FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 90: Dec 2022, Reviews

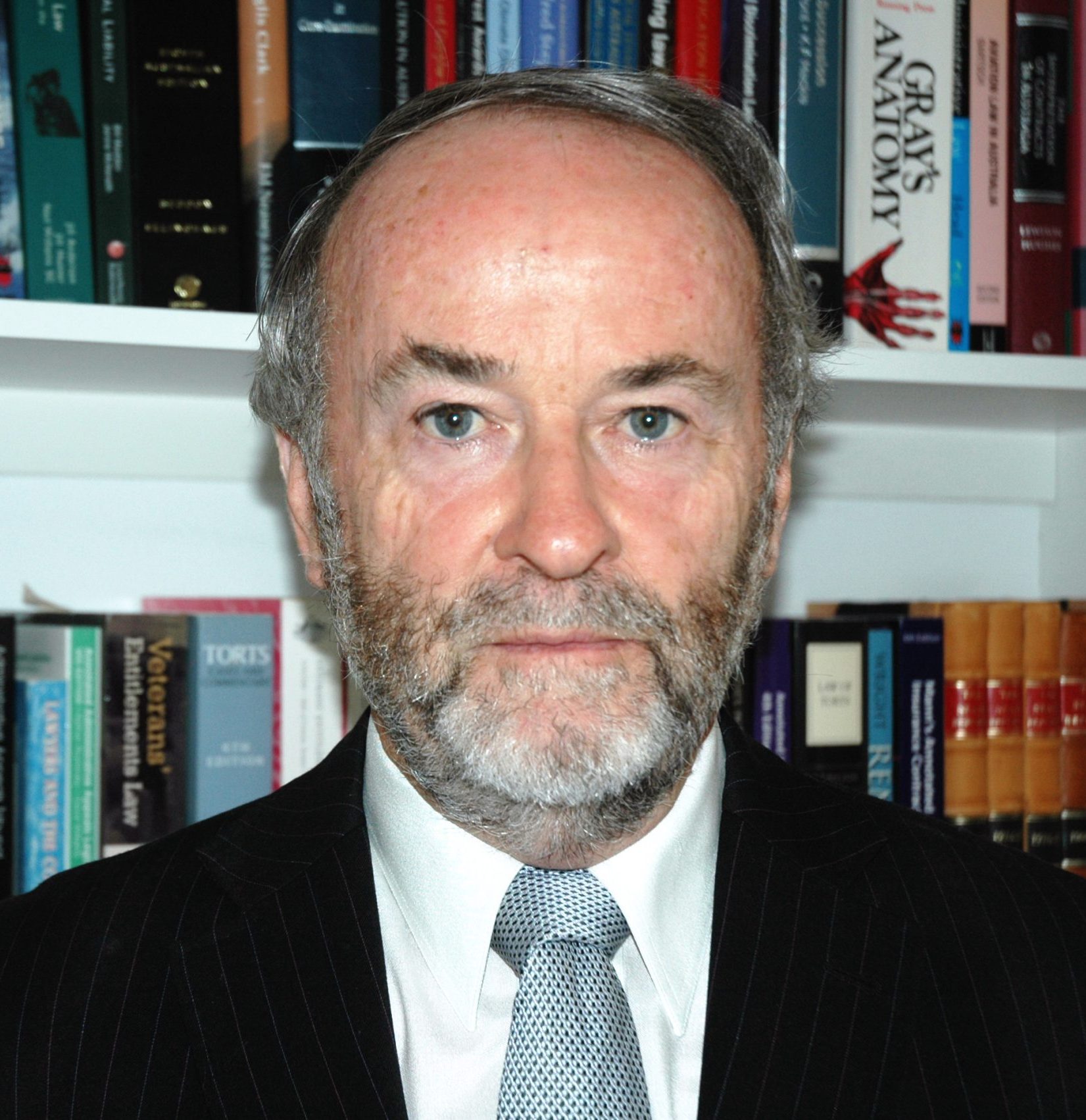

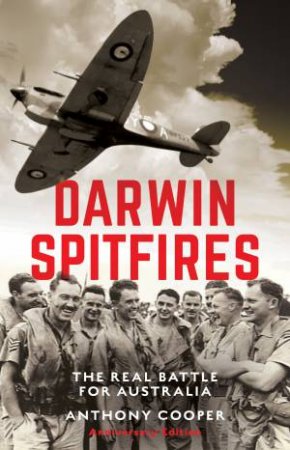

Author: Anthony CooperPublisher: NewSouth Publishing (UNSW)Reviewer: Brian Morgan

If you have been to Darwin recently, I hope you managed to visit the Royal Flying Doctor Tourist Facility at Stokes Hill Darwin. This provides an interactive video and audio display of the first Japanese bombing raid on Darwin in February 1942.

I knew, before reading this book, that there had been later “visits” by Japanese fighters and bombers but I knew few of the details. In fact, I knew a number of the pilots who defended Darwin but, as most such people tend to do, these brave people dismissed their participation as being little more than “showing the flag”.

This book demonstrates that they did far more than that!

I don’t know and can’t comprehend how such detail has been captured, by the author, of the pilots’ sorties against Japanese Zeros and bombers during over 70 raids on the Darwin area during 1942-3.

There are a number of ways that one can interpret this book. One could focus on the suitability of the Spitfires for combat in such a tropical locality. Or, one could concentrate on the tactics used by the Australian aircrews, including their continued trust in the Battle of Britain “Big Wing” where fighters massed in a large assembly prior to seeking to engage an approaching enemy.

Or one could question why the Australians continued to employ certain air tactics when they had been shown, time and time again, to be of little use.

We could wonder at how inaccurate the pilots were when shooting their cannon guns or their .303 machine guns.

Or one could query the apparent lack of fighter combat training given, not only to the RAAF pilots but, also, to many of those from the RAF who were sent to assist in the defence of the Northern Territory of Australia.

Or, you, perhaps like me, feel that this book forces us to think about all of these questions.

I won’t spoil your enjoyment by discussing most of these points in this Review.

There is one comment that one of the pilots made to me in the 1970s which I think is self-evident from the book but which, I think, is worth explaining.

Imagine two aircraft approaching each other at a closing speed of 400-500 knots (about 200 metres per second). In order to hit an approaching aircraft an attacker would need to calculate where it would be when the projectiles reach it, as distinct from where it is at the instant that one fires. For, if you simply aim where the other aircraft is, by the time the ammunition reaches that spot, the aircraft is several hundred metres further on.

Furthermore, in such combat, two aircraft will rarely be heading directly for each other. Neither will they both be maintaining the same altitude so the attacker must also take these variables into account.

Anyone who has shot wild animals at a distance will have suffered the embarrassment of missing, due to not laying off to compensate for the wind strength and direction or the movement of the animal in the several seconds it takes for the projectile to reach its intended destination.

But the Spitfires were travelling a lot faster than a wild animal. The consequence of firing their weapons could cause the direction of the attacking aircraft to yaw to one side, particularly, if one or more of the weapons jammed and didn’t fire. One may observe that “dog fighting” is a skill which requires training and practice.

The Australian pilots did improve their gunnery and their tactics with practice and experience as demonstrated by the statistics gathered by the author. Perceived inaccuracy by the defenders of Darwin needs to be recognised in this context.

The author suggests that a comparison with the results from the Battle of Britain shows that the results achieved over Darwin were in the same league.

You don’t need to be a pilot to be fully engaged by this book. There are human interest aspects of it. One can almost feel the uncomfortable conditions that the pilots had to endure both on the ground and, often, a few minutes later, when flying at 30,000 feet where the temperature has dropped from, say, mid 30°C to below 0°C. One can empathise with their experiences, when not flying, of having to exchange their accommodation for safety trenches dug in the ground to avoid the bombs dropping from above. One can particularly feel for the experiences of the pilots from the UK in coping with such a radically different climate to that with which they were familiar, at home.

This book has somehow, as I mentioned earlier, managed to put together an enormous amount of detailed information concerning the tactics used by many of the pilots in the air. I do not doubt the accuracy of these descriptions but I shake my head at the amount of detail the author has been able to obtain. Darwin Spitfires gains much of its impact from its ability to present such detail.

Finally, this is an updated and improved version of an edition that was published about a decade ago.

The book has been described by retired Air Vice Marshall Weston as, “detailed, forensic and expert”. I, wholeheartedly, agree. I would add that it is a book which also enlightens us as to the actions of the RAAF in defending Darwin after that infamous Japanese raid in February 1942.