Australia is attractive as a venue for international commercial arbitration. It is a Model Law country and has been a party to the New York Convention for many years.

International commercial arbitration is a consensual dispute resolution process for transnational commercial disputes.1 As an important aspect of international commerce, it has in recent decades proven spectacularly successful and has been recognised for some time as the preferred method for resolving such disputes.2 Its proliferation has led to the development of an “internationally recognised harmonised procedural jurisprudence”, which combines the best practices of both the civil and common law systems, taking into account diffuse cultural and legal backgrounds and philosophies. The new jurisprudence is establishing a generally accepted procedure for dispute resolution which is of benefit to international arbitration, as well as modern jurisprudence generally.3

Arbitration (international and domestic) is readily distinguishable from other forms of dispute resolution and has been described as “litigation in the private sector”.4 It is seen to offer many advantages over litigation including neutrality, confidentiality, expedition, party autonomy, flexibility in procedure, relative informality, the ability to choose the “judge”, and transnational enforceability of awards. These perceived advantages are integral to its success.

The commonwealth and state parliaments have recently legislated to improve the laws that govern commercial arbitration, both internationally and domestically which has served to enhance Australia as an arbitration friendly venue.5 Superior courts have established specialist arbitration lists to facilitate the resolution of disputes by arbitration. The Australian International Disputes Centre (AIDC) has been set up as Australia’s leading dispute resolution venue.6 The recent High Court decision in the TCL case, confirming in emphatic terms the constitutional validity and juridical basis of the International Arbitration Act 1974 (Cth),7 has significantly assisted in this process.

Arbitration agreement — the foundation of the arbitral process

The foundation of the arbitral process is the agreement by which the parties refer their disputes to arbitration. Once a binding arbitration agreement is entered into, the parties will be subject to it, so that if a dispute arises which falls within its scope, such dispute must be resolved by arbitration (if a party requires it). Unless settled by agreement, the arbitral process will culminate in an award capable of enforcement with curial assistance. The arbitration agreement’s terms will bind the parties, as well as the arbitrator appointed pursuant to it.8

An essential quality of the arbitration agreement is that it is considered to be a contract independent of the contract in which it is contained. On this basis, the arbitral tribunal can rule on its own jurisdiction even if the underlying contract has been terminated or is set aside.9

An arbitration agreement will commonly deal with such matters as the types of disputes which fall within its terms, the seat of the arbitration (which will determine the lex arbitri), the law according to which the dispute will be determined (the lex causa), a set of procedural rules, the number of arbitrators and their appointment, and the language of the arbitration. Parties may decide to incorporate the rules of a recognised arbitration institution and adopt the institution as the appointing authority, or to proceed ad hoc.

In Australia it is possible to use both international and local arbitral institutions. The major arbitration institutions, such as the ICC, LCIA; regionally, the SIAC, HKIAC, KLRCA, and CIETAC; and in Australia, the ACICA and ACDC; have recommended arbitration clauses, or the parties can devise their own.10

Scope of agreement

An issue that often arises concerns the scope of an arbitration clause — whether a particular dispute falls within its terms. If it does (in the face of opposition), the matter (or part) cannot be litigated in the courts. This issue will often arise when a court is asked to stay a court proceeding on the ground that the issues fall within the terms of an arbitration agreement.11

Arbitrability

A similar issue is the question of arbitrability which involves determining which types of dispute may be resolved by arbitration and which must go to court. This determination will be made initially by the arbitral tribunal, but may ultimately be made by courts of particular states applying national laws. Despite the principle of party autonomy, there are disputes which by their very nature must be determined by the courts, for example, insolvency, criminal proceedings, divorce, or registration of land or patents.12

International arbitration dependent on local laws

For international commercial arbitration to operate and be effective, the process must be supported by at least two bodies of national, or local, laws: first, the lex arbitri, which will give legal force and effect to the process of the arbitration; and second, national laws which enact or legislate for the enforcement mechanisms of the New York Convention (NYC).13

The NYC is the single most important factor explaining the success of international commercial arbitration. So far 148 countries have acceded to it. It is primarily concerned with two matters:

⢠the recognition of, and giving effect to, arbitration agreements; and

⢠the recognition, and enforcement, of international (non-domestic) arbitral awards.

It achieves the first by requiring a court of a contracting state to refer a dispute which has come before it, and which falls within the scope of an arbitration agreement, to arbitration; and the second by enabling the successful party to an arbitration award to easily and simply enforce the award in any country which is a party to the NYC in accordance with that country’s arbitration laws.14

Model Law — a template arbitration law

The next most influential international legal instrument in the present context is the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law Model Law (UNCITRAL) on International Commercial Arbitration, commonly known as the Model Law. The Model Law is not legally effective on its own, but is simply a template for legislation for an arbitration law (a lex arbitri) which may be enacted by individual states.15

In Australia, the lex arbitri is the International Arbitration Act 1974 (Cth) (IAA). Its stated objects are, inter alia, to give effect to Australia’s obligations under the NYC, as well as to give effect to the Model Law and the ICSID Convention. The IAA gives the Model Law force of law in Australia and cannot be excluded by the parties. The two principal matters addressed by the NYC are dealt with by the IAA.16

The jurisdiction to set aside an arbitral award is pursuant to Art 34(2) of the Model Law. Jurisdiction for enforcement, recognition and setting aside of awards is exercisable by the Federal Court, or if the place of arbitration is in a state or territory, the Supreme Court thereof.17

Procedure and evidence — how determined

If the parties to an international commercial contract have inserted an arbitration clause into their contract, which incorporates a set of arbitration rules, then these rules will govern issues of procedure and evidence, subject to the particular lex arbitri having mandatory provisions which govern procedural issues and which cannot be overridden by the parties or the arbitrator. Subject to this, the parties and the arbitrator will be able to adapt the chosen rules to suit the particular circumstances of a dispute.

Interim relief

Arbitration rules, such as the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, and applicable national laws (lex arbitri), such as those based on the Model Law, give the arbitral tribunal and sometimes local courts power to make interim orders in aid of the final award (which relief may be enforced in local courts).18

What remedies are available

While in general terms in international arbitrations arbitrators can give the sorts of remedies and relief that national courts can, what an arbitral tribunal can give in a particular arbitration will depend on the arbitration agreement, including any arbitration rules the parties have agreed to, the lex causa and the lex arbitri. Awards that may be made include payment of a sum of money, declarations, specific performance, injunction, rectification, costs and interest.19

Awards, setting aside, enforcement and challenges

The making of a binding and enforceable award by the arbitral tribunal is the object and purpose — indeed, the culmination — of the arbitration process. For both the arbitrator and the parties (or at least the successful party), it is critical that this be achieved. For the award to be enforceable it must, inter alia, be reasoned, deal with all the issues — but only those issues — referred to arbitration, effectively determine the issues in dispute, be unambiguous, be intelligible, correctly identify the parties and comply with all essential formalities.20 The particular lex arbitri engaged will set requirements which an award must contain. The precise requirements for an award will principally be determined by the arbitration agreement (incorporating any arbitration rules) as modified by the lex arbitri.21

If the arbitral process is subject to some irregularity in procedure (and in a limited range of other circumstances), the award is liable to be set aside, or refused recognition or enforcement. As noted, the circumstances by which an award may be set aside are set out in Art 34 of the Model Law, and those on the basis of which it may be refused enforcement or recognition are contained in Art 36. The circumstances under Arts 34 and 36 are virtually identical.

The domestic situation — the uniform Model Law Commercial Arbitration Acts

The Standing Committee of Attorneys-General (SCAG) meeting on 7 May 2010 agreed to implement the model Commercial Arbitration Bill 2010 based on the Model Law as uniform domestic arbitration legislation. The previous legislative regime of uniform Acts in force in Australian states and territories had several marked differences to the Model Law. New South Wales was the first state or territory to enact the Commercial Arbitration Act 2010. The Victorian legislation, the Commercial Arbitration Act 2011, came into operation on 17 November 2011. Most other states and territories have now followed suit.22

Conclusion

International commercial arbitration has proven spectacularly successful in the post-war era and will no doubt continue to be so. Australia offers many attractions as a venue and seat for international commercial arbitration, including an adherence to the rule of law, an expert legal profession, a stable political system and courts that have “an excellent record for enforcing foreign arbitral awards”.23 Both internationally and domestically it is a Model Law country and has been a party to the NYC for many years. With the greater opportunities for trade and commerce on the international stage brought about by globalisation, and notably the rise of Asia, Australia is well positioned to be an important hub for international commercial arbitration.24

By John K Arthur

John K Arthur is a member of the Victorian Bar practising in commercial litigation, wills, estates and other civil matters with a particular interest in dispute resolution.

1. This article is an abridged and revised version of a paper by the author delivered at the Law Institute of Victoria, Essentials Skills, CPD program, 14 March 2013, entitled “An Introduction to International Commercial Arbitration” available at www.gordonandjackson.com.au/online-library (posted 25.03.13)(“Arthur”). See The International Arbitration Act 1974: A Commentary, M. Holmes, and C. Brown, Lexis Nexis, 2011; and generally, Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration, Student Edition, by Redfern, Hunter, Blackaby and Partasides, 5th Ed., Oxford Uni. Press, 2009; International Arbitration: A Handbook, by Phillip Capper, 3rd Ed., LLP, 2004; Court Forms Precedents and Pleadings — Victoria, Arbitration by D. Byrne, updated by D. Bailey, Lexis Nexis; Doug Jones, International Commercial Arbitration and Australia, 2-3 March 2007, available atwww.claytonutz.com/area_of_law/international_arbitration /docs/International_commercial_arbitration_and_Australia.PDF (“Doug Jones”)

2. TCL Air Conditioner (Zhongshan) Co Ltd v The Judges of the Federal Court of Australia and Anor [2013] HCA 5 at [10](“TCL case”); The Hon. P. A. Keane, Justice of the High Court, (2013) 79 Arbitration 195-207; 2013 International Arbitration Survey, PWC and Queen Mary, University of London, School of International Arbitration. Available at: www.arbitrationonline.org/docs/pwc-international-arbitration-study2013.pdf and past years’ surveys.

3. Rt Hon. Sir Michael Kerr, Concord and Conflict in International Arbitration (1997) 13 Arbitration International 122 at 125-6.

4. Sir John Donaldson in Northern Regional Health Authority v Derek Crouch Construction Co Ltd & Anor [1984] 2 All E.R. 175 at 189 cited in Doug Jones at p2.

5. International Arbitration Amendment Act 2010 (Cth) and the new Commercial Arbitration Acts in the states which substantially enact the Model Law domestically; see R. Kovacs,“Putting Australia on the arbitration map” (2012) 86 LIJ 36.

6. For example, Arbitration List G of the Supreme Court of Victoria, and see “Arbitration law reform and the Arbitration List G of the Supreme Court of Victoria” by Hon Justice Croft, available on Supreme Court of Victoria website; in NSW, Commercial Arbitration List and see Practice Note No. SC Eq 9; in the Federal Court, see Practice Note ARB 1 — Proceedings under the International Arbitration Act 1974, and see “The Federal Court of Australia’s International Arbitration List” by Hon. Justice Rares available on Federal Court website; The AIDC, established in 2010 with the assistance of the federal and NSW governments, houses leading ADR providers including the Australian Centre for International Commercial Arbitration, the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (Australia) Limited, the Australian Maritime and Transport Arbitration Commission and the Australian Commercial Disputes Centre. Seewww.disputescentre.com.au.

7. TCL case, see note 2 at [11], [12], [17], [29], [45], [81], [101].

8. See note 14; Rizhao Steel Holding Group Co Ltd (2012) 287 ALR 315; 262 FLR 1; [2012] WASCA 50 at [165]—[166].

9. See note 14; Rizhao Steel.

10. International Chamber of Commerce, London Court of International Arbitration, Singapore International Arbitration Centre, Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre, Kuala Lumpur Regional Centre for Arbitration, China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission, Australian Centre for International Commercial Arbitration, Australian Commercial Disputes Centre. Arbitration clauses which are inexpertly drawn may be flawed and inefficacious — so called “pathological” clauses.

11. Under s7(2)(b) IAA.

12. Redfern and Hunter at [2.111]; [2.114].

13. Capper at p11ff. Five systems of law may apply to international commercial arbitration: Redfern & Hunter, at p165, cited in Cape Lambert Resources Ltd v MCC Australia Sanjin Mining Pty Ltd [2013] WASCA 66 [36].

14. The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards made in New York on 10 June 1958 known as the New York Convention; Redfern & Hunter at p72; the 148 countries which have acceded to the NYC are the vast majority of countries in the world. On 16 April 2013 Myanmar also acceded to the NYC: www.newyorkconvention.org/new-york-convention-countries/contracting-states; Articles II and IV NYC.

15. The 1985 Model Law was revised in 2006, available at www.uncitral.org.

16. First, the enforcement of foreign arbitration agreements; and secondly, the recognition, and enforcement, of foreign awards by ss8 and 9 IAA.

17. Section 18IAA. For applications to enforce a foreign award, or set aside an award, see Civil Procedure Victoria, Lexis Nexis, at [II 9.04.05]ff. See also Altain Khuder LLC v IMC Mining Inc (2011) 246 FLR 47; [2011] VSC 1; reversed on appeal in IMC Aviation Solutions Pty Ltd v Altain Khuder LLC (2011) 253 FLR 9; [2011] VSCA 248.

18. For example, freezing orders: Art 17(2)(c). Under the IAA local courts provide assistance to the arbitration process in a variety of ways, including a request to refer a matter to arbitration (s8). As to enforcement of interim measures in courts, see Art 17H.

19. Capper at pp113-117; as to interest see ss25 and 26 IAA.

20. Redfern & Hunter at p553ff; ibid, Capper at p118. Eg. Art 31 Model Law.

21. Redfern & Hunter at para 9.114; ibid, Capper at p. 117ff.

22. See note 70 in Arthur, note 1 above. See generally in relation to the new uniform domestic arbitration legislation, Commercial Arbitration in Australia, Doug Jones, 2nd ed., Thomson Reuters, 2012.

23. Doug Jones, pp9, 18-19.

24. Doug Jones, see notes 22 and 23; and see note 2, The Hon. P. A. Keane.

Editor’s Note: This article appeared in the most recent edition of the Victorian Law Institute Journal (November 2013 87 (11) LIJ, p.40. It is published courtesy of the Law Institute Journal.

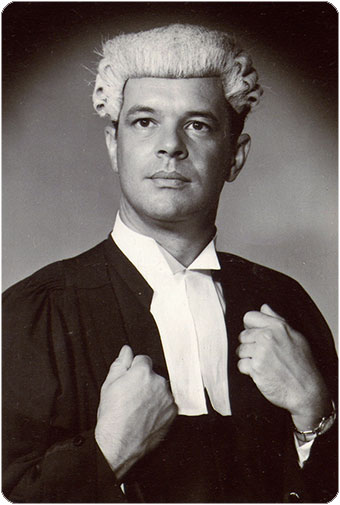

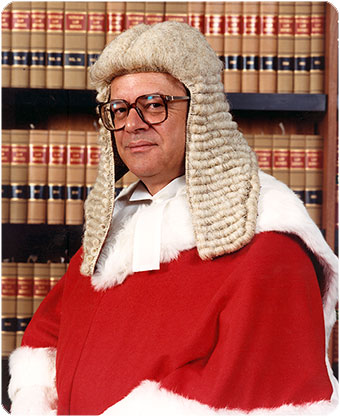

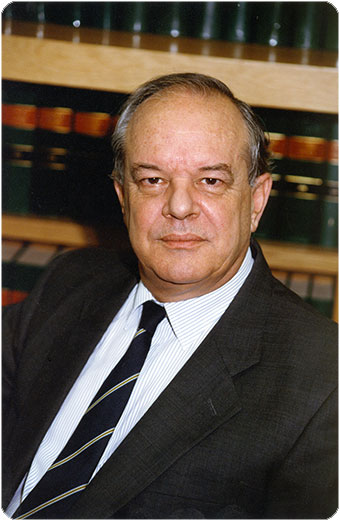

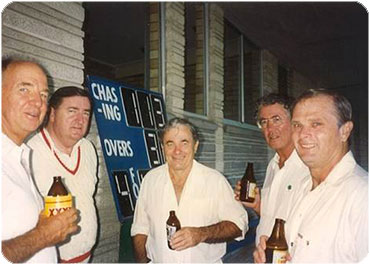

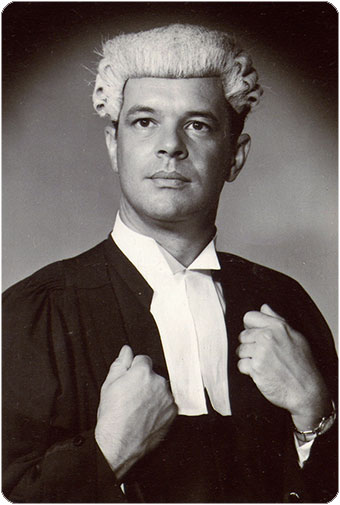

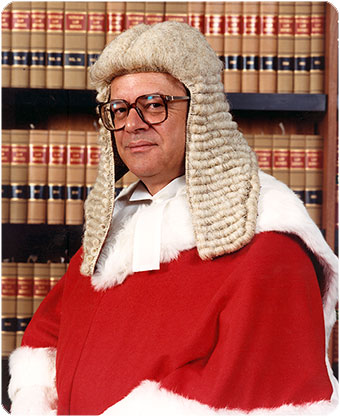

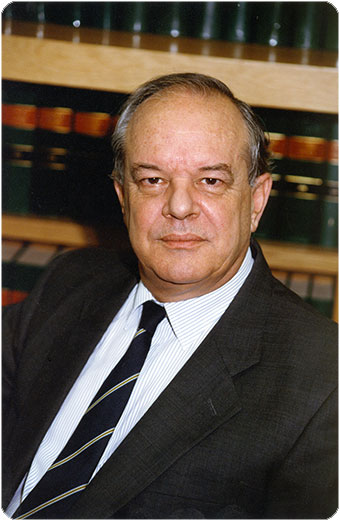

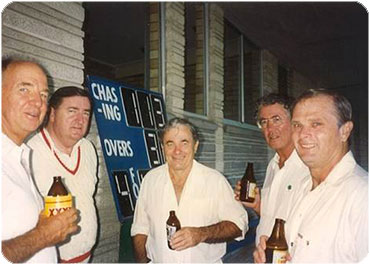

23.9.1936 to 7.10.2013

Bruce McPherson was a great judge. In twenty years’ time, barristers will still cite his judgments for their lucid and authoritative statements of principle; that is something that cannot be said about most of his contemporaries on the Bench. He was also a great scholar: he wrote the leading Anglo-Australian text on the law of company liquidation, a history of the Supreme Court of Queensland and his magisterial work, “The Reception of English Law Abroad”. And, through his work on Queensland’s Law Reform Commission, he was responsible for the “Trusts Act”, and Queensland’s most successful and longâstanding piece of law reform, the “Property Law Act 1974”.

But it is not McPherson the judge or the scholar or the law reformer that I wish to call to mind now. In the journal of the Bar, it is appropriate to recall McPherson QC, the barrister. It is fitting to do so, notwithstanding that, because he was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1982, the vast majority of barristers now in practice never saw McPherson at work on their side of the Bar table.

But it is not McPherson the judge or the scholar or the law reformer that I wish to call to mind now. In the journal of the Bar, it is appropriate to recall McPherson QC, the barrister. It is fitting to do so, notwithstanding that, because he was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1982, the vast majority of barristers now in practice never saw McPherson at work on their side of the Bar table.

Within Roberts and Kane, the firm of solicitors in which I was articled, McPherson QC was regarded as a legal wizard. We went to him with the most difficult matters. I had the great good fortune to instruct him in a number of these difficult cases, and quickly came to realise that McPherson QC was a model of what every barrister should aspire to be: diligent, energetic, selflessly dedicated to his client’s cause but able to remain sufficiently detached to provide candid assistance to the court, a master of the facts in the brief and the relevant law, courteous and courageous.

His opinions were models of learning and lucidity. They were beautifully written; always a joy to read. There was authority for every proposition, but never an anxious display of knowledge for its own sake; and always an appeal to principle rather than to rules for their own sake.

In his arguments in Court, he never allowed the citation of authority to obscure the clarity of his appeal to principle. His ability always to craft his arguments, so that they contained the clearest statements of principle and proposed the most reasonable solution to the problem at hand, characterised his advocacy.

In his arguments in Court, he never allowed the citation of authority to obscure the clarity of his appeal to principle. His ability always to craft his arguments, so that they contained the clearest statements of principle and proposed the most reasonable solution to the problem at hand, characterised his advocacy.

His example inspired all who saw him, and fostered the development within the Queensland Bar of the modern conversational style of advocacy with which all members of the Bar are now familiar.

Just as in the field of criminal advocacy, Casey and Brennan inspired Cuthbert, Sturgess and Spender who, in turn, inspired others, and so left the legacy of a cohort of criminal barristers which is, to this day, the equal of any in Australia, so McPherson and his able contemporaries inspired the subsequent generation of civil advocates.

McPherson QC, and his cohort of brilliant rivals, made a vital contribution to the improvement in the quality of the work of the Supreme Court. It was in this era that the Queensland Bar shook off the torpor and genteel poverty of the 1950s and 1960s. The Bar flourished and the Supreme Court became a better Court because of the quality of the assistance it received in difficult civil cases from McPherson QC and his gifted colleagues at the Bar.

McPherson QC and his able contemporaries helped to bring the quality of the work of the Supreme Court of Queensland to a stage of development where it is adorned by judges whose ability is second to none in the federation.

McPherson QC and his able contemporaries helped to bring the quality of the work of the Supreme Court of Queensland to a stage of development where it is adorned by judges whose ability is second to none in the federation.

Through all this, McPherson QC made a crucial contribution to the elevation of the esteem in which the Queensland Bar is held by the Australian legal profession in the other States.

For these reasons, it is fitting that every member of the Queensland Bar, even those who never saw McPherson QC in action, should remember that our Bar and our Courts are stronger and better institutions because of his time with us. And we should be grateful.

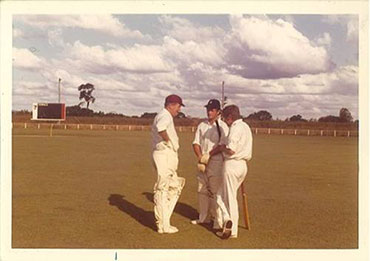

Photos provided by the Supreme Court Library.

The Hon Justice Patrick Keane,

Justice of the High Court of Australia.

The Queensland Bar has, over the years, produced many who have sought to turn their forensic skills to political advantage and to obtain high office. Senator James Drake succeeded Alfred Deakin as Commonwealth Attorney-General. Before Peter Connolly was a judge, he had one term as the member for Kurilpa in the Queensland State Parliament. The James Dean of Queensland politics, T J Ryan, became Attorney-General, then Premier, before dying in a Barcaldine hospital at the age of 45.

There are many others: Sir James Killen, John Greenwood, Cameron Dick and Matt Foley have all made their mark.

D espite the many who have conducted successful political careers, until this year, no member of our Bar had held the office of Commonwealth Attorney-General since Sir Littleton Groom KC mishandled an attempt to expel foreigners and was forced to resign in December 1925.

espite the many who have conducted successful political careers, until this year, no member of our Bar had held the office of Commonwealth Attorney-General since Sir Littleton Groom KC mishandled an attempt to expel foreigners and was forced to resign in December 1925.

Our new Commonwealth Attorney-General, the Hon. Senator George Brandis QC, has taken up that role, along with the title of Minister for the Arts, following the Coalition’s victory at the polls a few months ago. Senator Brandis comes to the post after 12 years as a Senator for Queensland. He took up that post in 2001 when a casual vacancy arose and lured him away from a successful practice at the private Bar, acting in large commercial matters.

In those 12 years, the Senator has drawn attention both for his capacity to turn his skills as an experienced counsel to devastating use in parliamentary committees, and for his ability clearly to articulate political arguments in debates both in parliament and on the airwaves.

Apart from his role as the first law officer, the new Attorney takes on the significant role of overseeing the nation’s intelligence agencies. Australia is involved in some of the most technologically sophisticated intelligence gathering operations the world has ever seen. Those of us who know him well allow ourselves a wry smile at the thought of the Attorney being confronted with so much technology. This is, after all, the man who, when once told by Phillips Fox’s IT Manager that their Macs could not understand files created on his PC, was heard to yell in frustration: “Well who the *#$% is Max and why isn’t he in this meeting?!”

A less than brilliant pedigree with technology aside, the Senator brings with him to the role a deep sense of the importance of the rule of law and, because of that, a commitment to the law’s orthodoxies; things which time in practice at the Bar instil. Judges should be appointed because they are highly suited for the role, and not to achieve some political ideal. The judiciary and the executive should accord each other respect and, when the occasion arises for criticism, it should be couched in appropriately respectful terms.

As an old friend, my view will rightfully be regarded as biased, but I think that we have every reason to be confident that our colleague will make an outstanding contribution at the interface between law and politics in our nation.

Nick Ferrett

David Ross Hall ceased being the President of the Industrial Court of Queensland on 4 October 2013. He had served as the President of the Industrial Court of Queensland from 2 August 1999 until 4 October 2013. This period of over fourteen years made him one of the longest serving Industrial Court Presidents since the Court’s inception in 1961. His appointment as President of the Industrial Court was not his first appointment to a bench. Between 1992 and 1993 he served on a full time basis as a Deputy President of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission but relinquished that role (but not the commission) on 1 March 1993 to become the Chief Industrial Commissioner of the Queensland Industrial Relations Commission, which position he held until his appointment as President of the Industrial Court.

I first came to know David when he was employed as a tutor in the faculty of Law at the University of Queensland. He was my tutor in Contract Law and later became my lecturer in Commercial Law and then in Industrial Law. He was an excellent lecturer with an ability to explain legal concepts in an easily comprehensible way. His lectures were peppered with references to villainous defendants known as “sly and simple” and absconding miscreants who “hit the toe”. During his academic career he wrote articles for the University of Queensland Law Journal and the Australian Law Journal.

I became actively involved with David when we co-authored a book entitled “Industrial Laws of Queensland” which was an annotation of the then Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1961 and the Wages Act 1918. We commenced the task of writing the manuscript in about 1975 and completed it some six years later. It was a massive task which involved reading all of the reported industrial cases in Queensland commencing with volume 1 of the Queensland Industrial Gazette which was first published in 1916. At the time of the book’s writing industrial and employment law was completely different in its practice to the way that it is practised now. At that time lawyers hardly ever set foot in the Queensland Industrial Commission (then known as “The Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Commission”) and appearances were mainly confined to the Industrial Court of Queensland. Queensland awards and the Queensland Industrial Act dominated employee entitlements and the jurisdiction of the Queensland Industrial Commission was jealously guarded against intrusions from its federal counterpart, the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. There was no readily identifiable industrial bar in Queensland as compared to New South Wales and Victoria where industrial law specialists were well known. David Hall would have been the go to lawyer for industrial issues in Queensland at this time.

About the time of the publication of the second edition of Industrial Laws of Queensland David gave up his full time academic career to pursue a career at the bar. Surprisingly I was not in many cases in which he was involved although we were both junior counsel (he for the Commonwealth of Australia) in cases in the High Court of Australia which arose out of the mid-1980’s industrial dispute in the Queensland electricity industry known as the “SEQEB dispute”.

One case that I do recall with some clarity is a matter in the Federal Court of Australia heard before Justice Peter Gray who has since retired. Justice Gray was then relatively newly appointed to the Federal Court having enjoyed an outstanding career at the Victorian Bar and was one of those industrial law specialists that I have referred to above. The case itself involved a prosecution under what was then section 5 of the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth.). Basically the allegation was that my client, a meat processor, had failed to engage former employees because they were members of a particular union. These days we would categorise such conduct under the heading of freedom of association.

David appeared for a number of the former employees although the prosecution itself was in the name of the particular union. I was lead for the first part of the proceedings by a Sydney junior counsel who had extensive experience in the meat industry. David called his first witness who was one of the former employees. After this witness gave his evidence-in-chief he was then cross-examined for about two and a half days by the counsel leading me. At the end of the cross examination there was little if any re-examination and David asked for the witness to be excused. Justice Gray as a courtesy turned to the counsel leading me and asked him if he had any objection to the witness being excused. Counsel said that he would prefer the witness not to be excused because there may be further questions he might need to ask. That comment drew the acerbic rebuke from Justice Gray “I doubt it”.

David Hall performed his duties as President of the Industrial Court in an exemplary fashion. His decisions were usually succinct and delivered not long after the date of the hearing. He was courteous and ensured that those who appeared before him, particularly litigants in person, could leave his courtroom knowing that they had been given a fair hearing.

The writer understands that David Hall’s health has suffered and I hope with his retirement he can fully recover to his former robust self

Ken Watson

The annual Bar Football Challenge Cup was again combined with the Sports Law Conference held in Sydney on the weekend of 21st September 2013. Among the topics for the Conference, hosted by Supreme Court Justice Geoff Lindsay, were current issues around anti-doping and when contact in sport can be considered to be a crime.

The actual Challenge Cup was held at St Andrew’s Oval (University of Sydney), with Queensland looking to defend their title won in Victoria in 2012. Unfortunately that was not to be as NSW were worthy winners, being able to field two strong sides for their matches with Queensland and Victoria.

In the first match Queensland, captained by Johnny Selfridge, overcame Victoria winning 2-0 with Lee Clark & Michael Hodge scoring the goals. Best and fairest gong went to Guy Andrew for Queensland, whilst the game was refereed by John Marshall SC from Sydney.

Playing back to back in the heat was too much for Queensland who had to then back up to play NSW immediately thereafter, it was a one sided match with NSW winning 4-0. The reality is that NSW were very convincing winners, irrespective of some of the groans from aging Queenslanders. If not for Dan Favell’s (best & fairest) heroics in goal, it could have been more.

Whilst the entire team gave their everything in the searing heat, special mention must go out to Dave “Chesty” Chesterman for his unselfish running and total commitment.

NSW then won again comfortably over Victoria, running out a 6-1 victory to claim the “Tri-States Champions” title in 2013.

NSW then won again comfortably over Victoria, running out a 6-1 victory to claim the “Tri-States Champions” title in 2013.

The Conference also raised $2100, which was donated to Camp Quality to help a child newly diagnosed with cancer to attend a Family Camp.

Queensland would like to show our appreciation to our colleagues from Victoria and NSW for a fine tournament, particularly Anthony Lo Surdo SC (NSW) and Anthony Klotz (Victoria) who both go to extreme lengths to assist in organising the event.

Never mind it’s back to Brisbane next year when the Queenslanders will surely be looking to wrestle that coveted title back on home turf!

Johnny Selfridge

Barrister

Under the UCPR, disclosure, both between the parties and from non parties, is primarily limited to documents directly relevant to issues identified in the pleadings: r 211(1)(b) and r 242(1)(a) UCPR.

The purpose of this article is to identify, notwithstanding the proscription contained in r 211(1)(b) and r.242(1)(a) UCPR, means by which disclosure may be obtained of policies of insurance, where the issue of a defendant’s entitlement to indemnity is not raised in the pleadings and the insurer(s) are not parties to the proceeding.

Disclosure might be sought to identify whether a defendant to the proceeding is entitled to indemnity in respect of the loss or damage claimed in the proceeding, or part of it. There may be good reasons why such disclosure is needed — and needed early in the proceeding — for instance where a defendant is impecunious and the question whether it is entitled to indemnity will determine whether there is a point to pursuing the litigation.

This article first addresses the basis for orders for further disclosure of insurance policies which might be made against parties to the proceeding, before turning to consider orders for disclosure of insurance policies that might be made against insurers who are not parties.

Orders for further disclosure against parties

There is authority of the Queensland Supreme Court that disclosure may be ordered against a party, where what is sought are insurance policies in the possession or under the control of the party: Company Solutions (Aust) Pty Ltd v Keppel Cairncross Shipyard Limited (in liq) & Ors [2004] QSC 379; Lampson (Australia) Pty Ltd v Ahden Engineering (Aust) Pty Ltd [1999] 2 Qd R 252.

Orders for further disclosure of policies of insurance have been made, even where the existence or otherwise of insurance is not in issue on the pleadings, on the footing that r 223(4)(a) (and its predecessor Order 35 Rule 14) gives the Court power to do so where “there are special circumstances and the interests of justice require it”.

In Company Solutions (Aust) Pty Ltd v Keppel Cairncross Shipyard Limited (in liq) & Ors Douglas J made an order that the company disclose a copy of the policy pursuant to r.223 UCPR. His Honour said at [8] – [9]:

“In those circumstances it is also appropriate to order that the policy be disclosed to Company Solutions. The question of the cover provided by the insurance policy is not in issue on the pleadings between it and Keppel Cairncross but it is highly important to the practical issue whether that litigation should proceed. In Lampson (Australia) Pty Ltd v Ahden Engineering (Aust) Pty Ltd [1999] 2 Qd R 252, 256-257 Moynihan J said:

‘The test of direct relevance introduced by O. 35 r. 4 replaces the previous rule which required discovery of indirectly relevant documents which ‘might lead to a train of inquiry’; this being the test stated in Compagnie Financiere Et Commerciale du Pacifique v Peruvian Guano Co. Under this discovery regime an affidavit of discovery was conclusive unless the existence of other discoverable documents could be established or it could be demonstrated that documents had been excluded under a misconception, Mulley v Manifold. In this context O. 35 r. 14(4)(a) gives power in the circumstances there specified to order the disclosure of documents beyond those directly relevant to the issues in the cause or in the circumstances contemplated by subr(4).’ (My emphasis.)

Coincidentally that case also dealt with an application for disclosure of an insurance policy to assist one insurer to engage in a mediation knowing whether or not it could look to co-insurers for contribution. The situation here is that neither Company Solutions nor Mr Pavlic now know whether it is worth pursuing Keppel Cairncross further. It may be true that they can prosecute their claims to finality and then discover whether any judgment against Keppel Cairncross is valuable. It was also submitted that they could fund the liquidators to test whether the policy covered the company’s liability. Neither solution is commercially realistic where the parties do not know whether it is worth pursuing a claim based on the policy.”

Douglas J said it was decisive that until disclosure of the policy was made, the parties did not know whether it was worth pursuing the claim and that disclosure of any policy would facilitate the just and expeditious resolution fo the real issues in the proceedings at a minimum of expense consistent with r 5. His Honour said (at [10] — [11]):

“That seems to me to create special circumstances where the interests of justice require such an order and where the overriding philosophy of the rules suggests that the order would facilitate the just and expeditious resolution of the real issues in the proceedings at a minimum of expense; see r. 5. As Pincus JA said in Mercantile Mutual Custodians Pty Ltd v Village/Nine Network Restaurants & Bars Pty Ltd [2001] 1 Qd R 276, 283 at [10]:

‘The former inflexible approach to applications for further discovery … is no longer necessarily appropriate, under the current disclosure system, and because of the notions expressed in r. 5 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules. If it appeared, for example, that an order for further disclosure would be likely to ‘facilitate the just and expeditious resolution of the real issues’, that would enable and perhaps require the making of such an order.’

Where, as here, the form of the policy is relevant to the application pursued by Mr Pavlic, is of great practical relevance to Company Solutions for the further conduct of its role in the litigation, there is no doubt that the insurance policy exists and is in the possession of Keppel Cairncross, it seems to me that there are special circumstances and the interests of justice require the disclosure of the document.”

Similar considerations arose in Lampson (Australia) Pty Limited v Ahden Engineering (Aust) Pty Limited [1999] 2 Qd R 525 where Moynihan J considered the circumstances in which O. 35 r. 14(4)(a) Supreme Court Rules gave power to order disclosure of documents beyond those directly relevant to the issues in the proceeding.

The rule permitted an order for disclosure to be made only if there were “special circumstances and the interests of justice require it” or if “there is an objective likelihood that … the duty to disclose has not been complied with…”. His Honour said (at 257):

“The interests of justice will obviously vary according to the circumstances of the case and will often involve the balancing of competing considerations. … The material founds a conclusion, supported by experience, that the mediation process will be enhanced if HIH embarks on it knowing whether or not it can look to co-insurers for contribution. On the other hand it has not been demonstrated that Ahden would suffer any particular disadvantage by virtue of disclosure. In the circumstances the disclosure sought is justified.”

Orders for disclosure against non parties

The first step to seeking disclosure of relevant policies of insurance from an insurer who is not a party to the proceeding would be to serve the insurer with a notice of non party disclosure.

If (as is likely) the insurer objects to production of the documents pursuant to r 245, it will be necessary for the party seeking disclosure to apply pursuant to r 247 for an order lifting the stay over the notice.

It is contended below that there are two bases that might be advanced at such an application as to why the stay should be lifted and disclosure made by the insurer.

First, the Court has power under Rule 247(2) which is arguably analogous to the power under r 223(4)(a) which is examined above. Rule 247(2) provides that on the hearing of an application about an objection to a notice of non party disclosure, the Court may “make any orders it considers appropriate”.

That power is itself in terms of wide compass. It is, of course, to be read together with r.5 UCPR. It is contended that it would be consistent with r.5 UCPR for the power to be available in circumstances such as those considered here, where disclosure of any polices would potentially lead to savings of Court time and parties’ resources.

This is because if the plaintiff were not able to satisfy itself by this process as to the availability of insurance cover, and thus as to the utility of proceeding with the action, it would be forced to proceed to have a proceeding set down for trial and proceed to enter judgment, perhaps in the absence of any representation from an impecunious defendant.

It would then have to embark upon a process of seeking to enforce the judgment and perhaps having to fund a liquidator to pursue indemnity against an impecunious defendant’s insurer.

It would be far more economical (for the parties, and for the savings of Court time) for a non party insurer of a defendant to disclose any policies caught by the terms of the notice of non party disclosure served upon it.

An alternate means by which access might be obtained to insurance policies held by non party insurers might be to contend that the documents caught by the notice of non party disclosure should be ordered to be produced in the Court’s inherent jurisdiction. The Supreme Court has inherent jurisdiction to order “equitable discovery” or “a bill of discovery”. Its power to make such orders is preserved by r 255: Wilkinson v Wilkinson [2009] QSC 191 at p 1-6.

The power was exercised in Wilkinson v Wilkinson, where Douglas J made a pre-litigation order for disclosure of documents evidencing compliance (or otherwise) with an agreement to compromise proceedings.

The agreement did not include any mechanism by which the respondent would advise the applicant that the terms had been carried out. The application was made approximately five and a half years after the deed was executed.

The applicant also sought (and was granted) leave to issue interrogatories. In granting the relief sought, Douglas J said:

“The applicant’s legitimate concern is that it has not been established that the respondent has meet her obligations under the deed. The applicant’s rights may be affected if this issue remains unresolved by the time of the expiration of any limitation period arising under the deed, whether it be a six year period or a 12 year period. They may also be affected by the prospects of survival of her mother. Although there is no evidence that her health is poor, the respondent is 85 years old.

In those circumstances, there is a distinct possibility that, if the terms of the deed have not been complied with, the applicant may have a right of action in damages but one which she is not presently in a position to institute because of lack of information about whether or not the obligations imposed on the respondent have been met by her. It is that situation which has led to this application.”

His Honour granted the relief sought on the basis of r.250 UCPR, “which permits the Court to make an order for the inspection of property if the property is property about which a question may arise in a proceeding.” (at 1-4). His Honour identified a further basis upon which the application could be granted (the right to seek a bill of discovery) at 1-6.

It is contended that this might be an alternate basis for seeking disclosure from an insurer who is not party to the proceeding of policies indemnifying a defendant for loss or damage claimed in the proceeding.

By David de Jersey

As the nature of practice at the bar changes with greater use of alternative dispute resolution and changing financial climates, advocacy experience doesn’t come as easily as it once did. While one may regard the effectiveness of one’s advocacy style as reflected by the workflow, there is no doubt that advocacy style is in a constant state of evolution. Over time, every advocate develops their own particular approach to structuring an argument, as well as idiosyncrasies and mannerisms which, while they may be endearing to some, may be irritating to others, particularly those the advocate is seeking to persuade.

While books and papers on effective advocacy are an important tool to a barrister in developing an effective advocacy style, they of course cannot serve as a substitute for experienced advocates and members of the judiciary observing and commenting on how you present both your written and oral argument. The ABA Appellate advocacy course serves to do just that by placing the performance of the participants, both in terms of the written and oral presentation of a mock case, under a magnifying glass and having both members of the judiciary and experienced silks observe and comment on the performance. While the process sounds daunting it is one worth undertaking to assist a barrister to further develop essential skills focussing on the strengths of one style and discarding less effective methods and perhaps annoying habits.

The Australian Bar Association introduced the appellate advocacy course in September 2012 apparently after some urging by some members of the judiciary who identified a need for some barristers to improve their skills when appearing before them in appeals. Such an improvement was necessary to assist the courts to meet growing case management of appellate proceedings.1

The appellate advocacy course for September 2013, took place in Sydney in the Federal Court. The barristers attending the course varied in seniority from middle Bar to Silks from a number of different States and Territories, with one barrister attending from New Zealand. A wealth of talent was gathered from the judiciary from both Federal and State Courts as well retired members, including the Honourable Michael McHugh AO QC, formally of the High Court. Justice Fraser and Justice Martin were amongst those who generously gave up their time to sit as Judges, as did Mr Michael Copley QC who attended to assist in the coaching of the advocates. Kelsey Reisman also provided support to all attending and ably kept the show on the rails.

The course participants attending the course were briefed with a mock case that involved seeking leave to appeal from a judgment in the Federal Court and then appearing at the appeal. Prior to attending for the three day course, each participant had to provide written submissions for one party for both the leave to appeal and the appeal. Inevitably you find that it requires more time to prepare the submissions than you have set aside. Juggling that with your practice results in a few late nights but it ensures that participants extract the most they can out of the course by being well prepared and having given thought to the problem. As you receive feedback on both your written and oral advocacy it also serves to highlight the points of distinction between them in the presentation of a case and the differing focal points.

The ABA course operates on the premise that the best way to test and improve skills is by placing advocates in the position of arguing a mock case. Experience indicates that is the most effective method. Given the focus of an appellate advocate is solely on persuading three members of the judiciary as to the correctness of your client’s position, the ABA sought the involvement of the judiciary to sit as Judges to hear the argument. Asking Judges to explain what they find persuasive and why, and what they find distracting or lacking utility, informs the advocate’s task of persuasion.2 Senior Silks sit in and observe the participants and provide more detailed feedback. Thus participants have the benefit of feedback from both the Bench and the Bar who provide a healthy cross section of commentary. This approach avoids the notion that there is a “one size fits all” advocacy style and helps advocates focus on their own individual style and how to improve that individual style when seeking to persuade to the court. In addition, one has the benefit of appearing against advocates from all over Australia and observing their techniques as well as having the benefit of the commentary in relation to their style.

Advocates are then paired up and appear generally before a Judge or retired Judge. After receiving comments from the relevant judicial member, each advocate then has a coaching session with the two silks who had been sitting observing the argument. They provide feedback while playing back a DVD recording of the performance. The coaching session dissects all aspects of your performance, including not only the structure of the argument, but voice projection, eye contact, hand movements, use of written notes, reference to cases and the posture at the lectern. While such a process is inevitably confronting for the participant, the comments are presented in a constructive, albeit direct manner focussing on your strengths and weaknesses and providing suggestions as to how you may improve your performance. It is particularly helpful to be made aware of habits that your are not conscious of when you are speaking which may be distracting to the bench you are seeking to persuade, as well as your more persuasive techniques. In the afternoon session, the same process is undertaken with a different opponent and Judge, but each participant must argue for the opposing party to the one that they represented in the morning.

The first day begins and ends with comments from the Judges and Coaches. Mr Todd Alexis SC, chaired the three days. On the first day the Honourable Justice Beazley AO, President of the New South Wales Court of Appeal and the Honourable Justice Allsop AO, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia, provided an overview of the Court’s expectations of appellate advocates and how they may be met. Mr Phillip Greenwood SC also provided an outline of what the course seeks to achieve. The day ended with a panel discussion consisting of members of the judiciary and some silks on “Engaging the bench and Engaging with the bench”.

On the Saturday the focus was on the appeal. Again, each participant had to argue both sides of the argument, one side in the morning and one side in the afternoon, before a bench of three. The bench generally consisted of a Judge sitting with two silks. Time limits were provided for arguments and were enforced. Again after the finish of the appeal, comments were made by the Judge in terms of the performance and arguments presented. The Judge then left the room and the two silks who had sat as part of the Bench then provided a coaching session.

Much thought has gone into structuring the course to ensure participants derive the greatest benefit. For instance, a participant must prepare an outline for leave to appeal for one party and an appeal outline for the opposing party so they are in a position to argue both sides of the argument. Separating the argument for the leave to appeal and appeal to separate days permits participants to experiment with some of the suggestions made on the first day when arguing the appeal.

On the last day, participants are divided into groups and a judge or retired judge who has reviewed the written submissions of each person in the group provides comments on each person’s submissions. Participants are given the opportunity to rewrite their submissions over the weekend prior to the review if they wish.

The course is not for the faint hearted and requires significant preparation, which would warm the cockles of Justice Fryberg’s heart. Our profession is not however one for the faint hearted. As with all of these courses you get out of it what you put in. All of the Judges and the silks who act as coaches come well prepared and are ready to put advocates under pressure. The quality of those running the course and those judging the arguments tends to steel the focus of all who are participating. It is however a case of providing a forum for a barrister to ask the questions that you always wanted to ask after presenting an argument but, of course, can’t ask.

The course is not all work. On the Saturday night, participants and those undertaking the training are invited to attend a dinner. A fabulous Italian restaurant was chosen and a lot of fun was had.

Every child wins a prize and each participant is sent home with a memento of their performance. Each participant is given a USB stick with the video of his or her oral performance to take and review at your leisure. It may have the added benefit of providing a cure for insomnia.

The course is well worth doing. I would suggest it is more worthwhile for barristers who have been in practice for more than five years and have undertaken some appeals. It inevitably takes far more time away from your practice than you have set aside and having signed up to the course, you wonder, when you are preparing written submissions late at night, why you did this voluntarily. But of course, advocacy is one of the key skills of the Bar which separates us from the rest of the profession and like every skill, the more you work at it the more effective you are as an advocate. Even if you walk away from the course with nothing more than reassurance that you are on the right track and suggestions of some subtle changes which will prove that the persuasiveness of your style, that is an enormous benefit.

So if you get a call from the charming Stewart QC with his dulcet tones enticing you to undertake one of the courses, I would encourage you to take up the gauntlet. At the end of the day our task is to persuade and the opportunity to have those who listen to us or appear against us commenting on whether we achieve that goal cannot be overvalued.

Sue Brown QC

- As to the genesis of the course see C P Shanahan SC “Appellate advocacy: A new course for barristers” (2013) 36 ABR 310

- Appellate advocacy – a new course for Barristers, CP Shanahan SC, (2013) 36 ABR 310 at 312

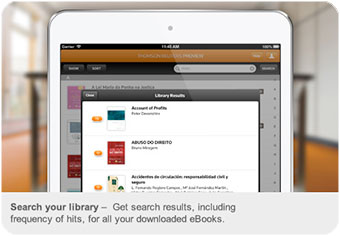

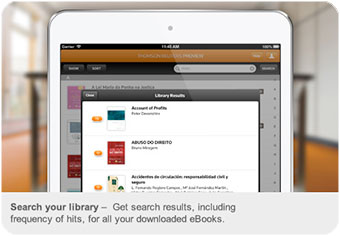

May I first express my gratitude to them, for providing me with a short term subscription which has enabled me to see first hand what they have to offer, so that I could be better able to prepare this article.

To start with, I have to emphasise that I don’t have the easy familiarity with this system that I had with Red due to having used Red by LexisNexis for most of this year. I say this because a reader who is more familiar with ProView, might well have identified some shortcuts which I will miss, only having had a short time to familiarise myself with it. For that, I will apologise to Thomson Reuters and yourselves, in advance.

ProView is the Thomson Reuters equivalent to the LexisNexis Red system about which I wrote in July. ProView is used either as a stand alone service or in conjunction with Westlaw AU, their Case Base research platform which has been available and widely used for many years. Red is similarly used in conjunction with LexisNexis Case Base, about which I made reference in the earlier article.

This article must start by confronting the elephant in the room, namely that many of us are reluctant to change old habits, wean themselves away from having hard copy material and not simply move to a digital or online alternative but gain confidence in using it.

Let me observe what is happening with newspapers. These are fast disappearing in their traditional printed form. We are being given tempting offers of digital or online subscriptions. which are cheaper and far more versatile than what the newsagent charged for the old “paper”. They don’t need a delivery person to throw it through a window of our house in the early morning. The e-paper arrives on our Tablet or computer, without fail, very early each morning. We can read it whether we are in Brisbane or Las Vegas. It doesn’t care where we are, which is one of the wonderful benefits of the digital age. Similarly, doing online legal research only requires Internet access, and is independent of where we are in the world.

I believe that within a very short time, it will no longer be possible to buy the old style newspapers in any other form than by online subscription.

In exactly the same way, it is my belief that hard copy and loose leaf subscriptions for books and other legal publications will be joining the dinosaurs before very long. Therefore we must embrace the future in such a way that, as barristers, we can gain the same comfort and familiarity with it, that we have done for the traditional libraries with which we grew up.

How many of us still use a printed street directory rather than our in car or mobile phone GPS navigation system? Not many I suggest.

I was provided with short term access to 15 different publications, which included subscription loose leaf and traditional material ranging from Australian Civil Procedure (Cairns), to Internet and e-commerce Law, Business and Policy (Fitzgerald, Middleton and Clark) together with the digital versions for subscription services such as Queensland Civil Practice so that I could familiarise myself with how ProView works in my day to day practice.

I was provided with short term access to 15 different publications, which included subscription loose leaf and traditional material ranging from Australian Civil Procedure (Cairns), to Internet and e-commerce Law, Business and Policy (Fitzgerald, Middleton and Clark) together with the digital versions for subscription services such as Queensland Civil Practice so that I could familiarise myself with how ProView works in my day to day practice.

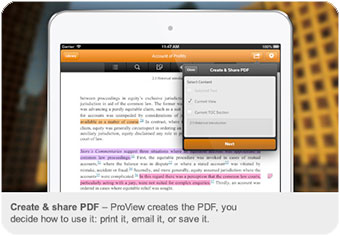

I believe that all barristers will already be comfortable using Adobe Acrobat to read Document Files (known as PDF’s). This format is a wonderfully simple and convenient way to read documents without losing any of the formatting, page numbering etc, that is usually lost when using other forms of document files.

It is a simple and comfortable transition from reading a PDF to e-reading a Thomson Reuters publication. The presentation to the person reading it, is in a PDF like form, albeit that it looks a little different to what you might be used to and has a lot more features than a traditional PDF. It is not actually a PDF I hasten to add.

The presentation of ProView between a computer and, say an ipad, is subtly different, but it is second nature to move between them. The controls are still there but may be at the top or at the bottom of the page, depending on the device that you are using. At the date of preparation of this article, the desk top version of the software was a little behind that available on Tablets, but they should be the same by the time this is published.

The opening page permits us to view all of our subscriptions in either columns and rows (as if sitting on bookshelves) or in a single vertical column. A mouse click changes from one to the other.

Rather than purchasing a hard copy of a title, be it a book or a loose leaf subscription, we can purchase a digital copy, which shortly after payment, appears in our ProView library. Before we can use it, we have to download it, a task which takes less than a minute. Being a subscription service, it is updated as long as we continue our subscription, so that we can be confident that we are referring to the latest law on our subject.

A click of the mouse over the title, quickly opens it. At the foot of the opening page are several options. To the left is a box which identifies the page number. Next to it are two arrows, allowing one to move forwards or backwards through the text. The balance of the foot of the screen contains a ‘slider’ which one can drag from one side of our screen to the other, thus advancing or retreating pages. In addition, by inserting an actual page number in the page box, one can immediately go to a particular page in that text.

There is a third method of changing pages, namely by using the vertical slider which appears on the right hand side of the page, ( much the same as with PDF’s) or by using the scroll wheel on your computer mouse to move that slider up and down. Scrolling can be set to limit movement to a particular page, or to scroll up or down any number of pages.

As part of your subscription, you can download a purchased publication onto your personal computer, say, in Chambers, as well as onto one or more Tablets (be they ipad, Android or Microsoft) and a fourth device such as a conventional laptop or another Tablet.

Once downloaded you can access it even if you are not Online. What I mean by this is that the e-books that you have purchased are actually stored on your Tablet or other device, so that even on an aeroplane in Flight mode or in a Court at Bullamakanka one can still access this material despite there being no Internet or mobile digital service available.

However, I offer a word of caution. Whilst these e-books are downloaded to our Tablet, laptop or whatever, in order to access them we need to be logged into the ProView program. The concept of ‘logging in’ is different to that associated with being ‘logged in’ on a computer. Rather, instead of ending a session in ProView by ‘logging out’, we simply turn off the Tablet, laptop etc’s wi fi or other connection to the Internet, so that next time we want to access our library we don’t have to log in again.

If you do log out, to re-enable your ProView service on the next occasion, you must have Internet access to first verify that you are who you say you are (ie, provide your user name and password). By not logging off at the end of your session, you can turn on your Tablet on the train or in a plane and all your library is available for you. Thomson Reuters suggest that users should rarely if ever actually need to log off, when using a portable device, which means that all your purchased library is immediately available on that device, whether or not you are in Internet range.

When not actually online, I have found that it is not possible to access the links to the footnotes to an e-book. I presume that they are not stored with the publication on our device, but are online.

I cannot emphasise too much the importance of ensuring that any portable device, such as a Tablet, ipad etc, is password protected so that if it is lost, no one else can access your material.

For the times that you need access to ProView and don’t have your own computer or Tablet, ProView is also available through any Internet connected computer in the same way that Westlaw AU is. It simply requires you to log on with your user name and password .

It will immediately be obvious, that actually logging on and off, with a foreign computer, is absolutely essential to the security of your work, as otherwise the next user of that device, can access your library and your work.

I have suggested to Thomson Reuters that the use of the term “log out” in relation to Tablets, is confusing. I would prefer a change of name to something closer to what it actually means, together with a pop up menu warning that if you hit this key, you will need to have Internet Access when next you wish to access your library. This “feature” was one that I found by accident when I tried to use my ipad after logging out in what I thought was the traditional way. As I was out of Internet range at the time, I was unable to log back in. So let this be a word to the unwary.

The second obvious benefit is that to which I referred in my previous article on digital researching, namely the “Search” function.

A search of my 15 titles for the word “bigamy” took 7 seconds to tell me that this term is referred to in five of them. Perhaps not surprisingly, several of them are contained in the publications dealing with the Evidence Act. I defy anyone to find even one of these references within 7 seconds.

The Search function need not be limited to one word but with some practice, can be refined by using a string of several words to summarise the intended focus of our search.

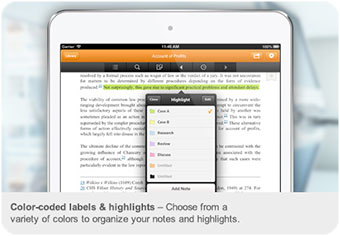

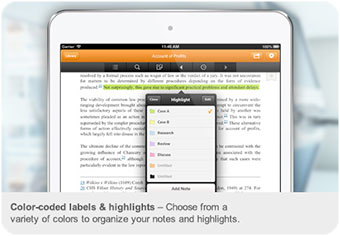

ProView allows us to highlight, add a note or share any parts of the text. This means that if we are working on a text at home, on our ipad or other device and want to continue where we left off when back in Chambers, we do not have to take our Tablet with us, as any highlights or notes are synchronised between our devices, when they are connected to the Internet. This does not mean that they have to be connected simultaneously, just that they are both connected at some stage before we next want to use the earlier material.

ProView allows us to highlight, add a note or share any parts of the text. This means that if we are working on a text at home, on our ipad or other device and want to continue where we left off when back in Chambers, we do not have to take our Tablet with us, as any highlights or notes are synchronised between our devices, when they are connected to the Internet. This does not mean that they have to be connected simultaneously, just that they are both connected at some stage before we next want to use the earlier material.

I have read several of the e-books whilst on the train and use the “note” function to tell me where I have finished, because I might use a different device next time I continue reading it.

Obviously, the use that we can make of this function is only limited by our imagination and the way we prepare and organise our material.

This has the additional benefit that we can prepare our work on our large work computer, then have it transferred without any input from ourselves, to our Tablet, to be used in Court.

Let me speak about noting the text for a moment. First, one uses the mouse and left mouse button to identify where we want to put a highlight or note (we are invited to do either, both or to copy that selection). We are given 7 different coloured note options. I am not going to give away all my trade secrets but I used to use different coloured “Post It Notes” for different types of information that I wanted to be able to quickly access in Court. Now, I can do this using electronic coloured notes which show a small icon to the side of the text to remind me of what colour note, I have made. There is a half arrow in the top left of the ProView screen which opens a box which sets out each annotation that I have made in that text, the highlighted text and the time when I made the note.

When using ProView on a browser, the time stamp initially shows some 15 hours out, but when used on a Tablet or computer using the installed progam, the time stamp is correct. This idiosyncracy will shortly disappear I am assured.

If we choose to highlight a passage of text, we can do so in one of a number of colours. When we uncover our highlights box on the left hand side of the screen, each passage of text is set out, with the requisite colour alongside it. If we click our left hand mouse on that passage in the Highlights box, we are taken back to the actual text, where, lo and behold, the chosen passage remains highlighted in the same colour.

Yes, I know. It is perhaps easier to have it demonstrated on your computer than it is for me to explain it. The real point is that we used to use different coloured highlights on our photocopies or loose leaf services but now we can do the same on our digital copies.

There are three differences. The first is that ProView permits us to have a list of our various Highlights or Notes set out according to their colour. Secondly, when we are finished with them, we can delete them and we have not damaged our paper version in doing so and thirdly, we can collate these notes and highlights according to their colour as I will explain.

In the Options box (top right hand side of the page, in the form of a cog), there is one called “Labels”. The purpose of this option, which is brand new, is that it enables the user to give a name to each of the various coloured labels. For instance, we could name them, “evidence”, “cross examination”, “legislation”, “amendments” or whatever we want. As we make our notes or highlights, we save them according to their character as legislation, evidence or the like. By then calling up our Annotations, we can filter them according to their colour, so that all notes made in any particular colour are listed. This is an excellent research facility. The labels which we have made, remain, whatever material we are looking at.

These notes are limited to the single publication that is open at the time so that those made by reference, say, to Cairns, are not available if we have the Federal Court Practice open. I hope that Thomson Reuters will in time, make all our history available, across all titles.

In the Annotations box, appears a choice of Displaced Annotations. This is a useful feature which stores annotations that we might previously have made in a section of a publication, where, during the updating process, that original section or passage has been deleted. These annotations are, necessarily, displaced, that is, they no longer belong to text, but they are not lost to us unless we decide to delete them.

This function, I suggest, is probably more useful than might be immediately obvious. I frequently refer to the Safety Rehabilitation and Compensation Act (Commonwealth). I keep that Act in several forms, one of which is the electronic annotated form published by Ballard some years ago, and I also keep the latest hard copy. This is festooned with stuck on pages of notes and names of authorities which I have found useful over the years. In many cases, the section or subsection of the Act to which they referred, has been amended or repealed but the notes are important to retain. There are times when a question arises under a repealed or amended section. The notes I have made could be digitally preserved under Displaced Annotations. With each edition of Ballard, I used to transfer over my notes. With this digital function, I could do this once and for all, with any of the Thomson Reuters subscriptions.

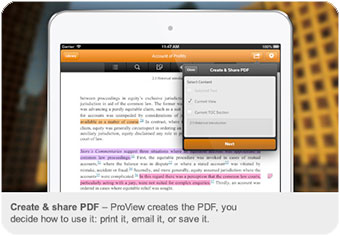

With updates to ProView, more and more titles are being provided with a “print” option, which allows us to print, for example, a marked or highlighted passage or our list of annotations. Like me, if you become familiar with using the system you will find little reason to have to use this feature, but it is there, if needed.

With updates to ProView, more and more titles are being provided with a “print” option, which allows us to print, for example, a marked or highlighted passage or our list of annotations. Like me, if you become familiar with using the system you will find little reason to have to use this feature, but it is there, if needed.

In addition, we can “copy” a highlighted or noted passage and import it into any other Word document, much as we do now, with material that we access on the Internet.

I am attempting to provide no more than a snapshot of what one can do with ProView. I found that, like Red, it is very easy to navigate around the various main functions.

I was offered, and availed myself of the opportunity of a free in person training session which I strongly recommend. This tutorial, gives you “L” plates from which to gain familiarity and confidence in using ProView.

Thomson Reuters offers an unlimited free online or in house training program. If you really want to become proficient in using ProView, I strongly urge that you book in for one or more formal training sessions and follow it up with regularly using the service. The more it is used, the greater our proficiency and confidence improves.

These sessions are invaluable and are worth repeating at intervals, as, with updates to the service, other features become available which might not otherwise be picked up. We all read the very comprehensive Release Notes that accompany and explain updates, of course!

There is a temptation to try to compare the relative merits of the two services, Red and ProView, but I am not going to. I think it would be unfair to both publishers to try to compare the two when I have been actually using Red in my day to day practice and therefore have a much greater familiarity with it.

Since receiving my online library, whenever I have asked questions or pointed out apparent glitches in ProView, I have received very timely and helpful responses and cannot fault the feedback. They have shown much interest in my suggestions for improvements to ProView.

If you look at the Release Notes to the October update of ProView, you will see that these have included significant enhancements to the Annotation management so one can be confident that it is being refined to better respond to our needs.

I have also enjoyed simply reading a number of Thomson Reuters e-books, for at its most simple, ProView gives you the option of purchasing from an extensive library from which you can research legal topics of interest. Of course I have only scratched the surface with the titles I have on loan, but I do commend their extensive library to you.

My strong impression is that both publishers are keen to hear from barristers as to what we want and what we are not getting. If we can identify helpful things that are not available there is a good chance of seeing them appear, a few months later.

One negative I have with ProView is that you can review your search history in any particular publication, but you cannot do this for more than one publication at a time. With Red, along the bottom of the screen, you can see what reference material you have recently used, and the specific researched areas, so that you can quickly move from one publication to another and back again without having to leave one publication and specifically open another or others. Don’t be surprised if ProView has this before long as it is too useful a tool not to have.

I do think that there are two fundamentally important reasons why barristers would consider ProView or Red. The two reasons are, the sure knowledge that our subscription material is up to date, without the need for countless hours spent updating loose leaf folder and the second, is the Search function. Each service provides these. No matter how familiar we think we are with Rules of Court etc, we may easily miss one reference to a particular issue, but Search will not miss a thing. If called upon at short notice to respond to an issue, when in Court, rather than trying to focus on what the Judge or our opponent is saying, whilst simultaneously combing through the Evidence Act or whatever, a click on Search will do the hard work for us, so all we have to do is glance at the results and bring up the appropriate reference.

There is a third important reason for joining this digital club, namely, the ease of having a large amount of material with us wherever we go, without having to break our back or contribute exorbitant funds to the next runway at Brisbane Airport.

I have said in relation to Red, that once one has gained both familiarity and confidence in using these facilities, we can throw away our loose leaf documents. Precisely the same can be said for ProView.

Conclusion

I am a strong supporter of digital online subscriptions and hope that through these two articles, I can encourage those who have misgivings, to appreciate that once you give yourself a little experience and become comfortable with them, these resources will become as familiar and useful to you in your day to day practice, as the traditional methods with which you grew up.

I thank Thomson Reuters for offering to make ProView available to me, for the purposes of preparing this article and for their feedback to my original draft.

*Images courtesy of www.thomsonreuters.com

Let us now praise famous men, and our fathers that begat us.

The Lord hath wrought great glory by them through his great power from the beginning.

Such as did bear rule in their kingdoms, men renowned for their power, giving counsel by their understanding, and declaring prophecies:

Leaders of the people by their counsels, and by their knowledge of learning meet for the people, wise and eloquent are their instructions:

Such as found out musical tunes, and recited verses in writing:

Rich men furnished with ability, living peaceably in their habitations:

All these were honoured in their generations, and were the glory of their times.

Jackie has told me that Bruce insisted upon a lunch-time funeral. He did not want the profession to be out of pocket on his account.

Bruce McPherson was born in South Africa on 23 September 1936 and died in Brisbane on 7 October 2013. He was, in his time, a university lecturer, barrister and Judge, an author, an historian, a reformer and above all, a husband, a father, a mentor and a friend. Jackie, Andrew, Fiona, Lachlan, Ewan and Malcolm, Bruce’s sister, Mary and his grandchildren, India and Ava have special claims upon him and his memory which the rest of us cannot share. We do, however, cherish our own memories of him as colleague, mentor and friend. We acknowledge the breadth and substance of his contribution to the public good, and the joy which we have derived simply from knowing him.