon J stated at 373-374:

“[T]here is some difference of purpose in valuing property for revenue cases and in compensation cases. In the second the purpose is to ensure that the person to be compensated is given a full money equivalent of his loss, while in the first it is to ascertain what money value is plainly contained in the asset so as to afford a property measure of liability to tax. While this difference cannot change the test of value, it is not without effect upon a court’s attitude in the application of the test. In a case of compensation doubts are resolved in favour of a more liberal estimate, in a revenue case, of a more conservative estimate.”

The above statement of Dixon J was later affirmed by the High Court in Gregory v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1971) 123 CLR 547 at 565 and more recently in Boland v Yates Property Corporation Pty Ltd (1999) 74 ALJR 209 at 279-280. In Marshall v Director General Department of Transport (2001) 205 CLR 603 McHugh J simply stated (at 627) that “Such legislation should be construed with the presumption the legislature intended the claimant to be liberally compensated …”

In McBarnon v Traffic Authority New South Wales (1995) 87 LGERA 238 Talbot J stated at 244-5:

“… it is appropriate to seek to do justice by adopting a generous approach in favour of the resumee to ensure that just compensation is paid so far as the Act allows. Therefore, any discretion should be exercised in favour of the claimant where practicable in order to achieve a just result.”

Conclusion

There may be benefits in removing the determination of compensation liability from formal modes of adjudication such as those adopted by the Courts. However, in the absence of formalised procedures as to due process and fairness, the disadvantage is that landholders may potentially be mistreated in their dealings.

It is the responsibility of all who are involved to ensure that CCA negotiations occur fairly and through well informed and fair processes so as to provide legitimacy to outcomes. In the absence of that occurring, inevitably, one way or another, determinations of compensation liability will not be finalised and further issues will arise with the real risk of litigation occurring in any event.

EJ Morzone

Changes from the 1995 Workplace Health And Safety Act (“The Repealed Act”)

Duties

Under the Act, what is called the “primary duty of care” falls upon persons who conduct businesses or undertakings (PCBU). It is owed to their workers and other workers when at work in the business or undertaking. A less onerous duty is owed to others at the workplace (s.19). There are also duties cast on PCBUs conducting specific types of undertakings, for example designing plant, substances, or structures for use in workplaces; they have more specific duties for activities which may impinge on a workplace (s.20 — 26). Finally there are duties which are cast on those who work within the business/undertaking, namely officers of the PCBU, workers in the business or undertaking or others at the workplace (s.27 — 29).

Officers of PCBUs

“Officer” is more broadly defined than “executive officer” under the repealed legislation.

Under the repealed legislation, the executive officer was required to ensure a corporation complied with the repealed Act, and under the Act an officer of a PCBU must exercise due diligence (which is defined) to ensure that the PCBU complies with its obligations. In both cases, a failure to exercise reasonable diligence/due diligence to ensure compliance makes the officer liable for the breach. The major differences are:

1. That the onus now lies on the prosecution to prove an absence of due diligence, rather than on the defendant to prove reasonable diligence was exercised; and

2. That arguably, under the repealed Act, it was necessary to convict a corporation first, whereas the liability of an officer arises independently of the conviction of the PCBU, under the Act.

It is in the area of offences and their prosecution that particularly significant changes have been brought about by the Act.

The liability structure

Under the repealed Act there was a single offence of failing to perform an obligation. The level of penalty depended on whether there were health consequences of the breach, and varied according to the level of the consequence. Under the Act there are significant changes to:

(a) The offences;

(b) The way they are to be prosecuted or defended;

(c) The appellate structure.

The New Offences

There are three categories of offence, with different elements and different outcomes, dependent, not on consequence of conduct, but upon the seriousness of the conduct itself. There are other offences concerned with the administration of the Act — e.g. s.188 — 190 with respect to hindering, obstructing, impersonating, assaulting etc. of inspectors exercising their powers, but I don’t intend to refer further to these latter types of offences.

The maximum penalties are significantly greater, and the level of liability will vary according to the status of the offender.

The most serious offence is the Category 1 offence (s.31) which is designated as a crime, and pursuant to s.3 of the Criminal Code is an indictable offence and must be prosecuted on indictment, (that is before a judge and jury, or in rare cases, a judge alone).

Category 2 and Category 3 offences (s.32 and 33) are simple offences and must be prosecuted summarily under the Justices Act (s.230).

A common element for each category is that the person charged owes a health and safety duty.

For a Category 1 offence, the prosecution must also prove:-

(a) That the PCBU, without reasonable excuse, engaged in conduct that exposed an individual, to whom the duty is owed, to the risk of death or serious injury or illness;

and

(b) The PCBU was reckless as to the risk to an individual of death or serious injury or illness.

For a Category 2 offence, the prosecution must, additional to the health and safety duty, prove that the PCBU has failed to comply with the duty and further that the failure exposed an individual to a risk of death or serious injury or illness.

For a Category 3 offence, the prosecution must establish, in addition to the health and safety duty that the PCBU failed to comply with the duty.

In each case, the level of penalty in ascending order of seriousness is dependent upon whether the perpetrator is:

(a) An individual;

(b) An individual, either as a PCBU or as an officer of a PCBU; and

(c) A corporation.

For Category 1 offences, levels (a) and (b) each includes a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment. Corporate maximum penalties run up to $3,000,000.00. The duty imposed on a PCBU requires that the PCBU eliminate or minimise risks to health and safety insofar as is reasonably practicable.

For a Category 1 offence, the prosecution must also prove an absence of “reasonable excuse” for the impugned conduct, i.e. the liability is not absolute.

Sections 23 (unwilled act/accident) and 24 (mistake of fact) of the Criminal Code apply to Category 1 offences, but have limited, if any, application to Category 2 and Category 3 offences (s.33A).

Strict Liability

Of the above offence creating provisions, s.31 is clearly not one involving strict liability. Firstly, liability is limited by the words “without reasonable excuse” and by the requirement of recklessness. Further, liability is potentially limited by the possible application of ss.23 and 24 of the Criminal Code (see s.33A of the Act).

On the other hand, once a duty is established, the Category 2 and Category 3 offences seem to me to be fairly clearly strict liability provisions.

This also highlights the major structural change in the offences as compared to the repealed Act.

Under that Act there was an underlying offence, which was aggravated if identified consequences occurred.

The Category 1, 2 and 3 offences are not concerned with consequences, but with exposure to risk. Each is a discrete offence. The penalty levels are not dependent on circumstances of aggravation, but on the category of offence and the classification of the offender.

Health And Safety Duties

Section 19 of the Act identifies the primary duty of care which is to ensure the health and safety of workers engaged by, or whose activities are influenced, by a PCBU, and the health and safety of others whose health and safety may be affected by the conduct of the business or undertaking insofar as is reasonably practicable.

Other duty creating provisions (ss. 20 — 26) relate to PCBUs conducting specific undertakings and are also defined in terms of “reasonable practicability”.

Section 27, which establishes the duty of officers of PCBUs, requires the exercise of due diligence, and s.28 and 29, which deal with the duties of workers and other persons at workplaces are drafted in terms of requiring reasonable care to be exercised by those persons.

This tends to ameliorate the hardship of the strict liability created by ss.32 and 33 by establishing duties in terms of reasonable practicability or reasonable care, but once the duty is established, strict liability applies to a breach of the duty.

On the face of the Act this creates a harsh penalty regime, especially for Category 2 offences.

To summarise, duties are cast in terms of:

(a) Ensuring, so far is reasonably practicable, health and safety (for PCBUs);

(b) Exercising due diligence to ensure PCBUs comply with their duty (for officers of PCBUs);

(c) Taking reasonable care and complying so far as they are reasonably able (for workers, and others, at workplaces).

The phrases I have underlined have been analysed by courts in some circumstances, and in some cases will develop further, with judicially identified meanings.

The phrase “so far as is reasonably practicable” was considered by the High Court in Baiada Poultry Pty Ltd v. R (2012) HCA 14. At paragraph 15 of their judgment, the plurality said of this phrase:

“All elements of the statutory description of the duty were important. The words “so far as is reasonable practicable” direct attention to the extent of the duty. The words “reasonably practicable” indicate the duty does not require the employer to take every possible step that could be taken. The steps that are to be taken in performance of the duty are those that are reasonably practicable for the employer to take to achieve the identified end of providing and maintaining a safe working environment. Bare demonstration that a step could have been taken and that, if taken, it might have had some effect on the safety of a working environment does not, without more, demonstrate that an employer has broken the duty imposed by s.21(1). The question remains whether the employer has so far as is reasonably practicable provided and maintained a safe working environment.”

At paragraph 33 the plurality said this:

“The question presented by the statutory duty “so far as is reasonably practicable” to provide and maintain a safe working environment could not be determined by reference only to Baiada having a legal right to issue instructions to its subcontractors. Showing that Baiada had the legal right to issue instructions showed only that it was possible for Baiada to take that step. It did not show that this was a step that was reasonably practicable to achieve the relevant result of providing and maintaining a safe working environment. That question required consideration not only of what steps Baiada could have taken to secure compliance but also, and critically, whether Baiada’s obligation “so far as is reasonably practicable” to provide and maintain a safe working environment obliged it: (a) to give safety instructions to its (apparently skilled and experienced) subcontractors; (b) to check whether its instructions were followed; (c) to take some step to require compliance with its instructions; or (d) to do some combination of these things or even something altogether different. These were questions which the jury would have had to decide in light of all of the evidence that had been given at trial about how the work of catching, caging, loading and transporting the chickens was done.”

As to the requirement to exercise “due diligence” imposed upon officers, in ASIC v Healey and ors. 278 ALR 618 at para 165, Middleton J (in the Federal Court) said at page 180, dealing with entirely different legislation:

“In determining whether a director has exercised reasonable care and diligence, as s.180(1) expressly contemplates, the circumstances of the particular corporation concerned are relevant to the content of the duty. These circumstances include: the type of company, the provisions of its constitution, the size and nature of the company’s business … and the circumstances of the specific case.”

Whilst the issues to be looked at in the context of a Workplace Health and Safety prosecution will be different from the specific issues to be considered in Healey, it indicates the way a Court is likely to regard this issue. At paragraph 180 his Honour said:

“Section 180 requires that a director exercise due care and diligence. Making a mistake does not demonstrate that due care and diligence was wanting. The standard required of professionals, and directors, is a reasonable care and skill and does not require perfection.”

Finally, it should be said that the issues are of course questions of fact with the answers to whether or not the conduct fits the requirements varied according to the circumstances of the particular case.

Appeals

Section 668D of the Criminal Code permits an appeal to the Court of Appeal against a conviction or sentence for an indictable offence (Category 1 offences). Otherwise, an appeal lies to a judge of the District Court, and then on matters of law to the Court of Appeal, for Category 2 and Category 3 offences. This is a significant change from the previous appellate structure, which permitted an appeal as of right only to the Industrial Court, and then Judicial review if jurisdictional error could be established (Kirk v. IRCNSW)1.

This short analysis of the offence-creating and appellate provisions shows that there have been substantial changes to the way such matters are to be litigated, many of which are to my mind positive.

Firstly, and most importantly, the legislature has done away with an offence structure which permitted the prosecution to simply prove an obligation, prove an incident (most prosecutions follow death or injury) and then in effect challenge the defendant to prove one of the narrow defences available pursuant to s.37 of the repealed Act, of operating within the regulatory framework, or that the commission of the offence was due to causes over which the defendant had no control. Proof of either, especially the first, was particularly difficult.

Now it will be necessary for the prosecution to prove the elements of the offence including, for a Category 1 offence, that the defendant engaged in the impugned conduct without reasonable excuse, and prove that ss. 23 and 24 of the Criminal Code, if raised on the evidence, have no application, if raised on the evidence.

The new provisions, it will be seen, are more focused on punishment of conduct, rather than consequence, although I expect that prosecutions will nonetheless continue to follow largely upon serious incidents.

The new structure brings about what, to my mind, is the desirable outcome of bringing these offences into the mainstream of the criminal justice system, and away from the industrial system. Appeals will be either direct to the Court of Appeal (Category 1 offences) or to a judge of the District Court (Category 2 and Category 3 offences). This gets away from the difficulties of the “specialist tribunal” referred to in both judgments of the High Court in Kirk2 .

Particularisation

It is to be hoped that this will lead to a more open approach by the prosecution to their task — in particular to provide proper particularisation of offences, which will in turn lead to fewer pre-trial applications which currently need to be brought in almost every case. Most of us thought that the proper particularisation of charges would always be required by courts after the decision in Kirk.

Since the decision of the High Court in Kirk3 and more recently of that Court in Patel4, the need to request and to obtain particulars in criminal trials has been highlighted for practitioners. In my view, the effect of the decision in Kirk has been narrowed down by decisions of the Industrial Court and the Supreme Court in the matter of Collins5,6 and 7.

However, we may see some significant change in the light of:

(a) The change in the jurisdiction in which these matters are litigated; and

(b) The effect of the decision of the High Court in Patel which has again emphasised the importance of both seeking and being given detailed particulars of any charge.

Investigative Powers

The heavy penalties contemplated by the Act are supported by strong powers granted to investigators. In addition to the usual powers to issue improvement notices and prohibition notices, the regulator and inspectors have wide powers to investigate suspected breaches of the Act:

(a) Powers of entry (without a warrant) to premises that are, or are reasonably suspected of being, a workplace. These powers are set out at ss.163 to 166;

(b) Pursuant to search warrant, an inspector may enter premises for the purposes of obtaining evidence within a specified time — see ss.167, 168 and 169;

(c) Significant powers are granted upon entry (see ss.171 to 181). It includes a power in certain circumstances to require the provision of name and residential address (see s.185).

What should be noted about these powers in particular is that pursuant to s.172 privilege against self-incrimination is abrogated. However, there are severe limitations placed upon the admissibility of evidence obtained pursuant to s.172. Pursuant however to s.269, legal professional privilege is specifically retained.

A particularly important section in this regard, at least for the first couple of years of the Act’s operation, is s.282. This is a transitional provision for investigative powers and is far from clear in its application. From my brief experience of the Act, it would appear that different inspectors have different interpretations of how the Act applies to their exercise of power.

My view of the provision is that s.282 means that the investigative powers which may be utilised in conducting investigations into offences said to have occurred under the repealed legislation are limited to the powers that existed under that legislation. The somewhat greater powers, (for example, s.172,) in my view do not apply to investigations of offences said to have occurred under the repealed legislation. However, I am unaware of any decision made by any Court on this issue. I certainly accept that a contrary view may prevail.

These investigative powers are further supported by obligations on PCBUs to immediately notify the Regulator of a notifiable incident (see ss. 35 — 39).

The person with management or control of a workplace, at which a notifiable incident has occurred, must ensure non disturbance of the site until an inspector arrives or directs otherwise.

Own Investigation

A most difficult issue confronting those with responsibility for workplaces is whether to conduct an investigation of a notifiable incident. In addition to the expense of such an investigation, the person runs the risk that the incident investigation report will be used against them. On the other hand, one hesitates to suggest that people shouldn’t carry out investigations as this will often help to prevent any further occurrence of notifiable incidents and may be necessary in some circumstances to fulfil one’s duties under the Act. It is of course relevant on prosecution, and in particular on punishment,  that a PCBU has made enquiries and made changes to overcome a set of circumstances that created an exposure to risk. The best approach is, if a report is to be obtained to do so for the purpose of seeking advice from a lawyer as to rights and prospects and to have the report commissioned by the lawyer. In this way it’s likely to be protected by legal professional privilege.

that a PCBU has made enquiries and made changes to overcome a set of circumstances that created an exposure to risk. The best approach is, if a report is to be obtained to do so for the purpose of seeking advice from a lawyer as to rights and prospects and to have the report commissioned by the lawyer. In this way it’s likely to be protected by legal professional privilege.

Defending allegations of failure to ensure workplace health and safety usually relies upon the evidence of relevant experts, properly briefed as to the circumstances of the notifiable incident. Always remember however, that whatever is given to an expert in commissioning a report, will of necessity, be required to be given to the prosecution if you wish to rely upon the report and if the report puts any reliance on the material.

Identifying and defending “failures”

1. The first thing to ask is whether the prosecution is under the current Act or under the repealed legislation.

2. It is necessary to identify whether the offence charged is to be heard on indictment or summarily.

3. The next matter is to consider an approach to obtain the particulars upon which the prosecution rely in bringing the allegation. However, there will be times when such an approach is not wise.

4. When you have particulars you will then need to look at the evidence, both for the prosecution side, and from the point of view of the defence, that is available to support or negative the issues raised by the particulars. It is here that a significantly different approach is possible to defending prosecutions under the Act as against prosecutions under the repealed legislation. It is now possible to properly defend the allegations without calling evidence. Under the repealed legislation it was almost impossible to do so — I can’t think of a single case where that was a serious consideration. Circumstances may require the calling of evidence in prosecutions under the Act, but it will not be as often as was previously the case. It is a matter that needs to be considered very carefully because it affects the order of addresses which, particularly in jury cases, is an important matter.

Joinder of Charges

It is interesting to note that the old joinder provisions have been substantially changed. Section 164(2) of the repealed Act provided:

(2) More than 1 contravention of a workplace health and safety obligation under part 3 may be charged as a single charge if the acts or omissions giving rise to the claimed contravention happened within the same period and at the same workplace.

Section 233(1) of the Act provides:

“1. Two or more contraventions of a health and safety duty provision by a person that arise out of the same factual circumstances may be charged as a single offence or as separate offences.

2. This section does not authorise contraventions of two or more safety duty provisions to be charged as a single offence.”