MANAGERIAL JUSTICE AND EXPERT EVIDENCE

Case management of civil litigation is now entrenched practice in Australian courts. The rationale underlying case management is that the community has a vital interest in ensuring that litigation is conducted as expeditiously and economically as is consistent with reasonable procedural fairness. A corollary is that if the conduct of litigation is left entirely or largely in the hands of the parties, the consequences will include extensive delays, undue expense and the waste of public and private resources. Accordingly, case management principles entrust primary responsibility to the courts, as distinct from the parties, for minimising delays in finalising litigation, encouraging the parties to explore negotiated or mediated settlement of disputes and ensuring that the costs incurred by the parties are proportionate to the issues at stake. It is no accident that the concept of “managerial justice”1 has now secured not only judicial but legislative endorsement.2

Case management of civil litigation is now entrenched practice in Australian courts. The rationale underlying case management is that the community has a vital interest in ensuring that litigation is conducted as expeditiously and economically as is consistent with reasonable procedural fairness. A corollary is that if the conduct of litigation is left entirely or largely in the hands of the parties, the consequences will include extensive delays, undue expense and the waste of public and private resources. Accordingly, case management principles entrust primary responsibility to the courts, as distinct from the parties, for minimising delays in finalising litigation, encouraging the parties to explore negotiated or mediated settlement of disputes and ensuring that the costs incurred by the parties are proportionate to the issues at stake. It is no accident that the concept of “managerial justice”1 has now secured not only judicial but legislative endorsement.2

In modern times, the excesses of an unrestrained adversary system have been most clearly illustrated by the astonishing costs generated by the discovery process in large-scale civil litigation. The misuse of expert evidence runs a close second. The latter phenomenon has been seen, correctly, to be a direct consequence of the failure of the adversary system, until recently, to incorporate a principle of proportionality in litigation.3 The corrective provided by managerial justice has brought about far reaching changes — perhaps even a revolution — in the way litigation is conducted in Australia. The constraints now imposed on experts and on expert evidence in civil proceedings must be understood in this broader context.

IT WAS NOT ALWAYS THUS

Lawyers have a tendency to think that the practices and procedures inherited from recent generations invariably have ancient origins. While the use of expert evidence by courts can be traced to the fourteenth century, it was not until the eighteenth century that this form of evidence became the preferred means for courts to receive specialised information or opinions. Until then the courts relied heavily on other mechanisms.

The point is illustrated by Buller v Crips,4 a case decided by the Court of King’s Bench in 1703. The Court, presided over by Chief Justice Holt, was confronted with a nice question concerning the status of a promissory note. A purchaser of wine promised to pay the vendor:

The point is illustrated by Buller v Crips,4 a case decided by the Court of King’s Bench in 1703. The Court, presided over by Chief Justice Holt, was confronted with a nice question concerning the status of a promissory note. A purchaser of wine promised to pay the vendor:

“or order, the sum of one hundred pounds, on account of wine had from him”.

The promisee, John Smith, endorsed the note to a third person. That person sued the drawer of the note (not John Smith, the promisee) on the basis that, according to the custom of merchants, the note could be treated as a bill of exchange.

The Court was sceptical about the plaintiff’s argument and doubtful about his assertion that the rejection of his claim would cause commercial inconvenience. To clarify the position, Holt CJ did something very sensible:5

“he had desired to speak with two of the most famous merchants in London, to be informed of the mighty ill consequences that it was pretended would ensue by obstructing this course [advanced by the plaintiff]; and that they had told him, it was very frequent with them to make such notes, and that they looked upon them as bills of exchange, and that they had been used for a matter of thirty years, and that not only notes, but bonds for money, were transferred frequently, and indorsed as bills of exchange.” (Emphasis in original.)

The information provided by the two famous merchants apparently was not cogent enough to persuade the Court that the note should be treated at law as a negotiable bill of exchange.6 Nonetheless, the Chief Justice evidently thought that there was nothing amiss in obtaining the required information simply by asking people with the necessary expertise to provide it to him. This form of inquiry may be difficult to reconcile with modern notions of procedural fairness, but it was certainly expeditious and cheap and perhaps even reliable.

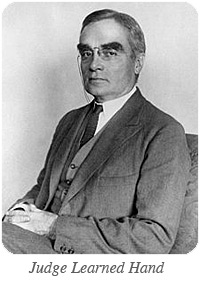

Two centuries later, one of the great American jurists, Judge Learned Hand, wrote a seminal article pointing out that, before the modern trial by jury emerged, courts or other decision-makers obtained the benefit of expert knowledge primarily in two ways.7 The first was to empanel a special jury of persons especially fitted to judge the facts. This procedure grew out of the medieval community-based jury, whose members were chosen because of their knowledge of the facts of the case and was well established by the fourteenth century, particularly in trade disputes.8 Lord Mansfield, a proponent of merchant juries in commercial cases, justified the procedure in a case decided in 1761:9

Two centuries later, one of the great American jurists, Judge Learned Hand, wrote a seminal article pointing out that, before the modern trial by jury emerged, courts or other decision-makers obtained the benefit of expert knowledge primarily in two ways.7 The first was to empanel a special jury of persons especially fitted to judge the facts. This procedure grew out of the medieval community-based jury, whose members were chosen because of their knowledge of the facts of the case and was well established by the fourteenth century, particularly in trade disputes.8 Lord Mansfield, a proponent of merchant juries in commercial cases, justified the procedure in a case decided in 1761:9

“The special jury (amongst whom there were many knowing and considerable merchants) … understood the questions very well, and knew more of the subject than any body else present”.

The second procedure was to seek the advice of skilled persons who could advise the court on matters within their field of expertise. In Buller v Crips, advice was sought and provided informally, outside the courtroom. In even earlier times, courts of admiralty used assessors to sit with the court and provide answers, in private, on technical questions. Indeed, the admiralty courts developed a rule that expert evidence could not be tendered on matters within the expertise of the assessors.10

The modern lawyer is much more familiar with the practice of adducing evidence from experts who are permitted to express opinions on matters within their field of expertise. The origins of the practice apparently lie in a procedure whereby surgeons were summoned to give their opinion on such questions as whether wounds sustained by a victim of crime were fresh.11 As jurors ceased to be locals with personal knowledge of the facts, it became inevitable that witnesses would have to give evidence before the jury on matters within their expertise.12 However, it was not until the eighteenth century, when the rules of evidence became more formalised, that expert evidence was finally held to constitute an exception to the general principle that witnesses could not give opinion evidence.13 The exception is now embodied in legislation that is to be found in virtually all common law jurisdictions that have codified the law of evidence.14

That exception to the exclusionary rule constitutes the foundation stone for the reception of expert evidence in trials. While there are exceptional cases in which the court appoints its own expert or is assisted by an expert assessor, the adversary system has given the parties responsibility for adducing and presenting expert opinion evidence in support of their respective cases. The traditional role of the court has been to evaluate that evidence and, if necessary, to choose between conflicting opinions of the experts. In the age of managerial judging, it is this allocation of forensic responsibilities that is under siege.

EXPERT EVIDENCE: “FERTILE OF INCONVENIENCE”

Learned Hand, while acknowledging the historical reasons for the survival of the expert witness, characterised the practice of receiving expert evidence in court as an “anomaly fertile of much practical inconvenience”.15 He saw it as an anomaly because the expert did not give evidence of facts, but of:

“uniform physical rules, natural laws, or general principles, which the jury must apply to the facts.”’16

The expert, according to Hand, therefore usurps the historical role of the jury (or other fact-finder) to determine the facts.17

At a more practical level, Hand identified serious difficulties with the use of expert witnesses. Given the weakness of human nature, so he argued, it is inevitable that the expert “becomes a hired champion of one side”.18 The jury is confronted with diametrically opposed views on issues beyond its competence to resolve. Hand saw the answer in appointing an expert or experts to advise the jury in discharging its fact-finding function.

In the intervening century or so since his article was published, Learned Hand’s misgivings about the value of expert evidence have been amply borne out. Judges, commentators and professional associations (lawyers and non-lawyers alike), not to mention law reformers, have railed against the evils associated with the use of expert evidence in the adversary system. There is a general, if not universal, recognition that in this respect the court system has clearly failed to achieve its objective of producing just results without a disproportionate expenditure of time and resources.

The problems presented by the use of expert evidence in litigation are well-known and widely documented.19 They include the following :

- too many experts are willing to act as “hired guns” and to give opinions that are the product of partiality, rather than provide an objective and independent assessment of the questions presented;20

- expert evidence is selected by the parties, not necessarily because it is reliable, but because it is thought to advance the interests of one of the litigants;

- the adversarial system of resolving disputes is:

“calculated to bring forward unrepresentative opinions in cases where a range of opinions exist”;

- experts sometimes influence the way in which a case is framed, with the consequential risk that they become the “front line soldier[s]“, propounding the case on behalf of the client, further detracting from their objectivity;2

- the evidence given by experts may be spurious, yet is wrongly assumed by a fact-finder to be authoritative;23

- the preparation of experts’ reports can be extremely expensive and can therefore confer an advantage on well-resourced litigants over their less fortunate opponents;

- over-zealousness or excessive caution in the conduct of litigation frequently lead to wasteful duplication in the preparation and tendering of experts’ reports;

- the testing of expert opinion by cross-examination can be extremely lengthy and thus can contribute not only to disproportionate expense, but to substantial delays in resolving the proceedings;

- reliance on expert evidence has led to the creation of a “large litigation support industry” among various professions, which offends “all principles of proportionality” and creates barriers to access to justice;24 and

- even if experts give their opinions on the basis of an objective analysis of the relevant material, it may be difficult for the court to resolve satisfactorily conflicting opinions on complex technical questions.

THE REFORM MOVEMENT

The arrival of the age of the managerial judge has coincided with reforms designed to eliminate or at least substantially reduce the excesses of the adversary system. In view of the widespread recognition of the unrestrained use of experts in civil proceedings, it is not surprising that the reforms have concentrated on the need to curtail the use of expert evidence.

The Woolf Reforms

A fundamental feature of the Woolf reforms in England and Wales has been the conferral of more extensive powers on courts to control the nature and form of expert evidence that can be given in civil proceedings. Lord Woolf identified the objective of the reforms as being:

“to foster an approach to expert evidence which emphasises the expert’s duty to help the court impartially on matters within his expertise, and encourage a more focused use of expert evidence by a variety of means”.25

To this end, he recommended that the court should have complete control over the use of expert evidence. Indeed, no expert evidence was to be adduced at all at the trial unless it helped the court. Moreover, no more than one expert in any speciality was to give evidence unless “necessary for some real purpose”.

The Woolf reforms have been implemented in England.26 Part 35 of the Civil Procedure Rules (“CPR”) provides that it is the duty of an expert to help the court on matters within his or her expertise and that this duty overrides any instructions from the client.27 No party is permitted to call an expert or put in evidence an expert’s report without the court’s permission.28 Expert evidence must be given in written form only, unless the court directs otherwise.29 An expert may file a written request with the court seeking directions as to the discharge of his or her duty to the court.30 Where two or more parties wish to submit expert evidence on a particular issue, the court may direct that the evidence on that issue be given by one expert only and, if the parties cannot agree, the court may appoint the expert.31 The court, in any event, has power to limit the number of experts giving evidence, either generally or in relation to a particular issue.32 It may also direct the experts at any time to discuss their opinions among themselves, with a view to narrowing the issues in dispute.33 The CPR are supported by a Practice Direction, which fleshes out the general principles. A Code of Guidance on Expert Evidence, among other things, encourages courts to appoint a single joint expert in uncomplicated cases.34

An expanding body of case law provides guidance to the courts as to the manner in which they should exercise their powers in different circumstances.35 The Court of Appeal has expressed the view, for example, that where a report is obtained from a jointly instructed expert, a party dissatisfied with the report ordinarily, at least in substantial claims, should be allowed to obtain a second report.36 However, this is not to be done when the cost of the second opinion is disproportionate to the amount involved. In any event, oral evidence should be taken from experts in personal injury cases only as a last resort.37 The Court of Appeal has also made it clear that it is inappropriate for jointly instructed experts to meet with one party without a representative of the other party being present.38 To do otherwise would be “inconsistent with the whole concept of the single expert” which operates within a framework “designed to ensure an open process”.39

Introducing reforms is one thing; changing forensic practices and the culture of litigation are another. Nonetheless, there is mounting evidence that the Woolf reforms have brought about major changes in the use of expert evidence in England and Wales, particularly in routine cases. Research conducted by the Lord Chancellor’s Department, in the period 2000-2001, for example, suggested that joint experts were used in 45 per cent of trials involving expert evidence and that the percentage was higher in personal injury litigation.40 While some are sceptical as to the success of the new arrangements,41 the trend towards the appointment of joint experts represents, of itself, a significant departure from previously entrenched practice.

Australian Reforms

Reforms to the procedures for taking expert evidence in Australia, although prompted by the same considerations that motivated the Woolf reforms, have taken a somewhat different path. Change has occurred more gradually than in England and no single jurisdiction has adopted the full panoply of Woolf reforms in one fell swoop. Some Australian reforms predated the Woolf proposals and important innovations, such as the practice of experts giving concurrent evidence, were developed by Australian courts or tribunals without prompting by external bodies. Changes have been introduced in four main ways:

- informal practices developed by the courts;

- practice directions issued by courts in an attempt to maximise the utility of expert evidence and to ensure that experts better understand their obligations to the court;

- rules of court, sometimes supported by legislation, which established new procedures and guidelines; and

- judicial decisions refining the principles governing the admissibility of expert evidence, usually by imposing more stringent criteria that must be satisfied.

These are not rigid or mutually exclusive categories. The means by which changes have been introduced vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and over time. Informal innovations are recognised in judicial decisions and rules of court; practice directions become formalised in rules of court; changes introduced by informal means or by practice directions in one jurisdiction may be the subject of rules of court in another. The brief overview which follows illustrates the range of approaches to the control of expert evidence in Australia.42

Informal Innovations

Informal Innovations

Even without practice notes or new rules, courts have introduced new techniques for adducing expert evidence that are designed to elicit information in a less adversarial atmosphere and in a manner that provides greater assistance to the court. The most obvious example is the use of concurrent expert evidence. This technique, first designated as the “hot tub” approach, was developed in the Australian Competition Tribunal and later adopted by the Federal Court, initially for the taking of evidence from economists in competition cases.

Although there is no prescribed procedure for the taking of concurrent evidence, its essential elements were described by the Australian Law Reform Commission:

- “experts submit written statements to the tribunal, which they may freely modify or supplement orally at the hearing, after having heard all of the other evidence

- all of the experts are sworn in at the same time and each in turn provides an oral exposition of their expert opinion on the issues arising from the evidence

- each expert then expresses his or her view about the opinions expressed by the other expert

- counsel cross-examine the experts one after the other and are at liberty to put questions to all or any of the experts in respect of a particular issue. Re-examination is conducted on the same basis.“43

The use of concurrent evidence, where a case justifies more than one expert opinion on a topic, attracted considerable judicial support in a variety of jurisdictions. Justice Peter McClellan, for example, has commented extensively about the successful use of concurrent evidence in the Land and Environment Court and in the Supreme Court of New South Wales.44 His assessment is that a less formal forensic environment enables experts to communicate their opinions more clearly and to respond more effectively to views expressed by the other expert or experts. From the judge’s perspective:

“the opportunity to observe the experts in conversation with each other about the matters, together with the ability to ask and answer each other’s questions, [enhances] the capacity … to decide which expert to accept.”45

As courts have gained more experience with experts giving concurrent evidence, they have formally recognised the practice in rules of court. The Federal Court Rules (“FCR”), for example, now specifically empower the Court to require evidence to be given by experts concurrently.46 So it is that experimental techniques for receiving expert evidence became entrenched in the rules governing the conduct of civil litigation.

Practice Directions

An example of reform through practice notes is provided by the Federal Court’s Practice Direction: Guidelines for Expert Witnesses in Proceedings in the Federal Court. First issued in 1998, the current Practice Direction47 makes it clear that the expert has an overriding duty to assist the Court on matters within his or her field of expertise; that the expert is not an advocate for a party; and that the expert’s duty to the Court overrides that owed to the party using the expert’s services. The Practice Direction specifies in some detail the formal requirements with which the expert’s written report must comply. The requirements include a full and clear statement of all assumptions of fact, reasons for each opinion expressed and a record of the instructions given to the expert and of the documents or other materials the expert has been asked to consider.

Practice notes sometimes specify the procedure to be followed in particular kinds of cases where expert evidence is said to be required. In New South Wales, for example, a Practice Note48 provides that, unless cause is shown, a “single expert direction” will be made in every proceeding in which a claim is made for damages for personal injury or disability. The effect of such a direction, among other things, is that expert evidence is confined to that of a single expert witness in relation to any particular head of damages. Any party may put a maximum of 10 questions to the expert after he or she presents the report but, except with leave, only for the purpose of clarifying matters in the report. A single expert witness may be cross-examined at the trial by any party.

Rules of Court

Almost all Australian jurisdictions now have rules dealing with expert evidence. The Federal Court’s Practice Direction, for example, operates in conjunction with the Federal Court Rules which confer a variety of powers to control the manner in which expert evidence is prepared or adduced. These include, in addition to the power to require evidence to be given concurrently, power to:

- appoint a court expert;49

- order that no more than a specified number of experts be called;50 and

- give directions as to the manner in which expert evidence is to be given, where two or more parties intend to call expert evidence on a similar issue.51

The Federal Court Rules do not, however, prevent parties calling expert evidence without the permission of the Court and make no provision for the appointment of a single expert (except as a court-appointed expert).

The Family Law Rules 2004 (Cth) (“FLR”) go further than those of the Federal Court and follow the English approach of requiring parties who seek to rely on expert evidence to apply to the court for permission to do so.52 The primary objects of the FLR are to restrict expert evidence to what is necessary to resolve significant issues in the case and:

“to ensure that, if practicable and without compromising the interests of justice, expert evidence is given on an issue by a single expert witness.”53

The apparent boldness of the Family Court in requiring permission to adduce expert evidence may well be a product of the specialised nature of its jurisdiction, although family law litigation can vary considerably in complexity and in the monetary value of the issues in dispute.

Queensland introduced comprehensive rules relating to expert evidence in 2004.54 The amendments were intended to declare the duty of the expert witness in relation to the court and the parties; ensure, so far as practicable and without compromising the interests of justice, that evidence is given on an issue by a single expert; and avoid unnecessary costs.55 The overriding duty of the expert is said to be to assist the court.56

The Queensland rules are unusual in that they provide for persons who are in dispute to appoint a joint expert to report on a question before proceedings are instituted.57 If the parties cannot agree, one of the disputants can apply to the court to appoint an expert.58 In either case, unless the court otherwise provides, only that expert can give evidence in proceedings on the relevant question.59 These provisions are intended to provide a mechanism to overcome the difficulty that the appointment of a single expert in the course of litigation often takes place after the parties have already engaged their own experts, and thus already incurred substantial costs.60

The Queensland provisions contemplate that, in general, a single expert will give evidence on a particular issue.61 This is so whether the expert is appointed by the parties or by the court. Thus, although the parties do not require permission of the court to call expert evidence, they are restricted to a single expert unless the court determines that the case justifies an alternative course. Moreover, the court has power, on its own initiative, to appoint an expert to prepare a report on a substantial issue in the proceedings.62

The New South Wales Uniform Civil Procedure Rules are intended “to ensure that the court has control over the giving of expert evidence” and to restrict expert evidence to that which is reasonably required.63 The New South Wales rules do not prohibit a party from calling expert evidence without permission of the court.64 But they require a party intending to adduce expert evidence to seek directions from the court promptly. Expert evidence is not to be adduced until the court has given directions and is to be given only in accordance with those directions.65 The court has broad powers in relation to expert evidence and may direct, among other things, that expert evidence not be adduced on specific issues; that the parties instruct a single expert in relation to a particular issue; that the experts confer prior to giving evidence with a view to preparing a joint report; and that they give evidence concurrently.66

Case law is beginning to emerge in relation to the new regime in New South Wales. In a recent case,67 for example, Brereton J declined to receive a second expert’s report after a jointly appointed engineer had provided a report. His Honour pointed out that the fundamental purpose of appointing a joint expert is to avoid the need for competing reports. While it is no doubt too soon for a definitive assessment of the regime, decisions of this kind suggest that the courts are willing to pay more than lip service to the philosophy underlying the rule changes.

THE IMPACT OF REFORMS

THE IMPACT OF REFORMS

Routine Litigation

It is difficult to measure the impact of court-initiated reforms of the principles and practices relating to expert evidence, at least without elaborate and carefully designed empirical studies. Perhaps not surprisingly, in Australia there appear to have been no detailed empirical research attempting to assess the costs and benefits both to litigants and the court system of the reforms effected variously by practice directions, rules of court and judicial decisions.68 It is not possible, therefore, to be dogmatic about the success of measures designed to curtail, if not eliminate, the generally acknowledged problems with expert evidence such as bias, duplication of reports and testimony, excessive costs, and delays and selectivity in the presentation of expert opinions.

Nonetheless, the reforms provide a framework for curtailing the excesses associated with the use of expert evidence in what might be described (without condescension) as routine or standard cases. In principle, it should be feasible for courts to impose and monitor stringent requirements, such as directing a single expert to report on particular issues or making orders limiting the scope and nature of expert evidence, in particular categories of standard cases. These include personal injury litigation, building and construction disputes, family law proceedings and medical negligence claims. Judges regularly hearing cases of a similar nature should rapidly become sufficiently familiar with recurring issues to utilise their newly acquired powers. Decisions interpreting and applying the new rules, as in the United Kingdom, should encourage judges to exercise their powers with confidence and appropriate vigour. This in turn should have a significant impact on the culture of litigation as practitioners adjust to a new set of forensic imperatives.

These forecasts, however, need to be tested by the regular gathering of empirical evidence as to the effect of procedural reforms. All too often in Australia, evaluation of the success or otherwise of reforms, whether in relation to expert evidence or otherwise, relies almost entirely on anecdotal accounts. Systematic assessment of new forensic practices is uncommon. Regular evaluation of such practices, based on the compilation of reliable statistical data and analyses of the experiences of all participants in the forensic process, is even less common. Research of this kind will be an essential component of the next reform plan.

Large-Scale Litigation

The Challenge

Changing the practices and culture of routine or standard litigation is a formidable enough undertaking. An even more formidable challenge for courts is created by mega-litigation and other large-scale litigation. I have used the term “mega-litigation” to describe:

“civil litigation, usually involving multiple and separately represented parties that consumes many months of court time and generates vast quantities of documentation in paper or electronic form”.69

Mega-litigation is not the only form of large-scale litigation, but it starkly presents the difficulties confronting the courts.

One of the characteristics of mega-litigation is that it almost invariably involves elaborate expert evidence, the reception of which frequently plays a substantial and, indeed, disproportionate part in the proceedings. The evidence may relate to complex technical or scientific issues, for example, in intellectual property cases or product liability claims. Mega-litigation can also give rise to disputed economic issues, such as the definition of markets in competition cases. The relief sought by the plaintiff or applicant, particularly large damages claims, frequently generates detailed and sophisticated (or apparently sophisticated) reports from accountants or financial or industry experts.

Mega-litigation and other forms of large-scale litigation are on the increase.70 There are many reasons for this phenomenon. They include the greater sophistication and complexity of commercial transactions; ever more exquisite technological advances that can be understood only by specialists; the sheer size of multi-national or even local corporations whose disputes involve very high stakes indeed; the uncertainties created by the search for “individualised justice”; and procedural innovations, such as class actions, that are designed to improve access to justice but often generate large-scale litigation.

The challenges facing the courts in managing mega-litigation (or other large-scale litigation) differ from those presented by standard litigation. This is not because the need for judicial supervision of mega-litigation, including the parties’ reliance on expert evidence, is any less than in relation to routine litigation. On the contrary, the evils identified by Learned Hand and later commentators are just as apparent in large-scale litigation, if not more so. The difficulties of managing complex litigation are compounded by several trends that quickly became evident to those embroiled in litigation of that kind.

First, legal practitioners frequently seem to assume that if apparently reputable experts can be found who are prepared to express an opinion that seems to advance the client’s interests, it is imperative to adduce evidence to that effect. Whether the forensic decision is made on the basis of a considered view that the material is probative of the issues in dispute, or simply because of a fear that some litigious stone that may remain unturned, enthusiasm for expert evidence of dubious worth seems to be endemic to modern litigation. On occasions, lawyers may even defer to experts in devising a litigious strategy, not always with a beneficial outcome.71 Nor is it uncommon for a party’s representatives to prepare detailed (and presumably expensive) “expert” reports only to find that tender of the reports is rejected on the ground that the author has not demonstrated that his or her opinions are based on relevant specialised knowledge.72

Secondly, there is a tendency in major litigation for each well-resourced party to support its case by relying on reports from two or more experts covering much the same ground. In multi-party litigation, each party may insist on tendering its own expert report even though they seem to have a substantially common interest in the proceedings, at least on the relevant issues. In the C7 Case, for example, the various parties tendered substantial reports (sometimes more than one) from five experts on market definition issues.73 Despite concerns expressed from the bench as to the apparent duplication involved, parties insisted that they would be prejudiced if they were not permitted to follow their chosen course.

Thirdly, the over-reliance on expert evidence often produces a very large — sometimes staggering — number of individual objections to the admissibility of portions of reports. In the Wongatha native title litigation, for example, 1426 individual objections were made in relation to 30 separate expert reports.74 A judge faced with the need to give rulings on this volume of objections must develop strategies to render the task manageable. Even so, rulings on admissibility may occupy entirely disproportionate court time.

Towards More Stringent Controls

It might be thought that the reforms to which I have referred ensure that courts are well-placed to curb the excesses associated with the over reliance on expert evidence in mega-litigation. The powers conferred on courts to limit expert evidence, for example, would seem to be ample to prevent unnecessary duplication or wasteful expenditure on reports of dubious value. In fact, at least in the very largest cases, it can be surprisingly difficult for the courts to exercise their powers effectively. The parties to mega-litigation are not only extremely well-resourced, but are not necessarily disposed to co-operate with each other or the court to ensure that the expenditure of time, money and effort is proportionate to what is at stake in the proceedings.

The fundamental difficulty facing a court in seeking to exercise stringent control over the use of expert evidence in mega-litigation is what I have described elsewhere as the “information deficit”.75 Even in a system of case management, in which the trial judge manages the litigation from commencement until trial, the most diligent judge cannot know in advance of the hearing anything like as much about a party’s case as that party’s legal representatives. The judge may have serious doubts, for example, about the utility of expert evidence the parties intend to adduce, but a ruling preventing the parties from relying on the evidence they consider important may be thought to imperil a fair trial. Bearing in mind that a trial judge is bound not to compromise his or her independence and impartiality, a considerable degree of caution is usually required before overriding the parties’ own assessment of the evidence needed to support their respective contentions.

If the procedural reforms relating to expert evidence are to have their intended effect in relation to mega-litigation and other large-scale civil proceedings, the judiciary will have to be prepared to adopt even more rigorous and interventionist pre-trial case management strategies. To minimise the likelihood of successful challenges to the exercise of powers by trial judges, judges require explicit statutory authority to curtail and regulate the use of expert evidence in mega-litigation, even over the express opposition of one or more of the parties. The powers should be exercised so as to ensure that the projected costs, not merely in terms of direct expense but in court time and delay in finalising the proceedings, are proportionate to the relief sought. The powers should also be designed to avoid the courts and the judicial system being subjected to undue burdens, to the detriment of the general body of litigants.

This proposal implies that the traditional role of the judge in adversary litigation will require further modification. Effective control over the use of expert evidence in large-scale litigation is likely to involve the managing judge expressing views about the apparent strength, cogency or utility of the evidence a party proposes to adduce. A decision not to permit a party to pursue its preferred course in the litigation may have, or be said to have, important consequences for the presentation of that party’s case. Greater leeway may have to be granted to the judge to allow him or her to exercise the court’s powers without transgressing the borders of permissible pre-judgment of the merits of a case. Appellate courts will need to be supportive of the procedural decisions taken by trial judges in relation to expert evidence if the reforms are to be effective in limiting the burdens placed on the court system by large-scale litigation.

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Case management is now accepted as an integral element in the conduct of civil litigation. The implementation of managerial justice has brought about fundamental changes in the respective roles of judges and the parties’ legal representatives. One of the forces driving these changes has been legitimate concern at the costs, delays and injustices associated with the use of expert evidence in a largely uncontrolled adversary system.

More than a century ago, Learned Hand identified the problem. What has changed is that the courts have demonstrated a willingness and ability to address the problem. The solutions embodied in practice directions, rules of court and judicial decisions interpreting the new regime are not necessarily ideal. Systematic evaluation is required before a definitive judgment can be made about the merits of stringent constraints on the use of expert evidence. But it is tolerably clear that the ancien régime if not dead is terminally ill, and its courtiers must adjust.

The Honourable Justice Ronald Sackville AO

Footnotes

- Australian Law Reform Commission, Managing Justice: A Review of the Federal Civil Justice System (ALRC 89, 2000).

- See, for example, Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW), ss 56, 57.

- Lord Woolf, Access to Justice: Final Report to the Lord Chancellor on the Civil Justice System in England and Wales (1996) (“Woolf Report”), 2.

- (1703) 6 Mod 29; 87 ER 793.

- Id, 30; 794.

- Although the position was soon changed by statute: id, 30, note (d); 794.

- L Hand, “Historical and Practical Considerations Regarding Expert Testimony” (1901) 15 Harv L Rev 40. At the time he wrote this article, Hand was a young lawyer practising in Albany, New York.

- T Golan, Laws of Men and Laws of Nature: The History of Scientific Expert Testimony in England and America (Harvard University Press, 2004), 19.

- Lewis v Rucker (1761) 2 Burr 1167, 1168; 97 ER 769, 770, cited by the NSW Law Reform Commission, Expert Witnesses (Report 109, 2005), par 2.5.

- Id, pars 2.10-2.16.

- Id, par 2.17.

- T Golan, note 8 above, 21-22.

- The first text to discuss expert evidence was the fourth edition of Gilbert’s Law of Evidence, published in 1795: id, 53.

- See, for example, Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), s 79.

- L Hand, note 7 above, 40.

- Id, 50.

- Hand was concerned with a system in which juries determine facts, even in civil cases. Juries in civil cases are now very much the exception in Australia.

- L Hand, note 7 above, 53.

- See, for example, Woolf Report, ch 13; I Freckelton, P Reddy and H Selby, Australian Judicial Perspectives on Expert Evidence: An Empirical Study (AIJA, 1999); H D Sperling, “Expert Evidence: The Problem of Bias and Other Things” (2000) 4 TJR 429. P McClellan, “Expert Evidence: Ace Up Your Sleeve?” (2007) 8 TJR 215, 216-221.

- The New South Wales Law Reform Commission has distinguished between “deliberate partisanship”, “unconscious partisanship” and “selection bias” (choosing experts known to favour the client’s case): NSW Law Reform Commission, note 9 above, pars 5.7—5.13; Victorian Law Reform Commission, Civil Justice Review (Report 14, 2008), 483-487.

- H D Sperling, note 19 above, 430.

- Id, 432.

- Mrs Justice Heather Hallett, “Expert Witnesses in the Courts of England and Wales” (2005) 79 ALJ 288, 288-291.

- Woolf Report, note 3 above, 137.

- Id, 139.

- For a brief survey, see NSW Law Reform Commission, note 9 above, pars 4.2-4.26

- CPR, r 35.3. The Practice Direction to CPR, Part 35, expands on the duties of the expert.

- CPR, r 35.4.

- CPR, r 35.5. Subject to restrictions, a party may put written questions to an expert instructed by another party: r 35.6.

- CPR, r 35.14.

- CPR, r 35.7.

- CPR, rr 35.4, 35.7.

- CPR, r 35.12.

- Code of Guidance on Expert Evidence (2001), par 35.

- For a comprehensive overview of the post-Woolf single expert witness era, see S Burn and B Thompson, “Single Joint Expert” in L Blom-Cooper (ed), Experts in the Civil Courts (Expert Witness Institute, 2006) Ch 5.

- Daniels v Walker [2000] 1 WLR 1382 (CA), 1387, per Lord Woolf MR.

- Id, 1388. As to the significance to be attached to the report of a jointly instructed expert in the face of lay evidence to the contrary, see Armstrong v First York Ltd [2005] 1 WLR 271 (CA).

- Peet v Mid-Kent Health Care Trust [2002] 1 WLR 210 (CA), 215 [21], per Lord Woolf CJ.

- Ibid.

- The research is cited in S Burn and B Thompson, note 35 above, 57.

- G L Davies, “Court Appointed Experts” (2005) 5 QUTLJJ 89, 93-97.

- I do not deal here with the legal principles governing the admissibility of expert opinion evidence, a topic exhaustively treated in texts and commentaries.

- Australian Law Reform Commission, note 1 above, par 6.116.

- P McClellan, note 19 above, 222-224; “Concurrent Expert Evidence” (Keynote address, Medicine and Law Conference, Law Institute of Victoria, 29 November 2007) available at www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/supreme_court/ll_sc.nsf/pages/sco_speeches.

- P McClellan, note 19 above, 223. The NSW Law Reform Commission reported that the concurrent evidence procedure met with overwhelming support from experts and professional organisations: NSW Law Reform Commission, note 9 above, par 6.51.

- FCR, O 34A r 3(2).

- Issued on 5 May 2008.

- Practice Note No 128 (2004) 62 NSWLR 461.

- FCR, O 34.

- FCR, O 10 r 1(2)(d).

- FCR, O 34A r 3(2).

- FLR r 15.51.

- FLR, r 15.42.

- Uniform Civil Procedure Amendment Rule (No 1) 2004 (Qld).

- Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld) (“UCPR(Q)”), r 423.

- UCPR(Q), r 426. One commentator, perhaps unkindly, characterises the provision as merely a “pious hope”: Davies, note 41 above, 99.

- UCPR(Q), r 429R.

- UCPR(Q), r 429S.

- UCPR(Q), rr 429R(6), 429S (11).

- G L Davies, note 41 above.

- UCPR(Q), rr 429H(6), 429N(2).

- UCPR(Q),r 429G(3).

- Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW) (“UCPR (NSW)”) r 31.17. The UCPR (NSW) incorporate recommendations made by the NSW Law Reform Commission.

- The history of the consideration given to the NSW Law Reform Commission’s recommendations, including rejection of the recommendation for a “permission rule”, is traced in Victorian Law Reform Commission, note 20 above, 488-494; cf NSW Law Reform Commission, note 9 above, pars 6.7 — 6.11.

- UCPR (NSW), r 31.19(3).

- UCPR (NSW), rr 31.20, 31.35.

- Stolfa v Owners Strata Plan 4366 (No 2) [2008] NSWSC 531. Cf Tomko v Tomko [2007] NSWSC 1486, where Brereton J granted leave to adduce expert evidence from a psychologist whose opinions differed from those of the jointly appointed expert.

- The Administrative Appeals Tribunal has undertaken “An Evaluation of the Use of Concurrent Evidence in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal” (November 2005). The evaluation was based largely on a survey of members of the Tribunal and found a high degree of satisfaction among members with the use of concurrent evidence. See, too, I Freckelton, P Reddy and H Selby, note 19 above.

- Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2007] FCA 1062 (“C7 Case”), [1].

- R Sackville, “Mega-Litigation: Towards a New Approach” (2008) 27 Civil Justice Quarterly 244, 245ff.

- See Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, 241-242 [322]-[326].

- See, for example, Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (No 14) [2006] FCA 500; Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (No 15) [2006] FCA 515.

- C7 Case, [22]-[23], [1758]-[1759].

- Harrington-Smith v Western Australia (No 7) [2003] FCA 893. In Jango v Northern Territory (No 2) [2004] FCA 1004, the respondents made at least 1100 separate objections to two anthropological reports.

- R Sackville, note 70 above, 251-252.

Case management of civil litigation is now entrenched practice in Australian courts. The rationale underlying case management is that the community has a vital interest in ensuring that litigation is conducted as expeditiously and economically as is consistent with reasonable procedural fairness. A corollary is that if the conduct of litigation is left entirely or largely in the hands of the parties, the consequences will include extensive delays, undue expense and the waste of public and private resources. Accordingly, case management principles entrust primary responsibility to the courts, as distinct from the parties, for minimising delays in finalising litigation, encouraging the parties to explore negotiated or mediated settlement of disputes and ensuring that the costs incurred by the parties are proportionate to the issues at stake. It is no accident that the concept of “managerial justice”1 has now secured not only judicial but legislative endorsement.2

Case management of civil litigation is now entrenched practice in Australian courts. The rationale underlying case management is that the community has a vital interest in ensuring that litigation is conducted as expeditiously and economically as is consistent with reasonable procedural fairness. A corollary is that if the conduct of litigation is left entirely or largely in the hands of the parties, the consequences will include extensive delays, undue expense and the waste of public and private resources. Accordingly, case management principles entrust primary responsibility to the courts, as distinct from the parties, for minimising delays in finalising litigation, encouraging the parties to explore negotiated or mediated settlement of disputes and ensuring that the costs incurred by the parties are proportionate to the issues at stake. It is no accident that the concept of “managerial justice”1 has now secured not only judicial but legislative endorsement.2 The point is illustrated by Buller v Crips,4 a case decided by the Court of King’s Bench in 1703. The Court, presided over by Chief Justice Holt, was confronted with a nice question concerning the status of a promissory note. A purchaser of wine promised to pay the vendor:

The point is illustrated by Buller v Crips,4 a case decided by the Court of King’s Bench in 1703. The Court, presided over by Chief Justice Holt, was confronted with a nice question concerning the status of a promissory note. A purchaser of wine promised to pay the vendor: Two centuries later, one of the great American jurists, Judge Learned Hand, wrote a seminal article pointing out that, before the modern trial by jury emerged, courts or other decision-makers obtained the benefit of expert knowledge primarily in two ways.7 The first was to empanel a special jury of persons especially fitted to judge the facts. This procedure grew out of the medieval community-based jury, whose members were chosen because of their knowledge of the facts of the case and was well established by the fourteenth century, particularly in trade disputes.8 Lord Mansfield, a proponent of merchant juries in commercial cases, justified the procedure in a case decided in 1761:9

Two centuries later, one of the great American jurists, Judge Learned Hand, wrote a seminal article pointing out that, before the modern trial by jury emerged, courts or other decision-makers obtained the benefit of expert knowledge primarily in two ways.7 The first was to empanel a special jury of persons especially fitted to judge the facts. This procedure grew out of the medieval community-based jury, whose members were chosen because of their knowledge of the facts of the case and was well established by the fourteenth century, particularly in trade disputes.8 Lord Mansfield, a proponent of merchant juries in commercial cases, justified the procedure in a case decided in 1761:9

Informal Innovations

Informal Innovations  THE IMPACT OF REFORMS

THE IMPACT OF REFORMS CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION