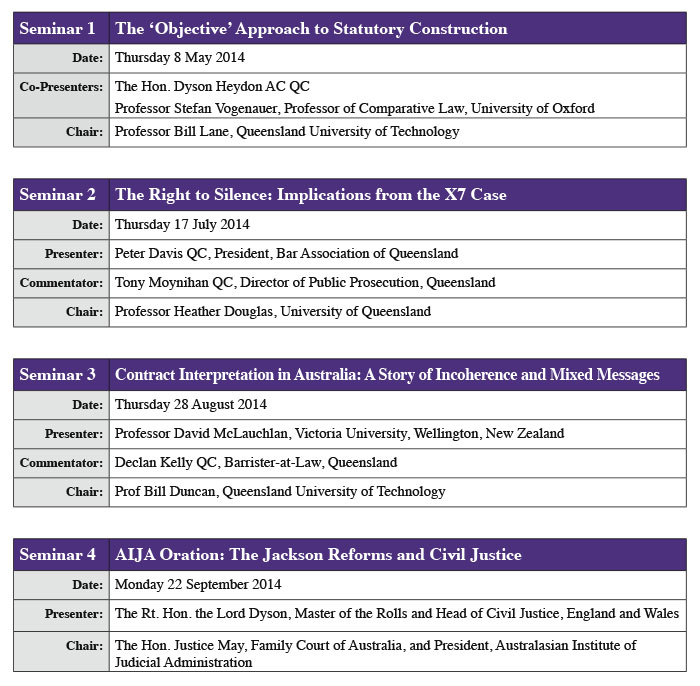

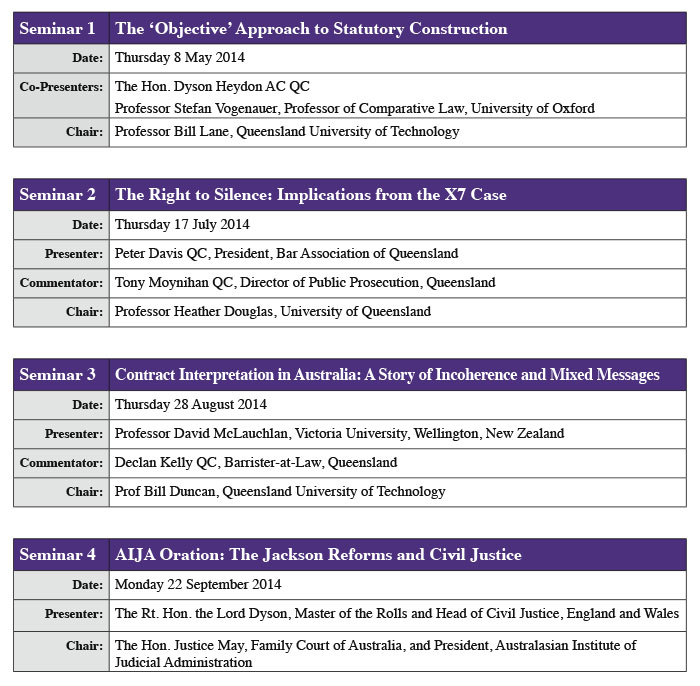

The Bar Association of Queensland, University of Queensland, Queensland University of Technology and Supreme Court of Queensland Library are pleased to announce the Current Legal Issues Seminar Series for 2014.

The seminar series seeks to bring together leading scholars, practitioners and members of the judiciary in Queensland and from abroad to discuss key issues of contemporary legal significance.

Described by the Hon Alistair Nicholson AO RFD QC, former Chief Justice of the Family Court of Australia, as having lead that court’s development in case management, judicial education and judicial administration it will be the international recognition and regard still held for that court’s standards in those fields that will be Neil’s enduring legacy as a judge.

Born in Toowoomba on 30 December 1944 Neil was educated at St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace and the University of Queensland from which he graduated in 1968. He was admitted to practice as a solicitor and to the partnership of Brisbane firm MG Lyons & Co in 1969.

A talented and successful lawyer Neil’s time as a solicitor and partner was marked by his conduct of many high profile cases particularly in commercial and corporate litigation. Despite an extremely busy practice, Neil demonstrated a continuing commitment to pro bono and other voluntary community work.

Neil served on many Queensland Law Society committees and from 1979 to 1980 was a founding member and Vice President of the Family Law Practitioners Association of Queensland. From 1978 to 1983 he was a member of the Family Law Council, a statutory body with responsibility to advise the Commonwealth Attorney General on matters related to family law.

On 7 February 1983 Neil was appointed as a Judge of the Family Court of Australia and on 30 June 1988 as Judge Administrator for Queensland and the Northern Territory. From 1996 judicial administration for New South Wales was added to his responsibilities. On 1 July 1999 Neil was appointed Senior Administrative Judge of the Court performing all of the judicial administrative functions formerly performed by the then recently retired Deputy Chief Justice. Neil was a natural leader through the power of his intellect and personality and his ability to engender in others loyalty and commitment to shared ideals. Equally, he was a fearsome adversary.

Neil became a Council member of the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration (AIJA) in 1989 and a member of the Board of that body in 1992. He served as its President from 1996 to 1998 and his contribution to the work of the AIJA in the development of best practices in Australian courts was recognised in his award in 2001 of Life Membership of the AIJA.

Neil demanded of those who worked for him and with him the highest standards of professional practice and integrity and for the whole of his professional life as both lawyer and Judge was committed to the training and education of young lawyers. His work with the AIJA was marked by his enthusiasm for and commitment to judicial education — including at a time when many were opposed to the concept.

Neil was a pioneer in facilitating and structuring judicial education programmes in Australia and internationally in domestic violence, gender equality; cross-cultural and indigenous issues and other social justice issues. He was appointed an Advisory Board Member of the United Nations Development Programme providing training and advocacy to promote social justice throughout the Pacific region of nations. He gave numerous presentations at Australian and international conferences including in the USA, the United Kingdom, Canada, the West Indies, Sweden, Brussels and New Zealand in case management and social context education programmes for judges.

Neil retired as a judge of the Family Court of Australia on 30 August 2006 after more than 23 years’ outstanding service to the Court, his community and judicial education both in Australia and overseas.

Upon his retirement Neil applied his keen intellect and the same level of commitment marking his judicial career to the dark mysteries of fly fishing; cattle breeding and husbandry; and farming. His meticulous attention to detail and passion for doing things well lead to him being regarded as in the top echelon of amateur fly fishermen in Australia. He maintained a lifelong passion for Rugby and sharing a good wine over a meal with family and friends.

Neil’s professional and career achievements were many and impressive. No less so was his loyalty and commitment to his many friends from all walks of life throughout Australia and throughout the world. His funeral was attended by those who had travelled from Europe and interstate and by current and retired Judges, farmers and panel beaters, the young and old.

Above all else, Neil regarded his marriage to Helen and his children, Eugenie, Jude and Daniel, and his grandchildren, as the most important thing in his life. It is a matter of considerable sadness to his family and his many friends that, his illness did not allow him the long and healthy retirement he deserved.

The courageous and selfless way in which Neil battled the illness that was to take his life was as impressive as it was unsurprising to those of us privileged to have known this man of rare quality and character.

As the Hon Alistair Nicholson said in concluding his eulogy of Neil “he was a fine judge and judicial leader and great Australian. We will not see his like again”.

Hon Justice Michael Kent

Chambers

2 December 2013

I completed the course in Brisbane in January 2013, after Michael Stewart QC ( it is fair to say) dragooned me into doing so. I am very glad he did. This piece sums up my experience of the course — the best I have encountered in my time at the Bar — for those of you interested in the small number of places still available.

The course concentrates on four aspects of advocacy essential to good trial performance- opening, examination in chief, cross-examination and closing. The course devotes one day to each of these disciplines.

The cohort of 42 participants is streamed into groups of six, of similar seniority, grouped by practice area.

The material with which each group is working is a “brief” in a passing off case. There are three on the applicant side and three on the respondent side. In the criminal stream the brief is to prosecute and defend a rape case. Counsel have to prepare their side of the case for hearing prior to the commencement.

Each morning, there are presentations and discussions by first class presenters, aimed at better informing one’s approach to the four tasks. My group had Nicolas Green QC on the theory of the case and opening, Justice K Martin (WA) on leading evidence, and Ian Temby QC on cross-examination. Not too shabby. And the coaches with expertise in voice, movement and impact were a revelation.

Each afternoon, each participant presents his or her 15 minute opening, 15 minute evidence in chief from the liability or damages witness, 15 minute cross-examination or 15 minute closing. This is all on-camera, in Court, with a Judge and opposing counsel. Also in Court are one or two further Judges, one or or two silks and the voice and impact coaches.

All the above are observing, with the video cameras rolling, so that after the task is complete, all can constructively critique what they saw by reference to the video. With the benefit of that critique, there is then an opportunity to do the task again, and a second video, and further coaching.

As I see it, the main idea behind the course is: “What we think and do is limited by what we fail to notice. Examine thus yourself from every side.”

The course allows a participant to see and hear himself or herself as the Judges do. We achieve a better appreciation of what we do, and fail to do, as we stand at the lectern in each of the four disciplines. We see what we sound like, what we look like, our mannerisms.

The ABA website describes this philosophy as being that “the skills of a barrister are best learned through a deep understanding of the relevant objectives for each performance task”.

However you describe it, the Course improves one’s effectiveness as an advocate and one’s comfort in the role. This really is a brilliant means of becoming aware of bad habits and how to eliminate them and perhaps to be pleasantly surprised about the things that you get right.

It is not all hard graft though, and the Course certainly builds an esprit de corps. At your table each evening you can expect good wine, food and conversation shared with Judges, silks and juniors from all over Australia, New Zealand, the UK and other parts of the Commonwealth.

Jeremy Sweeney

News, views, Practice Directions, events, forthcoming national and international conferences, CPD seminars and more …

Bar Conference 2014

The Annual Bar conference will be held from 7 to 9 March 2014 at the Sheraton Mirage, Gold Coast. The theme of the conference is “Tomorrow’s Bar Today” and will feature many prominent speakers, including the Hon Justice Gageler of the High Court, Lord Justice Moses of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, the Honourable Paul de Jersey AC, Chief Justice of Queensland, Professor John Carter Dr Stefan Hajkowicz from CSIRO Futures, Dr Hayley Bennett, Dr Craig Hassed and other prominent members of the judiciary, the bar and other practitioners.

The Annual Bar conference will be held from 7 to 9 March 2014 at the Sheraton Mirage, Gold Coast. The theme of the conference is “Tomorrow’s Bar Today” and will feature many prominent speakers, including the Hon Justice Gageler of the High Court, Lord Justice Moses of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, the Honourable Paul de Jersey AC, Chief Justice of Queensland, Professor John Carter Dr Stefan Hajkowicz from CSIRO Futures, Dr Hayley Bennett, Dr Craig Hassed and other prominent members of the judiciary, the bar and other practitioners.

The conference will be preceded by a pleadings workshop on the Friday. As usual, the program promises to be of very high quality and an excellent chance for members of the Bar and Bench to gather and share ideas and experiences.

Bar Practice Course

The Bar Association now manages and delivers the Bar Practice Course from the Association’s office.

Throughout the six week Bar Practice Course, held twice a year, the course will be conducted in the Gibbs Room and the newly renovated Mediation Rooms on Level 5 Inns of Court.

The Director, Bar Practice Course, Margaret Voight has as part of the arrangement, joined the staff of the Association.

World Indigenous Law Conference 2014

The Indigenous Lawyers Association of Qld will be hosting the World Indigenous Legal Conference in Brisbane between 24 & 27 June 2014.

The actual program will extend over five days, with select international delegates to attend a trip to a community.

The official opening will be held at the Supreme Court on 24 June 2014. The conference sessions will commence on 25 June ending at lunchtime on 27 June 2014.

The conference will also include a black tie/ traditional dress dinner to be held on 26 June 2014.

Papers have been called for. For more information, contact Joshua Creamer, Barrister-at-Law, who is the President of ILAQ, at jcreamer@qldbar.asn.au

Appointment of President of the Industrial Court

On 1 December 2013, the Honourable Justice Glenn Martin AM took up appointment as President of the Industrial Court of Queensland.

Justice Martin has been a justice of the Supreme Court of Queensland since 31 August 2007. His Honour is well known to members of the Association, having been appointed silk in 1998, having served as President of the Association 2003-2005, President of the Australian Bar Association 2006-2007 and having a very substantial involvement with many aspects of the Association’s activities over many years.

A welcome ceremony for his Honour will be held on Wednesday, 18 December 2013 at 3.30pm in the Main Hearing Room, Level 13 Central Plaza II, 66 Eagle Street, Brisbane.

Valedictory for Fryberg J

A valedictory ceremony was held on 28 November 2013 to mark the retirement of Fryberg J.

His Honour served as a Justice of the Supreme Court since 23 September 1994. His Honour was called to the Bar in 1967 and served as Associate to Sir Victor Windeyer of the High Court. He took silk in 1983.

For a copy of the Chief Justice’s speech from Justice Fryberg’s valedictory — click here.

Appointment of Thomas J

On 17 September 2013, Justice David Thomas was sworn is as a Justice of the Supreme Court. Justice Thomas takes on the role of President of the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal for the next three years, replacing Justice Alan Wilson who has completed a five year term as QCAT’s President.

New Bar Council

At the Annual General Meeting of the Association held on 27 November 2013 the following members were elected:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

President |

|

|

Peter John Davis QC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vice President |

|

|

Shane Lawrence Doyle QC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Council |

|

|

Michael Pascal Amerena |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

James Philip Benjamin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jacoba Brasch |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jeffrey Robert Clarke |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stephen Thomas Courtney |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Geoffrey Warren Diehm QC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Liam Matthew Dollar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peter John Dunning QC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kenneth Charles Fleming QC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joshua Robert Jones |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stephen Joseph Keim S.C. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dean Patrick Morzone QC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ruth Madeline O’Gorman |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mark Oliver Plunkett |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Elizabeth Sybil Wilson QC |

|

New Silks

On 15 November 2013, the following barristers were appointed Queen’s Counsel:

Helen Patricia Bowskill

Thomas Joseph Bradley

Catherine Elena Carew

Peter Alan Hastie

David Robert Kent

Mark David Martin

Timothy Matthews

Damien Peter O’Brien

Adam Michael Pomerenke

Mark Louis Robertson

Soraya Mary Ryan

Rebecca Mary Treston

Manuel Michael Varitimos

Life Members

At the Annual General Meeting of the Association on 27 November 2013, the Hon Justice Patrick Anthony Keane and His Honour Judge Kiernan Damian Dorney QC were each appointed a Life Member of the Association.

Both are well known to members.

Justice Keane graduated from the University of Queensland in 1973 with a Bachelor of Arts and in 1975 with a Bachelor of Laws with first class honours. He was awarded the University Medal in Law and the Walter Harrison Prize, Virgil Power Prize and John Hughes Wilkinson Prize.

His Honour then attended Oxford University and graduated in 1977 with a Bachelor of Civil Laws with first class honours, and was awarded the Vinerian Scholarship and J H C Morris Prize.

Following his return from Oxford, Keane J was called to the Queensland Bar on 15 December 1977, with a successful private practice principally in commercial and constitutional law. He was also a part-time law lecturer at the University of Queensland from 1978 to 1979.

His Honour was appointed Queen’s Counsel on 10 November 1988 after only 11 years at the Bar, and from 1992 until 2005 he held office as Queensland’s Solicitor-General.

During his time at the Bar, Keane J was involved with the work of numerous committees. He was a member of the Supreme Court Library Committee from 1989 to 2005, and Deputy Chairman of the Queensland Law Reform Commission from 1990 to 1992. He was Chairman of the Supreme Court Library Collection Sub-committee from 2006 until 2010. He has assisted the Association’s continuing professional development programme on numerous occasions with presentations and speeches, as well as membership of the Association’s CPD Sub-committee.

In 2001, he was awarded the Centenary Medal by the Commonwealth Government for his distinguished service to the Queensland Bar.

On 21 February 2005, Keane J was sworn in as a Judge of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Queensland.

During his time at the Supreme Court of Queensland, his Honour was a member of the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration from 2006. He chaired the Projects and Research Committee from 2008 until 2010, and was then President of the AIJA from 2010 until September 2011.

Justice Keane was appointed as the Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia on 22 March 2010, and then as a Justice of the High Court of Australia on 5 March 2013.

In 2011, he was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws by University of Queensland.

Judge Dorney QC graduated from the University of Queensland with a Bachelor of Arts in 1967 and from the Australian National University with Bachelor of Laws in 1972.

His Honour was called to the Bar in 1974 and took silk in 1990.

He served as Honorary Secretary of the Association in 1984 and 1985 and as a member of Council from 1989 to 1993. He was Chair for 16 years, from 1993 to 2010 of the Board of Barristers Services Pty Ltd. As Chair of Barristers Services, he made a significant contribution to working with the Council to restructure the Association to make it more efficient and focused on delivering member services and launching Dispute Resolution Services which launched the Bar’s standing as a pre-eminent provider of alternative dispute resolution services.

His Honour also served as a Sessional member of the Commercial & Consumer Tribunal (Q) (2007—2009) and as a Practitioner Member of the Legal Practice Tribunal (Q) (now QCAT) (2004—2010). He was a Member of the Supreme Court Library Committee (1990—2010).

Introduction

In February 1874, the English Court of Appeal handed down its judgment in Barnes v Addy (1874) LR 9 Ch App 244.3 Little could Lord Selborne, who gave the leading judgment, anticipate the significance of his decision, or the controversies surrounding its implications, which still exist even today, well over 100 years later.

Barnes v Addy gave rise to the existence of two separate and distinct causes of action in equity. The first is what is commonly known as a claim for knowing receipt. It arises where a person knowingly receives property in breach of trust. The second is a claim for knowing participation, also referred to as a claim for knowing assistance. It arises where a person has knowingly assisted a trustee to carry out a “dishonest and fraudulent design”. These have become known as the two limbs of Barnes v Addy.

Although Barnes v Addy itself involved an alleged breach of trust, it is now generally considered that such claims also extend to breaches of fiduciary duty. In relation to liability under the second limb of Barnes v Addy, so much has been clear since at least 1975 following the decision in Consul Development v DPC Estates Pty Ltd (1975) 132 CLR 373.4

In relation to first limb liability for knowing receipt, the High Court has not expressly stated that Barnes v Addy liability extends to breaches of fiduciary duty. However, in Farah Constructions v Say-Dee (2007) 230 CLR 895, the High Court stated, at paragraph [113]:

In recent times it has been assumed, but rarely if at all decided, that the first limb applies not only to persons dealing with trustees, but also to persons dealing with at least some other types of fiduciary.

The extension of Barnes v Addy liability to breaches of fiduciary duty is perhaps of most significance, at least in a commercial context, in its application to breaches of fiduciary duties by directors. That is, breach of duty by a director is a sufficient basis on which to ground Barnes v Addy liability, provided the other requirements for a claim are met.

Thus, establishing a breach of trust or breach of fiduciary duty is essential before a claim can be brought. However, where that has happened, the key target of subsequent litigation is often not the trustee or errant director, but rather, third parties who have received assets or who have knowingly assisted in the breach. Most significantly this occurs where the trustee or fiduciary is insolvent or of limited means. In these circumstances, Barnes v Addy provides a potential claim against those third parties who may have “deeper pockets”.

Banks are frequently the targets of Barnes v Addy claims since they are regularly the facilitators or recipients of the movement of funds following a breach of fiduciary duty.6 As the High Court pointed out in Farah Constructions:7

Since the widening of the second limb of Barnes v Addy beyond breaches of express trust, attempts commonly are made in corporate insolvencies to render liable on this footing directors, advisers and bankers of the insolvent company.

This article discusses the deployment of Barnes v Addy by the liquidator of the Bell Group against twenty defendant banks in the recent Western Australian Court of Appeal decision in Bell. Bell is no ordinary case. The trial itself ran for 404 days and resulted in a 2,643 page judgment by Justice Owen. The appeal was then heard over a two month period in 2011 and resulted in a judgment totalling 1,027 pages. Without doubt this makes it one of the largest and longest running commercial trials held in Australia.

Before turning to the facts in Bell, the principles relating to Barnes v Addy, and its modern day interpretation by the High Court in commercial cases, are first re-visited. Three controversies concerning the scope of Barnes v Addy liability are then discussed together with an analysis of how those controversies were addressed in Bell. The article concludes with some practical considerations learnt from Bell when pursuing a Barnes v Addy claim.

Barnes v Addy

Barnes v Addy itself was a case that has little to do with modern day commercial life. It has been described by Lord Walker as a “vignette of family life and family conflict in middle class mid-Victorian England”.8

Facts

The facts were as follows. Two sisters were beneficiaries under their father’s will. One of the sisters was married to Mr Barnes and the other to Mr Addy. The two families did not get on. Mr Addy was the sole trustee of the estate and he held half of the money on trust for his wife and children and the other half for Mr Barnes’ wife and children. Mr Barnes was not happy with this arrangement and wanted to act as trustee for the money left for his wife and children.

Eventually, Mr Addy agreed that Mr Barnes would act as trustee for the money that was to go to Mr Barnes’ wife and children and that he would continue to act as trustee for his own wife and children. Both Mr Barnes and Mr Addy engaged solicitors to bring this into effect. However, shortly after this was achieved, Mr Barnes engaged in a breach of trust. He used the money in his business and became bankrupt.

Mr Barnes’ children sued, amongst others, the two sets of solicitors that prepared the documents appointing their father as trustee. No funds had passed into the solicitors’ hands. The children did not have any contractual relationship with the solicitors. Issues of negligence simply did not arise because Donoghue v Stevenson9 would not be decided for another 50 years. So, what was the Court to do? In the Court of Appeal in Chancery, Lord Selborne said this:10

Strangers are not to be made constructive trustees merely because they act as the agents of trustees in transactions within their legal powers, transactions, perhaps of which a Court of Equity may disapprove, unless:

Strangers are not to be made constructive trustees merely because they act as the agents of trustees in transactions within their legal powers, transactions, perhaps of which a Court of Equity may disapprove, unless:

(a) those agents receive and become chargeable with some part of the trust property, [knowing receipt]

(b) or unless they assist with knowledge in a dishonest and fraudulent design on the part of the trustees. [knowing assistance]

[words in brackets added]

Lord Selborne did not split out the two limbs into (a) and (b) above, but the words in (a) are now commonly referred to as a claim in knowing receipt, the first limb of Barnes v Addy, and the words in (b) are referred to as a claim in knowing assistance or knowing participation, the second limb of Barnes v Addy. Under both limbs, the Courts use knowledge as the “gatekeeper” in controlling liability. That is, knowledge of the breach is essential to ground liability.

Ultimately, the solicitors in Barnes v Addy were found not liable as they did not have knowledge of the breach of trust.

Modern commercial cases on Barnes v Addy

Most modern commercial cases are not concerned with breaches of express trusts, but rather, breaches of fiduciary duty by company directors or other persons standing in a fiduciary relationship. The High Court has only had two opportunities to consider Barnes v Addy liability. Both concerned breaches of fiduciary duty in commercial contexts. The first was its 1975 decision in Consul Development and the second was its 2007 decision in Farah Constructions.

Consul Development

The facts in Consul Development are well known. In essence, a solicitor, in addition to his legal practice, also carried on a property development business through his company, DPC Estates. Mr Grey was a director and manager of DPC Estates. An articled clerk who worked for the solicitor also engaged in a separate property development business through a family company, called Consul Development. Mr Grey diverted opportunities from DPC Estates to Consul Development in return for a share of its profits.

Thus, Mr Grey was alleged to have breached the fiduciary duties he owed to DPC Estates by diverting business opportunities to Consul Development. DPC Estates sued Mr Grey and Consul Development. The cause of action against Consul Development is the relevant claim for current purposes. It was a claim for knowing participation under the second limb of Barnes v Addy. DPC Estates claimed that the properties purchased by Consul Development were held on constructive trust for it.

The critical issue before the High Court was whether constructive knowledge was sufficient to attract liability under the second limb of Barnes v Addy for knowing participation. Ultimately, the High Court rejected the claim. This was because Consul Development did not have the requisite knowledge of Mr Grey’s breach. However, the Court did not speak with one voice on whether constructive knowledge was sufficient to establish liability.11

Farah Constructions

It took over three decades for that controversy to be resolved when the High Court heard Farah Constructions, on appeal from the NSW Court of Appeal.

Facts

The facts in Farah Constructions were complicated. In essence, Farah and Say-Dee were involved in a joint venture to develop land in Sydney. However, the local council refused development approval. Farah’s director subsequently became aware that the Council was more likely to approve the development if the neighbouring properties were purchased.

In light of this, the director purchased those properties in the name of a company he controlled and in the name of his wife and daughters. The other joint venturer, Say-Dee, sued Farah and its related entities for the resulting gains, deploying causes of action for knowing receipt and knowing participation. Say-Dee argued that the properties were held on constructive trust because the potential to develop the site was confidential information. By not disclosing that information, Say-Dee alleged that Farah had breached its fiduciary duties.

Ultimately, the High Court, in a joint judgment of Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Callinan, Heydon and Crennan JJ, held that there was no breach of fiduciary duty. This was because proper disclosure had been made to Say-Dee of the potential benefits of purchasing the neighbouring properties. Given that there was no breach, that disposed of the case. However, the Court went on to discuss the other aspects of Say-Dee’s claims.

In relation to the claim under the first limb of Barnes v Addy, the Court found that the knowing receipt claim would have failed in any event. Their Honours said it was essential in a knowing receipt claim for the defendant to receive property. All the defendant had received here was information. Information is not property. In any event, that information had not been transferred to the wife and daughters. Thus, those defendants had not received any property belonging to the plaintiffs. Therefore, they could not be liable for knowing receipt.

The High Court also considered the scope of liability for knowing participation under the second limb of Barnes v Addy. The High Court resolved the controversy that had existed since Consul Development in relation to the necessary state of knowledge for second limb liability. The Court found that12 “Baden 4” knowledge is sufficient to attract liability.

By Baden 4 knowledge, the Court was referring to Mr Justice Peter Gibson’s decision in Baden v Societe Generale.13 In that case, his Honour set out 5 categories of knowledge:

(a) Actual knowledge;

(b) Wilfully shutting one’s eyes to the obvious;

(c) Wilfully and recklessly failing to make such enquiries as an honest and reasonable man would make;

(d) Knowledge of circumstances which would indicate the facts to an honest and reasonable man; and

(e) Knowledge of circumstances which would put an honest and reasonable man on inquiry.

The categories of knowledge are set out in descending order, with the highest state of knowledge in the first category and the lowest state of knowledge in the last. Thus, knowledge in any of the first 4 of those categories is sufficient in a claim under the second limb for knowing participation. Their Honours put it like this:14

The result is that Consul supports the proposition that circumstances falling within any of the first four categories of Baden are sufficient to answer the requirement of knowledge in the second limb of Barnes v Addy, but does not travel fully into the field of constructive notice by accepting the fifth category. In this way, there is accommodated, through acceptance of the fourth category, the proposition that the morally obtuse cannot escape by failure to recognise an impropriety that would have been apparent to an ordinary person applying the standards of such persons.

However, while it is easy to state what each of the categories are, fitting a set of facts into one category rather than another can be very difficult. Perhaps for this reason, the Baden scale of knowledge has its critics. Writing extra-judicially, Justice Finn has described it as “technical to the point of the artificial and the arcane.”15 Nonetheless, it is important because it sets the boundaries of liability.

In Farah Constructions, the High Court did not resolve whether the same or a different level of knowledge applies in a claim under the first limb of Barnes v Addy for knowing receipt. Ultimately, their Honours found that even if there had been a failure by Farah to disclose adequately the information to Say-Dee, this did not amount to a dishonest and fraudulent design for the purposes of second limb liability. Further, the wife and daughters did not have notice of any breach so as to render them liable. Thus, Farah was wholly successful in its appeal.

The Bell litigation

The above principles, providing for equitable relief against third parties following a breach of fiduciary duty by a director, were deployed “writ-large” in Bell.

The basic facts in Bell

The Bell Group Limited was a publicly listed company controlled by Robert Holmes a Court. It was the ultimate holding company of a large corporate group (the Bell Group).

The Bell Group owned two principal assets. The first was the “Western Australian” newspaper and the second was shares in Bell Resources Limited.

The financing entity within the Group, Bell Group Finance Pty Ltd (BGF), had borrowed approximately $260 million in total from 20 Banks. This included separate facilities with 6 Australian banks, as well as a facility it had from a syndicate of 14 overseas banks (the Lloyds Syndicate Banks). The Australian banks included Westpac, NAB and the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

All of the bank lending was unsecured. The facilities were entered into on a negative pledge basis, whereby the Banks received the benefit of a contractual covenant that no security would be granted without their consent.

In 1988, entities associated with Alan Bond’s Bond Corporations Holdings Limited took over control of The Bell Group Limited. Later in 1988 and 1989 there was public speculation about the financial health of the Bell Group. It was rumoured that the whole group may collapse. As unsecured lenders, the Banks would have ranked pari passu with other creditors in a liquidation scenario. Thus, the Banks entered into negotiations with the Bell Group to take security over all of the group’s assets.

Security documents were entered into in January 1990 in which security was taken over all of the assets in the Bell Group, including its 2 principal assets – Western Australian newspapers and the shares in Bell Resources Limited. In return, the Australian Banks agreed to extend their facilities from being payable on demand to being payable fourteen months later in May 1991. The Lloyds Syndicate Banks agreed to extend their facilities by 11 days.

The following year, in 1991, the Banks appointed receivers who sold all of the Bell Group’s assets to repay the Banks. The Banks received the full amount of their loans, together with interest, a total of $283 million. Subsequently, a liquidator was appointed to the Bell Group companies. There was no money available to pay unsecured creditors.

How the liquidator mounted a claim against the Banks

It was in these circumstances that the liquidator instituted proceedings to set aside the Banks’ securities and “claw back” the money paid to them.16 The real problem for the liquidator was that the securities were granted about 18 months prior to the liquidation. Thus, the liquidator was time barred from bringing an unfair preference claim. A different cause of action had to be developed.

The primary causes of action deployed were claims in knowing receipt and knowing participation under the first and second limbs of Barnes v Addy. In essence, the liquidator’s argument ran as follows:

(a) First, that the directors of the Bell Group breached their duties in granting the securities because they knew the companies were insolvent at the time.

(b) Three breaches were alleged: breach of the duty to act bona fide in the best interests of the company; breach of the duty to exercise powers for a proper purpose; and breach of the duty to avoid conflicts of interest.

(c) The critical point in establishing the directors’ breaches of duty was this. The liquidator said that there was simply no benefit for any of the Bell Group companies in granting the securities. They did not get the benefit of any new advances by the Banks, nor did they get the benefit of more favourable terms on their loans.

(d) The directors also knew that the effect of granting the securities was that all of the Bell Group’s assets were made available to the Banks for repayment of their debts in priority to the claims of other creditors.

(e) Second, that the Banks knew that the directors were breaching their duties in granting the securities and actively participated in that breach.

(f) Third, when the Banks realised on their securities, they thereby received “tainted money”. That is, the Banks received that money in circumstances where they knew that their securities had been granted pursuant to a breach of duty by the directors. Therefore, that money should be disgorged.

By way of defence17, the Banks said the companies were not insolvent and even if they were, they had no knowledge of the insolvency. The Banks also argued that the transactions gave the Bell Group “breathing space” and time to consider an orderly workout. The Banks said that without the securities, they would have enforced on their debts immediately. Thus, the granting of security was an essential “first step” in agreeing upon a workout and restoring the group’s financial health.

At first instance, the case came before Justice Owen in the Western Australia Supreme Court. His Honour accepted the liquidator’s case and ordered that all of the Banks’ securities be overturned and that they pay almost $1.6 billion to the liquidator.

The Banks then appealed to the WA Court of Appeal. Interestingly, a specially constituted Court was convened for the appeal constituting solely of judges from outside the Western Australian Court of Appeal or Supreme Court. Thus, the appeal Court consisted of three retired Federal Court Judges, Justices Drummond, Carr and Lee. This was said by the WA Attorney-General to be necessary “so as to not affect the discharge of the normal work of the Supreme Court.”18

By a 2-1 majority (Justice Carr dissenting), their Honours upheld Justice Owen’s findings. In short, the Court ordered the Banks to return the $283 million they received upon enforcement of their securities, together with compound interest, at monthly rests on that amount. At first instance, Justice Owen had ordered compound interest on this amount from 1991 to 2009. The effect was to increase the total award from $280 million to approximately $1.6 billion.

Justice Carr, in the minority, rejected the Barnes v Addy claims on the basis that none of the directors had breached their fiduciary duties.19 His Honour was also wary of extending equitable remedies into a field where the insolvency regime already provided protection:20

The insolvency regime to which I have just referred provides adequate protection for the unfavoured creditors. There is no need, in my view, to stretch Barnes v Addy to provide them with a remedy. …

Where, as in this case, the directors were not dishonest but, with the benefit of hindsight, are judged to have made a commercial mistake, in my opinion the insolvency laws should be deployed to do their work untroubled by 19th century equitable principles derived from the law of trustees.

Nonetheless, by a 2 to 1 majority, the liquidator succeeded in upholding his knowing receipt claim.

One of the issues in the appeal was the appropriate interest rate to use. The liquidator contended that the interest rate should be increased by 2%. Justices Drummond and Lee agreed. The effect was to increase the total award from $1.6 billion to somewhere between $2 and $3 billion.

The liquidator also ran an alternative argument in the appeal seeking an account of profits. That is, the liquidator argued that he should be awarded the profits that the Banks made with $283 million between 1991 and 2009. Thus, if, for example, the Banks made a 10% return year on year, that rate of return would be applied to the $283 million over that period.

However, the Court of Appeal refused to award an account of profits. Their Honours found that it would be an improper use of the Court’s resources for the parties to engage in another substantial hearing to determine the size of the profits earned by 20 banks over a period of almost two decades.

Three points of controversy

Bell is significant in that addresses a number of the “myriad of problems”21 concerning the scope of Barnes v Addy liability. In particular, it addresses at least three controversies that still exist following the High Court’s decision in Farah Constructions. Those controversies are:

(a) first, what state of knowledge is sufficient for a claim in knowing receipt under the first limb of Barnes v Addy?

(b) second, what is a “dishonest and fraudulent design” for the purposes of the second limb?

(c) third, what is a fiduciary duty (a question which is relevant to liability under both limbs)?

Each of these controversies is addressed in turn below.

First controversy: what state of knowledge is sufficient for a claim in knowing receipt?

The first controversy relates to the state of knowledge that is necessary to attract liability for knowing receipt under the first limb of Barnes v Addy. In Bell, Justice Drummond referred to other authorities in which first limb liability had been extended to breaches of fiduciary duty and had no difficulty doing so himself.22

His Honour noted that the High Court in Farah Constructions did not settle the law with respect to the knowledge requirement under the first limb.23 The High Court simply said in that case that “persons who receive trust property become chargeable if it is established that they received it with notice of the trust”.24

It has been said that a less exacting degree of knowledge of the breach applies under the first limb.25 This perhaps stems from the different natures of the causes of action. Under a claim for knowing receipt, the defendant must beneficially receive property. Thus, in knowing receipt cases the defendant has received a benefit. By comparison, under a claim for knowing participation, it is not necessary that property be received, but rather, the defendant must knowingly participate in a dishonest and fraudulent design. Thus, in those cases, the defendant may not have received a benefit and may have to pay any equitable compensation out of its own resources.

Perhaps the best explanation of the different roles said to be performed by the two limbs was Millett J’s analysis (as he then was) in Agip (Africa) Ltd v Jackson [1990] Ch 26526. In that case, his Honour set out his view as to why a different test of knowledge should apply:27

The basis of liability in the two types of cases is quite different; there is no reason why the degree of knowledge required should be the same, and good reason why it should not. Tracing claims and cases of “knowing receipt” are both concerned with rights of priority in relation to property taken by a legal owner for his own benefit; cases of “knowing assistance” are concerned with the furtherance of fraud.

In Bell, Justice Drummond relied upon the recent decision of the Full Federal Court in Grimaldi v Chameleon Mining NL (No 2) (2012) 200 FCR 29628 in which the Court did not follow Millett J’s reasoning and found that the same test of knowledge should apply under both the first and second limb of Barnes v Addy. His Honour quoted from the Full Court’s decision as to why the knowledge requirement is the same:29

… We do not consider that a property protection rationale for recipient liability … of itself provides a sufficient justification for imposing a personal liability to account. That liability arises as a matter of conscience not of property. As with assistance liability, recipient liability should be seen as fault based and as making the same knowledge / notice demands as in assistance cases. We need not pursue this particular matter further because the weight of authority in this country appears now to draw no distinction between the two types of liability in this respect.

[emphasis in original]

Thus, following the Full Court in Grimaldi, Justice Drummond held that Baden level 4 knowledge will suffice for a knowing receipt claim.30 Justice Lee agreed with Justice Drummond in this regard.31

Second controversy: what is a dishonest and fraudulent design?

The second controversy addressed by the appeal Court in Bell relates what amounts to a “dishonest and fraudulent design” for the purposes of a knowing participation claim under the second limb of Barnes v Addy. Establishing a dishonest and fraudulent design is essential in bringing such a claim.

Of course, the dishonest and fraudulent design is necessarily one carried out by the trustee or fiduciary. It is not necessary that the defendant was dishonest. The defendant has to have knowledge of, and participate in, the dishonest and fraudulent design. But what is meant by this phrase? On its face it sounds quite sinister. However, it arises in the context of an equitable cause of action – equity traditionally taking a wider view of what amounts to fraud than the common law. The nub of the issue seems to be this. A breach of fiduciary duty can be sufficient to amount to a dishonest and fraudulent design. But how serious must the breach be to amount to a “dishonest and fraudulent design”?

In Bell, the Banks argued a dishonest and fraudulent design required proof of “conscious dishonesty” by the directors. That is, the Banks contended that they could only be found liable if the directors subjectively knew they were breaching their duties. The Banks submitted that in the absence of such a finding, it was not possible to find them liable under the second limb of Barnes v Addy for knowing participation.

At first instance, Justice Owen accepted that submission. His Honour considered that to establish a dishonest and fraudulent design, it was necessary to plead and prove subjective dishonesty. That finding was challenged by the liquidator on appeal.

The High Court had addressed this issue in Farah Constructions, although only briefly.32 Drummond J stated that the discussion on this point in Farah was not entirely clear to him, but his Honour drew three principles from that case:33

(a) First, not every breach of trust or breach of fiduciary duty will amount to a “dishonest and fraudulent design”;

(b) Second, it is not necessary to show conscious dishonesty on the part of the fiduciary. It is sufficient that the breach would be dishonest according to equitable principles (ie. objective dishonesty); and

(c) Third, the breach must be more than a trivial breach. A breach of director’s duty will be more than trivial if it is one that would not be excused under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), s 1318 or the equivalent section of the Trusts Act in each of the States and Territories.34 Under s 1318, a Court can excuse a breach of director’s duty if the director acted honestly, reasonably and ought fairly to be excused.

Thus, if this reasoning takes hold, the test is an objective test. There is no need to establish that the trustee or fiduciary subjectively knew he was breaching his duties.

Further, if Justice Drummond’s reasoning finds support elsewhere, the authorities on the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), s 1318 may be relied upon in equity suits as guidance on whether a breach of director’s duty is sufficiently serious to amount to a dishonest and fraudulent design.35

In summary, although the phrase “dishonest and fraudulent design” may sound sinister, it seems that the “bar may be set pretty low”.36

Third controversy: What is a fiduciary duty?

The third controversy addressed in Bell relates to which directors’ duties are fiduciary in nature. Breach of a fiduciary duty is essential when bringing a Barnes v Addy claim. Without such a breach, there simply is no cause of action.

In this context, it is trite law that directors stand in a fiduciary relationship with their company. However, simply because directors are fiduciaries does not mean that every duty owed by a director is a fiduciary duty. Thus, in the context of Barnes v Addy liability, a real question arises as to which of the duties owed by a director are fiduciary and which are not.

A basic list of directors’ duties may read as follows:

(a) Duty to act with reasonable care and diligence.

(b) Duty to act bona fide in the best interests of the company as a whole.

(c) Duty to act for proper purposes.

(d) Avoidance of conflicts of interest.

(e) Avoidance of unauthorised profits.

The first three of these duties are expressed in the positive – a positive duty to do something, whereas the last two are expressed in the negative – things that a fiduciary must avoid.

In Bell, the Banks argued that the only duties that are fiduciary are the proscriptive duties, namely, the duties governing what a director cannot do. If that is correct, it would mean that the only fiduciary duties are the duty to avoid conflicts of interest and the duty to avoid making unauthorised profits.

Critical to the Banks’ argument was the following statement by Justices Gaudron and McHugh in Breen v Williams (1996) 186 CLR 71 at 113:

In this country, fiduciary obligations arise because a person has come under an obligation to act in another’s interests. As a result, equity imposes on the fiduciary proscriptive obligations – not to obtain any unauthorised benefit from the relationship and not to be in a position of conflict. If these obligations are breached, the fiduciary must account for any profits and make good any losses arising from the breach. But the law of this country does not otherwise impose any positive legal duties on the fiduciary to act in the interests of the person to whom the duty is owed.

That statement was approved in Pilmer v Duke Group Ltd (in liq) (2001) 207 CLR 165 at 198 by Justices McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan.

The two critical duties in question in Bell were:

(a) The duty to act bona fide in the best interests of the company as a whole; and

(b) The duty to act for proper purposes.

Neither of these are proscriptive duties: both require a director to take positive acts. Thus, the Court had to determine whether these duties are fiduciary in nature. In resolving this question an element of policy may be involved. As Justice Carr stated:37

If, as must be the case, some of a company director’s powers when exercised do not involve assuming a fiduciary duty but others do, how is the line drawn between the two types of powers? It may be by exercising what might be described as judicial policy either to intervene with proprietary equitable relief (or other equitable relief) or not to do so.

Justice Drummond conducted an analysis of the authorities and found that the duties pleaded by the liquidator were fiduciary in nature. His Honour concluded:38

Neither decision in Breen or Pilmer considered the position of directors who undoubtedly stand in a fiduciary relationship with their company and who have long been subject to duties to act bona fide in the interests of the company and to exercise their powers for proper purposes, both of which have long been described as fiduciary obligations. If the fiduciary obligations of directors to their company are limited to the two proscriptive ones … an extensive revision of the law governing directors’ duties must have taken place without any examination of that particular issue at the intermediate or final appellate level.

Justice Lee agreed with Drummond J on this finding.39 Although Justice Carr was in the minority, his Honour came to the same conclusion.40

Some practical considerations

Bell also provides important learnings on the practical considerations of deploying a Barnes v Addy cause of action. There are at least three worthy of mention.

The first relates to the proper parties to the proceedings. In particular, it is not necessary to join the errant fiduciary or trustee as a party. Thus, there is no need to join the director who is alleged to have breached his fiduciary duties.41 The directors were not parties at trial in the Bell litigation.

The second relates to proving dishonesty against the trustee or director. Bell is authority for the proposition that there is no need to establish conscious dishonesty (see above). It is sufficient if a person in the director’s shoes should have known he was breaching his fiduciary duties. Thus, establishing what facts were known by the director and asking the Court to draw inferences about the director’s state of knowledge from those facts will be critical.

The third practical consideration is a pleading point and relates to establishing that the trustee or director engaged in a “dishonest and fraudulent design”. If Justice Drummond’s analysis (discussed above) finds support elsewhere, to prove this it may be necessary to establish whether or not the director was acting honestly, reasonably and should be excused. A question then arises as to who bears the onus in establishing this allegation. Is it an element of a cause of action under the second limb of Barnes v Addy? If so, it seems that it would be for the plaintiff to plead and prove that the director was not acting honestly or reasonably and should not be excused.

Conclusion

Barnes v Addy remains a potential source of liability for directors, advisers and bankers. In particular, where a breach of trust or fiduciary duty has occurred, it provides a means of pursuing such persons where they have received property or participated in the breach. However, despite dating from 1874, with numerous decisions in the intervening years, the precise limits of liability remains uncertain.

In Bell, the WA Court of Appeal had to grapple with at least three of those uncertainties, first what state of knowledge is sufficient for a claim in knowing receipt; second, what amounts to a dishonest and fraudulent design; and third, which directors’ duties are fiduciary in nature.

The Banks have now been granted special leave to appeal to the High Court.42 Amongst the issues to be ventilated on appeal are whether the fiduciary duties of company directors extend to prescriptive duties and if so, which ones; whether the first limb of Barnes v Addy extends to breaches of fiduciary duty and whether the Court of Appeal correctly imposed the appropriate rate of interest when awarding compound interest. Needless to say, it is hoped that the High Court’s decision on these points will clarify some of the difficulties posed in identifying the limits of Barnes v Addy liability.43 For now, the Court of Appeal’s decision in Bell provides helpful guidance on how to deal with some of these “myriad” difficulties.

Dan Butler

15 August 2013

Footnotes

- A version of this paper was published in the August 2013 edition of the Company and Securities Law Journal: see Equitable Remedies for participation in a breach of directors’ fiduciary duties: the mega litigation in Bell v Westpac; Butler; (2013) 31 C&SLJ 307. The paper is being re-published in Hearsay with the kind permission of Thomson Reuters, who hold the copyright.

- Hereafter referred to as Bell.

- Hereafter referred to as Barnes v Addy.

- Hereafter referred to as Consul Development.

- Hereafter referred to as Farah Constructions.

- See, for example, Ninety Five Pty Ltd (in liq) v Banque Nationale de Paris [1988] WAR 132; Equiticorp Finance Ltd (in liq) v Bank of New Zealand (1993) 32 NSWLR 50; 11 ACSR 642; Koorootang Nominees Pty Ltd v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [1998] 3 VR 16; Baden v Societe Generale Pour Favoriser le Development du Commerce et de l’Industrie en France SA [1992] 4 All ER 161; [1993] 1 WLR 509.

- Farah Constructions, n 5, at [179].

- R Walker, “Dishonesty and Unconscionable Conduct in Commercial Life – Some Reflections on Accessory Liability and Knowing Receipt,” (2005), Number 2, Sydney Law Review, 187 at 188.

- Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562. Indeed, difficult questions surrounding the existence and scope of a duty of care outside the context of injury to a person or a person’s property would only be confronted in the fullness of time. See, for example, Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Hellar & Partners Ltd [1964] AC 465 and Hawkins v Clayton (1988) 164 CLR 539. Of course, the appellate Courts still deal with difficult duty questions even today.

- Barnes v Addy, n 3, at 251 – 252.

- See the High Court’s analysis in Farah Constructions, n 5, at [176] of the earlier discussion of the knowledge requirement in Consul Development, n 4.

- Farah Constructions, n 5, at [171] – [178].

- Baden v Societe Generale [1993] 1 WLR 509 at 575 – 576.

- Farah Constructions, n 5, at [177].

- D Waters (ed), “Equity, Fiduciaries and Trusts” (1993) at 195 – 196.

- One significant aspect of the case which need not be discussed here relates to $550 million of convertible subordinated bonds issued by entities within the Bell Group. The Banks contended that monies on-lent within the Bell Group from the proceeds of these bonds were also subordinated. Thus, as part of their defence, the Banks contended that granting the securities did not prefer them to other creditors because the only other debts were the on-loans from these bonds, which were subordinated.

- Bell, n 2, at [2704].

- D Guest, “Retired Federal Court Judges to Hear Bell Group Appeal”, (The Australian Newspaper), 6 December 2010.

- Bell, n 2, at [2985], [3052] and [3062].

- Bell, n 2, at [3062] – [3063].

- T Boyle, ‘‘Never Say-Dee: The ongoing relevance of the ‘first limb’ of Barnes v Addy in modern Australian law,” (2011) 5 Journal of Equity 123 at 124.

- Bell, n 2, at [2136].

- Bell, n 2, at [2127].

- Farah Constructions, n 5, at [112].

- See, for example, Ninety Five Pty Ltd (in liq) v Banque Nationale de Paris [1988] WAR 132 at 176.

- Hereafter referred to as Agip Africa.

- Agip Africa, n 26, at 292 – 293.

- Hereafter referred to as Grimaldi.

- Bell, above, n 2, at [2129]; Grimaldi above, n 28, at [267].

- Bell, n 2, at [2130].

- Bell, n 2, at [1099].

- Farah Constructions, n 5, at [179] – [184].

- Bell, n 2, at [2112].

- In Western Australia, the relevant provision is contained in the Trustees Act 1962 (WA), s 75.

- Bell, n 2, at [2113].

- Bell, n 2, at [2125].

- Bell, n 2, at [2717].

- Bell, n 2, at [1962].

- Bell, n 2, at [1099].

- Bell, n 2, at [2733]. In this context, Justice Finn’s judgment in Grimaldi, n 28, is also instructive. See, for example, paragraphs [174] and [178].

- Bell, n 2, at [2125].

- Westpac Banking Corporation & Ors v The Bell Group Ltd & Ors [2013] HCA Trans 49 (15 March 2013).

- After this paper was finalised, the Bell litigation was settled. Thus, determination of these important points by the High Court will have to await another occasion.

Justice system failing to deal with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

10 December 2013

People suffering from Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, also known as FasD, often have reduced impulse control and are simply too trusting. Others are violent and so cognitively impaired that they are unfit to stand trial. But when defendants with FASD come to the attention of the law, they often encounter a system that seems fundamentally unable to cope with the range of challenging behaviours that their disorder brings. As a result, many end up behind bars, in some cases for just minor offenses.

South African judge speaks out on life with HIV

3 December 2013

While millions of people have died from HIV/AIDS throughout Africa there still remains silence around the disease.

One man who has done an enormous amount to break down the stigma is Edwin Cameron, a judge of South Africa’s highest court. Justice Cameron is the only office holder in the African continent to acknowledge that he is living with HIV.

His career has been one that has tested the boundaries of activism and judicial duties and has thrown him into conflict with his country’s most powerful political forces.

This program was first broadcast on 7th May 2013

Digital wills

26 November 2013

If you tap out a will on your smart phone, will it be recognised under law? A recent decision of the Queensland Supreme Court on one such case adds clarity to an area of the law which is seeing an increased use of alternatives to paper-based testaments.

NZ program strives to give peace to sexual assault survivors

26 November 2013

An innovative program in New Zealand, called Project Restore, is providing a new avenue for victims of sexual assault to confront perpetrators and deal with the devastating impact of offending behaviour, and the associated anxiety that can trail survivors for years.

The ABA Journal website can be accessed at http://www.abajournal.com/

A selection of recent items are listed below and members are invited to explore the vast array of articles that are continually posted.

Arms Control Law

Posts analyze and discuss legal issues relevant to arms control, including actions of the International Atomic Energy Agency and the dispute between the West and Iran over Iran’s nuclear program.

View blog

Legally Weird

Bloggers comment on the legal angles of true stories in the news that are stranger than fiction.

View blog

Medical Futility Blog

Posts take note of life-support disputes in the news, discuss scholarship from critical care ethicists and explore the legality and ethics of patients’ different end-of-life options.

View blog

Chasing Truth. Catching Hell.

The aim of the blog is to help readers have a more informed opinion about the criminal justice system and the effects on those who come in contact with it.

View blog

2013 has been a busy year for the Supreme Court Library, as we’ve worked to enhance services to all of our customers — including members of the Queensland Bar. It’s also been a year of significant changes, which have included:

- establishing the library in its attractive and functional new premises within the Queen Elizabeth II Courts of Law in the Brisbane CBD

- taking over provision of the Queensland Sentencing Information Service (QSIS)

- farewelling our long serving Librarian Aladin Rahemtula OAM in August and welcoming our new Librarian (me) in September.

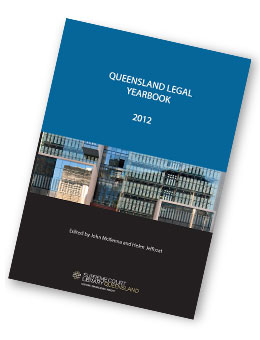

![David-Bratchford-cropped[2].jpg](https://www.hearsay.org.au/carbon/assets/2013/03/David-Bratchford-cropped2.jpg) Each year the Supreme Court Library publishes the Queensland Legal Yearbook as a consolidated record of Queensland’s past legal year. The latest edition (2012) is dedicated to the opening of the Queen Elizabeth II Courts of Law. It includes:

Each year the Supreme Court Library publishes the Queensland Legal Yearbook as a consolidated record of Queensland’s past legal year. The latest edition (2012) is dedicated to the opening of the Queen Elizabeth II Courts of Law. It includes:

- essays by the project’s lead architect and eminent members of the judiciary and legal profession on aspects of the design of the building and the relocation of the courts to their new premises

- records of court ceremonies, including valedictories and swearings-in, as well as legal speeches and lectures (including the 2012 Supreme Court Oration) held throughout the year

- tributes to judges who passed away during 2012

- legal personalia, including profiles of judges and magistrates and details of appointments and admissions

- the Queensland Legal Year in review – a timeline of key legal events for the year

- legal statistics relating to the judiciary and legal profession, including key performance

indicators of the Queensland Courts

indicators of the Queensland Courts

- reviews of significant legal publications released in 2012

To celebrate the past year, your library will be providing free copies of the latest Yearbook to members of the legal profession. To collect your free copy, visit us at the library in Brisbane during court opening hours, attend a lecture or other event at the library, or contact us at librarian@sclqld.org.au to register your interest.

We look forward to assisting you with your legal information needs in 2014. If you are not already a member of the library, you can register for free on our website, under For Legal Profession Ç Patron Registration Form.

You’re always welcome to visit us in person, telephone us on 07 3247 4393, email us at the above address, or visit our website.

Supreme Court Library

Level 12

Queen Elizabeth II Courts of Law

Brisbane, Queensland

www.sclqld.org.au

1. This paper is the first of a series of studies to be undertaken by the Queensland Supreme Court Library of an extensive collection of counsels’ opinions held by the Queensland firm of Feez Ruthning. I would like to thank Peter Allen and the other former partners of Feez Ruthning (now Allens Linklaters) for their foresight in preserving this unique record of Australian legal history and for their generosity in making it available to the Queensland Supreme Court Library for research purposes. I would also like to thank Helen Jeffcoat, Yvette Simmonson, Courtney Coyne and the staff of the Queensland Supreme Court Library for their ongoing work in preserving, digitising, transcribing, analysing and investigating the accessible contents of this material. I am also very grateful to Mr Greg Cooper, Crown Solicitor, for allowing the Supreme Court Library confidential access, for the purposes of this study, to the collection of Griffith opinions which are held by the State, but which remain subject to legal professional privilege.

2. The most extensive account of Griffith’s life, written from an historian’s perspective, remains Roger Joyce’s Samuel Walker Griffith (UQP, 1984). See also R Joyce “Sir Samuel Walker Griffith (1845-1920)” in Australian Dictionary of Biography Volume 9 (MUP, 1983). For a personal memoir of Griffith and his legal achievements, written by a distinguished lawyer who was once one of Griffith’s associates, see A.D.Graham The Life of Sir Samuel Griffith (Powells & Pughs, 1939). For assessments of Griffith’s judicial work, see Sir H.T. Gibbs “Samuel Walker Griffith” in T.Blackshield, M.Coper & G.Williams (Eds) Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (OUP, 2001); Sir H.T. Gibbs and P.A.Keane “Sir Samuel Griffith” in M.White and A.Rahemtula (Eds) Queensland Judges on the High Court (SCL, 2003); and M. White and A. Rahemtula (Eds) Sir Samuel Griffith: The Law and the Constitution (LBC, 2002).

3. Lengthy tributes appeared in all major Australian newspapers, including the Brisbane Courier, 10 August 1920 at 7; Sydney Morning Herald, 10 August 1920 at 6 and the West Australian, 10 August 1920, at 6.

4. Brisbane Courier, 10 August 1920, at 7.

5. Knox CJ, Ceremonial sitting of the High Court, 10 August 1920, reported in Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 1920 at 12.

6. Macalister was one of the leading legal and political figures in early Queensland. After playing an active role in the movement for Queensland’s separation, he was elected to Queensland’s first Legislative Assembly. At the commencement of Griffith’s articles, Macalister was dividing his time between practice as a solicitor and serving in Herbert’s government as Secretary for Land and Works. By the end of Griffith’s articles, Macalister had succeeded Herbert and served two short terms as Premier of Queensland (1866, 1866-67). When Griffith commenced practice at the Bar, Macalister’s firm was one of his early supporters. See Paul D Wilson “Arthur Macalister (1818-1883)” in Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol 5 (MUP, 1874).

7. Griffith was admitted to the Bar on 14 October 1867, at a sitting of the Full Court comprising Cockle CJ and Lutwyche J. His admission was moved by Charles Lilley QC. See Brisbane Courier, 15 October 1867, at 2. At the time, the Queensland Bar comprised fewer than 20 practising members (including only two silks): see Pugh’s Almanac 1868 at 75.

8. The Town Hall, which was opened in 1864, was designed to include professional offices. An early photograph of the façade of the Town Hall (which was demolished in 1937) can be seen in JD McKenna Supreme Court of Queensland: A Concise History (UQP, 2012) at 61 (“Concise History”). Macalister was one of the solicitors who kept an office in the building: see, eg, Brisbane Courier, 7 October 1864, at 1. This seems to have been the office where Griffith was based during the latter period of his articles. When Griffith commenced practice at the Bar, he began by sharing chambers in the Town Hall with George Paul (later a Judge of the District Court). All Griffith’s early opinions are signed “Town Hall Chambers”: Concise History, at 68.

9. Plans and early photographs of the Convict Barracks can be seen in the Concise History at 29, 42 and 44.

10. Roll of Her Majesty’s Counsel, Concise History at 47.

11. This appears from the Griffith Opinions which, from November 1886, are signed “Lutwyche Chambers”.

12. Lutwyche Chambers, which opened in 1885, stood at 11/13 Adelaide Street. It was a two-storied building which accommodated, on the ground floor, the solicitors’ firm of Macpherson, Miskin & Feez (later Feez Ruthning & Baynes) and three barristers’ chambers, with chambers for five more barristers on the first floor. See Pugh’s Almanac 1915 at 479. A photograph showing Lutwyche Chambers in the 1950s appears in the Concise History at 159 (far right),

13. Joyce, op cit, at 90.

14. AB Piddington Worshipful Masters (A&R, 1929) at 234.

15. See Pugh’s Almanac 1893, “Department of Justice”, at 128

16. In his first two years in Parliament, Griffith drafted and introduced the Telegraphic Messages Act 1872 (Qld) and the Equity Procedure Act 1873 (Qld): Joyce, op cit, at 31-32.

17. Griffith, as Attorney-General, was responsible for the introduction to Queensland of the most significant reforms in court procedures of this era: Judicature Act 1876 (Qld).

18. Joyce, op cit, at 150.

19. For example, the legalisation of trade unions (Trade Unions Act 1886 (Qld)).

20. Joyce, op cit, at 90.

21. The various drafts which were produced, in quick succession, by Griffith are collected in J.Williams The Australian Constitution: A Documentary History (MUP, 2005).

22. A.Deakin The Federal Story (MUP, 1963)at 52.

23. Chief Justice’s Salary Act 1892 (Qld).

24. Chief Justice’s Salary Act 1902 (Qld).

25. BH McPherson The Supreme Court of Queensland (Butterworths, 1989) at 191.

26. Sir H.T. Gibbs “Sir Samuel Griffith” in M.White and A.Rahemtula (Eds) Queensland Judges on the High Court (SCL, 2003) at 33.

27. Griffith CJ’s famous judgment in Butt v McDonald (1896) 7 QLJ 68, for example, has been referred to more than 15 times by Australian superior courts since 2010.

28. More significant Griffith opinions, which remain the subject of legal professional privilege, are held in the office of the Crown Solicitor.

29. For a history of the firm, by a long-serving senior partner, see GO Morris Feez Ruthning: The First 100 Years (2004) (http://www.lexscripta.com/articles/FR.html).

30. Public Notice, Brisbane Courier, 4 December 1911. The merged firm was initially known as Feez, Ruthning and Baynes.

31. Ross Johnson “Robert Little (1822-1890)” Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol 5 (MUP, 1974). A photography of Little and his family home “Whytecliffe” appears in the Concise History at 34.

32. Robert Little’s admission was moved by the Attorney-General, who introduced him to the Court as a “gentleman of respectability”: Sydney Morning Herald, 10 August 1846, at 2.

33. Brisbane Courier, 21 January 1890, at 4.

34. Queensland Government Statistician Historical Tables Demography 1823-2008 (http://www.oesr.qld.gov.au/products/tables/historical-tables-demography/index.php)

35. The 1846 editions of the Moreton Bay Courier suggest that there were earlier practices commenced by John Ocock and Thomas Adams.

36. Nan Phillips “Eyles Irwin Caulfield Browne (1819-1886)” Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol 3 (MUP, 1969).

37. Brisbane Courier, 21 January 1890, at 4.

38. George Harding (later Harding J) who arrived in Brisbane in 1866 and Eyles Browne were married to sisters.

39. Brisbane Courier, 20 November 1869, at 5. And see re The Bank of Queensland Limited (1870) 2 QSCR 113.

40. Griffith’s relationship with the firm appears to have become closer after Harding was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1879. See, for example, King & Sons v Co-operative Butchering Company, Brisbane Courier, 12 August 1879 at 3; and Spent v Australasian Joint Stock Bank, Brisbane Courier, 8 April 1880 at 3.

41. The position prior to 1887 remains uncertain because the Opinion Book from this period remains too fragile to inspect. In the period from 1887 to 1993, however, 17 of the 49 opinions from counsel are from Griffith.

42. For an outline of Mr Ruthning’s life, see his obituary in The Queenslander, 7 October 1916, at 40.

43. Supreme Court of Queensland, Roll of Solicitors, 11 March 1876.

44. Public Notice, Brisbane Courier, 27 January 1879, at 1.

45. Public Notice, The Queenslander, 18 November 1882, at 692.

46. Brisbane Courier, 3 October 1883, at 1.

47. Brisbane Courier, 21 December 1881, at 1.

48. HLE Ruthning Bills of Exchange Act 1884 (Watson Ferguson, 1884)

49. Public Notices, Brisbane Courier, 20 October 1888 at 11 and 2 February 1993 at 1. For a brief account of Mr Byram’s career, see his obituary in the Brisbane Courier, 18 March 1922 at 12.

50. Public Notices, Brisbane Courier, 29 October 1893 at 3 and 4 December 1911 at 2. For a brief account of Mr Jensen’s career, see his obituary in The Queenslander, 22 May 1915, at 15.

51. Brisbane Courier, 10 October 1899, at 8.

52. Supreme Court of Queensland, Roll of Solicitors, 5 December 1899.

53. The Queenslander, 22 May 1915, at 15.

54. For a brief outline of Macpherson’s career, see his obituary in the Brisbane Courier, 13 September 1913, at 6.

55. Supreme Court of Queensland, Roll of Solicitors, 8 Sept 1865; Brisbane Courier, 22 September 1866 at 3.

56. Cairns Post, 25 September 1913, at 2.

57. Brisbane Courier, 13 September 1913, at 6.

58. See, for example, Hugh v Cribb, Brisbane Courier, 15 December 1868 at 2.

59. The first reported case is re Loudon (1870) 2 QSCR 70, when Griffith (instructed by Macpherson) appeared unsuccessfully in the Full Court against Harding (instructed by Little & Browne).

60. Reported cases include Hobbs v Municipality of Brisbane (1876) 4 QSCR 214 and Brisbane Municipal Council v Watson (1883) 1 QLJ 127. In the Opinion Books of this firm, numerous opinions were prepared by Griffith in matters for the Council.

61. P.Macpherson The Insolvency Act 1874 (Watson, 1874); G.Harding & P.Macpherson The Acts and Rules Relating to Insolvency (Watson Ferguson, 1887).

62. From 1884, the firm became known for a time as Macpherson and Miskin. However, in 1891, Miskin left the firm in unusual circumstances. He was reported to have left the Colony “without leaving any indication of his intended movements”: The Queenslander, 30 January 1892 at 234. After a time, he returned to practice in Rockhampton, where he remained until his death in 1913: Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, 15 October 1913, at 6.

63. Brisbane Courier, 20 April 1885, at 8.

64. Brisbane Courier, 2 April 1885, at 2.

65. Feez was admitted as a solicitor on 1 December 1885: Brisbane Courier, 2 December 1885, at 5. His appearances, as a solicitor from the offices of Macpherson and Miskin, begin to be mentioned in 1886: eg Brisbane Courier, 11 May 1886, at 4.

66. See JCH Gill “Adolph Frederick Feez (1854-1944)” and “Arthur Herman Feez (1860-1935)” Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol 8 (MUP) 1981. And see Brisbane Courier, 17 October 1944, at 4.

67. Brisbane Courier 16 December 1886 at 7.

68. As solicitor for the Brisbane Municipal Council, the firm was also involved in two cases which went on to the Privy Council: Martin v Muncipality of Brisbane (1893) 5 QLJ 3 (FC); [1894] AC 249 (PC); Clark & Fauset v Muncipality of Brisbane (1896) 6 QLJ 131 (FC — PC unreported Brisbane Courier, 9 April 1896, at 6).

69. Brisbane Courier, 14 February 1898, at 4.

70. Supreme Court Library Act 1968 (Qld) s.7A.

71. There are 456 opinions in the four volumes which are available for inspection, with an estimated 150 further opinions in Opinion Book No 1.

72. A.D.Graham The Life of Sir Samuel Griffith (Powells & Pughs, 1939) at 87, 93.

73. Ibid.

74. re Bridgeman (1869).

75. Queensland was one of the first colonies to adopt the Torrens system of land registration, with the enactment of the Real Property Act 1861 (Qld).

76. Ex parte Bank of Australasia (1893)..

77. For an account of the swearing in, on 14 March 1893, see Brisbane Courier, 15 March 1893, at 5.

78. A rare exception to this practice was, re McManus’s Will (1885) , where Griffith concluded “it is impossible to be confident as to the effect of the Will until the question has been decided by the Court.”

79. Ex parte Muncipality of Brisbane (1878).

80. AD Graham, op cit, at 60.

81. eg ex parte Union Bank (1886), which refers to the related case of Union Bank v Echlin (1886).

82. re Landsborough Wills (1886) which refers to the unreported case of Bright v Attorney General, Brisbane Courier, 16 Dec 1873.

83. ex parte Brisbane (1880).

84. ex parte Brisbane (1891)

85. ex parte DL Brown & Co (1883)

86. ex parte Brisbane Newspaper Company Limited (1889)

87. re Interest of Husband in Wife’s Lands (1886)

88. ex parte O’Brien (1885)

89. ex parte Stenson (1889)

90. Brisbane Courier, 8 September 1885, at 3.

91. Brisbane Courier, 17 March 1885, at 4.

92. ex part Brisbane re stoppage of traffic by Judge of Supreme Court (1885).

93. ex part Bank of Australasia re the Will of Hon W Graham (1892)

94. Turner v Kent (1891)

95. re Swan’s Will; ex parte Gailey and Ewing (1891). James Swan was a former editor of the Brisbane Courier and Mayor of Brisbane.

96. ex parte Trustees of EIC Browne (1888)