In Pharmacy Board of Australia v. Tavakol [2014] QCAT 112 the Queensland Civil Administration Tribunal dealt with submissions by each of the Pharmacy Board and the Registrant that, to varying extents between them, a proposed suspension of the Registrant’s registration should be suspended in whole or in part.

The Tribunal noted that neither party had made any submission identifying a source of power or even asserting explicitly that the Tribunal had the power when ordering the suspension of a Registrant under section 196 of the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Qld) to order that the suspension be suspended either in whole or in part. In the absence of any authority determining the question, the Tribunal proceeded to examine the issue, without the benefit of such submissions.

The Tribunal noted that under the predecessor Act, the Health Practitioner’s (Disciplinary Proceedings) Act 1999 (Qld), there was an express power to order that a suspension of a practitioner’s registration be suspended, wholly or in part. Further, as the Tribunal noted, the statutory provisions of that earlier Act provided a clear regime identifying what events might trigger the Tribunal revisiting the original suspension subsequent to making the order. Indeed the power existed for the Tribunal to suspend the operation of a range of decisions made as disciplinary action with respect to a practitioner against whom a disciplinary ground had been established.

The Tribunal noted that under the earlier Act the suspension was only authorised if the Tribunal was persuaded that it was appropriate in the circumstances. The Tribunal was required to specify the period during which, if the Registrant was subject to disciplinary action by the Tribunal, he or she might be further dealt with concerning the original disciplinary action. Where the Tribunal had found a ground for disciplinary action within the specified time period, the Tribunal could impose the originally suspended decision or a part of it. It could in the alternative decide to extend the period of the suspended decision by up to one year.

So, the Tribunal determined, the earlier Act not only expressly provided for the suspension of decisions, but provided a detailed mechanism for dealing with those matters. In contrast, the National Law did not confer express authority upon the Tribunal to suspend the operation of the decision, nor provided any mechanism by which any further proceedings might be taken concerning the original decision the subject of the suspension order.

The Tribunal, unsurprisingly in those circumstances, concluded that there was no power to order a “suspended suspension”.

The Tribunal’s attention was not drawn to section 198 of the National Law. It provides:

‘198 Relationship with Act establishing responsible tribunal

This Division applies despite any provision to the contrary of the Act that establishes the responsible tribunal but does not otherwise limit that Act.’

Reference to that provision brings one to section 114 of the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal Act 2009. It provides:

‘114 Conditions and ancillary orders and directions

The tribunal’s power to make a decision in a proceeding (the primary power) includes a powerâ

(a) to impose conditions on the decision; and

Example of a conditionâ

that something required to be done by the decision be done within a stated period

(b) to make an ancillary order or direction the tribunal considers appropriate for achieving the purpose for which the tribunal may exercise the primary power.

Examples of ancillary orders or directionsâ

- an order adjourning the proceeding

- an order or direction that a person give an undertaking to the tribunal.’

Section 3 of the National Law provides the objectives and guiding principles of the National Law, relevant to section 114(b) above. It includes the provision of registration and accreditation schemes for the regulation of health practitioners. More specifically the scheme includes amongst its objectives to provide for the protection of the public by ensuring that only health practitioners who are suitably trained and qualified to practice in a competent and ethical manner are registered, and to facilitate access to services provided by health practitioners in accordance with the public interest. Amongst the guiding principles for the scheme, it is said that restrictions on the practice of a health professional are only to be imposed if it is necessary to ensure health services are provided safely and are of an appropriate quality.

Reference to all of these provisions shows that while there is no longer a provision that quite so definitively establishes the power of the Tribunal to order that a suspension, amongst other disciplinary action, be suspended, the terms of section 114 are, in the opinion of the author, broad enough to allow the Tribunal the make such an order and to fashion the order in a way that somewhat replicates the scheme provided for under the former legislation. It is noted that neither of the proposals put before the Tribunal in Tavakol sought to do that. They would have left it as a mystery as to what was to happen in the event that there was some disciplinary ground established to have occurred during the period of time in which the original suspension order was suspended.

A power to order a suspension of a disciplinary order made by the Tribunal under the National Law is an important ‘tool in the kit’ for the Tribunal in achieving the objectives of the legislation in many cases, where the balance needs to be struck between ensuring adequate standards of performance by health practitioners by the exercise of a power to suspend registration and the advancement of the public interest by ensuring that health practitioners are not unduly restricted from practicing their profession. It is by reference to those objectives and guiding principles specified in the National Law that the power to act under section 114 of the QCAT Act in this way can be identified, in an appropriate case, as was the position under the earlier Act.

The opportunity may well arise in the foreseeable future for the Tribunal to be invited to reconsider the matter by reference to these other statutory provisions and on the basis of a proposed order replicating the scheme provided for under the 1999 Act.

Geoffrey Diehm QC

Barristers took to a Brisbane stage during Law Week in May to help give Queenslanders a fun and informative look at law and justice.

Held nationally each year, Law Week aims to promote public understanding of the law and its role in society. Brisbane’s Queen Street Mall hosted the major event on 16 May.

The packed program featured free presentations, displays, entertainment, information and demonstrations, in a move away from the court-based open days held in past years.

Joshua Jones (Murray Gleeson Chambers) and Kate McMahon (Legal Aid Queensland) joined Queensland University of Technology law students on the mall stage for the mock trial of the character Alice, for murdering the Jabberwocky in Wonderland.

Lunchtime crowds were entertained by an impressive performance by the Crown Law choir, as well as demonstrations from Queensland Police dogs and corrective services drug detection dogs.

A captive audience watched the crime scene mapping and fingerprinting demonstrations and information sessions were held on common legal problems, youth law, scams, crime prevention, electrical safety in the home and family history research.

Visitors posed as a judge or police officer in the photo booth and got a closer look at police and prison vehicles while the Bar Association of Queensland and other agencies had displays providing information about legal services.

Other Law Week events held around Queensland included mooting competitions, courthouse tours and information displays.

The Queensland Legal Walk — held in Brisbane, Sunshine Coast, Mackay, Townsville and Cairns on 13 May — raised more than $50,000 to help the Queensland Public Interest Legal Clearing House (QPILCH) continue to provide free legal help.

See more at www.lawweek.qld.gov.au; the Law Week facebook page www.facebook.com/LawWeekQueensland or on Twitter @JusticeQLD or Instagram @lawweekqld.

Photos by Damian Caniglia

Attorney-General and Minister for Justice Jarrod Bleijie addresses the lunchtime crowd at the Law Week mall event.

Crown Law choir entertains mallgoers.

Attorney-General Jarrod Bleijie with Queensland Corrective Services drug detection dog Jessie.

Joshua Jones (left) prosecutes the case against ‘Alice’ (Selina Iderjac – right) as witness ‘the Red Queen’ (Hasting Lai – QUT) looks on.

Mock trial participants ‘Alice’ (Selina Iderjac – left), witness ‘the Mad Hatter’ (Anna Storer – QUT) and defence barrister Kate McMahon (Legal Aid Queensland).

Fairytale ending: mock trial participants (from left) Prosecutor Joshua Jones (Murray Gleeson Chambers), ‘the Red Queen’ (Hasting Lai – QUT), ‘Alice’ (Selina Iderjac), ‘Mad Hatter’ (Anna Storer – QUT) and defence barrister Kate McMahon (Legal Aid Queensland).

The ABA Journal website can be accessed at http://www.abajournal.com/

A selection of recent items are listed below and members are invited to explore the vast array of articles that are continually posted.

“Scandalous” Class Action Settlement Thrown Out

View blog

Judge on paid leave, seeking counseling after reported fight with public defender outside courtroom

View blog

Members practising in the workers’ compensation field will be interested in a recent article appearing in the Australian relating to the proposed expansion of the Comcare scheme, which will have the effect of allowing many more nationally operating companies to join the national scheme. The article appears at the following link:

www.theaustralian.com.au/business/push-to-expand-comcare/story-e6frg8zx-1226949903039#

The Australian Bar Association Advocacy Training Council will be holding the 2014 ABA Appellate Advocacy Course in Sydney from 12 to 14 September 2014.

Applications are now open and there are limited positions available.

The course is for Barristers with a minimum of 8 years’ experience at the private Bar. The total cost of the course is $2,300 (incl GST) with Registrations closing on 8 August 2014 unless all positions have been filled before then.

This is an excellent course and a great opportunity for barristers to hone their skills. Readers will recall the excellent review of the 2013 course by Sue Brown QC that appeared in Issue #66: see Through the Looking Glass

For more information on the 2014 course, click on the link below.

advocacytraining.com.au

The inaugural Far North Queensland Law Association Mooting Competition took place on Thursday 15 May 2014 as part of Law Week celebrations. Justice Henry, Judge Harrison and Magistrate Pearson presided. The participants were Miles Dickson (barrister – DPP), Shannon-Lee Elcoate (solicitor – DPP), Andrew Scott (solicitor – MacDonnells Law) and Michelle Kelly (solicitor – MacDonnells Law) with the DPP taking out the competition.

Current Legal Issues Seminar Series

Banco Court, Supreme Court of Queensland

8 May 2014

It is a pleasure to have been invited to this Seminar. The pleasure is mixed with terror. One source of pleasure is the company of my good friend Stefan Vogenauer. But he is also a source of terror. For in him you have a world expert. From me you will get only antediluvian prejudices, though they are the prejudices of someone who has read enough statutes to satisfy the needs of a lifetime.

It is a particular pleasure to be speaking in Brisbane — near Ipswich, from which two of the greatest of High Court justices hailed. From one point of view they are the greatest, in view of the unusual problems they experienced.

Sir S amuel Griffith, as first Chief Justice of the High Court, faced two difficulties. The first difficulty was the need to ensure that the High Court gained the respect of State Supreme Court judges. Some of them had opposed the creation of the High Court. They would have preferred that all appeals continued to go, as they had before 1903, straight from Supreme Courts to the Privy Council. In due course the Court, unlike Biblical prophets, did receive honour in its own country. The second difficulty was the need to ensure that the High Court gained the respect of the Privy Council, particularly in constitutional law. This it did, but only after exchanges of hostile fire between Sir Samuel and Lord Halsbury.

amuel Griffith, as first Chief Justice of the High Court, faced two difficulties. The first difficulty was the need to ensure that the High Court gained the respect of State Supreme Court judges. Some of them had opposed the creation of the High Court. They would have preferred that all appeals continued to go, as they had before 1903, straight from Supreme Courts to the Privy Council. In due course the Court, unlike Biblical prophets, did receive honour in its own country. The second difficulty was the need to ensure that the High Court gained the respect of the Privy Council, particularly in constitutional law. This it did, but only after exchanges of hostile fire between Sir Samuel and Lord Halsbury.

Sir Harry Gibbs, on the other hand, faced the unusual difficulties of working out the Court’s best response to the numerous travails through which Justice Murphy had to pass during his last few years on the Court. It is difficult to imagine how anyone could have handled matters better.

The Stature of Mr Justice O’Connor

I want to structure my remarks around the views of one of Sir Samuel’s colleagues — Mr Justice O’Connor, who was, with Griffith CJ and Barton J, one of the three founding justices. For able though Sir Samuel was, Sir Owen Dixon seemed to rate Mr Justice O’Connor more highly. Sir Owen said in 1964 in his address on retiring from the High Court that Griffith CJ had “a dominant legal mind … a legal mind of the Austinian age”.1 Austin’s key doctrine, of course, was that law was a command backed by a sanction — a doctrine which Griffith CJ’s masterful approach to legal problems may not have found unsympathetic. But Sir Owen went on: “I think — speaking for myself — that Mr Justice O’Connor’s work has lived better than that of anybody else of the earlier times”.2 That direct tribute is the more forceful for two reasons. One is that Sir Owen Dixon on that occasion passed on the view of Sir Leo Cussen, though apparently without agreeing with it, that “Barton’s judgments were the best, … they had more philosophy in them, more understanding of what a Constitution was about, more sagacity; … they were well written and … they were extremely good”.3 The other is that praise was a somewhat rare quality in Sir Owen’s brilliant but sombre and rather tart oration. Further, Sir Anthony Mason agreed with Sir Owen Dixon’s view of Mr Justice O’Connor, at least in relation to the foundation justices, for he thought Isaacs J superior in influence and output.4

Mr Justice O’Connor was certainly a formidable figure in our history. He was a member of the New South Wales legislature. He was a key framer of the Constitution. He was leader of the government in the Senate. He was a prominent Catholic in a sectarian age. He was a Fenian in an age of Empire. He was universally respected for his calmness, courtesy and probity. At the end of his relatively short tenure, he was a tragic figure as he tried to struggle though nephritis and worked himself to death — for in those days there was no judicial pension to support his family after his premature demise.

Mr Justice O’Connor’s theories of statutory construction appear to be sound in every way, even now. But before they are explained, it is necessary to indicate the point of view from which this lecture approaches the problem.

The Central Theme

The Central Theme

The central assumption of this lecture is that judges should construe legislation in order to ascertain what it actually provides, quite independently of their personal opinions about what it ought to have provided.

In jurisdictions influenced by English law, whether they are jurisdictions governed by a written constitution or not, the law is made or declared by judges. Their view of it — what we call “the common law” — prevails unless there is a provision in any applicable constitution, or in any applicable statute, to the contrary. The phenomenon of “judicial activism” is commonly seen as arising mainly in relation to constitutional law or common law.

One problem in a judicially activist approach to a constitution is that constitutions are usually very hard to amend. Hence judicial constructions which are seen as wrong, even badly wrong, can for practical purposes be incapable of correction except by later judges. Our Commonwealth Constitution, of course, is generally seen as very hard to amend by the legislative and popular processes mandated by s 128.

A judicially activist approach to the common law, on the other hand, can be corrected not only by later judges but also by the legislature. But correction can be difficult. Enlisting the aid of the legislature can sometimes be very hard. And the practice of ultimate appellate courts is to abstain from altering what prior authorities have decided unless they are thought to be not only plainly wrong but also productive of serious inconvenience.

Yet judicial activism can be as great a problem in relation to non-constitutional statutes as it is with constitutions and the common law. That is because statutes have no accepted meaning until the courts have construed them. Of course both the human agents of the government, and the governed themselves, have to act on what they take to be the statutory meaning even before any curial construction has taken place. In many instances what they understand to be the meaning is confirmed in due course by the courts. But this is not always so.

The courts, in other words, play an mediatory role between the governor — the legislature, the lawgiver, the commander — and the governed, to whom the laws are given. That mediatory role is in fact very great. Its significance is accentuated by the increasing number and range of statutes nowadays — what Lord Bingham of Cornhill unflatteringly called the “legislative hyperactivity”5 of the modern scene. Let us remember Bishop Hoadly’s sermon preached before King George I on 31 March 1717. The King probably did not understand it, having not long before arrived from Hanover, but in it Bishop Hoadly used words the fame of which is well deserved:

“Whoever hath an absolute authority to interpret any written or spoken laws, it is he who is truly the lawgiver, to all intents and purposes, and not the person who first wrote or spoke them.”

And of course our courts have an absolute authority to interpret all written or spoken laws. At the end of the day, the only relevant role in interpreting legislation is that of the courts. The interpretation of legislation is what the courts say it is. People may disagree with a particular interpretation. But they are bound by that interpretation. That is so whether they are legislators, officials or members of the public. There is no sanctuary in which the governed — or indeed the government — can hide away from the consequences of the interpretation. Nothing can be done about an inconvenient interpretation until some fresh step is taken — a change of mind in the courts or a new statute. That remains the case however much the interpretation rejected by the courts is favoured by the public, however much it is unanimously supported by governing elites, or however much it was carefully framed by those advising the executive and the legislature when the legislation was being prepared.

There are abuses, or risks of abuse, inherent in what Bishop Hoadly called “an absolute authority to interpret” the laws. For this “absolute authority” which the judiciary possesses gives it immense power in relation to statutes. You all know the trenchant phrases of Lord Acton which he used to Bishop Mandell Creighton about the latter’s History of the Popes. On 3 April 1887, he wrote a letter to Creighton to complain about the book’s failure to condemn the failings of the medieval papacy more vigorously. He said: “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.” Perhaps “greatness” is an expression which it is not appropriate to apply to judges. But if it is, there are, no doubt, some great judges — or judges who have been called great — who have been corrupted by power and who became bad men.

How far can principles of statutory construction control these risks of abuse and corruption? How far do the principles of statutory construction increase those risks?

Click here to download full article

Click here to download the handout

J D Heydon

2014 presents high income earners with some unique challenges due to changes announced in the Federal Budget that are as yet unlegislated tax law, in addition to the introduction of the 2% budget repair levy on 1 July 2014.

BAQ members must decide between:

- bringing forward expenses to reduce this year’s tax; or

- claiming the expenses in 2015 when the top marginal tax and levies will be 2.5% higher.

Members with incomes above $180,000 will need to consider their cost of funding to assess whether bringing forward deductions to this year with a top tax rate of 46.5% is more effective than reducing tax one year later at 49%.

Should you elect to minimise tax in the 2014 year there are a number of tax and superannuation initiatives worth considering. Please refer to our comprehensive Year End Tax and Superannuation Planning Guide for all the details.

Key tax and superannuation planning opportunities for BAQ members to consider include:

- Some expense prepayments will be available to BAQ members in the year they are paid, such as investment loan interest (12 months in advance only), insurance premiums etc.

- If you purchased a new car in 2013/14 year, you may be able to claim the first $5,000 as an expense this year. However, please note for cars purchased after 1 January 2014 that this deduction may be repealed when put before a new Senate on 1 July 2014. Amendments without penalty will be required if that occurs.

- If you have a Discretionary Trust for income streaming, consider which beneficiaries of your Trust will be presently entitled to the income or capital of the trust on or before June 30. A written direction should be made by 30 June. Failure to do so may result in income tax at the highest marginal tax rate in the Trust.

- If you are aged 60 or more you may make concessional superannuation contributions that are tax deductible up to your cap of $35,000. Also if you were at least 59 on 30 June 2013 i.e. you will be 60 before 30 June 2014, you can also contribute up to $35,000 as a concessional contribution. For all others under aged 60 the concessional contribution cap is $25,000. If you decide to contribute pre-tax income into your superannuation fund up to these limits the contributions will be tax deductible to you and taxed at only 15% within the superannuation fund.

- Barristers who are earning more than $300,000 per financial year should be aware of an additional 15% contributions tax levied on contributions of certain high income earners. This is called ‘Division 293 Tax’, if you would like additional information on how this affects your financial situation please contact us. Briefly, if you are paying tax at the top marginal tax rate on 46.5% a 30% tax on deducted contributions still constitutes a tax saving of 16.5%.

- If you have decided or have been advised to make substantial non-concessional contributions to superannuation, carefully consider the timing of this. The annual non-concessional contribution (NCC) limits are increasing on 1 July to $180,000 up from $150,000 and therefore using the “bring forward rule” superannuants under age 65 can make 3 x the annual NCC limit in any one 3 year period. Using the “bring forward rule” before June 30 you’ll have a limit of $450,000, delaying it until 1 July you’ll have a limit of $540,000.

If you require personal advice on any of these planning opportunities please contact Tim Taylor or Jamie Towers on 07 3218 3900 at Hanrick Curran on matters of Tax and Andrew Fleming or Michael Borjesson at Wilson HTM who are AFS licensed on matters of Superannuation on 07 3212 1326.

Book now to schedule your Pre FYE Tax, Superannuation or Investment Review. Identify other opportunities you could be actioning before 30 June to improve your after tax position by speaking with Hanrick Curran and Wilson HTM Advisers. Contact Hollie Spencer to arrange a time with our experts.

The Supreme Court Library is much more than just a repository of books, with its growing collection of legal research tools now available to you online via the Library catalogue.

In addition to our own Caselaw, Caselaw Plus and Queensland Sentencing Information Service publications, legal practitioners who register with the Library can also enjoy free access to a range of online subscription resources from commercial publishers.

To access the LexisNexis, Westlaw (Australian and International), CCH (IntelliConnect) and AGIS Plus Text databases, practitioners can visit the Library in Brisbane, Cairns, Townsville or Rockhampton. Our public PCs are available (no booking required) during normal opening hours in each of these locations. While onsite, users can access the full range of online legal resources, printing facilities as well as, of course, our print collections.

![Catalogue_Online Resources[1].PNG](https://www.hearsay.org.au/carbon/assets/2013/03/Catalogue_Online-Resources1.PNG)

Registered members can also use their SCL login to access a range of online resources from their own PC. Some of the research tools that are available remotely via the Library catalogue include:

- Hein Online: more than 100 million pages of legal history available in an online, fully-searchable, image-based format. It provides comprehensive coverage of more than 1,800 law and law-related periodicals.

- Legaltrac: provides indexing for approximately 875 titles including major law reviews, legal newspapers, bar association journals and international legal journals. It also contains law related articles from over 1,000 additional business and general interest titles.

- Oxford Suite: an extensive collection of online works, including dictionaries, encyclopaedias and other leading reference titles, journals, reports on international law, and criminology and criminal justice handbooks.

- The Making of Modern Law: database of more than 21,000 Anglo-American legal works published during the period 1800 to 1926.

- Eighteenth Century Collections Online: law component of the Collection from the digital edition of The Eighteenth Century microfilm set, which aimed to include every significant English-language and foreign language title printed in the United Kingdom, and other works published in the Americas, between 1701 and 1800.

- Thomson-Reuters Collected Works Library: an e-book collection of 41 classic Australian legal texts.

- Who’s Who and Who Was Who: contains over 33,000 short biographies, continually updated, of living noteworthy and influential individuals from all walks of life, worldwide. The online database also includes over 100,000 entries from the archives of Who’s Who dating back to 1898 (‘the definitive roll-call of the last 150 years of British history’).

- Max Planck Encyclopaedia of Public International Law: covers the central and essential topics in international law.

- Australian Law Dictionary: reference tool which facilitates familiarity with and knowledge of Australian legal terms.

Due to special licensing arrangements, sole practitioners can also access these titles remotely:

- TimeBase Point-in-time: access to relevant legislation in force on a specified date in the areas of criminal law, corporations law, employment law, GST, income tax, intellectual property, trade practices, customs and excise, migration and student assistance.

- TimeBase LawOne: access to full text current legislation and repealed legislation for all nine Australian jurisdictions, in some cases as far back as 1994.

For more information about registering or accessing our online legal resources, contact Brendon Copley, Information Services Librarian, on (07) 3247 4373 or at reference@sclqld.org.au.

catalogue.sclqld.org.au

David Bratchford

Supreme Court Librarian

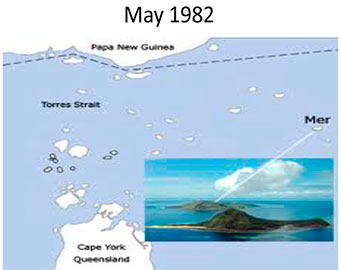

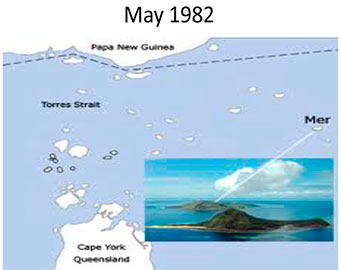

May 1982

May 1982

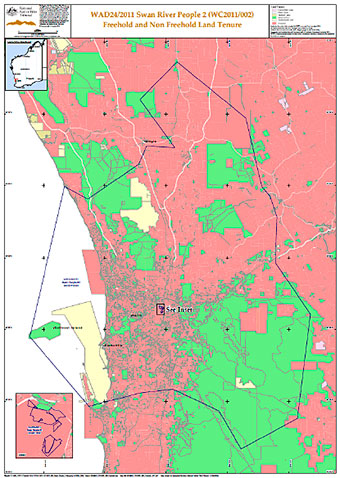

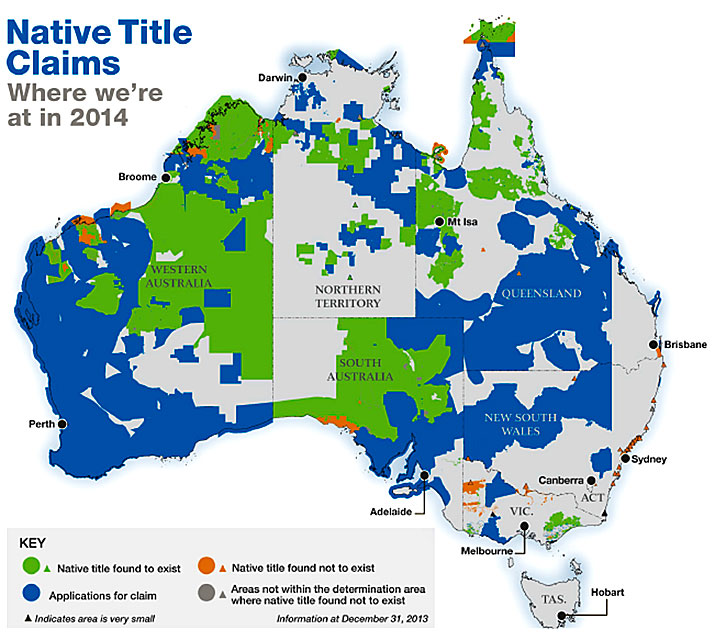

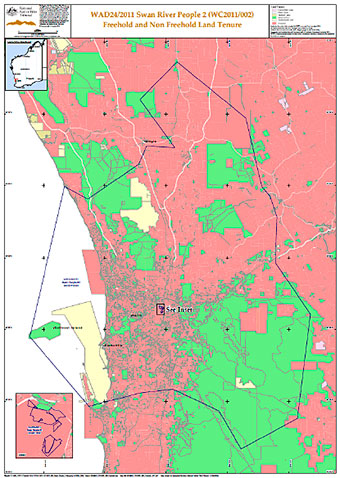

Lets start then in May 1982 when Eddie Mabo and four other Meriam people of the Murray Islands in the Torres Strait began an action in the High Court of Australia seeking confirmation of their traditional land rights.

They claimed that Murray Island (Mer) and surrounding islands and reefs had been continuously inhabited and exclusively possessed by the Meriam people who lived in permanent communities with their own social and political organisation.

They conceded that the British Crown in the form of the colony of Queensland became sovereign of the islands when they were annexed in 1879.

Nevertheless they claimed continued enjoyment of their land rights and that these had not been validly extinguished by the sovereign.

They sought recognition of these continuing rights from the Australian legal system. The case was heard over ten years through both the High Court and the Queensland Supreme Court.

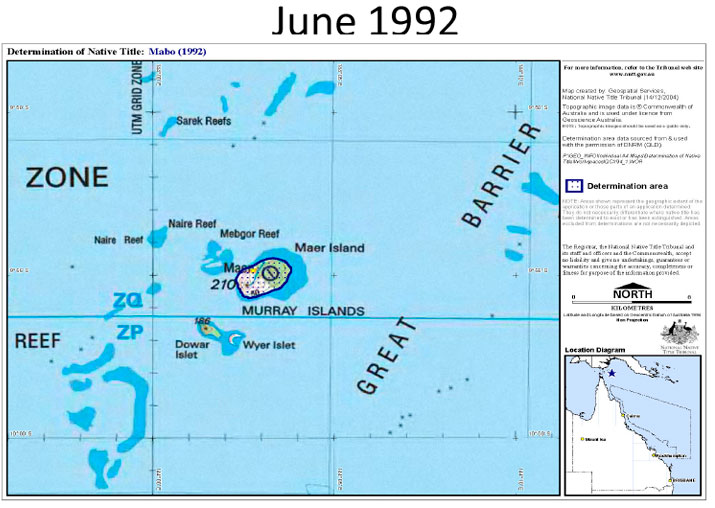

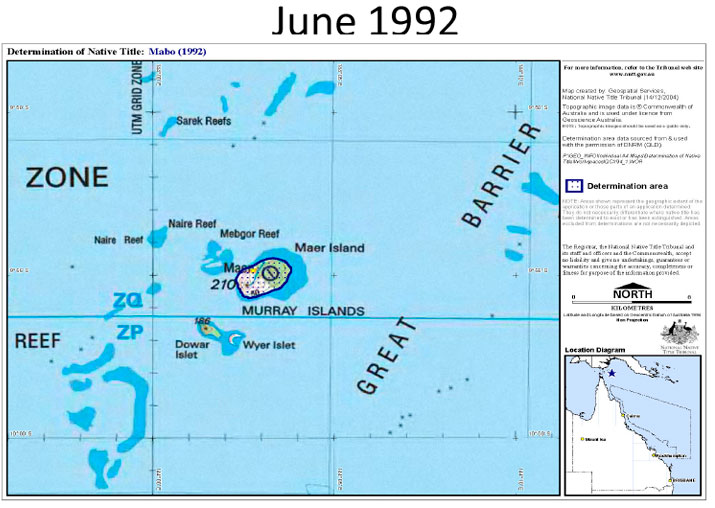

June 1992

On 3 June 1992, the High Court by a majority of six to one upheld the claim and ruled that the lands of this continent were not terra nullius or land belonging to no-one when European settlement occurred, and that the Meriam people were “entitled as against the whole world to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of (most of) the lands of the Murray Islands”.

The decision struck down the doctrine that Australia was terra nullius – a land belonging to no-one.

The High Court judgment found that native title rights survived settlement, though subject to the sovereignty of the Crown. The judgment contained statements to the effect that it could not perpetuate a view of the common law which is unjust, does not respect all Australians as equal before the law, is out of step with international human rights norms, and is inconsistent with historical reality.

The High Court recognised the fact that Aboriginal people had lived in Australia for thousands of years and enjoyed rights to their land according to their own laws and customs. They had been dispossessed of their lands piece by piece as the colony grew and that very dispossession underwrote the development of Australia into a nation.

The decision was attacked by some commentators as being a High Court “adventure”.

The decision was attacked by some commentators as being a High Court “adventure”.

But it was defended by then Chief Justice Mason in the following terms:

Far from being an adventure on the part of the High Court, the decision reflects what’s happened in the great common law jurisdictions of the world and in the International Court, except that in Australia it’s happened later than it’s happened anywhere else.

Mason A, “Putting Mabo in Perspective” (1993) Australian Lawyer 23, at 23

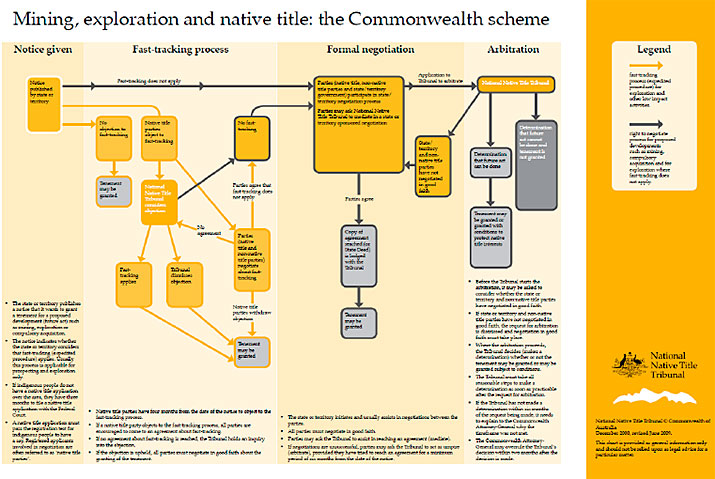

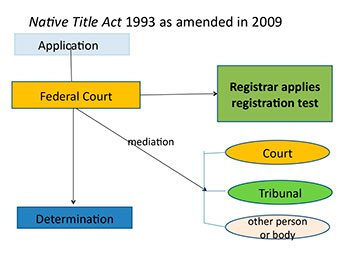

The Native Title Act 1993 was part of the Commonwealth Government’s response to the 1992 Mabo decision.

The Native Title Act 1993 was part of the Commonwealth Government’s response to the 1992 Mabo decision.

The Act came into operation on 1 July 1994.

It provided for a systematic legal framework to deal with matters affecting native title. The Act favoured resolution of native title matters by agreement.

Mabo v Queensland No 2 (1992) 175 CLR 1 at [83] per Brennan J

Native title to particular land (whether classified by the common law as proprietory, or otherwise), its incidents and the persons entitled thereto are ascertained according to the laws and customs of the indigenous people who, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land.

Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) S223(1)

Common law rights and interests

223(1) The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

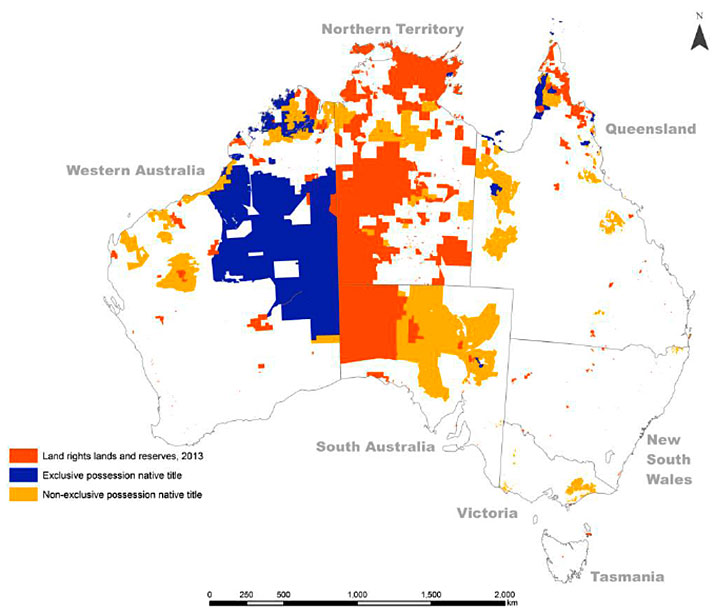

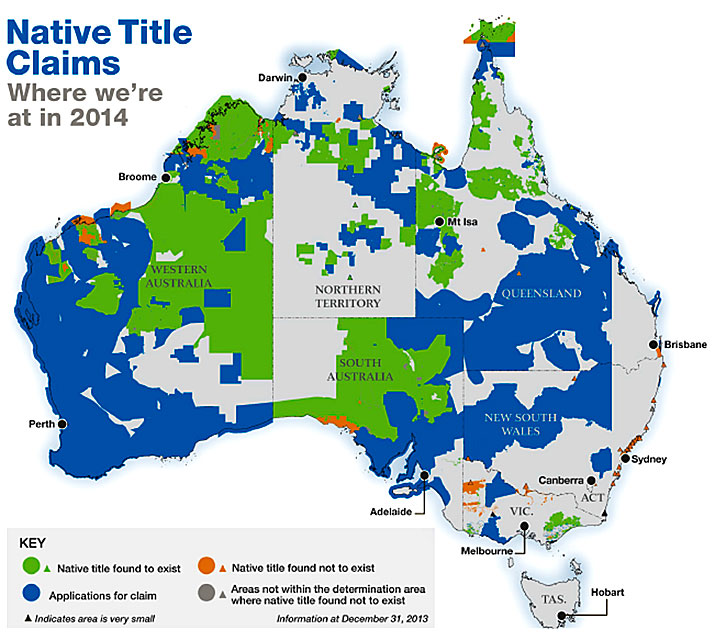

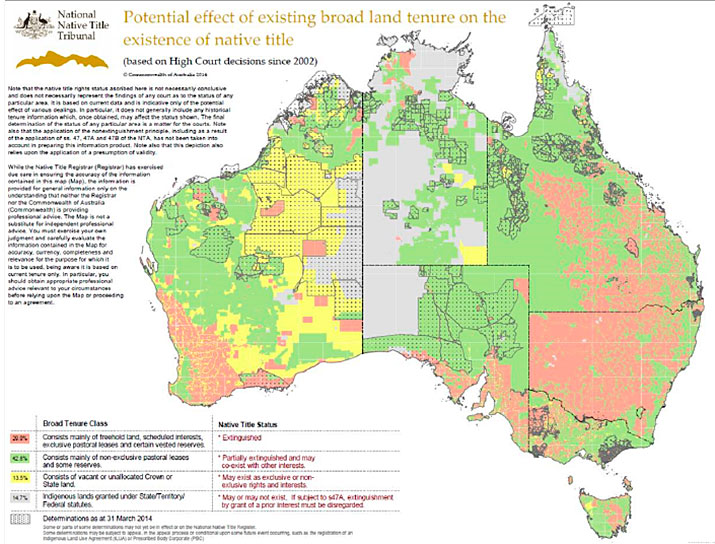

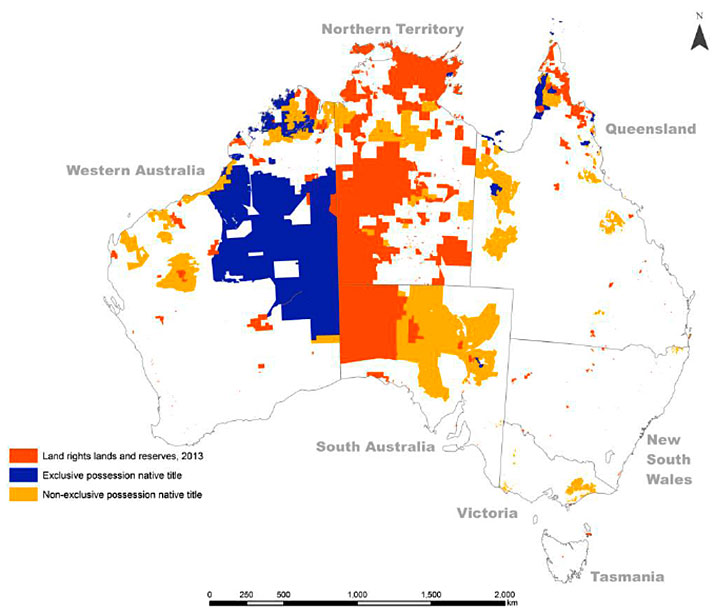

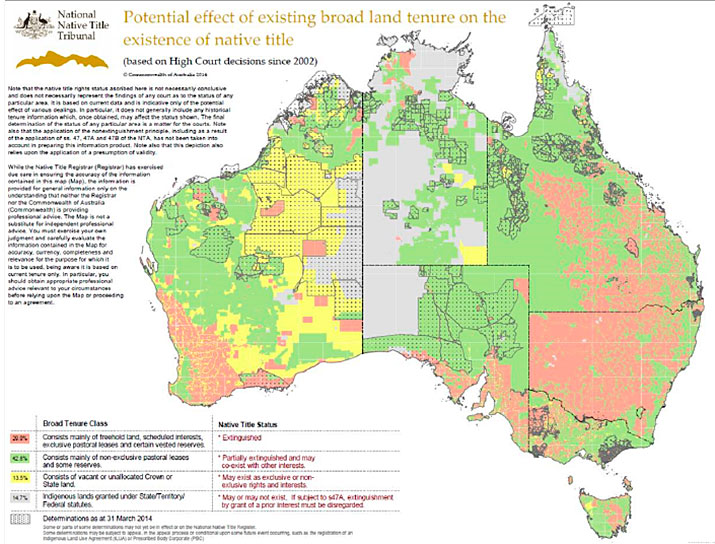

Where native title can exist

Where native title cannot exist

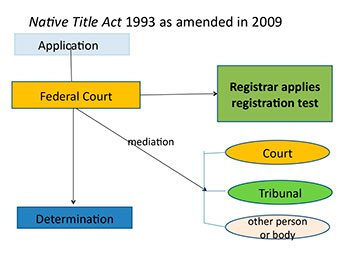

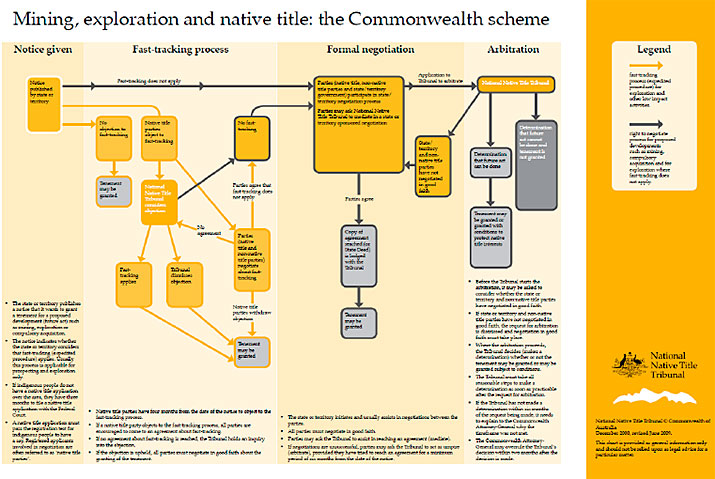

Then followed amendments in 2009 which provided that both the Court and the Tribunal may mediate in respect of an application and, also that another ‘appropriate person or body’ may mediate. The decision as to who should mediate was a matter for the Court.

Then followed amendments in 2009 which provided that both the Court and the Tribunal may mediate in respect of an application and, also that another ‘appropriate person or body’ may mediate. The decision as to who should mediate was a matter for the Court.

The change meant that, rather than automatically referring every case to the Tribunal for mediation, it was for the Court to decide which individual or body should mediate each matter.

Other little discussed amendments in 2009 are those which enable the Court (rather than the President) to direct the Tribunal to hold a native title application inquiry, or refer certain native title issues to the Tribunal for review.

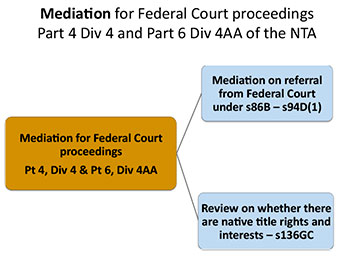

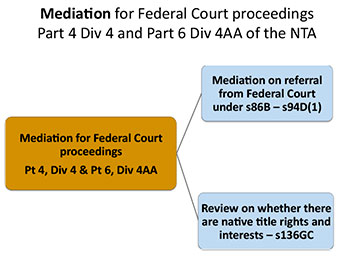

Moving on to the mediation function for Federal Court proceedings:

Moving on to the mediation function for Federal Court proceedings:

It is not the case that the Tribunal can have no role in respect of claims mediation. The gravamen of the amendments is that the Federal Court now has control over the claims process — and can itself decide how mediation will occur.

s 94D(1) is concerned with mediation on referral from Court under s 86B

Reminder that S 86B provides for Court referral of a s 61 application to an appropriate person or body for mediation – note this does not exclude referral to a member of the NNTT

S 94D(2) provides that if mediator is the NNTT, a member must conduct the mediation.

Subject to an order made under s 86B(5C) a person conducting a mediation may be assisted:

If an NNTT member by another member or member of staff of NNTT

In any other case, by such individuals as the person considers appropriate

[S 86B(5C) permits the court to make orders about whether the person who is to conduct the mediation may be assisted by another person]

Review on Whether there are Native Title Rights and Interests

S136GC — provides for referral from the Court for review by the Tribunal of the issue whether a native title claim group who is a party to a proceeding holds native title rights and interests as defined in s 223(1) in relation to land and waters within an area that is the subject of the proceeding:

The referral can be of the Court’s own motion,

or

if it arises in the course of mediation and the mediator requests the Court to refer the issue for review

The mediator must consider the review would assist parties to reach agreement on any of the matters referred to in ss 86A(1)

s 136GE — report to be provided setting out findings (not binding) – consistent with it being a report prepared for mediation

Matters referred to in Native Title Act, s86A(1)

- whether native title exists or existed in the area of the application

- if it exists or existed:

- who holds/held the native title

- the nature, extent and manner of exercise of the native title rights and interests

- the nature and extent of other interests in the area

- the relationship between native title and other interests

- whether the native title rights and interests confer or conferred possession, occupation, use and enjoyment to the exclusion of all others

Native title application inquiries

The Federal Court may direct the Tribunal to hold an inquiry in relation to a matter or an issue relevant to the determination of native title under section 225 (s138B(1))

This step can be taken

(a) by the Court on its own motion; or

(b) at the request of a party to a proceeding; or

(c) at the request of the person conducting the mediation

Native title application report

The Tribunal may make recommendations in the report. However, any such recommendations are not binding between any of the parties to the inquiry (s163A)

The Tribunal may make recommendations in the report. However, any such recommendations are not binding between any of the parties to the inquiry (s163A)

The rationale of giving the one body, the Federal Court, the control over the over the direction of each case, from start to end, was that the Court could more readily identify the opportunities available to resolve each claim. The new approach was intended to improve the operation of the native title system by encouraging more negotiated settlements of native title claims, and encouraging the Court and parties to find new ways to resolve claims.One of the ways the Court and parties can utilize the Tribunal to assist with the resolution of claims is to refer issues relevant to the determination of native title for inquiry.This could operate somewhat like a referee report in general litigation and could assist in resolving overlaps, and in investigating claim group membership where appropriate, in native title litigation. One of the perceived barriers to use of the Tribunal’s inquiry function is the non-binding nature of recommendations in made in a native title application inquiry report (s 163A) —

Evidence and findings in other proceedings — s86(2)

Subject to s82(1) the Federal Court:

must consider whether to receive into evidence the transcript of evidence from a native title application inquiry; and

may draw any conclusions of fact from that transcript that it thinks proper; and

may adopt any recommendation, finding, decision or determination of the NNTT in relation to the inquiry

But see s 86(2)

But see s 86(2)

permitting court to:

Draw any conclusions from transcript of evidence from a native title application inquiry

adopt any recommendation of the NNTT in relation to an inquiry.

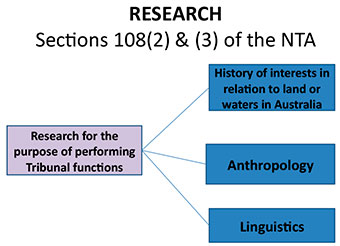

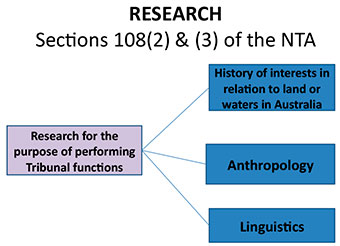

The Tribunal may carry out research for the purpose of performing its functions, including into:

The history of interests in relation to land or waters in Australia; or Anthropology; or Linguistics.

If the Tribunal was exercising all of its functions conferred upon it by the Native Title Act our offices would look something like this.

Under-utilised functions of the NNTT

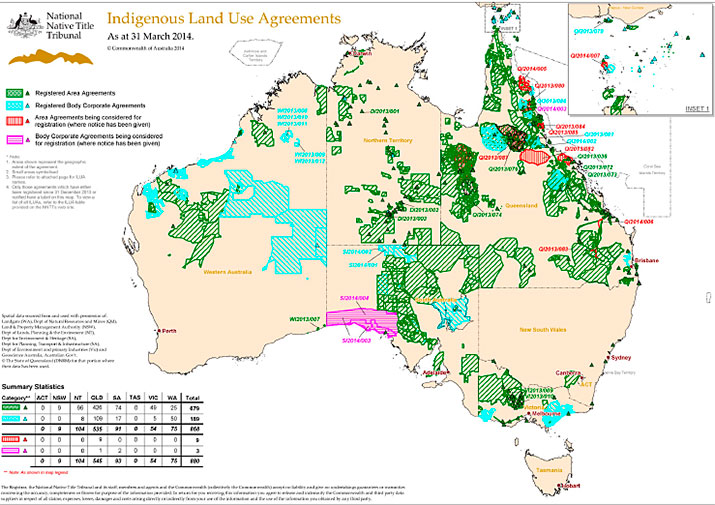

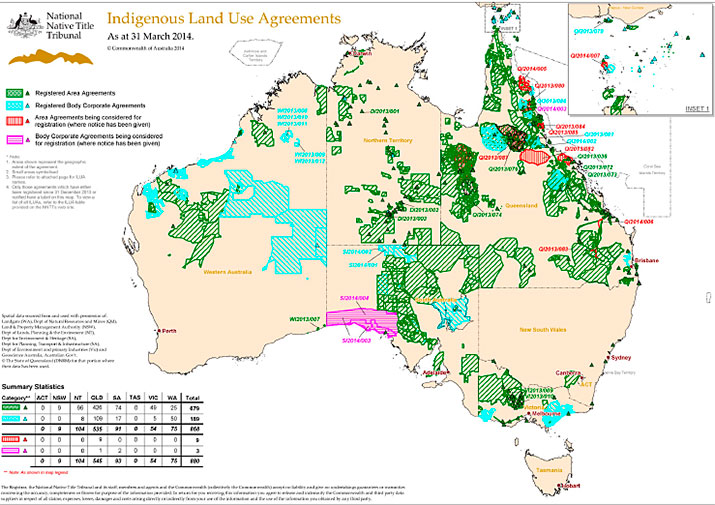

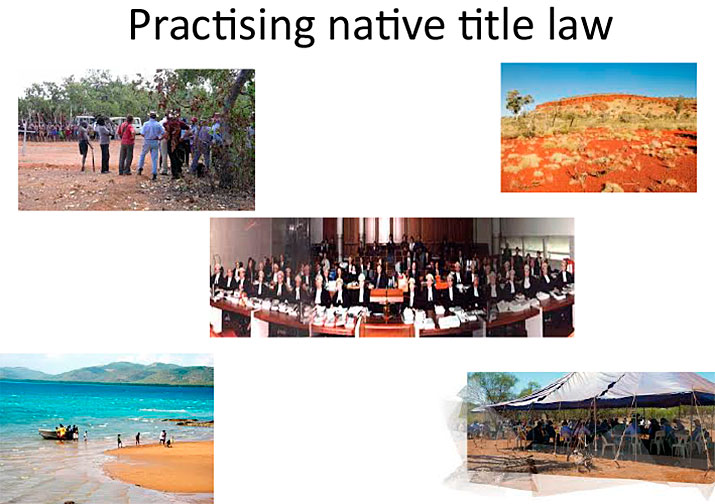

When practitioners think of the work done by the Tribunal, my best guess that they think of mediation and arbitration of future acts, and possibly facilitating Indigenous Land Use Agreements.

Indeed, when then Attorney-General the Hon Nicola Roxon announced the institutional reforms, she stated that the:

reform refocuses the resources of the Tribunal on its areas of strength, enabling greater focus on crucial functions relating to future land uses affecting native title

But there are many under-utilised, functions of the Tribunal including the inquiry and review functions now under the Court’s direction since the 2009 amendments.

To the best of my knowledge, these functions have never been used by the Tribunal.

Australian Native Title: References

- **Bartlett R, Native Title in Australia, 2nd ed., Butterworths, Sydney, 2004.

- Native Title News, Loose-leaf service, Butterworths, North Ryde, NSW.

- Strelein L, Compromised Jurisprudence: Native Title Cases since Mabo, 2nd ed., Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2009.

- Perry M and Lloyd S, Australian Native Title Law, Law Book Company, NSW, 2003.

- ** Refer to the ‘Native Title’ Chapters in the following books:

- McRae H, Nettheim G, Anthony T, Beacroft L, Brennan S, Davis M, Janke T, Indigenous Legal Issues: Commentary and Materials, 4th ed., Thomson Reuters Australia, NSW, 2009.

- Butt P, Land Law, 6th ed., Lawbook Co., Pyrmont, NSW, 2010.

- Webb E & Stephenson MA, Land Law, 3rd ed., LexisNexis Butterworths, Chatswood, NSW, 2009.

Additional readings:

- Secher U, Aboriginal Customary Law: A Source of Common Law Title to Land, Hart Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2014.

- Keon-Cohen B, A Mabo Memoir: Islan Kustom to Native Title, Zemvic Press, Malvern, Victoria, 2013.

- Eades D, Aboriginal Ways of Using English, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2013.

- Langton M & Longbottom J (eds.), Community Futures, Legal Architecture: Foundations for Indigenous peoples in the Global Mining Boom, London, Routledge, 2012.

- Bauman T & Glick L (eds.), The Limits of Change: Mabo and Native Title 20 Years On, AIATSIS Research Publications, Canberra, 2012.

- Strelein L (ed.), Dialogue about Land Justice: Papers from the National Native Title Conferences, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2010.

- Behrendt L, Cunneen C & Libesman T, Indigenous legal Relations in Australia, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, Victoria, 2009.

- Ritter D, Contesting Native Title: From Controversy to Consensus in the Struggle over Indigenous Land Rights, Allen & Unwin, NSW, 2009.

- Ritter D, The Native Title Market, UWA Press, Crawley, WA, 2009

- Young S, The Trouble with Tradition: Native Title and Cultural Change, Federation Press, Annandale, NSW, 2008.

- Altman J & Hinkson M (eds.), Coercive Reconciliation: Stabilise, Normalise, Exit Aboriginal Australia, North Carlton, Victoria, Arena Publications, 2007.

- Langton M [et al.], Settling with Indigenous Peoples: Modern Treaty and Agreement-Making, Annandale, NSW, Federation Press, Annandale, NSW, 2006.

- Boer B & Wiffen G, Heritage Law in Australia, South Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Brennan S, Behrendt L, Strelein L & Williams G, Treaty, Federation Press, Annandale, NSW, 2005.

- Russell P H, Recognizing Aboriginal Title: The Mabo Case and Indigenous Resistance to English-Settler Colonialism, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2005.

- Langton M [et al.], Honour Among Nations? Treaties and Agreements with Indigenous Peoples, Carlton Victoria, Melbourne University Press, 2004.

- Reynolds, H, The Law of the Land, 3rd ed., Camberwell, Victoria, Penguin, 2003.

- Sutton, P, Native Title in Australia: An Ethnographic Perspective, Cambridge University Press, UK, 2003.

- Butt P, Eagleson R & Lane P, Mabo, Wik and Native Title, 4th ed., Federation Press, Leichhardt, NSW, 2001.

- Mantziaris C & Martin D, Native Title Corporations: A Legal and Anthropological Analysis, Federation Press, Annandale, NSW, 2000.

- Horrigan B & Young S, Commercial Implications of Native Title, Federation Press, Leichhardt, NSW, 1997.

- Hiley G (ed.), The Wik Case:, Issues and Implications, Butterworths, Sydney, 1997.

- Stephenson, M A (ed.), Mabo: The Native Title Legislation, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1995.

- Brennan, F, One land, One Nation: Mabo Towards 2000, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1995.

- Behrendt L, Aboriginal Dispute Resolution, Federation Press, Annandale, NSW, 1995.

- Essays on the Mabo Decision, University of Sydney Law Review, Law Book Company, Sydney, 1993.

- Bartlett R H & Meyers G D, Native Title Legislation in Australia, Centre for Commercial and Resources Law, University of Western Australia and Murdoch University, Western Australia, 1994.

- Stephenson, M A (ed), Mabo: A Judicial Revolution, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1993.

- Neate G, Aboriginal Land Rights Law in the Northern Territory, APCOL, Chippendale, NSW, 1989.

Also see:

- The Australian Indigenous Law Review, Indigenous Law Centre, University of New South Wales Sydney, NSW.

- Halsburys’ Laws of Australia, Butterworths, Sydney, 1991- , Volume 1, “Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders – Interests in Land” and “Aboriginal Heritage”.

- The Laws of Australia, Thomson Reuters, Melbourne, 1993-, Volume 1, “Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders”.

Useful Websites:

amuel Griffith, as first Chief Justice of the High Court, faced two difficulties. The first difficulty was the need to ensure that the High Court gained the respect of State Supreme Court judges. Some of them had opposed the creation of the High Court. They would have preferred that all appeals continued to go, as they had before 1903, straight from Supreme Courts to the Privy Council. In due course the Court, unlike Biblical prophets, did receive honour in its own country. The second difficulty was the need to ensure that the High Court gained the respect of the Privy Council, particularly in constitutional law. This it did, but only after exchanges of hostile fire between Sir Samuel and Lord Halsbury.

amuel Griffith, as first Chief Justice of the High Court, faced two difficulties. The first difficulty was the need to ensure that the High Court gained the respect of State Supreme Court judges. Some of them had opposed the creation of the High Court. They would have preferred that all appeals continued to go, as they had before 1903, straight from Supreme Courts to the Privy Council. In due course the Court, unlike Biblical prophets, did receive honour in its own country. The second difficulty was the need to ensure that the High Court gained the respect of the Privy Council, particularly in constitutional law. This it did, but only after exchanges of hostile fire between Sir Samuel and Lord Halsbury. The Central Theme

The Central Theme

May 1982

May 1982

The decision was attacked by some commentators as being a High Court “adventure”.

The decision was attacked by some commentators as being a High Court “adventure”. The Native Title Act 1993 was part of the Commonwealth Government’s response to the 1992 Mabo decision.

The Native Title Act 1993 was part of the Commonwealth Government’s response to the 1992 Mabo decision.

Then followed amendments in 2009 which provided that both the Court and the Tribunal may mediate in respect of an application and, also that another ‘appropriate person or body’ may mediate. The decision as to who should mediate was a matter for the Court.

Then followed amendments in 2009 which provided that both the Court and the Tribunal may mediate in respect of an application and, also that another ‘appropriate person or body’ may mediate. The decision as to who should mediate was a matter for the Court. Moving on to the mediation function for Federal Court proceedings:

Moving on to the mediation function for Federal Court proceedings:  The Tribunal may make recommendations in the report. However, any such recommendations are not binding between any of the parties to the inquiry (s163A)

The Tribunal may make recommendations in the report. However, any such recommendations are not binding between any of the parties to the inquiry (s163A) But see s 86(2)

But see s 86(2)