FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 96: June 2024, Regional Bar

Members of the Queensland Bar are briefed to appear not just in the substantial and well-equipped court complexes of Brisbane and the provincial cities, but also the raft of courthouses in towns throughout Queensland. The latter enjoy the services of a resident Magistrate or are visited on circuit. These courthouses vary in age, size and amenity. Some are colourfully designed or finished, reflecting regional or cultural history. Others have seen better days, with the remaining sitting days perhaps numbered. Whatever the position, such a courthouse is where justice issues are argued by the legal profession and adjudicated by the magistracy (and occasionally higher court judges).

The Editor, Richard Douglas and the Deputy Editor, John Meredith recently had the privilege of meeting with the Chief Magistrate, her Honour Judge Brassington, together with her two Deputy Chief Magistrates. That was undertaken in an endeavour to involve the magistracy more closely in the content of Hearsay. We thank them for their generous response, this item being an example of material assembled by Magistrates in Queensland. Thanks go in particular to their Honours Magistrates Sinclair, Mossop, McLennan and MacKenzie.

The Queensland Bar thanks the magistracy for their sterling service in – with the assistance of the Bar – providing justice services to Queensland in the country courthouses of our vast decentralised state.

Below is a selection of photographs of the 115 courts located outside the South East Queensland coastal strip. In addition, Magistrate Mossop takes us back in time to a trial conducted in the Dalby courthouse in 1967, the case finding its way then to the Court of Criminal Appeal.

Atherton Courthouse

Beaudesert Courthouse

Birdsville Courthouse

Charleville Courthouse

Charters Towers Courthouse

Clermont Courthouse exterior

Clermont Courthouse interior

Coen – Mobile office on the tarmac

Dalby Courthouse

Doomadgee Courthouse and Police Station

Gympie Courthouse

Innisfail Courthouse

Kowanyama Courthouse

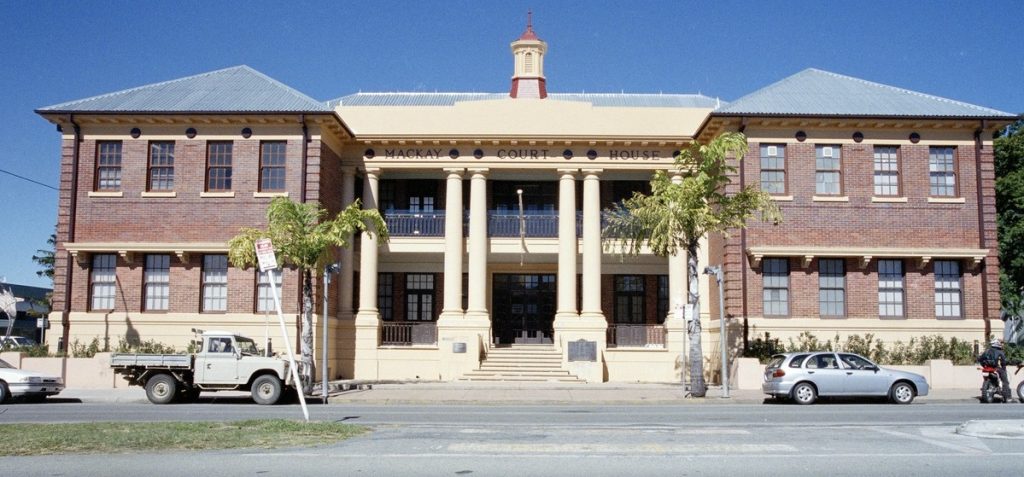

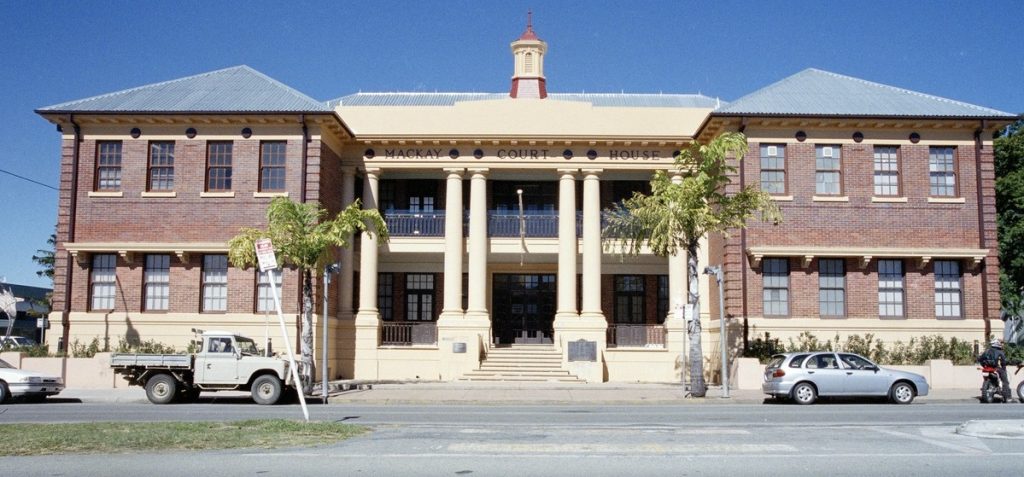

Mackay Courthouse

Mornington Island Courthouse

Murgon Courthouse and Government Offices

Nanango Courthouse

Normanton Courthouse

St George Courthouse

Stanthorpe Courthouse

Thursday Island Courthouse

Warwick Courthouse

Magistrate Tracy Mossop writes:

The year was 1967 and below was one of the cases dealt with in Dalby, as recorded and found in a hand typed court record book. This is a summary of the nine page Court of Appeal decision. An interesting read as to both the criminal law practices at the time and comments on the limited involvement of women in this arena at this time.

The appellant was charged and found guilty of wilful murder at Cloncurry of one D. He appealed on a number of grounds.

“Stripped of verbal trimmings, the short story as it comes from the Appellant is this. On 22 April 1967, the appellant was at Cloncurry where centenary celebrations were being held. During the day, he had about 30 beers of varying sizes. When he drove away from town in the early evening he was fairly sober ‘but he wouldn’t say real sober’. Travelling towards Mount Isa his wife ‘kept going for him’ and when they got some miles out she threatened to open the car door and jump out. The children who were also passengers started to cry, so he pulled the car well off the road and stopped it, and started to get out some gear for the cooking of a meal. As he was doing this his wife said to him something to the effect that she should throw herself under the first car to come along the road. The nature of the country shown in the photographs exhibited is open and undulating. He did not regard this seriously. She walked away and crossed the road. He heard a car coming from Mount Isa and saw its lights, but he was not concerned about it. Nothing he saw of the car or of its speed caused him any concern. He heard a bump, turned and saw a car stopping on the Cloncurry side of where his own car was. He ran across the road and saw his wife lying with one of her legs torn off.”

The evidence after this differed from his police interview and the appeal. He gave evidence of going to his car and getting his rifle, running back to where his wife was, falling over and hearing a shot go off. He did not intend to hurt anyone. But there was evidence of a struggle and the gun going off during a struggle. He also told police he was over near his wife, after he got his rifle and bullets, he ran across the road, remembered he was washing her face, some men came along who then tried to take his wife away so he wrestled with them.

On both accounts the appellant recalls getting the rifle and “detonation”. There was evidence of one shot fired and it hit D in the buttock and came out of his groin. He died some hours later whilst lying moaning about 20 to 25 feet from where the appellant was leaning over his wife and repeating “I’ll shoot the bastard” and similar words. When police arrived, he said to them after a struggle with them and said multiple times “I will kill the bastard” and “what good is she to me with only one leg”.

The primary defence at trial was accident. Defence counsel was a Mr Kneipp. (It has not escaped me that Mr Kniepp is the George Kniepp who went on to be appointed to the judiciary himself). The taking of evidence (including legal argument) went for 2 days. Counsels’ addresses occupied the jury for 3 hours. Summing up lasted more than 3 hours.

As quoted from this case, “But let it be quite clearly understood that jurors, at any rate in Queensland, while they are no doubt endowed with the kind of capacity to which Viscount Birkenhead referred to in The Volute (1922) 1 AC 129…which enables them to deal with questions ‘somewhat broadly and upon common-sense principles’, are not connoisseurs of semantic niceties…It is an everyday experience for the judge presiding at a criminal trial to see how regularly the few whose given occupations indicate the likelihood for even small executive talent are challenged as they come forward. The average Queensland Criminal Court jury consists of entirely men who work for their weekly wage with their hands and who are not accustomed to sit listening closely for hours to evidence, speeches and dissertations upon law. A recent list of what are therein called “criminal jurors” is before me now. It contains over 70 names. The bulk of names are linked with trades, and I would venture to say that even the few whose occupations are given as manager, accountant, engineer, insurance officer, salesman or director are not by those occupations qualified to appreciate legal hair-splitting. … We take men of this kind…to decide…must be unanimous…a consensus of opinion upon important matters, which it would be practically impossible to get from a group of twelve lawyers…They are not trained to select what should be noted down, nor could they take down a useful note of what is given them at conversational speed…The judge of first instance has always to remember that he is addressing, not a panel of skilled and critical lawyers, but men limited to the kind of cross-section of the community I have tried to describe. (I do not at this time mention female jurors who so far in Queensland have been few and far between.)

Hence to say that a summing up is wrong because it does not follow the words of a particular case is unreal. So long as the trial judge has given the lay people whom he is addressing the sense of law in his own language, attuned to his assessment of their understanding, he has done that duty…every judge must be left to sum up a case in his own way so long as he does not misdirect the jury in law or in fact R v Roberts (1942) 1 All ER 187…Legal language may be certain, but it is over the heads of the jury and tends therefore to be very largely ignored…”

“In evidence, his story was that the shot was fired accidentally as he was falling over, and in the record of interview his story was recorded as being that he fired at a chap coming up the road. The defences of accident, insanity and diminished responsibility were fully and properly explained to the jury.” The appeal was ultimately dismissed.

Atherton Courthouse

Atherton Courthouse

Beaudesert Courthouse

Beaudesert Courthouse

Birdsville Courthouse

Birdsville Courthouse

Charleville Courthouse

Charleville Courthouse

Charters Towers Courthouse

Charters Towers Courthouse

Clermont Courthouse exterior

Clermont Courthouse exterior

Clermont Courthouse interior

Clermont Courthouse interior

Coen – Mobile office on the tarmac

Coen – Mobile office on the tarmac

Dalby Courthouse

Dalby Courthouse

Doomadgee Courthouse and Police Station

Doomadgee Courthouse and Police Station

Gympie Courthouse

Gympie Courthouse

Innisfail Courthouse

Innisfail Courthouse

Kowanyama Courthouse

Kowanyama Courthouse

Mackay Courthouse

Mackay Courthouse

Mornington Island Courthouse

Mornington Island Courthouse

Murgon Courthouse and Government Offices

Murgon Courthouse and Government Offices

Nanango Courthouse

Nanango Courthouse

Normanton Courthouse

Normanton Courthouse

St George Courthouse

St George Courthouse

Stanthorpe Courthouse

Stanthorpe Courthouse

Thursday Island Courthouse

Thursday Island Courthouse

Warwick Courthouse

Warwick Courthouse