FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 43 Articles, Issue 43: Aug 2010

“Read the fine print” is on one view, a tired cliché; however, it was potently illustrated as a timeless truism in a recent decision of our Supreme Court.

The facts in Samways v. Workcover Queensland & Ors1

Deluca Properties Pty Ltd (“Deluca”) is a successful building contractor in the Brisbane area. In December 2005, it was engaged as principal contractor in a construction at Darra. It needed a bobcat and operator to prepare part of the site ready for a concrete slab to be poured. It went to Aussie Excavators Plant Hire, a Hiring Agency. There it entered into a “Wet Hire” Contract with Lynsha Pty Ltd. Lynsha, the contractor, provided a bobcat and operator at the site in exchange for the payment of an hourly rate. I will return to the details of that contract shortly.

The Plaintiff, Scott Samways, was employed by Tessman Concreting as a concreter. Tessman Concreting had been engaged by Deluca to lay the concrete slab. By the time of the trial, Tessman had gone into liquidation and its insurer, WorkCover Queensland, had taken over carriage of the action. The afternoon prior to the Plaintiff’s injury, the bobcat, the subject of the hire, had broken down a short distance from where the slab was to be laid. The bobcat’s bucket was raised by its operator, Mr Manning, an employee of Lynsha. He removed the hydraulic hose which had failed, from the bobcat, and left the bobcat parked with its bucket raised to a eight of about 1.5m. He decided to take the failed hose to Pertek which supplied such hoses and had premises nearby, rather than wait for Pertek’s mobile repair service, which may have taken an hour or two to arrive. Manning obtained the replacement hose, but did not return to the site later that afternoon to install it. He thought that the site would be shutting soon after he had left. He returned early the next morning at about 6:00 or 6:30am. He replaced the hose on the bobcat and then returned to work on an excavator. After replacing the hose on the bobcat, Manning neither lowered its bucket nor returned the bobcat to its usual parking position close to the front fence of the construction site.

The Plaintiff and the Tessman team arrived at about 6:30am by which time the hydraulic hose had already been replaced. The foreman of the Tessman team noticed the bucket in its raised position and was concerned about it. He spoke to the site supervisor of Deluca about it. The supervisor responded that he could not move the bobcat because he did not have its key. At about 7:00am whilst the Plaintiff was searching the ground area for a piece of conduit he walked into the raised bucket and injured his shoulder.

The Plaintiff commenced proceedings about his employer, Deluca and Lynsha. All three Defendants denied liability, claimed contributory negligence and issued Contribution Notices against each other.

His Honour Justice Appplegarth found all three Defendants liable. He found that Lynsha was liable for negligence of Manning in failing to move the bobcat or lower its bucket once he had repaired it on the morning of 6 December. He found that the site supervisor, employed by Deluca, was similarly negligent for failing to move the bobcat or make arrangements to have it moved. He found Tessman liable in that it failed to direct its employees not to carry out tasks in the rea and by failing to barricade the area surrounding the bobcat. in terms of the apportionment between Defendants, His Honour found 60% of the liability against Lynsha, 30% against Deluca and 10% against Tessman. He also reduced the Plaintiff’s damages by 20% on account of contributory negligence.

His Honour Justice Appplegarth found all three Defendants liable. He found that Lynsha was liable for negligence of Manning in failing to move the bobcat or lower its bucket once he had repaired it on the morning of 6 December. He found that the site supervisor, employed by Deluca, was similarly negligent for failing to move the bobcat or make arrangements to have it moved. He found Tessman liable in that it failed to direct its employees not to carry out tasks in the rea and by failing to barricade the area surrounding the bobcat. in terms of the apportionment between Defendants, His Honour found 60% of the liability against Lynsha, 30% against Deluca and 10% against Tessman. He also reduced the Plaintiff’s damages by 20% on account of contributory negligence.

The indemnity clause

Lynsha sought a full indemnity from Deluca because of the terms of the written contract of hire in relation to the bobcat. The contract described Deluca as the hirer and Lynsha as the contractor. The pivotal clause relied on was worded as follows:

“HIRER’S RESPONSIBILITY FOR LOSS AND DAMAGE

7. The hirer shall fully and completely indemnify the contractor in respect of all claims by any person or party whatsoever for injury to any person or persons and/or property caused by or in connection with or arising out of the use of the plant and in respect of all costs and charges in connection therewith whether arising under statute or common law.”

Justice Applegarth also considered clause 5 was relevant when it came to the construction of the contract:

“HANDLING OF PLANT

5. When the driver or operator is supplied by the contractor to work the plant he should be under the control of the hirer. Such drivers or operators shall for all purposes in connection with their employment of the working of the plant be regarded as the servants or agents of the hirer who alone shall be responsible for all claims arising in connection with the operation of the plant by the said drivers or operators. The hirer shall not allow any other person to operate such plant without the contractor’s consent to be confirmed in writing.”

It was argued on behalf of Deluca that the clause did not protect Lynsha against the consequences of its own negligence. Further, it was argued on behalf of Deluca that the Plaintiff’s injury was not caused by/in connection with, or arise out of the “use” of the plant. The bobcat had not been used for at least 14 hours, was unoccupied and was rendered useless by reason of its breakdown and in those circumstances, it was argued that it could not be concluded that the injury had any connection with the “use” of the bobcat.

Justice Applegarth recognised that an indemnity clause must be construed strictly and that any doubt as to its construction should be resolved in favour of the indemnifier.

His Honour held that the clause should be construed in its contractual context which allocates risks of different kinds between the parties and, relevantly in this case, provided that the operator shall be under the control of the hirer. He stated that the fact that the contract requires a party to take out insurance against the indemnified liability may be taken into account in concluding that the indemnity applies to that liability, whether or not insurance is in fact taken out. The absence of a provision for insurance against the liability may also be taken into account. However, the fact that the indemnifier is not required by the contract to take out insurance, and chooses not to take out insurance, should not affect the construction of indemnity that unambiguously allocates responsibility for the liability against the indemnifier.

His Honour held that the clause should be construed in its contractual context which allocates risks of different kinds between the parties and, relevantly in this case, provided that the operator shall be under the control of the hirer. He stated that the fact that the contract requires a party to take out insurance against the indemnified liability may be taken into account in concluding that the indemnity applies to that liability, whether or not insurance is in fact taken out. The absence of a provision for insurance against the liability may also be taken into account. However, the fact that the indemnifier is not required by the contract to take out insurance, and chooses not to take out insurance, should not affect the construction of indemnity that unambiguously allocates responsibility for the liability against the indemnifier.

His Honour noted the line of authority which construes contracts of the present kind and the assumption that it is inherently improbable that a party would contract to absolve the other party against claims based on the other party’s own negligence.2 He noted also the competing view that at least the principal purpose for obtaining such an indemnity is to protect a party against liability for its own fault.3

His Honour noted that the expressions “arising out of” and “in connection with” are capable of having wide meanings. In the end result, he found that in the present context, there must be a sufficient nexus between the use of the plant and the injury. He stated:

“The apparent breadth of cl 7 in extending the indemnity to claims for personal injuries ‘caused by or in connection with or arising out of the use of the plant’, including claims in respect of Lynsha’s own negligence, arises from the ordinary language of the clause. The commercial and contractual context in which cl 7 applies does not make it improbable that Lynsha would seek to be indemnified against claims for damages caused by its own negligence. The plant was under the control of Deluca. Lynsha might be found liable to a third party by reason of the negligence of its employee, as occurred in this case. However, as between Lynsha and Deluca, the employee was under the control of Deluca. In circumstances in which Lynsha ceded control over the operator and Deluca assumed that control, the clause should be construed according to its ordinary meaning to extend the claims for liability for personal injury in circumstances in which Lynsha is vicariously liable for the negligence of its employee.’4

Thus, it can be seen that His Honour considered the inclusion of clause 5 (earlier referred to) as being very important.

His Honour then considered the meaning of the word “use” in the present context. He referred to various dictionary definitions which include:

“the act of employing a thing for any … purpose, application or conversion to some … end;

to employ for some purpose; put into service;

to avail oneself of; apply to one’s own purposes;

the state of being employed or used.”

Justice Applegarth held that in its context in the contract, the word “use” should not be interpreted as being restricted to the “operation” of the plant. The word “operation” is used in clause 5 and if the indemnity was intended to apply to the operation of the plant, as distinct from its use, then the word “operation” presumably would have been used in clause 7. The word “use” is not confined to circumstances in which the plant is being “driven” or “operated” (terms used in clause 13). It is wide enough in His Honour’s view to include circumstances in which the plant is being employed or utilised for some purpose or end.

To support his conclusion, His Honour referred to Dickinson v. Motor Vehicle Insurance Trust5 a case in which a father left his two children in a parked car as he went shopping. Whilst inside, one of the children found some matches and started a fire. The other child sued her father for damages and the Motor Vehicle Insurance Trust for a declaration that it was liable to pay the amount of any judgment against the father. The High Court held that the injuries had arisen out of the use of a vehicle within the meaning of that term as used in the relevant legislation. The vehicle was in use to carry the children as passengers in the course of a journey which was interrupted to enable the father to do some shopping. There was no suggestion that the interruption was other than temporary. The word “use” for the purposes of the Act extend to everything that fairly fell within the conception of the use of a motor vehicle and may include a use which does not involve locomotion.

Justice Applegarth thus resolved the issue in favour of Lynsha, concluding that the Plaintiff’s personal injury was in connection with or arising out of the use of the bobcat. The bobcat was in use at the relevant time. The breakdown had been repaired. The operator, who was under Deluca’s control, repaired it and left it in its location, rather than move it. The word “use” in clause 7 was not ambiguous and could not be construed to mean that the plant was being driven or operated. At the time of the accident, the plant was in use, being in an operational condition and having been parked with a view to being deployed on tasks at the direction of Deluca. The deployment of the plant at that location involved its use for the purpose of the hire. There was a sufficient nexus between the Plaintiff’s personal injury and the use of the plant to conclude that his personal injury was in connection with or arose out of the use of the plant. Lynsha was thereby entitled to an indemnity against the Plaintiff’s claim and in respect of costs.6

Thus, the fine print on the back of a Bobcat Hire Agreement was sufficient to protect Lynsha in circumstances where the primary finding was that its operator had been the primary tort feasor in the action.

The decision has been met with some consternation by insurance lawyers, not because it is perceived as being incorrect, but because indemnity clauses have not enjoyed a successful run in our courts and this case represents a significant shift. A look at the Form Guide would have had most punters putting their money on Deluca in this contest.

Westina Corporation Pty Ltd v. BGC Contracting Pty Ltd7

Westina Corporation Pty Ltd v. BGC Contracting Pty Ltd7

An appeal by the indemnifying party (Westina) to the Western Australia Court of Appeal was successful. A brief summary of the facts are these:

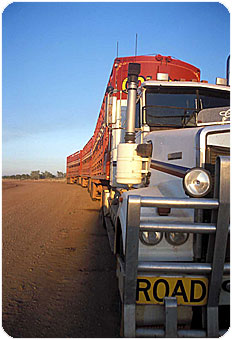

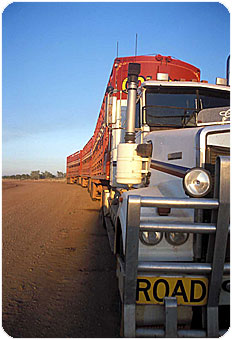

Westina Corporation was a haulage contractor. In 2005 it hired a road-train comprising a prime mover and three trailers to BGC, pursuant to the terms of a written “Wet Hire” Agreement. The Wet Hire Agreement obliged Westina to provide the services of a qualified operator for the road-train. The Hire Agreement contained the following terms:

- a warranty by Westina that the hired equipment was “in sound mechanical condition” and an agreement to “defend, indemnify and hold BGC harmless against any injury, death, claim or other such loss arising out of the use of the plant by BGC except to the extent caused by BGC’s willful misconduct’;

- a risk allocation and indemnity clause:

“the supplier (Westina) shall bear the risk of loss in hiring of the plant and must defend, indemnify and hold BGC harmless against any injury, death, claim or other loss arising from the hiring of the plant.”

- a clause requiring Westina to effect Public Liability Insurance and Workers’ Compensation Insurance.

The hired road-train was involved in a collision with an oncoming road-train in June 2005. The Westina prime mover was being driven by an employee of Westina who was killed in the collision. The road-train with which he collided was co-incidentally owned by BGC and driven by one of its (BGC’s) employees. The trial judge concluded that the accident occurred as a result of the negligence of the BGC employee and that BGC was vicariously liable for that negligence.

BGC sought to rely on indemnities in the Wet Hire Agreement and to argue that they operated in respect of any loss arising from the hiring of the plant, even in circumstances where the cause of the loss was the negligence of the BGC employee. The trial judge upheld this contention and found that the risk allocation and indemnity clause, on its clear terms, was wide enough to cover any loss or damages arising out of the hiring. In the trial judge’s view, it was not “appropriate to try and establish ambiguity where non exists”.

The Western Australia Court of Appeal was unanimous8 in upholding Westina’s appeal. After referring to the relevant authorities, the Court held that in the circumstances, the indemnity clause was inconsistent with the insurance arrangements provided for in the Hire Agreement. In particular, it was concluded that there was no insurance policy (which was compulsory under the agreement) which was available to indemnify Westina in respect of the loss of the prime mover and three trailers where that loss was caused by the negligence of BGC or its employee in the operation of other plant and equipment (relevantly, the BGC truck).9

It was held that the indemnity and the risk that Westina must bear in relation to the truck and trailers, did not extend to the risk of loss caused by the negligent operation by BGC or its employee of other plant and equipment.10 The Court determined that there was doubt or uncertainty arising from the apparent breadth of possible application of the indemnity which must be resolved in favour of Westina as the indemnifier.11

Erect Safe Scaffolding (Australia) Pty Limited v. Sutton12

Erect Safe Scaffolding (Australia) Pty Limited v. Sutton12

The facts in that case were these:

A worker employed by a formwork company, was injured when his head struck one of the cross-bar ties which extended across a walkway on a scaffold put up by a scaffolding company. He claimed damages against his employer, the principal contractor (Australand) and the scaffolding company which erected the scaffold (Erect Safe). The trial judge found that the principal contractor and Erect Safe had been negligent. He also found that Erect Safe was bound to indemnify Australand, pursuant to the clauses in the sub-contract between them. The indemnity clause was in the following terms (clause 11):

“The sub-contractor must indemnify Australand against all damages, expense (including lawyers fees and expenses on a solicitor/client basis), loss (including financial loss) or liability of any nature suffered or incurred by Australand arising out of the performance of the sub-contract works and its other obligations under the sub-contract.”

The sub-contract contained the following insurance clause (clause 12):

“The sub-contractor must effect and maintain during the currency of the sub-contract, Public Liability Insurance in the joint names of Australand and the sub-contractor to cover them for their respective rights and interests against liability of third parties for loss or damage to property.”

Erect Safe failed to maintain such insurance in accordance with the policy.

In allowing the appeal by Erect Safe13 it was held that an indemnity clause in a sub-contract by which a sub-contractor agreed to indemnify the head-contractor against all damage that the head-contractor suffered “arising out of performance of the sub-contract works and its other obligations under the sub-contract”, only imposes a liability on the sub-contract for damage occasioned by any act or omission which it committed. Accordingly, where damage was caused, in part, by the negligence of a sub-contractor bound by such an indemnity clause, but was also caused, in part, by an independent act of negligence by its head-contractor, the latter’s liability was as a result of its own negligent act, rather than arising out of the performance of the sub-contract works by the sub-contractor, and the indemnity clause was not engaged.

As McClellan CJ expressed it:

“The question in the present dispute is whether cl 11 confines the liability of Erect Safe to indemnify Australand for liabilities arising from Erect Safe’s performance in the sub-contract works or whether it extends to a liability of Australand which arises in relation to those works. To my mind the indemnity is confined. Although the appropriate meaning may have been more obvious if the word ‘its’ had been included before the words ‘performance of the sub-contract works’, I do not believe the clause lacks clarity. However, if the clause is ambiguous, it would have to be construed in favour of the surety, Erect Safe …

Clause 11 provides for Erect Safe to indemnify Australand against all ‘damage etc’. Although the indemnity is initially described in broad terms, it is confined by the word ‘arising’. The clause provides that the relevant obligation can arise in two situations being:

‘out of the performance of the sub-contract works’ and ‘its (Erect Safe’s) other obligations under the subcontract.’

In the present case the liability of Australand does not ‘arise’ out of the performance by Erect Safe of any of its contractual obligations. Although it is true that the occasion for the liability of Australand was the erection by Erect Safe of the faulty scaffolds, the liability of Australand arises from its own independent act of negligence in failing to maintain the appropriate safety regime for the site.”

Justice McClellan considered that clause 12 (the insurance clause) followed clause 11 and that Erect Safe was not required to insure the liabilities of Australand arising from the negligence of Australand.

Of interest in the decision is the strong dissent of Justice Basten. He refers to the High Court decision in Davis v. Commissioner for Main Roads.14 In that case the court held that an indemnity protected the Commissioner, notwithstanding that the accident had been due to the separate negligent conduct of the respondent. The indemnity clause read as follows:

“The contractor shall undertake the whole risk of carrying out the contract, and without limiting the generality thereof, shall:

(a) hold the Commissioner indemnified against all claims arising out of:

(i) damage to the property of the contractor or any third party;

…

whether such damage … is caused by the use of a motor vehicle or by goods falling or projecting therefrom or otherwise howsoever …”

Justice Basten points out that it is the minority judgment in that case which is often referred to in later judgments.15 That argument (asserted by the minority) fails to explain, according to Justice Basten, how and in what circumstances a head-contractor could be liable vicariously for the negligence of a sub-contractor so as to make out a plausible purpose for an indemnity, so limited. His Honour considered the reasoning of Justice Menzies more compelling, namely that the only practical purpose for taking such an indemnity would be to protect the Commissioner against liability for its own fault. Once it appears the indemnity does extend to the Commissioner’s fault, including negligence, there is no sound reason for limiting the indemnity to particular breaches of a duty of care.16

His Honour also referred to Leighton Contractors Pty Ltd v. Smith17 where the New South Wales Court of Appeal considered the following indemnity clause:

“The sub-contractor … shall indemnify and keep indemnified the company … against all loss and damage including but not limited to all physical loss or damage to property (other than property for which the sub-contractor is responsible under clause 16) and all loss or damage resulting from death or personal injury arising out of or resulting from any act, error, or omission or neglect of the sub-contractor.”

His Honour pointed out that in circumstances where both Leighton and the sub-contractor were found liable to the worker; the court unanimously held that the natural and ordinary meaning of the indemnity clause required the sub-contractor to indemnify Leighton Contractors for its liability.

His Honour pointed out that the decision in Leighton was not referred to in the subsequent New South Wales Court of Appeal decision of Roads and Traffic Authority of New South Wales v. Palmer18 and was distinguished by the Court in F & D Normoyle Pty Ltd v. Transfield Pty Ltd.19

In the end result, Justice Basten adopted the approach used in Davis and Leighton Contractors in holding that the implied limitation that required the liability of the contractor to be entirely derivative from that of the sub-contractor, would derive the indemnity of any operation and should be rejected.

Ellington v. Heinrich Constructions Pty Ltd & Ors20

The Queensland Court of Appeal earlier considered the operation of an indemnity clause in Ellington. The Court of Appeal held that the indemnity did not operate to protect the builder in this instance. The clause provided:

“The sub-contractor shall not commit any act of trespass or commit any nuisance or be guilty of any negligence and shall effectually protect and hereby indemnifies the builder and the builder’s employees against all loss, damage, injury or liability whatsoever that may occur in respect of the works or through the execution of the works and in case of any such loss, damage, injury or liability occurring, the sub-contractor shall make full compensation, shall make good all such loss, damage, injury or liability and if the builder is required to pay any damages for such loss, damage, injury or liability, the amount of such damages made together with all costs which the builder may have incurred in defending or settling the claim for such damages, may be deducted from any monies due or becoming due to the sub-contractor under this contract or may be recovered from the sub-contractor as liquidated damages…”

On appeal, the clause was in very similar terms to the clause in Canberra Formwork Pty Ltd v. Civil & Civic Ltd & Anor21. The clause in that case was held to be unsuccessful in indemnifying a party against the consequences of its own negligence. It was also held to be ambiguous. The trial judge in Ellington noted that the appellant and respondent agreed to the inclusion of the clause (well after) the decision in Canberra Formwork which had determined the proper construction of a relevantly identical clause. His Honour supposed the parties intended the clause to have the meaning ascribed to it by the court in that case. The Court of Appeal considered this to be an imminently sensible approach.

The argument that the obligation would be backed by insurance policies which were required to be taken out was not accepted as the policy fell short of covering all of the liability which the respondent would impose upon the appellant pursuant to the indemnity. The decision of the trial judge in holding that the indemnity did not apply was upheld.

Of interest is that the judgment of Blackburn CJ quoted with approval by our Court of Appeal in Canberra Formwork, is one that adopts the dissenting reasoning of Kitto J in Davis. Further, the Court does not refer to the majority view in Davis, or the decision of the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Leighton.

Discussion

It is not easy, in fact some would suggest impossible22 to reconcile all of the above decisions. By and large, they turn on their own facts and the idiosyncrasies of the particular clause relied upon. However, if the clause is unambiguous, there is no good reason to suppose that the approach taken by Applegarth J in Samways is not a portent of a broader approach to be taken by the courts. Justice Applegarth’s decision echoes the sentiments of Basten JA in Erect Safe which in essence, resurrects the majority High Court decision in Davis and the unanimous decision of the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Leighton Contractors. In an era where greater commercial sophistication is assumed, together with the almost universal role of insurance companies, I would not be surprised if the courts began adopting a far more literal approach to the interpretation of indemnity clauses, rather than the hitherto experience of looking for, and finding an ambiguity.

The possible ramifications

In personal injury litigation, indemnity clauses, which hitherto have been paid dubious respect, may now become paramount in the minds of parties responding to the claim of an injured Plaintiff. The previous attitude was borne out of pragmatism having regard to the lack of success enjoyed by those seeking to enforce such clauses. The Samways decision shows that provided the clause is unambiguous and consistent with the contract as a whole, there is no good reason why it will not be enforced.

It in my view is flawed logic to suppose that a commercial entity would not contract to secure an indemnity against its own negligence. Otherwise, the clause provides no more protection than that provided by the joint tortfeasors’ legislation23. As stated earlier, the reasoning of Basten JA is compelling and may represent the way forward for our courts.

It is becoming increasingly common in labour hire agreements for there to be an indemnity in favour of the host employer against the labour hire company This is exceedingly important from an insurance point of view, because the labour hire company’s Workcover policy will not respond to such a claim. Thus, the extent of the public liability insurance becomes of pivotal and practical signifance when considering settlement negotiations, particularly for co-defendants in an action or co-respondents to a claim.

RJ Lynch

07 July 2010

Footnotes

- [2010] QSC 127

- Davis v. Commissioner for Main Roads (1968) 117 CLR 529 at 534, per Kitto J (Windeyer J agreeing); Westina Corporation Pty Ltd v. BGC Contracting Pty Ltd [2009] WASCA 213 at [64] – [65]

- Davis v. Commissioner for Main Roads, supra, at 537 per Menzies J (Barwick CJ and McTiernan J agreeing; Erect Safe Scaffolding (Australia) Pty Ltd v. Sutton (2008) 72 NSWLR 1 (per Basten JA)

- At para [74] of the judgment

- (1987) 163 CLR 500

- See para [78] – [80] of the judgment

- [2009] WASCA 213

- Wheeler JA and Newnes JA concurring with the reasons expressed in the judgment of Buss JA

- Supra, para [75]

- At para [78]

- Para [83]

- [2008] 72 NSWLR 1

- Giles JA, McClellan CJ at CL, Basten JA dissenting

- (1967) 117 CLR 529

- Kitto J with whom Windeyer J agreed

- At 537 of Davis and discussed at paragraphs [56] – [59] of Basten JA’s judgment in Erect Safe

- [2000] NSWCA 55

- (2003) 38 MVR 82

- (2005) 63 NSWLR 502

- (2004) QCA 475

- (1982) 41 ACTR 1

- See the judgment of Basten JA in Erect Safe, supra

- See 56 of the Law Reform Act 1995 (Qld)

His Honour Justice Appplegarth found all three Defendants liable. He found that Lynsha was liable for negligence of Manning in failing to move the bobcat or lower its bucket once he had repaired it on the morning of 6 December. He found that the site supervisor, employed by Deluca, was similarly negligent for failing to move the bobcat or make arrangements to have it moved. He found Tessman liable in that it failed to direct its employees not to carry out tasks in the rea and by failing to barricade the area surrounding the bobcat. in terms of the apportionment between Defendants, His Honour found 60% of the liability against Lynsha, 30% against Deluca and 10% against Tessman. He also reduced the Plaintiff’s damages by 20% on account of contributory negligence.

His Honour Justice Appplegarth found all three Defendants liable. He found that Lynsha was liable for negligence of Manning in failing to move the bobcat or lower its bucket once he had repaired it on the morning of 6 December. He found that the site supervisor, employed by Deluca, was similarly negligent for failing to move the bobcat or make arrangements to have it moved. He found Tessman liable in that it failed to direct its employees not to carry out tasks in the rea and by failing to barricade the area surrounding the bobcat. in terms of the apportionment between Defendants, His Honour found 60% of the liability against Lynsha, 30% against Deluca and 10% against Tessman. He also reduced the Plaintiff’s damages by 20% on account of contributory negligence. His Honour held that the clause should be construed in its contractual context which allocates risks of different kinds between the parties and, relevantly in this case, provided that the operator shall be under the control of the hirer. He stated that the fact that the contract requires a party to take out insurance against the indemnified liability may be taken into account in concluding that the indemnity applies to that liability, whether or not insurance is in fact taken out. The absence of a provision for insurance against the liability may also be taken into account. However, the fact that the indemnifier is not required by the contract to take out insurance, and chooses not to take out insurance, should not affect the construction of indemnity that unambiguously allocates responsibility for the liability against the indemnifier.

His Honour held that the clause should be construed in its contractual context which allocates risks of different kinds between the parties and, relevantly in this case, provided that the operator shall be under the control of the hirer. He stated that the fact that the contract requires a party to take out insurance against the indemnified liability may be taken into account in concluding that the indemnity applies to that liability, whether or not insurance is in fact taken out. The absence of a provision for insurance against the liability may also be taken into account. However, the fact that the indemnifier is not required by the contract to take out insurance, and chooses not to take out insurance, should not affect the construction of indemnity that unambiguously allocates responsibility for the liability against the indemnifier.  Westina Corporation Pty Ltd v. BGC Contracting Pty Ltd7

Westina Corporation Pty Ltd v. BGC Contracting Pty Ltd7 Erect Safe Scaffolding (Australia) Pty Limited v. Sutton12

Erect Safe Scaffolding (Australia) Pty Limited v. Sutton12