On 19 June 2014, James Cook University hosted a Reception for and CPD with the visiting Court of Appeal.  The evening was a most enjoyable way for the University to host the judges, local barristers and solicitors, students, academics and community groups — whilst also fostering its educative role.

Particularly impressive was the CPD. The Bar Association had arranged for a Sunshine Coast Barrister to fly up and speak about technology and advocacy. When that barrister missed his plane, the Northern Supreme Court Judge, Justice David North, did an outstanding job of addressing that topic on very short notice. The chair for the CPD, President Margaret McMurdo, and the commentator – Far Northern Judge, Justice Ken Henry- were also superb. It was an impressive display of the decency, reliability, knowledge and adaptability of the Bench — and a good night was had by all!

The speakers received a WWF Orangutan adoption, the book Tears in the Jungle (written by a disabled Australian boy, Daniel Clarke, about our need to care for orangutans) and a bottle of Veuve Clicquot — suitably orange in packaging!

The final CPD in the 2014 JCU-BAQ Series took place on Friday 27 June, when visiting Brisbane Barrister, Dr Max Spry, spoke about appealing stress claims in the industrial jurisdiction. As always, Dr Spry did a thorough and valuable presentation, for which JCU and the Townsville community are grateful.

Photograph from the Court of Appeal CPD and Reception:Â Justice Henry, President McMurdo, Justice North and Associate Professor Louise Floyd (the JCU host for the evening).

Associate Professor Louise Floyd

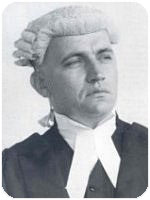

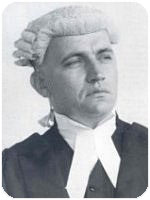

Frank Glynn Connolly was one of the great characters of the post-war Bar. Although he was not called until he was 33, he remained in practice for nearly six decades. In 1949 he was one of 70 practising barristers; today there are 900. Through these changes, he would remain, in the words of his old friend Sir Gerard Brennan, “true to his vision of the Bar as the defender of individual rights.” He was not only a well-known advocate but a devoted family man, a passionate poet, an abiding Catholic, and a popular colleague and confidant.

Francis (always Frank) was the elder son of Dr Francis Glynn Connolly and Mary Louise Earwaker; born at home at Wombah, in Racecourse Road, Hamilton on 23 January 1916. Frank’s great-grandfather, John Connolly, had emigrated from Ireland in 1842, settled in the Gayndah district and married Mary Glynn. He was educated at St Margaret’s Preparatory School, attached to St Augustine’s Church, next door. At eleven, he was already a performer — at the 3rd Annual Prize Distribution he played the Sandman, the Wolf, and sang ‘The Ti-Tree’. St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace followed.

At the University of Queensland, he was an inter-varsity debater and attained a BA with first class honours in English. In 1938 he went to England to write plays. On the boat he read the work of T S Eliot for the first time and poetry became a life-long passion. He met the great poet and shared some of his poetry with him. Eliot suggested he try prose first but, never defeated nor deflected, Frank continued to write for the rest of his life. As his daughter, Carolyn, recalled, he read deeply and had an extensive library but, for Frank, only two women could write — Jane Austen and Sappho — and a single Australian, Patrick White. Frank’s style was Tennysonian — romantic, idealistic, utterly uncontemporary, often inspired by myth – the Grail, Helen of Troy, Psyche and Cupid. His great aim was to give his poetry a musical quality and, though he never published his output, a friend of thirty years with whom he shared a love of the art, felt he achieved this.

Any observation on Frank’s facility for language must encompass his mastery of the expletive. Though not ‘in company’ (his much-loved wife found it neither clever nor funny) and never in Court, no one deployed the expletive with such polish, aplomb and profusion as Frank.

Frank returned to Brisbane after his health broke down just before the war. In January 1941 he enlisted in the Australian Army and served in coastal defence in New Guinea. When the British Army called for volunteers, he transferred to the Durham Light Infantry with whom he fought in India and Malaysia and attained the rank of Captain.

On 29 February 1942 at St Agatha’s Catholic Church, Clayfield, he married Mary Blair De Burgh Persse of Wyambyn, Beaudesert, after eloping — as her Anglican parents and his Catholic parents discussed whether they would be married in her family church or in his cathedral. During the war he wrote his MA thesis, on Eliot, ‘by the light of the moon’.

After the war Frank followed his father into medicine, but after a year’s study he switched to law, following his uncle, Hugh Glynn Connolly, of counsel and later a partner of Suthers Connolly, Townsville (subsequently Connolly, Suthers and Walker). Frank was called to the Bar on 15 February 1949, signing the roll just below his great friend and another memorable character of the criminal Bar, Colin Bennett.

Frank read, at first, in the chambers in the old Old Inns of Court in Adelaide Street of Rex King (later QC). It was King, Frank claimed, who taught him to swear. In response to a letter from Frank’s mother in May 1948 (promising not to tell Frank that she had written), Mr King wrote, “He has a most engaging and pleasing manner but lacks as yet something of maturity and self-reliance: these qualities I have no doubt will be added unto him and you may be sure that it will be my constant aim to aid nature and the effluxion of time in adding them. He talks well, is industrious and systematic in his work and possesses a genial enthusiasm which, with a little more maturity, should carry him a long way.” This enthusiasm never dimmed.

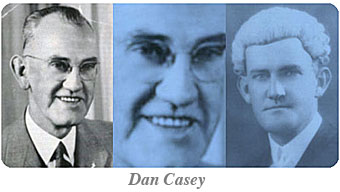

Every era makes legends of its predecessors but the Bar in the late forties and fifties had more than its share of characters. The outstanding criminal advocate of his time, Dan Casey, had chambers beside King’s. Octavius (Octy) North, (father of the Northern Judge and North, SC) was a colleague and friend; as were Kennedy Allen and Vince Fogarty. Ten months after Frank’s admission, his brilliant irascible cousin, Peter Connolly, was admitted to practice and his career was a source of pride for Frank. The Power family, a formidable legal dynasty in its time, were also cousins.

Frank refused, on religious grounds, to accept divorce briefs, which succoured most of the Junior Bar, but he appeared in maintenance actions. Frank must have been good copy throughout his career. The Courier-Mail‘s court reporter reported one exchange, “Wife to Mr F Connolly, barrister in Summons Court maintenance action, “I agreed to him sailing on these coastal vessels, but not to him having a girl in every port.”

Frank became a keen defence lawyer; most of his work was criminal. In an affectionate tribute on the fiftieth anniversary of Frank’s admission, James Crowley QC, recounted an early meeting between Dan Casey and Frank, seeking advice in advance of a trial. Casey advised that the first thing was to fully consider all the facts. Frank had done that. “Next, you must know the law thoroughly.” Frank had done that too. “Well if you’ve covered the facts and the law, how can I help you?” “Oh,” replied Frank, “I wanted you to fill me in on the bullshit.”

His practice also encompassed some civil work. For almost thirty years he appeared before the Medical Assessment Tribunal on behalf of the Medical Board. He was also often engaged as counsel in building disputes. But his real area of expertise was crime. Over the decades he represented men charged with rape and women suspected of murder; he defended thousands of Queenslanders from the Gold Coast’s Spiderman burglar to bottom-of-the-harbour’s Brian Maher. As an advocate, he was meticulous, exuberant, and persistent — to the exasperation of his opposing counsel and sometimes his judge. His turn of phrase appealed to juries. Defending Maher, he told the jury that the tax man had had a bad name since Palestine 2000 years ago and that tax evasion had become a national sport. A Crown witness “couldn’t lie straight in bed” and “couldn’t be believed if he sold ice creams in hell”. He had the gift of making his jury laugh. Yet they also grasped the passionate intensity of Frank’s belief in his client.

Frank would go to impressive lengths in pursuit of a defence. He once had a doctor friend take plaster casts of the offending, distended appendages of two clients charged with sexual assault to establish that the offence could not have been performed simultaneously. Frank took the casts in his case to Court, determined to tender them; only to be dissuaded by his fellow defence counsel.

All his geese were swans and often his interest and concern would not end at their sentencing. He proudly displayed on the walls of his chambers the art of one of his clients who had taken up painting in jail. One of Frank’s celebrated cases was R v Tonkin & Montgomery [1975] Qd R 1, in which he succeeded in having Karen Tonkin’s conviction for murder reduced to manslaughter on the basis of diminished responsibility. And, typically, he stayed in touch with her while she was in Wolston Park. “How is Kaaren?” he would always ask as officers the Public Defender returned from a visit. And his concern continued after her release.

Frank also developed a practice in the Northern Territory and was at least twice offered an appointment to the Supreme Court of the Territory but life on the bench was not for him.

His Faith was, with his family, central to his life. The family motto — En Dieu est tout — was so apposite. A regular worshipper at St Stephen’s Cathedral, he would often arrange for people in strife, referred to him by the clergy, to be granted public defence, or would otherwise have a solicitor friend brief him, with both doing the job pro bono.

The St Vincent de Paul Society, of which he was a dedicated member, was also a source of work he did gratis. He would make weekly lunch time visits to men in various boarding houses around the City, Valley and Spring Hill areas, where he would listen to their plight, arrange for the delivery of any household goods they might need and to hand out vouchers redeemable at a major chain store. On one occasion the store refused to provide tobacco and papers for a voucher — only food. A furious Frank sought out the manager and blasted him; finishing (minus a few expletives) with, “They might be poor but there’s no need to treat them poorly.”

In a letter to The Catholic Leader, defending his friend, John Bathersby, Catholic Archbishop of Brisbane, after some reactionary Churchmen complained to Rome about His Grace’s support for the Vatican II innovation – General Absolution, Frank exhibited not just his eloquence, his knowledge of history and love for his Church, but the importance of friendship. He wrote, “I am a Catholic. My mother was an Anglican as was my late beloved wife and I have seen intimately the splendid way of Christian life in that part of our divided Christian Church.” He ended his letter, “But above all, let us respect our pastor. We are blessed with an archbishop of great goodness and wisdom. He is the one endowed by the Spirit of God to be our guide. It is sad that he should be undermined by those in his care who, like unruly sons, rebel against the guidance of their father.”

Writing to an old friend a few weeks before his 80th birthday, Frank confessed, “Getting a bit slower but still fighting fit. I do a lot of Legal Aid work now – criminal cases. The law is becoming too complicated for the problems of this crazy age. Socrates the greatest Greek philosopher said the law can’t make people behave. It’s a moral problem – how to treat people decently.” And he finishes in characteristic style, “Well, you were always a man of few words. So I’d better stop now. Mary always told me, “You talk too much.” But I told her that was my profession.”

In January 2006, on the eve of his 90th birthday, he retired from criminal trials but for another eight years, he continued to care for his family, practice and defend his Faith, and polish his poetry.

His beloved wife Mary whom he nursed, then visited daily, through a long illness, died in 1995. His eldest daughter, Diana, whom he also cared for during her battle with motor neurone disease, died in 2008. He is survived by two daughters, Carolyn and Marina, and their children, who were with him when he died on 29 June.

Frank Glynn Connolly was a mighty man.

Mark McGinness

2 August 2014

[This is a revised version of the obituary that was published in The Courier-Mail on 1 August 2014 — Ed.]

SUMMARY

This article considers whether legal advice on the law of a foreign jurisdiction is privileged. This question is particularly pertinent to in-house counsel. The globalisation of commerce and the growth of multinational companies have seen an increase in the number of in-house counsel whose role may extend into jurisdictions in which they are not admitted. The Queensland Supreme Court was asked recently in Aquila Coal Pty Ltd v Bowen Central Coal Pty Ltd [2013] QSC 82 (hereafter Aquila Coal) to consider whether advice provided by a foreign lawyer on Queensland law was privileged in circumstances where the foreign lawyer was not admitted in Australia. The decision is significant because the court found, no doubt to the relief of many in-house counsel, that privilege can attach to such advice. This article discusses the decision in Aquila Coal, together with the broader privilege issues that it raises, and considers its implications for the in-house profession.

INTRODUCTION

The proliferation in recent decades of multinational companies has witnessed the growth in global businesses whose operations span many jurisdictions. Those businesses frequently have permanent in-house legal capabilities. Indeed, their in-house lawyers may themselves be based throughout a number of the jurisdictions in which the business operates. From time to time, those lawyers may be asked to advise on legal issues concerning a jurisdiction in which they have not been admitted to practice. Is such advice protected by privilege?

In Aquila Coal, the Supreme Court of Queensland had to consider whether privilege attached to legal advice provided by an in-house counsel who was advising on Queensland law but who had not been admitted in Queensland, or indeed in any other jurisdiction in Australia. Rather, the in-house counsel had been admitted in a foreign jurisdiction, namely New York. In short, the court found that privilege could attach to such advice.

This article discusses the decision in Aquila Coal and its implications. It does so by reference to the three situations in which the application of privilege may arise when foreign law is involved, namely:

(a) first, when a foreign lawyer advises on Australian law;

(b) second, when an Australian lawyer advises on foreign law; and

(c) third, when a foreign lawyer advises on foreign law.

The impact of the uniform evidence legislation on the application of privilege in these situations is also considered.

However, before discussing these issues, the test and rationale for the doctrine of legal professional privilege, together with the principles which have developed governing its application to in-house counsel, are revisited.

THE TEST AND RATIONALE FOR PRIVILEGE

It is well established that legal professional privilege is a substantive and fundamental common law right: Daniels Corp International Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2002)

213 CLR 5431. It allows a party to withhold the disclosure of communications which are properly the subject of a claim to privilege. The ability to withhold the disclosure of communications extends beyond adversarial proceedings and includes such matters as the ability to resist disclosure pursuant to a search warrant: Baker v Campbell (1983) 153 CLR 52.

The test of whether a communication or document is subject to legal professional privilege is whether the communication was made or the document was prepared for the dominant purpose of obtaining or providing legal advice (ie legal advice privilege) or to conduct or aid in the conduct of litigation in reasonable prospect (ie litigation privilege): Esso Australia Resources Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1999) 201 CLR 49 at [2] and [61] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron and Gummow JJ.

Barwick CJ in Grant v Downs (1976) 135 CLR 674 put it like this (at 677):

Having considered the decisions, the writings and the various aspects of the public interest which claim attention, I have come to the conclusion that the Court should state the relevant principle as follows: a document which was produced or brought into existence either with the dominant purpose of its author, or of the person or authority under whose direction, whether particular or general, it was produced or brought into existence, of using it or its contents in order to obtain legal advice or to conduct or aid in the conduct of litigation, at the time of its production in reasonable prospect, should be privileged and excluded from inspection.

The dominant purpose is a reference to the “ruling, prevailing, or most influential purpose”:

Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Spotless Services Ltd (1996) 186 CLR 404 at 416.

The underlying rationale for legal advice privilege is perhaps best explained in a frequently cited passage by Mason J, as his Honour then was, Stephen and Murphy JJ in Grant v Downs (at 685):

The rationale of this head of privilege, according to traditional doctrine is that it promotes the public interest because it assists and enhances the administration of justice by facilitating the representation of clients by legal advisers, the law being a complex and complicated discipline. This it does by keeping secret their communications, thereby inducing the client to retain the solicitor and seek his advice, and encouraging the client to make a full and frank disclosure of the relevant circumstances to the solicitor. The existence of the privilege reflects, to the extent to which it is accorded, the paramountcy of this public interest over a more general public interest, that which requires that in the interests of a fair trial litigation should be conducted on the footing that all relevant documentary evidence is available.

In terms of procedure, where a party makes a valid claim to privilege over a document, that document need not be disclosed2. Typically, claims to privilege are made in the list of documents provided to the other party during disclosure, which, depending on the rules, may need to be verified by affidavit or, if a claim to privilege is challenged, may then need to be verified by affidavit.3.

If a party remains unsatisfied with the other party’s claims to privilege it may bring an application seeking disclosure of those documents.4 In such an application, the onus of establishing that the documents are privileged lies with the party asserting privilege: Grant v Downs (at 689); see also AWB v Cole (No 5) [2006] FCA 1234 at [44](1). During the course of the application, the court may inspect the documents to determine whether they attract privilege. Indeed, the High Court has stated that courts have exercised this power too sparingly in the past: Grant v Downs (at 689). This can be achieved, in a practical sense, by handing a confidential folder containing the documents to the judge, but not to the party contesting the privilege claim.

Cross-examination may be permitted during the application in order to determine the dominant purpose for which a document was created: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2005] FCA 142 at [3]. Put another way, in determining whether a document was created for the dominant purpose of legal advice or anticipated litigation, it may be necessary to consider the state of mind of the person creating the document and to examine a number of diverse purposes and to balance them to resolve the question: Esso (at [73]).

Many of the cases dealing with privilege concern in-house counsel. This may be due to the special relationship that in-house counsel occupy. That is, an in-house counsel is both legal adviser and employee. For this reason, a significant amount of jurisprudence has developed addressing the position of in-house counsel.

THE POSITION OF IN-HOUSE COUNSEL

The starting point in any discussion on the application of privilege to in-house counsel is the High Court’s decision in Waterford v Commonwealth of Australia (1987) 163 CLR 54. That case concerned whether privilege attached to confidential communications between government agencies and their salaried legal officers that were undertaken for the purpose of seeking or giving legal advice.

In short, the High Court found that privilege could attach to such communications. Central to the court’s reasoning in Waterford were two factors: first, whether the salaried lawyers were independent of their employer, and secondly, whether the lawyers were competent. In upholding the privilege claim, Brennan J, as his Honour then was, stated (at 70):

If the purpose of the privilege is to be fulfilled, the legal adviser must be competent and independent. Competent, in order that the legal advice be sound and the conduct of litigation be efficient; independent, in order that the personal loyalties, duties or interests of the adviser should not influence the legal advice which he gives or the fairness of his conduct of litigation on behalf of his client. If a legal adviser is incompetent to advise or to conduct litigation or if he is unable to be professionally detached in giving advice or in conducting litigation, there is an unacceptable risk that the purpose for which privilege is granted will be subverted. As to competence, there is much to be said for the view that admission to practice as a barrister or solicitor is the sufficient and necessary condition for attracting the privilege, but the question was not argued and need not be decided.

Similarly, Mason J, as his Honour then was, and Wilson J stated (at 62):

Whether in any particular case the relationship is such as to give rise to the privilege will be a question of fact. It must be a professional relationship which secures to the advice an independent character notwithstanding the employment.

More recent decisions have developed these principles insofar as they apply to in-house counsel.

Thus, in Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd, Tamberlin J stated (at [4]-[5]):

The dominant purpose test has particular importance in relation to the position of in-house counsel because they may be in a closer relationship to the management than outside counsel and therefore more exposed to participation in commercial aspects of an enterprise. The courts recognise that being a lawyer employed by an enterprise does not of itself entail a level of independence. Each employment will depend on the way in which the position is structured and executed. For example, some enterprises may treat the in-house adviser as concerned solely in advising and dealing with legal problems. As a matter of commercial reality, however, both internal and external legal advisers will often be involved in expressing views and acting on commercial issues.

The authorities recognise that in order to attract privilege the legal adviser should have an appropriate degree of independence so as to ensure that the protection of legal professional privilege is not conferred too widely.

Thus, Tamberlin J was also concerned with determining whether the in-house counsel had “an appropriate degree of independence” before privilege could attach. It is clear from the above comments that Tamberlin J was also cognisant of the difficulties that can arise where an in-house counsel’s role may extend into commercial matters. In this regard, his Honour’s conclusion was significant (at [38]):

I am cognisant of the fact that there is no bright line separating the role of an employed legal counsel as a lawyer advising in-house and his participation in commercial decisions. In other words, it is often practically impossible to segregate commercial activities from purely “legal” functions. The two will often be intertwined and privilege should not be denied simply on the basis of some commercial involvement. In the present case, however, I am persuaded that [the in-house counsel] was actively engaged in the commercial decisions to such an extent that significant weight must be given to this participation. In many circumstances where in-house counsel are employed there will be considerable overlap between commercial participation and legal functions and opinions. As can be seen from the specific rulings below, I am not persuaded that in this proceeding [the in-house counsel] was acting in a legal context or role in relation to a number of the documents in respect of which privilege was claimed. Nor am I persuaded that the privilege claims were based on an independent and impartial legal appraisal.

Thus, Tamberlin J was of the opinion that the in-house counsel had crossed the rubicon and was not acting in a legal role in relation to a number of the documents over which privilege had been claimed. Each case, of course, turns on its own facts. For this reason, his Honour’s remark that “privilege should not be denied simply on the basis of some commercial involvement” is noteworthy.

In Telstra Corp Ltd v Minister for Communications, Information Technology and the Arts (No 2) [2007] FCA 1445, Graham J set out a test for when an in-house lawyer lacks the necessary measure of independence (at [35]-[36]):

In my opinion an in-house lawyer will lack the requisite measure of independence if his or her advice is at risk of being compromised by virtue of the nature of his employment relationship with his employer. On the other hand, if the personal loyalties, duties and interests of the in-house lawyer do not influence the professional legal advice which he gives, the requirement for independence will be satisfied.

In the case presently before the Court, there is no evidence, as I have earlier remarked, going to the independence of the internal legal advisers involved in the communications said to have been brought into existence for the dominant purpose of providing or receiving legal advice. There is nothing to indicate from the description of the six documents with which the Court is presently concerned that they must be documents for which privilege is properly claimed. Different considerations may apply if, say, the documents in question were opinions expressed by identified senior counsel where one might start off with the premise that by its nature the document would have privilege attaching to it. This is not such a case.

Thus, Graham J considered that the requirement for independence would be satisfied provided that the personal loyalties, duties and interests of an in-house lawyer do not influence the lawyer’s advice. Resolving this question, however, is not a straight forward matter for a court.

In Australian Hospital Care (Pindara) Pty Ltd v Duggan (No 2) [1999] VSC 131, Gillard J discussed the burden of proof in relation to a claim for privilege by an in-house counsel:

In my opinion once the client swears the affidavit of documents claiming legal professional privilege in a way which leads the court to the conclusion that the claim is properly made, then the prima facie position is that the legal adviser was acting independently at the relevant time.

It follows that if any other party to the litigation disputes the claim for legal professional privilege then it has the evidentiary burden of establishing facts which prima facie rebut the presumption.

…

If the party opposing the claim for privilege does establish facts which rebut the prima facie presumption then in the end result the party claiming the privilege must establish the propriety and validity of the claim.

The court may, after considering the issues, reach the conclusion that the lawyer was acting independently and accordingly the privilege is upheld, or that the lawyer was not acting independently and accordingly there is no privilege, or the court may reach a position where it is in doubt. If the latter stage is reached then the court should inspect the documents to determine the propriety and validity of the claim.

… the mere fact that the legal adviser is an employee of the client or that his duties may involve performing non-legal work do not establish that at the relevant time he was not acting independently. It is recognised that employees will perform non-legal work and it is an essential element of the establishment of the privilege that at the relevant time the employee was performing legal work. The fact of employment is relevant but the weight to be attached to that fact in considering independence will depend on all the circumstances.5

Thus, Gillard J considered that the fact of employment does not result in a lack of independence. Like Tamberlin J in Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd Gillard J also found that simply because the in-house counsel’s duties involve non-legal work does not mean that the in-house counsel’s legal work is not privileged.

However, legal advice privilege can only ever attach when legal advice is actually given or requested by an in-house counsel. With modern communications, in-house counsel are no doubt the recipients of emails that are sent to others within the business, but which are copied to the in-house counsel. Simply copying an email to an in-house counsel will not be sufficient to attract privilege unless that is done for the dominant purpose of seeking legal advice, or to conduct or aid in the conduct of actual or anticipated litigation. In this context, Katzmann J stated in Dye v Cth Securities Ltd (No 5) [2010] FCA 950 (at [50]):

The email appears to have been copied to [the in-house counsel] for the purpose of keeping him informed of the status of the applicant’s complaints and so that he was aware of what Mr Carroll was doing about them, not for the dominant purpose of seeking his legal advice or to conduct or aid in the conduct of litigation in reasonable prospect.

Nonetheless, the overriding principle remains that communications involving in-house counsel are capable of attracting privilege, provided the other requirements for a privilege claim are established. Put another way, whilst a court may look at the position of in-house counsel more closely, “there is no doubt that legal professional privilege may attach to communications with a lawyer who is a salaried employee”: GSA Industries (Aust) Pty Ltd v Constable [2002] 2 Qd R 146 per Holmes J (as her Honour then was) at [14].

How then do these principles operate when questions of foreign law are involved? It is worth noting at the outset that the principles discussed below apply equally to any legal advisers. However, it is likely that in-house counsel will encounter these issues more frequently than lawyers in private practice.

FIRST SITUATION: FOREIGN LAWYER ADVISING ON AUSTRALIAN LAW

Turning then to the first situation in which questions of foreign law may arise — when a foreign lawyer advises on Australian law.

This was the situation which confronted Boddice J in Aquila Coal. In that case, Aquila Coal had entered into a joint venture agreement with the defendant, Bowen Central Coal Pty Ltd (BCC), for the development of a proposed mine in central Queensland. The application before the court concerned Aquila Coal’s claim that certain documents over which BCC claimed privilege were not in fact privileged and should be disclosed.

A preliminary issue for determination was a submission by Aquila Coal that documents created by BCC’s in-house counsel were incapable of attracting privilege. This was because the in-house counsel had never been admitted as a lawyer in Australia. Instead, BCC’s in-house counsel had been admitted in a foreign jurisdiction, in this case New York. Thus, the question for the court was whether advice provided by a foreign lawyer on questions of Australian law could attract privilege.

Central to Aquila Coal’s argument was the Queensland Court of Appeal’s decision in Glengallan Investments Pty Ltd v Arthur Anderson [2002] 1 Qd R 233. In that case, the court was required to determine whether privilege could attach to advice provided by partners at Arthur Anderson who held law degrees, but were not admitted to practice. The Court of Appeal found that the advice was not privileged because privilege “can only attach where a lawyer admitted to practice is involved”: (at 245). However, the court was silent as to whether admission to practice in Australia was required, or whether it was sufficient to be admitted in a foreign jurisdiction.

In seeking to uphold its claim to privilege, BCC relied upon McLelland J’s decision in Ritz Hotel Ltd v Charles of the Ritz Ltd [No 4] (1987) 14 NSWLR 100. That case concerned a claim for privilege by an in-house counsel who was a member of the New York State Bar. In upholding the claim to privilege, McLelland J stated (at 101-102):

The author of the document, Mr Morrazzo, is a qualified lawyer and member of the Bar of the State of New York and the Federal District Court for the Southern and Eastern Districts of New York. He is an expert of trade mark law. He is employed by Revlon Inc, the parent company of the second defendant, in what is called its Law Department, which consists of a group of attorneys and their support staff, whose function is to provide legal advice and counsel to the management of Revlon Inc and its subsidiaries. …

I am satisfied that the sole purpose of the bringing into existence of this memorandum was to provide legal advice on these matters to Revlon Inc in connection with the proposed acquisition, that in doing so Mr Morrazzo was acting in his capacity as a professional legal adviser to the company, and that the memorandum was of a confidential nature.

It was submitted that because many of the trade marks were registered in foreign countries and that the litigation (or much of it) was in foreign courts, Mr Morrazzo was not competent to give legal advice in relation to such matters, notwithstanding his legal qualifications in the United States.

I do not consider that legal professional privilege is as limited as this submission would suggest. … it seems to me that legal professional privilege is not confined to legal advice concerning or based on the law of a particular jurisdiction in which the giver of the advice has his formal qualification. For instance, I have no doubt that legal advice by a lawyer qualified in New South Wales on matters involving the law of, for example, Victoria or the United Kingdom, would, in appropriate circumstances, attract legal professional privilege. Similarly, and particularly in a field with such international ramifications as trade mark law, I see no reason why legal advice from a lawyer qualified in New York, concerning trade marks and trade mark litigation in another country, would not, in appropriate circumstances attract legal professional privilege.

Whilst Charles of the Ritz was no doubt of assistance in seeking to uphold BCC’s claim to privilege, the ratio of that decision is not clear. Whilst it is clear that the in-house counsel in that case was qualified in New York, it is unclear from the judgment which country’s laws the in-house counsel was advising on. Further, the advice concerned trade mark law, a field with “international ramifications”. Does it make a difference if the advice concerns issues that do not have international ramifications?

Charles of the Ritz was referred to, without disapproval, by Holmes J (as her Honour then was), in GSA Industries (Aust) Pty Ltd. Again, that case concerned the position of in-house counsel. Her Honour’s comments are significant:

There is no amplification in the material submitted on behalf of the respondent as to what the position of legal counsel entails, and it is not asserted that Mr Moratti is admitted to practise as barrister or solicitor.

There is no doubt that legal professional privilege may attach to communications with a lawyer who is a salaried employee. The question was considered in The Attorney-General for the Northern Territory of Australia v Kearney and answered in the affirmative, at least in relation to government employees, in Waterford v The Commonwealth of Australia. In Ritz Hotel Ltd v Charles of the Ritz Ltd McLelland J concluded that a company employee who was a qualified lawyer and a member of the New York State Bar, was acting as a professional legal adviser whose communications were capable of attracting legal professional privilege. It is to be noted, however, that the lawyer in that case was admitted to practice, albeit in another jurisdiction.

…

Whether admission to practise be relevant to independence or to competence, it is clear, in this State at least, that privilege exists only in respect of legal advisers admitted as barrister or solicitor: Glengallan Investments Pty Ltd v Arthur Andersen. Having regard to that authority, and the absence of any evidence that Mr Moratti was an admitted practitioner, I conclude, inevitably, that his communications, whether involving legal advice or not, could not attract privilege as the communications of a legal practitioner.7

In Aquila Coal, Boddice J had to consider the application of the above principles to BCC’s claims to privilege. Usefully, his Honour summarised the position governing the application of privilege to in-house counsel as follows:

Where the legal advisers are employees of the party to the litigation, legal professional privilege may still attach, provided the claim relates to a qualified lawyer acting in the capacity of an independent professional legal adviser. Independence is crucial, as an important feature of inhouse lawyers is that at some point the chain of authority will result in a person who is not a lawyer holding authority, directly or indirectly, over the inhouse lawyer. The relevant question for consideration is whether the advice given is, in truth, independent.

In the case of inhouse lawyers, there is no presumption of a lack of independence.8

Thus, again, independence is critical and the court does not start with a presumption that an in-house counsel lacks independence. Ultimately, his Honour concluded that “the authorities relied upon by [Aquila Coal] do not support a finding that legal professional privilege cannot attach to the advice given by [BCC’s] inhouse lawyers or to the instructions provided to those inhouse lawyers, simply because [BCC’s] general counsel was not admitted as a legal practitioner in Australia”: (at [22]). The essence of his Honour’s reasoning is found in the following passages:

A conclusion that legal professional privilege can attach to the documents in question, notwithstanding that the defendant’s general counsel is not admitted as a legal practitioner in Australia, is consistent with the purpose of, and rationale behind, the doctrine of legal professional privilege.

Legal professional privilege is the privilege of the client, not the lawyers. It exists even where the client erroneously believed the legal adviser was entitled to give the advice. It would be contrary to the notion of the privilege being that of the client that the client should lose the privilege merely by reason that the legal adviser, who is admitted elsewhere, is not admitted in Australia.9

In reaching this finding, his Honour also dealt with a submission by Aquila Coal that (1) the restrictions on the in-house counsel practicing law contained in the Legal Profession Act 2007 (Qld) (the LPA) and (2) the in-house counsel’s lack of a practising certificate, both supported a conclusion that privilege should not apply. His Honour stated:

The provisions of the Legal Profession Act 2007 (Qld) (and their corresponding equivalents in the other jurisdictions in Australia) also do not support such a finding. That Act provides for the regulation of legal practitioners. It does not purport to regulate the availability of legal professional privilege. Further, the lack of a current practising certificate, whilst a very relevant factor in determining whether legal professional privilege exists in respect of advice given by inhouse legal representatives, is not determinative of the existence of privilege.10

Thus, his Honour did not consider the provisions of the LPA were relevant in determining whether privilege applied, nor was his Honour persuaded to reject the privilege claim by reason of the absence of a practising certificate. Putting this aside, it is nonetheless important for any lawyer to abide by the practising requirements contained in the LPA, given the potential ramifications for that lawyer of not doing so.

In summary, legal advice privilege can still attach to advice provided by a foreign lawyer on questions involving Australian law, provided that the foreign lawyer is admitted in a foreign jurisdiction and displays the necessary degree of independence from the business.11 Similarly, litigation privilege can also attach to documents created by that lawyer for the dominant purpose of conducting or in aid of litigation in Australia, again, provided that those same conditions apply.

What then of the converse situation? That is, where an in-house counsel admitted to practice in Australia advises on foreign law?

SECOND SITUATION: AUSTRALIAN LAWYER ADVISING ON FOREIGN LAW

The second situation in which questions of foreign law may arise is where an Australian lawyer advises on questions involving foreign law. It is this situation which is perhaps of most significance to in-house counsel who are admitted in Australia, but not admitted in the foreign jurisdiction.

Take the following example. A general counsel works in Australia for a British-based oil and gas company. The general counsel has been admitted in Australia, but not elsewhere. The general counsel reports to the global head of legal in London and is responsible for the legal function of the company’s operations in Australia, New Zealand and South East Asia. The general counsel advises on a contract governed by Singaporean law. Is such advice privileged?

Again, in order for privilege to apply, the necessary pre-conditions discussed above would need to be met. That is, the general counsel would need, at the least, to be admitted in Australia. The advice would also need to be confidential and provided by the general counsel acting in the capacity of an independent professional legal adviser. Beyond that, there does not appear to be any authorities concerning whether advice by an Australian lawyer on foreign law can attract privilege.

In principle, if the decision in Aquila Coal is followed, such advice may also be privileged. Applying his Honour Boddice J’s reasoning, such a finding would be consistent with the purpose of and rationale behind the doctrine of legal professional privilege. That is, it would be contrary to the doctrine of privilege that privilege should be lost merely by reason that the general counsel, whilst admitted in Australia, is not admitted in the foreign jurisdiction in respect of which the advice is given, namely Singapore.12

However, a respectable argument exists that such advice is not privileged. It is this. The in-house counsel’s employer must know, or, at the least, ought to know, that the in-house counsel is not admitted in Singapore. It is not a case of a lay client mistakenly believing that a solicitor was admitted to practice, in which case, privilege can still apply: see Grofam v ANZ (1993) 45 FCR 445. In Grofam, the Full Federal Court reached this view because “legal professional privilege is essentially concerned with the protection of the client” (at 456).

Turning then to the case at hand — why does an in-house counsel’s employer require any “protection” when it knows, or ought to know, that the in-house counsel is not admitted in Singapore? Put another way, what public interest exists in maintaining privilege in those circumstances? Indeed, is there even a relationship of lawyer and client upon which privilege could attach?

Perhaps the most that can be said is that, on the current state of the authorities, doubt exists as to whether privilege attaches to legal advice provided by an Australian lawyer on foreign law. Whilst the reasoning in Aquila Coal suggests that it does, that case did not decide this point.

For this reason, in-house counsel would no doubt take comfort from a decision in which the ability of privilege to apply in these circumstances is confirmed.

THIRD SITUATION: FOREIGN LAWYER ADVISING ON FOREIGN LAW

The third situation in which questions of foreign law may arise is where a foreign lawyer advises on questions involving foreign law. Changing the above factual scenario slightly, the British oil and gas company again requires advice on a contract which is governed by Singaporean law. Instead of providing the advice in-house, the general counsel engages a Singaporean law firm to provide the advice on Singaporean law. Is such advice privileged from disclosure in proceedings brought in Australia?

This question came before the Full Federal Court in Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185. In obiter, Allsop J (as his Honour then was) discussed whether privilege could apply in this situation. His Honour started by considering the reality of modern commercial life in which the assistance of foreign lawyers may be necessary:

Members of the community may well need to seek the assistance of foreign lawyers. The considerations of the kind that Wilson J spoke of in Baker v Campbell: the multiplicity and complexity of the demands of the modern state on its citizens, the complexity of modern commercial life and the increasing global interrelationships of legal systems, commerce and human intercourse, make treatment of the privilege as a jurisdictionally specific right, in my view, both impractical and contrary to the underlying purpose of the intended protection in a modern society.13

Thus, given the realities of the modern world, his Honour considered that privilege should not be restricted to advice on local law. Put another way, Allsop J considered that privilege should not be a “jurisdictionally specific right”. In upholding the claim to privilege, Allsop J also relied on the rationale underpinning the privilege doctrine:

A refusal to recognise foreign lawyer’s advice privilege or narrowly to constrict advice privilege to the precise communication requesting or imparting the advice … would undermine the rationale of the privilege. It would also undermine the administration of justice by enlivening a threat in this jurisdiction to the confidentiality of communications which would otherwise be protected in other places.

…

The above conclusion as to the place of foreign lawyers undermines, from a legal perspective, any view which may be taken to have been expressed by the primary judge that the claim for privilege must fail for lack of connection between the advice and the administration of justice in Australia because it was advice of a foreign lawyer.14

In short, his Honour considered there was “no basis for viewing foreign lawyers and foreign legal advisers differently to Australian lawyers and legal advice”.15

Interestingly, his Honour left open the question of whether advice on foreign law by a foreign lawyer could be privileged in Australia in circumstances in which the advice was not privileged under the foreign law. His Honour stated:

Also, nothing I have said should be taken as expressing a view on the existence of privilege in Australia where, under the legal system governing the foreign lawyer, or under the legal system of the state where the advice was given, no privilege would attach.16

In summary, if Allsop J’s remarks find support elsewhere,17 there is nothing to prevent advice on foreign law by a foreign lawyer from attracting privilege.

THE IMPACT OF THE UNIFORM EVIDENCE ACT REGIME

The common law position, as set out above, has been modified somewhat in the jurisdictions in which the uniform evidence legislation applies. For convenience, the provisions of the Commonwealth Act, the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act) are referred to below.

The Evidence Amendment Act 2008 (Cth) made a number of changes to the Evidence Act, including changes with respect to the application of privilege. These changes implemented the majority of recommendations made in a joint report published by the Australian, NSW and Victorian Law Reform Commissions in February 2006.

Under s 118 of the Evidence Act, privilege can attach to a confidential communication between a client and a “lawyer”. The 2008 amendments extended the definition of “lawyer” to include foreign lawyers. In particular, a “lawyer” now includes “Australian registered foreign lawyers” and “overseas registered foreign lawyers”: s 117. An “Australian registered foreign lawyer” is a person registered as a foreign lawyer under the law of one of the States or Territories.18 An “overseas registered foreign lawyer” is a natural person who is properly registered to engage in legal practice in a foreign country by an entity that has that function.19 Thus, by these amendments the definition of lawyer includes anyone that is properly registered in a foreign country as a lawyer.

Noticeably, however, the Act is silent as to whether privilege attaches to advice provided by a lawyer on the law of a jurisdiction other than the one in which they are admitted to practice.

Relevantly, the Explanatory Memorandum introducing the new definition of lawyer stated:20

This item also extends the definition of “lawyer” so that it includes a person who is admitted in a foreign jurisdiction. The rationale of client legal privilege to serve the public interest in the administration of justice and its status as a substantive right means it should not be limited to advice obtained only from Australian lawyers. This position reflects the reasoning of the Full Federal Court in Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185.

Thus, privilege should not be restricted to advice from Australian lawyers. As the Explanatory Memorandum notes, the amendments are said to reflect the common law position in Kennedy v Wallace. Kennedy v Wallace, however, only dealt with the third situation identified above, that is, where a foreign lawyer advises on foreign law. Thus, s 118 confirms that such advice is privileged. However, Kennedy v Wallace was not concerned with the first or second situations identified above, that is, where a foreign lawyer advises on Australian law, or an Australian lawyer advises on foreign law. For that reason, the amendments do not seem to have any application to these two situations. The common law, as discussed earlier, still applies. The amendments only impact upon the third situation (ie. foreign lawyer advising on foreign law) and simply reflect the position at common law. Thus, in summary, the expanded definition of “lawyer” in the Evidence Act does not seem to have changed the common law position that applies in any of the three situations discussed earlier.

Further, it is worth noting that the Evidence Act only applies to privilege claims at trial, and to certain interlocutory processes or document requests pursuant to a court order.21 The Evidence Act has no application to non-curial proceedings.

Before concluding, s 119 of the Evidence Act also requires comment. That section is headed “Litigation” and establishes a statutory test for claiming litigation privilege.22 It extends privilege to confidential communications between a lawyer and a client made for the dominant purpose of providing “professional legal services” with respect to actual, anticipated or pending proceedings in Australia or in an overseas court. Privilege also attaches to confidential communications between a lawyer and another person, as well as the contents of a confidential document, provided the communication was made, or the document was prepared, for that same dominant purpose. In order for the privilege to apply, it is also necessary that the client “is or may be, or was or might have been” a party to the Australian or overseas proceedings.

The same expanded definition of “lawyer” as set out above applies. Thus, communications with foreign lawyers acting for clients in proceedings before an overseas court can attract privilege. In particular, the provision of “professional legal services” to such a client is privileged if that was the dominant purpose of the communication. “Professional legal services” is not defined in the legislation. Odgers23 takes the view that a document prepared for use in such proceedings will be privileged.24

Thus, in short, the effect of the expanded definition of “lawyer” seems to be this. Privilege may be claimed over communications with foreign lawyers with respect to actual, anticipated or pending proceedings in foreign courts provided that the dominant purpose of the communication was for the provision of “professional legal services”. Similarly, privilege may be claimed over documents prepared for use in such proceedings, again provided that that same dominant purpose is present. In this manner, s 119 provides statutory recognition of litigation privilege to communications with foreign lawyers in relation to foreign proceedings. No doubt this is welcome news for multinational companies who may be involved in a number of cross-border disputes at any one time.

CONCLUSION

The decision in Aquila Coal represents a significant win for the in-house profession. It confirms that advice on Australian law provided by a lawyer admitted in a foreign jurisdiction can attract privilege. That is, privilege can still attach to the advice even though the foreign lawyer was not admitted in Australia.

In Aquila Coal, the court grounded its decision by looking to the purpose of, and rationale behind, the doctrine of privilege. The court reasoned that it would be contrary to the notion of privilege that privilege could be lost by reason of the lawyer being admitted elsewhere, but not in Australia. Adopting that same analysis, advice on foreign law by lawyers admitted in Australia may also attract privilege – provided, of course, that the other requirements for a privilege claim are met. However, as outlined above, there is a respectable argument to the contrary. The amendment to the definition of “lawyer” in the Evidence Act does not seem to have changed the position at common law. Thus, judicial confirmation that privilege can apply to advice on foreign law would no doubt be welcome news for multinational companies and their in-house counsel.

Dan Butler

Barrister at Law, Gerard Brennan Chambers

I am grateful to Chris Crawford for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

This article has been reproduced with the kind permission of Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia Limited (www.thomsonreuters.com.au). This article was first published in February 2014 by Thomson Reuters in the Australian Business Law Review and should be cited as In house counsel advising on foreign law: is it privileged,? Butler, (2014) 42 ABLR 5. For all subscription inquiries please phone from Australia: 1300 304 195, from Overseas +61 2 8587 7980 or online at www.thomsonreuters.com.au/catalogue. The official PDF version of this article can also be purchased separately from Thomson Reuters.

This publication is copyright. Other than for the purposes of and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act (Australia) 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia Limited, PO Box 3502, Rozelle, NSW, 2039 or online.

- At [9], [11], [44] and [132].

- See eg, r 212 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld); r 21.5 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW).

- See r 213 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld); r 21.4 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW); r 29.04 of the Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 2005 (Vic) and r 20.17 of the Federal Court Rules (Cth). Some rules provide that the affidavit must be made by a person who knows the facts giving rise to the claim: see r 213 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld); r 29.10 of the Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 2005 (Vic).

- See eg. R 223 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld).

- Australian Hospital Care (Pindora) Pty Ltd v Duggan (No 2) [1999] VSC 131 at [67], [68], [70], [71], [81] and [82]. Relied upon by Boddice J in Aquila Coal Pty Ltd v Bowen Central Coal Pty Ltd [2013] QSC 82 at [9].

- Aquila Coal Pty Ltd v Bowen Central Coal Pty Ltd [2013] QSC 82 at [1].

- GSA Industries (Aust) Pty Ltd v Constable [2002] 2 Qd R 146 at [13], [14] and [17].

- Aquila Coal Pty Ltd v Bowen Central Pty Ltd [2013] QSC 82 at [8] and [9].

- Aquila Coal Pty Ltd v Bowen Central Pty Ltd [2013] QSC 82 at [24] and [25].

- Aquila Coal Pty Ltd v Bowen Central Pty Ltd [2013] QSC 82 at [23].

- See also Great Atlantic Insurance Co v Home Insurance Co [1981] 1 WLR 529 at 536 (Templeman LJ); referred to in Grofam v ANZ (1993) 45 FCR 445 at 455.

- Aquila Coal Pty Ltd v Bowen Central Pty Ltd [2013] QSC 82 at [25].

- Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185 at [200].

- Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185 at [202] and [216].

- Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185 at [207].

- Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185 at [214].

- See Australian Crime Commission v Stewart [2012] FCA 29, upheld on appeal: Stewart v Australian Crime Commission (2012) 206 FCR 347.

- See the definition in the Dictionary and reg 10 of the Evidence Regulations 1995 (Cth).

- See the definition in the Dictionary.

- Explanatory Memorandum to the Evidence Amendment Bill 2008 at [174].

- See Esso v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1999) 201 CLR 49 and s 131 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

- Although the section can also extend to legal advice: see Odgers S, Uniform Evidence Law (100th ed, Thomson Reuters, 2012) at [1.3.10720].

- Odgers, n 22 at [1.3.10720].

- Relying upon Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1998) 81 FCR 526.

I had seen the 2002 movie based on the book when it had come out.

But Greene’s novels I had, for some unfathomable reason, allowed to pass me by.

Greene was one of my parents’ favourite authors, along with AJ Cronin, Somerset Maugham and John Steinbeck. But, until two years ago, I had failed to read a single Greene novel. One wonders why. They are short, easy to read, beautifully written and on subjects that grab my attention. There has been, in recent times, a Graham Greene reading rush among my spouse and at least two of my children. But there it is. I have failed to get aboard.

After my famous trip to Mexico for Seb and Beca’s wedding, my chamber colleague, Robbie, lent me his copy of The Power and the Glory, a novel about an alcoholic priest in the free and sovereign state of Tabasco in the 1930s when being a priest in Tabasco was not good for one’s longevity. That was my introduction to the Greene novel. It should have been enough to have me attacking the whole anthology.

The Quiet American is set in Saigon, post General Lattre and prior to Dien Bien Phu, perhaps, 1952. It commences at its conclusion and is, accordingly, told in retrospect by its British journalist narrator, Fowler.

The Quiet American is a love triangle taking place against the background of a vicious and complicated war. Fowler’s woman, Phuong, which means Phoenix, leaves him for Alden Pyle, the eponymous quiet American. This is happening, however, amid a strange and accidental friendship between the two men: Fowler, the “reporter” who withholds judgement and refuses to commit to position or side and Pyle, the innocent ideologue, who means good to all but blunders into creating a savage mayhem.

Zadie Smith calls the set of relationships a shady triad. Ms. Smith points out that the three characters’ contrasting lives and personalities are balanced, one against another, such that the reader never feels comfortable to make a final judgement upon, or in favour of, any one of the three characters.

I stumbled upon Zadie Smith’s excellent essay on Greene and The Quiet American. My friend, A., and I often chat in a coffee line or a lift. We seldom chat about books. It was an inspired idea then for A. to ask me what I was reading when I was still only half way through The Quiet American. I told him. He had finished it a few days earlier and it was A. who recommended Ms. Smith’s essay which was the introduction to the edition of the book he was reading.

Ms. Smith emphasises the subtle lines which are used to portray the characters in a Greene novel. She compares Greene’s work to that of Henry James, apparently, a favourite author of Greene’s childhood. Certainly, the reader of The Quiet American cannot trust Fowler’s descriptions of himself. Throughout the novel, Fowler describes himself as a reporter, not a leader writer. He does not take sides. He does not commit to ideas or people. Though eschewing cynicism, he is a reporter who simply calls the action as it happens, without blame or justification.

If the novel is the chronicling of a finding of commitment by Fowler, the reader is no less convinced of the innocence (or quietness) of Pyle by the end of the novel. Is Fowler one who not only fails to know himself but one who gets it wrong even when he is simply calling the action? The unreliable narrator places the novelist and reader at worse than arms’ length. No judgement can be trusted and the reader is left still puzzling, weeks and months after the final page is turned and read.

Perhaps, Ms. Smith’s most useful insight concerns the journalistic style with which Greene relates his novels. Critics should stop denying the journalistic nature of Greene’s novels, she says, but, rather, claim him as the greatest journalist of all time.

I am drawn to Greene’s turn of phrase. I fall in love with the quotable sentences that permeate the book and are capable of turning up in quotation books everywhere.

The innocence thesis is set out early in the book. Pyle is innocent but Fowler, as narrator, is aware of the dangers that innocence brings: “It never occurred to me that there was greater need to protect myself. Innocence always calls mutely for protection when we would be so much wiser to guard ourselves against it: innocence is like a dumb leper who has lost his bell, wandering the world, meaning no harm”.

And on time and revenge: “Time has its revenges, but revenges seem so often sour. Wouldn’t we all do better not trying to understand, accepting the fact that no human being will ever understand another, not a wife a husband, a lover a mistress, nor a parent a child?” What chance does a reader have on that premise?

Zadie Smith said that, reading the novel again, she was made conscious of all the Pyles of the world and the dangers they pose and the evil they do.

Though I grew up in confronting the Vietnam War, I felt I obtained a better understanding of that (later) conflict and the country, itself, from The Quiet American than I did from any of my reading of the time.

If, like me, Greene somehow slipped past you, rectify that wrong next chance you get. If you are an old friend, re-visit the pages of this novel, at least. Among all the subtleties and uncertainties of characters and morality, we take plenty away from Mr. Greene’s writing. Maybe, he is, indeed, the great journalist.

Almost uniformly, the Blokes loved The Quirt American. Maybe, they, also, had inherited their appreciation from their parents. And we endured the four point loss in the football game. Maybe, we had learned that life is complex and winning streaks that extend to nine cannot be expected.

One more happy phrase to carry with you through the day: “There was starlight, but no moonlight. Moonlight reminds me of a mortuary and the cold wash of an unshaded globe over a marble slab, but starlight is alive and never still, it is almost as if someone in those vast spaces is trying to communicate a message of good will, for even the names of stars are friendly.”

Even when your team loses.

Stephen Keim

Alternative Dispute Resolution

Another relatively modern trend is alternative dispute resolution. What do you think about that?

Well, if you look at fundamentals, the first point about it was that settlements occurred in my day between barristers opposing each other. They would settle on the Court steps, or the steps of the Inns of Court, and they’d know what should be settled and they would then settle it. You’d have the solicitors preparing a brief – that was their function – and you’d have the barristers prepared to argue the case in Court. Then, when it was properly prepared, proper thought could be given to settling it.

Now what did you have in place of that? What you have are solicitors who as soon they get the case, you know, they work for the case to be mediated right from the start. This is before they’ve looked at it properly and discovered whether there are any points that are difficult or anything of that sort or before they get an opinion from anybody. Indeed, the practice of getting counsel’s opinion seemed in my last years at the Bar to be terminally ill.

I just don’t think the solicitors are doing their job and, with mediations, they are being given a very attractive way of getting out of doing their job properly, of doing the hard work.

They say, for example, “Well, this is a personal injury matter and the fellow has lost his leg and he should get $50,000” or whatever it happens to be. That’s just off the top of the solicitor’s head. That’s what they’re going to go for and then somebody or other becomes the mediator. So the solicitor gets there for the mediation. He doesn’t know if there are all necessary proofs from the client. He has some reports from doctors. He has a bit of stuff. He also probably has several case files full of things like the fellow’s bank statements years before he had the accident. Completely irrelevant stuff, but he thinks it all needs to be briefed to the barrister because if he doesn’t he thinks he might be sued for negligence. Well, you know the thinking; someone might find it relevant so I better send it up. Anyway, I can copy it all and that justifies part of my fees.

The mediator, he mightn’t be much better briefed than the barristers are, and he’s got a range that goes from, say, $10,000 to $60,000. So he gets some sort of figure and he says, “Well, I think that would be a good figure”.

Now what’s happened of course is that you will find there’s been a breach of ethics by the solicitor because he hasn’t really tried to get the best figure for his client. He doesn’t really know what the best figure is and that is because he hasn’t prepared the case anywhere near enough to know any better.

Then if the solicitor is a bit crooked, he just goes one stage further than what I’m talking about and he says, “Well, I reckon my costs in this are $50,000” or whatever it is. Some figure just jumps out of the air. So he says to himself, “I need to get that from the settlement”. So once he gets to that figure in the mediation, he’s happy. He is then in conflict with his client. He wants the client to accept the offer because his fees will be squared away. So, the primary motivation for the mediation has become an exercise in getting the solicitor paid rather than compensation for his client.

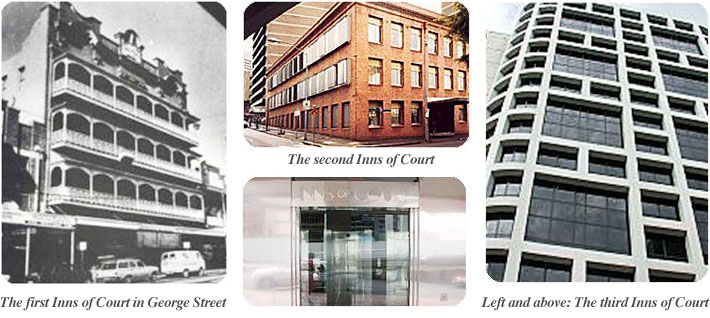

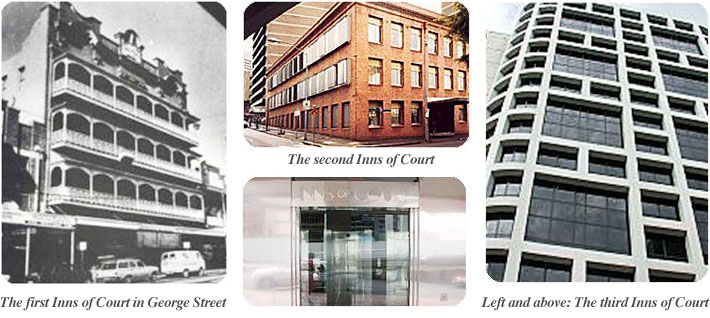

Construction of the Inns of Court

Amongst your achievements as President was the instrumental role you played in the construction of the Inns of Court. Persuading so many barristers to agree on that proposal must count as one of your greatest feats of advocacy?

Amongst your achievements as President was the instrumental role you played in the construction of the Inns of Court. Persuading so many barristers to agree on that proposal must count as one of your greatest feats of advocacy?

Well, I don’t think there were too many speeches about it. There were a couple of meetings but I think that it was probably a question of getting the building going. We had a couple of meetings, trying to get with SGIO, in fact, some development up and running. It didn’t succeed but there were discussions at that stage and I reckon there was a very small majority in favour of doing something.

We then went to a stage where we had to consider what we were going to do quite seriously and it was at that stage, I think, that it got going. We put together a book which showed you pictures of how it would be and so forth and the documents you’re going to sign for shares, different figures showing what would happen with that and so on.

And we then had a system of trying to get people individually to come along and have a talk and show them these things. So we slipped on then, I reckon, to the next level where we had about 70% in favour of it.

Some of the opposition was quite ridiculous. For example, one senior junior was a member of the Irish Club. He’d go down there quiet often to drink and as a result, he got this strange view that he was some sort of property expert. He said, based on what he thought the Irish Club was worth, that our site was worth at least $10 million. Well while you couldn’t get him to change his mind on that, the views he expressed caused a lot of people to say, “Look that’s a bit ridiculous”. So we found that our support got higher as a result of the stance he took and, in the end, we got about 90% in favour.

Then the important thing was to show that we were doing something. At the Bar there is always talk about what we’ll do, but not much action. We’re great men for the defendant. We can find reasons why it mightn’t work; you know, the sky might fall in, all sorts of things can happen. But we overcame all of that and got moving with it.

The only unfortunate thing about the whole business was that we never got enough people to go into the building next door. We could have bought that for something like $300,000, it was a real steal. But we’d expended all our energy. So we never went ahead unfortunately. If we had about a year or so living in the new building, we probably could have got that one too.

The statue, “Advocacy”, that we see in the foyer of the Inns was sculpted by Mrs Hampson. What was the story behind that?

The statue, “Advocacy”, that we see in the foyer of the Inns was sculpted by Mrs Hampson. What was the story behind that?

I think it was just an idea that I introduced to the directors that we should have something significant. There was a philosophy that was around at that stage that every new building had to spend a percentage of its total cost on artworks.

So I thought the best idea really would be if we got a statue made. And, of course, the directors didn’t know much about that so I said, “Look, I’ll get my wife to make a model. You can see what I’ve got in mind”. They agreed, and Catharina produced a model. The directors liked the model and what you see in the foyer is the result.

The statue is of a barrister, a man, a woman and a child. Is the barrister you?

The statue is of a barrister, a man, a woman and a child. Is the barrister you?

At the time, I didn’t think it was intended by Catharina to be anybody to be honest. More recently, she disclosed that the barrister’s head was inspired by a wax-bronze bust she made of me prior to the making of ‘Advocacy’. I was completely unaware of that until then. Apparently, certain changes were made by Catharina to avoid the possibility of an exact likeness to me and she also said that the woman and child were inspired by the writings of Patrick White.

It conveys a wonderful impression of a barrister — someone who is helping others?

Yes. That’s right. I think it says a lot.

Before we leave the topic of the Inns of Court, it would be remiss of me not to seek your help to solve a mystery. After entering the lift on the ground floor of the Inns, one finds that you travel very quickly to Level 5. The reason of course is that Levels, 1, 2, 3 and 4 seem to have vanished. Can you shed any light on that?

They certainly got lost at some point, but I don’t know how they got lost. I think it was something inspired by the builders. They also had a theory that was current at the time that you shouldn’t have a Level 13 in the building either. And I said, “Won’t that be funny though?” But they didn’t think it was funny at all.

One of the theories that abounds is that, by starting the floor count at 5 instead of 1, the Inns would end up having a higher numbered top floor than the building which then housed the Bar in Sydney. In that way, so the theory goes, the Inns would be seen to be one floor higher. Could that be correct?

It might have had that effect but it wasn’t conscious. I can remember people talking about it at the time, but that’s about all. The builders gave us the floors and we just took them.

Preparation

How did you prepare for a case?

Well, these are counsels of perfection, but what I tried to do was to know every fact there was about the case. I’d know every word that was ever written or spoken about the case that could be relevant because you never knew what would come up.

For instance, in a motor vehicle accident personal injuries case, there might have been a trial in the Magistrates Court for the driver of the car for driving without due care and attention. If so, I would want to summons the record and read every word of it. Sometimes you’d read the record and there’d be something that you’d find that was quite important. So you’d, in effect, try to find out everything that was connected to the case.

Then in the process of doing that reading, I would write down all the facts. I used to have a system of exercise books, and I’d start off on a page and I’d write down what I thought the facts were.

To continue the personal injuries case example, I would start off with the plaintiff born on such and such a day, where he went to school, his work experience, history, when he got married and all that sort of thing right up until the date of the accident. Then he’s in hospital and this happened to him or whatever. So the idea was that you ended up with a timeline of the whole thing.

In the same way, I would put down how the accident happened. He was driving a car this night or whatever it was, the whole sequence of the accident – relying on this statement and the statements of other witnesses and so forth. You’d put all that down.

And very often the tabulation of all those facts would be very revealing because they’d tell you something that wasn’t there. And you could go and search for that and get that right. Then you had a feeling that you had all the facts on his life along with all the facts on the accident.

If there was some other thing that was important it needed to be dealt with. Supposing that the big thing in the case was that he was expected to get a promotion. If so, you might make that a little story in itself.

The only other thing was that, as you read the statements of each witness, you’d write out in some convenient place any important things to get from him. For example, his statement might have been silent as to whether the lights were on, or not, so you’d put that down and get that during your conference with that witness.

When you had all those things together, and patched up all the holes which were in the account of them, you were probably ready to run from the factual side of things.

What you are describing is of course simply hard work?

Oh yes, it’s a lot of hard work. There’s no doubt about it. It takes a long time to prepare something properly.

But you have to remember there has to be a limit to this because you would keep going and going and going and end up with more manila folders than you could possibly cope with. So at some stage you’ve got to say, “Well, that’s enough, I’ve answered the question.” I’m not going to ask the solicitor to get in touch with the police in Perth to see whether when he was living there for two years or something, unless it’s a terribly important point. So there’s a question of judgment to be exercised as well. You have to know when enough is enough.

Work and Life

Because good preparation is a function of hard work, I expect you worked many long hours over your career?

Because good preparation is a function of hard work, I expect you worked many long hours over your career?

Yes. Quite long hours. And you never really catch up. A good example of that was one Easter. I decided I’d catch up. I had opinions and various things I hadn’t done. I said to Catharina, “Well, you do something with the kids over Easter because I’m going to work every day”. So that gave me five days to catch up. And I worked damn hard.

I got in at chambers at six o’clock and came home about ten at night and got it all done. I was really pleased and thought that it was a very good exercise. During the next week the opinions or whatever I had done were typed up and sent out. However I found that within a fortnight I was as far behind as I was before I started at Easter. So that’s paperwork – it’s just something you could never really ever get on top of.

Did you work much at home?

I would always try to be home in time for dinner with the family. But then I would always go away and read things like transcripts and all that sort of stuff at home. Mainly reading.

You always seem to be involved in many other things outside the law. Is it important to a barrister to have outside interests?

Well, I think its desirable. A fellow who didn’t have many outside interests was Arnold Bennett. He was interested in his profession and that was about all. He was pretty light on the other side and I think – I hesitate to use the word — but I think it probably makes you less happy. You don’t have a full enough grasp on the world to be happy about it. I think that’s what happens.

Do you think leading a more rounded life might make you a better barrister?