To most lawyers, Samuel Griffith is the jurist who drafted the Constitution, the Criminal Code, and many other laws, and who became Australia’s first Chief Justice.

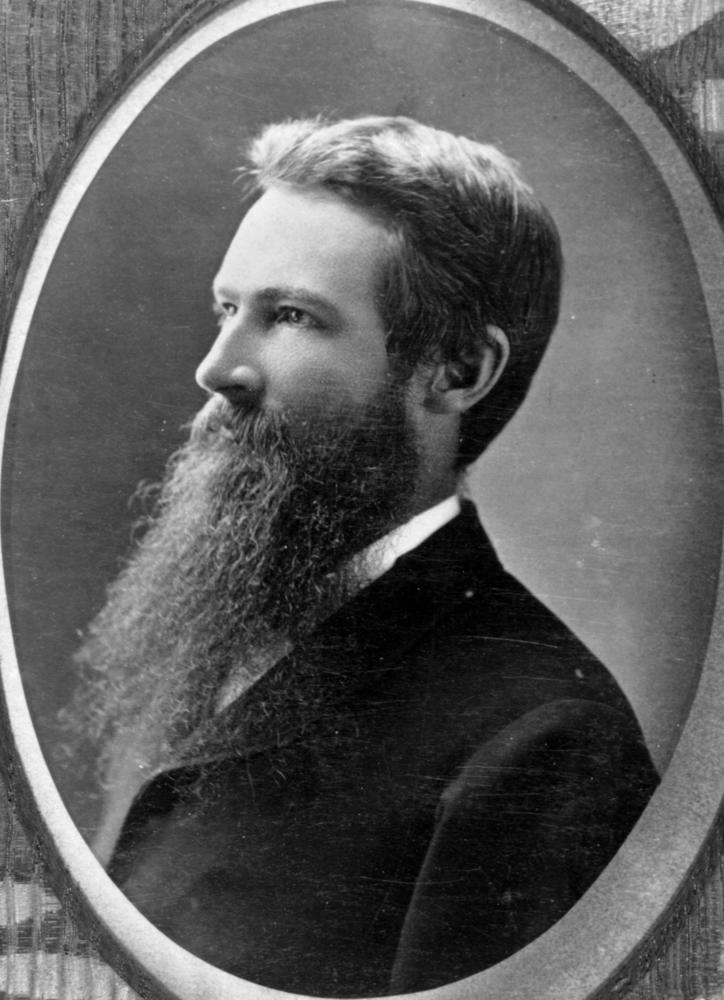

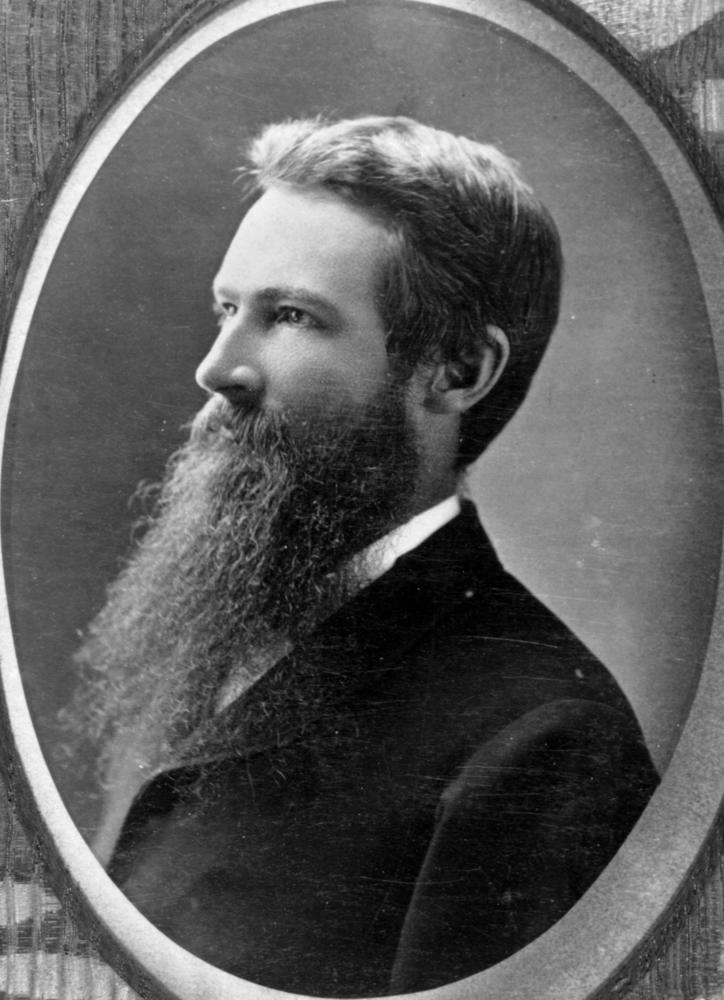

Portraits and photos of Chief Justice Griffith show a grey-bearded, austere figure.

Earlier in his life, Griffith was many things: a precociously gifted student who went down from the bush to top Sydney University aged 17; a brilliant legal practitioner from the age of 18 with an unmatched work ethic; an idealistic, young, progressive MP who opposed vested interests and crusaded against the kidnapping of Melanesians to work on Queensland plantations; and a more mature politician who, at the end of the his career, went into coalition with the conservative interests that he had earlier tormented.[1]

Griffith was not always a grey, old man. In middle age, he was passionate, bright eyed, and sported a bushy black beard.

In 2020, 100 years after Griffith died, a webinar hosted by the Australian Academy of Law and the Supreme Court Queensland Library touched upon some aspects of Griffith’s remarkable life. One of the speakers was the distinguished historian, Dr Raymond Evans, who spoke about Griffith’s Welsh origins.

As a young historian in Queensland in the mid-1960s, Raymond Evans began researching and writing about violence on Queensland’s frontier. Around the same time, another young historian, Henry Reynolds, was doing the same in North Queensland. Each pioneered writing and teaching in an area that had been ignored by universities, the media, and most of the public.

In 1975, Evans co-authored with Kay Saunders and Kathryn Cronin the ground breaking book Race Relations in Colonial Queensland: a history of exclusion, exploitation and extermination. His publications include A History of Queensland (Cambridge University Press). Decades after he started his historical research, Raymond Evans contributes to prestigious international works about genocide in Northern Australia.[2]

In 2021 and 2022, Henry Reynolds, in a book and then in Griffith Review, accused Samuel Griffith of having prime responsibility for violence on the Queensland frontier during the time Griffith held office. In one flourish, Reynolds wrote that Griffith’s “neatly manicured lawyers’ (sic) hands were deeply stained with the blood of murdered men, women and children”.

These claims came as a surprise to Raymond Evans, who, while not a cheerleader for Griffith, had never seen Griffith as at the forefront of frontier violence by the Native Police or of having condoned it. Independently, other historians questioned whether Griffith was a suitable candidate for posthumous indictment for the crime of genocide.[3]

His curiosity aroused, Raymond Evans spent months in the archives, searching for the evidence and analysing it. The result is a remarkable essay Samuel Griffith and Queensland’s ‘War of Extermination’. I cannot do justice to its development of the evidence, which shows that, far from supporting the excesses of the Native Police and some settlers on the frontiers, Griffith tried to mitigate the violence and prosecute offenders. Evans carefully explains the social and political environment in which Griffith, the politician, was constrained from doing more than he did to limit frontier violence.

If 19th century Queensland politicians were to be indicted for their blame in permitting frontier violence to occur, many would be indicted before Griffith. Evans presents a persuasive case that Griffith would not be indicted, let alone stand as a principal offender. For example, Griffith jointly led with John Douglas a progressive group that was unsuccessful in demanding a Royal Commission into the activities of the Native Police.

“… far from supporting the excesses of the Native Police and some settlers on the frontiers, Griffith tried to mitigate the violence and prosecute offenders. “

Based on their independent research, Professor Mark Finnane and Dr Jonathon Richards published a response to Professor Henry Reynolds’ claims about Griffith in an Australian Historical Studies article, S W Griffith: A Suitable Case for Indictment? They observe that the “list of Griffith’s omissions and commissions cannot leave out repeated statements and actions that expressed his view that violence against Aboriginal British subjects was not acceptable and should be dealt with severely”.

Finnane and Richards describe Griffith “as a figure of his time and empire – a Diceyan figure committed to the rule of law, unshaken in his view of the superiority of British institutions of Law and Governance”. They write that Griffith “warned of the dangers of a caste society (and undemocratic government) arising from the labour competition of unrestricted Chinese or ‘Polynesian’… immigration”. I would add that, like the labour movement and most politicians of his time, Griffith was concerned with exclusion of non-White outsiders, rather than the place and fate of indigenous people.

Recently, Raymond Evans built upon his essay in the first Selden Lecture for 2024: The Rigours of Truth-Telling: Sir Samuel Griffith and Queensland’s Violent Frontier. The event in The Banco Court was co-hosted by the Supreme Court Library Queensland and Griffith University. It is a remarkable lecture about curiosity, historical inquiry, truth-telling and Griffith’s actions and attitudes to the murder of Aboriginal People by Native Police.

Evans explains that Griffith was working within a political and social environment that supported extermination of Aboriginal People who resisted the taking of their country by squatters and other interests. Griffith favoured the abolition of the Native Police because of its excesses, but abolition was politically impossible. Instead, during his relatively brief time as Colonial Secretary, Griffith implemented changes that Evans describes as “unique and piecemeal, though progressive and expanding, policy measures”. In summary, Evans’ research discloses (in his words):

- “A radical attrition of Native Police services;

- Implementation of normalised policing;

- Novel introduction of Aboriginal court testimony;

- An attempted initiative to rein in the frontier ‘black-birding’ of Aboriginal workers;

- Prosecution of white frontier crimes inflicted on First Nation peoples; and

- The burgeoning of missionary enterprise across the North.”

Evans more than responds to claims that Griffith should bear primary responsibility for genocide. He elevates the analysis above selecting politicians for individual blame to a broader ‘systems analysis’ of the political, class and economic interests that drove the violent acquisition of land from Aboriginal People and the relatively few who ultimately benefited from their brutal dispossession.

Often, we are told that we live in a post-truth world. Despite this, many of us in science, the humanities, or the law adhere to the idea that, while the truth may be contested, it exists. It is worth searching for.

In the daily work of courts, judges hear honest individuals’ competing versions of the truth: what was said at a meeting that occurred 5 years ago, or who threw the first punch. Often it is hard to believe that these honest witnesses were in the same place. In some cases, we are aided by contemporaneous documents, independent witnesses, or CCTV images that help us work out what actually happened.

A wise judge wrote in a civil case about the processes of memory being overlaid, often subconsciously, by perceptions or self-interest. McLelland CJ in Equity added, “[a]ll too often what is actually remembered is little more than an impression from which plausible details are then, again often subconsciously, constructed”.[4]

“Griffith was working within a political and social environment that supported extermination of Aboriginal People who resisted the taking of their country by squatters and other interests.“

Despite these challenges in locating the truth, courts try to work out what happened, and to choose between different versions of the truth.

Part of the exercise is assembling the evidence, including contemporaneous documents. Historians do the same. Lawyers spend thousands of hours reviewing emails and other documents. Professional historians spend thousands of hours in the archives.

Next, one draws inferences from the evidence: including reasonable inferences about the intentions and purposes of players. What was someone’s intent or purpose in doing something, or not doing something? Often, these are hard or impossible questions to confidently answer.

Historians, musicians, literary studies scholars, and lawyers also are in the business of interpretation. What is the best interpretation of historical facts, a musical score, a poem, a contract, or a statute. There may be more than one reasonable interpretation. That is why Dr Evans’ work is called A History of Queensland, not The History of Queensland.

In 1975, Raymond Evans co-authored the ground breaking work Race Relations in Colonial Queensland: A History of Exclusion, Exploitation and Extermination. He wrote the part about Indigenous People. Kay Saunders wrote the part about Melanesians and Kathryn Cronin wrote the part about attitudes and responses towards Chinese People in colonial Queensland.

In addition to undertaking important research, Raymond Evans and Kay Saunders had the burden of teaching hundreds of undergraduates each year. I was fortunate to be one of the hundreds of 17-year-olds who they lectured and tutored in 1976. Evans and Saunders brought to lectures and tutorials a depth of knowledge. Their lectures were prepared, organised, and delivered with enthusiasm. Almost 50 years later, their lectures and tutorials remain vivid in my memory and in the memories of my contemporaries.

Research can have an impact. Good teachers do too.

One of my contemporaries in 1976 went on to do race relations courses taught by Evans and Saunders. She wrote to me the other day that their courses “opened my eyes”. Opened my eyes. Those three words capture the essence of a university education, and the work of good academics: past, present and emerging.

Recently, Emeritus Professor Saunders co-presented with Dr Andrew Stumer KC a Selden Society lecture about kidnapping and slavery in Queensland and trials in the Supreme Court arising from two slave ships. Their papers and the video are in the Selden Society Lecture Program.

Raymond Evans continues to research and write. His work, ‘Genocide in Northern Australia 1824-1928’ is part of The Cambridge World History of Genocide, which was published last year. After not seeing him for decades, in 2020, I prevailed upon him to give a short talk about Griffith’s early life. His talk blossomed into an article, Griffith’s Welsh Odyssey, in Griffith Review.

His Selden lecture, titled ‘The Rigours of Truth-Telling’, can be read on-line. A subtitle might be “Raymond Evans’ Griffith Odyssey”. It maps Evans’ challenging and long solo voyage: his odyssey in the historical archives. The talk reports his curiosity, his initial disposition to support Reynolds’ condemnation of Griffith, his search for the evidence, and being prepared to change his mind in the light of the evidence.

“In the daily work of courts, judges hear honest individuals’ competing versions of the truth: what was said at a meeting that occurred 5 years ago, or who threw the first punch. Often it is hard to believe that these honest witnesses were in the same place.”

Evans observes that it is “ironic that the lone public figure who apparently attempted, however inadequately, to challenge the mayhem [of a land-taking venture that was steeped in bloodshed] should now be freighted with the principal blame for it.” He concludes:

“Griffith was neither a monster nor a saint. In determining his specific role, it is probably best not to be too certain in mounting clamorous, angry calls for redress, bearing in mind that truth-telling, where history is concerned, can be multi-layered, elusively structured, endlessly surprising and perhaps at times chimerical.

For, even after the rigorous application of exhaustive research, history remains mercurial and subject to change – within reach without falling into one’s final definitive grasp. The ‘rigours of truth-telling’ warn us never to be too sure of the outcome.”

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith, 1886. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

[1] R B Joyce,‘Sir Samuel Walker Griffith (1845-1920)’(1983) Australian Dictionary of Biography, online at https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/griffith-sir-samuel-walker-445.

[2] Ned Blackhawk et al (eds), The Cambridge World History of Genocide (2023, Cambridge University Press).

[3] Mark Finnane and Jonathon Richards, ‘S W Griffith: A Suitable Case for Indictment?’ (2023) 54(3) Australian Historical Studies 387.

[4] Watson v Foxman (1995) 49 NSWLR 315, 318–9.

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith, 1886. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith, 1886. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.