CIVIL APPEALS

CIVIL APPEALS

Hutchinson & Anor v Equititour Pty Ltd & Ors [2010] QCA 104 Muir JA Chesterman JA Peter Lyons J 7/05/2010

General Civil Appeal from the District Court — Limitation of Actions — Simple Contracts, Quasi-Contracts and Torts — Accrual of Cause of Action and When Time Begins to Run — The appellants entered into a contract dated 18 December 1996 to purchase a unit (Lot 179) from the first respondent (Equititour) in a development then being carried out, and described as the Radisson Palm Meadows Resort and Conference Hotel (the Resort) — The contract settled on about 9 April 1998 — The appellants commenced the present action on 21 July 2006, claiming damages against all defendants for negligence pursuant to s 100 of the Fair Trading Act 1989 (Qld) (FTA) and s 82 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA) — Summary judgment was given for the respondents — In essence, the appellants alleged that representations were made to them prior to entry into the contract about financial returns they would receive if they purchased Lot 179 — Returns were guaranteed for the first five years of the lease to Radisson — The project was not successful, and Radisson elected not to exercise the option to renew the lease — The guaranteed return was paid until about December 2002, but a lesser amount was received for subsequent periods — The appellants alleged that the causes of action on which they sue did not accrue until about December 2002, and their action was commenced within the relevant limitation periods — On Appeal — The onus of pleading and proving the matters which bring s 38 of the Limitation of Actions Act 1974 (Qld) rests on the appellant — No evidence was adduced on behalf of the appellants to demonstrate when they discovered the matters which they allege constitute the fraudulent conduct of Equititour and Radisson — There can be no doubt that the appellants suffered a loss, by reference to the “true value” of Lot 179, (at the latest) when the contract settled — There is evidence that the appellants could not have discovered, either at the date they entered into their contract, or on the date of its settlement, that the “true value” of Lot 179 was less than the purchase price — The price which the appellants paid for Lot 179 was consistent with its market value at that time — The appellants’ causes of action accrued, at the latest, when the contract settled in 1998 — On any view, any capital loss suffered by the appellants occurred before the limitation date — The transaction costs were incurred at about the time the contract was entered into and settled, and the cause of action based on this loss also accrued before the limitation date — HELD: Appeal dismissed with costs.

Neumann Contractors Pty Ltd v Traspunt No 5 Pty Ltd [2010] QCA 119 Holmes JA Muir JA Chesterman JA 21/05/2010

General Civil Appeal from the Supreme Court, Trial Division — General Civil Appeal — Contracts — Building, Engineering and Related Contracts — Remuneration — Statutory Regulation of Entitlement to and Recovery of Progress Payments — The respondent sought summary determination for a debt owing under s 19 of the Building and Construction Industry Payments Act 2004 (Qld) (the Act) — Both parties treated the application as an application for summary judgment under r 292 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld) — On 11 November 2009 the primary judge gave judgment for the respondent against the appellant in the sum of $683,558.15 (including interest) with costs — On Appeal — The respondent entered into a contract with the appellant on about 10 January 2008 under which the respondent agreed to perform for the appellant engineering works for a development being undertaken by the appellant at Caboolture — It was common ground that the contract was a “construction contract” within the meaning of that term in the Act, that the subject work was “construction work” and that the appellant failed to serve a payment schedule on the respondent within the time allowed by s 18 of the Act — A claim by the respondent for the payment of moneys was sent to the appellant’s parent company in May 2009 “the First Claim” — The payment claim the subject of the originating application was submitted to the appellant under cover of letter from the respondent dated 10 June 2009 “the Payment Claim” — The letter enclosing the First Claim was addressed to the appellant’s parent company, but the claim itself correctly identified the respondent as the principal — The fact that the covering letter was addressed to the appellant’s parent company which, on the face of it, shared the same offices as the appellant, does not merit the conclusion that service on the appellant was not effected — Mr Trask, a director of the appellant swore that it was — The respondent argued that the appellant is prevented from taking the point now under consideration by operation of s 19(4) of the Act – A review of authorities provides some support for the primary judge’s approach but its vice is that it fails to consider sufficiently the statutory prescription — It is essential to have regard to the words of s 19(4) in determining whether or not it prevents a defence being raised — Section 19(4)(b)(ii) prohibits the raising of a defence only if it can fairly be described as one which relates to matters arising under the relevant construction contract — The appellant has “a real prospect of successfully defending all or a part of (the respondent’s) claim” [r 292 UCPR] on the grounds that the Payment Claim was a second payment claim served in relation to the same reference date and was thus unable to be relied on by the respondent — The primary judge’s assessment of the nature of the change between the First Claim and the Payment Claim on the one hand and the earlier claims on the other, gave no or insufficient weight to the evidence of Mr Trask that “all prior claims (save for claims 1 to 5) were made under” the Act — The circumstances identified by counsel for the appellant give rise to an arguable case that the conduct of the respondent in changing the basis of its claims without first alerting the appellant to the change was in breach of s 52 — The evidence does not suggest that anything had occurred to put the appellant on notice that the respondent was contemplating changing existing claim procedures and that , in consequence, claims had to be scrutinised with particular care — Whilst the primary judge dealt with the matter carefully and skilfully the range and complexity of the issues before the primary judge and the existence of factual disputes rendered the granting of summary judgment overly bold — HELD: Appeal allowed, judgment and order made on 11 November 2009 be set aside with costs.

Neumann Contractors Pty Ltd v Traspunt No 5 Pty Ltd [2010] QCA 119 Holmes JA Muir JA Chesterman JA 21/05/2010

General Civil Appeal from the Supreme Court, Trial Division — General Civil Appeal — Contracts — Building, Engineering and Related Contracts — Remuneration — Statutory Regulation of Entitlement to and Recovery of Progress Payments — The respondent sought summary determination for a debt owing under s 19 of the Building and Construction Industry Payments Act 2004 (Qld) (the Act) — Both parties treated the application as an application for summary judgment under r 292 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld) — On 11 November 2009 the primary judge gave judgment for the respondent against the appellant in the sum of $683,558.15 (including interest) with costs — On Appeal — The respondent entered into a contract with the appellant on about 10 January 2008 under which the respondent agreed to perform for the appellant engineering works for a development being undertaken by the appellant at Caboolture — It was common ground that the contract was a “construction contract” within the meaning of that term in the Act, that the subject work was “construction work” and that the appellant failed to serve a payment schedule on the respondent within the time allowed by s 18 of the Act — A claim by the respondent for the payment of moneys was sent to the appellant’s parent company in May 2009 “the First Claim” — The payment claim the subject of the originating application was submitted to the appellant under cover of letter from the respondent dated 10 June 2009 “the Payment Claim” — The letter enclosing the First Claim was addressed to the appellant’s parent company, but the claim itself correctly identified the respondent as the principal — The fact that the covering letter was addressed to the appellant’s parent company which, on the face of it, shared the same offices as the appellant, does not merit the conclusion that service on the appellant was not effected — Mr Trask, a director of the appellant swore that it was — The respondent argued that the appellant is prevented from taking the point now under consideration by operation of s 19(4) of the Act – A review of authorities provides some support for the primary judge’s approach but its vice is that it fails to consider sufficiently the statutory prescription — It is essential to have regard to the words of s 19(4) in determining whether or not it prevents a defence being raised — Section 19(4)(b)(ii) prohibits the raising of a defence only if it can fairly be described as one which relates to matters arising under the relevant construction contract — The appellant has “a real prospect of successfully defending all or a part of (the respondent’s) claim” [r 292 UCPR] on the grounds that the Payment Claim was a second payment claim served in relation to the same reference date and was thus unable to be relied on by the respondent — The primary judge’s assessment of the nature of the change between the First Claim and the Payment Claim on the one hand and the earlier claims on the other, gave no or insufficient weight to the evidence of Mr Trask that “all prior claims (save for claims 1 to 5) were made under” the Act — The circumstances identified by counsel for the appellant give rise to an arguable case that the conduct of the respondent in changing the basis of its claims without first alerting the appellant to the change was in breach of s 52 — The evidence does not suggest that anything had occurred to put the appellant on notice that the respondent was contemplating changing existing claim procedures and that , in consequence, claims had to be scrutinised with particular care — Whilst the primary judge dealt with the matter carefully and skilfully the range and complexity of the issues before the primary judge and the existence of factual disputes rendered the granting of summary judgment overly bold — HELD: Appeal allowed, judgment and order made on 11 November 2009 be set aside with costs.

Yara Nipro P/L v Interfert Australia P/L [2010] QCA 128 Muir JA Fraser JA Ann Lyons J 28/05/2010

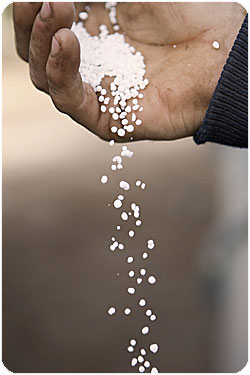

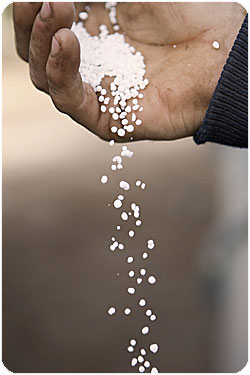

General Civil Appeal from the Supreme Court, Trial Division — Contracts — General Contractual Principles — Construction and Interpretation of Contracts — The respondent manufactures liquid fertilizer, using tonnes of urea from Australian manufacturers and from several importers — In December 2007 the appellant contracted to sell to the respondent 4,000 tonnes of prilled urea originating from Russia or Ukraine — The trial judge held that the appellant was liable for breach of contract and assessed damages at $840,048.69; that amount was set off against the appellant’s admitted counterclaim, resulting in a net judgment in the appellant’s favour of $77,058.65 — A contract for the supply of 2,000 tonnes by the appellant to the respondent was signed on 12 December 2007 — In late December this amount was increased to 4,000 tonnes — During January 2008 it became clear to the appellant that a third party would not supply the prilled urea in time for the appellant to supply it to the respondent by the contract delivery date of 11 February 2008 — Subsequently the respondent made a series of purchases of granulated urea from the appellant at the price of $580 per tonne — The appellant continued to pursue the third party for performance of its contract — The respondent terminated the contract on 30 September 2008 — On Appeal — The appellant accepted that it bore the onus of proving that clause 7 of the contract (the “force majeure” clause) relieved it of liability of its breach of contract — Clause 7 must be construed in the context that the parties did not advert to the question whether or not alternative sources of the specified product were available to the respondent — Neither party adverted to any potential difficulty in the appellant finding an alternative source of supply and the identity of the third party was not disclosed to the respondent before the contract was made — Cross Appeal — The only component of the calculation of damages in issue is the amount to be allowed to Nipro (the cross appellant) as its cost of buying granulated urea in substitution for the prilled urea that Interfert (the cross respondent) had contracted to buy — This case falls squarely within Ogle v Earl Vane (1868) LR 3 QB 272, that is regarded as authority for the proposition that where the time fixed for delivery is postponed at the seller’s request, but the seller fails to deliver the goods at or before the postponed date of delivery the buyer’s damage for non-delivery should be assessed on the basis of the market price at the latter date — The market price for granulated urea having risen, it would be manifestly unjust in these circumstances to limit the assessment of Nipro’s damages by reference to the cost of its purchases at the price prevailing earlier in the year — In the event that Nipro succeeded on its cross appeal, Interfert did not challenge the appropriateness of allowing $3,537,975.20 as Nipro’s cost of buying 4,000 tonnes of granulated urea during October to December 2008 instead of the $2,548,053.60 allowed by the trial judge as the cost of Nipro’s purchases of granulated urea between February and July 2008 — HELD: Appeal dismissed, cross appeal allowed, set aside the orders made by the trial judge and order Interfert to pay Nipro an amount fixed by the Court, either by agreement between the parties, or if no agreement by written submissions, with costs.

Yara Nipro P/L v Interfert Australia P/L [2010] QCA 128 Muir JA Fraser JA Ann Lyons J 28/05/2010

General Civil Appeal from the Supreme Court, Trial Division — Contracts — General Contractual Principles — Construction and Interpretation of Contracts — The respondent manufactures liquid fertilizer, using tonnes of urea from Australian manufacturers and from several importers — In December 2007 the appellant contracted to sell to the respondent 4,000 tonnes of prilled urea originating from Russia or Ukraine — The trial judge held that the appellant was liable for breach of contract and assessed damages at $840,048.69; that amount was set off against the appellant’s admitted counterclaim, resulting in a net judgment in the appellant’s favour of $77,058.65 — A contract for the supply of 2,000 tonnes by the appellant to the respondent was signed on 12 December 2007 — In late December this amount was increased to 4,000 tonnes — During January 2008 it became clear to the appellant that a third party would not supply the prilled urea in time for the appellant to supply it to the respondent by the contract delivery date of 11 February 2008 — Subsequently the respondent made a series of purchases of granulated urea from the appellant at the price of $580 per tonne — The appellant continued to pursue the third party for performance of its contract — The respondent terminated the contract on 30 September 2008 — On Appeal — The appellant accepted that it bore the onus of proving that clause 7 of the contract (the “force majeure” clause) relieved it of liability of its breach of contract — Clause 7 must be construed in the context that the parties did not advert to the question whether or not alternative sources of the specified product were available to the respondent — Neither party adverted to any potential difficulty in the appellant finding an alternative source of supply and the identity of the third party was not disclosed to the respondent before the contract was made — Cross Appeal — The only component of the calculation of damages in issue is the amount to be allowed to Nipro (the cross appellant) as its cost of buying granulated urea in substitution for the prilled urea that Interfert (the cross respondent) had contracted to buy — This case falls squarely within Ogle v Earl Vane (1868) LR 3 QB 272, that is regarded as authority for the proposition that where the time fixed for delivery is postponed at the seller’s request, but the seller fails to deliver the goods at or before the postponed date of delivery the buyer’s damage for non-delivery should be assessed on the basis of the market price at the latter date — The market price for granulated urea having risen, it would be manifestly unjust in these circumstances to limit the assessment of Nipro’s damages by reference to the cost of its purchases at the price prevailing earlier in the year — In the event that Nipro succeeded on its cross appeal, Interfert did not challenge the appropriateness of allowing $3,537,975.20 as Nipro’s cost of buying 4,000 tonnes of granulated urea during October to December 2008 instead of the $2,548,053.60 allowed by the trial judge as the cost of Nipro’s purchases of granulated urea between February and July 2008 — HELD: Appeal dismissed, cross appeal allowed, set aside the orders made by the trial judge and order Interfert to pay Nipro an amount fixed by the Court, either by agreement between the parties, or if no agreement by written submissions, with costs.

CRIMINAL APPEALS

Smith v Ash [2010] QCA 112 McMurdo P Fraser JA Chesterman JA 18/05/2010

Application for Leave s 118 DCA (Criminal) from the District Court — Procedure — Costs — Appeals as to Costs — Jurisdiction to Entertain — On 19 June 2008 the respondent, an officer of the Townsville City Council, swore a Complaint and Summons in the Magistrate Court district of Townsville alleging that Smith, the applicant, had parked her sedan in Flinders Street, Townsville on 25 March 2008 “without having paid the prescribed charge” — The next day Smith indicated in writing, signed by her, that she pleaded guilty to the charge and requested the proceeding be dealt with in her absence — The complaint was dealt with in the Magistrates Court pursuant to s 19 of the Justices Act 1886 (Qld) — The respondent was represented on each complaint by a solicitor, Ms Stockall, employed by the Council — Ms Stockall intimated that “in all of these matters” the respondent was asking for orders for costs in addition to a fine: $81.10 for costs of court and $75 professional fees — The fine was imposed and an order made that Smith pay $81.10 costs of court and the sums be referred to SPER for collection with no order made for professional costs — The respondent appealed to the District Court pursuant to s 222 of the Justices Act against the Magistrate’s refusal to order Smith to pay $75 in professional costs — On Appeal — Read literally s 222(2)(c) prohibits any appeal in cases where, as here, a defendant pleads guilty except an appeal concerned with the adequacy of penalty — There is no discernable reason why a plea of guilty should deprive both defendant and complainant of the right to question an order for costs — The prohibition is incongruous and would distort the uniformity of rights to appeal costs orders — The respondent had a right of appeal from the magistrate’s decision to a District Court judge under s 222 Justices Act and that such an appeal was not prohibited by s 222(2)(c) of the Act — It is clear from the transcript of proceedings that the magistrate determined not to award the respondent her professional costs in an attempt to persuade the respondent’s employer, the Council, to adopt alternative and less costly methods of collecting fines for infringement notices from offenders like the applicant — A local government authority like the Council should conduct itself as a model litigant and ordinarily prosecute such matters in a way which, within reason, minimises its costs and the cost to the State — Under s 157 of the Justices Act the magistrate had an unfettered discretion to award costs — The magistrate was entitled to refuse costs for two reasons — Firstly, the magistrate was entitled to conclude that the costs incurred were not reasonably incurred in the circumstances and secondly the magistrate was entitled to exercise her discretion in this way to encourage the Council to minimise, within reason, the expenditure of public monies in the method of collecting such fines in the future — HELD: Application for leave granted, appeal allowed with costs, orders of the District Court set aside with costs.

Smith v Ash [2010] QCA 112 McMurdo P Fraser JA Chesterman JA 18/05/2010

Application for Leave s 118 DCA (Criminal) from the District Court — Procedure — Costs — Appeals as to Costs — Jurisdiction to Entertain — On 19 June 2008 the respondent, an officer of the Townsville City Council, swore a Complaint and Summons in the Magistrate Court district of Townsville alleging that Smith, the applicant, had parked her sedan in Flinders Street, Townsville on 25 March 2008 “without having paid the prescribed charge” — The next day Smith indicated in writing, signed by her, that she pleaded guilty to the charge and requested the proceeding be dealt with in her absence — The complaint was dealt with in the Magistrates Court pursuant to s 19 of the Justices Act 1886 (Qld) — The respondent was represented on each complaint by a solicitor, Ms Stockall, employed by the Council — Ms Stockall intimated that “in all of these matters” the respondent was asking for orders for costs in addition to a fine: $81.10 for costs of court and $75 professional fees — The fine was imposed and an order made that Smith pay $81.10 costs of court and the sums be referred to SPER for collection with no order made for professional costs — The respondent appealed to the District Court pursuant to s 222 of the Justices Act against the Magistrate’s refusal to order Smith to pay $75 in professional costs — On Appeal — Read literally s 222(2)(c) prohibits any appeal in cases where, as here, a defendant pleads guilty except an appeal concerned with the adequacy of penalty — There is no discernable reason why a plea of guilty should deprive both defendant and complainant of the right to question an order for costs — The prohibition is incongruous and would distort the uniformity of rights to appeal costs orders — The respondent had a right of appeal from the magistrate’s decision to a District Court judge under s 222 Justices Act and that such an appeal was not prohibited by s 222(2)(c) of the Act — It is clear from the transcript of proceedings that the magistrate determined not to award the respondent her professional costs in an attempt to persuade the respondent’s employer, the Council, to adopt alternative and less costly methods of collecting fines for infringement notices from offenders like the applicant — A local government authority like the Council should conduct itself as a model litigant and ordinarily prosecute such matters in a way which, within reason, minimises its costs and the cost to the State — Under s 157 of the Justices Act the magistrate had an unfettered discretion to award costs — The magistrate was entitled to refuse costs for two reasons — Firstly, the magistrate was entitled to conclude that the costs incurred were not reasonably incurred in the circumstances and secondly the magistrate was entitled to exercise her discretion in this way to encourage the Council to minimise, within reason, the expenditure of public monies in the method of collecting such fines in the future — HELD: Application for leave granted, appeal allowed with costs, orders of the District Court set aside with costs.

R v Moore [2010] QCA 116 Holmes JA Muir JA Fraser JA 21/05/2010

Appeal against Conviction from the District Court — Particular Grounds of Appeal — Inconsistent Verdicts — Misdirection and Non-Direction — Presentation of Crown Case — The appellant went to trial on two charges of rape — He was convicted on the first, which was particularised as fellatio, and acquitted on the second, which alleged digital vaginal penetration — The appellant was the assistant pastor of a church, and the complainant, M, a was a member of the church community — In September 2006, they became boyfriend and girlfriend — One evening they discussed what she described as her “boundaries”: those aspects of sexual activity which she was unwilling to engage — The appellant made threats about what he would do to her previous boyfriend and his family — M told the appellant to leave — There was a tussle in which he tried to make her masturbate him and she pulled her hand away — M’s account of what followed formed the basis of the two rape counts — The appellant physically pushed her into position and told her she would be sorry if she did not comply — She opened her mouth and he made her perform fellatio, eventually ejaculating into her mouth — He put what felt to her like two fingers, but could have been one, into her vagina — After those events, the appellant remained for the night in M’s bedroom — When M’s sister arrived home, she went into the room to see her sister looking stressed and tired, with her eyes red as if she had been weeping — At some stage later, M told her that the appellant had “crossed her boundaries” — In September 2007, M reported the sexual assaults to a married couple who were also members of the church to which she and the appellant belonged — In February 2008, M made a complaint to the police — On Appeal — There was a rational basis for the different verdicts in this case — The appellant’s handling of M’s vaginal area was plainly a less significant component of the physical encounter — M did not, it appears, give any account of that event until almost a year later — Given the closeness of their accounts, the brevity of whatever had occurred and the relative insignificance of it in the larger context, the jury might well have thought that M’s account of actual penetration was unreliable, though honest; or at least chosen to give the appellant the benefit of the doubt on that basis — The Crown prosecutor drew the jury’s attention to the police interview with the appellant — There were five matters in respect of which, by implication or directly, the jury was invited to regard the appellant as being deliberately untruthful, because of a consciousness of guilt, when he said he could not remember details — They were: whether he had touched M “inappropriately in her privates”; whether M had ever told him that there were places she would not wish him to touch; whether he was aroused during the events in question; whether M had touched his penis of her own accord; and whether oral sex had occurred — His Honour did not give any direction of the kind discussed in Edwards v The Queen (1993) 178 CLR 193 where the majority emphasised the need for any lies relied on to be precisely identified — Here there was no separate articulation by the prosecutor of the alleged lies — The Crown prosecutor clearly put to the jury that the appellant’s stated inability to recall details of what had happened in the encounter amounted to lies designed to conceal his knowledge that M was not consenting — The jury should have been directed that it could not reason in that way unless it was satisfied that the appellant’s apparent equivocations did indeed constitute deliberate lies, told out of a consciousness of guilt rather than for some other extraneous reason — This was a credit case — Without the advantage of seeing M give her evidence this court could not properly reach a conclusion that the appellant was guilty beyond reasonable doubt — HELD: Appeal allowed, conviction is set aside with a re-trial on count one of the indictment ordered.

R v Moore [2010] QCA 116 Holmes JA Muir JA Fraser JA 21/05/2010

Appeal against Conviction from the District Court — Particular Grounds of Appeal — Inconsistent Verdicts — Misdirection and Non-Direction — Presentation of Crown Case — The appellant went to trial on two charges of rape — He was convicted on the first, which was particularised as fellatio, and acquitted on the second, which alleged digital vaginal penetration — The appellant was the assistant pastor of a church, and the complainant, M, a was a member of the church community — In September 2006, they became boyfriend and girlfriend — One evening they discussed what she described as her “boundaries”: those aspects of sexual activity which she was unwilling to engage — The appellant made threats about what he would do to her previous boyfriend and his family — M told the appellant to leave — There was a tussle in which he tried to make her masturbate him and she pulled her hand away — M’s account of what followed formed the basis of the two rape counts — The appellant physically pushed her into position and told her she would be sorry if she did not comply — She opened her mouth and he made her perform fellatio, eventually ejaculating into her mouth — He put what felt to her like two fingers, but could have been one, into her vagina — After those events, the appellant remained for the night in M’s bedroom — When M’s sister arrived home, she went into the room to see her sister looking stressed and tired, with her eyes red as if she had been weeping — At some stage later, M told her that the appellant had “crossed her boundaries” — In September 2007, M reported the sexual assaults to a married couple who were also members of the church to which she and the appellant belonged — In February 2008, M made a complaint to the police — On Appeal — There was a rational basis for the different verdicts in this case — The appellant’s handling of M’s vaginal area was plainly a less significant component of the physical encounter — M did not, it appears, give any account of that event until almost a year later — Given the closeness of their accounts, the brevity of whatever had occurred and the relative insignificance of it in the larger context, the jury might well have thought that M’s account of actual penetration was unreliable, though honest; or at least chosen to give the appellant the benefit of the doubt on that basis — The Crown prosecutor drew the jury’s attention to the police interview with the appellant — There were five matters in respect of which, by implication or directly, the jury was invited to regard the appellant as being deliberately untruthful, because of a consciousness of guilt, when he said he could not remember details — They were: whether he had touched M “inappropriately in her privates”; whether M had ever told him that there were places she would not wish him to touch; whether he was aroused during the events in question; whether M had touched his penis of her own accord; and whether oral sex had occurred — His Honour did not give any direction of the kind discussed in Edwards v The Queen (1993) 178 CLR 193 where the majority emphasised the need for any lies relied on to be precisely identified — Here there was no separate articulation by the prosecutor of the alleged lies — The Crown prosecutor clearly put to the jury that the appellant’s stated inability to recall details of what had happened in the encounter amounted to lies designed to conceal his knowledge that M was not consenting — The jury should have been directed that it could not reason in that way unless it was satisfied that the appellant’s apparent equivocations did indeed constitute deliberate lies, told out of a consciousness of guilt rather than for some other extraneous reason — This was a credit case — Without the advantage of seeing M give her evidence this court could not properly reach a conclusion that the appellant was guilty beyond reasonable doubt — HELD: Appeal allowed, conviction is set aside with a re-trial on count one of the indictment ordered.

R v Clough [2010] QCA 120 Muir JA Fraser JA Applegarth J 25/05/2010

Appeal against Conviction from the Supreme Court, Trial Division — Interference with Discretion or Finding of Judge — General Principles — Statutes — Acts of Parliament — Interpretation — Particular Words or Phrases — The appellant after a trial before a judge sitting without a jury, was found guilty of murdering his wife — The appellant was 38 years of age at the time of the trial, and had a long history of drug abuse — He had been using cannabis since he was 15 and methylamphetamine since he was 32 — He had a psychotic disorder for which he was being treated — On Appeal — The primary judge found, unexceptionally, that the meaning of the word “intoxication” in the Code was a question of law — The ordinary meaning of “intoxication” is wide enough to encompass more than comparatively short-term elation or stimulation and that “intoxication” in s 28(2) of the Code includes the secondary effect of amphetamine consumption from which the appellant was suffering at relevant times — There is no reason to suppose that in excluding intentional intoxication or stupefaction from criminal responsibility afforded by s 27, the legislature had in mind the exclusion only of an intentional intoxication which had a fleeting effect — The purpose of the exclusion in s 28(2) is to deprive a person who has intentionally used a substance to become intoxicated or stupefied of the ability to deny criminal responsibility for his or her acts or omissions on the grounds of lack of mental capacity — There can be no sensible reason for not applying s 28(2) merely because the state of intoxication or stupefaction intentionally caused by the substance used by that person lasts for days rather than hours — The words of s 28(2) contain no express temporal limitation and none is implicit — In order for s 27(1) to apply, there also needed to be a relevant lack of capacity — Where a person is deprived of a relevant capacity by the effects of intoxication on a pre-existing condition, the pre-requisites for release from criminal responsibility are not engaged — The finding that the appellant’s intoxication (if it existed contrary to the appellant’s argument) was intentional was not challenged — Consequently, s 28(2) would clearly operate to prevent the appellant obtaining the benefit of s 28(1) unless the words “some other agent” in s 28(2) were incapable of including an underlying mental disorder such as the condition from which the appellant suffered — It is already plain from s 28(1) that the intoxication to which s 28(2) refers may be caused by a combination of drugs, intoxicating liquor or other substances — HELD: Appeal dismissed.

R v Clough [2010] QCA 120 Muir JA Fraser JA Applegarth J 25/05/2010

Appeal against Conviction from the Supreme Court, Trial Division — Interference with Discretion or Finding of Judge — General Principles — Statutes — Acts of Parliament — Interpretation — Particular Words or Phrases — The appellant after a trial before a judge sitting without a jury, was found guilty of murdering his wife — The appellant was 38 years of age at the time of the trial, and had a long history of drug abuse — He had been using cannabis since he was 15 and methylamphetamine since he was 32 — He had a psychotic disorder for which he was being treated — On Appeal — The primary judge found, unexceptionally, that the meaning of the word “intoxication” in the Code was a question of law — The ordinary meaning of “intoxication” is wide enough to encompass more than comparatively short-term elation or stimulation and that “intoxication” in s 28(2) of the Code includes the secondary effect of amphetamine consumption from which the appellant was suffering at relevant times — There is no reason to suppose that in excluding intentional intoxication or stupefaction from criminal responsibility afforded by s 27, the legislature had in mind the exclusion only of an intentional intoxication which had a fleeting effect — The purpose of the exclusion in s 28(2) is to deprive a person who has intentionally used a substance to become intoxicated or stupefied of the ability to deny criminal responsibility for his or her acts or omissions on the grounds of lack of mental capacity — There can be no sensible reason for not applying s 28(2) merely because the state of intoxication or stupefaction intentionally caused by the substance used by that person lasts for days rather than hours — The words of s 28(2) contain no express temporal limitation and none is implicit — In order for s 27(1) to apply, there also needed to be a relevant lack of capacity — Where a person is deprived of a relevant capacity by the effects of intoxication on a pre-existing condition, the pre-requisites for release from criminal responsibility are not engaged — The finding that the appellant’s intoxication (if it existed contrary to the appellant’s argument) was intentional was not challenged — Consequently, s 28(2) would clearly operate to prevent the appellant obtaining the benefit of s 28(1) unless the words “some other agent” in s 28(2) were incapable of including an underlying mental disorder such as the condition from which the appellant suffered — It is already plain from s 28(1) that the intoxication to which s 28(2) refers may be caused by a combination of drugs, intoxicating liquor or other substances — HELD: Appeal dismissed.

CIVIL APPEALS

CIVIL APPEALS  Neumann Contractors Pty Ltd v Traspunt No 5 Pty Ltd [2010] QCA 119 Holmes JA Muir JA Chesterman JA 21/05/2010

Neumann Contractors Pty Ltd v Traspunt No 5 Pty Ltd [2010] QCA 119 Holmes JA Muir JA Chesterman JA 21/05/2010  Yara Nipro P/L v Interfert Australia P/L [2010] QCA 128 Muir JA Fraser JA Ann Lyons J 28/05/2010

Yara Nipro P/L v Interfert Australia P/L [2010] QCA 128 Muir JA Fraser JA Ann Lyons J 28/05/2010  Smith v Ash [2010] QCA 112 McMurdo P Fraser JA Chesterman JA 18/05/2010

Smith v Ash [2010] QCA 112 McMurdo P Fraser JA Chesterman JA 18/05/2010  R v Moore [2010] QCA 116 Holmes JA Muir JA Fraser JA 21/05/2010

R v Moore [2010] QCA 116 Holmes JA Muir JA Fraser JA 21/05/2010  R v Clough [2010] QCA 120 Muir JA Fraser JA Applegarth J 25/05/2010

R v Clough [2010] QCA 120 Muir JA Fraser JA Applegarth J 25/05/2010